INTRODUCTION

“Reading is proud to hear Spanish spoken in

public. Aren’t you glad this isn’t Hazleton?”

- Tom McMahon

Prior to the early 1990s, migration was a well-regulated phenomenon. For different reasons, people left their country and settled in another, adapting where necessary to assimilate into their new host society. However, growing instability in many parts of the world since the end of the Cold War has changed patterns of human mobility and the way in which people plan and/or organize their lives. This has also been greatly impacted by changes in economic and technological infrastructure as constituent parts of larger processes associated with globalization (cf. Vertovec, 2007, 2010, 2011). As such, the outcome has been an intensification of diversity at every level-ethnic, social, cultural, and economic-in societies throughout the world (Blommaert, 2013). Yet the ability to integrate with the new host society depends upon widespread, shared assumptions of uniformity, categorizability, transparency, and fixedness (cf. Blommaert, 2010, p. 26). To that end, language has been used by the state as a tool to divide and discriminate against immigrants, which is particularly salient in some American cities.

As such, Lou Barletta, the former three-term mayor of Hazleton, Pennsylvania and now a Congressional Representative, introduced a city ordinance in 2006 by issuing the following cautionary statement: “Anyone can walk into the city right now, give the landlord $400, put their bags in a room, and go shoot somebody in the head tomorrow” (Steil & Ridgley, 2012, p. 1039). Such a remark was not made in response to an exponential increase in crime1 but rather to a perceived rise in criminal acts involving illegal immigrants, specifically those from Spanish-speaking nations. As such, Barletta was perpetuating what has come to be identified as the “Latino Threat Narrative” (cf. Chavez, 2013), i.e. the notion that Latinos-as opposed to other immigrant groups-are less likely to engage culturally, linguistically, and politically with non-Latinos; and that these groups tend to be much more traditional, much less educated, more prone to self-segregation, and more frequently couriers of crime. Consequently, Barletta’s administration further proposed, unsurprisingly given his other remarks, that English become the official, singular language of the city, a stance he believed was not racist due to equal exclusion2.

Assuming such a position had local and international consequences. First, the city was on the receiving end of a lawsuit that alleged such legislation was unconstitutional and discriminatory (cf. United States Court of Appeals, 2010). Ultimately, this lawsuit would result in a fine of over one million dollars. Second, Barletta became the target of other mayors-whose positions were markedly different-from nearby cities with similar demographics. For instance, Tom McMahon, the former two-term mayor of Reading, Pennsylvania, responded to his northern counterpart’s approach by stating, “Reading is proud to hear Spanish spoken in public. Aren’t you glad this isn’t Hazleton?” Third, the city became situated within and the subject of academic discourse on institutionalized racism and the place of Latinos in twenty-first century white America (see for example, Longazel, 2016; Steil & Ridgley, 2012).

Nevertheless, it is important to understand why the administrative response to (il)legal immigration in Hazleton has been so swift. Located at the southern edge of Luzerne County in northeastern Pennsylvania, Hazleton has a population of approximately twenty-five thousand residents. The surrounding towns-and the historic city itself-are characterized largely as being demographically homogeneous; in fact, the majority of the residents in the metropolitan area historically descend from Eastern European immigrants whose families earned a sustainable living through employment in the anthracite industry, which accelerated in the region during the late nineteenth century but ceased to exist around the early twentieth century. Consequently, the overwhelmingly white population of Hazleton has watched their city experience a slow death as a result of the loss of the coal mining industry. Moreover, the population decreased as residents migrated from the city-to be replaced gradually in the 1990s and then exponentially in the 2000s by a population increasingly self-identifying as Latino, which is illustrated in Table 1 below.

Table 1 Dominant At-Home Language Use in Hazleton, PA

| Year | Total Population | English | Non-English | Spanish | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 20,400 | 16,414 | 80.46% | 3,986 | 19.54% | 3,986 | 19.54% |

| 2010 | 23,313 | 17,229 | 73.90% | 6,084 | 26.10% | 6,084 | 26.10% |

| 2011 | 23,444 | 16,852 | 71.88% | 6,592 | 28.12% | 6,592 | 28.12% |

| 2012 | 23,496 | 15,670 | 66.69% | 7,826 | 33.31% | 7,826 | 33.31% |

| 2013 | 23,557 | 14,771 | 62.70% | 8,786 | 37.30% | 8,786 | 37.30% |

| 2014 | 23,393 | 13,916 | 59.49% | 9,477 | 40.51% | 9,477 | 40.51% |

| 2015 | 23,333 | 12,917 | 55.36% | 10,416 | 44.64% | 10,416 | 44.64% |

| 2016 | 23,280 | 12,533 | 53.84% | 11,363 | 48.81% | 10,747 | 46.16% |

Source: Adapted from the American Community Survey (United States Census Bureau, 2019)

Similarly, Table 2 exemplifies the shift in the language of daily communication. Consequently, the data in both ultimately contribute to the perceived risks or fear that Barletta perpetuates through ascription to the Latino Threat Narrative.

