INTRODUCTION

Although the belief that Latin America is used (or could be effectively used) more generally as a covert breeding ground for Muslim extremism has not been supported by any of the existing scholarship (see e.g. Ozkan, 2017; Zuñiga & Ozkan, 2020), this has not prevented academics and non-academics alike from perpetuating this imagined threat. For instance, in their discussion of the role and spread of Islam in Latin America, Sills and Baggett (2011) remarked quite casually-and arguably in a racist manner-that Arab Muslims can “pass for Latinos very easily” (p. 39). Moreover, they insisted that major newspapers in Quito, Ecuador, publish the faces of the al-Qa’ida members believed to be responsible for the acts of terror committed against the United States on September 11, 2001, and that Ecuadorians “scanning the pictures realized that these operatives could be any one of the people they saw everyday [sic] on the streets” (p. 39). Thus, because of the historical connection between Spaniards and Islam, Latin Americans are certainly not to blame for ‘accidentally’ confusing a Latino with a Muslim with a terrorist, right? Such fear-provoking stances serve as the exigence for the present study, which examines particular instances of textual injustice, inequity, and exclusion through social media before proposing a discourse- and content-based typology to characterize the distribution of such comments.

To this end, this paper is structured into six additional sections. Three of these undertake a literature review concerning respectively the presence of Muslims in Latin America broadly, the presence of Muslims in Ecuador specifically, and the defining traits of Islamophobia more generally. Next, the present study is introduced, including the research objectives, methodology, and corpus of data under investigation. Additionally, Spanish-language exemplars, which are accompanied by translations into English, illustrate the 10 most frequently employed discursive strategies to promote Islamophobic beliefs, and four strategies for solidarity-building with Muslims are also introduced. Finally, the last section offers some concluding remarks and areas for consideration for future research.

Muslims in Latin America: A Threat?

Moore and Mathewson (2013) report that Muslims currently constitute only one percent of the entire population of Latin America, totaling perhaps six or seven million, 60 to 70 percent of whom are non-Latino Muslims by birth. This would seem to indicate two important points: first, that the vast majority of Muslims in Latin America are either immigrants or descendants of immigrants who are non-Latino in origin; and second, that approximately 30 to 40 percent of Muslims in Latin America are reverts to Islam1.

Chitwood (2019) implies that this process of reversion is sometimes complicated, as it may require the dual construction of Islamic and Latin American identity (Islamidad and Latinidad). This would not seem to be problematic prima facie, but Ozkan (2017) notes that it is often quite difficult for Latino Muslims to reconcile two competing, substantively different value systems, viz. the traditional value system into which they are enculturated and the oft-romanticized Islamic societies that follow religious legislation (sharā’i’ al-islām) found in many communities and among many governments of the Middle East. Additionally, the interactions of Muslim reverts and non-Latino Muslims outside of the mandatory Friday prayers (Jumu’ah) are severely impeded due to such significant sociocultural differences, thus leading many to participate instead in online religious spaces. Thus, in addition to the substantial geographical distance, it is for this reason that extremist groups like Da’esh and al-Qa’ida have been unable to penetrate and/or radicalize Muslims in Latin America at the significantly higher rates witnessed in other nations (e.g. Tunisia). In fact, Ozkan (2017) states that Latin American Muslims constituted no more than 30 of the 6000 foreign fighters at the height of the expansion of Da’esh, while Benmelech and Klor (2016) found that the only Latin American nation to appear on the list of top 50 nations supplying foreign fighters was Brazil, in 45th place.

Consequently, although Muslim communities in Latin America would seem to be an incredibly insignificant threat with regard to possible acts of terror, Chitwood (2019) remarks through ethnographic fieldwork that social media can serve as a viable indicator of the kinds and degree of communication undertaken by and in opposition to Muslims, stating that: “Increasingly, those [Facebook] updates and notifications come from Latinx Muslims across the U.S., Latin America, and the Caribbean. They are debating their cultural identity, discussing Islamic law, protesting public policy, and greeting each other with peace” (pp. 83-84)2. As such, the 21st century offers an unprecedented opportunity to consider how religion and the media interact and build upon one another, particularly with reference to the construction of individual and collective religious identity.

Muslims in Ecuador: An Invasion?

The Republic of Ecuador, located in northwestern South America, emerged as a recognized independent nation in February 1840. As noted in Almeida (1996), Arabs-particularly those from Syria, Lebanon, and Palestine-have been a part of the socioeconomic and political fabric of the Ecuadorian nation since their arrival during the 19th century. These immigrants were generally referred to as ‘Los Turcos’ (The Turks). in large part due to their arrival from the erstwhile Ottoman Empire, and they generally arrived in search of employment opportunities that differed from the existing agricultural positions available in their home communities. To this end, many realized upon arrival that they could earn a living by selling their wares, often perceived at least initially as ‘exotic’ by those they encountered. Others found an audience in trading, inter alia, dates, rose water, and baklava (cf. Suquillo, 2002). However, it is important to note that local opposition to their presence was rooted primarily in their choice of profession and not in their religion, as the vast majority were Christian-or were they?

Taboada (2009) states not only that Muslims have been present in Latin America since the earliest colonial endeavors on the continent, but also that it is reductionist to subsume all of those arriving from the Middle East under the same national or religious borders for two compelling reasons. First, these nations simply did not exist at the time of the first waves of immigration. Second, Arabic-speaking Maronite Christians, Orthodox Christians, Jews, Muslims, and Druze all arrived simultaneously, as they had previously lived together even within the same neighborhoods. Furthermore, he notes that government records sometimes explicitly stated the arrival of Muslims during the late 19th and early 20th centuries in Argentina, Chile, and Brazil, among other locations in Latin America.

In the case of Ecuador, this began in Guayaquil in the early to mid-20th century (Jibaja, 2017). To determine precisely how many Muslims were originally or are currently present in Ecuador, however, has proven to be quite a difficult task, as the existing scholarship provides vastly different numbers, ranging from 1000 to 4000, up to 20000 (see Reichert, 1965; Delval, 1992; and Djinguiz, 1908, respectively). More recently, the Pew Research Center has estimated that less than one-tenth of one percent (0.011%) of the 17 million inhabitants of Ecuador are Muslim; thus, there would appear to be approximately 2000 Muslims in total in the predominantly Catholic country.

