INTRODUCTION

In present-day society, critical literacy is considered a ‘new basic’ that students must develop to deal effectively with the numerous multimodal and multimedia texts they are exposed to every day, thus enabling them to examine and contest such texts (Luke, 2019). New communication technologies such as mobile devices, internet, and social networks have also helped democratize the production of meaning, contributing to both the reproduction of powerful discourses and the dissemination of counter-discourses (Janks, 2012). As consumers and producers of texts, it is important for students to develop critical literacy so that they can familiarize themselves with the meaning-making resources used in such texts, and understand the role of language in construing power relations in terms of gender, ethnicity, and class, among others (Vasquez et al., 2019).

As educators working in this challenging context, language teachers should find ways to help students learn the language while developing their abilities to use, critique, and design texts using various semiotic resources and addressing issues of cultural, social, and political power (Luke & Dooley, 2011). Hence, teachers should apprentice students into developing control of everyday and academic texts so that they can gain access to the dominant discourses in which they might be embedded, thus fostering their awareness of texts’ different purposes, audiences, meaning-making resources, and potential social effects (Hyland, 2003; Kalantzis & Cope, 2012). Moreover, they should help students understand that texts are not neutral, find out how texts position them, and unveil and contest the ideological representations of the world that texts promote (Luke, 2012).

Aware of this need, a small group of EFL teachers in Colombia working in tertiary education settings have already started to explore the implementation of classroom strategies to help students develop critical literacy. For instance, Agudelo (2007) helps a group of pre-service teachers develop awareness of the cultural and linguistic diversity present in the EFL classroom through the analysis of the relationship between language and culture. Gutiérrez (2015), in turn, explores the beliefs and attitudes of pre-service teachers towards the design and implementation of critical literacy lessons in public schools during their practicum year. Similarly, Rojas (2012) examines the interactions of female students in a private university to explore the influence of gender identities and power relations in the English language learning process. Finally, Rondón (2012) analyzes the narratives of LGBT students from different universities to identify the moments in which issues of gender and power emerged in the EFL classroom.

Despite the benefits these attempts might have brought to students in terms of helping them develop critical literacy, they have emphasized the dimensions of power and diversity rather than attempting to address these simultaneously and interdependently with the dimensions of access and design, as suggested by Janks (2010). In other words, although they have helped students understand issues of power, raise their critical cultural awareness, and examine texts from different perspectives, these attempts have not explicitly helped students gain control of genres highly valued in university contexts (access), nor enabled them to use multiple meaning-making resources to construct texts which challenge existing discourses and contribute to social transformation (design).

Hence, the purpose of this qualitative study was to explore the effects of implementing a critical literacy unit, designed following Janks’ synthesis model, with a group of university EFL students. Specifically, it aimed to see how such an intervention helped students reflect and discuss issues of gender stereotyping (power), gain familiarity with the genre of expository essays (access), capitalize on their diverse assumptions and experiences about such topics (diversity), and use a wide range of language resources to produce expository essays about female stereotyping (design). The following sections present an overview of the theoretical underpinnings of this study, a description of the critical literacy unit, the methods of data collection and analysis, the findings and discussion, and the conclusions.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Critical Literacy

Critical literacy involves imagining different forms of construction and reconstruction of texts to transmit different messages with greater social justice and equity, amplifying effects on real life (Vasquez et al., 2019). This implies an attitude towards texts that goes beyond a mere set of methods, skills or techniques, allowing people to take a stand and be able to support, reject, adapt or reshape texts (Janks, 2010; Luke & Dooley, 2011). According to Luke (2012), critical literacy has been mainly developed from two broad approaches: critical pedagogy and text analytic models. The former draws on Freire’s idea of education as a liberating and transformative tool, which challenges the traditional view of being literate as using, spreading and perpetuating dominant representations of the world. The latter focuses on the teaching of how texts work to position consumers ideologically through semiotic resources, ideological content and varied discourses.

Despite the differences between these two approaches to critical literacy and their various applications, they are not mutually exclusive (Luke, 2012). In fact, Janks (2010) argues for a model of critical literacy that pursues the integration of different perspectives of critical literacy, which represents an attempt to integrate critical pedagogy and text analytic models.

Janks’ Synthesis Model of Critical Literacy

This study draws on Janks’ (2010) synthesis model of critical literacy in which she advocates for the interdependence of the four orientations in critical literacy education: power, access, diversity and design. Janks notes the problematic imbalance of any of these dimensions without the others (Janks, 2010). A brief description of these four dimensions is provided below.

Power

Power refers to the dimension of critical literacy that promotes the exploration of the ways in which texts are used to maintain and reproduce power relations in terms of language, gender, race, class, and ethnicity, and how they may work in the interests of some privileged social groups over others (Janks, 2009; Wallace, 2010). Accordingly, critical literacy teachers help students develop literacy skills to examine how such relations of power are displayed in texts so that they can read in agreement with or against them. Since language often works to position audiences in the interests of power, readers/listeners should question the reasons why the writer/speaker made certain language choices and who is empowered and disempowered by such choices (Janks, 2010). This implies that students need to develop better awareness of how texts work to position them, and also analyze how this positioning might privilege some audiences over others (Janks, 2009).

To help students unveil how language positions them in relationship to power, Janks et al. (2014) suggest activities that help students explore the social impact of texts, as well as the embedded worldviews, beliefs, values, actions, and languages, which may position students ideologically. Positioning should also consider how our ethnicity, gender, age, economic status, among other social features have an effect on the way we see the world. Janks et al. (2014) also suggest exploring this social positioning through activities such as debates and discussions where the different positions can be visualized, and the differences among members of a group can be recognized, including questions such as the following: How is the text positioned or positioning? Whose interests are served by this positioning? Whose interests are negated? What are the consequences of this positioning?

Access

Access refers to the need to provide students with greater access to dominant languages, discourses, knowledge, genres, and a wider range of cultural practices (Janks, 2010). Delpit (2006) suggests that explicit teaching of the linguistic forms and ways of talking, writing and interacting that are dominant in schools and workplaces, makes access easier for those who are not participants in such a “culture of power”. Accordingly, genre scholars, especially those from the Sydney school, have identified and classified highly valued school genres within three families: stories (e.g., narratives), factual texts (e.g., explanations), and evaluating texts (e.g., expositions) (Martin & Rose, 2012).

To help students gain access to such genres, genre scholars have developed a pedagogy known as the teaching and learning cycle (Hyland, 2003; Martin, 2009). The cycle comprises three main stages: deconstruction, i.e., guiding students to explore the cultural context, stages and language features in model texts; joint construction, where teachers guide the whole class to write another text in the same genre; and independent construction, in which students write their own texts. In doing this, teachers promote access to mainstream genres which would help shift power by redistributing discursive resources (Martin, 1999).

Of these genres, expository essays are one of the most highly prized in academic contexts (Andrews, 2010). Gaining access to this genre implies that students learn how to state and argue a viewpoint through three stages: thesis, arguments, and reiteration (Martin, 2009). Each stage further unfolds in phases: The thesis stage includes a thesis statement and a preview of arguments; each argument in the arguments stage is developed through the phases of point and elaboration; and the reiteration stage restates the thesis and summarizes and evaluates arguments. Writing effective expositions also requires students to use the expected language features of the genre, including generalized abstract nouns, varied verb types, conjunctive resources, declarative mood, passive forms, and modals (Derewianka & Jones, 2016).

