Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Desarrollo y Sociedad

Print version ISSN 0120-3584

Desarro. soc. no.68 Bogotá July/Dec. 2011

Railroads in Peru: How Important Were They?

Ferrocarriles en el Perú: ¿Qué tan importantes fueron?

Luis Felipe Zegarra*

* Luis Felipe Zegarra is PhD in Economics of University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA). He is currently Professor of Economics of CENTRUM Católica, the Business School of Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú (PUCP). Contact to lfzegarrab@pucp.edu.pe. The author thanks the assistance of the staff of the National Library of Peru, the Central Library of PUCP and the Instituto Riva Aguero-PUCP.

This paper was received September 28, 2011, modified October 5, 2011 and finally accepted October 28, 2011.

Abstract

This paper analyzes the evolution and main features of the railway system of Peru in the 19th and early 20th centuries. From mid-19th century railroads were considered a promise for achieving progress. Several railroads were then built in Peru, especially in 1850-75 and in 1910-30. With the construction of railroads, Peruvians saved time in travelling and carrying freight. The faster service of railroads did not necessarily come at the cost of higher passenger fares and freight rates. Fares and rates were lower for railroads than for mules, especially for long distances. However, for some routes (especially for short distances with many curves), the traditional system of llamas remained as the lowest pecuniary cost (but also slowest) mode of transportation.

Key words: Transportation, railroads, Peru, Latin America.

JEL classification: N70, N76, R40.

Resumen

Este artículo analiza la evolución y las principales características del sistema ferroviario durante el siglo diecinueve y principios del siglo veinte. Desde mediados del siglo diecinueve, los ferrocarriles fueron considerados una promesa para alcanzar el progreso económico. Varios ferrocarriles fueron entonces construidos en el Perú, especialmente en 1850-1875 y en 1910-1930. Con la construcción de los ferrocarriles, los peruanos ahorraron tiempo en sus viajes y en envíos de carga. El servicio más rápido de transporte no se produjo necesariamente al costo de mayores tarifas para los pasajeros y para carga. Las tarifas para pasajeros y para carga fueron menores para los ferrocarriles que para las de las mulas, especialmente para distancias largas. Sin embargo, para algunas rutas (especialmente para rutas cortas con muchas curvas), el sistema tradicional de llamas se mantuvo como el sistema de transporte de menor costo (aunque más lento).

Palabras clave: transporte, ferrocarriles, Perú, América Latina.

Clasificación JEL: N70, N76, R40.

Introduction

One important concern of the literature on economic history in the recent decades has been the impact of railroads on transportation costs1. In a seminal paper, Fogel (1964) indicated that in the United States railroads did not have a large impact on transportation costs; because this country had a system of navigable rivers and canals, which tended to provide fast and low-cost transportation for long distances. According to Fogel, "waterways and railroads were good, but not perfect, substitutes for each other ... The crux of the transportation revolution of the nineteenth century was the substitution of low-cost water and railroad transportation for high-cost wagon transportation. This substitution was made possible by a dense network of waterways and railroads ... Railroads were indispensable, however, in regions where waterways were not a feasible alternative ..."2 A system of rivers, canals and coastal routes were also available in most of Europe. In France, for example, rivers and canals were used, granting cheaper transportation than wagons. In Scotland, waterways included the sea routes, canals and rivers. Waterways also provided cheaper transportation than wagons3.

On the other hand, some studies indicate that the impact of railroads on transportation costs in some Latin America was large. Unlike the United States and Europe, Mexico and Brazil did not have navigable rivers in the habitable areas. In the case of Brazil most waterways in habitable regions were not navigable. Summerhill (2005) indicates that to exploit and commercialize the interior meant that freight had to travel over Brazil´s coastal mountain range o the backs of mules, or at best on wagons or carts. This system of transportation was costly. In these circumstances, the construction of railroads had a large impact on transportation costs. Similarly, in the case of Mexico, Coatsworth (1979) indicates that "except for local freight across three large lakes near highland population centers and short hauls up several rivers from the Gulf to the base of the mountains, internal water transport was unknown"4. Also, considering that most Mexicans lived far from the two coasts, coastal shipping did not play the same role as it did in the United States and in Europe. Most transportation in Mexico was then conducted by wagons and mules. In these circumstances, the construction of railroads led to a large reduction in transportation costs. On the other hand, in the case of Colombia navigable rivers facilitated transportation and the impact of railroads on transport costs was lower than in Brazil and Mexico. As Mc.Greevey (1989) indicates, due to the improvement in fluvial transportation in the 19th century, the regions located near navigable rivers were linked to foreign markets. For other regions, however, mules remained as the main mode of transportation5.

This study analyzes the main features of the railway system of Peru, and its impact on transportation costs6. By 1930 Peru had railroads in the coast and the highlands. Prior to the construction of railroads, much of transportation in Peru was conducted by narrow roads on the backs of animals, or by ship along the coast. Several important politicians and businessmen supported the construction of railroads. Railroads represented in the minds of many the path to progress in Peru. In fact, railroads provided a fast service of transportation, which reduced time costs for passengers and sped up communications. However, railroads were not necessarily cheaper than other modes of transportation. Llamas, widely used for transportation of freight in the Andes, could be cheaper than railroads.

Geography imposed several obstacles to transportation. In many parts of the coast, the terrain was sandy, which made the traction of wheel extremely difficult. Travelling through the coast could be very dangerous. As Tschudi (1847) indicates, "... The roads lead through plains of sand, where often not a trace of vegetation is to be seen, or a drop of water to be found for twenty or thirty miles. It is found desirable to take all possible advantage of the night, in order to escape the scorching rays of a tropical sun; but when there is no moonlight, and above all, when clouds of mist obscure the directing stars, the traveler runs the risk of getting out of his course, and at daybreak, discovering his error, he may have to retrace his weary way. This extra fatigue may possibly disable his horse, so that the animal cannot proceed further. In such an emergency a traveler finds his life in jeopardy; for should he attempt to go forward on foot he may, in all probability, fall a sacrifice to fatigue and thirst ..." 7.

In the highlands, the terrain also represented an obstacle for transportation. Narrow roads, deep canyons, and long and steep ascents made transportation very difficult. In a travel into the highlands of Peru, Wortley (1851) indicated that "... the elevated plateau and table-lands, separated by deeply-embosomed valleys, and the gigantic mountains that intervene between the coast and the table-land, render travelling tedious and difficult. Roads and bridges, in many parts, are entirely wanting; and in places where rude and scarcely-distinguishable paths are found, they lie along the perilous edges of overhanging and rugged precipices, perpendicularly steep; and these tracks, moreover, are almost always so dangerously narrow, that the sure-footed mule can alone tread them with any security ..."8.

Waterways were usually a cheaper mode of transportation than roads. However, rivers were not navigable in the coast and highlands of Peru. The Pacific Ocean constituted a faster and cheaper mode of transportation than overland transportation, especially after the invention of the steam machine. However, its use was naturally constrained to coastal towns. Also, port infrastructure was inadequate, which led to high port costs, making navigation costly for short routes9.

In these circumstances, the construction of railroads had the potential to reduce transportation costs. In the mid-19th century, the construction of railroads was considered promising by Peruvians. Several argued that Peru would be able to take advantage of its great endowments of natural resources (mining resources and land) with the introduction of the railroad. In the 1850s, Ernest Malinowski argued that with reliable rapid transportation, Peruvians "should be able to compete with analogous goods from other countries. And not just in foreign markets, but even in this country, as wheat, coffee, cacao, and so on prove, which for the coastal consumer now come largely from abroad -even when interior growers can supply them in sufficient quantity, even superior quality"10. Later in 1860, Manuel Pardo indicated that the construction of railroads would reduce transportation costs dramatically, allowing the exploitation of natural resources, especially in the central highlands11. According to Pardo, "if the locomotive, in other countries, facilitated production and commerce, in ours its mission is much higher: to create what today does not exist; to fertilize and give life to the elements of wealth, which today lie in an embryonic, latent state"12. In the following decades, several millions of dollars were invested in rail construction13. The total railway track increased from only 15 kilometers in 1855 to 1,113 kilometers in 187514. By 1930 the railway system of Peru had more than 2,800 miles.

The structure of the paper is as follows. Section I discusses the construction and nature of railroads in Peru until 1930. Section II describes the optimism of politicians and businessmen about the impact of railroads. Section III discusses the time savings due to the construction of railroads. Section IV analyzes the differences in passenger fares and freight rates between railroads and other modes of transportation. Section V compares the freight rates of Peru and other countries. Section VI concludes the paper.

I. The railroad system of Peru: evolution and main features

With the invention of the steam machine, many countries entered into a period of railroad construction. Peru was the first country that built railroads in South America. The first railroad of Peru was built in 1849. This railroad connected the capital city of Peru and Callao, the main port of Peru. The second railroad of Peru was Tacna-Arica, built in 1856. Other railroads were built in the 1860s and 1870s. By 1877 Peru had 1,261 miles of railroads. The War of the Pacific (1879-83), in which Chile defeated Peru and Bolivia, affected the construction of railroads. During the war some railroads were destroyed. In addition, Peru lost the Railroad of Tarapaca (as the province of Tarapaca became part of Chile). Railroad length then declined from 1,261 million miles in 1877 to 937 miles in 1883. Furthermore, economic stagnation and the decline in fiscal revenues in the post-war period affected railroad construction. By 1900 the railway net was only 1,118 miles, below pre-war levels. In the early 20th century new railroads were built. The length of the railway net increased to 1,861 miles in 1910, 2,242 miles in 1920 and 2,810 miles in 1930 (Figure 1).

