Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Lenguaje

versão impressa ISSN 0120-3479

Leng. vol.39 no.2 Cali jul./dez. 2011

Verbal processes in student academic writing in Spanish from a systemic functional perspective*

Procesos verbales en la escritura académica estudiantil en español desde una perspectiva sistémico funcional

Processus verbaux concernant l'écriture académique d'étudiants en espagnol depuis la perspective systémique fonctionnelle

Natalia Ignatieva Kosminina

Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, México D.F. - México

E-mail: ignatiev@servidor.unam.mx

Fecha de recepción: 26- 04-2011

Fecha de aceptación: 21-09-2011

* The project Verbal processes in academic writing in the light of systemic functional grammar was discussed and approved by the Academic Counsel of the Department of Applied Linguistics (Foreign Language Centre) in 2010. The project is being carried out with the resources of this Department and it is planned to be finished by 2013. The participants are Natalia Ignatieva (coordinator), Victoria Zamudio, Eleonora Filice, Daniel Rodríguez and Luz Elena Herrero.

Abstract

The aim of this paper is to present a systemic functional analysis of verbal processes in student texts. This work is part of an on-going research project developed at the National Autonomous University of Mexico. The paper is based on literature texts belonging to two genres: question-answer and essay. First, I define the group of verbal processes and determine their frequency. Then I explore the context of their use and identify the participants in the verbal clauses. Finally, I compare the two groups of texts according to their verbal process characteristics.

Key words: text, transitivity, process, participant, projection.

Resumen

El objetivo de este artículo es presentar un análisis sistémico funcional de procesos verbales en los textos estudiantiles. El trabajo forma parte de un proyecto de investigación en curso desarrollado en la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. El artículo está basado en los textos de literatura que pertenecen a dos géneros: pregunta-respuesta y ensayo. Voy a definir el grupo de los procesos verbales y determinar su frecuencia; después exploraré el contexto de su uso e identificaré los participantes en las cláusulas verbales. Finalmente, se comparan los dos grupos de textos de acuerdo con sus características de procesos verbales.

Palabras clave: texto, transitividad, proceso, participante, proyección.

Résumé

L'objectif de cet article est de présenter une analyse systémique fonctionnelle des processus verbaux dans les textes d'étudiants. Ce travail fait partie d'un projet de recherche en cours développé à l'Université Nationale Autonome du Mexique. Cet article est fondé sur des textes qui appartiennent à deux genres: question-réponse et essais. Je vais définir le groupe des processus verbaux et en déterminer leur fréquence; ensuite, je vais explorer leur contexte d'utilisation et identifier les participants dans les phrases verbales. Finalement, on va comparer les deux groupes de textes d'après leurs caractéristiques en tant que processus verbaux.

Mots clés: texte, transitivité, procès, participant, projection.

Introduction

The aim of this paper is to present a systemic functional analysis of verbal processes in student academic writing. This work is part of an on-going research project developed at the National Autonomous University of Mexico which, in turn, is part of the major project Systemics Across Languages (SAL) in its Latin American version1. The corpus is taken from our previous project which investigated the language of humanities in Mexico and the United States2. One of its purposes was to collect student texts from humanistic areas to design a web page which includes the Corpus of Academic Language in Spanish (CLAE, 2009). In this paper I use the Mexican component the CLAE corpus which embraces three areas: literature, history and geography. This paper is based on literature texts belonging to two genres.

First, I will define the group of verbal processes derived from the corpus and determine their frequency in relation to the number of clauses. Then I will explore the context of their use and identify the participants in the verbal clauses. Finally, the two groups of texts will be compared according to their verbal process characteristics and conclusions are drawn.

Theoretical bases

The theory underlying this study is Systemic Functional Linguistics originated by Halliday (1978, 1985, 1994) and developed by other exponents of this trend (Martin, 1985, 1992; Martin & Rose, 2003; Matthiessen, 1995; Thompson, 1996; Ghio & Fernández, 2005; Montemayor-Borsinger, 2009; etc.). One of the principal ideas of this theory is to consider language as a system of subsystems based on their functions derived from the use of the language in its social context.

According to Halliday (2004), language is structured to fulfill three main functions which he denominates metafunctions; these are ideational, interpersonal and textual functions. The ideational function organizes our experience in the exterior and interior world, the interpersonal expresses our interaction with others, and the textual function contextualizes linguistic units and organizes them into a discourse.