Nonetheless, the visibility of Muslims within Ecuador has changed considerably in recent years. For instance, there are now multiple masjid (places of worship) in the three largest urban centers of the nation, namely Quito, Guayaquil, and Cuenca. Additionally, Medrano (2015) notes anecdotally that, despite the fact that the Muslim community in the capital city of Quito is relatively unknown, it has attracted followers at a remarkable rate and has attempted during this expansion to share its culture, traditions, and language with followers and non-followers alike3, a fact supported by the present study. Additionally, there are few extant studies that consider Ecuadorian Muslims specifically. For instance, both Jibaja (2017) and Rodas Ziadé (2015) consider those who attended services at the Masjid Assalām in Quito-the former, through an ethnographic account of practices, beliefs, traditions, and conversion; the latter, through attempts to combat the analogization of Muslims with terrorists. To this end, Carrera (2017) describes the results more positively than the reader will see from the posts in the present study: “Confluences of identities work to shape Muslim identity in Quito, where the local and the foreign interact with and complement one another”4 (p. 24). This syncretism has resulted in the unique construction of Ecuadorian Muslim identity and is expanded in the work of Carrera (2017).

Islamophobia

At a compositional level, the term Islamophobia refers to a generalized fear of or anxiety toward Islam, which results minimally in an understanding of ‘difference’ or ‘division’ that distinguishes one group of people from another. The more accurate reality, however, is that this is typically expressed as an ideological positioning, sometimes but not always overt or explicit, against adherents of Islam and/or those believed to be from the so-called ‘Muslim World.’ As Said (1978/2003) notes in Orientalism:

European interest in Islam derived not from curiosity but from fear of a monotheistic, culturally and militarily formidable competitor to Christianity. The earliest European scholars of Islam, as numerous historians have shown, were medieval polemicists writing to ward off the threat of Muslim hordes and apostasy. In one way or another that combination of fear and hostility has persisted to the present day, both in scholarly and non-scholarly attention to an Islam which is viewed as belonging to a part of the world-the Orient-counterposed imaginatively, geographically, and historically against Europe and the West. (p. 344).

Although the concept only came to be recognized formally in the English-speaking world in the late 1990s, the Online Etymology Dictionary (n.d.) indicates that the related term Islamophobe was first attested in 1877 in English and 1914 in French. This certainly does not mean, however, that the concept itself is either recently discovered or newly experienced (cf. Awan & Zempi, 2020; Beydoun, 2018; Kundnani, 2014; Lean, 2017; Shyrock, 2010), as religious discourse and liturgical texts have clearly indicated a struggle between Muslims and non-Muslims since the earliest days of the revelation of the Qur’ān. However, it is important to recognize that the type of anti-Muslim rhetoric that exists today is considerably different in many ways from other varieties of xenophobic speech, particularly given the rise of such discourse in online environments.

Consequently, Kazi (2018) remarks that Islamophobia “isn't [simply] limited to acts of discrimination against women in headscarves or prejudice against Arabs (…) [, as] anti-Muslim slurs, taunts, and vandalism are the tip of a much larger iceberg” (pp. 6-7). In fact, Islamophobia is attested through publicized burnings of the Qur’ān, the production of overtly anti-Islamic films, and public protests against the establishment of Muslim places of worship (cf. Ernst, 2013). It can also be articulated more subtly through ingrained, underlying evaluative beliefs concerning Muslims, particularly if one characterizes over a billion people according to assumptions about “their misogyny, their opposition to modernity, their commitment to a sensual religion, and their association with specific races” (cf. Gottschalk & Greenberg, 2007, p. 84). It is for this reason that Martín and Grosfoguel (2012) suggest that Islamophobia is better understood “as a way to read what is happening, to express the present reality and to take note of its practices”5 (p. 169).

Nevertheless, the origin of such reactionary comments and behavior is also not limited strictly to one particular religious or political group, either, as reductionist narratives concerning Muslims are widespread and incredibly similar across these otherwise significantly different contexts. For instance, in the United States, a nation with which the Republic of Ecuador enjoys generally positive relations and whose media is widely consumed, Buchanan (2015) insisted that “Muslims are clearly more susceptible to the siren call of terrorism and more likely to be radicalized on the Internet and in mosques than are Christians at church or Jews at synagogue.” This might be expected from a conservative Christian commentator; however, similar sentiments have also been presented by liberal, politically-minded speakers (cf. Maher et al., 2014): “It’s the only religion that acts like the Mafia - that will fucking kill you if you say the wrong thing, draw the wrong picture, or write the wrong book.”6 Neither of these comments is uncommon, particularly as it concerns media representations of Muslims globally and, thus, the understanding-of a perhaps unknown or unfamiliar faith group-that the general public tends to adopt. In fact, as Kaufman (2015) indicates, “los odium dicta, por ejemplo los insultos raciales, raramente llegan por sorpresa: sus víctimas ya los han recibido en el pasado, sus generaciones precedentes también” (p. 83). Additional studies of the discursive construction of identity particularly those concerning Islam, are found in Akbarzadeh and Smith (2005), Alghamdi (2015), Martin and Phelan (2010), Mertens and De Smaele (2016), and Poole and Richardson (2006), among others.

METHODOLOGY AND CORPUS

The principal methodology used in this study is Critical Discourse Analysis (see e.g. van Dijk, 1993), which refers to an interdisciplinary, loosely organized set of thematic research interests in which a conscious attempt is made, as Chouliaraki and Fairclough (1999) state, to “mediat[e] between the social and the linguistic” (p. 16). Although there does not exist a single heuristic employed in this pursuit, there nevertheless remains the shared goal of investigating the relationships between and among the central issues of discourse, ideologies, power structures, dominance, and social (in)equality. To this end, because language usage functions as a tool for creating, reproducing, and reifying such sociocultural structures, the primary objective of CDA is to explicate from text and/or speech “what happens when language forms are played out in different social, political and cultural arenas” (Simpson and Mayr, 2010, p. 5).