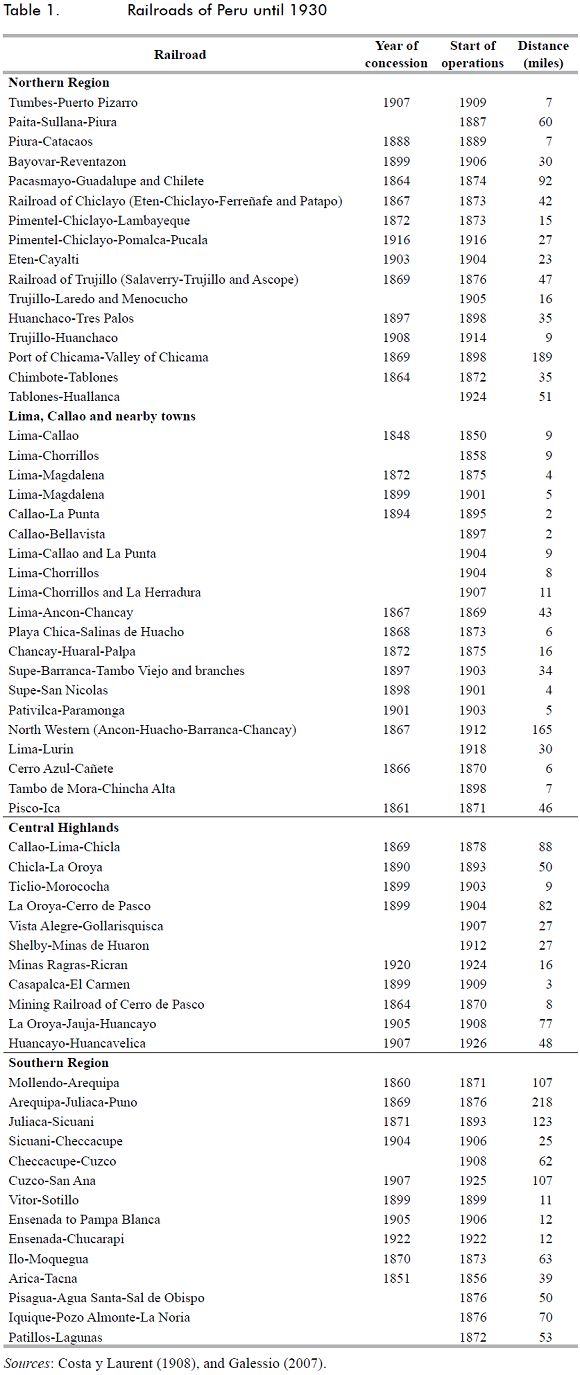

Table 1 lists the railroads built in Peru from 1840 to 1930 and Figure 2 depicts the map of railway network in 1939. One of the largest railroads was the Central Railway. This railroad connected the port of Callao with the city of Lima and several towns in the central highlands. The Central Railway was formed by the railroads of Callao-Lima-La Oroya, La Oroya-Cerro de Pasco, La Oroya-Huancayo, Ticlio-Morococha, and others that connected the main railroad of Callao-La Oroya with mining centers in Junin. The construction of the railroad Callao-La Oroya started in 1869. However, it took a long time before the construction ended. By 1878 this railroad arrived from Callao to Chicla (87 miles). The War of the Pacific paralyzed the construction. Then the railroad arrived to Casapalca in 1892 and La Oroya in 1893. This railway reached high altitudes: Casapalca was located to 4,147 meters of altitude in the Andes. Later other lines were built. The line Ticlio-Morococha was built in 1900 and the railroad La Oroya-Cerro de Pasco was built in 1904. Then other railroads connected La Oroya and Huancayo in 1908 and Huancayo and Huancavelica in 1926.

Another important railway system was built in the South; this system was formed by the railroads Mollendo-Arequipa, Arequipa-Puno and Juliaca-Cuzco. The railroad of Mollendo-Arequipa connected the port of Mollendo and the highlands of the department of Arequipa, reaching the city of Arequipa in the highlands at 2.301 meters of altitude. A new line was constructed from Arequipa to Puno in 1871. This railroad reached its highest altitude on Crucero Alto at 4,470 meters of altitude, going then down to Juliaca and Puno, two important cities in the department of Puno. A new line that departed from Juliaca to Sicuani was built in 1891. This railroad was then extended to Checcacupe in 1906 and to the city of Cuzco in 1908. Also in Cuzco was constructed the railroad Cuzco-Santa Ana in 1925. Other railroads were built in Arequipa to transport products from nearby haciendas15.

In the North of Peru, several railroads were also built, connecting the main cities and ports. The railroad of Eten was built in 1871, connecting the Northern port of Eten with the towns of Monsefú, Chiclayo, Lambayeque and Ferreñafe. Also in 1871 was built the line Chiclayo-Patapo, connecting the city of Chiclayo, the Northern haciendas of Pomalca and Tuman, and the mills of Dall´Orso, Santa Isabel, La Union and Mocce in the department of Lambayeque. In 1873 it was built the railroad Chiclayo-Pimentel, connecting Chiclayo with the port of Pimentel. Three years later a new railroad was constructed: the railroad of Pacasmayo connected the sea port of Pacasmayo, San Pedro and Calasñique16. Several years later, in 1904, a new railroad was built in the department of Lambayeque, connecting the port of Eten with the hacienda Cayalti, in order to facilitate the transportation of products from this hacienda. This was the objective of the Aspillaga family, owner of hacienda Cayalti. In the department of La Libertad several railroads were built to facilitate the transportation of products from haciendas in the valleys of Chicama and Santa Catalina to the main ports in the region. One railroad was built in 1875, connecting the port of Salaverry, Trujillo (the capital city of La Libertad), the rich sugar valleys of Chicama and Santa Catalina, and the town of Ascope. Other railroads were then built by the private sector17.

In the province of Lima, several railroads were also built. The first railroad, built in 1849, connected Lima with the port of Callao. Later the railroad Lima-Chorrillos was built in 1858; this railroad connected the city of Lima and the town of Chorrillos (located next to ocean to only 14 kilometers from Lima), passing through La Victoria, Miraflores and Barranco. The railroad Callao-Bellavista was built in 1897, in order to connect the deposits of wheat in Bellavista and the mill La Libertad in Callao. Another line was built in 1902, connecting the city of Lima and the town of Magdalena, located to five miles from Lima. In the North of the department of Lima, the railroad Lima-Ancon-Chancay was built in 1869, becoming the only railroad that ran parallel to the coast. This railroad connected the city of Lima, the beach town of Ancon and the valley of Chancay. However, the line Ancon-Chancay was destroyed by the Chilean Army during the War of the Pacific. From 1883 then the railroad only connected Lima and Ancon, located to 24 miles to the North of Lima18. Then in 1912 it was built the North Western Railroad which connected the town of Ancon with the towns of Huaral, Huacho, Chancay, Sayan and Barranca. Other railroads were also built to transport products from nearby haciendas to the city of Lima19.

Since most railroads did not run in parallel to the coast, they could not substitute ships as mode of transportation. In fact, railroads may have been complementary in transportation to steam and sailing navigation in the Pacific Ocean. For instance, to transport bulk from Lima to Chiclayo in the 1900s, the bulk was probably transported by railroad from Lima to Callao, then by ship to the port of Eten in the department of Lambayeque, then by railroad to Chiclayo. Similarly, to transport bulk from Lima to Arequipa, the bulk was probably transported to Callao by railroad, then to Mollendo by ship and then to the city of Arequipa by railroad. In addition, to travel from Lima to Piura, a person had to take a train to Callao, take a ship to the port of Paita, and finally a train to Piura.

The railway system was a partial substitute to the traditional system of overland transportation. In the coast, railroads were a substitute of mules; and in the highlands, railroads were a substitute of mules and llamas. The Central Railway replaced much of the traditional system of mules and llamas in transporting people and bulk from Lima to Junin. Similarly, the railroads in the South may have replaced the system of mules and llamas in transporting people and bulk between Mollendo, Arequipa, Puno and Cuzco.

Animal transportation, however, did not necessarily disappear: railroads only served a few number of routes. For most routes, then, the traditional system of transportation was a complement to railroads and ships. For instance, to travel from Pisco to Ayacucho, a person may have taken the railroad to travel from Pisco to Ica, and then it may have traveled by mule to Ayacucho. To transport bulk from Lima to Cajamarca, the bulk had to be taken to Callao by railroad, then by ship to Pacasmayo, then by railroad to Chilete and finally by mules to Cajamarca. To travel from Lima to Maldonado, one needed to take the railroad to Callao, then a ship to Mollendo, a train to Tirapata and then travel by mule to Puno.