These three functions correspond to three systems at the lexico-grammatical level: Transitivity, Mood and Theme, and in this way the system of Transitivity is the realization of the ideational function, while the system of Mood reflects the interpersonal function and the system of Theme represents the textual function. Thus, in terms of meaning potential, "transitivity is the ideational component in the meaning of the clauses"(Halliday, 1976, p.21).

Transitivity is defined as the system that concerns different combinations of participants organized around a process in the clause. It refers to "a way of representing patterns of experience (...) of imposing order on the endless variation and flow of events (Halliday, 1994: 106). In other words, it is the organization of the sentence to express experiential meanings.

The transitivity system construes the world of experience into a set of process types. Halliday first divided processes into three types: "material", "mental" and "relational" (Halliday, 1968), then he added three more types: "verbal", "behavioural" and "existential" (1985), but he considered the original three as the main types while the second group of three was thought of as "borderline" cases. Thus, the category of "verbal" processes is situated on the borderline between "mental" and "relational" processes because a symbolic relationship is constructed in human consciousness and enacted in the form of language like saying, according to Halliday (2004: 171). Matthiessen (1995), however, extended these main types to four (material, mental, relational and verbal). He included verbal processes in this group arguing that verbal processes have their own characteristic traits that set them apart from the other process types. We shall follow Matthiessen's point of view.

Each process type provides its own model or schema for construing a particular domain of experience (Halliday, 2004, p.170). This schema concerns the roles of the participants of the clauses with a particular type of process. For example, material processes usually imply the existence of an Actor as the first participant and a Goal as the second participant (e. g. Bill smashed the glass). Verbal processes have their own schema for construing the clause (Lavid, Arús& Zamorano-Mansilla, 2010, p.135-7).

Methodology

As already mentioned, I used the CLAE corpus, i. e. student texts collected at the Faculty of Philosophy and Arts, of the National Autonomous University of Mexico. This paper is based only on literature texts, from the Department of Modern Languages and Literature. There are 22 of them, belonging to two genres: question-answer (15) and essay (7). The first genre is part of a question-answer exam written in class while the second is part of a term assignment prepared out of class. I will describe the two genres separately and then compare them.

Both quantitative and qualitative analysis will be applied to our corpus: quantitatively I will determine the numerical values for verbal processes and qualitatively I will try to define the lexico-semantic group of verbs of saying and explore the context in which they are used.

Text Analysis

Question-answer texts (Q-A texts)

We shall begin our analysis by considering student texts of a question-answer type3, written in class as part of the term examination. There are fifteen texts and their main topic is the novel Don Quijote by Cervantes.

First, I counted the number of clauses in each text in order to have it as a point of reference. Only finite clauses4 were taken into consideration, i.e. I did not count non-finite clauses considering them as parts of finite clauses. Then I looked for all instances of verbal processes in the texts and summed them up in order to have a total number of verbal processes. The results can be found in Table 1.

We can see that the total number of clauses is 427 and there are 108 cases of verbal processes, which seems a rather large number. It amounts to 25.3% in relation to the total number of clauses.

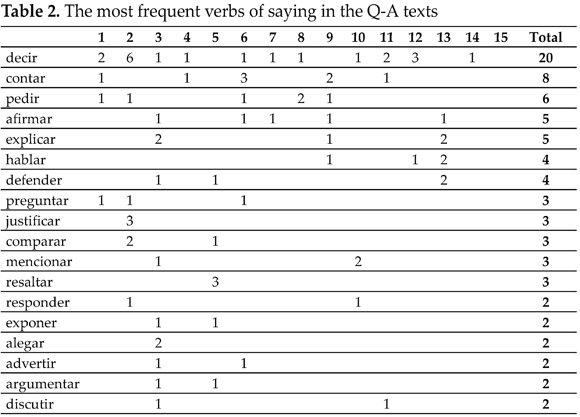

Then, I tried to determine a lexicosemantic group of words that denote the process of "saying". The resulting data can be found in Table 2, Table 11 and Figure 1. Table 2 includes only the verbs used more than once in Q-A texts.

The first row in Table 2 presents the fifteen texts while the first column provides the verbs of the texts in decreasing order of frequency, from the most frequent to those that were used more than once. As it may be expected, the first place is occupied by the verb decir say with 20 uses which confirms its unmarked character in the group. The second most frequent verb is contar tell with 8 uses, and the third is pedir ask for with 6 uses. All in all, Table 2 includes 18 different verbs.