Diversity

Diversity has to do with the multifarious ways in which human beings interpret and represent the world which, in turn, reflect humans’ diverse ways of being, thinking, doing, and valuing, including their social identities (Janks, 2010). Such identities are shaped by the discourses of the communities we inhabit, and implies behaving in accordance with what community members consider is correct; thus, belonging to different discourse communities results in the development of fluid and hybrid identities (Janks, 2010). As this diversity is usually subjected to relations of power, critical literacy teachers should enhance students’ own ways of reading and writing the world, help them reflect on how these different social identities might be privileged or marginalized, and encourage them to immerse themselves in new discourses from which they can learn new ways of being and acting in the world (Janks, 2010).

To achieve this purpose, Janks et al. (2014) and Janks (2010) suggest classroom activities that promote the understanding of how our own and others' social identities have been shaped differently, and how language and discourse are often used to position “the other” negatively, leading to injustice, oppression and even genocide. Teachers and students should also reflect on how some people are included while others are excluded by languages and dialects, and how our tendency to classify people and rank them brings inequality because of the construction of some as better than others.

Design

Design refers to the ability to produce texts for different purposes, audiences, and contexts, using and combining a wider range of available semiotic resources to dispute and transform existing discourses (Janks, 2010). This ability is crucial for students’ development of critical literacy since it promotes agency, enhances their understanding of how texts work to achieve goals, enables them to actively combine and recombine available symbolic forms, helps them explore ways of positioning themselves and their readers, and empowers them to transform the texts they have already deconstructed (Janks, 2010). Design, then, is not merely about reconstructing texts, but is about using transformative social actions to remake the social world (Janks et al., 2014).

To help students do this, critical literacy teachers can ask them to consider alternative versions of a story, for example, and write their own versions of the ending, or to deconstruct and reconstruct texts that may be considered racist or sexist, or write letters or stories as a form of social action (Janks, 2009). Teachers can also have students work on classroom projects that encourage them to design and redesign texts by integrating verbal, visual, aural, spatial, and gestural modes of communication, as well as engaging with a variety of media (newspapers, television, internet, radio, magazines) and digital technologies (Janks, 2010).

When addressing the dimensions of power, access, diversity, and design, Janks (2010) argues that teachers must consider their interdependence and warns them about the problematic imbalance of pursuing one without the others. However, although teachers should address these dimensions simultaneously, they could also work on just one at a time as long as they give equal weight to each dimension in the curriculum to achieve a well-balanced critical literacy experience for students. Examples of implementations of Janks’ synthesis model are presented below.

Implementations of Janks’ Synthesis Model

Janks’ model of critical literacy has been implemented for several educational purposes in various school contexts. In elementary schools, for instance, the model has been used to understand first-graders’ resistance to the dominant genres of reports and narratives (Hultin & Westman, 2013), help sixth-graders deconstruct ideologies in short films (Mantei & Karvin, 2016), examine teachers’ influence on the development of reflective competence in fourth-graders (Svensson, 2013), explore the effects of teachers’ writing instructions on sixth-graders’ access to the genre of letters to the editor (Lundgren, 2013), and analyze how national tests and language syllabi may promote critical literacy (Ekvall, 2013). Similarly, at middle and high school level, Janks’ model has been useful in exploring English as an Additional Language teachers’ orientations to critical literacy (Alford & Jetnikoff, 2016), teachers’ and learners’ discourses when interpreting advertisements (Mbelani, 2019), and English Language learners’ development of critical literacy while addressing issues of discrimination and cultural adjustment (Lau, 2013).

In tertiary education, Chun (2017) has used Janks’ model to help college students in Hong Kong explore the dynamic of writer-reader relationships (power), gain familiarity with the structure and language of formal business memos (access), discuss issues of workplace discriminations (diversity), and write proper business emails (design). Reid (2011) analyzed the writing of tutors and students in closed-group tutorial Facebook pages used in a South African university, to see how such tutorial groups changed power relations (power), encouraged students’ use of the language they typically used on Facebook (access), promoted the use of their own text coding practices (diversity), and allowed them to redesign concepts in their own codes (design). Finally, Prins (2017) examined to what extent a digital storytelling class in an adult education program integrated Janks’ four dimensions of critical literacy and found that, although the class did not focus on issues of domination, the teacher raised awareness of Google’s interests behind the internet ads appearing in search results (power). The author also found that learners increased their linguistic and technological resources to design digital stories (access), were allowed to draw on their life experiences, native languages and cultural identities (diversity), and used a range of semiotic resources to produce their stories, including images, visual effects, and transitions (design).

METHOD

This qualitative study aimed to explore the effects of implementing a critical literacy unit designed under the lens of Janks’ synthesis model with a group of university EFL students. More specifically, it focused on analyzing students’ reflections on issues of gender stereotyping, examining their ability to comply with the purpose and structure of expository essays, identifying their diverse viewpoints, and identifying the language resources they used to challenge common gender stereotypes. The study falls into a qualitative paradigm since it pursued the study of a group of human actors in the context of their ordinary everyday world (Richards, 2003). It also complies with the characteristics of an instrumental case study since it finds a case to explore a particular real-life issue through detailed data collection, including multiple sources of information, and gain further understanding of it (Creswell & Poth, 2018), so that findings could potentially be generalized to other similar cases (Mertens, 2015). Accordingly, this study explored the implementation of a critical literacy model in a university EFL classroom, thus providing insight as to how critical literacy might be developed in similar educational settings.

Context and Participants

This study was conducted at the language center of a private university located in Rionegro, Colombia, in 2018. The center offers nine levels of English courses (comprising 40 in-class hours per level) organized around Oxford English File textbooks (elementary, pre-intermediate, and intermediate), and designed to help students achieve CEFR-B1 level. The intervention proposed in this study was implemented at the English course Level 8 (semi-intensive at six hours per week) with the thematic and linguistic content aligned to that of Units 9 to 12 in the Oxford English File pre-intermediate textbook. Specifically, the implementation addressed the topic of women inventors, as well as grammar topics such as passive voice and modal verbs, which are part of Unit 10.

The participants were a group of 14 EFL students, five women and nine men, mainly from a middle-low socioeconomic background, and whose ages ranged from 18 to 29. Eleven of them were undergraduate students of business administration, social communication, environmental engineering and agricultural sciences at the university. Two were graduates wanting to pursue postgraduate studies. The last was a high school graduate planning to start university the following semester. In general, their level of English proficiency was heterogeneous. Both the context and the participants were purposefully selected for the following reasons: the convenience of the site, which was the workplace of one the researchers, thus facilitating access; the English course syllabus and mainstream textbook, which may potentially represent EFL teaching practices in other institutions in Colombia; and the group of students, who were English language learners at university level.

The Critical Literacy Unit

To help this group of EFL students develop critical literacy, an instructional unit was designed and implemented by the main author of this article, following Janks’ (2010) synthesis model, under the guidance of the co-author who was also the main author’s thesis advisor. This implied incorporating Janks’ four dimensions of power, access, diversity and design into the development of the English course described above, specifically the thematic and linguistic content of Unit 10 from the English File pre-intermediate textbook, expected to be covered in the course. The unit was organized into four lessons (a total of eight class hours during two weeks) that included activities to promote reflections and discussions around gender stereotyping issues (power), help students gain familiarity with the genre of expository essays (access), explore students’ diverse assumptions and experiences about such issues (diversity), and encourage the use of diverse language resources in their expository essays to take a stance towards common gender and specifically female stereotypes (design). Table 1 provides an overview of the unit.

