INTRODUCTION

For teacher education programs it is crucial to support students’ development of discipline-based literacies (Snow & Uccelli, 2009; Walker & An-e, 2013), which involves their gaining control of highly valued academic genres such as undergraduate dissertations (Hyland, 2009). In Colombia, since the issue of Decree 0272 (Ministerio de Educación Nacional [MEN], 1998), and more recently Decree 2450 (MEN, 2015), undergraduate EFL Teacher Education Programs (EFL TEP) have included the development of research skills in their core curriculum, and even require that EFL pre-service teachers write research proposals and final-year research reports during their one-year teaching practicum. In the last 20 years, a number of studies exploring EFL TEP in Colombian universities (Cárdenas, 2009; Cárdenas & Faustino, 2003; Cárdenas et al., 2005; Fandiño, 2011; Guerrero & Quintero, 2004; Macías, 2013; McNulty, 2010; McNulty & Usma, 2005) have pointed out not only the importance of this research component, but also the need to help EFL pre-service teachers develop academic writing skills together with their research skills. Cárdenas et al. (2005), for example, recognize students’ lack of writing skills as one of the major obstacles to effectively completing their research projects. Also, McNulty & Usma (2005), in evaluating students’ development of research skills prior to their teaching practicum, observe that key research skills such as designing research proposals and writing research reports are not usually addressed in course programs before the eighth semester.

To help EFL pre-service teachers develop academic writing skills throughout their EFL TEP, writing instructors have proposed a wide range of approaches: genre-based instruction (Chala & Chapetón, 2013; Correa & Domínguez, 2014; Correa & Echeverri, 2017; Escobar & Evans, 2014), contrastive rhetoric (Gómez, 2011), and others (Colmenares, 2013; Hernández & Díaz, 2015). Of all these studies, only Escobar and Evans (2014) focused specifically on helping EFL pre-service teachers write their research monographs. In their pedagogical implementation, in which they used mentor texts and the strategy of text coding, the authors aimed to raise student awareness of the function and structure of each section in their monographs (i.e., introduction, theoretical framework, research design, analysis and findings, and conclusions), and the specific language structures they would need to express themselves accurately and coherently.

However, greater efforts need to be made to guide and support EFL pre-service teachers in writing academic genres, including research proposals and undergraduate dissertations. For this to happen, Correa (2009) advocates for a more situated practice of academic writing instruction in which texts are viewed as genres pursuing different social purposes, addressing particular audiences, and responding to particular situations; and writing is viewed as a disciplined-based, goal-oriented, and context-driven activity. An approach to academic writing that aligns with this view is Systemic-Functional Linguistics (SFL) genre-based instruction. Examples of attempts to implement this approach in an EFL TEP in Colombia are provided by Correa and Domínguez (2014) and Correa and Echeverri (2017). Despite success in these attempts, this approach has yet to be employed to help pre-service teachers meet the challenges of writing an effective undergraduate dissertation.

Accordingly, this article presents the results of a study that aimed to explore the benefits of implementing an SFL genre-based approach to help a group of EFL pre-service teachers write the statement of the problem section of their research proposals. The specific research question that guided this study was: ‘What are the potential benefits of implementing an SFL genre-based approach to help a group of EFL pre-service teachers write the statement of the problem section of their research proposal?’ In the following sections, first the theoretical underpinnings that guided the design and implementation of the writing workshops are presented, as well as the individual tutoring sessions with students. The context, participants and the pedagogical implementation are then described. Finally, the findings are presented and discussed before the concluding remarks are made.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

SFL and Genres

A theory of language that has influenced genre-based approaches to literacy development, especially the Sidney School, is Halliday’s (1978) Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL). According to this theory, language is functional in that it is used to get things done in particular contexts; and it is also systemic as it constitutes a system of choices, rather than a set of rules, available for users to make meaning in such contexts (Carstens, 2009). To describe what language does and how it does it, SFL theorists take the text as their unit of analysis. A text, they claim, is a piece of language in use that always occurs in two contexts: the context of culture and the context of situation (Butt et al., 2000; Schulze, 2015). The former deals with the knowledge of the social purposes and schematic structures of texts, whereas the latter deals with the social activity and subject matter (field), the reader-writer relationships (tenor), and the means of communicating and how it is used (mode) (Butt et al., 2000; Schulze, 2015).

Correspondingly, genre-based approaches informed by SFL theories understand genres as staged, goal-oriented social processes (Martin, 2009). They are social practices because members of a particular culture engage in interactions to realize them; they are goal-oriented because they are designed to enable such members to get things done; and they are staged because they usually unfold through relatively predictable phases to accomplish their purposes (Derewianka, 1990/2004; Hyland, 2003; Martin, 2009). Hence, SFL genre-based scholars focus on distinguishing the different social purposes of texts (e.g., to describe what happened, to argue a case, to explain how to do something), describing how they unfold through several stages to achieve their purpose, as well as identifying their lexical, grammatical and textual resources, and how these vary according to purpose, situation and audience (Hyland, 2002). This exploration of text and its context of use helps students gain awareness of how specific discourse communities organize their disciplinary texts, and gain control of the lexicogrammatical choices that characterize their specialized writing.

Genres and Scaffolding: The Zone of Proximal Development

Genre-based approaches to literacy development draw mainly on Vygotskian social constructivist theory of learning, in which learners play an active role in the making of meanings and the building of knowledge as they interact with their teachers and peers (Carstens, 2009). To better understand learners’ literacy development, Vygotsky introduced the concept of Zone of Proximal Development, which can be described as the distance between what learners are able to do alone to solve problems, and what they are able to do with the collaboration or assistance of more capable peers (Gibbons, 2015). The temporary support provided by a more knowledgeable person to help learners accomplish challenging tasks independently and successfully, based on their learning potential rather than their current abilities, is known as scaffolding (Gibbons, 2015; Hammond & Gibbons, 2005; Hyland, 2007).

According to Hammond and Gibbons (2005), effective scaffolding occurs on two levels: the macro-level or designed-in scaffolding, and the micro-level or contingent/interactional scaffolding. At the macro-level, as Derewianka and Jones (2016) state, teachers make decisions about which learning outcomes will be pursued, which genres and meaning-making resources are the most relevant to teach, and which sample texts will be used to exemplify them. They also take into account students’ previous knowledge, experience, and needs in terms of genre and language to design and sequence tasks, as well as deciding which tasks will be developed individually, in pairs, in small groups, or as a whole class (Derewianka & Jones, 2016). Framed in the macro-level, the micro-level of scaffolding refers to the kind of support teachers provide as they spontaneously interact with students during classroom activities (Derewianka & Jones, 2016; Hammond & Gibbons, 2005).