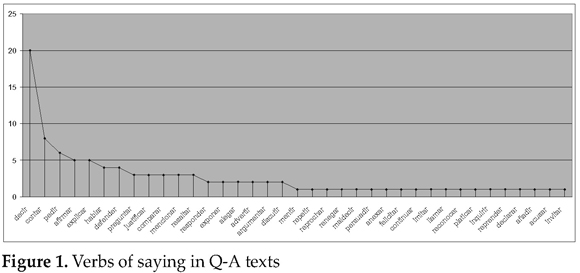

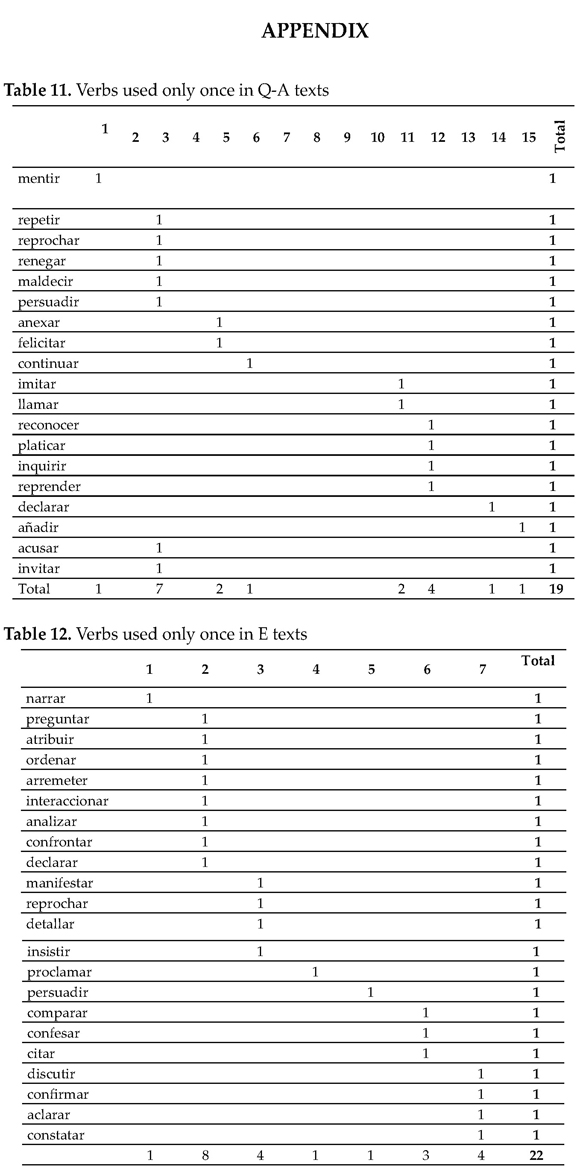

Table 11 (See Appendix) shows other verbs from the same group used only once in the Q-A texts, among them verbs like mentir lie, repetir repeat, reprochar reproach, etc. There are 19 verbs in this Table. If we sum up the verbs in Table 2 and Table X we have 37 verbs in the group of "saying" which are represented in Figure 1.

Besides verbs, I singled out verbal expressions which denote verbal processes. The peculiarity of these verbal expressions or phrases is that one member of this phrase is partially "empty" (from the semantic point of view); therefore, it needs a complement to transmit its meaning, for example: hacer el discursodeliver a speech, etc.

The whole list of the verbal expressions used in Q-A texts is as follows:

* hacer el discurso (3)5 deliver a speech

* situar en el discurso (3) "accomodate in a discourse"

* hacer énfasis (5) "make emphasis"

* dar el discurso (5) "give a discourse"

* dar voces (5) "give voice"

* lanzar una advertencia (5), "send a warning"

* manifestar el deseo (5) "manifest a desire"

* hacer referencia (7) "make reference"

Thus, the lexicosemantic group denoting the process of "saying" in our corpus of Q-A texts consists of 45, including 37 verbs and 8 verbal expressions. The dominant member of this group is par excellence the verb decir say.