In pursuit of this goal, there are three dimensions of content-based analysis undertaken here. First, the corpus under investigation comprises direct responses either to an initial post or another user’s comment. These responses are understood to be sociocognitive expressions that correspond directly to van Dijk’s (1998) ideological square, primarily as it concerns the linguistic-ideological positioning of ‘Us’ and ‘Them’ through the (de)emphasis of particular attributes or qualities. Second, particular attention is paid both to van Leeuwen’s (1996) sociolinguistic strategies used to represent social actors and to the primary objectives of critical discourse studies, as outlined in Bloor and Bloor (2007), viz. to analyze how discourse practices can reflect social problems; to increase awareness of how ideologies affect or are affected by injustice, prejudice, and misuse of power; and to investigate how meaning is contextually created and navigated. Finally, because no discourse is entirely free of ideology, it is understood here, following Fairclough (2003), that this corpus constitutes ‘social events’, which are directly related to social practices and social structures. Thus, these data are considered thematically both (a) as representative of underlying value systems found both in linguistic expressions and abstract thought, and (b) as reflective of particular ways of understanding and/or constituting one’s world through speech-and, in the case of the present study, “speech or other expressive conduct that is in some sense intimately connected with hatred of members of groups or classes of persons identified by certain ascriptive characteristics” (Brown, 2015, p. 4). Esquivel (2016) expresses a similar view.

The corpus for this study contains data extracted in July 20207 from the institutional Facebook page for La Comunidad Musulmana Ahmadia (‘The Ahmadi Muslim Community’). Python v3.7.2 was used to retrieve dates, comments, reactions, and shares for all posts over a two-year period. In particular, this resulted in over 600 posts, though the present study does not investigate the corpus in its entirety. Instead, the 10 posts with the greatest number of comments served as the representative sample, as they account for 57.19% of the total comments and 46.73% of the total reactions. Although every text-based post was also accompanied by an image, three posts presented either an image or video unaccompanied by a caption or written text. Because it cannot be determined with certainty why a given user ‘reacted’ or ‘shared’ a particular post, only the content of the comments is investigated here. For the readers’ consideration, Table 1 below contains the corresponding metadata for these ten posts.

Table 1 Corresponding Metadata for the Top Ten Posts

| 1. Post | 2. Date | 3. Text | 4. Image | 5. Video | 6. Comments | 7. Reactions | 8. Shares |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 20 Mar. 2019 | - | - | 16 | 11 | 2 | |

| 2 | 15 Feb. 2020 | - | ✓ | - | 22 | 75 | 0 |

| 3 | 25 Mar. 2018 | ✓ | ✓ | - | 39 | 306 | 19 |

| 4 | 30 Sep. 2019 | ✓ | ✓ | - | 100 | 479 | 23 |

| 5 | 4 Aug. 2019 | ✓ | ✓ | - | 63 | 295 | 56 |

| 6 | 3 Jul. 2019 | ✓ | ✓ | - | 80 | 69 | 7 |

| 7 | 9 Jan. 2019 | - | ✓ | - | 102 | 530 | 75 |

| 8 | 8 Oct. 2019 | ✓ | ✓ | - | 33 | 161 | 25 |

| 9 | 4 Sep. 2018 | ✓ | ✓ | - | 123 | 276 | 34 |

| 10 | 17 Jan. 2019 | ✓ | ✓ | - | 32 | 300 | 22 |

| TOTAL: | 610 | 2502 | 263 | ||||

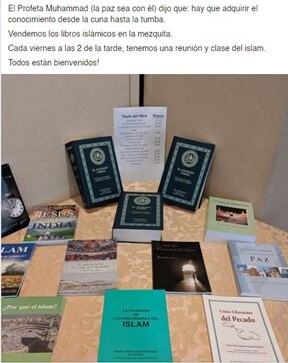

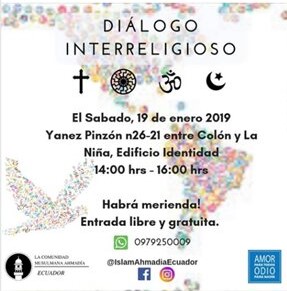

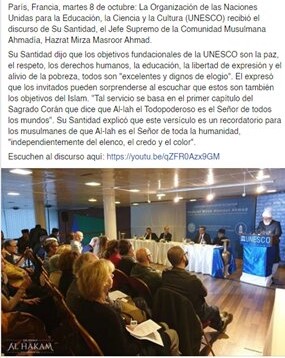

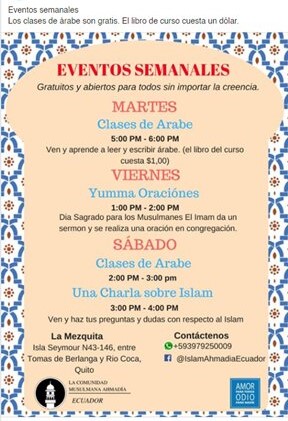

Thematically, all 10 posts are similar to one another in that they attempt to (re-)affirm positive self-presentation primarily through the distribution of knowledge and the building of a physical and online community. For instance, three of the posts describe a 12-week Arabic course for members of the immediate religious community and for members of the wider community, i.e. not simply limiting this opportunity to existing followers of Islam who might otherwise already be religiously motivated to acquire fluency in Arabic. On the other hand, four of the posts reference public gatherings that promote greater understanding, including a “Meet a Muslim” event, an interfaith religious event, a charitable event in and for the local community, and a “Coffee and Conversation” event. One post contains a video from NowThis Opinions, an online channel on YouTube, that aims to challenge negative perceptions of Muslims. Finally, the remaining two posts are intended principally for members of the Muslim community: One advertises a variety of religious books for sale, and the other contains a picture from a public lecture in France from the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jama’at, unsurprisingly the same religious denomination to which this particular mosque (masjid) belongs. All 10 of these most-commented on posts can be viewed in Appendix 1.