Table 2 Latino and Non-Latino Identity in Hazleton, PA

| Year | Latino | Non-Latino |

|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 0.51% | 99.49% |

| 1990 | 1.02% | 98.98% |

| 2000 | 4.85% | 95.15% |

| 2010 | 31.50% | 68.50% |

| 2011 | 33.50% | 66.50% |

| 2012 | 38.60% | 61.40% |

| 2013 | 42.50% | 57.50% |

| 2014 | 46.20% | 53.80% |

| 2015 | 50.30% | 49.70% |

| 2016 | 52.20% | 47.80% |

Source: Adapted from the American Community Survey (United States Census Bureau, 2019)

In order to investigate precisely how these data relate to the written usage of the Spanish language in Hazleton, Pennsylvania, this paper is divided into a further four sections. The second section reviews the previous scholarship on linguistic landscapes generally and also examines the methodologies and results of particular case studies on Spanish language usage in (non-)urban settings in the United States. The third section presents the setting and methodology for the present study before providing a cursory attempt at understanding the data through word frequency and encoding. The fourth section examines a sample of the signs in this corpus to define precisely how the type and extent of language usage not only reflect the needs, desires, interests, and identity of the community, but also index members of that same community geopolitically, temporally, and linguistically. Finally, the fifth section provides a brief conclusion and presents areas for further consideration and additional research.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Linguistic Landscapes

Sebba (2010) notes that the field of linguistic landscape studies “has evolved rapidly [… ] and currently has no clear orthodoxy or theoretical core; rather, most researchers who associate themselves with the approach acknowledge a few key works” (p. 73). As such, although many scholars disagree on the methodology to be employed and, in particular, the criteria for inclusion or exclusion of particular linguistic data, it is without doubt that the most commonly referenced-and one of the earliest-definitions is found in Landry and Bourhis (1997), who regard the linguistic landscape as the combination of “the language of public road signs, advertising billboards, street names, place names, commercial shop signs, and public signs on government buildings” (p. 25). Gorter (2006) and Kasanga (2012), among others, extend this definition by acknowledging that even graffiti, restaurant menus, and spray-painted manhole covers contribute to the description of the linguistic landscape. Nevertheless, as a result of the breadth of viable materials and media, in addition to the seemingly all-encompassing descriptions, Shohamy and Gorter (2009) attempt to collapse the definitions into one that is more general and includes non-textual linguistic data: “language in the environment, words and images displayed and exposed in public spaces” (p. 1). But then, any ethnographically informed fieldwork that focuses on everyday language usage could examine these media; thus, the parameters must be seemingly redefined at the level of the individual project and not of the field.

On the other hand, Blommaert (2013) studies linguistic landscapes from a complexity perspective, itself rooted in the concept of superdiversity, a tremendous increase of societal diversity (cf. Vertovec, 2007, 2010). This ‘diversity within diversity,’ as it has been frequently described, is the result of new and more complex forms of migration and more technologically sophisticated forms of communication. The outcome of these two forces has been “an escalation of ethnic, social, cultural and economic diversity in societies almost everywhere” (Blommaert, 2013, p. 5). He further argues that language appears to take a privileged place in defining the impact of superdiversity. Investigating his own neighborhood in Antwerp, Belgium, he demonstrates how multilingual signs serve as the primary illustration of the social, cultural, and political histories of a place. Thus, combining ethnographic observations with linguistic data, signs in public spaces tell the story of the complex nature and identity of communities, as the signs of different immigrant groups provide evidence for the evolution of their adaptation, settlement processes, and daily experiences.

Previous Studies on Spanish-Language Signs

Given its role as one of the world’s major languages, it is unsurprising that dozens of previous studies exist that have considered the role of Spanish within communities in the United States. In fact, although there are even entire textbooks on the use of Spanish (see e.g. Otheguy & Zentella, 2012), the present study is much more concerned with case studies that are more analogous to the context of Hazleton, Pennsylvania.