A large number of towns were not connected by railroads. Dávalos y Lissón (1919) indicated that according to a study by the Engineer Tizón y Bueno, there were around 10,000 towns in Peru in the 1910s and that only 300 of them were connected by railroad in the late 1910s. Similarly, Milstead (1928) indicated that railroad infrastructure was very deficient not only in the highlands but also in the coast. According to Milstead, in the early 1920s primitive transportation facilities persisted in around 85% of the country. Only 2,018 miles of steam railroads and 100 miles of street and interurban lines were in operation in 1924. Although some railways had been constructed from the 1850s, there was no an integrated railway net: "... most of the railways consist of short isolated lines of varying gauges connecting an ocean port with the chief towns and plantations of the adjacent irrigated valleys". In addition, there was no longitudinal railway that connected the coastal valleys. Moreover, only two systems (the Central Railway and the Southern railroads) connected the coast and the highlands. Most highland and jungle towns largely depended on the traditional system of mules and llamas20.

Peru was far behind many countries in Latin America. By 1913 Peru only had 0.4 miles of railway track per 1,000 inhabitants, below the Latin American average of 0.9 miles per 1,000 inhabitants (Figure 3). Peru was far behind Argentina, which had 2.7 miles per 1,000 inhabitants, around seven times as much as did Peru. Other countries with a clear lead over Peru were Chile, Costa Rica, Mexico, and Uruguay. All of these countries had more than one mile per 1,000 inhabitants. Other countries with more railway length per-capita than Peru were Brazil, Cuba, Dominical Republic and Panama. In South America, Peru only performed better than Colombia, Ecuador and Venezuela.

II. Railroads and the hope for economic progress

From the mid-19th century, railroads represented in the minds of many businessmen and politicians the path to economic progress. The first advocate of railroad building was perhaps Ernest Malinowski, the Engineer in charge of building the Central Railway, who in the 1850s argued that with reliable rapid transportation, Peruvians "should be able to compete with analogous goods from other countries. And not just in foreign markets, but even in this country, as wheat, coffee, cacao, and so on prove, which for the coastal consumer now come largely from abroad -even when interior growers can supply them in sufficient quantity, even superior quality". Another supporter of railroad building was Manuel Pardo, a businessman and President of Peru between 1868 and 187221. In his Estudios de la Provincia de Jauja, published in 1860, Pardo indicated that the construction of railroads would reduce transportation costs dramatically, allowing the exploitation of natural resources, especially in the central highlands22. "If the locomotive, in other countries, facilitated production and commerce, in ours its mission is much higher: to create what today does not exist; to fertilize and give life to the elements of wealth, which today lie in an embryonic, latent state"23. Pardo envisioned a railroad that connected the rich valley of Jauja in the department of Junin to the city of Lima24. Building such railroad would place Junin´s grains, livestock and minerals to only four or five hours of the capital of the republic25.

The support for railroads was not limited to the central region of Peru. In Arequipa, several businessmen also supported the construction of railroads. In particular, in the document Ferrocarril de Arequipa, Patricio Gibbons and Joseph Pickering indicated that the railroad of Arequipa, which linked the Pacific seaboard and the departments of Arequipa and Puno, would bring economic diversity to the Southern region. In a public letter sent in 1869 by the Prefect Antonio Rodríguez to the Ministry of Government, Police and Public Works, Prefect Rodríguez wrote that the people of Arequipa was grateful for the construction of the railroad Arequipa-Puno, which would benefit the departments in the South. The industrial life of the region would be more powerful, the citizen would know the advantages of working, and moreover the internal wars would soon end26.

The boom in the construction of railroads occurred between 1868 and 1872, during the government of José Balta, a deep believer in the benefits of railroads. According to historian Fredrick Pike, "Balta in particular came to believe that by criss-crossing Peru with railroads, the full economic potentialities of so richly-endowed a country could be readily realized, while at the same time anarchy and revolutionary activity would be stamped out"27. The legislation usually referred to railroads as crucial for exploiting our natural resources, substituting imports for domestic production, and bringing prosperity to our country. The general law about construction of railroads and issue of bonds, passed in 1868, indicated that it was Congress´ obligation to facilitate the communication between populated areas by promoting the construction of railroads all over the Peruvian territory28. Similarly, the concession-law of the railroad of Pacasmayo indicated that roads were crucial to link the populated areas, providing comfortable exportation to their products and cheap purchase of imported goods, therefore developing agriculture, mining and industry, the only safe and stable sources of wealth; and that railroads constituted the best type of road to achieve those objectives29.

Railroads were considered as crucial for economic growth not only by Peruvians but also by foreigners. The U.S. citizen Charles Rand offered also an optimistic view on the Peruvian railroads30. In his Railroads of Peru, published in 1878, Rand indicated that railroads had produced positive benefits in the Peruvian economy. "Since the inauguration of the present Railroad system, yet incomplete," argued Rand, "the income of the nation has increased in a gradually augmented ratio, aside from the great indirect advantages bestowed upon the people, which cannot be disputed"31. The construction of railroads was "a wise measure of public policy"32, because railroads were needed for the development of immense resources of the country. Later in 1890, a British Vice-Consul looked at the future of Peru with optimism: "The prolongation of the railroads of Peru, consequent on the Bondholders' contract with the Government"33, argued the Vice-Consul, "will lead to the opening up of immense agricultural and mining fields, and will give life to all the great national industries of the interior, which so long have been awaiting the means of communication with the coast in order to spring into activity ...Peru may reasonably look forward to a prosperous future"34.

Historians do not have a common position on the importance of railroads for economic growth of Peru. Some have recognized that railroads did not impact the Peruvian economy as initially expected, but have not questioned the assertion that railroads were essential for economic growth. Their argument is that railroads had a low economic impact in Peru because only a few railroads were built; if more railroads had been built, the Peruvian economy would have grown faster. In 1919, for example, Pedro Dávalos y Lisón argued that most mining companies located in Pallasca, Huailas, Cajabamba, Hualgayoc, Cajatambo, Huallanca and some others experienced an "anemic life" because of the lack of means of communication, especially railroads35. More recently, Virgilio Roel also did not doubt of the potential positive effect of railroads. His criticisms to the actual railroad policies were rather directed against the allocation of railroads, which according to him reoriented the routes of commerce and led to large regional inequalities. The railway system, Roel argued, benefited the coast and deeply hurt the developing of the sierra, practically untouched by the steam machine36.

Other historians were more critical and questioned the assertion that railroads were necessary and sufficient for economic prosperity. In his classic Historia de la República, Jorge Basadre questioned the assertion that railroads were at least as beneficial as believed in the 1870s, and that Peru required much more than only investing fiscal resources on large rail investment projects. According to Basadre, "it was not enough with spilling the public fortunes to stimulate and develop work, give to the laborer the conscience of his own strength, multiply the value of properties and assimilate the public and private welfare, as it was believed back then"37. More recently, Carlos Contreras argued that although railroads may have helped solving transport problems in the central highlands, the mining sector faced other bottlenecks, such as the lack of disciplined working force and irregularities in provision of inputs. Railroad building was not a sufficient condition for economic growth38. Moreover, Rory Miller argued that the Central Railway only favored the industry of copper39. Overall the railway´s impact on the economy was much lower than in the copper sector40. For instance, little development in arable agriculture took place in the central highlands. "The [Central] railway, against expectations, provided no incentive to export to Lima low-value, high-bulk crops. In pastoral farming only a few haciendas were reorganized along capitalist lines. Most remained in an archaic state, farming extensively, and with production increasing only slowly"41. More recently, Zegarra (2011) shows that the impact of railroads on the growth of exports was largely related to the presence of scale economies. Railroads had a significant impact on the growth of exports of copper, sugar and cotton. However, the exportation of silver (which was transported in relatively smaller quantities than copper) was not influenced by the construction of the Central Railway.

III. The steam machine and time savings

One of the main benefits of railroads was the increase in the speed of transportation. The traditional system of mules and llamas was extremely slow. Compared to steam ships, however, railroads were not much faster. The savings in time costs then largely came from the substitution of steam railroad and navigation for the traditional slow system of mules and llamas. With the introduction of railroads and steam ships, Peruvians had now a much faster (and much more comfortable, certainly) system of transportation.

Table 2 reports time length of travel and the implicit speed of trains for a number of routes. Ordinary trains had a speed of at least seven miles per hour, whereas extraordinary trains were never slower than 12 miles per hour. In the North of Peru, for example, traveling in an ordinary train from Eten to Patapo took 3 hours and 45 minutes at an average speed of 7 miles per hours; but travelling in an extraordinary train only took one hour and a half at a speed of 17 miles per hour. Travelling from Pacasmayo to Guadalupe by railroad took 2 hours 45 minutes at an average speed of more than nine miles per hour. In the central region, an ordinary train took less than half an hour to complete the route Lima-Callao at an average speed of 18 miles per hour. Meanwhile, an ordinary train took 11 hours 45 minutes to complete the 138-mile route of Callao-La Oroya at an average speed of 11.7 miles per hour; whereas an extraordinary train took only 10 hours and 45 minutes and at an average speed of 12.8 miles per hour. Ordinary trains travelled in La Oroya-Cerro de Pasco at a speed of 12.8 miles per hour; whereas extraordinary trains travelled at more than 22 miles per hour. Similarly, in the South of Peru, travelling from Ica to Pisco took 3 hours and 40 minutes at a speed of 13 hours per mile on an ordinary train and took less than three hours at a speed of 20 miles per hour on an extraordinary train. Meanwhile, ordinary trains travelled at 15.8 miles per hour from Arequipa to Mollendo and at 18 miles per hour from Arequipa to Puno. Meanwhile, extraordinary trains had a speed of 25 miles per hour in curves and 31 miles per hour in straight line in the routes Arequipa-Mollendo and Arequipa-Puno.