Table 1 Overview of the Critical Literacy Unit

| Lesson | Topics | Objectives | Activities |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Male and female inventions and students’ assumptions about gender roles | To explore students’ previous knowledge and assumptions about male and female inventors. To reflect and discuss about gender issues related to everyday use inventions. | Whole class discussion: students’ assumptions on male and female inventions and social gender roles. |

| Listening to a radio interview about male and female inventions and comparing the given information to students’ previous assumptions. | |||

| Completion of Worksheet 1: finding out about other inventions and their inventors. | |||

| Reflection and whole class discussion: Why do men’s inventions outnumber those of women? What challenges have women faced in the past. | |||

| 2 | Expository essays | To trigger students’ previous knowledge of and experience writing essays. To introduce students to purpose, structure, and language resources of expository essays. | Completion of Worksheet 2: students’ experiences writing essays and their knowledge of purpose and structure of essays. |

| Whole class discussion: sharing, comparing and discussing students’ answers in worksheet 2. | |||

| Analysis and deconstruction of a model essay: structure, arguments, and language choices. | |||

| 3 | Women’s representation in TV ads | To examine gender stereotypes in TV advertisements. To jointly construct an expository essay. | Analysis of a 1968 Xerox copiers TV advertisement. |

| Whole class discussion: discussing women’s representation in the TV ad analyzed and selecting a topic for the whole class to write an essay together. | |||

| Joint construction of an essay on the selected topic: "women are not as strong as men". | |||

| 4 | Challenging women stereotypes | To engage students in the independent construction of an expository essay on gender stereotypes. To identify and correct issues in essays’ first drafts. | Selecting a gender stereotype to write about. |

| Writing the first draft of an expository essay. | |||

| Providing feedback on the first draft. | |||

| Making corrections and submitting the final essay. |

More specifically, lesson one explored students’ previous knowledge of inventions of everyday items and their assumptions about male and female inventors. To do this, they first engaged in a talk about the inventions they used every day, their assumptions about which inventions they thought might have been invented by women and why, and their opinions on the roles of men and women in society. They then listened to a radio interview about inventions made by women and discussed their assumptions considering the interview. Next, in pairs, students completed a first worksheet in which they found out about other inventions and reflected on why men’s inventions outnumber women’s, what challenges women have faced in the past, and those they face in the present day. Finally, students had a whole class discussion around these questions.

Lesson two introduced students to the purpose, structure and language resources of expository essays. To do this, they were first asked to complete a second worksheet with questions such as “What is an essay?” “Are there different types of essays?” “Have you ever written an essay? What for?”, among others. After having a whole class discussion on this, a sample expository essay about the benefits of video games for teenagers’ health was deconstructed. This sample text was considered a suitable model of the target genre as it complied with the expected generic structure and language features of expository essays. Students read aloud the sample text and discussed how it was structured, how arguments were organized, and which language choices were made.

Lesson three modeled the process of writing an expository essay for students. To do this, students first watched an advertisement about the 1968 Xerox copier and analyzed what the woman in the ad said about herself, her occupation, her boss, and the machine. Students examined and discussed how language was used here to position women as less powerful than men. Afterwards, the whole class agreed to write a text together about the common belief that “women are not as strong as men”, implied in the Xerox ad. Considering their own life experiences, students discussed and agreed to take a concerted stand against this stereotype. They were then asked to provide arguments to support their position. As they delivered their ideas, the teacher compiled and organized their contributions to jointly construct an expository essay, projecting the text on a wall in the classroom.

Lesson four engaged students in the independent construction of expository essays by gathering, summarizing, and synthesizing information from various sources, as well as using grammatical, stylistic, and mechanical formats and conventions appropriate for the genre. Before students started writing, they were provided with a list of common stereotypes about women in order to choose one to write their essays and encouraged to take a stance and develop their own arguments. Once they finished their first drafts, students brought them to the class to share and discuss with their classmates. They also received feedback from their classmates and teacher before submitting their expository essays.

Data Collection and Analysis

The data collection instruments used for this study were audio recordings of class sessions, interviews with students, and samples of students’ work. The four class sessions through which the instructional unit unfolded were audio-recorded to register students’ responses during discussions around gender stereotyping. Individual semi-structured interviews with four students -two men and two women with different levels of English proficiency- were carried out in Spanish to gather their opinions on the implementation of the unit and learn about what they gained and any challenges they experienced in developing critical literacy. Finally, samples of students’ work, including worksheets and expository essays, were collected.

Overall, the data analysis followed Burns’ (2010) five steps: assembling the data, coding the data, comparing the data, building meanings and interpretations, and reporting the findings. Accordingly, the audio recordings of class sessions and interviews were first transcribed and color-coded in MS Word documents. Students’ worksheets and essays were also color-coded manually. Specifically, essays were analyzed with a rubric which assessed their generic structure and language resources. The four dimensions of Janks’ (2010) critical literacy model (power, access, diversity and design) served as broad, pre-established categories that initially helped approach the data deductively. Afterwards, as coding and comparing data proceeded, themes emerged inductively within each pre-established category.

To enhance the reliability and accuracy of this study, all data sources were triangulated (Creswell & Poth, 2018). To do this, a table was created based on the four broad categories and, to reduce the amount of data, selected chunks of information from the different sources were added that fit into each category. The table also helped in examining and comparing the data within each category, to identify emerging themes and to find evidence to support them.

Ethical considerations

Before implementing the proposed critical literacy unit for this study, the language center coordinator and the participating students were requested to grant their written consent on the basis that the identities of the institution and participants were to be protected. Accordingly, all the names used in this article are pseudonyms.

FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

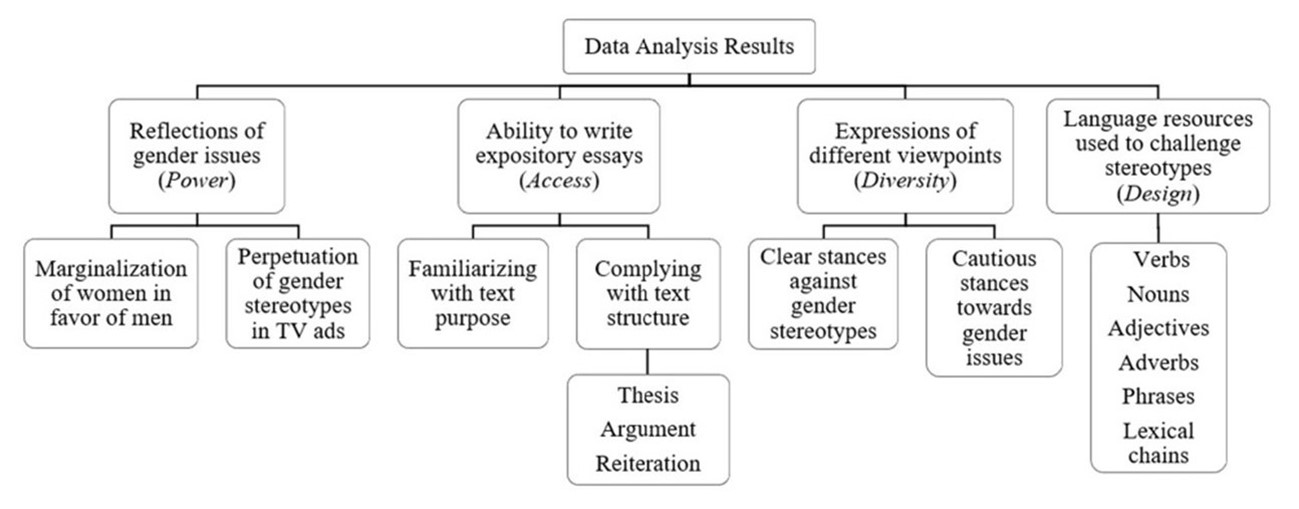

The analysis of the data collected in this study suggests that implementing a critical literacy unit based on Janks’ synthesis model enabled university EFL students to reflect critically on issues of gender stereotyping (power), familiarize themselves with the genre of expository essays (access), value students’ diverse assumptions and experiences about such issues (diversity), and produce expository essays to take their own stance towards common female stereotypes (design). Figure 1 depicts the results of the analysis. In the next lines, such findings are presented and discussed.