Essay texts (E texts)

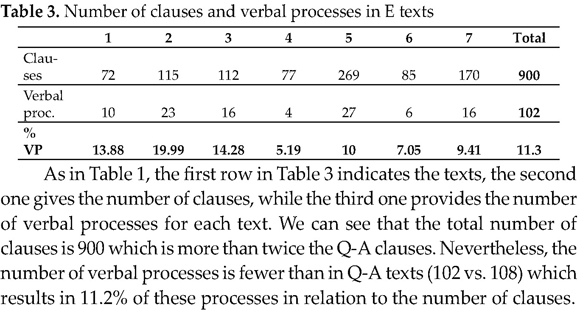

Now I shall analyze the texts belonging to the essay genre. These are texts prepared and written out of class as part of a term assignment. As mentioned above, there are seven of them. These texts are larger than the Q-A texts and although they are fewer in number, they contain more clauses, as Table 3 shows.

As in Table 1, the first row in Table 3 indicates the texts, the second one gives the number of clauses, while the third one provides the number of verbal processes for each text. We can see that the total number of clauses is 900 which is more than twice the Q-A clauses. Nevertheless, the number of verbal processes is fewer than in Q-A texts (102 vs. 108) which results in 11.2% of these processes in relation to the number of clauses.

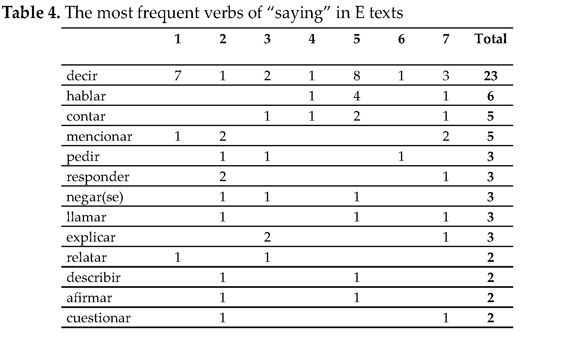

I shall explore now the lexical group of verbs of "saying" used in the essays and I proceed the same way it was done with the Q-A texts.

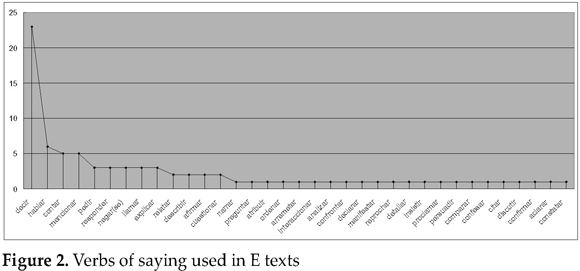

Table 4 presents the subgroup within this lexical group consisting of 13 verbs which were used more than once. We can notice that the most frequent verb in this group is decir say, with 23 uses. Its frequency is almost four times greater than the following verb. The second place in frequency is occupied by the verb hablar speak with six uses and in the third place there are two verbs: contar tell and mencionar mention with five uses each.

Another subgroup includes 22 verbs, all of which were used only once in the essay type texts (See Appendix, Table 12). The two subgroups (Table 4 and Table 12), together give us an account of 35 verbs which are presented in Figure 2.

As for the verbal expressions or phrases which denote verbal processes, we have the following list for E texts:

* hacer notar (2) "make it clear"

* llegar a la conclusión (2) "arrive at the conclusion"

* hacer una petición (3) "make a petition"

* hacer hincapié (3, 5) "lay stress"

* dar razones (3, 5) "give reasons"

* dirigirse con las palabras (3) "direct one'swords"

* hacer mención (5) "make mention"

* revelar secretos (5), "reveal secrets"

* dar gracias (5) "give thanks"

* comenzar el relato (5) "begin a story"

* vaticinar hechos (5) "foretell facts"

* pedir perdón (5) "ask somebody'spardon"

* hacer una exaltación (6) "make an exclamation"

* tocar temas (7) "touch topics".

The number of different verbal expressions is 15. Thus, the lexicosemantic group of saying for E texts consists of 50 members: 35 verbs and 15 verbal expressions.

Participants in the verbal clauses

The most important participant in verbal clauses is the Sayer (Halliday, 2004: 252), in fact, it is the only necessary participant in the act of saying or speaking, e.g.:

(1) Marcela expone las razones...(Q-A 3)

Marcela exposes the reasons"

(2) La novela dice que es bella. (E 1)

The novel says she is beautiful.