Navigation in the Pacific Ocean was an important mode of transportation. Steam ships were much faster than sailing ships North to South. For instance, travelling from Paita to Callao (North to South), the speed was 250 miles per day for steam ships and only 38 miles per day for sailing ships. Similarly, from North to South, sailing ships required around 18 days to complete the route Callao-Iquique, whereas steam ships only needed 3 days and a half. Travelling South to North, the differences between steam ships and sailing ships were lower, but were still significant. For example, from Arica to Callao, sailing ships took six days, whereas steam ships only took two days and a half.

Railroads were as fast as steam ships and were faster than sailing ships. Ordinary trains were not slower than seven miles per hour, and could go as fast as 17 miles per hour. Steam ships usually traveled at a speed between eight and 13 miles per hour. Sailing ships traveled at a speed of less than five miles per hour, and could go as slow as two or less miles per hour.

Another important mode of transportation was the traditional system of mules and llamas. In fact, prior the construction of railroads most transportation was conducted by animals. Transportation of people and freight by mule or llama was slow. According to Briceño (1921), a good mule usually traveled at a speed of six miles per hour in the coast, five miles per hour in the highlands and less than four miles per hour in the jungle. The difference in speeds between the coast, the highlands and the jungle obeyed to the differences in the topography. The speed also depended on the weather. On raining season, for example, the daily journey had to be stopped by 2 pm or 3 pm. According to Briceño (1927), the daily journey was eight hours in the coast, five hours in the highlands, and five hours in the jungle. Then mules could complete up to 50 miles per day in the coast, 30 miles per day in the highlands and around 20 miles per day in the jungle42. Llamas represented a slower mode of transportation than mules. Contemporary sources indicate that llamas´ speed ranged between 12 and 16 miles per day43.

Railroads represented a much faster mode of transportation than animals. Evidence for specific routes shows the differences in speed between railroads and the traditional system of overland transportation with mules and llamas. In the central region, trains took less than a day to complete the route Lima-Cerro de Pasco, whereas mules or llamas could take several days. Proctor (1825), for example, indicated that the journey from Lima to Cerro de Pasco could usually take up to five days44. Carrying freight took longer since it was conducted with herds of full-loaded mules and llamas, which traveled in short stages, taking into account the comfort of the animals and the availability of alfalfa or herbs45. In the South, the railroad could complete the route Pisco-Ica in less than four hours; whereas travelers could take near a day through the dessert46. The journey was conducted by horse and through the dessert from 3 pm to forenoon the next day, avoiding the noon heat. The railroad of Mollendo-Arequipa-Puno was also much faster than traditional travelling. The speed of ordinary trains in this railroad was above 15 miles per hour. In contrast, in the 1850s S. S. Hills accomplished 104 miles from the port of Islay to the city of Arequipa in two days by horse and mule at an average speed of 48 miles per day47. Then Hills took nine days to complete the 415-mile route Arequipa-Cuzco by mule and through the mountains at an average speed of 46 miles per day, and took other nine days to accomplish the 260-mile route Cuzco-Puno at an average speed of 29 miles per day. It took less than 13 hours to complete the route Arequipa-Puno by an ordinary train, but it took six days by horse and mule. The route Arequipa-Cuzco, also in the mountains, took nine or ten days by mule, but less than a day by railroad.

Then railroads provided a much faster transportation than the traditional system of animal transportation. By the early 20th century, however, Peru did not have a large railway net. Most Peruvian towns were not touched by railroads, and therefore remained in the pre-rail era, depending on mules, llamas or walking as modes of transportation. As Dávalos y Lisón (1919) indicated, "... [since Peru had not] improved the scarce, narrow and dangerous roads ... the social and political life of the nation is more or less similar to that in the Colony. Towns are isolated some from the others. It is not easy for their inhabitants to travel and they never know the rest of the nation where they live... The people who are hired from the highlands to work for a salary in the haciendas of Pativilca, Casma, Chimbote, Chicama, etc, travel on foot such as during Inca times, needing from four to six days to walk distances of no more than 24 to 28 leagues, which would only require eight or ten hours if traveled by railroad or by car"48. Therefore, most towns had limitations to participate in trade with other towns, and so each town produced what it needed to live more some wool or mineral. In these circumstances, Peru could not take advantage of the vast sources of natural resources. For example, "... most mining companies located in Pallasca, Huailas, Cajabamba, Hualgayoc, Cajatambo, Huallanca and some others had experienced an anemic life because of the lack of means of communication. There is nothing richer in Peru in silver, lead, carbon and tungsten than Ancash, or nothing more abundant in gold than Pataz; but since we do not even have horseshoe roads in those provinces, every effort is exhausted for the impossibility of transportation. For the same cause, the great agricultural wealth of Jaen and Maynas has no value. Not even at ten soles per acre can land be sold, not existing roads to reach them..."49.

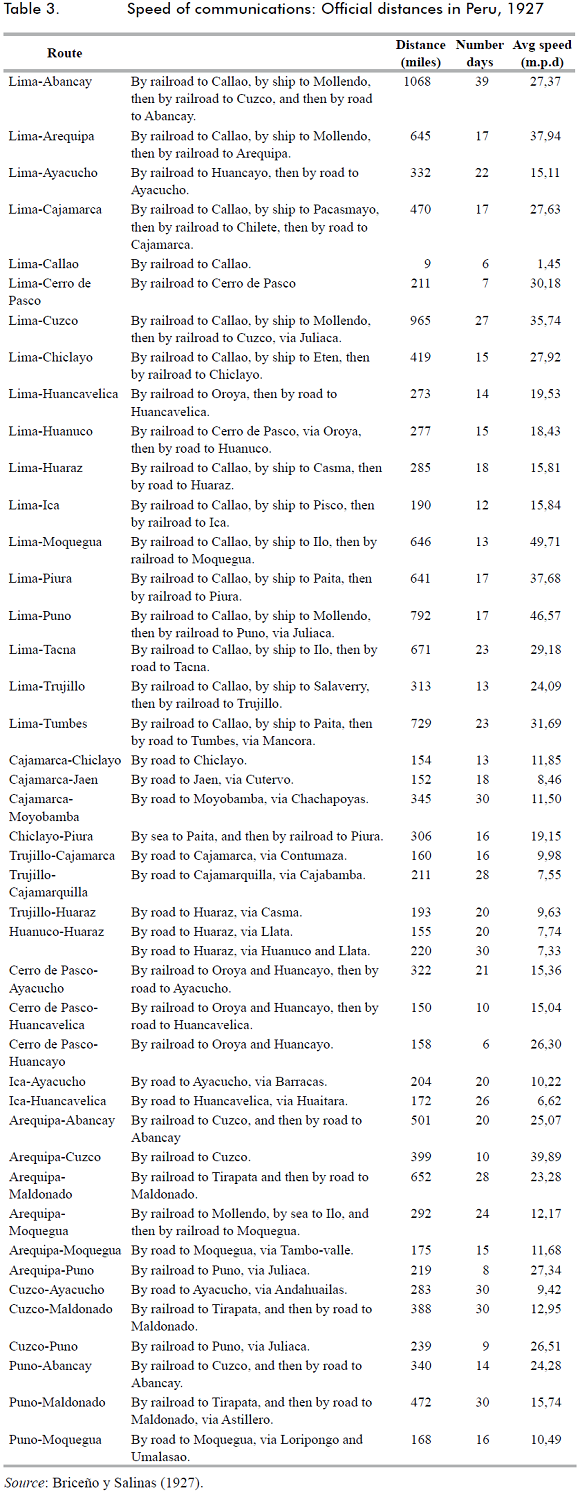

Official information shows the impact of railroads on the speed of communications. The "official distance" (also called judiciary, civil and military distance) measured the number of days required for mailing documents and packages for judiciary, civil and military procedures. Then the official distance was an official measure of the speed of communications. Table 3 reports the official distance and the speed of communications (miles per day) for a number of routes in Lima and other departments in 1927. First of all, it is important to mention that the speed was larger for longer routes, because some days were required for managing documents and packages in public offices: there was a fixed "time cost", independent on the distance50.

Lima had access to the sea and railroads as means of communication. As a result, in all cases, the speed was larger than 15 miles per day. Other cities also counted with railroads and navigation. Some of those cities were Trujillo, Chiclayo, Cerro de Pasco, Huancayo, Arequipa, Cuzco and Puno. Communication around these cities did not take much time. The route Cerro de Pasco-Huancayo, for example, was completed entirely by the Central Railway at an average speed of 26 miles per day; whereas the route Arequipa-Puno was completed in eight days at a speed of 27 miles per day. Similarly, the routes Cerro de Pasco-Ayacucho and Cerro de Pasco-Huancavelica were partially completed by the Central Railway; and the speed in both routes was more than 15 miles per day. In contrast, other cities were not near railroads or the sea, and therefore communications were much slower. Communication in the routes Trujillo-Chiclayo and Trujillo-Huaraz was only conducted by road; the speed in those routes was below 10 miles per day. In addition, it took 30 days to complete the 220-mile route Huaraz-Cerro de Pasco by mule at a speed of only 7 miles per day. In the South of Peru, the 204-mile route Ica-Ayacucho, conducted entirely by road, had a speed of 10 miles per day; and the route of Ica-Huancavelica, also conducted by road, had a speed of less than 10 miles per day.