Reflecting on Gender Stereotyping (Power)

The dimension of power deals with understanding how unequal relations of power are maintained and reproduced in a particular society, how privileged groups are formed in accordance with the values of that society (e.g., maleness, wealth, and skin color), and how social institutions and their discourses (e.g., families, schools and the media) play a key role in persuading people to conform to such values and naturalizing power relations (Janks et al., 2014). Overall, the data in this study showed that students gained awareness of how power works in favor of men while marginalizing women, and how media discourses have contributed to the perpetuation of such unequal relations (Comber & Grant, 2018; Luke, 2018).

Indeed, at the beginning of the implementation, students showed that they carried gender stereotypes such as the traditional often inherited belief that women are responsible for housework and childcare, which is still common in Western societies (Robinson-Pant, 2016). For instance, during a classroom activity where students were asked to choose from a list of five inventions those they thought had been invented by women and explain why, they provided answers such as the following:

Mia: The zipper. Because women make or fix the clothes.

Teacher: ok

Logan: the hair drier because they [women] use.

Liam: the dishwasher because she [a woman] cleans the house.

Oliver: nappies because the women have the babies and clean the babies.

(Audio-recorded session 1)

Similarly, when asked for inventions that they believed were not made by women, Noah said that “the bullet proof vest because the soldiers and police are men” (Audio-recorded session 1). These answers show the latent beliefs about stereotyped social gender roles that students brought into the classroom, for example that repairing clothes, keeping house, and caring for children are female roles, and protecting others and enforcing the law are male roles.

During this study, students could reflect on such gender-stereotypical beliefs and see how they display the privileged position that men have traditionally held over women. In her essay, for example, Emma described how men were favored over women in her family when she was a child:

My paternal grandparents taught my father and his brothers that men prevailed over women, since I was a child when we went to family meetings, only the women were the ones who prepared the food then served the food and it was done in a strict order, first to my grandfather, then to the other men, later to the children and finally to the women. At the end of the dinner it was the women who were responsible for collecting the dirty dishes and washing them. (Emma’s essay)

In this excerpt, Emma shows that housework was aligned with female roles at home as “only the women” would cook and serve meals and “were responsible for” washing the dishes. In addition, she portrays a hierarchical relationship in which “men prevailed over women”, the latter serving the former “in strict order”. She also observed this relationship in her aunts, who “were always submissive to what their husbands said, they had never worked, and they always had depended economically on them” (Emma’s essay). Here, Emma correlates the submission of the women in her family with their economic dependency on their husbands.

Moreover, Emma noted that these stereotyped gender relationships in her family could still be seen in her current experience as a married young woman, as shown in the excerpt below:

Currently with my husband, I live a complex situation because he wants I do [sic] the kitchen tasks and housework, but not because he has the same thought of my father’s family … My husband works just like me, when he comes home he only thinks about investing his time in sports, resting and if he has some free time he cooks and does housework. (Emma’s essay)

Although Emma had a job, unlike the women in her family, and recognized that her husband was different to her family’s men, she could still perceive traces of gender stereotyping in his behavior, concerning the expected responsibilities of women, which caused discomfort in their relationship. Emma’s reflection on gender roles in her own family shows how female stereotypes, such as the viewing of women as responsible for housework, still persist despite women’s increasing access and growth in domains traditionally dominated by men (Bareket et al., 2021).

To help students gain awareness of stereotyped gender roles, they deconstructed TV ads to reflect on how such stereotypes are portrayed and perpetuated. As a result, students were able to explore how ads may use common gender stereotypes that downgrade and objectify women. For instance, in the following excerpt, Mia describes how she felt offended by the portrayal of women in TV ads as “commercial objects”:

That seemed to me…at some point I even felt like I was outraged because they always treat women as a commercial and advertising object, so at some point I felt like, “No way!” It makes me furious that we are being used for that when it is known that we are so useful for so many other things. (Mia’s interview)

Mia’s nonconformity with the stereotyped depiction of women in the TV ads analyzed in class shows a significant gain in identifying and questioning hidden messages which may represent women as caregivers, housemakers, self-sacrificing wives, and sexual objects (Khalil & Dhanesh, 2020; Sharda, 2014). Hence, helping students raise their awareness about gender stereotyping and develop their abilities in identifying hidden stereotypes in advertisements is key to educating them to become more critical and active, rather than passive, consumers of media (Puchner et al., 2015). Such awareness and abilities are even more relevant nowadays as we live in an information-saturated world where we can inadvertently imbibe and perpetuate existing inequalities between men and women (Sharda, 2014).

However, notwithstanding this gain, the data also showed that at least three students seemed to continue carrying such prejudices about women. For example, in his essay, James suggested that women possess attitudes and aptitudes that differentiate them from men, as shown in the excerpt below:

I think that this is happening because women want to do housework and cook, they generally have the capacity to be very organize [sic], they know how to have a place nice for people. Men don’t have the same capabilities. (James’ essay)

Here, James highlighted women’s inclination towards housekeeping, affirming that they “want to do housework and cook”, and their aptitude for organizing places, stating that they “have the capacity to be very organize[d]” and “have a place nice”. In his attempt to enhance women’s virtues, he seems to equate household chores with female roles, precisely the beliefs we said students had brought to the classroom.

Similarly, William stated in his essay that, although both men and women must have the same rights, “men are stronger for some tasks even more when it comes to using force” (William’s essay), implying that there are differentiated tasks for each gender. William’s and James’s viewpoints suggest that, even when recognizing the need for gender-equal rights and enhancing women’s virtues and capabilities, gender stereotypes may still prevail in the form of benevolent sexism in which men and women are believed to have different yet complementary attributes, but men still enjoy a privileged position (Shnabel et al., 2016).

As shown in this section, reflecting on and discussing gender-stereotypical beliefs helped students not only identify the promotion of such beliefs in TV ads, but also recognize that they may be perpetuating stereotypes that discriminate women in favor of men. Raising awareness of discrimination issues in the English language classroom, such as gender stereotyping, is essential for developing critical literacy (Huang, 2011; Wallace, 2010).

Gaining Control of the Genre of Expository Essays (Access)

The dimension of access involves, as Janks (2004) argues, the need for students to develop control of the elite literacies (dominant languages, genres, and modes of visual representation) required to perform symbolic-analytic work as it is more valued in the post-industrial knowledge economy. In academic contexts, particularly, expository essays are considered one of the most dominant and valued genres (Andrews, 2010). In the university EFL classroom, writing expository essays has been identified as a challenging task for students (Gómez, 2017; Kim, 2017).

The data in this study indicate that, through the proposed instructional unit, most students gained greater familiarity with the purpose and generic structure of expository essays. Indeed, although students had previous experiences writing essays in Spanish, their knowledge of the genre before this study was still limited, and even more so was their ability to write essays in English. Based on their answers in the second worksheet, Table 2 summarizes students’ prior knowledge and experience with essays.