In scaffolding writing, teacher support includes a wide range of activities such as direct instruction, modelling, and discussion of texts, which aim to systematically guide students to gain familiarity with academic genres, and gradually develop their ability to construct these genres independently and effectively (Gibbons, 2015; Hyland, 2007). SFL genre-based approaches have refined scaffolding into an elaborate methodology that informs teachers’ designing and sequencing of classroom activities to help students gain control of academic genres through a series of stages (Hyland, 2007). This powerful methodology is known as the teaching-learning cycle (Butt et al., 2000; Derewianka, 1990/2004; Gibbons, 2015; Hyland, 2007).

Writing and the Teaching and Learning Cycle

The teaching-learning cycle as proposed by SFL genre theorists consists of four linked stages (Butt et al., 2000; Derewianka, 1990/2004; Gibbons, 2015; Hyland, 2004): 1) context exploration, where students and the teacher collaboratively build up knowledge of the context features of texts such as purpose, audience, subject matter, participant roles, and means of communication; 2) explicit instruction, where students are introduced to model texts and their attention is drawn to the language features of those texts; 3) guided practice, where students participate in group writing with the teacher as guide, sharing information and ideas, making suggestions, and negotiating meanings; and 4) independent application, where students apply what they have learned to independently construct a text, engaging in writing drafts and editing, and consulting the teacher only when needed. This cycle has supported teachers to help school and university students develop language and literacy skills, especially writing, in different fields and disciplines (Derewianka & Jones, 2016).

Throughout the stages of the cycle, scaffolding takes place. Thus, according to Derewianka and Jones (2016), the role of the teacher consists of providing models of relevant genres, explicitly teaching their social purposes, structures, and most salient linguistic features; and enhancing students’ language use by jointly constructing texts until they gradually take responsibility for using language to build their own texts. Teachers also constantly observe and analyze students’ language use at each stage of the cycle to monitor their progress and be able to make adjustments, when necessary, to the planned classroom activities, the level of support that needs to be provided, and the conversations with individuals, small groups, or the whole class around genres and writing (Derewianka & Jones, 2016). In doing so, Hyland (2003) states that this methodological model offers students continual opportunities to better understand how language and context intertwine in a text, and how this relates to the writing process. Each stage of the cycle provides students with a variety of tasks such as reading, brainstorming, research, graphic organizers, color-coding, discussions, evaluation of model texts, planning, drafting, peer review, and conferencing that help draw their attention to different aspects of writing (Butt et al., 2000; Derewianka & Jones, 2016; Hyland, 2003).

Writing Arguments in Academic Contexts

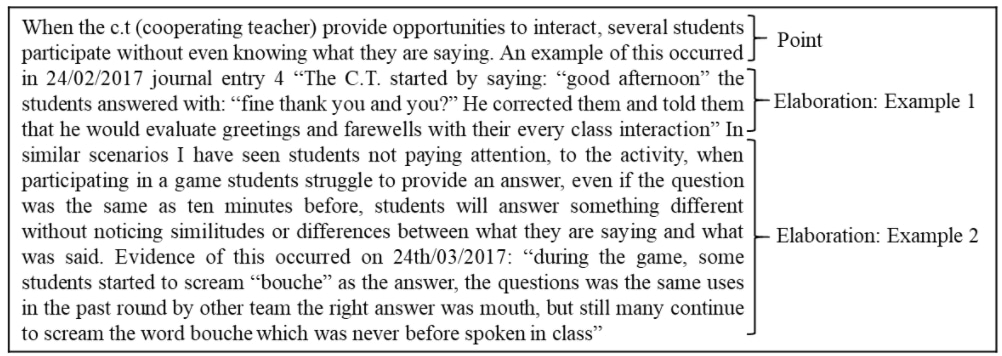

In disciplinary writing, students are expected to show familiarity with highly valued practices in their disciplines, such as “framing arguments in ways that their audience will find most convincing” (Hyland, 2009, p. 549). In fact, Andrews (2010) asserts that argumentation skills are an inherent aspect of subjects and disciplines so that teachers and students must be familiar with how arguments operate if they want to succeed in their specific subject or discipline. Among the different types of academic argumentation, thesis-driven writing is one most frequently assigned to students, in which they are expected to develop and support a central thesis or claim (Wolfe, 2011). This type of argument text, according to Derewianka (1990/2004), belongs to a group of texts called expository genres, which are concerned with the analysis, interpretation and evaluation of the world. The organization of argument texts focuses on an issue and the logically sequenced argument related to it, and unfolds in three main stages: thesis statement, argument(s), and reiteration of thesis (Derewianka, 1990/2004; Martin, 2009; Schleppegrell, 2004). The thesis statement stage may also include background information about the issue under consideration, and a preview of arguments that follow (Derewianka, 1990/2004). The argument(s) stage, in turn, unfolds in two phases, namely point (often more than one, and directly linked to the thesis statement and the other points) and elaboration (evidence and examples supporting each point) (Derewianka, 1990/2004; Martin, 2009). In the final stage, the thesis is restated, main points are summarized, and there is room for providing recommendations or calling for action (Derewianka, 1990/2004; Martin, 2009; Schleppegrell, 2004).

In university settings, genres across disciplines commonly include research proposals and undergraduate dissertations (Gardner & Nesi, 2012; Hyland, 2009). This kind of research writing implies elements of argumentation which help emphasize the significance of the information and project a balanced authorial self in the text, rather than merely presenting information (Davis & Shadle, 2000). For instance, research proposals, through which university students must demonstrate their ability to make a case for future action, usually include stating a purpose, describing a detailed plan, and displaying persuasive argumentation (Gardner & Nesi, 2012). Such university genres indeed conform to what Martin and Rose (2008) and Derewianka and Jones (2016) refer to as macro-genres, i.e., texts comprising elemental, shorter genres that work together to achieve the overall purpose and organization of the larger text. A research proposal, for example, is usually organized into several sections such as a description of the context, statement of the problem, a theoretical framework, a methodology, and expected results, each of which might be an elemental genre or embed several elemental genres such as procedures, recounts, explanations, and arguments.