Therefore, railroads provided a much faster mode of transportation than the traditional system of mules and llamas. Steam ships were also much faster than the traditional system of overland transportation. Since only one railroad ran parallel to the coast (Lima-Ancon-Chancay)51, railroads were not a substitute for navigation in the Pacific Ocean. Railroads and navigation were rather complementary. Then towns connected by railroad and waterways counted with a more rapid transportation and communication service.

IV. Pecuniary costs

In the previous section, we have shown that railroads (together with steam ships) were a much faster system of transporting people and freight than the traditional system of mules and llamas. But were railroads also cheaper? Did railroad companies charged lower passenger fares and freight rates than muleteers and llama-owners? It is possible that the higher speed of railroads relied on higher production costs, and therefore that passenger fares and freight rates were higher for railroads than for alternative modes of transportation. As this section shows, for most routes railroads provided a cheaper mode of transportation than mules. With respect to llamas, however, the story is different: llamas offered cheaper transportation than railroads for some routes, in particular for short distances.

Let us start presenting the data for railroad passenger fares and freight rates. Tables 4 and 5 report passenger fares and effective freight rates for a number of railroads. Effective freight rates are equal to railroad freight rates plus terminal fees. Terminal fees refer to costs of embarking and disembarking, which were fixed on the length of the trip52. Using information on distances, I calculated the passenger fares per mile and the effective freight fares per ton-mile. Passenger fares and effective freight rates are in dollars. Figures per mile are in U.S. cents. Railroads had two categories for passenger travelling. First-class fares were usually twice as much as second-class fares. On the other hand, railroads had several types of categories for freight. First class referred to imported goods. Third class referred to coal, petroleum and agricultural and livestock products53.

Railroads with frequent gradients and curves presented higher variable costs and therefore higher passenger fares and freight rates. For instance, first class passenger fares in 1908 were 5.8 cents per mile in Ticlio-Morococha and 4.6 cents per mile in La Oroya-Cerro de Pasco. In contrast, first class fares were less than 2.5 cents per mile in the coastal railroads of Lima-Callao and Lima-Chorrillos. As Basadre (1927) indicates, the route Ticlio-Mororocha was built in the top of the highlands and had significant slopes54. The railroad La Oroya-Cerro de Pasco, also expensive, was also built in the top of the Andes. La Oroya was located over 3,740 meters of altitude and Cerro de Pasco over 4,330 meters of altitude.

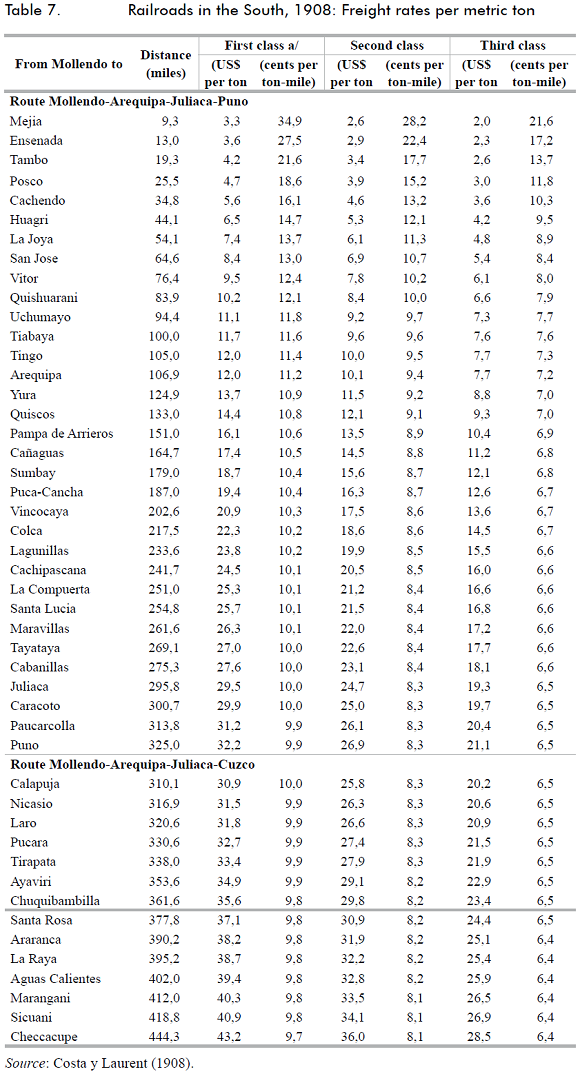

The presence of large fixed costs (terminal costs) made effective freight rates much higher for short distances than for long distances. Compare rates for different routes in the Central Railway Callao-Lima-La Oroya-Cerro de Pasco in 1908 (Table 6). First-class effective freight rates in cents per ton mile were 40.3 for Callao-Lima, 16.4 for Callao-Chosica, 15.2 for Callao-Matucana, 14 cents for Callao-La Oroya and 14.6 cents for Callao-Cerro de Pasco. Similarly, effective rates in the railroads of the South also declined as the distance increased (Table 7). First-class effective rates in cents per ton mile were 27.5 for Mollendo-Ensenada, 12.4 for Mollendo-Vitor, 11.2 for Mollendo-Arequipa, 10 for Mollendo-Juliaca, 9.9 for Mollendo-Puno and 9.8 for Mollendo-Sicuani.

A comparison of different railroads also indicates that short railroads had much higher freight rates per mile than long railroads. First class effective freight rates in 1908 were 53 cents per ton mile in the railroad Lima-Callao, 55 cents per ton mile in Lima-Chorrillos, and 46 cents per ton mile in Supe-Tambo Viejo. In contrast, first class rates were 9.4 cents per ton mile in Paita-Piura, 22 cents per ton mile in Eten-Chiclayo-Patapo and 14 cents per ton mile in Callao-La Oroya. Therefore the larger gains for the introduction of railroads occurred for long distances.

Traditionally, persons travelled on the backs of mules. Information on fares indicates that this system of transportation was not only slow, but also relatively expensive (Table 8). Railroads provided a cheaper transportation system than mules, especially for long routes. According to Briceño y Salinas (1921), renting a mule to transport a person in the coast or highlands cost 0.2 soles per kilometer, which was equivalent to 11 cents of dollar per mile. In contrast, railroad passenger fares were usually lower than 10 cents per mile in first class and lower than five cents in second class.

Similarly, effective freight rates were usually lower for railroads than for mules for long routes. According to Tizon y Bueno (1909), transporting bulk on mule cost around 21 cents per ton mile in the highlands. This rate was higher than third-class effective freight rates for most railroads, and was higher than second-class rates for railroads of more than 10 miles. Since mineral and agricultural products were transported in third-class wagons, transporting these products by railroad was cheaper than by mule. Other estimates indicate a higher freight rate for mules. According to Briceño y Salinas (1921), the cost of renting a mule for carrying freight was 0.10 soles per kilometer, which was equivalent to 42 cents of dollar per ton mile. This rate was higher than railroad third-class effective freight rates in all routes and was higher than railroad first-class rates in railroads of more than 10 miles.

In the central region, effective freight rates by the railroad Callao-La Oroya in 1908 ranged between 10 and 14 cents per ton mile, and effective freight rates from Callao to Cerro de Pasco ranged between 10 and 15 cents per ton mile. Muleteers charged higher rates. According to Pardo (1860) the cost of carrying bulk by mule was around 55 cents per ton mile in Lima-Callao in the central coast,55 and around 51 cents per ton mile in 1850s for the route Lima-Jauja,56 Deustua (2009) indicates that muleteer fares were around 26 cents per ton mile for the route Lima-Cerro de Pasco in 1836, and Miller (1976) indicates that muleteers charged rates of 43 cents per ton mile for the Cerro de Pasco-La Oroya in 190057.

In the South of Peru, railroads also charged lower freight rates than muleteers. Effective freight rates for the route Mollendo-Arequipa were 11.2 cents per ton mile for first class and 7.2 cents for third class; whereas effective freight rates for Mollendo-Puno were 9.9 cents per ton mile in first class and 6.5 cents per ton mile in third-class. Muleteer freight rates in the South were much higher. Flores (1993) indicated that muleteers usually charged 23 cents per ton-mile for the route Arequipa-Puno and 31 cents per ton-mile for the route Arequipa-Cuzco58. Similarly, according to the British Council of Islay, muleteers charged a rate of 31 cents per ton mile in 1856 and 42 cents per ton mile in 1862 for the route Islay-Arequipa59. In the route Ayacucho-Pisco, also in the South, the cost of carrying bulk on mule was 30 cents per ton mile in 1909, also higher than railroad freight rates.

