What do we know about this problem?

Medical students are not frequently familiar with Anesthesia as a medical specialty. The reason may probably be that the specialty is often overlooked by medical school curricula. When included in the programs, the clerkships and topics addressed are highly heterogeneous, as it is commonly based on shadowing in the surgical environment and lectures. This greatly limits the exposure of medical students to anesthesia, which affects their perception about the specialty, and may result in inadequate training of skills commonly performed by anesthesiologists.

What does this study contribute?

Our proposal is practical and highly valued by both students and professors; furthermore, it may be successfully included in every medical school curriculum, or offered as an elective clerkship for students interested in the specialty. Moreover, notwithstanding the fact that the proposal was developed during the COVID-19 pandemic, fulfilling all of the restrictions imposed by the Colombian government, we did not experience any reported outbreaks. Hence we believe that this proposal may be widely implemented not just as a biosafe alternative, but as a novel curriculum tailored to strengthening a student-centered approach to learning, values, attitudes, and behavior ofanesthesiology.

INTRODUCTION

Medical students are not frequently familiar with Anesthesia as a medical specialty. The reason may probably be that the specialty is often overlooked by medical school curricula. 1 When included in the programs, the clerkships and topics addressed are highly heterogeneous, as it is commonly based on shadowing in the surgical environment and lectures. 2,3 This greatly limits the exposure of medical students to anesthesia, which affects the students' perceptions of the specialty, and may result in inadequate training of skills commonly performed by anesthesiologists.

A standardized approach to the inclusion of an anesthesiology curriculum in medical school can be invaluable for students, their prospective careers, and their clinical practice. Most students become acquainted with the specialty while attending the medical school, and anesthesiology skills are highly desirable for any general practitioner or specialist. Airway management, vascular access, perioperative management, critical care, applied pharmacology and physiology, or answering patients' doubts about common anesthesiology procedures, are all broad skills applicable to any area of medicine. 4,5 This is especially relevant in lower to middle-income countries (LMIC) or underserved areas, where there is frequently limited access to specialist care. 6 Unfortunately, appropriate training in these topics is infrequent; as much as 30% of medical school students felt uncomfortable and ill- prepared to perform invasive procedures such as airway management or securing vascular access. 7

The anesthesiology teaching deficiencies were more pronounced during the COVID-19 pandemic, as the clinical setting and access to procedures were restricted for students. 8,9 There is a need for orienting the anesthesiology clerkship during medical school towards a competency-based approach in a biosafe scenario that still ensures adequate learning of the basic skills and concepts of anesthesia, providing appropriate exposure to the specialty. 3,10

According to the competency-based approach, a simulation-based anesthesiology curriculum was developed compliant with the education and safety standards during the COVID-19 pandemic, since these methodologies could greatly reduce the probability of contagion by microorganisms. 11 Furthermore, this newly developed curriculum could also serve to strengthen the anesthesiology teaching and learning practices during medical school in the post-pandemic era. A pilot program was implemented with fourth-year medical students and trainers at Universidad de los Andes (Bogotá, Colombia), who later were surveyed about their perceptions of the curriculum and its impact on their learning.

METHODS

The curriculum included a mandatory three-week period for fourth-year medical school students of the Universidad de los Andes (Bogotá, Colombia), which was divided into a virtual component (28 hours) and a simulation component (38 hours). The topics evaluated during the pilot program were chosen based on the most common scenarios and challenges general practitioners could face, in accordance with the key capabilities of anesthesia previously defined by Smith et al. 12 The topics included were discussed among the different course coordinators of the various specialties, ensuring consistent and not repetitive curricula across the different clerkships.

Once the main topics were defined for the curriculum, the activities were designed considering the principles of Kolb's experiential learning and Ausubel's meaningful learning. David Kolb described learning as a continuous process based on experiences. He developed a four-phase cycle for learning to occur, starting with living the experience/perception, followed by its analysis and discussion that led to the third stage, in which the individual discovers the learning and finally applies the new knowledge. 13 Along the same line, Ausubel argued that new knowledge could be acquired whenever it was interpreted and related to prior knowledge. Thus, the perfect learning environment was the one in which the student experienced, acted freely, and absorbed information facilitated by the professors. 14 Therefore, the curriculum included relevant and adequate activities within their professional competencies easily transferable to real-life settings (Table 1).

Table 1 Planned daily activities. Each task was designed considering the different Kirkpatrick levels.

* Approximate number of hours required for the student to complete and prepare each activity.