Furthermore, in writing research proposals, university students need to introduce and write about a problem in a statement of the problem section where they must justify why the problem they claim they have identified should be researched. The statement of the problem section usually includes aspects such as the topic, the research problem, a justification of the importance of the problem, the gaps in our existing knowledge about the problem, and the audience who will benefit from studying such a problem (Creswell, 2012). In the field of education, according to Creswell (2012), a research problem might often be an issue, concern, or controversy that the researcher identifies in schools (i.e., practical research problem) and wants to explore further, or a gap in the existing literature (i.e., research-based research problem). To explain why it is important to investigate such issues, the researcher should provide several reasons and draw evidence from different sources, including what other researchers have reported, the experiences others have had in educational workplaces, and his/her own personal experiences, for example, in solving classroom difficulties in action research studies (Creswell, 2012).

METHODOLOGY

The study reported here can be categorized as a qualitative study that aimed to explore the benefits of implementing an SFL genre-based approach to help a group of EFL pre-service teachers write the statement of the problem section of their research proposals. Considering Creswell’s (2007) prevailing characteristics of qualitative research, we approached this study from an interpretive inquiry perspective, collecting data in the participants’ natural university setting, counting on multiple data sources, collecting participants’ opinions about the implementation, and mainly conducting inductive data analysis. Nevertheless, we also took a deductive approach to data analysis to further examine the major themes that emerged from the inductive analysis (Patton, 2015).

Setting

The study was carried out in a five-year undergraduate EFL Teacher Education Program at a public university in Colombia. During the last two semesters of this program (students’ teaching practicum year), students must take five subjects: Practicum I and Integrative Seminar I in the ninth semester; and Practicum II, Integrative Seminar II and Thesis in the tenth semester. These seminars are guided by practicum and research advisors who usually have a maximum of four advisees. Specifically, the study was conducted in the Integrative Seminar I (a research seminar of two hours in class per week and six hours of independent study time), in which students must write a research proposal based on the continuous and systematic observations of English lessons at the school in which they are doing their teaching practicum, with the purpose of improving the teaching and learning processes of English. This research proposal is composed of the following sections: context description, statement of the problem, research question and objectives, theoretical framework, and action plan. To write their research proposal, students should follow the writing guidelines in a manual for the research proposal and report provided by the practicum coordination, as well as APA standards. The guidelines in the manual establish that the statement of the problem section should consist of the presentation and description of the problem, its origins, and the presentation of supporting evidence. According to the Integrative Seminar I syllabus, the statement of the problem section should be constructed mainly through the following research activities: students observe the classroom practices in schools, including teaching methodologies used by either their cooperating teacher or themselves; they write their observations and reflections in their research journal; they then identify, interpret and reflect on the teaching and learning problems based on their journal entries; and then analyze and discuss the factors affecting such problematic situations during their research seminars. In addition, to gain better insights into the problem, pre-service teachers may gather data from other sources such as school students, the cooperating teacher or their fellow classmates from the seminar.

Participants

Participants in this study were a group of five EFL pre-service-teachers, four women and one man, whose ages ranged from 22 to 27 years old, and who were enrolled in the research seminar of the ninth semester of their EFL Teacher Education Program. Concerning their writing preparation, they had previously taken four courses on written communication and one course on academic writing during their program. These students were purposefully selected to participate in this study as they were readily accessible (they were our practicum advisees during the implementation), conformed a conveniently small group of typical pre-service teachers (last-year practicum students with previous preparation in academic writing, and facing the challenge of writing research proposals), and were willing to participate.

Pedagogical Implementation

To help this group of EFL pre-service teachers write their research proposals, a series of writing workshops following an SFL genre-based approach was designed and implemented during the Integrative Seminar I course. As the students considered the sections of the statement of the problem and the theoretical framework to be the most demanding texts to write, three workshops for each of these sections were implemented. The workshops included reading, writing and conference activities, following the principles and stages of the teaching-learning cycle as proposed by Derewianka (1990/2004) and Butt et al. (2000): Context exploration, explicit instruction, guided practice, and independent application. Furthermore, considering that students usually turn to previously approved final research reports as models, the model texts used in the workshops consisted of the statement of the problem and theoretical framework sections in two final research reports retrieved from the university repository. These model texts were not meant for students to imitate, however, but to be examined in terms of their purpose, structure, and language.

In this article, the focus will be placed on the statement of the problem section. Hence, the activities and strategies implemented during the three workshops to help students write such a section are presented here in the following figures that we created specifically for this paper.

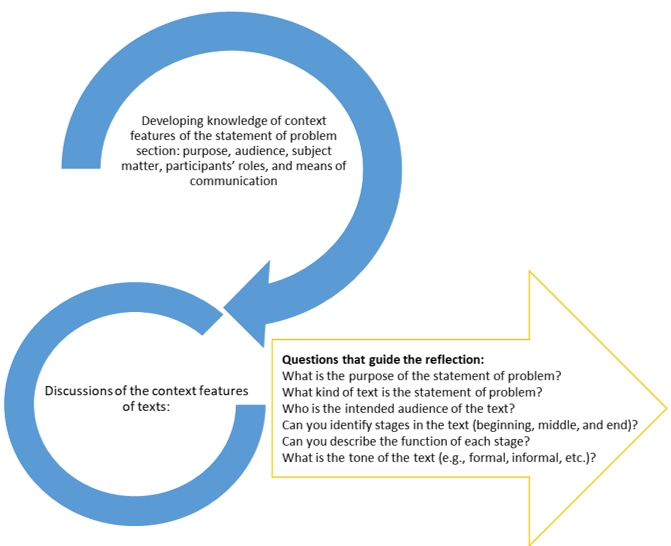

Context exploration: In this stage, students and the teacher collaboratively built up knowledge of the context features of the target text. The specific activities that we carried out in this stage can be seen in Figure 1.

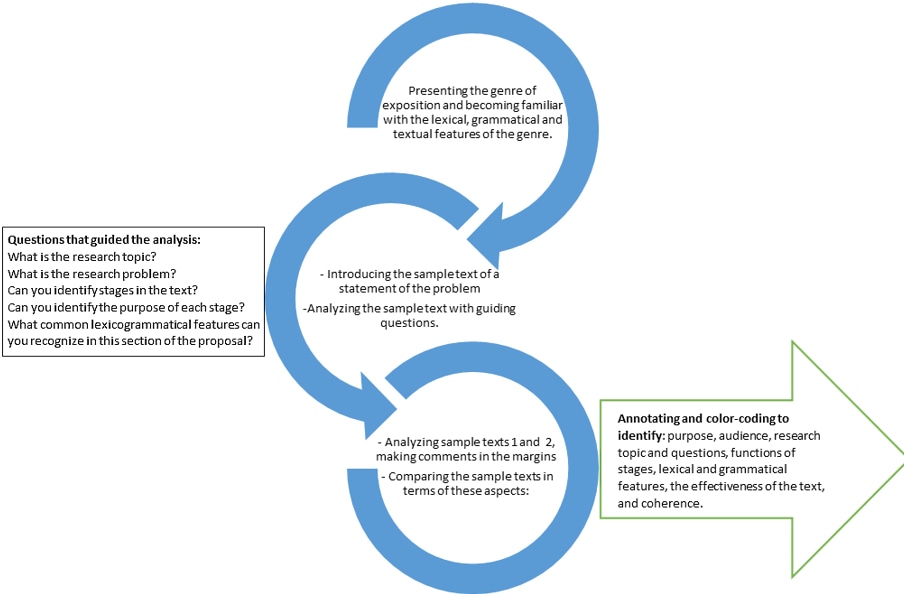

Explicit instruction: In this stage, students are introduced to model texts and their attention is drawn to the language features of those texts. The specific activities that we carried out in this stage can be seen in Figure 2.