Table 2 Students Previous Knowledge and Experience with Essays

| Aspects | Answers |

|---|---|

| Purpose | To express an opinion (5) |

| To express and argue your ideas (4) | |

| To explain your opinion (2) | |

| To discuss or expose a theme (1) | |

| No answer (1) | |

| Structure | Introduction ^ Development ^ Conclusion (2) |

| State a position ^ Present arguments (1) | |

| State the topic ^ Present arguments ^ Write a conclusion (1) | |

| Described the writing process rather than the structure (2) | |

| Doesn’t know / doesn’t remember (7) | |

| Previous Experience | have written essays only at the university (5) |

| have written essays at school and the university (4) | |

| have written essays only at school (4) |

Note. The numbers in paratheses indicate the number of students who provided that answer. Thirteen students out of fourteen answered the second worksheet.

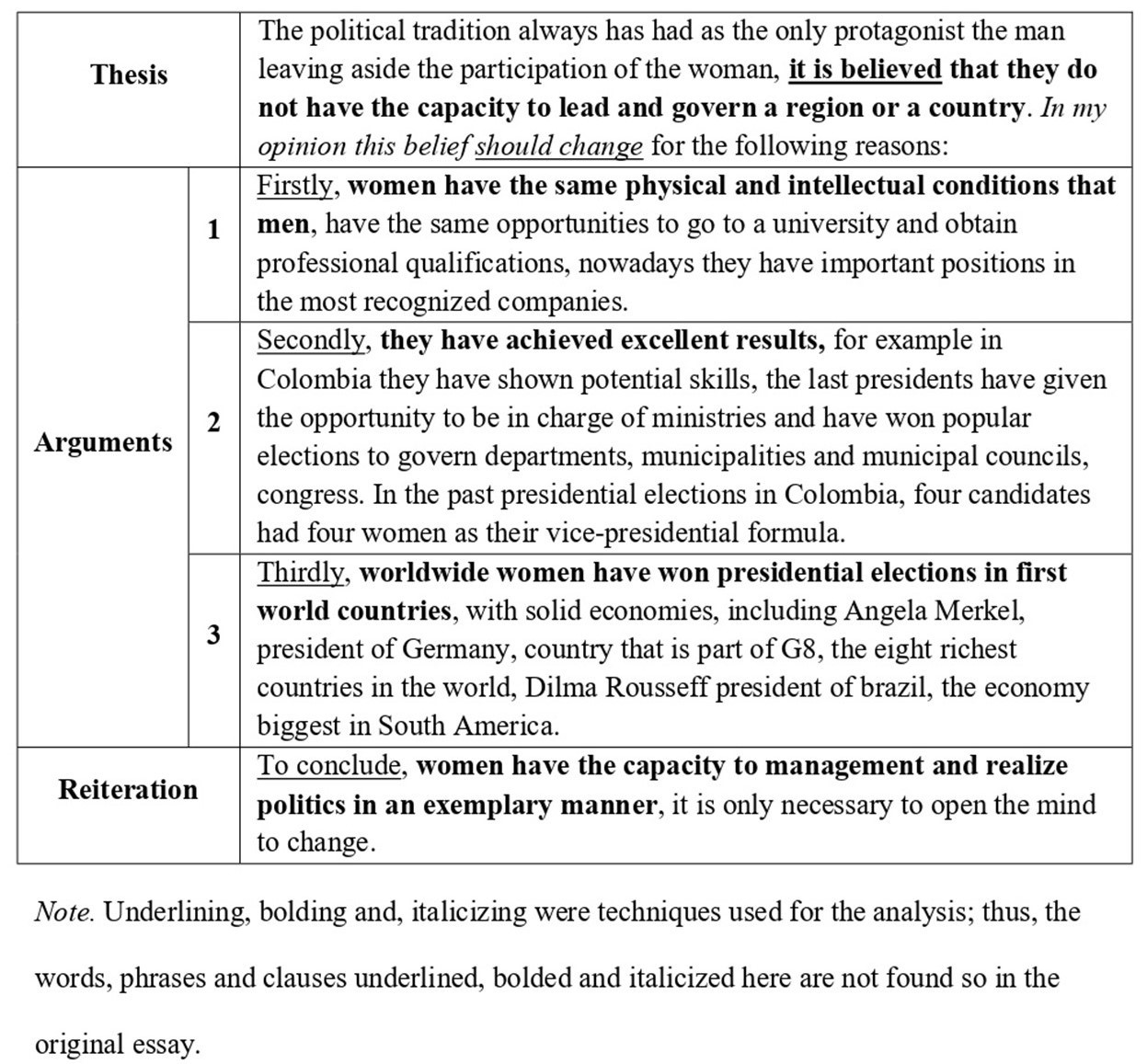

The understanding students gained could be observed in the way they structured their essays to achieve their purpose by first presenting a thesis and then developing the arguments to support it, as instructed during the lessons. For instance, as seen in Figure 2, Manson’s short essay about the prejudiced belief of women’s incapacity for politics included the expected stages for an expository essay: thesis, arguments, and reiteration (Martin, 2009).

In the thesis stage, Manson clearly introduces the target prejudice (see sentence in bold), women’s political incapacity, and asserts his position rejecting such a belief (see sentence in italics). In the next stage, arguments, he presents three arguments to uphold his position: 1) women are as capable as men; 2) examples of women’s political achievements in Colombia; and 3) examples of women’s political achievements worldwide. In the final stage, reiteration, he restates his position affirming that women do have the political capacity that has been commonly denied.

The analysis of Manson’s essay also showed that, despite instances of inaccurate punctuation and grammar, he used language resources that are necessary to achieve the purpose and structure of the genre. For example, he used the passive form “it is believed that” to introduce the target prejudice, and the modal expression “should change” to give his position. He also organized his ideas using textual resources such as “firstly”, “secondly” and “thirdly” to present his three arguments in order, and “To conclude” to indicate the last stage of the essay. Manson’s use of these passive forms, modals and conjunctive resources is characteristic of the genre of expository essays (Derewianka & Jones, 2016).

Nevertheless, a closer look into each of the three arguments presented in the arguments stage reveals that Manson could have better developed them. In his first argument, he provides supporting ideas for women’s intellectual equality with men, claiming that they can become professionals and hold important positions in renowned companies, but not for their physical equality (see Argument 1 in Figure 2). Also, women’s capabilities highlighted in this first argument are related to a professional domain rather than to the traditionally masculine domain of politics to which Manson refers in the thesis stage, and which he wants to challenge in his essay.