Hassa and Krajcik (2016) engage language policy and ideology in New York City, in particular by working with(in) the Dominican community and by examining the Spanish-language linguistic landscape. They collected a total of 646 signs from over four-hundred businesses and coded these according to language, context, and location. It is important to note that they only excluded signs with proper nouns and did document signs regardless of language, collecting messages that were monolingual, bilingual, or even trilingual. The most important contribution of this study, however, is their argument that a correlation exists between the monolingual (Spanish) signs and the affordability of the corresponding business. Finally, a brief excursion into comparing the number of words on each sign is undertaken, in order to describe the frequency of a particular language in the linguistic landscape. Nevertheless, this seems generally to be a fruitless endeavor, as no qualifiers are given concerning the oftentimes more periphrastic nature of expressions in Spanish (as opposed to English), thus leading an unfamiliar reader to assume that Spanish is more common despite the same message being conveyed.

Lyons and Rodriguez-Ordóñez (2017) also examine Spanish-language signs, albeit in Pilsen, a neighborhood of Chicago. They begin by remarking that the signs they investigated reflect and reinforce local Hispanic authenticity; to that end, they disregard official translations, house names, and street names in their corpus. As opposed to constructing a taxonomy of sign types or functions, they instead classify each sign according to the same criteria used by Hassa and Krajcik (2016). However, the ’context’ previously mentioned is here reconstituted as a discursive frame (cf. Tannen, 1993). As a result, the frame carries a specific functional load for its audience; for instance, a sign coded as “recent immigrant” is more likely to offer a specific service or fulfill a certain need for a new arrival to the country.

Yanguas (2009) focuses on two neighborhoods in the northwestern part of Washington, D.C., that were historically considered and are contemporaneously identified as overwhelmingly Latino. He begins by considering language policy-within the United States generally and the District of Columbia specifically-before proceeding to a description of the monolingual and bilingual signs found throughout the city. As this study reinforces the notion that institutionalized policies concerning language usage can positively or negatively affect language use throughout the city, Yanguas (2009) sought to uncover how the English-first policy of D.C. impacted all types of signs, including government translations, street signs, and translations from companies like H&R Block and McDonalds. Nonetheless, he argues somewhat predictably that the local practices of Latinos (i.e. the continued use of Spanish in everyday life) are the cause of such signs.

Finally, while the previous studies have contemplated the role of Spanish in primarily Latino neighborhoods in urban environments, Troyer et al. (2015) instead present a mixed methods study of the use of the Spanish language in a rural town of nine thousand people in Independence, Oregon. Approximately thirty-five percent of the population in the town identifies as Latino; as a result, they attempted to uncover the extent of the use of the language by using quantitative (i.e. counting and classifying almost five hundred signs) and qualitative (i.e. conducting eight interviews in Spanish and/or English) methods. Based on their results, they concluded that the community avoided the use of Spanish to conceal their heritage, due to the anti-Spanish sentiment in the country.

METHODOLOGY AND DATA

As Chavez (2013) explains, the Latino Threat Narrative is ideologically produced based on the “formation or cluster of ideas, images, and practices that construct knowledge of, ways of talking about, and forms of conduct associated with a particular topic, social activity, or institutional site in society.” (pp. 24-25). Consequently, the ideology underpinning this narrative rests upon the assumption that there exists an accurate, undeniable feedback loop between the perception of Latinos and the reality of their presence. In the case of Hazleton, Pennsylvania, where the local government has indicated with remarkable clarity their generalized opposition to Latinos within urban limits, one might expect a review of criminal activity to demonstrate a statistically significant correlation between two decades of non-white immigration into the city and a rise in crime. Ultimately, the data do not support this belief and, in fact, crime has decreased remarkably in recent years. Consequently, the perception and reality do not match in this regard.