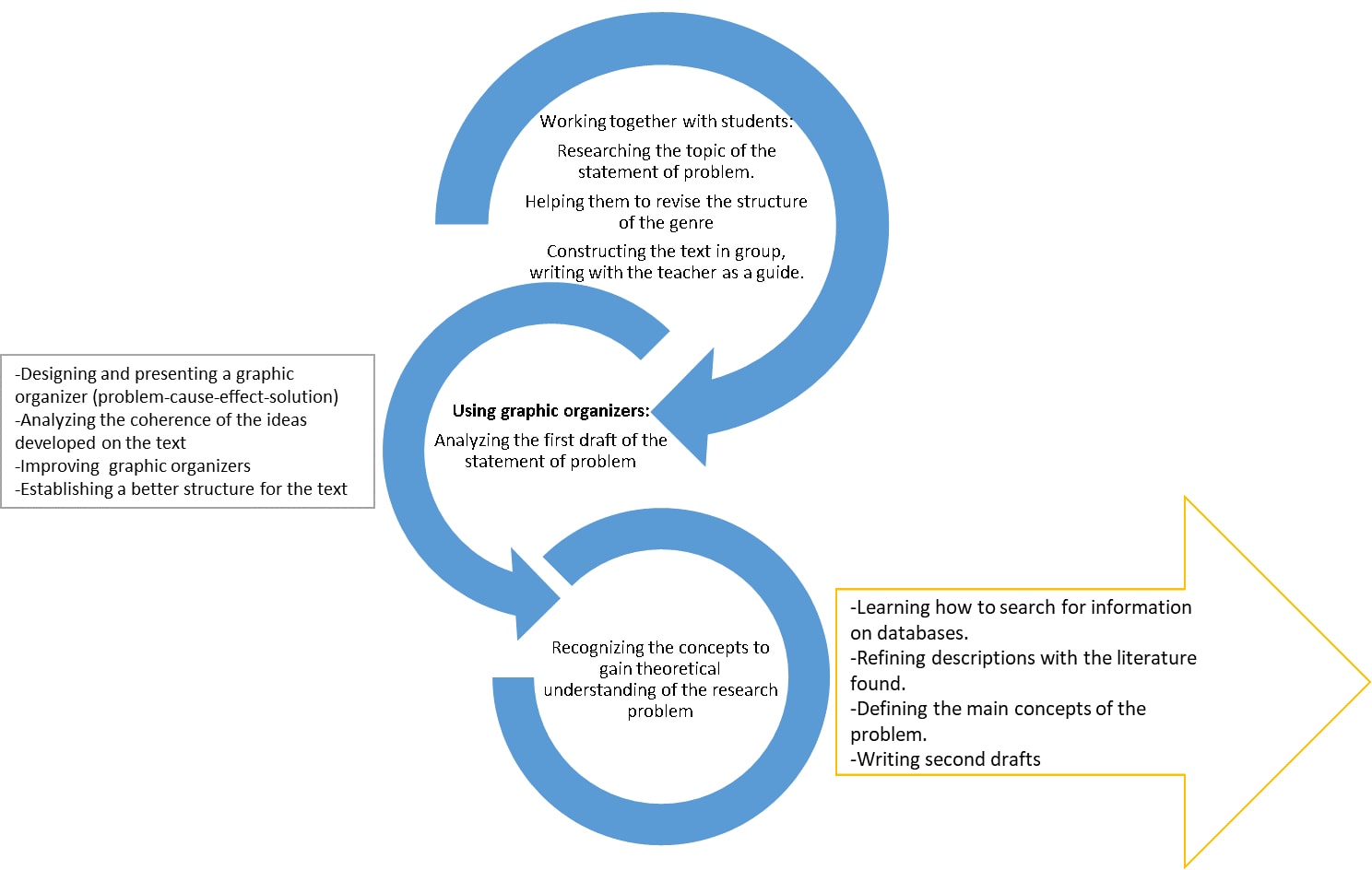

Guided practice: In this stage, students participate in group writing with the teacher as guide, sharing information and ideas, making suggestions, and negotiating meanings. The specific activities that we carried out in this stage can be seen in Figure 3.