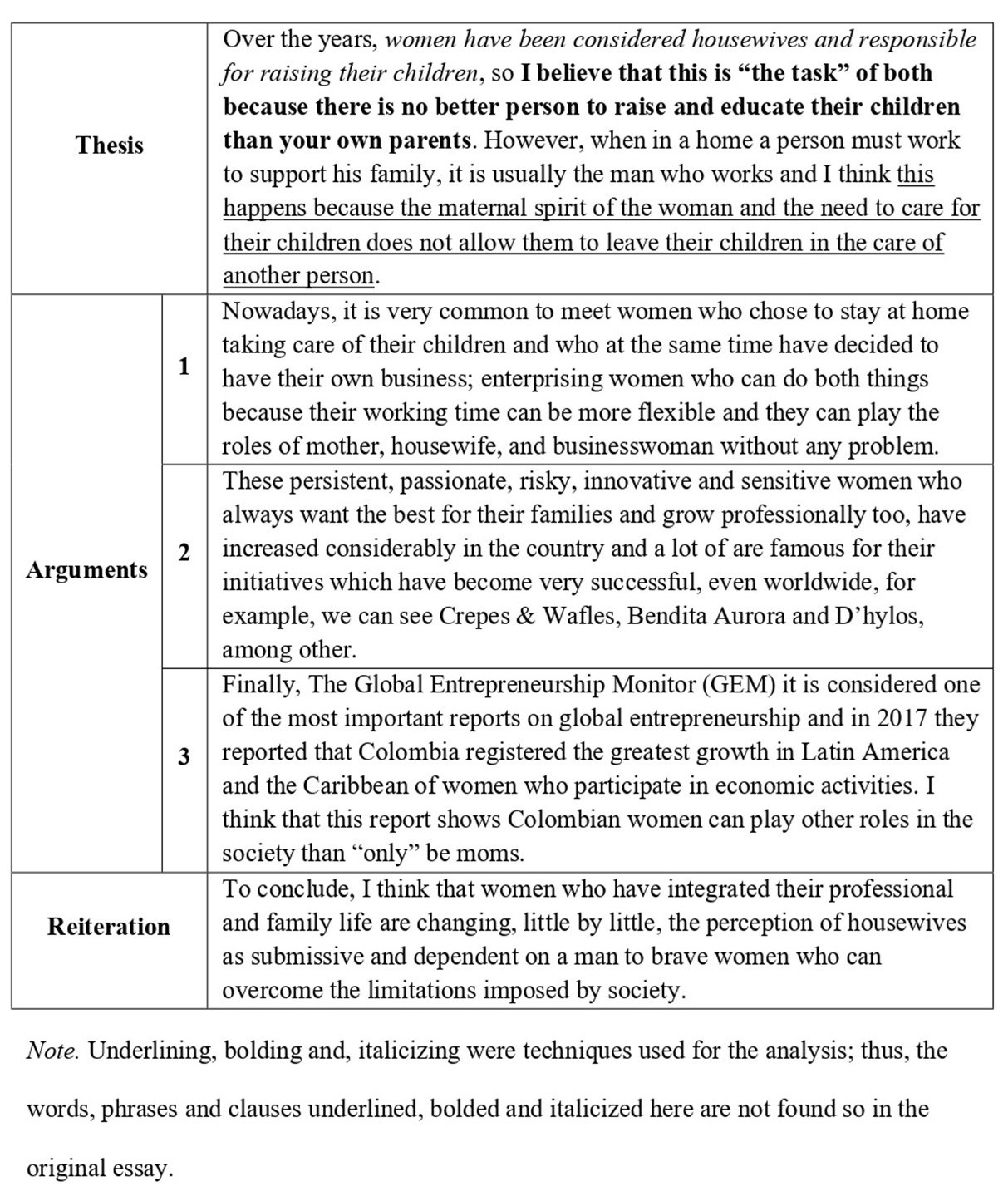

Similarly, other students, who wrote longer essays than that of Manson’s and used a wider variety of sentence types and lexical choices, also demonstrated difficulties in structuring their essays. For example, although Isabella had a relatively high English level and tried to comply with the stages of the genre, she still struggled to structure her essay cohesively. As seen in Figure 3, the thesis, arguments and reiteration stages can be identified in Isabella’s essay:

In the thesis stages, Isabella introduces the target prejudice, women merely seen as housewives and caregivers (see sentence in italics), and then presents her thesis: the idea that raising children is a task for both parents and not exclusively for women (see sentence in bold). However, in the second sentence of this stage, Isabella accounts for the traditional roles of women as caregivers of children and men as providers, enhancing women’s maternal spirit (see the underlined clause), rather than contesting them. In addition, her three arguments in the arguments stage enhance women’s contribution to their family economy, their roles as mothers and housewives, and their entrepreneurial capabilities. Although these arguments support her position on women’s capacity to be more than housewives and caregivers of children, they do not develop the idea of parents’ shared responsibility for their children’s education, as outlined in her initial thesis. In the reiteration stage, instead of restating her thesis, Isabella reiterates the idea developed in the arguments stage.

Finally, the participants also perceived the unit as a significant contribution to helping them improve their understanding of the genre of expository essays. For example, when interviewed at the end of the implementation, Logan said, “honestly, I was not sure about how to do it. So, in addition to learning from doing the research and writing the essay, I was able to retake on my previous knowledge” (Logan’s interview). Similarly, Mia stated that the process for writing an essay during the unit was different to her previous experiences since she “had previously learnt about writing essays but in a very different way, not with a focus on the arguments”, and it was also helpful because it was often difficult for her to make her “point of view clear and in an organized way” (Mia’s interview).

Overall, most students gained access to the genre of expository essays, particularly in English, as they became more familiar with its purpose and general structure, compared to their previous experience with the genre. Notwithstanding this gain, it is necessary for students to be given further opportunities to engage with the genre, deconstructing more complex models of expository essays, paying attention to how these are logically structured through different language resources, so that students can overcome their difficulties and gain greater control of the genre (Derewianka & Jones, 2016).

Valuing Students’ Diverse Beliefs, Experiences and Backgrounds (Diversity)

According to Janks (2010), teachers should value their students’ diverse ways of thinking, saying, doing, reading and writing the world. Hence, they should be aware and take advantage of the fact that, when coming into the classroom, students already carry different beliefs and values, have been exposed to different discourses, have previously consumed several texts for varied purposes, and have received an education that privileges different kinds of knowledge (Janks et al., 2014). These differences account for human diversity, that is, the heterogeneous ways in which we construct and experience the world (Janks et al., 2014).

The data collected in this study showed that the participating students were able to express different viewpoints from their diverse personal experiences, characteristics and backgrounds when discussing issues of gender stereotyping. This could be seen in students’ answers to the question about the roles of women in society presented in the first worksheet in which, while most of them considered women as equally capable as men in academic and professional areas, two students highlighted more traditionally expected qualities of women, such as being delicate, charisma, friendliness and being caring, as key characteristics of their social roles. For instance, Lucas stated that “women with their charisma contribute to a society. The delicate and friendly part in all its disciplines” (Lucas, worksheet 1). Similarly, Sophia highlighted the importance of women in healthcare occupations, especially nursing, since “they always have curative abilities for her delicacy [sic]” (Sophia, worksheet 1).

Students’ essays provided further evidence of these differing perspectives. Table 3 summarizes the gender prejudices students targeted in their essays and the positions they took.

Table 3 Sunlillary’ of Gender Prejudices Targeted in Students Essays

| Target gender prejudice | Student | Position |

|---|---|---|

| Women are supposed to cook and do housework | Emma | Against |

| Liam | Against | |

| William | Against | |

| Women are not politicians | James | Against |

| Oliver | Against | |

| Women are not as strong as men | Lucas | Against |

| Olivia | ‘Yes, but...’ | |

| Women are supposed to make less money than men | Benjamin | Against |

| Logan | Against | |

| The best women are stay at home moms | Manson | Against |

| Noah | Against | |

| Women have to be delicate, sweet and maternal | Mia | Against |

| Women are responsible for raising their children | Isabella | ‘Yes, but...’ |

| Women’s discrimination in sport | Sophia | Against |

As can be seen in Table 3, although most students took a clear stance against the chosen target prejudices, two students, Olivia and Isabella, presented a more cautious ‘Yes, but…’ position. For instance, Olivia’s ‘Yes, but…’ position towards the prejudice ‘Women are not as strong as men’ targeted in her essay is expressed in her thesis that men may be physically stronger than women, but women may be emotionally stronger than men. To support this position, she first provides two definitions of ‘force’ from the Oxford Dictionary as can be seen in the following excerpt:

Oxford Dictionaries defines this word (force), first as "The quality or state of being physically strong", and second as "A person or thing perceived as a source of mental or emotional support". (Olivia’s essay)

Then Olivia uses these two meanings to develop her arguments throughout her essay as shown in Table 4.