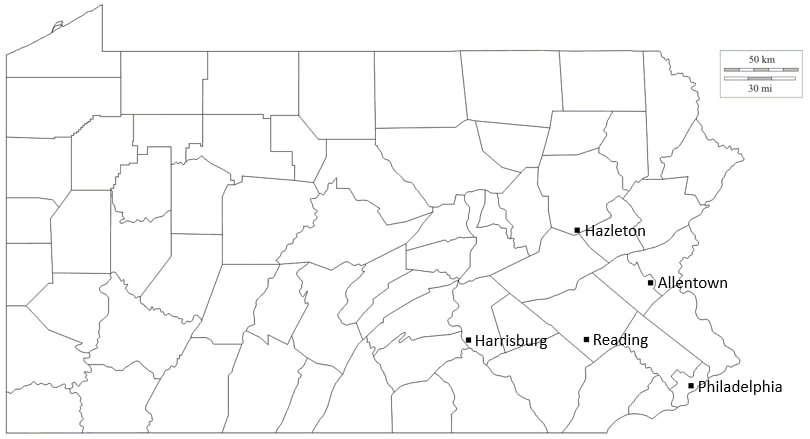

Still, this perception could be informed by visible culture in the city, particularly through the use of written Spanish in public spaces. Consequently, the present study considers the use of the Spanish language on signs in the downtown area of Hazleton to broadly describe the extent to which it is used and more generally to demarcate the signs3 according to utility. To this end, the immediate goals are both sociological and linguistic in nature: Although the recorded signs are documented and categorized for descriptive purposes, the explanatory nature of our findings is specific to the Latino community of Hazleton and not inherently generalizable to other Spanish-speaking communities in the USA nor employed a priori in modifying the theoretical underpinnings of linguistic landscape studies more generally. Thus, we have undertaken here a case study and ‘close reading’ of a sample of these signs (n=10, N=41) to describe and explain that which is observable strictly in the context of northeastern Pennsylvania (see Figure 1 for the precise location of Hazleton).

Given the regulated nature of public spaces, signs are inherently politicized and highly contested. As Blommaert (2013) explains, “Signs will contribute to the organization and regulation of that space by defining addressees and selecting audiences, and by imposing particular restrictions, offering invitations, articulating norms of conduct and so on to these selected audiences” (p. 40). Therefore, it should be understood that the present study presupposes the presence of Latinos within the city and does not examine the signs in order simply to legitimize their presence, but rather to identify the extent and most common functions of Spanish written in public spaces, viz. to analyze how such communication in public space is or can be connected to social structures, power, and hierarchies (cf. Coupland & Garret, 2010) or individual and collective identity.

In pursuit of this task, a total of forty-one distinct signs were documented on the one and a half mile stretch of Wyoming Street, extending from the southernmost junction at Birch Knoll Drive to the northernmost junction at East Ninth Street. It should be noted that these forty-one signs constitute the totality of Spanish-language signs on this street, which is widely believed to validate and reify Hispanidad4. For instance, Frantz (2012) of Penn Live remarked that this street was “bustling with Hispanic businesses, while Broad Street-once the center of the city’s commerce-is languishing.” (para. 18). This perception did not fade even four years later when Matza (2016) of The Philadelphia Inquirer noted that “the dying Wyoming Street commercial corridor has [been] revived.” (para. 19). Although the street was calm and quiet during our fieldwork, there was certainly a remarkable difference both in the number and types of businesses found on Wyoming Street.

An initial, cursory examination of these forty-one signs, which together comprise a corpus of approximately one-thousand words, suggests that there are quite unambiguous objectives for and functional utility in these messages. As seen in Table 3 below, there is significant overlap regarding frequency, whether function words are included or excluded. In fact, it is readily apparent based on occurrence alone that the immediate goal of these signs is to remain connected locally and globally through courier services, translation services, notaries, and technology. Finally, since Hazleton is an incorporated city, there are unsurprisingly also commonly occurring lexical items that refer to food, shopping, and parking, themes which are examined in greater detail in the following section.

Table 3 Word Frequencies

| All Words | Only Content Words | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | de | 57 | 5.38% | envios | 9 | 0.85% |

| 2. | y | 24 | 2.26% | venta | 7 | 0.66% |

| 3. | la | 14 | 1.32% | dinero | 7 | 0.66% |

| 4. | a | 14 | 1.32% | celulares | 7 | 0.66% |

| 5. | para | 13 | 1.23% | traducciones | 6 | 0.57% |

| 6. | los | 12 | 1.13% | sabado | 6 | 0.57% |

| 7. | pm | 10 | 0.94% | productos | 6 | 0.57% |

| 8. | por | 9 | 0.85% | pollo | 6 | 0.57% |

| 9. | envios | 9 | 0.85% | notario | 6 | 0.57% |

| 10. | mas | 8 | 0.75% | mes | 6 | 0.57% |

| 11. | el | 8 | 0.75% | tax | 5 | 0.47% |

| 12. | venta | 7 | 0.66% | restaurant | 5 | 0.47% |

| 13, | dinero | 7 | 0.66% | hazleton | 5 | 0.47% |

| 14. | celulares | 7 | 0.66% | copias | 5 | 0.47% |

| 15. | tu | 6 | 0.57% | velocidad | 4 | 0.38% |

| TOTAL: | 205 | 19.33% | TOTAL: | 90 | 8.49% | |

Unfortunately, a concordance search does not yield significantly informative results with such a small corpus, and a frequency count alone cannot possibly characterize a sign without additional textual or visual context. For instance, one sign contains a message to warn would-be burglars against engaging in criminal activity, yet the presence of such a message does not naturally index the business where it is located, i.e. the exterior glass window of a small store primarily selling school supplies for local primary and secondary school students. Additionally, this message is a direct translation of the corresponding English message, which indicates that the patrons of this store could reasonably be speakers of any language5. As a result, it became clear at this stage that each sign would need to be evaluated individually.