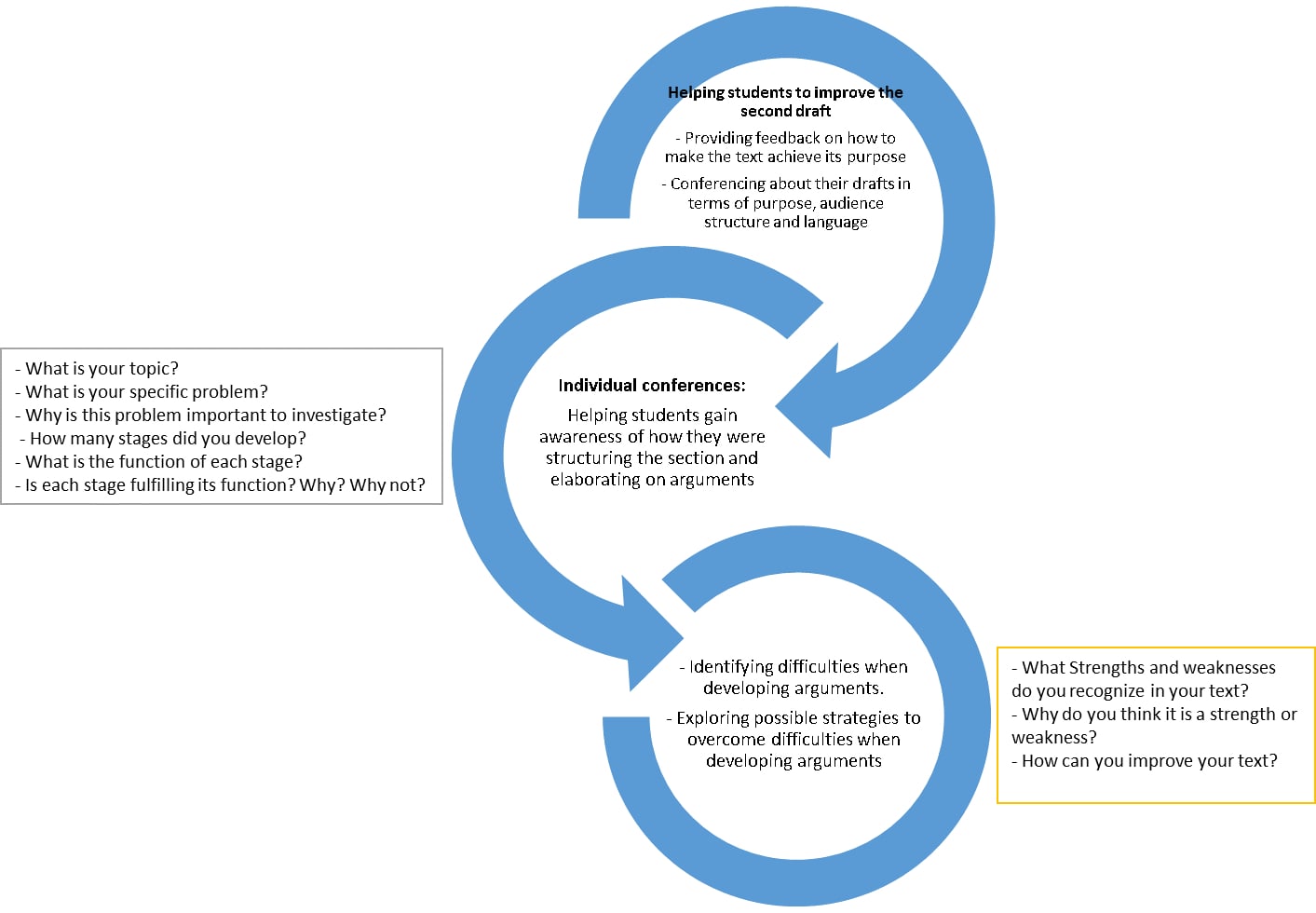

Independent application: In this stage, students apply what they have learned to independently construct a text, engaging in writing drafts and editing, consulting the teacher only when needed. The specific activities that we carried out in this stage can be seen in Figure 4.

Data Collection and Analysis

To gain better insights into the benefits of the pedagogical implementation described above, multiple instruments were used during the course of the study: samples of students’ work were collected as well as audio recordings made of the writing workshop sessions, individual tutoring sessions and individual interviews. Samples of students’ work consisted of the two drafts and the final text of the statement of the problem section that each student wrote. Audio recordings of the writing workshop sessions included recordings of the three sessions delivered to help students with their statement of the problem section. Audio recordings of individual tutoring sessions comprised recordings of the meetings with each student, held after the workshops, to discuss the second draft of their statement of the problem section. Audio recordings of individual interviews were of the semi-structured interviews held with each student after the submission of the final version of their statement of the problem section.

Data analysis was first carried out inductively, as the data were collected, and then deductively. For instance, samples of students’ work were first analyzed inductively as students submitted them (draft 1, before the workshops; draft 2, after the workshops; and the final text, after the individual tutoring sessions) to explore an ample range of possible issues in students’ writing and identify emerging themes which were organized into a chart. They were later analyzed deductively in terms of gains and challenges in structuring and developing arguments throughout their texts, one of the recurrent themes that emerged through the initial inductive analysis. Each student’s set of texts were then compared, creating a chart to see how they organized their statement of the problem section in terms of the three main stages of thesis statement, argument(s), and reiteration of thesis; and how they elaborated their arguments in terms of the two main phases of point and elaboration.

Similarly, audio recordings of the writing workshop sessions and individual tutoring sessions were initially analyzed inductively to identify emerging themes. Then, they were repeatedly analyzed to select and transcribe excerpts which show how students gained understanding of the way arguments were structured in the samples of the statement of the problem section discussed in class, and also how they gained awareness of organizing and developing their own arguments. Individual interviews were inductively analyzed to learn about students’ perceptions regarding the implementation, including how they valued the teaching strategies, the workshop activities, and the support they received during the writing process. Finally, excerpts from the interviews, which showed students’ perceived benefits from gaining awareness of how to structure their statement of the problem section, were selected and transcribed.

Ethical Considerations

Before carrying out the implementation proposed for this study, all participating students signed a consent form accepting the terms of the research project, and acknowledging the possibility of withdrawing at any time. To protect the identity of the participants, pseudonyms are used throughout this paper.

FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

This study aimed to explore the benefits of implementing an SFL genre-based approach to help a group of EFL pre-service teachers write the statement of the problem section of their research proposals. Overall, the data indicate that students gained a better understanding of how to structure the statement of the problem section, which helped them better define and develop ideas on the researchable problem they had identified during their classroom observations. The data also showed that they improved their ability to elaborate on the arguments they put forward to state their research problem. In what follows, we describe these two main gains.

Structuring arguments in the statement of the problem section

The data suggests that the implementation of the SFL genre-based writing workshops and individual tutoring sessions proposed in this study helped students gain an understanding of how to structure arguments in the statement of the problem section to justify their research problem. The analysis of students’ first drafts of their statement of the problem section as compared to their second and third drafts showed that students moved from merely describing the teacher’s actions, students’ disruptive behaviors and other circumstances they observed in the classroom, towards stating a researchable problem and providing arguments to justify it. Indeed, students’ final drafts showed that they noticeably organized their statement of the problem section into three main parts: introduction, body and conclusion. In the introduction, they stated the problem, provided background information and foreshadowed arguments. In the body, they developed each of the previewed arguments separately. Finally, in the conclusion, they restated the problem and put forward a statement of purpose.

For example, in her first draft, Karina described the three issues she had identified during her classroom observations (i.e., the kind of classroom interactions, the type of activities, and the lack of varied materials), as can be seen in the excerpt below:

First of all, the main kind of interaction present in the development of classes is teacher- students. The teacher is always explaining, dictating, writing on the board, asking questions to students in a few words, directing the class. There has not been space for student-student interaction as in peer or group work. The second issue I have observed is the kind of activities used in the class, there is always a practice or a workshop where students have to fill in the blanks, use isolated sentences and answer the teacher’s questions. Finally, there is not [sic] variation of materials. There are not many resources inside the classroom, but there are other spaces in the institution that could be used to develop the classes, a video room for example. The only resources present in all the classes observed are teacher, chalk board, students, notebooks or paper, a worksheet ones and pencil. (Karina’s Statement of the problem, Draft 1).