RESULTS

Discursive Strategies Employed in Comments

There are 10 recurring discursive strategies employed by respondents. As Fairclough (2003) reminds us, “language is an irreducible part of social life, dialectically interconnected with other elements of social life, so that social analysis and research always [have] to take into account language” (p. 2). It is for this reason that these discursive strategies are presented not only to identify the form and function of situated language usage, but also to identify how socioeconomic, racialized inequities in the ‘offline’ world are essentially reproduced in the ‘online’ world (cf. Boyd, 2014). As a result, one can reasonably assume that the characterization of Muslims in an online context by non-Muslims reifies beliefs and divisions that already exist in everyday life, though the author concedes that these tend to be much more explicit in the ‘online world’ than in the ‘offline world.’ Moreover, as Oboler (2013) suggests,

The aim is not only to spread the hateful content, but to also normalise it. When the hate speech becomes no more than another opinion, the hate itself can be openly expressed not only online, but also in daily life (p. 10).

It should be noted, however, that the Spanish comments below are presented exactly as they appeared in the original postings. As a result, any missing acute accents (e.g. pais instead of país, America instead of América, and satanicos instead of satánicos), misspellings (e.g. aki instead of aquí, enceñando instead of enseñando, and piedrasos instead of piedrazos), typographic errors (e.g. idlam instead of islam), fused sentences, etc. remain uncorrected. Similarly, while the translations offered are intended to remain as close as possible to the illocutionary force of the original, square brackets with some lexical or grammatical pointers are added where the English translation would otherwise sound less natural. Additionally, it is also necessary to understand that these discursive strategies are rarely used in isolation; instead, they are found in conjunction with one another within a single utterance. Consequently, although each is addressed and exemplified below, it must be recognized that many could also just as easily illustrate one or more of the other discursive strategies presented here.

First, there is the invocation of scripture from both the Bible and the Qur’ān8. The former arises when the response is intended to antagonize adherents of Islam9, and the latter is used when the moderators are harshly implored to provide an exegesis of the Qur’ān or a defense of Islamic beliefs. Although approximately 40 Qur’anic verses and approximately 60 Biblical verses were referenced, most of these were simply posted without any qualification, description, or explanation, as in (1a-b). Additionally, sometimes the verses were provided verbatim, and on other occasions were simply listed as in (1c).

(1) a. He aquí, JESÚS les salió al encuentro, diciendo: !Salve! Y ellas, acercándose, abrazaron sus pies, y le ADORARON

‘As they went to tell his disciples, behold, Jesus met them, saying, “Rejoice!” They came and took hold of his feet, and worshiped him. (Matthew 28:9)’

b. A quienes no creen les castigaré severamente en la vida de acá y en la otra. Y no tendrán quienes les auxilien.

‘And as for those who disbelieved, I will punish them with a severe punishment in this world and the Hereafter, and they will have no helpers. (al-Imran 3:56)’

c. 4:101, 4:144

On the other hand, there were instances where either text- or image-based references to specific verses were, indeed, qualified. For example, (2) does not contain the actual content of the verse but is provided in response to a conversation about Muhammad (pbuh). Moreover, while (3) initially appears polite due to the presence of a standard greeting, the reader realizes by the end of the comment that it is ultimately antagonistic. Three bilingual images are provided (English/Arabic) with three separate verses circled, which the poster would like the moderator or another Muslim to justify. In this case alone, the verses are reproduced below. Incidentally, all but one of the Qur’anic verses cited come from the Medinan suwar, which were revealed after Muhammad’s (pbuh) departure from Makkah and, thus, tend to be much more direct in their legislation of the rules of jurisprudence (fiqh) and legislation (sharā’i’ al-islām). Nonetheless, a comprehensive list of all verses cited can be consulted in Appendix 2.

(2)Falso profeta vaticinado en Galatas 1 versículo 6

‘[This] false prophet [was] foretold in Galatians 1:6.’

Reference: ‘I marvel that ye are so quickly removing from him that called you in the grace of Christ unto a different gospel.’

(3)Buenas tardes. Tengo varias dudas sobre estos pasajes coranicos. Espero una respuesta objetiva, gracias, no como otros musulmanes que me han contestado “es invento de los judios sionistas”

‘Good afternoon. I have quite a few doubts about these Qur’anic verses. I’d like an objective response, thank you, [and] not like [those] of other Muslims who have [simply] told me that it’s an invention of the Jewish Zionists.’

Reference #1: ‘So when you meet those who disbelieve [in battle], strike [their] necks until, when you have inflicted slaughter upon them, then secure their bonds, and either [confer] favor afterwards or ransom [them] until the war lays down its burdens. That [is the command]. And if Allah had willed, He could have taken vengeance upon them [Himself], but [He ordered armed struggle] to test some of you by means of others. And those who are killed in the cause of Allah - never will He waste their deeds.’ (Muḥammad, 47:4)

Reference #2: ‘[Remember] when your Lord inspired to the angels, I am with you, so strengthen those who have believed. I will cast terror into the hearts of those who disbelieved, so strike [them] upon the necks and strike from them every fingertip.’ (al-Anfal 8:12)

Reference #3: ‘That [is yours], so taste it. And indeed for the disbelievers is the punishment of the Fire.’ (al-Anfal, 8:14)

Second, there is the construction of a narrative of ‘justifiable fear’. This rationalizes the trepidation of those who oppose the presence of Muslims and Islam in Ecuador on the basis of historical and/or contemporaneous acts of violence with which Muslims may have been involved or connected. Sometimes this arrives through general warnings for those who may be less familiar or completely unfamiliar with the faith (4a-d) and notably includes the use of the adverbial cuidado. In other instances, there are specific references made to the presupposed actions of Muslims within the country, viz. through radicalization, recruitment for extremist campaigns, and religiously-sanctioned murder (5a-f).

(4)a. Es una trampa … Cuidado

‘It’s a trap - [be] careful.’

b. Cuidado. Sabemos q quieren

‘[Be] careful. We know what they want.’

c. Cuidado que nada es gratis en la vida, a lo mejor terminan pagando con adoctrinamiento religioso

‘[Be] careful. Nothing is free in life. In the end [you] might end up paying through religious indoctrination.’

d. cuidado y no sea solo clases de baile sino lavado de cerebro

‘[Be] careful. It’s not going to be just dance classes, but brainwashing.’

(5)a. Nunca estuve de acuerdo que les permitan a ustedes radicarse en mi pais, ustedes con su fanatismo son sumamente peligrosos.