After walking down the length of the street on both sides and photographing, digitizing, and transcribing the forty-one signs, they were classified according to the objective or intended goal of each message. Because each sign may have contained more than one message (oftentimes multiple single, distinct words or common multiple-word concatenations), this resulted in a greater number of categorized messages than there were signs. Nevertheless, there were five major groupings that emerged naturally to characterize these messages: Services, Food, Stores, Entertainment, and Security, as seen in Table 4 below.

Table 4 Signs by Category

| Services | 52 | 67.53% |

|---|---|---|

| Taxes | 6 | |

| Financial | 6 | |

| Translation | 5 | |

| Cell Phone | 5 | |

| Immigration | 5 | |

| Copies | 4 | |

| Notary | 4 | |

| Legal | 3 | |

| Passport | 3 | |

| Shipping | 3 | |

| Transportation | 2 | |

| Rental | 2 | |

| Car Registration | 2 | |

| Religious | 1 | |

| Computer/Other Tech | 1 | |

| Food | 13 | 16.88% |

| Restaurant | 6 | |

| Grocery | 6 | |

| Charity | 1 | |

| Stores | 8 | 10.39% |

| Beauty | 3 | |

| Jewelry | 2 | |

| General | 2 | |

| Clothing | 1 | |

| Entertainment | 3 | 3.89% |

| Film | 1 | |

| Music | 1 | |

| Sports | 1 | |

| Security | 1 | 1.29% |

These are listed in order of their frequency, and below each header are the corresponding subgroupings. For instance, the “food” category contains messages related to restaurants, grocers, and provisions from charitable organizations, including a local church. As only the exterior signs themselves were used in this categorization, this does not negate the possibility that businesses could also offer services that are not explicitly mentioned, i.e. a grocery store could offer photocopies or cell phones even if not advertised, but the messages from such a company were encoded strictly on the basis of that which was readily observable from the outside, thus constituting the landscape.

FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

As previously described, whenever immigrant groups have settled into a new host society, their integration has depended on shared assumptions within the community (cf. Blommaert, 2010, p. 26). The Latino community in the United States is an example of what has been described as representing the “new assimilation” model of migration (Alba & Nee, 2003), where the integration of immigrants into their new host community is linked to other globalization functions, as well as the processes of migration, mobility, and power relations closely linked to the initial sociocultural and economic characteristics of migrant groups. Moreover, when immigrant communities are able to remain in close contact with their countries of origin, which is the case in Hazleton, their markers of identity are strong and usually highlighted, i.e. neither hidden nor diminished, as Mar-Molinero (2006) writes: “Despite being a minority, and often marginalized, community, one of its most identity markers, the Spanish language, is increasingly emerging as a potent and serious force, affecting policies and economic and cultural decision-making within mainstream US society” (p. 23).

The findings of our data confirm this assertion: When the city government made the decision to legislate English as the official and singular language of Hazleton, the Spanish-language presence in public spaces acquired special significance. The signs documented here do not follow a top-down policy established by a higher authority, but rather a bottom-up policy generated by and for members of the community (cf. Johnson, 2013, p. 10). As a result, the analysis of these signs also allows us to visualize other identity markers of the Latino community in Hazleton, including their needs, likes, and origins. In fact, signs from local businesses mostly reflect the Latino community’s needs, which primarily relate to their settlement and acclimation to life in the United States, including their accompanying immigration status.

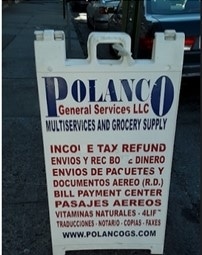

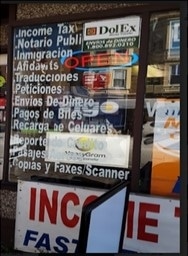

The services provided by these businesses recognize the physical presence of Latinos in the community and their concomitant economic value, as in Figure 2. For instance, observable in Figure 3 are the names of international companies, such as DolEx and Money Gram, two of the largest providers of international money transfers. While the latter is relatively well known, the former primarily serves the Latin American world and, according to their own self-presentation, “provid[es[ essential financial services to the underserved and underbanked US Hispanic Market.” In considering language usage in these signs specifically, we first noticed the mixing of English and Spanish, including the use of concordances like pago de billes. The term billes (cf. billete) is employed particularly by heritage speakers of Spanish in the United States. On the other hand, certain lexical items found do not conform to standardized orthography, including registracion (cf. registración) and inmigracion (cf. inmigración). Additional examples of code mixing are found in the uninhibited inclusion of multi-word concordances, such as Bill Payment Center and Multiservices and Grocery Supply.