In this single paragraph, Karina compiles the three issues she identified as problematic in the EFL class, providing a brief description of each of them without further elaboration on why these issues are important to tackle and to conduct research into. In contrast, Karina’s final draft included an introduction in which she first explained in more detail the current importance of English teaching in Colombia and the challenge this poses to elementary public schools, then identified the decontextualized teaching methodologies as the problem, and finally pinpointed three potential causal factors: unvaried instructional materials, activities disconnected from themes, and limited classroom interactions. This can be seen in the following excerpt:

English teaching has recently become a very important issue for teachers, schools and even the national government which make big efforts to make of [sic] this process a meaningful and productive one. Despite all their efforts, it is evident that public schools, especially elementary schools, are not prepared to teach the language in the light of the latest approaches: methodology has barely changed. Although the institution is well known in the department for its educational processes, English in elementary levels is still taught artificially, that means, through decontextualized linguistics topics. There are several factors that prevent English education from having a context and a real purpose. For instance, materials are barely varied, activities have no connection to broader themes, and students’ interaction is completely reduced. (Karina’s Statement of the problem, Draft 3).

When compared to her previous drafts, Karina’s introduction in this third draft shows an increased awareness of how to structure the statement of the problem section by stating the problem and anticipating the arguments that follow. Rather than just describing the three observable classroom issues as she did in her first draft (barely varied materials, activities without connection to broader themes, and students’ reduced interaction), here she identifies such issues as the causal factors of the research problem. In this introductory paragraph, she also foreshadows the structure and content of the statement of the problem section as she later elaborates on these three main arguments, providing evidence from her journal. For example, the following excerpt shows Karina’s development of her second argument, that is, the disconnection between classroom activities and themes.

In the light of the latest theories of language and teaching approaches, the activities intended to be use [sic] in classes have evolved from a traditional grammar-based orientation to a more situated, contextualized and purposeful view. This implies the design and use of activities with a clear purpose and an audience, and a coherent relation between the language and a context. In addition, activities aim towards the integration of language practices and competences. However, the activities implemented in these classes were usually decontextualized and based on grammar notions. Some of the most common were: filling in the blanks exercises, answering questions, and writing simple sentences. These types of activities were reduced to completing grammar exercises or reinforcing grammar patterns; they were not enriched by a theme or content that contextualized language. The following journal excerpts illustrate how the traditional grammar orientation was evident in the class activities. “Vocabulary is very important so students can use more complete sentences, but is there another way to teach it different to giving a list?” (Journal, March 15th). (Karina’s Statement of the problem, Draft 3)

In this paragraph, Karina develops the second potential causal factor for the problem she identified, which she had previously anticipated in the introduction as she also did with the other two arguments. In addition, although she failed to overtly restate the problem, Karina concluded her statement of the problem section with a statement of purpose. The following excerpt shows how she concluded stating the purpose of her project.

In summary, the main purpose of this research project is to reconsider the way we are teaching in public schools, and venture to offer a more contextualized education supported by the coherence and organization of a theme-based syllabus that favors students’ interaction as well as the use of more challenging materials. (Karina’s Statement of the problem, Draft 3).

In her concluding paragraph, Karina proposes a possible solution to the problem she identified in the classroom, addressing the three causal factors she argued throughout her statement of the problem section.

During the interviews, students also acknowledged that gaining awareness of how to structure texts helped them write more effectively. When asked about the benefits of having participated in the writing workshops, for example, Kevin highlighted the importance of considering the purpose and structure of texts, and how this helped him improve his writing skills.

It helped me improve my writing because I’m usually very informal when speaking and writing. That needed to be changed and improved. The text structure is something one does not usually consider. And in every writing activity we did, we had to consider the structure. We had a clear goal, a clear conclusion, and a clear body as well. (Interview with Kevin, August 17, 2017).

In this excerpt, Kevin recognizes that, by paying heed to purpose and structure as they did during the writing workshops, he was able to write more formally, that is, organizing a text into different parts to achieve a specific goal. When discussing the purpose of the statement of the problem section, during an individual conference with Kevin, he said that it was to “justify why I consider the problem a problem” (Individual Tutoring Session, Kevin, April 25, 2017). In fact, he achieved this purpose in his third draft in which he finally identified the problem as a lack of significant learning in the classroom, and developed three arguments: students’ lack of understanding of what they say in English, a mismatch between teacher’s goal and students’ attitudes, and class time issues.

One of the activities proposed in the writing workshops that students recognized as particularly helpful in raising awareness of how to structure the statement of the problem section was the analysis of model texts. Karina expressed this in the interview.

As we have seen samples and analyzed other articles, checking what is correct and what is not, then we have gained more awareness of how to write those documents. Above all, since it is academic writing, not something personal, we start to recognize a format, and also the purpose and the audience. Then, we begin gaining more awareness, so the writing process becomes a bit easier. (Interview with Karina, August 17, 2017).

As Karina highlighted in this excerpt, discussing the purpose and structure of model texts helped her write academically and more effectively, even when the sample texts analyzed during the workshop sessions did not comply entirely with the expected structure. Kelly also recognized that it was helpful to identify the different stages (parts) in which a model text unfolds, and evaluate their effectiveness.

It was a useful exercise to analyze a work (the statement of the problem section), revise it, and notice the parts this work is made of, and how these parts are probably not so well structured. (Interview with Kelly, August 17, 2017).

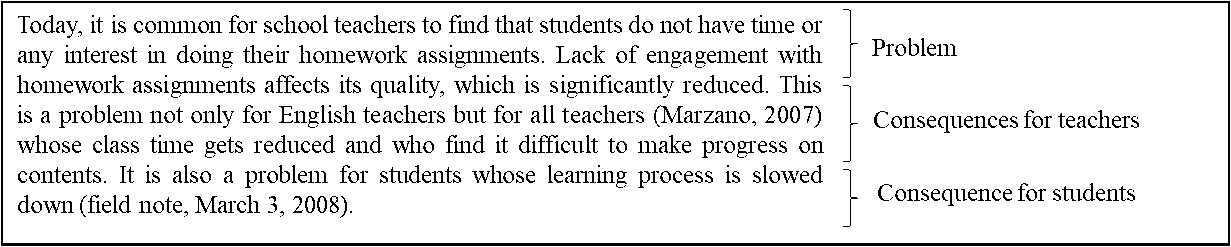

This was also noticed during the workshop sessions when examining the functions of the stages in a sample statement of the problem section students were asked to analyze. When discussing the introductory paragraph of such sample text, students were able to identify the stated problem and three consequences (Figure 5). For example, Karina said that the problem was “the quality of homework, but it’s caused because of the lack of engagement students have with it” (Workshop audio recordings, April 20, 2017). Students also identified that this introductory paragraph previewed at least three consequences of the problem: for teachers, the reduction of class time, and the difficulty to advance in the course content; and for students, the stagnation in their learning process.