In (1) Marcela is the Sayer. As can be seen in (2), the Sayer sometimes may be a non human participant. Another important participant is the Receiver which is usually present in the clause and is typically human like nos in (3) or le...Lotarioin (4):

(3) ...la voz nos cuenta de un viaje. (Q-A 9)

...the voice tells us about a journey.

(4) Anselmo le hace a Lotario una impertinente petición. (E 3)

Anselmo makes Lotario an impertinent petition.

In certain cases, and only with some verbs, the verbal process may be directed at still another participant: the Target. In this situation some entity is "targeted by the process of saying" (Halliday, 2004: 256), e.g.:

(5) Don Quijote lo felicita en su decisión. (Q-A 5)

Don Quijote congratulates him on his decision.

(6) Montesinos compara a Dulcinea con Belerma. (E 6)

Montesinos compares Dulcinea with Belerma.

Both the Receiver and the Target are usually expressed by a clitic and/or a prepositional phrase with the preposition a, as can be seen in the examples above (3-6).

The other kind of participant that may appear in a verbal clause refers to the message itself. This is called the Verbiage and is usually expressed by a noun group, e.g.:

(7) ...él es capaz de mencionar todos los nombres. (Q-A 10)

...he is capable of mentioning all the names.

(8) ...le han contado las mentiras. (E 5)

...he was told the lies.

The Verbiage may express the content of what is said as in (7) or it may consist of a name for the language itself as in (8). Closely related to the Verbiage is a category of circumstance called Matter. It refers to the content of the message when it is expressed by a prepositional phrase, e.g.:

(9) Don Quijote habla sobre su ocupación. (Q-A 13)

Don Quijote speaks of his occupation.

(10) Unamuno hablaba del fenómeno. (E 4)

Unamuno spoke of the phenomenon.

Among the participants analyzed above only the Sayer and the Target are considered to be "direct" by Halliday while the Reciever, the Verbiage and the Matter are "oblique" participants.

Another way of transmitting what is said is represented by means of direct or indirect speech. In (11) we deal with two clauses, only the primary clause is a verbal one, the next one is a reported clause, the relationship between them being hypotactic. In (12) there is also a clause complex but this time with a paratactic relation. Besides, the second clause is now a quoted one.

(11) Sancho le dice que es por encantamiento. (Q-A 12)

Sancho tells him it is for enchantment.

(12) Cervantes nos dice "En resolución, él se enfrascó..."(E 5)

Cervantes tells us In resolution, he sank....

The content of the message is called now a "locution" (direct or indirect), but it is not analyzed as a participant in the verbal process because it is found outside the verbal clause. When the message is expressed through reported speech, the logico-semantic relation between a primary and a secondary member of a clause nexus is called "projection" in functional grammar (Halliday, 2004: 376). This relationship between the two members is like the one "between a picture (projected clause) and its frame (projecting clause): together they make up a single complex unit, but neither is actually part of the other" (Thompson, 2004: 103).

To sum up, I have tried to analyze the corpus in terms of participants and I added "the locution" to my analysis because although the locution is syntactically outside the main clause, it has strong semantic ties with the verbal process and some authors even insist on treating it as some sort of "Verbiage".

Figure 3 shows all the components of our analysis which fall into three parts: processes, participants in the verbal clause, and locutions (projections).

Participant and projection analysis in the verbal clauses in Q-A texts

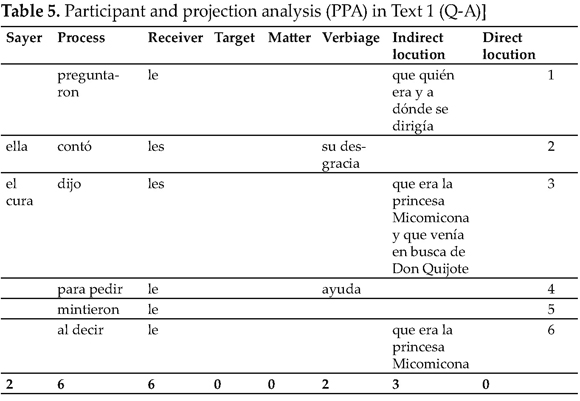

I applied the analysis summarized in Scheme 1 to all the texts of Q-A type. I shall present Text 1 in Table 5 as an illustration of our analysis. Only the clauses with verbal processes were included in the Table.