‘I never agreed with those [society/government/etc.] letting you reside in my country. You and your fanaticism are incredibly dangerous.’

b. Ya nos quieren musulmanizar

‘Now they want to Muslimize us.’

c. ¿Están reclutando yihadistas?

‘Are you recruiting Jihadists?’

d. Da miedo esa religion, el coran manda a matar a todos los infieles (o sea a todos los que no siguen el islam)

‘This religion is scary. The Qur’ān instructs them to kill all the non-believers (or, rather, those who do not follow Islam).’

f. Una pregunta: Qué nombre le pusieron al Califato Islámico fundado por ustedes en territorio ecuatoriano?

‘One question: What name did you give the Islamic Caliphate State you founded on Ecuadorian territory?’

Third, there is a metaphorical ‘call to arms’ against those who are ‘invading’ the country and/or corrupting society simply by proximity or a desire to coexist. In the case of the prosaic exemplar in (6a), a litany of characteristics is attributed to the presence of Muslims, including restrictions on clothing, the spread of violent behaviors, the growth of communities in which Muslims congregate, etc. The shorter comment in (6b), meanwhile, directly positions such ‘outsiders’ as inherently antithetical to the core values held by Ecuadorians.

(6)a. No queremos esa religion aki, no queremos mahoma, ni burka, extemistas ni terroristas ni personas enceñando como matar infieles ni caos ni barrios musulmanes donde los nativos no podemos entrar, no queremos la guerra ni la Sharia ni el multiculturalismo que incluya el islam como cultura y religion. Islam fuera de Ecuador no al terror no al medio [sic] NO AL ISLAM esto no es Europa, que han acabado con ella, esto es AMERICA tierre de cristianos, de protestantes de catolicos pero de cristianos. FUERA EL ISLAM DE ECUADOR

‘We don't want that religion here. We don't want Muhammad, the burqa, extremists, terrorists, people teaching how to kill non-believers, chaos, or Muslim neighborhoods where [Ecuadorian] natives cannot enter. We don't want the [violence], the Shari’ah, multiculturalism that includes Islamic culture and religion. Islam, get out of Ecuador! No to terror[ism]! No to fear! No to Islam! This isn't Europe that you’ve already [destroyed]. This is AMERICA, land of the Christians, of Protestants, of Catholics, but [nonetheless] of Christians. ISLAM, GET OUT OF ECUADOR!’

b. Su doctrina es fundamentada en el odio a los cristianos y judíos. Lamentable q ahora quieran manipular en Ecuador

‘This [religious] doctrine is based on the hatred of Christians and Jews. It’s sad that they now want to manipulate/control [us here] in Ecuador.’

c. hay que matarlos antes de que nos maten en nombre de ala

‘We need to kill them before they kill us in the name of Allah.’

d. En todos los países donde empiezan a crecer dan problemas, pues no buscan adaptarse a la sociedad donde viven queriendo imponer sus torcidas creencias, cuidado con dejamos engañar con una falsa religión de paz cuando en realidad sin adoradores de la muerte

‘In all of the countries where they start to grow, there are problems. Well, they don’t try to adapt to the [new] society where they live. They want to impose their twisted beliefs. [Be] careful not to be fooled by this fake religion of peace when they actually just worship death.’

e. vayan a su tierra a propagar sus herejias

‘Go [back] to your [own] country to spread your here[tical views].’

Fourth, there are general insults and sarcastic comments in response to original posts, to favorable comments from others, or to both. Comments like (7a) and (7b) are widespread and generally independent of the content of the original post. On the contrary, (7c-e) are all closely connected to the original post. For instance, (7c) is an attempt to build solidarity with another critic of Islam; (7d) is a response to a post advertising the sale of religious texts and makes reference to the aftermath of and public outcry against the publication of Salman Rushdie’s novel from the late 1980s; and (7e) is both an allusion to anti-Semitism and a response to a post sharing information about a freely-offered course on the Arabic language.

(7)a. VIVA EL DIABLO

‘Long live the Devil!’

b. Yo quiero ser terrorista

‘I want to be[come] a terrorist.’

c. exactamente, la basura es basura, llámese reggaeton, machismo o Islam

‘Exactly - trash is trash, whether it’s called reggaeton, machismo, or Islam.’

d. no venden el libro ‘los versos satanicos’ ??

‘They aren’t selling The Satanic Verses?’

e. Tal vez cursos de hebreo?

‘[And] what about courses on [the] Hebrew [language]?’

Fifth, there are directive speech acts toward both Muslim residents and non-Muslim defenders of the nation. While the majority simply encourage Muslims to leave Ecuador and “return to their homeland,” as in (8c-e), others are more direct. For example, (8a) argues that Muslims would be better suited to help women in Muslim-majority countries, (8b) urges Ecuadorians to follow in the footsteps of the commentator by calling the authorities immediately if they should happen to hear the Takbir. Finally, (8f) is by far the most extreme, hostile comment to any post and requires here no additional explication.

(8)a. mejor q hagan algo por las mujeres musulmanas en paquistan o e iran y no vengan con su falso dogma del idlam

‘It [would be] better if they did something for the Muslim women in Pakistan or Iran [instead of] coming here with their false dogma of Islam.’

b. Sin bombas....ni atentados terroristas... Por qué si escucho: Allahu Akbar llamo a la policía....!!

‘No bombs, no terrorist attacks. So, if I hear Allāhu akbar, I’m calling the police!’

c. No sé ni me interesa, toda esa gente debe largarse de nuestro pais

‘I don’t know and nor am I interested in this. All of these people need to get out of our country.’

d. Regresense a arabia

‘Go back to Arabia [the Middle East]!’

e. Fuera musulmanes de mi país!

‘Muslims, get out of my country!’

f. muéranse moros malditos, jodanse con el perro de su profeta

‘Go die, you bastard Moors. Fuck yourselves and that dog of a prophet [of yours]!’

It is worth recognizing that, although most of the directives were quite dire, others were more genuine. For instance, a short exchange evolved concerning whether it was truly necessary to sell religious texts as opposed to providing them for free, i.e. as an attempt to build interfaith bridges. As such, those in (9a-c) below did not indicate any general opposition to the presence and/or distribution of the texts.