The impact of railroads on transportation costs depended on the stage of economic growth. The evidence suggests that the supply of traditional transportation by animals was not perfectly elastic, so that increases in the demand for transportation had an impact on the price of transportation. In these circumstances, the construction of railroads had a larger effect on transportation costs as production levels increased60. According to Miller (1976), for example, as the production of copper started to boom in the late 1890s, and therefore the needs for transporting copper increased largely, the price of transportation increased substantially. The cost of renting a mule (in cents per ton mile) for the route Cerro de Pasco-La Oroya increased from 13 in 1896 to 58 in 1898 and then slightly declined to 43 in 1900. From 1896 to 1900 the cost of renting a mule increased more than twice. Similarly, the increase in coffee production in Junin increased the price of transportation. According to the Municipality of Chanchamayo, freight rates by mule between La Oroya and La Merced increased from 19 cents per ton mile in 1894 to 32 cents per ton mile in 1895 as a result of the scarcity of mules61.

For short distances, the advantage of railroads in freight rates was less evident. Transporting bulk from Callao to Lima in the Central Railway in third class cost 25 cents per ton mile. This rate was above Tizon´s estimate for mule rates, although it was less than Pardo´s estimate for 1860. In the South, transporting bulk from Mollendo to Ensenada (13 miles) cost 22 cents per ton mile. Similarly, in the North, transporting bulk from Paita to Colan (7 miles) cost around 25 cents per ton mile. At this rate, railroads were not necessarily cheaper for transportation than mules.

On the other hand, llamas constituted a cheaper mode of transportation than some railroads even for long distances. According to Tizón (1909), llama freight rates were around 11 cents per ton mile in the highlands. According to Aspíllaga (1889), a trip from Huarochiri to Cicla in 1889 had a freight rate of 12 cents per ton mile by llama62. In 1908 third-class freight rates in railroads were usually higher than llama rates. Only in the case of the railroads of Mollendo-Arequipa-Puno and Paita-Piura, railroads offered a cheaper transportation in third class than llamas; whereas Callao-La Oroya offered transportation at a similar rate. Freight rates in llamas were much lower than the rates in the railroad Ticlio-Morococha. Not surprising according to Miller (1976), around one third of mining production from Cerro de Pasco was carried to Callao by llamas in 1890, even though it was possible to carry it by railroad63.

The lower cost for using llamas is not surprising considering that llamas did not require much care, since they mostly fed upon practically all species of herbage from the mountains, and were better fit than mules for the natural conditions of the Andes64. In addition, the price of a strong grown llama ranged between three and four dollars and a regular llama could be purchased for two dollars65; whereas the price of a regular mule ranged between 45 and 50 dollars, and could reach up to 250 dollars66.

Steam ships also provided a cheaper mode of transportation than roads. For example, to travel from Callao to Arica in the South in first class cost 7.96 cents per mile in 1876 and 4.92 in 1928; whereas to travel from Callao to Puerto Pizarro in the North cost 2.66 cents per mile in 1876 and 6.17 cents in 1928. For most routes, first class passenger fares were below 10 cents per mile. Travelling on the deck was much cheaper. From Callao to Paita, for example, the cost of travelling on the deck was only 0.9 cents per mile. Overall, deck passenger fares were always below 4 cents per mile. In contrast, as indicated previously, the cost of travelling for a person on a mule was usually above 10 cents per mile. It seems then that steam ships provided a cheaper mode of transportation than mules.

Meanwhile, transporting freight was also cheaper by steam ship than by mule. Transporting bulk from Callao to Puerto Pizarro only cost 1.87 cents per ton mile, whereas transporting bulk from Callao to Arica cost 2.68 cents per ton mile. The cost was much higher in short routes: the cost of transportation between Callao and Tambo de Mora, for example, cost 10.41 cents per ton mile. Overall freight rates by steam ships were usually lower than 11 cents per ton mile. In contrast, mule rates were never below 20 cents per ton mile. This rate was always above ship rates67.

On the other hand, a comparison of passenger fares and freight rates for steam ships and railroads indicates that steam ships had lower freight rates than railroads; whereas there were no consistent differences in passenger fares. As it was explained above, however, most railroads did not run parallel to the coast. In fact, the only railroad that ran parallel to the coast was Lima-Ancon-Chancay. For most routes parallel to the coast, transportation could not be conducted by railroad, but by ship, or by mule. Then steam ships and railroads offered a complementary transportation service which tended to be cheaper than mules and sometimes even than llamas.

V. An international comparison of freight rates

A comparison of freight rates with other countries indicates that the construction of railroads had a similar effect on transportation costs in Peru than in other Latin American countries, and much larger effect than in the United States and Western Europe. The key difference between Latin America and the U.S. and Europe was the availability of waterways. Whereas the United States and Europe counted with a system of sea routes, canals and navigable rivers, in Peru, Mexico and Brazil the only waterway was the ocean. Therefore, most pre-rail transportation in Latin America was conducted using the costly system of wagons or the backs of animals. In contrast, the U.S. and Europe already had waterways, a relatively cheap system of transportation prior to the construction of railroads. With these differences, the impact of railroads on transportation was larger in Peru, Mexico and Brazil than in the United States and Europe.

Pre-rail transportation in the United States and Europe consisted of waterways and roads. However, waterways represented the main means of transportation for long distances due to its lower unit costs. According to Fogel (1964), by 1890 the average railroad rate was less than one cent per ton mile68. In contrast, wagon freight rates were around 13 cents per ton mile. Waterways were lower than railroad rates. For instance, the lake-and-canal rate on wheat from Chicago to New York was 0.186 cents, whereas the all-rail rate was 0.52 cents per ton mile69. Notice that the differences in cents per ton mile between railroads and waterways were very small in comparison to the differences between wagons and either railroads or waterways. Therefore, "... the crux of the transportation revolution of the nineteenth century was the substitution of low-cost water and railroad transportation for high-cost wagon transportation"70.

Similarly, in Europe, waterways were less costly than roads for long distances. In France, several rivers were used for transportation. River transportation became very important for transportation in the 18th and 19th century in spite of the difficulties that rivers imposed, which "reveals above all the inadequacy of the pre-rail transport infrastructure"71. In 1872 wagon rates were 0.48 francs per ton mile. Canals were much cheaper: canal rates were around 0.038 francs per ton mile. Meanwhile, railroad freight rates per ton mile were around 0.11 francs in 1872, 0.06 francs by the end of the 1880s and 0.04 francs by the end of the 1890s. In Scotland, waterways were also available and they were cheaper than roads. For the 19th century, in average freight rates of minerals per ton mile were 5.21 pence for carts, 3.86 pence for canals, 1.47 pence for east coastal routes and 0.66 pence for west coastal routes72. Railroad rates for coal were around a half and a third of road haul rates. As in the United States, in most of Western Europe the construction of railroads reduced overland transportation costs. However, since European countries had an extensive system of waterways which provide transported at a low cost, the overall impact of railroads on transportation costs was not very large.

In Latin America, waterways were not available for most regions. For Brazil, Summerhill (2005) indicates that most waterways in habitable regions were not navigable. "Waterways were not a viable alternative for most overland shipment. Navigable rivers were poorly situated. Coastal shipment complemented, but only rarely substituted for, movement overland"73. In these circumstances, to exploit and commercialize the interior meant that freight had to travel over Brazil´s coastal mountain range o the backs of mules, or at best on wagons or carts. This system of transportation was costly. Summerhill reports that in 1864 the average dry season rate by wagon was 62 cents of dollar per ton mile in San Paulo. The construction of railroads in Brazil reduced overland transportation costs: by 1913, the average railroad rate was only five cents of dollar per ton mile. In the case of Mexico, Coatsworth (1979) indicates that "except for local freight across three large lakes near highland population centers and short hauls up several rivers from the Gulf to the base of the mountains, internal water transport was unknown"74. Also, considering that most Mexicans lived far from the two coasts, coastal shipping did not play the same role as it did in the United States and in Europe. In Colombia, there were navigable rivers. However, for overland transportation mules were the main alternative to railroads. In this case, railroads also reduced transportation costs, although not the same extent as in Mexico and Brazil75.

Pre-rail transportation in Peru was costly to a large extent for the lack of a system of canals and navigable rivers, and because waterway transport was cheaper than overland transportation76. In these circumstances, the construction of railroads led to a significant reduction of transportation costs, replacing the use of mules in railroad routes77. Nevertheless, railroads not always provided a cheaper mode of transportation. Llamas were much cheaper than mules and were even cheaper than some railroads, especially the short railroads with high gradients in the central highlands.

VI. Conclusions

Prior to the construction of railroads, most Peruvians relied on traditional transportation by mules and llamas along the coastal dessert or the highland´s narrow, dangerous and exhausting roads. Waterways, usually cheaper than wagon and animal transportation, were not available for most towns. Rivers were not navigable in most of the coast and the highlands. Only the Pacific Ocean could be used for transportation through the coast. However, this mode of transportation was naturally constrained to coastal towns.

Peru experienced the construction of several railroads in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Several politicians and businessmen were very optimistic about the impact of railroads on the economy. It seems to be widely spread the belief that with the construction of railroads Peruvians would enjoy economic progress. The State and the private sector then invested large amounts of money to the construction of railroads in the coast and the highlands. By 1930 the railway length was near three thousand miles. However, although the construction of railroads may have meant a significant improvement in transportation, Peru still had a very low level of railway length in comparison to other countries in the region in the early 20th century. Most towns then still required mules and llamas for transportation.