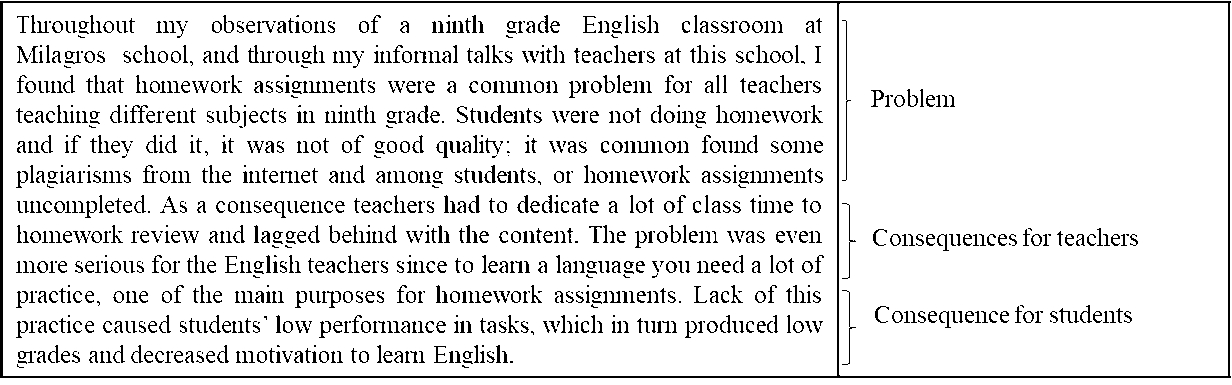

Although students considered this first paragraph as an effective introduction, since it states the problem and identifies consequences, they also noticed that the second paragraph failed to comply with the expected structure. For instance, when asked about what they expected to find in the second paragraph of the section (see Figure 6), Kyra said that the author would probably “give like the examples or the support of the first argument” (Workshop audio recordings, April 20, 2017), that is, the consequences for teachers. However, after reading and discussing this second paragraph, students noticed that, although the author seems to have developed such consequences, “at the end, in the last sentence, this person introduces the one for students” (Karina, Workshop audio recordings, April 20, 2017), referring to how students’ learning process is affected.

Moreover, students pointed out not only that the idea in the last sentence should have been elaborated on in another paragraph, but also that this second paragraph seems to paraphrase the first, as Kyra stated: “if we think (it) as a whole he did it again here but with other words” (Workshop audio recordings, April 20, 2017). The analysis and discussion of model texts during the writing workshops helped students focus on the function that each paragraph plays in the problem statement section and how these paragraphs are connected.

In summary, through the writing workshops and individual tutoring sessions, students gained a better understanding of how to structure arguments in the statement of the problem section they were expected to write for their research proposal. This helped them focus on clearly stating a researchable problem, and then elaborating on its justification through stages within the section.

Developing arguments further: thesis-support

The data also indicate that, through the implementation of the SFL genre-based workshops and individual tutoring sessions, students were able to justify the problem they stated in their statement of the problem section by putting forward and further elaborating on arguments. This gain could be seen in students’ drafts through which they showed progress in developing arguments by first stating a point and then providing evidence and information to support it. To exemplify this gain, we present the analysis of Kevin’s drafts as they are representative of what students were able to achieve in general.

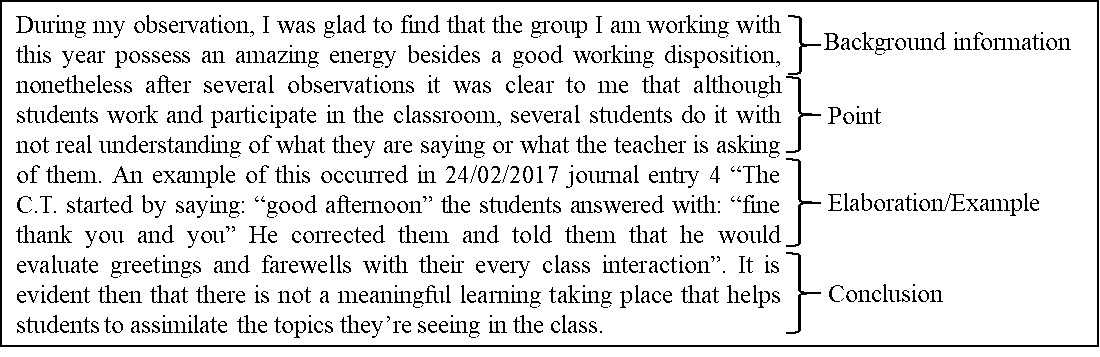

In his first draft, produced before the writing workshops, Kevin wrote a five-paragraph statement of the problem in which he contrasted the propitious conditions for learning English in the class, such as students’ readiness to participate and teacher’s resourcefulness, with students’ struggles to understand their teacher’s questions and their own answers, their lack of concern for learning English, and other unfavorable circumstances, such as students’ limited class time and missed classes. However, Kevin’s first paragraph failed to comply with the expected structure of an introduction for the statement of the problem section, that is, stating a thesis and previewing the arguments he should later elaborate on to support them. Instead, he organized this introductory paragraph into background information, point, elaboration and conclusion (see Figure 7).