(9)a. Hermanos, no se vende el Coran

‘Brothers, don’t sell the Qur’ān.’

b. ¿Por que no lo regalan?

‘Why don’t you give them away?’

c. Porque los venden? Porque no los imparten?

‘Why sell them? Why not hand them out?’

Sixth, there is the presence of formulaic constructions and false equivalencies. The former is recognized straightforwardly through expressions involving subject matter for courses and/or topics about which participants might want to learn, as in examples (10a-d). The latter involves, in most instances, either a direct comparison between Muslims and those who commit acts of violent retribution (11a) or terror (11b), or the conflation of an otherwise unknown religious denomination with religious fundamentalism (11b-c).

(10)a. Y la clase para lapidar, cuando?

‘And when [is] the class on stoning [people]?’

b. Y que dia dan clases para armar coches bomba manejo de explosivos y de recompensas por asesinar cristianos

‘And which day are the classes on making car bombs and giving rewards for killing Christians?’

c. Entender como poner la burca a mujeres

‘To understand how to put the burqa on women.’

d. Ahi es donde enseñan a azotar mujeres? Me interes[a]

‘Oh, is this where they teach [people] to whip women? I’m interested.’

(11)a. no todos musulmanes son terroristas, pero todos terroristas son musulmanes

‘Not all Muslims are terrorists, but all terrorists are Muslims.’

b. ES UNA PENA QUE EN MI AMADO ECUADOR ESTÁ ESTE SECTA TERRORISTA

‘It is such a shame that this terrorist sect is [found] in my beloved Ecuador.’

c. No entiendo como permiten la entrada de estos fanaticos religiosos que a lo que adoran es al mismo diablo, fuera de aquí!

‘I don’t understand how they permit the arrival of these religious fanatics who worship the devil himself. Get out of here!’

Seventh, there is the strategic use of orthographic conventions for rhetorical effect. This oftentimes occurs through the use of capitalization of every letter to imply seriousness, the use of quotation marks to suggest incredulity, the use of asterisks in place of vowels to ‘avoid’ writing the actual word (cf. G-d in English), or the use of multiple question marks and/or exclamation marks to indicate that the burden of explanatory responsibility is upon the representatives of Islam, i.e. the moderator of the Facebook page.

(12)a. ME PREGUNTO QUE TIENE ESTE SEÑOR DE “SANTO” CUANDO SABEMOS QUE NO DEFIENDE LOS DERECHOS DE LAS MUJERES MUSULMANAS QUE SON PERMANENTEMENTE MALTRATADAS POR LOS HOMBRES?

‘I wonder, how can this man claim to be godly when we know that he doesn’t defend the rights of Muslim women who are perpetually abused by men?’

b. al menos lee el Coran, esa r*ligión es nefasta

‘At least read the Qur’ān. That religion is [downright] evil.’

c. Fuera M*ros y s*rrac*nos ¡Viva Cristo Rey!

‘Get out of here, Moors and Saracens. Long live Christ the King!’

d. Llevamos nuestras propias mochilas bomba o alla nos las dan ??? Jajajaja

‘Do we bring our own [portable] backpack bombs, or will they give them to us there? Hahahaha’

e. pero en el sagrado Corán expone que Jesus (P) fue elevado a los cielos??

‘But the sacred Qur’ān explains that Jesus was raised to heaven?’

f. O sea que a los infieles hay que matarlos!!! Dios me libre de una religión así

‘In other words, kill the non-believers! God [protect] me from such a religion.’

Eighth, there are, of course, salient tropes of anti-Muslim rhetoric-in particular, specific references to acts of (supposedly) religiously-sanctioned violence, pedophilia, the lack of human rights for women, and anti-Semitic beliefs. Although most comments that addressed violence refer to literal explosions and/or explosive devices (13a-c), others rely on metaphorical interpretations (13e-f) or the use of word play (13g). For instance, although (13c) offers a warning that a literal explosion could result from one’s association with Muslims, (13g) presents an attempt at humor by deliberately modifying the wording of the Takbir (‘Allāhu akbar’) to call attention to the fact that a significant number of fundamentalists have uttered these same words immediately prior to committing an act of violence.

(13)a. alguno que me enseñe a hacer bombas?

‘[Will] someone teach me [how] to make bombs?’

b. Viene con manual para hacer explosivos?

‘Does it come with a guide to making explosives [bombs]?’

c. cuidado que van a explotar

‘[Be] careful - they’re going to explode.’

d. Mi hijo exploto mas fuerte que el tuyo jajaja

‘My child blows up [better] than yours, hahaha.’

e. voy a explotar de la emocion

‘I’m going to explode from excitement.’

f. Va a ser una reunión explosiva jajajajajajajaja

‘It is going to be an explosive meeting, hahahahahahahaha.’

g. Ala ak bar boom

h. El primer dia te enseñan a decir. Allahu akbar. Boom. No mentira. Significa. Dios es grande. Pero. Por lo regular lo dicen cuando. Hacen boom Jajaja

‘They teach you on the first day to say Allāhu akbar. Boom. No lie, it means God is great, but they normally say it then - when they go boom, hahaha.’

Furthermore, explicit suggestions that Islam results in fewer rights for specific marginalized groups are recurring, especially for members of the LGBTQ+ community (14a) or for women more generally (14b). Incidentally, there are media-based comments provided that emphasize this by e.g. representing a young girl observing hijab while holding an AK-47. Nevertheless, should one not conform to the norms of Islamic society, he or she will face severe consequences, including capital punishment, as in (14b). Furthermore, additional remarks insinuate that a woman’s quality of life is severely diminished from childhood if born within the fold of Islam (dar al-Islam), and support for this view is provided e.g. by referencing the age of A’isha, the daughter of Abu Bakr and the third wife of Muhammad (pbuh), upon the consummation of her marriage to the Prophet.