Source: Authors.

The Merrienboer four-phase instructional design model (4D/IC) was used in the development of each workshop with a view to teach complex skills through a competency-based education program in four different steps. The first step called "learning tasks", is intended for students to apply routine and non-routine skills through cases and projects, ideally in an actual work environment, receiving constant guidance from a professor. The second step is "supportive information", where the students link prior knowledge to new knowledge learned to perform a non-routine skill. The third step called procedural information, helps students to automate routine skills. And the last step, commonly referred to as the part-task practice, is important for some information to be fixed; it consists of repetitive practice after the complete learning experience of the non-routine and routine skills. 15

As mentioned in the previous model, expert support and guidance are most important in the first phases and should be tapered as the students master their abilities. 15 Thus, the anesthesiology department professors were educated on the curriculum and goals of the activities. Each anesthesiologist was assigned for one week to the same group to ensure the successful development of the activities, assess the longitudinal performance of the students, and provide adequate feedback upon completion of each activity.

The proposal was implemented from July to December 2020. At the end of the curriculum, a survey designed according to the Kirkpatrick model - which is a 4-level training evaluation model - was administered to students and professors. The first level determines how the participants reacted to each item of the activity (setting, instructor, methodology, cases, etc.); the next level discusses whether the main learning objectives were achieved; the third level determines whether the new knowledge has been applied on the job; finally, the last level is intended to show whether the learning persists over time. 16 However, level four is challenging to evaluate since it involves a longitudinal assessment (Table 2), and hence the perceived impact on knowledge and motivation was used as a surrogate marker. Levels 1, 2, and 4 were assessed with a 5-point Likert scale response, while level 3 was assessed using a yes/ no specific questionnaire. The professors' questionnaire used a 4-level Likert scale. Finally, because of our pilot study design, the survey questions were analyzed using proportions as descriptive statistics for all the Kirkpatrick levels.

RESULTS

A total of 53 students were enrolled during the second half of 2020. From 53 attendees, 44 students answered our survey at the end of the semester (83%). A total of 5 anesthesiologists performed the established curricular activities, and all the anesthesiologists answered the survey at the end of their participation. Notwithstanding the active COVID-19 pandemic during this semester and the occurrence of sporadic positive cases, no cases or outbreaks were linked to our curriculum proposal. The results of the survey are explored according to the Kirkpatrick level evaluated.

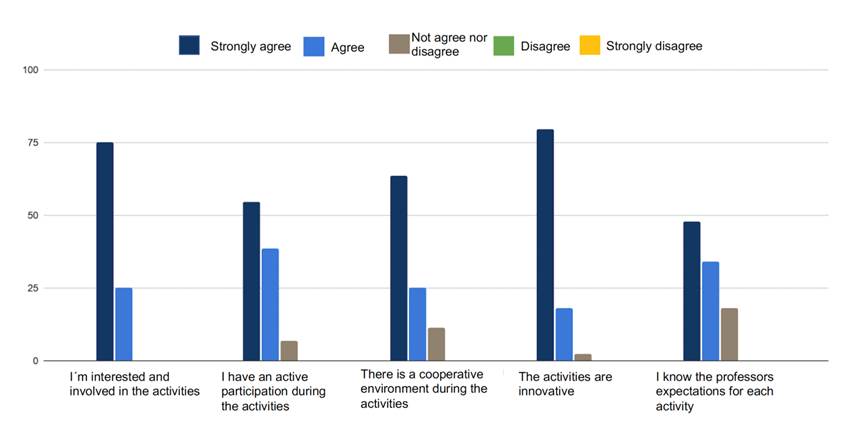

In terms of reaction, most students found the curriculum interesting, highly engaging, encouraging, satisfying, and innovative, with more than 80% strongly agreeing with these characteristics (Figure 1). The professors also agreed with these characteristics. However, although the professors felt that the activities had clear objectives, 1 out of 5 students disagreed with this statement.

Source: Authors.

Figure 1 Performance of the reaction level according to the Kirkpatrick levels of evaluation.