Additional signs from local businesses were especially effective at establishing the national origins of speakers, i.e. by virtue of their usage, particular lexical items indexed speakers as coming from Cuba, Mexico, or the Dominican Republic. For instance, although the term viandas is used throughout the Spanish-speaking world to refer to various types of vegetables or meat, or even to the instruments used to transport prepared food (e.g. a lunch tray or bagged lunch), it is used distinctly in Cuba to indicate starchy roots, including yucca and sweet potatoes, which is reinforced by the image next to which this term appears (in Figure 4). Similarly, Alberto’s Mexican Produce (in Figure 5) clearly reinforces the connection to Mexico not only textually, but also visually through its reproduction of the national flag on the awning at the entrance.

The Dominican Republic is referenced with even greater precision not only through explicit phrases like Productos Dominicanos, but also on signs that identify particular dishes and beverages in restaurants, e.g. patica de cerdo, sopa de pata de vaca, and mori[r]-soñando as in Figure 6. However, one particularly salient example is found in Figure 7 below. The viewer is provided a glimpse into the cultural values of the people as reflected in the use of the term derrisados (> desrizado > rizado) to refer to a (perceptual) qualitative improvement in one’s hair from curly to straight, which differs from the terms rizado, alisado, or liso, which would refer simply to the act of straightening one’s hair. Furthermore, our data also indicate a diachronic change in the linguistic landscape of the neighborhood. Although previously owned by a woman named Diana, the business is presumably now owned by a woman named Luisa. Excluding the pre-existing portion of the sign, the remainder occurs solely in Spanish, which leads the viewer to believe not only that the new business owner is Latino, but also demonstrates the participation of the Latino community in the local economy of the city, which represents a potential desire to settle and stay in their new home despite the fact that their use of Spanish marks their separation from others living in the city.

Moreover, temporary posters also serve as documentation of the community’s likes, preferences, and interests. Displayed on the windows and/or doors of local businesses, these signs indicate the identity of the owner and also demonstrate the presence of Latinos in the larger community. For instance, Figure 8 contains three different posters that were also found individually on other businesses. The first poster references a four-day religious convention to be held within the city limits and is sponsored by a church with connections to other locations, including Wilkes Barre, PA, a city thirty minutes from Hazleton; Elizabeth, NJ, a city approximately thirty minutes from New York City; and Florida (Valle del Cauca), a municipality in southwestern Colombia. In addition to hosting local events for spiritual engagement, residents are also encouraged to connect electronically for virtual radio and sermons, oftentimes provided bilingually for the benefit of heritage and native speakers.

Additionally, the two remaining posters advertise (then) upcoming performances at a local club where Spanish-speaking musicians and singers frequently perform. The first singer, El Nene la Amenazzy, is a singer from Santiago de los Caballeros, Dominican Republic, and the second singer, Rubby Perez, is from Haina, Dominican Republic. Both are relatively well known in the Latin world, and the former has also collaborated with some other high-profile singers. Their music belongs primarily to the genres of reggaeton, bachata, and merengue; while the first is widespread throughout Latin America, the last two are clear indicators of Dominican identity. Consequently, it is significant that one can find advertisements promoting such events within Hazleton itself, as opposed to those in substantially larger nearby cities; as such, this demonstrates a willingness to embrace their own identity in the city-not at the expense of others, but for the preservation of their own culture and language.

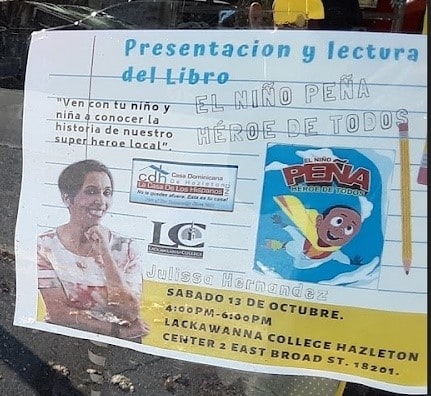

There are, however, other temporary signs that serve as valuable indexers of identity. For instance, Figure 9 below corresponds to a literacy event for children that is sponsored by the nearby Lackawanna College and offered by a private institution called Casa Dominicana de Hazleton. Not only does the existence of such an event invoke recognition of strong communal ties, but also an understanding that intergenerational transmission has not been interrupted, an important point to keep in mind. Nonetheless, much as the name implies, the primary goal of this organization is to promote Dominican identity within the city, and this is especially evident through the sense of inclusion and familiarity (through the use of tu) established in the accompanying slogan: “No te quedes afuera. Esta es tu casa.” = “Don’t stay outside. This is your home.”