(14)a. vete a un estado islamico a ver si te dejan hablar... o cuanto tiempo duras con cabeza. Y si quieres hablar de los gays o los derechos de las mujeres...te mandan al cielo en avión

‘Go to an Islamic country to see if they let you talk - or how long you can keep your head. If you want to talk about homosexuals or the rights of women, they will send you to heaven by airplane.’

b. asi sr [sic] pobres mujeres obligadas a casarse de niñas y si no quieren ven cualquier horror y la matan a piedrasos

‘That’s how it is, sir. Poor women who are forced to get married as children and, if they don’t want to, then something horrible happens and they are stoned [to death].’

c. Una religion cuyo profeta de 53 años se casa con una niña de 7 años y la viola a los 9 es un culto despreciable

‘A religion whose fifty-three-year-old prophet marries a seven-year-old girl and rapes her [consummates the marriage] when she is nine-years-old is a despicable cult.’

d. El islam permite abuso sexual a niñas con el disfraz de matrimonio. El islam fundamentalista es perverso

‘Islam permits sexual abuse against girls under the guise of marriage. Fundamentalist [extremist] Islam is perverse.’

Finally, although an earlier facetious remark demonstrated a user’s interest in taking a course on Hebrew (instead of Arabic), there are other references to the widespread belief that Muslims are anti-Semitic, particularly against those who profess the Jewish faith. Although the leaders of a few Muslim-majority nations have indicated disbelief that the Holocaust actually occurred, this is not a religiously-sanctioned position but remains part of the widespread, uninformed knowledge of Muslims as a collective group, as in (15).

(15)Me molesta el hecho de que niegan el holocausto judío

‘It bothers me that they deny the Holocaust [of the] Jews.’

Furthermore, the exchange in (16) followed a discussion for an interfaith event. The first comment appears to be a genuine question; the second comment, a response that foregrounds the fact that many Muslims adhere to a different set of gustatory preferences (e.g. pork products are not considered halal), despite the fact that both fritada and hornado are recognizably Ecuadorian pork-based dishes. The third comment, however, is perhaps more interesting yet, as there are two possible readings. The first, unlikely reading is that the shawarma is prepared in a distinctly Jewish style. The second, more likely reading, particularly given the context in which it appears, is that the shawarma is prepared by placing someone Jewish on the rotisserie/spit, i.e. a simultaneous commentary on the primacy of pork in Ecuadorian cuisine and also upon the (assumed) anti-Semitism embodied by Muslims.

(16)que van a dar de comer

Ni idea, pero ni fritada ni hornado, de eso si estoy seguro

shawarma de judio a la brasa

‘What kind of food are they going to offer?’

‘No idea, but neither fritada nor hornado - I'm sure of that.’

‘Jewish shawarma on the grill.’

Ninth, there are references made to the perceived obsolescence of Islamic beliefs and value systems, particularly because they are believed to be both outdated and incompatible with contemporary Ecuadorian society. Although (17a-b) begin with hedges, these are only provided as perfunctory, face-saving attempts to lessen the impact of the negative criticism that immediately follows. Others, like (17c), neither begin with a hedge nor give the illusion of bridge-building.

(17)a. Con todo respeto, preceptos anacrónicos, de hace 1500 años

‘With all [due] respect, [you’re talking about] anachronistic beliefs from 1500 years ago.’

b. No muchas gracias, conceptos del siglo VII en el siglo XXI no tienen sentido.

‘No, thank you very much. [Beliefs] from the seventh century do not make sense in the twenty-first century.’

c. eso hicieron ustedes con los cristianos de las tierras que conquistaron y eso hacen los de su estado islamico . Lárguense moros

‘That’s what you did with the Christians in the lands that you conquered, and that’s what they are doing in your Islamic State. Get out, Moors!

Tenth, there are general references to the differences between Ecuadorian culture and the generalized, media-promulgated understandings of the lifestyles of Muslims more broadly. Some of these were presented earlier that foregrounded the use of religiously appropriate garb and the types of food consumed, but (18a-c) explicitly stipulate that there are simply insurmountable religious and linguistic differences that will prevent Muslims from ever coexisting peacefully in Ecuador. Unsurprisingly, it is assumed that all adherents of the faith will insist upon the implementation of Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh) at a national level (18a), there is a lack of awareness of the shared Abrahamic roots of Christianity and Islam (18b), and a belief that Muslims do not actually want to be understood in Latin America (18c-d). Oddly, the comment in (18d) argues against the use of Arabic simply from a potentially economic, utilitarian perspective.

(18)a. Ecuador es un país cristiano, el Islam es el enemigo. La Sharia es una aberración

‘Ecuador is a Christian nation, and Islam is the enemy. The Shari’ah is an aberration.’

b. Ellos no creen en Jesucristo como Salvador de la humanidad y el Dios de ellos ( Ala ) no es el mismo de nosotros los cristianos

‘They don’t believe that Jesus Christ is the savior of humanity, and their God (Allah) is not the same as our Christian God.’

c. Sí quieren llegar a ser comprendidos por los latinos, hablen en español

‘If you want to be understood by Latinos, speak in Spanish.’

d. Me preocupa que grupos musulmanes quieran adoctrinar su religión en Ecuador por que a nosotros no nos interesa su idioma porque no es universal como el ingles solo lo utilizan de señuelo

‘I’m concerned that Muslim groups want to indoctrinate [us with] their religion in Ecuador because none of us are interested in their language because it isn’t universal like English. It’s just used as a decoy.’

f. Vayan con sus ideologias a su pais, si un cristiano va a tu pais lo matan queman las iglesias son perseguidos, aquí entran como en su casa y quieren inponer su religión, nunca aceptaremos porque no nos entendemos

‘Take your ideologies [back] to your country. If a Christian went to your country, you’d kill him. You’d burn the churches. They [Christians] are persecuted. You come here like it’s your house and want to impose your religion. We will never accept [you] because we don’t understand one another.’

Solidarity-Building with Muslims

Although the primary objective of the present study is to demonstrate precisely how Islamophobic comments are constructed and shared on the public page of La Comunidad Musulmana Ahmadia, especially given how disproportionately represented they are to any other type of comment, it would be disingenuous not also to share briefly how Muslims and non-Muslims occasionally came to the defense of the faith and/or adherents more generally. Nevertheless, there were only four noteworthy ways in which these arose.

First, criticism of Christianity was offered as a way of undermining the platform of those waging criticism against Islam (19a-c). This was not particularly effective, especially given subsequent responses by those who cited decontextualized Qur’anic scripture or by those opposed to all religions simply as a matter of principle.