Railroads did not compete with waterways but rather complemented them in transporting people and bulk. Railroads constituted a partial substitute to animal transportation in some routes in the North, Center and South of Peru. The Central Railway was a substitute of mules in the route Callao-Lima-Cerro de Pasco, whereas the railroads in the South were a substitute of muleteer in the route Arequipa-Puno-Cuzco.

The construction of railroads indeed represented an important innovation in Peru in the 19th century. First, railroads tended to be much faster than traditional overland transportation by mules and llamas. Mules (faster than llamas) took between nine and ten days to complete the route Lima-Cerro de Pasco, whereas trains took half a day by the Central Railway. Similarly, mules took nine days to complete the route Arequipa-Cuzco; whereas the Central Railway took less than a day. Railroads tended to be faster than steam ships, which were already much faster than animal transportation. However, railroads had a limited scope. Most of the Peruvian territory remained untouched by railroads. Then, as Dávalos y Lissón (1919) indicated, "the social life of the nation is more or less similar to that in the Colony. Towns are isolated some from others"78.

Moreover, In spite of the much greater speed of railroads, railroads did not necessarily charge higher passenger fares and freight rates. In the case of passenger fares, railroads were much cheaper than mules and llamas, with the exception of very short railroads in the Andes with many curves. In the case of freight rates, railroads were also cheaper than mules, especially for long distances. A comparison with other countries suggests that the impact of railroads in Peru on freight rates was larger than in the United States and Europe. In the absence of llamas, the impact of railroads would have probably been as large as in Brazil and Mexico.

However, llamas offered a relatively cheap transportation service in some routes, especially for the central highlands where rail rates were very high. That llamas were as costly as (or even cheaper than) railroads in some routes obeyed to the particular topography of the Andes, which influenced on production costs of railroads: the presence of several curves and changes in altitude made rail transportation very expensive. In the presence of this complex geography, however, llamas offered a cheap (although slow) mode of transportation.

FOOT NOTES

1 Some indicate that the impact of railroads on economic growth in the 19th century was large. Rostow (1962), for example, indicated that "the introduction of the railroad has been historically the most powerful single initiator of take-offs. It was decisive in the United States, Germany and Russia..." (Rostow, 1962, p. 302). Similarly, Fremdling (1977) indicates that railroads were vital for economic growth in Germany.

2 Fogel (1962), however, indicates that "a small aggregate social saving in the interregional transportation of agricultural products would not prove that the railroad was unimportant in American development." (p. 196). According to Fogel a multiplicity of innovations was responsible for industrialization in the United States, and no single innovation (not even railroads) was necessary for economic growth in the 19th century. Social savings of railroads were then low.

3 For a review of the European experience, see O´Brien (1983) and Hawke (1970).

4 Coatsworth (1979), p. 947.

5 Similarly, Ramírez (2001) indicates that the impact of railroads on the Colombian economy was not important, because railroads were built too late.

6 Some studies have analyzed the impact of railroads on the Peruvian economy. Miller (1976) studies the impact of railroads on the economy of the Peruvian central highlands. In one chapter, Contreras (2004) studies the interaction between railroads and muleteers in the central highlands of Peru. Finally, Deustua (2009) analyzes the impact of railroads on the mining sector in the central highlands. Recently, Zegarra (2011) shows that railroads were less costly than the traditional system of mules and llamas, which had an important impact on the growth of copper, sugar and cotton sectors.

7 Tschudi (1847), p. 138, 205, 206.

8 Wortley (1851), Vol. III, pp. 244-245. Similarly, Ernst Middenford observed in the 1890s that the geography of the Peruvian Andes was very complex. The long and steep ascents made the journey very exhausting. In fact, in the most populated regions, the terrain was rarely flat, with the exception of the valleys of Vilcanota and Jauja and the Titicaca plateau. (Middenford, 1974, Vol. III, p. 10).

9 Zegarra (2011).

10 Taken from Gootenberg (1993), p. 91. Malinowski was the Engineer in charge of building the Central Railway.

11 Manuel Pardo was an important businessman and politician, and President of Peru between 1868 and 1872.

12 Gootenberg (1993), p. 80. The support for railroads was not limited to the central region. In Arequipa, for example, several businessmen led by Patricio Gibbons and Joseph Pickering also supported the construction of railroads, because they would foster the "industrial life" of the region.

13 Total rail investment reached up to 220 million dollars from 1850 to 1900. Some railroads represented extraordinary engineering accomplishments, especially those that connected the coast and the highlands, passing through the Andes Mountains. The Central Railway, for example, which ran from Callao to La Oroya, was built through the Andes Mountains, reaching an altitude of 4,147 meters in Casapalca.

14 In the late 1870s and 1880s, however, railway track experienced a slow growth. By 1904, total railway track was 2,042 kilometers. In 1919, Pedro Dávalos y Lisón argued that most mining companies located in Pallasca, Huailas, Cajabamba, Hualgayoc, Cajatambo, Huallanca and some others experienced an "anemic life" because of the lack of means of communication, especially railroads.

15 They were the railroad Vitor-Sotillo in 1899, Ensenada-Pampa Blanca in 1906, Ensenada-Chucarapi in 1922. In the South of the department of Lima, several railroads were also built from the 1860s. A railroad was built in 1870, connecting the port of Cerro Azul with the town of Cañete. This railroad transported the products from the valley of Cañete, especially sugar and cotton. Some of the haciendas that demanded the services of this railway system in Cañete were Quebrada, Casa Blanca, Huaca, and Santa Barbara. Another railroad in the region was built in 1898, connecting the sea port of Tambo de Mora and Chincha Alta. To the South of Lima, the railroad Pisco-Ica was built in 1869, connecting the port of Pisco and the city of Ica.

16 This railroad had two branches: one branch from Calasñique to Guadalupe, passing through San José, Talambo, Chepén and Lurífico; and another branch from Calasñique to Yonán, passing through Montegrande.

17 In 1898 one landowner funded the construction of the railroad Huanchaco-Tres Palos, in order to facilitate transportation of products from the haciendas Chiquitoy, Chiclín and Roma to the port of Huanchaco. In 1896, another landowner funded the construction of a new railroad between the city of Trujillo and the sugar haciendas of Laredo and Menocucho in the valley of Santa Catalina. Another railroad was constructed in 1898 to serve the haciendas in the valley of Chicama, such as Roma, Cartavio, Chicamita, Chiclin and Chiquitoy.

18 This railroad ran parallel to the coast, passing through the nearby Hacienda of Puente Piedra. This railroad served several haciendas, such as Infantas, Chuquicanta, Pro, Naranjal, Carapongo, in addition to Puente Piedra.

19 They were the railroad of Hacienda Infantas (connected to the railroad Lima-Ancon), the railroad of Hacienda Monterrico Grande (connected to the Central Railroad), the railroad of Hacienda Pro (connected to the railroad Lima-Ancon), the railroad of Hacienda Puente Piedra (connected to the railroad Lima-Ancon) and the railroad of Hacienda Villa (connected to the railroad Lima-Chorrillos).

20 Milstead (1928), p. 68.

21 Taken from Gootenberg (1993), p. 91. Malinoskwi indicated that the greatest richness of Peru lie in the mountains and that it was important to send unemployed workers there. Taking into account the navigation problems in the rivers, it was important to build affirmed roads and railroads. As summarized by Bartkowiak (1998), p. 127.

22 Mc. Evoy (2004) includes the document "Estudios de Jauja".

23 Gootenberg (1993), p. 80.

24 The province of Jauja had rich lands capable of producing most foodstuff consumed by limeños. However, by the 1860s commerce between Jauja and Lima was practically nonexistent. The wheat used in Lima to make bread, for example, was imported from Chile.

25 Manuel Pardos´ main reason to support investment in railroads was the possibility of import substitution as lower transport costs allowed limeños to replace imports for Peruvian foodstuff. There would be no need of importing grains and other foodstuff from Chile if we could transport them from Jauja directly to Lima in only a few hours. A Northern railroad would join Cajamarca to the Pacific Ocean, passing through very rich lands and "bringing our mountains closer to the coast, of which there is more need than it is generally thought". Finally, a railroad in the South could be established in Chala or any other point in the coast to Cuzco with some branches, generating vitality to the Southern departments of Arequipa, Puno and Cuzco, and making the agricultural and metallurgical wealth of the region exploitable. Pardo adds that the railroad would cause a physical and moral revolution, because "the locomotive which changes by enchanting the aspect of a country for where it goes, also civilizes ..." (Mc. Evoy 2004, p. 86). Manuel Pardo was not the only leading businessman that defended the investment in railroads.

26 Meiggs (1876), p. 6.

27 Pike (1967), p. 125.

28 Meiggs (1876), p. 1.

29 Meiggs (1876), p. 55. Official communications and political speeches also highlighted the apparent large gains from building railroads. In a communication by Fiscal Ureta from his visit to the province of Tarapaca in 1869, Ureta indicated that railroads produced great benefits for the development of the economy, and that the industry of nitrate of Tarapaca would be largely benefited from the construction of railroads in this province; in these conditions, the nitrate industry of Peru would outcompete other countries. Meiggs (1876), p. 769, 770. The concession of the railroad Pisco-Ica of 1861 indicated that the construction of railroads should be promoted by all means, reducing distances, therefore facilitating mercantile transactions and contributing to national progress. In 1925, in the inauguration of the railroad Huancayo-Huancavelica, Congressman Celestino Machego indicated that the construction of this railroad represented the single most powerful innovation in the region. Machego even indicated that for centuries no other event would have greater economic implication for Huancavelica and that such railroad would end the vegetative and stationary life of this region. Speech of Congressman Celestino Manchego in the inauguration of the railroad Huancayo-Huancavelica (Pinto and Salinas, 2009, p. 189).