Table 4 Physical and Emotional Force in Olivia’s Essay

| Force as being physically strong | Force as being emotionally strong |

|---|---|

| Physically men have more strength than women | There is also mental, emotional and willpower and in that, women have shown that they are very good |

| Women have more muscular strength for tasks related to flexibility, coordination and balance | Women have greater capacity to resist great pressures in their work |

| Women can also endure pain as strong as childbirth | (Women have greater capacity) to support other people, their bosses and hard work |

| Willpower also allow them (women) to be able to care for their children in the disease | |

| (Willpower also allow women to) get ahead when you have difficulties of a sentimental, work and health. |

Note. This table shows excerpts selected from Olivia’s essay in relation to physical and emotional force. Bolded and underlined words were used for the analysis, and words in parenthesis provide clarification; thus, they do not appear so in the original essay.

In terms of physical strength, it can be seen how Olivia recognizes that men are stronger than women, but then counterbalances this argument with the idea that women can be more muscularly suitable than men for tasks requiring flexibility, coordination and balance. Regarding emotional strength, she highlights women’s endurance, tolerance, supportiveness, and willpower. Moreover, Olivia emphasizes human diversity not only in terms of gender differences, but also in terms of individual differences that makes us unique, stating that there are strong and weak men, and women who are more resilient than others. To conclude, she asserts that both forces, physical and mental, are necessary for the survival of the species, but then poses the question “when people are physically strong and fail at something…which force is more important, mental or physical?” (Olivia’s essay).

Similarly, Isabella’s ‘Yes, but…’ position towards the prejudice ‘Women are responsible for raising their children’ also proved to be a nuanced position. Although she agrees that it is usually men who must work as women stay home because “the maternal spirit of the woman and the need to care for their children does not allow them to leave their children in the care of another person” (Isabella’s essay), she states that the task of raising children must be carried out equally by men and women. In the rest of her essay, however, Isabella focuses on underscoring women’s capacity to play both roles as providers and nurturers, which demonstrates her agreement with the notion that women must raise their children, but does not develop the idea of women and men’s shared responsibility for child-rearing.

Furthermore, to hold their positions towards the target prejudices, students drew a variety of resources into their essays, such as their personal experiences, their knowledge of the tradition, and foreign and local examples. Regarding personal experiences, for example, in her essay, Emma describes the gender roles she perceived in her family when she was a child and her husband’s current gender bias. She introduces this personal experience to claim that she totally disagrees with such gender stereotyping that favors men over women.

Concerning their knowledge of the traditional beliefs of their own context, seven students used this knowledge to frame their ideas about the gender prejudices targeted in their essays. Table 5 summarizes such knowledge.

Table 5 Students’ Knowledge of their Inherited Tradition

| Student | Knowledge of the tradition |

|---|---|

| James | They (women) hadn’t a fundamental role in the time of our grandparents this time was characterized by having a male chauvinist culture about women, where they believed that the only duties of women were look after of the house, look after of the children and look after their husbands. |

| Sophia | In the past it was more common to hear and see that the role of women was limited only to assume their role as mother and wife and perform housework |

| Mia | From generation to generation, society has a model of how women should behave, however, with the change of time, the advances in culture and new ideologies, this model hasn’t presented many differences |

| Logan | if you compare the times in the past the women were less possibilities than men, because they could not study and only engaged to housework |

| Manson | The political tradition always has had as the only protagonist the man leaving aside the participation of the woman |

| Oliver | We are in a world in which there has always been chovenism towards women, society has had a wrong thinking, a wrong vision, which for ages past placated women |

| Noah | All of us have been raised under this thought, parents always say to their sons to look for a good girl and to their daughters to be a good girl, which means a girl who never stays out late, a girl that never drinks or smokes |

It can be seen in Table 5 that students understand the cultural tradition they have inherited from parents and grandparents as one that is male-dominated in which women are submissive to their husbands and their roles limited to housework. This awareness of their cultural reality serves as students’ starting point for advancing their positions and arguments against gender prejudices.

As to including examples which highlight women’s value, four students mentioned successful women in sports, business, and politics. Table 6 summarizes such examples.

Table 6 Examples of Successful Women Included in Students’ Essays

| Student | Example used | Domain |

|---|---|---|

| Olivia | In Colombia there are incredibly strong women physically in sports such as Ma Isabel Urrutia, Caterine Ibargüen, Sofia Gomez, etc. | Sports |

| Isabella | even worldwide, for example, we can see Crepes & Wafles, Bendita Aurora and D'hylos, amoung other. | Business |

| Logan | is the example of: Oprah Winfrey, Madame CJ Walker, Cher Wang who used all their abilities to promote their companies and at the moment they are multimillionaires. | Business |

| Manson | In the past presidential elections in Colombia, four candidates had four women as their vice presidential formula. | Politics |

| Thirdly, worldwide women have won presidential elections in first world countries, with solid economies, including Angela Merkel, president of Germany, country that is part of G8, the eight richest countries in the world, Dilma Rousseff president of brazil, the economy biggest in South America. |

These examples of women who have been recognized locally and internationally as being successful within the traditionally male-dominated areas of sports, business and politics are used in students’ essays to prove women’s capacity to succeed in such potentially discriminating domains.

All this suggests that, although students may share social, economic and educational backgrounds, they will display different ways of thinking, feeling and valuing the world, rooted in their individual life experiences. Hence, teachers should value their students’ diverse ways of thinking, saying, doing, reading, and writing the world, as well as help them examine how social identities are formed and organized to form different relations of power (Janks, 2010).

Enhancing Students’ Agency to Challenge Common Gender Stereotypes (Design)

Janks (2010) states that developing students’ critical literacy goes beyond helping them deconstruct dominant discourses, and moves into empowering them to challenge and change such discourses. Hence, students need to develop their ability to use a wide range of meaning-making resources to enhance their agency, enabling them to position themselves and their audience, thus transforming the discourses they have deconstructed (Janks et al., 2014). Data in this study suggest that students were not only able to develop a deeper awareness of the unequal power relations portrayed in common gender stereotypes, but also write expository essays in which they expressed their critical stance towards this issue, using a significantly varied range of language resources.

For instance, in his essay, Oliver deployed several language resources to challenge the traditional belief that “the best women are stay-at-home moms”, stating that society has been wrong regarding this issue, and supporting women’s struggles to be set free from this kind of prejudice.

In the first instance the world has been evolving, previously it was believed that the woman only had to devote herself to housework, to have and raise children and fulfill their marital functions. (Oliver’s Essay)

In this excerpt, it can be seen how Oliver chooses language devices to deem the prejudice “the best women are stay-at-home moms” an outmoded idea. Among such devices, he uses the present perfect continuous form of the verb evolve, in the clause “the world has been evolving”, to emphasize that human societies worldwide have changed, and continue changing, their behavior, values and beliefs, including those around gender stereotypes. He also uses the adverb previously together with the past passive form it was believed, implying that the traditionally rooted idea that “the best women are stay-at-home moms” may have been considered acceptable in the past but not today. In so doing, Oliver subtly challenges his audience to re-evaluate the relevance of traditional female stereotypes considering present-day social realities.

Additionally, throughout his essay, Oliver highlights women’s capability to stand up against gender inequalities, describing women as determined, strong and courageous. To support this position, he makes a series of seven statements about women throughout his essay, which are shown in Table 7.