In Table 5 it can be seen that Text 1 (Q-A) has 6 clauses with verbal processes (see the last column of the Table). The Sayer is expressed only in two clauses, the rest of the clauses either have an implicit Sayer or it is unknown. As for the Reciever, it is realized in all the clauses. On the contrary, the Target and the Matter are manifested in none of them. The Verbiage is expressed in two clauses and we have three cases of indirect locutions where the verbal clause is followed by a projected clause containing indirect speech.

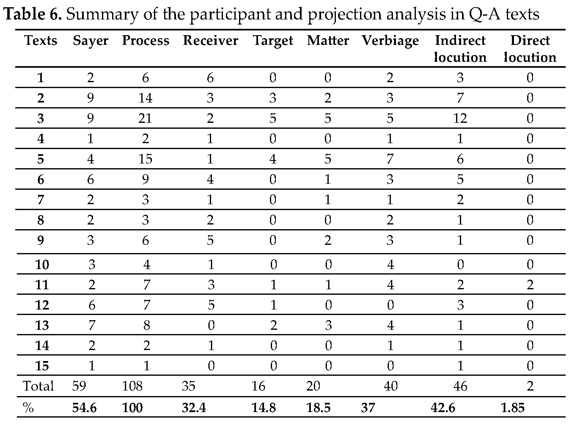

Table 6 presents a summary of the participant and projection analysis in all the texts of the Q-A type.

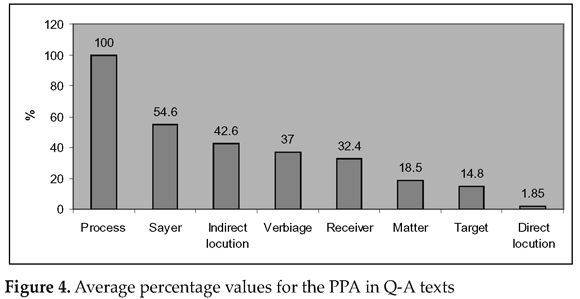

The average percentage values for the participant and projection analysis appear in Figure 4. These values are organized in decreasing order.

Participant and projection analysis in the verbal clauses in E texts

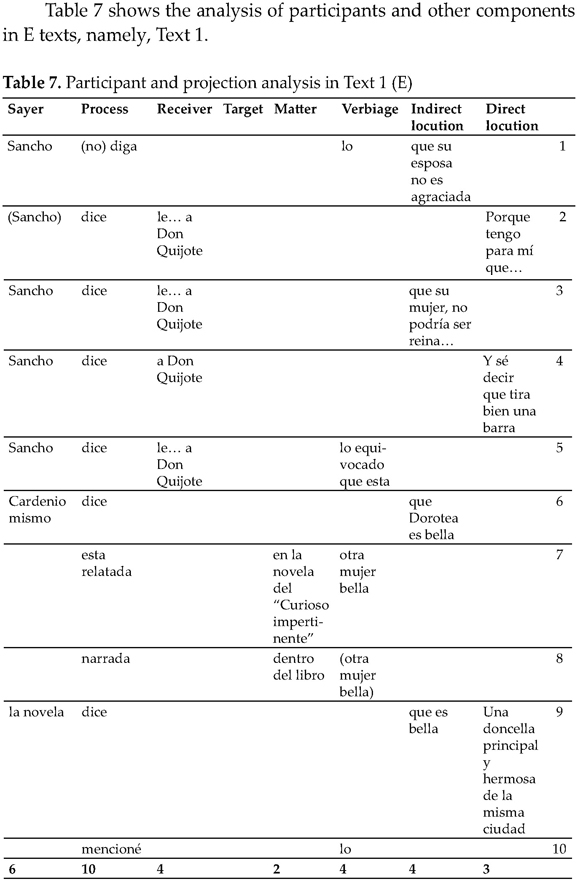

Table 7 shows the analysis of participants and other components in E texts, namely, Text 1.

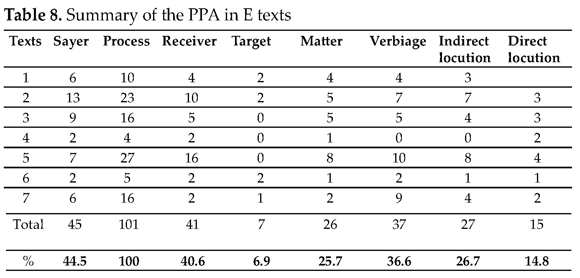

The summary of the data analysis applied to all the texts of the essay type can be observed in Table 8.