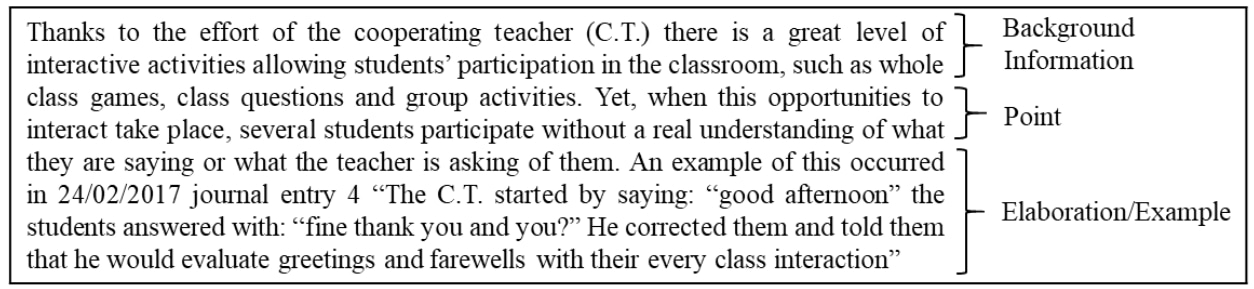

After the writing workshop sessions, which helped students gain awareness of the purpose and structure of the statement of the problem section, Kevin wrote a new introductory paragraph for his second draft, in which he kept the background information he had in his first draft, identified the lack of meaningful learning as the problem, and previewed three arguments to be developed in the section: students’ lack of understanding of what they say in English, the difference between the teacher’s and students’ goals, and class time issues. In addition, he developed the first of these arguments in the second paragraph of his second draft, reusing the point he had made in the introduction of his first draft, and the example he had used as evidence to support it. Kevin also added some background information before presenting his point in this first argument (see Figure 8). In doing this, he showed an improvement in the development of arguments.

In this paragraph, Kevin develops one of the reasons he identified as part of the problem, claiming that students participate in classroom interactions without actually understanding the use of English. To support this claim, Kevin described a classroom event he recorded in his journal. Furthermore, in his final draft, Kevin decided to remove the background information from this second paragraph as he noticed he had mentioned it in the introduction and there was no need to repeat it. Thus, he started directly stating the point (students’ lack of understanding of what they say in English) and then elaborated on it presenting two examples as evidence. This can be seen in Figure 9.

The analysis of Kevin’s drafts showed how he improved the development of arguments in his statement of the problem section, introducing changes that reflected a better understanding of the structure of an argument, that is, focusing on a point and bringing evidence to support it.

In summary, the scaffolding offered during the writing workshops and individual tutoring sessions helped students focus on supporting the claims they made in their statement of the problem section. As they focused their attention on stating clear points and providing supporting evidence, students gained a better understanding of how to put forward and elaborate on arguments accurately to justify the research problem they had stated.

CONCLUSIONS

The integration of a research component into undergraduate EFL Teacher Education Programs has led to a need to support EFL pre-service teachers’ academic writing development that enables them to write effective research proposals and final research reports. Despite the efforts made to meet this need, EFL pre-service teachers still face challenges in writing the most valued of discipline-based genres. Consequently, this article presents the results of a qualitative study that aimed to explore the benefits of implementing an SFL genre-based approach to help a group of EFL pre-service teachers write the statement of the problem section of their research proposals. In general, the findings in this study suggest that the approach used was indeed useful in enhancing students’ awareness of how to structure arguments in the statement of the problem section of their research proposals, as well as their ability to develop arguments more effectively.

In terms of structuring arguments in the statement of the problem section, students were able to state the problem, provide background information, and preview the arguments (introduction); develop each of the previewed arguments separately (body); and restate the problem and put forward a statement of purpose (conclusion). This was a significant gain since it showed that developing awareness of how to structure arguments helps undergraduate students who must write research proposals and dissertations move beyond the description of a researchable problem into its justification, as expected in a statement of the problem section (Creswell, 2012). Improving the ability to argue indeed prompts students to focus on the claims they want to make and support instead of just displaying information when writing research texts (Davis & Shadle, 2000). The development of such an ability, which is highly valued across disciplines, is then relevant and beneficial for students’ success in academic contexts where they are required to write genres such as research proposals and undergraduate dissertations (Andrews, 2010; Hyland, 2009; Wolfe, 2011). This is the case for most EFL Teacher Education Programs in Colombia, where EFL pre-service teachers are required to write research proposals and final research reports during their one-year teaching practicum. If students are to succeed in complying with these academic demands, they must be able to develop awareness of the purpose, audience, and structure, as well as how to frame arguments in such texts.

With regard to developing arguments further to justify their research problem, students were able to elaborate on each argument presented by first stating a point and then providing evidence and information to support it. For the group of EFL pre-service teachers who participated in this study, this was a significant gain inasmuch as it showed that developing the ability to elaborate on arguments helps undergraduate students focus on presenting concrete evidence and examples to justify the judgments they might make about a particular issue, demonstrating an objective and authoritative stance as expected in academic contexts (Hyland, 2008; Schleppegrell, 2004). Most academic texts, such as research proposals and final-year project reports, may prove to be challenging for students since they must build arguments, synthesizing and summarizing ideas as the text unfolds (Schleppegrell, 2004). If students fail to do this in their texts, they are likely to appear illogical or poorly reasoned in making an argument rather than reasoned, concrete, and developed, the latter all highly valued characteristics of academic texts (Andrews, 2010; Schleppegrell, 2004). In Colombia, EFL pre-service teachers must also develop the skills of arguing and persuading throughout their program, mostly through the writing of texts such as essays, literature reviews, and research reports, as is the case with undergraduate students in other parts of the world (Hyland, 2009; Snow & Uccelli, 2009).

Limitations of the Study

Despite the benefits of implementing an SFL genre-based approach to help a group of EFL pre-service teachers write the statement of the problem section of their research proposal as presented in this paper, the study has potential limitations. First, due to time constraints, it focused only on the statement of the problem section on students’ research proposals. Although equally important, other sections of the research proposal and final-year research report were out of the scope of this study. Secondly, the study also focused on students’ ability to structure and elaborate on arguments, without further exploring the lexicogrammatical features they used in their texts and examining to what extent they complied with the expectations of an academic register. Finally, the pedagogical implementation described here was carried out with a small group of highly proficient EFL pre-service teachers, a total of five, in the last year of their degree program, which is unlikely to be the case for other university instructors who may wish to implement something similar.

Suggestions for Further Research

More research studies are needed to explore how pedagogical implementations drawing on these approaches can further support EFL pre-service teachers’ academic writing development in our context. For instance, future studies could explore the usefulness of SFL genre-based approaches in helping students effectively tackle other sections of their research proposals and reports that might prove to be more challenging, such as the theoretical framework, findings, and discussion sections. These studies should thus examine the effectiveness of designing and implementing the teaching and learning cycle to help a larger number of students gain familiarity with and control of the genre and the register features of such texts, and evaluate its long-term effects. Furthermore, studies are needed to examine how SFL genre-based approaches can better equip writing instructors in EFL Teacher Education programs with the knowledge and abilities they need to provide more effective scaffolding.