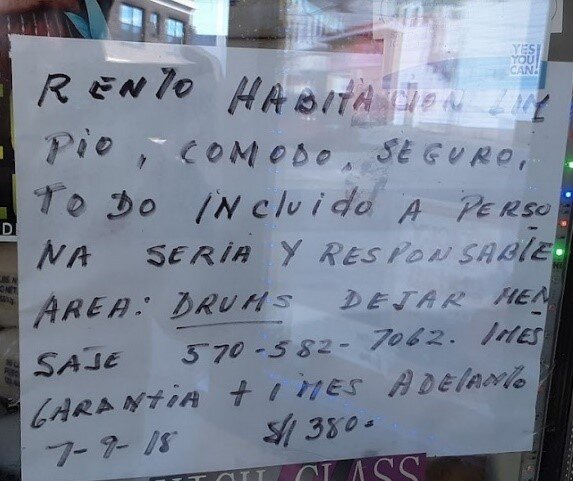

In another example, Figure 10 contains a personal message written in Spanish in which the property owner is looking for a new tenant for a clean, safe apartment with all utilities included. In addition to offering an extremely affordable price, the owner’s linguistic decision to write in Spanish also reflects a preference for who the future tenant will be, presumably someone who will also speak Spanish and who can relate to people from the Latino community. Most interesting, however, is the style of writing: Although the individual who wrote this message was not restricted by the norms of formal writing, it is clear that s/he is fully fluent in Spanish, as orthographic word-breaks are implemented at syllabic boundaries, e.g. lim-pio and perso-na.

Finally, despite the decision to legislate English as the official and singular language of Hazleton, Figure 11 below presents a government-issued sign in both English and Spanish, which at the very least demonstrates acknowledgment and recognition of the presence of more than one language as important in the community. It should be noted, however, that this was the singular official sign in the city that was present in both languages. For instance, other signs indicating parking regulations were available solely in English. Nonetheless, due to the official nature of this sign, one will also recognize that standardized rules of orthography have been followed for the Spanish message in a way previously unseen in most of the other signs.

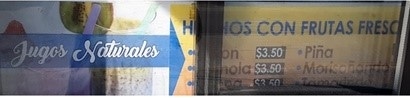

The presence of this governmental sign, as well as global brand names and slogans, indicates connections on a local, regional, and global scale. Furthermore, the Spanish signs examined here are examples of what Scollon and Scollon-Wong (2003) term “sociocultural association” and “geopolitical location.” That is, language usage on signs in the public space may index both the place where they (the signs) are located and also the presence of another sociocultural and linguistic group in that same location. Thus, the use of Spanish in Hazleton does not only index the presence of a Latino community in the city, but it also links their location to other parts of the world, e.g. locally through concert posters, regionally through transportation and communication services, globally through brand names, and more broadly culturally and linguistically through the invocation of specific lexical items. For instance, while collocations like jugos naturales target speakers of a particular language, others like empanadas de pollo invite not only speakers of a particular language but also those belong to a much larger regional area; similarly, lexical items like derrisado invoke the cultural and linguistic presence of a particular subset of the Latino community. As such, these words represent a sociocultural association that symbolizes that an aspect of the product or business is not related inherently to the place where that sign is located (cf. Scollon & Scollon-Wong, 2003), but rather to the origin of those whose patronage sustains that business. Furthermore, these words serve as geopolitical locations that are also reflective of one’s linguistic choices and origins.

Finally, we return to the impetus for this study in the first place: Regarding the notion that the increasing presence of Spanish perpetuates the “Latino Threat Narrative” (Chavez, 2013) among non-Latinos, our examination provides some insights. One could argue that, despite the broader irrationality of fear, residents of Hazleton feel as if they are being legitimately replaced (see Table 2 above). The demographic shift, which is actually driven by a combination of historical, economically driven ‘white flight’ and a contemporaneous increase in immigration to the city, could fuel more generalized anxiety or opposition toward Latinos. In addition, while industrialization provided an economic boon to Hazleton, it never truly recovered from the collapse of the anthracite industry and instead had to create new industries and expand the service sector, whose employees are predominantly Latino. Consequently, an incoming immigrant group that is neither ethnically nor linguistically similar to the existing residents provides an apparent scapegoat to blame for a continually declining economy-and, for an economy that is attempting to recover, a scapegoat for the perceived lack of new jobs for residents whose multigenerational families have remained in the city.