(19)a. Puede que los integristas sean los cristiano

‘It could [be] that the fundamentalists are [actually] the Christians.’

b. después de que los cristianos maten a personas en las cruzadas hermano

‘[the class is] after the one [that teaches] how the Christians kill[ed] people during the Crusades, brother.’

c. la pedofilia no es exclusiva d ellos. últimamente saltan como canguil casos d abusos sexuales d sacerdotes católicos a niños...supuestos vicarios d cristo

‘Pedophilia is not exclusive to [Muslims]. The cases of sexual abuse recently have been popping like popcorn-of Catholic priests with children-so-called vicars of Christ.’

Second, those who practice no religion at all or who are opposed to all religious traditions indicated a desire to build solidarity with Muslims and/or members of other faiths either by offering a kind word (20a) or by conceding that Islam might even provide an attractive perspective for viewing or navigating the world (20b).

(20)a. Soy ateo respeto a todo ser humano y religion..saludos hermanos musulmanes

‘I am an atheist who respects all humanity and religion. Greetings, Muslim brothers.’

b. Créeme soy atea pero me atrae el punto de vista de está religión

‘Believe me, I’m an atheist, but I’m drawn to this religion’s point of view.’

Third, legitimate defenses of Muslims were sometimes undertaken, especially against those who were spreading hate (21a) and against those who might not be speaking from an informed position (21b). On other occasions, there were token defenses through deflection, as in (21c), which presents a redefined equivalence between terrorist and gringo10. In this case, the gringos are the actual terrorists (i.e. not the Muslims) and, because terrorists are unwanted in Ecuador, will be prevented from residing in the country.

(21)a. que te pasa xenófoba religiosa??? Pon comentarios de odio religioso en otro lado...!

‘What’s wrong with you, religious bigot? Put your hateful comments [toward] religion somewhere else!’

b. Wow, el odio que tienes es impresionante. ¿Cual historia? ¿Donde dice en el coran tanto odio? Realmente tienes que tomar un respiro.

‘Wow, your hatred is impressive. Which history? Where in the Qur’ān does it show such hatred? Really, you need to take a [deep] breath.’

c. No quieren terroristas pero aceptan a los gringos que son los verdaderos TERRORISTAS

‘They don’t want terrorists [here], but they accept the ‘gringo’ [Americans] who are the true TERRORISTS.’

Fourth, there are some limited attempts to correct misunderstandings or a lack of knowledge. Many people erroneously believe that Muslims do not believe in Jesus (pbuh) or, as mentioned earlier, that Muslims pray to a different God than those of the other Abrahamic religions. The comment in (22a) tries to acknowledge that Jesus plays a significant role in Islam and calls attention to the other major figures in the Bible, who are similarly perceived as prophets by Muslims. Moreover, the prosaic comment in (22b) provides a defense of Muslims generally and calls attention to the problematic nature of conflating all Muslims with extremists or strictly with those of Arab ancestry11.

(22)a. pero para ser un musulman, es necesario creer en la Biblia y en Jesus y todos los profetas en la biblia

‘But, in order to be a Muslim, [one] has to believe in the Bible, in Jesus, and in all of prophets of the Bible.’

b. muchas personas tienen la errónea idea de que musulmanes, islámicos, yihadistas y árabes son lo mismo...yo conocí muchos amigos musulmanes y son muy buenas personas, migrantes viven en Ecuador y hacen su vida sin molestar a nadie

‘Many people have the erroneous idea that Muslims, Islamists, Jihadists, and Arabs are the same. I’ve met many Muslim [people], and they are very good people. Migrants live in Ecuador and go about their lives without bothering anyone.’

CONCLUSION

The present study has demonstrated how a sociologically-minded, critical discourse analytic approach to online social media can yield conclusions beyond those readily understood at face value, extending beyond superficial dichotomies and, considering how Islamophobic discourse, when manifested, reflects an underlying ideological taxonomy. In particular, a study was made here of the top 10 comment-provoking statuses on the Facebook page for La Comunidad Musulmana Ahmadia, which serve as a statistically significant, representative sample of the total number of posts. The results indicate that there are 10 discursive strategies consistently employed to share Islamophobic beliefs and four recurring discursive strategies employed to build solidarity with Muslims. Ultimately, however, the former is disproportionally represented, resulting in a reification of the divide between those who are in power or powerless, who are similar or different, who are the aggressors or victims, and who are united with Us or distanced among Them.

This results, of course, in “a series of crude, essentialized caricatures of the Islamic world presented in such a way as to make that world vulnerable to military aggression” (Said, 1980, par. 11). As such, the ‘insider’ is defined as a civilized, modern, honest native speaker of Spanish who reads the Bible and practices Christianity. On the other hand, the ‘outsider’ is defined as a backwards, outdated, opportunistic foreigner who speaks Arabic, discriminates against women, reads and blindly follows the teachings of the Qur’ān, has ancestral or social roots in the Middle East, and will never be accepted into mainstream Ecuadorian society, thus perpetually existing as a member of a perceived fringe, minoritized group. In fact, this serves as evidence for Said’s (1978/2003) 40-year-old statement that Islam and, by extension, Muslims are “viewed as belonging to a part of the world-the Orient-counterposed imaginatively, geographically, and historically against Europe and the West.”

While the present study has introduced the first formal treatment of Islamophobic speech in an Ecuadorian context, there are, however, additional areas where future research could be advantageous. For instance, there was no attempt here strictly to engage the implications of every instance of cited scripture, nor does the present study consider the possibility of such discourse outside of the Muslim community in Quito-as the reader might recall, there are also existing masjid in Guayaquil and Cuenca. Furthermore, qualitative interviews and surveys among Muslims and non-Muslims in Ecuador could shed additional light on the relationship and/or tension between these otherwise different ethnic, linguistic, cultural, and religious groups. Finally, the social and/or legal implications of the existence of comments like those presented here have not been investigated yet, though the right to practice one’s own professed religion (or lack thereof) and to be free from intolerance and discrimination are rights protected under Articles 11, 19, 66, and 174 of the Constitución de la República del Ecuador.