Table 7 Statements about Women in Oliver’s Essay

| # | Statements |

|---|---|

| 1 | "women are a representation of strength and courage" |

| 2 | "the women got tired of being mistreated, of not being valued" |

| 3 | "they (women) decided to undertake a long and extensive struggle to be liberated" |

| 4 | "the woman was a slave who had to fight against adversity to break free" |

| 5 | "it was not easy (for women) to undertake this fight but nevertheless they left the fear and they did it" |

| 6 | "the woman is so valuable that gives up the last breath for the protection of their children" |

| 7 | "women are the strongest and most responsible" |

Note. This table contains a list of statements taken from Oliver’s essay. This was done to facilitate the analysis of lexical resources.

These statements show Oliver’s choice of language devices to support his position, including noun groups such as a representation of strength and courage (1), a long and extensive struggle to be liberated (3), a slave (4), this fight and the fear (5), the last breath (6), and the strongest (7). He also uses the verb groups got tired of being mistreated and (got tired) of not being valued (2), decided to undertake (3), had to fight (4), to undertake, left and did (5), and gives up (6), as well as the prepositional phrases against adversity to break free (4) and for the protection of their children (6). In these resources we can identify at least four interconnected lexical chains as shown in Table 8.

Table 8 Lexical Chains in Oliver’s Essay

| Inequalities | Determination | Strength | Courage |

|---|---|---|---|

| being mistreated (2) not being valued (2) slave (4) adversity (4) fear (5) | got tired (2) decided to undertake (3) undertake (5) left (5) did (5) gives up (6) | strength (1) protection (6) strongest (7) | courage (1) struggle (3) to be liberated (3) to fight (4) to break free (4) fight (5) the last breath (6) |

Note. This table contains semantically related noun and verb groups identified in Oliver's statements included in Table 7. The numbers in front of each group refers to the number of the statement in Table 7.

The lexical chain of inequalities contains words depicting an unfavorable situation for women, implying mistreatment, disparagement and slavery. The second chain, determination, includes behaviors and actions women have taken to stand up against such an indignant situation. The third and fourth lexical chains, strength and courage, highlight the personal characteristics necessary for women to undertake such a fight. In so doing, Oliver not only exploits lexical resources in his essay, but also attempts to raise empathy in his audience towards the cause of women’s liberation. Indeed, during the interview, he stated that writing an essay on gender stereotyping helped him pay attention to such an important issue, grow personally, express his ideas, and potentially contribute to the solution, as well as improve his writing skills (Oliver’s interview).

Nevertheless, not all the students succeeded as Oliver did in using varied lexical resources to position themselves and their audience. For example, Lucas wrote a rather brief text in which, although he used language choices such as “In my opinion”, “you should treat” (twice), and “I think that” to state his position, he used unvaried lexical resources (see Table 9) to develop his arguments and position his audience more effectively.

Table 9 Lexical Chains in Lucas Essay

| Equality | Strength | Female reproduction |

|---|---|---|

| equality (3 times) | Physical and emotional strength | the ones who give us life |

| their natural strength for that (giving birth) | to ovulate | |

| the necessary strength to ovulate | to produce thousands of gametes | |

| without showing how strong we are |

Table 9 shows the three lexical chains of equality, strength and female reproduction that unfold in Lucas’ essay to convey the message that women should be treated as equals to men since they are also strong due to their natural reproductive capabilities. However, his development of each lexical chain and their interconnection remains incipient. To construct the lexical chains of equality and strength, Lucas mainly used repetition: the nouns “equality” and “strength” are used three times each. He also used the adjectives “same'', semantically related to equality, and “strong”, in relation to strength. Lucas’ use of these resources is not enough to develop the idea of what he means by “equality”, nor to distinguish between physical or emotional strength, or whether he focuses on one or the other.

In the lexical chain of female reproduction, Lucas highlighted women’s reproductive capability as a salient female strength, using the noun group “the ones who give us life”, and even introducing the technical terms “to ovulate” and “gametes”. However, although women’s reproductive capability seems to be Lucas’ main argument to support his position, he failed to elaborate on it. Lucas’ scant use of lexical resources might be explained not only by the limited time students had to work on their essays, but also by the fact that further scaffolding was needed. Had Lucas had the time and the support to exploit these lexical chains further, he would have written a more focused, organized and detailed expository essay.

As presented in this section, students were able to write expository essays to express their critical stance towards stereotypes of women, using a variety of English language resources. This is an important step in developing students’ critical literacy as they need to improve their ability to use various meaning-making resources that enable them to contest and change dominant discourses in their society (Janks, 2010).

CONCLUSIONS

This qualitative study aimed to explore the effects of implementing an instructional unit designed following Janks’ synthesis model of critical literacy to help a group of university EFL students develop critical literacy. Overall, findings suggest that the intervantion helped students unveil issues of power related to stereotypes of women as portrayed in TV commercials (power), gain access to the genre of expository essays (access), express their different viewpoints from their diverse personal experiences, characteristics, and backgrounds (diversity), and use a variety of English meaning-making resources in their expository essays to take a stance and challenge several gender-based stereotypes (design).

In terms power, it was an important gain for students to become aware of how gender stereotypes associated with men and women’s roles in society are perpetuated in everyday discourses, such as TV commercials, since such awareness enables them to challenge and reject existing gender inequalities in their own communities, thus contributing to social transformation (Hayik, 2015). This was possible by bringing into class students’ personal experiences and knowledge of their social contexts as a resource to engage in critical reflections and discussions about unequal power relations between men and women as portrayed in a variety of texts (Hayik, 2015; Sultan et al., 2017).

As for gaining access to powerful genres, it was significant for students to deepen their understanding of the purpose, structure, and language of expository essays since this not only enabled them to state and support their opinions on common gender stereotypes, but also complied with the characteristics of a genre highly valued in academic contexts. Alford and Jetnikoff (2016) underline the importance of helping students gain control of such genres, as well as understanding the power embedded in the linguistic and other semiotic choices such texts make in constructing representations of the world. It is also significant for second language learners to gain greater access to a genre that might be challenging for them (Schleppegrell, 2004).

Regarding diversity, it was important for students to compare female stereotypes as presented in TV commercials with their own beliefs and explore this social issue from multiple perspectives. In doing so, they had the opportunity to approach gender stereotyping from their different experiences, individual characteristics, and cultural backgrounds, thus raising their diverse voices and taking their own position towards stereotypes of women as they acknowledge others’ positions. Exploring the issue of gender stereotyping while drawing on their own beliefs, experiences, and perspectives not only helps students gain awareness of how some social identities, such as gender, are privileged while others are marginalized, but also help them value their own ways of thinking, saying, doing, reading, and writing the world.

In terms of design, using a wide range of meaning-making resources to write expository essays that challenge and shift existing discourses on gender stereotyping was a significant gain for students. When encouraged to analyze texts that may carry potentially problematic issues, such as gender stereotyping, and then create their own texts using several language resources to dispute dominant discourses, students are granted opportunities to contest social practices that disempower some social groups in favor of others, and fight for fairness and equality (Hayik, 2015). Hence, it is important for students to use English resources to produce texts that help them position themselves and their readers as they dispute and transform existing discourses such as stereotypes of women (Janks, 2010).

Finally, this study has raised some implications for teaching and research. For EFL teachers interested in helping their students develop critical literacy, it is important to engage students in examining ideologies embedded in everyday and academic texts, helping them gain control of textual genres, and promoting understanding of the different ways of being in the world. Regarding research, although this study has shown the potential benefits of implementing Janks’ critical literacy model in the EFL classroom, further research is needed to explore the development of critical literacy of students with other proficiency levels, delve into the exploration of other social issues, and inquire about the preferences of students when responding using multimodal texts.