Furthermore, another particularly salient change even within the Latino community’s ability to communicate is worth acknowledging: The singular Spanish-language newspaper of Hazleton ceased to be published almost one decade ago. According to Amilcar Arroyo, the previous editor, Latino-run businesses frequently barely make ends meet, and, if they do manage to make a profit, oftentimes do not continue to invest in the newspaper beyond one advertisement per month or year. On the other hand, Elaine Maddon Curry, the founder of a local parent advocacy group, argued that the cessation of this publication was regretful for the community, as it “served as a bridge” between monolingual Spanish speakers and their community. As such, this could also represent the change and emergence of new local language practices (Pennycook, 2010), both within the Latino community and also between those who speak Spanish and/or another language, viz. English.

CONCLUSION

The present study has resulted in the recording, transcription, and categorization of every Spanish-language sign in Hazleton, Pennsylvania, in particular from the locally perceived core of Latino identity, i.e. the nearly two-mile long Wyoming Street. In undertaking this task, it has been determined that the resulting corpus of forty-one messages, which contains the entirety of messages in Spanish, is almost certainly directed at monolingual Spanish speakers as they confront the responsibilities of everyday life. As a result, each message from the signs in this corpus has been straightforwardly delineated into one of five thematic categories (Services, Food, Stores, Entertainment, Security). Furthermore, although it was not strictly possible to demarcate the signs according to language, given sometimes extensive mixing and the added complexity of native and non-native translations, the language usage noted has been described on a case-by-case basis, particularly where it concerned the intention of a particular message.

Additionally, this examination of Spanish-language signs in Hazleton has demonstrated the usefulness of linguistic landscapes in understanding more generally the immigrant experience, as well as language usage on signs in an urban, economically changing environment. Through visible signs, we were able to identify different Latino (sub)communities in Hazleton, and it appears that the majority of these members come from the Dominican Republic, though others from Mexico and Cuba are also indexed. These signs also indicate the possible presence of both first- and second-generation heritage speakers (Hakimzadeh & D’Vera, 2007). Moreover, bilingual and mostly Spanish signs characterized interaction between native English speakers and native Spanish speakers, as these signs reflect how local language practices emerge in conjunction with language, space, and place (cf. Pennycook, 2010). To this end, we have witnessed the partial historico-economic transformation of downtown Hazleton and not simply the existence of the perceptual Other.

Nevertheless, while the objective of these signs might be apparent to those who speak Spanish, the seemingly innocuous nature of these messages seems not to have had a similar effect upon those in the local government. In fact, while a radical demographic shift has occurred during the last two decades in Hazleton, Pennsylvania, which has been recognized as providing an economic boon to the previously declining, former-anthracite city, the discourse surrounding the presence of Latinos strictly foregrounds the most negative qualities associated with the Latino Threat Narrative. Interestingly, the mere presence of signs in Spanish, whether non-native speakers understand the messages conveyed, serve to index the presence of the Other, i.e. the presence of Spanish reaffirms the presence of Latinos, and the presence of Latinos becomes problematic when one recalls the danger that they supposedly pose due to the perpetuation of the Latino Threat Narrative. As a result, one cannot find even a single sign on Wyoming St. that supports that narrative, viz. that Latinos are unable and unwilling to blend linguistically, ethnically, religiously, etc. into their new home; rather, posted menus contain images of empanadas and freshly squeezed juices that remind the viewer that there is another distinct, yet perceptually homogeneous ethnolinguistic group in the city, and that group is the one to which all of the negative characteristics of the city are attributed.

Still, there are a few areas where additional research could yield further insights. Despite the seemingly clear demarcation between the Latino and non-Latino communities evinced by legislation and the linguistic landscape, this is not a reflection of the inherent nature of the residents of Hazleton, Pennsylvania. In fact, qualitative interviews with residents of the city would clarify whether the beliefs of government officials are reflected more broadly among residents. Additionally, while the focus of the present study was to consider the manner in which Spanish is used in the city, in particular on Wyoming Street, one is tempted to consider further the broader historical and contemporaneous linguistic landscape in the city, e.g. in shedding light on the role of English in an increasingly bilingual city (cf. Hult, 2014). Moreover, additional in-depth studies of the linguistic landscapes, the perceptual in- and out-group value of Spanish (cf. Toribio, 2009), and the attitudinal stance of the local governments in the neighboring cities of Allentown and Reading could present a fuller characterization of Spanish language usage in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.