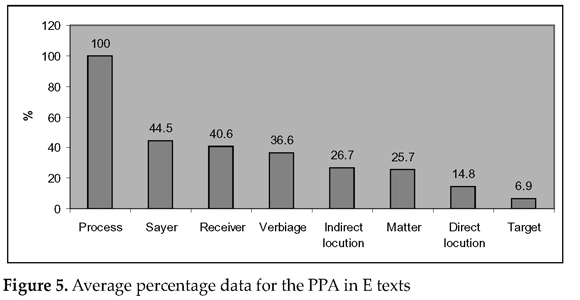

To visually consider the decreasing order of all the components in the PPA for E texts we present the average data percentage in Figure 5.

Genre comparison between Q-A and E texts

I shall compare the results of our analysis in relation to the two genres.

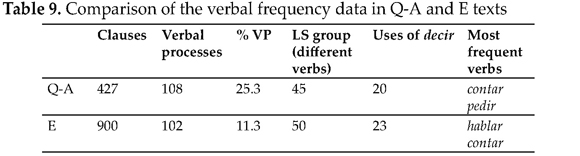

In Table 9 we can see that the percentage of verbal processes in Q-A texts is more than twice the size of that of E texts. This may reflect the fact that the Q-A texts written in class with a limit of time have a more colloquial quality as compared to the E texts which are more thoroughly prepared and checked at home.

On the other hand, the last three columns on the right in Table 9 show a certain similarity between the two genres. Thus, the lexicosemantic group of saying, including different verbs and verbal expressions, amounts to 45 in Q-A texts and 50 in E texts; the frequency of the default verb decir is also similar (20 vs. 23). As for the most frequent verbs following decir, there is also a coincidence in one of the two verbs: contar tell.

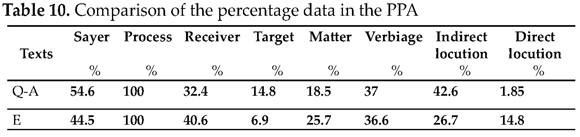

Now I shall compare the data of our participant and projection analysis of the two genres as presented in Table 10.

At first sight it seems that with the exception of the Verbiage that has similar numbers in both type of texts, the rest of the data differ between the Q-A and E texts. Nevertheless, one can find some other similarities, for example, the Receiver and the Target are different in numerical value, but if we take into account that these two participants usually exclude each other, i.e. the verbs that may have the Target as a participant typically are not associated with the Receiver and vice versa, then we can see that the sum of the two is almost equal: 47.2 in Q-A vs. 47.5 in E texts. That means that the realization of the second (usually human) participant in the verbal clause is similar in both types of texts, the difference being in the fact that Q-A texts used more verbs that require the Target as the second participant.

Another difference between the two genres consists in a considerable increase of direct locutions in the E texts (14.8 vs. 1.85), explained by the fact that being prepared at home, the E texts have all sorts of quotations taken from different literary sources while the Q-A texts being written in class, have almost none of these quotations because of the lack of sources at hand. This lack is made up for by indirect quotations which are more numerous for Q-A texts than for E texts. Curiously enough, if we sum up the direct and indirect locutions for each genre, the difference between them is not significant: 44.45 vs. 41.5.

Finally, one may pay attention to the fact that the Sayer is expressed 10 % more often in Q-A texts than in E texts. It may be accounted for by a larger number of impersonal sentences in E texts which are a marker of a more objective and neutral style.

Conclusions

This paper reports the preliminary results of an on-going project. It explores verbal process behavior in two genres belonging to academic register: question answer and essay. First, verbal process frequency was established and I discovered that this index was considerably higher (more than double) for Q-A texts as compared to the E texts. The explanation of this phenomenon may be derived from the more informal and more colloquial character of the former in comparison with the latter. This coincides with our previous data in the analysis of these two genres (Ignatieva 2008a; 2008b).

Then I determined the lexicosemantic group of verbs of "saying" for each genre of our corpus. There were slight differences between the two groups in numbers and the composition, but in both cases the verb decir was singled out as the unmarked and dominant member of the group.