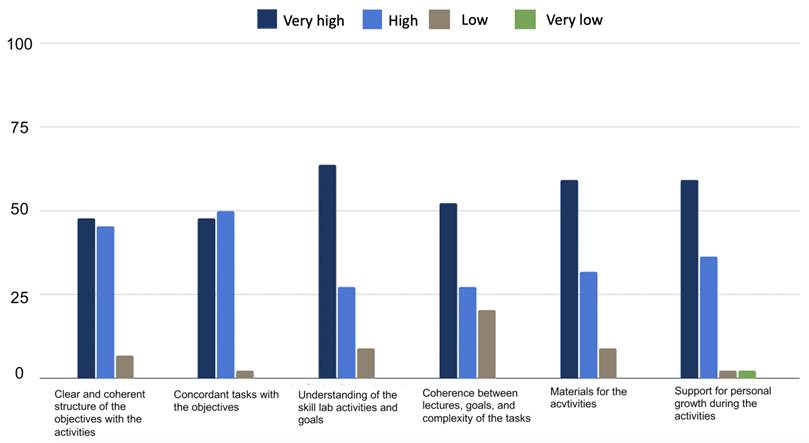

At the learning level, most students (95%) found a high correlation between the learning objectives and the contents of the activities. Fifty-three percent (53%) of the students found a very high consistency between the theory and the complexity of the tasks (Figure 2). A similar situation was evidenced among the professors, who found the activities and skills highly applicable and relevant for a general practitioner.

Source: Authors.

Figure 2 Performance of the learning level according to the Kirkpatrick levels of evaluation.

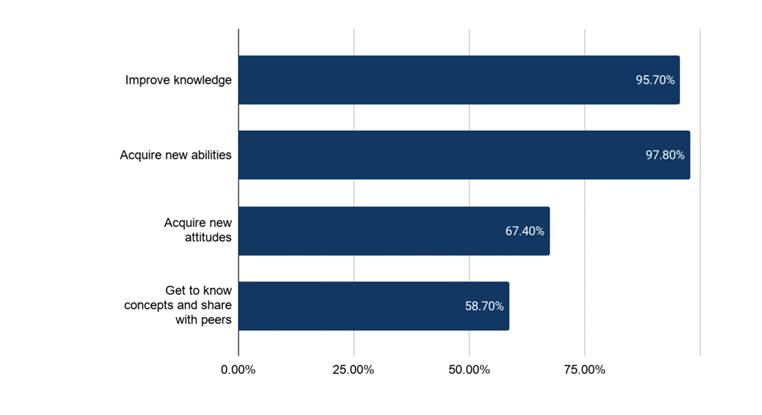

At the behavior level, the activities and simulations helped to improve knowledge (95.7%), to acquire new skills (97.8%) and attitudes (67.4%), and to share such knowledge and skills with peers (58.7%) (Figure 3). All the professors thought the activities were useful for developing competencies for future real-life situations, and effectively prepared the students to successfully perform these activities as general practitioners.

Source: Authors.

Figure 3 Performance of the behavior level according to the Kirkpatrick levels of evaluation.

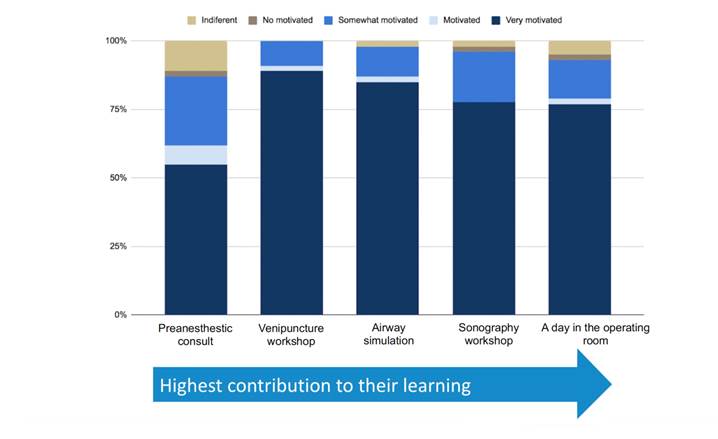

At the results level, the classical assessment of this outcome measures the long-term change in real-life settings for the students. Motivation and long-term relevance from the student's perspective were chosen as a surrogate to indicate the representative outcome for each activity. Interestingly, not all the activities showed consistent results in these two areas (Figure 4). The venipuncture workshop - though it was the least relevant for the students' learning objective - was the most motivating workshop for students. The remaining activities got concordant results at this level. The pre-anesthesia assessment was the least motivating activity with the lowest contribution to learning. Finally, the "day in surgery" simulation and the echography workshop contributed the most to learning, and 76% of the students were highly motivated by these activities (Figure 4). In addition, almost all of the professors (80%) were of the opinion that the students could reproduce their skills in a new environment (Table 3).