30 In the 1880s Charles Rand served as Secretary and Interpreter to the Mediators during the peace negotiations between Peru and Chile.

31 Rand (1873), p. 3.

32 Rand (1873), p. 3.

33 He refered to the Grace Contract.

34 Report of the Trade and Commerce of Callao (Vice-consul Wilson), Parliamentary Papers, 1890, LXXVI, 421, Cited in Miller (1976).

35 There is nothing richer in Peru in silver, lead, carbon and tungsten than Ancash, or nothing more abundant in gold than Pataz; but since we do not even have horseshoe roads in those provinces, every effort is exhausted for the impossibility of transportation. For the same cause, the great agricultural wealth of Jaen and Maynas has no value. Not even at ten soles per acre can land be sold, not existing roads to reach them...." (Dávalos y Lisón, 1919, p. 373).

36 The ciriticism of Roel to the railway system are in Roel (1986), p. 184, 185.

37 The mistake of the exclusivist myth of public works as a panacea, and material progress as main objective of the national policy, is evidenced in the decade of the seventies of the last century [1870s]: the magic of the money lent by Dreyfus and spent by Meiggs did not avoid, but accentuated later, the nightmare of the violence of July of 1872, the economic and fiscal crisis, notorious from 1873, the confinement of the State to its foreign creditors, the bankruptcy, the unfavorable conditions with which the country had to face international threatens which sifted upon it, and war ..." (Basadre, 1983, Vol. V, p. 136).

38 Contreras (2004), p. 172.

39 In particular to copper mining and smelting at Cerro de Pasco, Morococha and Casapalca.

40 Miller (1978), p. 46.

41 Miller (1978), p. 47. Some historians have also indicated that construction costs of railroads were large and that the construction of railroads the 1860s and 1870s was poorly planned and managed. Jorge Basadre indicated that "the lines of steal that Meiggs tended toward the clouds ruined Peru and were the announcement not of the regeneration and progress, but of bankruptcy and international catastrophe" (Basadre, 1983, Vol. V, p. 135). Similarly, Ugarte (1980) indicated that the construction of railroads was done without a plan and without previous studies. Meanwhile, Fredrick Pike indicated that "Peru poured all its energies and borrowed money and committed the sum total of its dwindling guano reserves to the building of railroads which ... could not possibly be profitably operated in the foreseeable future. Peru had begun a precipitous advance towards bankruptcy" (Pike, 1967, p. 126).

42 According to Cisneros (1906), a loaded mule could complete 34 miles per day in regular conditions in the highlands.

43 Tschudi (1847) indicates that the daily journey of llamas ranged between three and four leagues per day, i.e. around 12 miles per day. Similarly, Hills (1860) indicates that llamas rarely accomplished more than 12 or 13 miles per day. For Cisneros (1906), llamas could complete up to 16 miles per day. Since llamas never fed during the night, the llamero had to stop during the journey to allow the animals to graze.

44 Proctor (1825).

45 In 1847, the British Council John Mc Gregor indicated that animals usually took a rest in Obrajillo in the route Lima-Cerro de Pasco, before continuing the difficult journey up into the mountains (Bonilla, 1976, Vol. I, p. 130). The route Lima-Cerro de Pasco could then take 9 or 10 days for muleteers.

46 In his 1838-42 trip J. J. Tschudi completed the route Pisco to Ica in one day (Tschudi, 1847).

47 The description of the route can be found is Hills (1860).

48 Dávalos y Lisón (1919), p. 371.

49 Dávalos y Lisón (1919), p. 373.

50 The 9-mile route of Lima-Callao, for example, was completed in six days, even though the Central Railway only took 30 minutes to complete this route.

51 Moreover, part of this railroad was destroyed during the War of the Pacific (1879-1883).

52 In 1909 terminal costs were equal to 5 soles for first class, 4 soles for second class and 3 soles for third class (Tizon, 1909). Similar figures are reported by Basadre (1927). I then calculated the figures in dollars using the exchange rate of 1909.

53 In 1908, for example, in the case of the route Callao-La Oroya, first class freight rate was 14 cents per ton mile, second class rate was 12.1 cents per ton mile, and third-class rate was 10.3 cents per ton mile. In the route Mollendo-Arequipa, the first class rate was 11.2 cents per ton mile, and the third class rate was only 7.2 cents per ton mile. Agricultural products paid much less than imported goods.

54 Basadre (1927), p. 13.

55 The reference is Mc.Evoy (2004).

56 Manuel Pardo indicated that wool was transported by mule from Jauja to Lima in the Central Andes paying a price of 70 to 80 silver pesos per ton (around 83 dollars), at an implicit freight rate of 0.53 dollars per ton-mile.. The source is "Estudios sobre la Provincia de Jauja", included in Mc. Evoy (2004). The reference to the cost is in page 99.

57 According to Pinto and Salinas (2009), mule freight rates were 54 cents per ton mile for the route La Merced-Tarma in 1886, and 19 cents per ton mile for the route La Merced-La Oroya in 1894. Aspillaga (1889) reported that the cost of carrying bulk on mules was 50 cents per ton mile in Huarochiri-Chicla.

58 Flores (1993), Vol. I, p. 318.

59 The reports by the councils are included in Bonilla (1976), Vol. IV, pp. 99, 125.

60 Considering the reduction in freight rates due to railroads, it is not surprising that several private firms funded their own railroads to transport their own products. Some haciendas in the Northern coast that constructed their own railroads were Pucala, Tuman, Pomalca, Cayalti, Cartavio, Chicamita, Chiclin, Chiquitoy, Roma, Tambo Real, San Nicolas, Paramonga, and Humaya.

61 In 1895, the Municipality of Chanchamayo in the department of Junin sent a letter to the Congress, explaining that coffee was transported from La Merced to La Oroya by mule paying a freight rate of 1.40 silver soles per quintal in 1894 and 2.4 silver soles per quintal in 1895. The distance was around 79 miles, so the implicit freight rates per ton-mile were 0.19 dollars in 1894 and 0.32 dollars in 1895. According to this letter, the rapid increase in freight rates responded to the expansion of coffee production and the scarcity of mules. The letter is reported in Pinto and Salinas (2009), p. 130.

62 The rate was 0.5 dollars per ton-mile by mule. The data has been taken from Deustua (2009).

63 This reference has been taken from Deustua (2009).

64 Hills (1860), p. 101.

65 Tschudi (1847), p. 308.

66 Deustua (2009), p. 176-177.

67 Even llamas were usually more expensive for transporting freight than steam ships, especially for long routes. However, llamas were not used in the coast.

68 Fogel (1964), p. 23.

69 Fogel (1964), p. 39. However, water routes were much more circuitous than rail routes, so "the amount by which water costs exceeded railroad costs is far from obvious" (p. 24).

70 Fogel (1964), p. 50.

71 Price (1975), p. 13.

72 The figures come from Vamplew (1971), p. 45.

73 Summerhill (2005), p. 76.

74 Coatsworth (1979), p. 947.

75 According to Mc.Greevey (1989) muleteers charged around 80 cents per ton mile, whereas the railroad charged around 25 cents per ton mile. Notice that the mules charged between three and four times as much as railroads. This was a significant difference, but not as large as in Brazil. On the other hand, Ramírez (2001) shows that railroads did not have a significant impact on the development of the Colombian economy.

76 In fact, ocean transport rates in Peru were lower than mule and llama rates.

77 Not surprisingly, in a recent study Zegarra (2011) shows that railroads promoted the growth of copper, sugar and cotton exports.

78 Dávalos y Lissón (1919), p. 371-73.

References

1. ASPÍLLAGA, B. (1889). "Excursión a Huarochirí", AUNI, tesis No. 31. [ Links ]

2. BASADRE, F. (1927). Comparación entre ferrocarriles y caminos en el Perú, Conferencia dada en la Sociedad de Ingenieros. Lima, Sociedad de Ingenieros. [ Links ]

3. BASADRE, J. (1983). Historia de la república del Perú. Lima, Editorial Universitaria. [ Links ]

4. BONILLA, H. (1976). Gran Bretaña y el Perú. Los mecanismos de un control económico. Lima, Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, Fondo del Libro del Banco Industrial del Perú. [ Links ]

5. BRICEÑO y SALINAS, S. (1921). Itinerario general de la república. Lima. [ Links ]

6. BRICEÑO y SALINAS, S. (1927). Cuadro general para el término de distancia judicial, civil y militar dentro de la república y aun en el extranjero. Lima. [ Links ]

7. BULMER-THOMAS, V. (2003). The economic history of Latin America since independence. Cambridge (UK), Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

8. CISNEROS, C. (1906). Reseña económica del Perú. Lima, Imprenta la Industria. [ Links ]