I identified all the participants and other important components in the verbal clauses and then applied the participant and projection analysis to the Q-A and E texts and compared the results. The two types of texts showed both differences and similarities. Thus, they were different in relation to the use of direct and indirect speech which is explained by distinct conditions of writing in both cases (one in class and the other at home). Another difference concerns the fact that E texts have more implicit Sayers that Q-A texts which, we think, is due to a more extensive use of impersonal clauses in E texts. This, in turn, underlines the more objective character of E texts as compared to Q-A texts.

It is hoped that these preliminary results can be enriched with a further exploration of our corpus since we are still in the initial phase of our project.

Foot Notes

1. Although various individual and collective projects entering SAL are under way in several countries (Argentina, Brazil and Mexico), there are almost no published works yet. The only reference I could find is an article by Barbara and Macêdo (2011) based on the analysis of Portuguese verbal processes which has just been published.

2. The project The Language of the Humanities in Mexico and the United States: A Systemic Functional Analysis (2006-10) was carried out thanks to a Collaborative Grant from the University of California Institute for Mexico and the United States (UC MEXUS) and the National Counsel of Mexico for Science and Technology (CONACYT).

3. The questions in the exam were open, e. g. Describe la relación de Don Quijote con DulcineaDescribe the relationship of Don Quijote and Dulcinea or Habla del encantamiento de DulcineaSpeak about Dulcineas enchantment, etc.

4. Finite clauses are those that contain a finite verbal element expressing tense or modality (Halliday 2004: 111) while non-finite clauses contain no finite element but they have other verbal forms such as infinitives, gerunds or participles.

5. The number in brackets indicates the text where the verbal expression is used.

References

Barbara, L. y Macêdo de-Macêdo, C.M. (2011). Processos verbais em artigos acadêmicos: Padrões de realização da mensagem. En L. Barabara & E. Moyano (Comps.). Textos e linguagem acadêmica: Exploraçõessistêmicafuncionais em espanhol e português (pp.213-31). Campinas - SP, Brasil: Mercado de Letras. [ Links ]

CLAE (2009). El lenguaje académico en español. Análisis binacional de textos en las humanidades. Consultado el 10/06/2010 en http://www.lenguajeacademico.info [ Links ]

Ghio, E. y Fernández, M.D. (2005). Manual de lingüística sistémico funcional: El enfoque de M. A. K. Halliday y R. Hasan: Aplicaciones a la lengua española. Santa Fe, Argentina: Universidad Nacional del Litoral. [ Links ]

Halliday, M.A.K. (1968). Notes on transitivity and theme in English. Journal of Linguistics 4, (pp. 179-215). [ Links ]

___ (1976). System and function in language. London, UK: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

___ (1978). Language as social semiotic: The social interpretation of language and meaning. Londres, UK: Arnold. [ Links ]

___ (1985). Spoken and written language. Geelong - Vic., Australia: Deakin University Press. [ Links ]

___ (1994). An introduction to functional grammar. 2 ed. London, UK: Arnold. [ Links ]

___ (2004). An introduction to functional grammar. 3 ed. London, UK: Arnold. [ Links ]

Ignatieva, N. (2008a). Question-answer as a genre in students' academic writing in Spanish. En C. Wu, C. Matthiessen & M. Herke (Comps.). Proceedings of ISFC 35: Voices around the World (pp. 61-66). Sydney, Australia: Macquarie University. [ Links ]

Ignatieva, N. (2008b). Descripción sistémico-funcional de la escritura académica estudiantil en español. Núcleo (Revista de la Universidad Central de Venezuela) 25, (pp. 173-195). [ Links ]

Lavid, J., Arús, J. & Zamorano-Mansilla, J. R. (2010). Systemic functional grammar of Spanish: A contrastive study with English. London - New York, UK - USA: Continuum. [ Links ]

Martin, J. (1985). Factual writing: Exploring and challenging social reality. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Martin, J. (1992). English text: System and structure. Amsterdam, Netherlands: John Benjamins. [ Links ]

Martin, J. & Rose, D. (2003). Working with discourse: Meaning beyond the clause. London - New York, UK - USA: Continuum. [ Links ]

Matthiessen, C.M.I.M. (1995). Lexico-grammatical cartography: English systems. Tokyo, Japan: International Language Sciences. [ Links ]

Montemayor-Borsinger, A. (2009). Tema: Una perspectiva funcional de la organización del discurso. Buenos Aires, Argentina: Universidad de Buenos Aires, Eudeba. [ Links ]

Thompson, G. (2004). Introducing functional grammar. London, UK: Arnold. [ Links ]