Source: Authors.

Figure 4 Performance of the results level according to the Kirkpatrick levels of evaluation.

Table 3 Professor's assessment.

| Kirkpatrick level | Domains | Very high (%) | High (%) | Low/very low (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level 1 Reaction | Topic relevance | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Clarity of the objectives for each activity | 100 | 0 | 0 | |

| Consistency among objective, activity, and skills evaluated* | 80 | 20 | 0 | |

| Level2 Learning | Practicality for the general practitioner | 60 | 40 | 0 |

| Consistency between lectures, texts, and activities | 100 | 0 | 0 | |

| Applicability for the general practitioner | 80 | 20 | 0 | |

| Level 3 Behavioral changes | Ability of the curriculum to develop new skills and knowledge | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Level 4: Changes in professional life | Ability to perform the skills in a new environment | 80 | 20 | 0 |

* This question evaluates level 1 and level 2 concepts.

Source: Authors.

DISCUSSION

Medical education has been changing over the past decades. The focus in medical school curricula is shifting from knowledge-focused programs to appreciating knowledge, values, attitudes, and behavior. 17 Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic imposed restrictions that severely limited learning opportunities and restricted the contact of medical students with patients in the clinical setting. 18 Under these circumstances, simulations offer an excellent opportunity to holistically teach and evaluate medical students. Simulation should be a key component of teaching anesthesia as a transition tool for reducing patient and exposure risks and enhancing theoretical and practical knowledge. 4

Our proposal is practical and highly valued by both students and professors; furthermore, it may be successfully included in every medical school curriculum, or offered as an elective clerkship for students interested in the specialty. Moreover, notwithstanding the fact that the proposal was developed during the COVID-19 pandemic, fulfilling all of the restrictions imposed by the Colombian government, we did not experience any reported outbreaks. Hence we believe that this proposal may be widely implemented not just as a biosafe alternative, but as a novel curriculum tailored to strengthening a student-centered approach to learning, values, attitudes, and behavior of anesthesiology.

Medical students and trainees have experienced the accelerated transition to e-learning because of the COVID-19 pandemic around the world. 19-21 A number of studies have found that interactivity, understanding of the content, convenience, and active participation are associated with increased satisfaction of medical science students with e-learning. 22,23 Our proposed curriculum combines flipped classroom methodology with simulations and workshops, maximizing the efficiency of e-learning, and focusing on developing a strong framework of skills and attitudes which are valuable to the general practitioner. The survey results consistently showed a high satisfaction across the different Kirkpatrick levels from the perspective of both students and professors.

Although no consensus has yet been reached regarding the inclusion of anesthesia as a mandatory clerkship during medical school 4, various skills of the specialty are commonly practiced by many practitioners, such as intubation, pain management, fluid resuscitation, etc. This is particularly relevant in low-to-middle-income countries and in underserved areas of developed countries, since highly specialized procedures and skills, such as intubation, pain management, fluid resuscitation, etc. are often performed in these settings where specialists are not easily available. 24-26 The adoption of an anesthesia curriculum based on our validated proposal could strengthen these skills among the future general practitioners, and benefit medical professionals and patients.

Our results are promising, though important limitations should be considered. First, as a pilot study, it was based on a small and single-time point sample, which limits the external validation of our findings. However, the positive results suggest a potential benefit derived from of our proposed curriculum. Second, the fact that the participants and professors were surveyed at the end of the semester, may have introduced a recall bias. Finally, there was no control group to compare the differences against our new curriculum. Future studies shall be able to assess the long-term outcomes of the new curriculum in real-world scenarios, and consider the development of new curricula combining biosafe environments, simulations, and real-world scenarios and practices.

CONCLUSION

Our new student-centered curriculum proposal is feasible, appealing, and provides a sound introduction to the principles and procedures of anesthesiology to medical students. Similar educational programs may be widely implemented in the near future, not just in the context of the biosafe post-pandemic era, but as a strong alternative to the traditional anesthesiology curricula.

ETHICAL DISCLOSURES

Ethics committee approval

The Institutional Ethics and Academic Committee of the Universidad de los Andes approved the implementation of the new curriculum during the first semester of 2020, together with a survey administered at the end of the process to publish the results and improve the proposal. Prior to each activity and survey, the students were asked to submit their individual consents.

Protection of human and animal subjects

The authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study. The authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the relevant clinical research ethics committee and with those of the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki).

text in

text in