Introduction

In this article, I study subnational-level recall elections in Peru. Recall elections are sometimes considered a mechanism of direct democracy. For example, Altman (2011, p. 11) classified recall elections in his typology of the mechanism of direct democracy as a subtype of popular initiative. However, in Altman’s (2019, p. 6) later work, he excluded recall from the mechanisms of direct democracy, considering that citizens do not vote on specific issues but, rather, that recall targets the elected authorities. Kaufmann, Büchi and Braun (2008, p. 91) hold a similar position to Altman in considering that recall is not a mechanism of direct democracy. For the purpose of this study, I too position recall elections as a special category of elections outside the realm of direct democracy. The body of literature on recall elections is not particularly large as these are a scarcely used tool in democracies. Despite this, there have been some recent publications on the topic (Geissel & Jung, 2018; Holland & Incio, 2019; Welp & Milanese, 2018; Welp & Whitehead, 2020; Whitehead, 2018).

Recall elections give citizens more control over public administration. It is they who initiate the process, which, in turn, is meant to serve as an insurance mechanism against inert politicians and institutions (Altman, 2011, p. 2), rendering such elections a tool of accountability. The greatest obstacle to examining the impact of recall is the lack of data, as this tool is used in a few countries and there is often little possibility to conduct a proper analysis. Peru, however, given its twenty years of practice with local-level recalls, is an ideal example for this research.

The central research question is: What variables can explain the use of recall in Peruvian municipalities? The research problem is summarized as: Why is recall used more in some municipalities and why is it used at all in light of the fact that it brings high-level instability to the political system? A successful recall results in shortening the term of office for a mayor or council member, and there are two possible explanations why such action may be taken: the first, in the case of Peru, is that recall has generally been used by the opposition as a mechanism to gain power (Holland & Incio, 2019; Tuesta Soldevilla, 2014; Welp, 2016). I have extended research on recall elections and tested new variables that are linked to political parties and invalid votes, and created a new variable that measures a mayor’s political performance. Hence, the question of whether recall is used as a mechanism of accountability. In order to examine these questions, I use a large dataset of different variables from Peruvian municipalities and municipal elections to test and extend the current theoretical assumption.

I find that recall elections were held most frequently in municipalities with high local electorate party membership when the percentage of blank votes was low, and the margin of victory was low in previous municipal elections. The key variables for the successful removal of a mayor are the political experience of the organizer of a recall procedure, the number of null votes, and votes for the winner in previous municipal elections. Except for the margin of victory, these findings are a new contribution to the literature related to political science. Even though these mentioned variables are not part of one coherent theory, my main argument is that there is one thread that connects them all. All these variables can potentially predict the success of mobilization, which, in turn, serves as the thread that links all the variables in this research. I explain the relationship between mobilization and each of these variables in greater detail in the theoretical section of this work.

I examine the role of recall elections in Peruvian municipalities and I use logistic regression to analyze a dataset with recall elections until 2013. I test the theoretical assumptions of elite mobilization theory and other theories related to the functions of political parties and invalid votes. Recall elections were held most frequently in municipalities with high local electorate party membership, when the percentage of blank votes was low and the margin of victory was low in previous municipal elections. The performance of mayors and socio-economic variables such as the Human Development Index, education, and income, on the other hand, do not affect the likelihood of recall elections or the removal of mayors. The key variables for the successful removal of a mayor are the political experience of the organizer of a recall procedure, the number of null votes, and votes for the winner in previous municipal elections.

In the first section of this work, I present a review of the literature, the theoretical framework, and the hypothesis of the paper. In the following section, I explain the research design and methodology and, in the final section, I interpret the results.

Theories and hypotheses

1) Party competition and membership

When election results are close, competitive elections increase voter turnout (Blais, 2000; Blais & Dobrzynska, 1998; Caldeira & Patterson, 1982; Franklin & Hirczy, 1998). Competitiveness mobilizes voters because citizens feel that their vote is important, leading them to attend elections more frequently. This argument is based on the theory of rational choice (Downs, 1957), which assumes that rational voters choose to vote depending on the extent to which their vote is key to the outcome of the election. In other words, they believe that, in close elections, their vote may have a more decisive role than it would if one party dominates the election.

Voters feel election closeness, as do political elites. In the case of close elections, there is mobilization on the part of the political elites themselves, in an attempt to win the close elections. (Aldrich, 1993, 1995; Cox & Munger, 1989; Kirchgässner & Schulz, 2005; Rosenstone & Hansen, 1993). Elites invest far more funds in campaigns and overall mobilization because they have a greater chance of winning. As such, it should be possible to predict the holding of recall elections by applying elite mobilization theory. It is clear from previous research that politicians that lose the elections, often attempt to recall a mayor and councilors of their seats. To do so they need to initiate2 new municipal elections to replace the winning party (Tuesta Soldevilla, 2014, p. 21; Welp, 2016, p. 12). If the winner of the elections clearly dominates, the defeated local political leaders should not have the incentive to mobilize citizens to collect signatures for a recall to try to remove a mayor. If a mayor is successfully removed, it is also less likely that he or she will win in the new municipal elections. In a recently published article, Holland and Incio (2019) confirm that recall is more often held in municipalities where a party wins by a small margin. However, some key variables were not verified; i.e., party membership that is closely linked to elite mobilization theory.

Political parties have several functions. One of these is that they mobilize voters and their members. Often, party members themselves are responsible for mobilizing voters (Scarrow, 1996; Scarrow & Webb, 2017), and this can occur in various ways, whether through election campaigns, convincing, donating money or any other voluntary activity. Mobilizing within local election campaigns has a key impact on voter turnout and election outcomes (Carty & Eagles, 1999; Clarke, Sanders, Stewart, & Whiteley, 2004; Denver & Hands, 1997; Gerber & Green, 2000; Hillygus, 2005; Johnston & Pattie, 1997; Karp, Banducci, & Bowler, 2008).

Peru’s levels of party institutionalization are very low. Indeed, Levitsky (2018) considers that after the return of democracy in 2001, the political parties in Peru have tended to be very weak. This is also true in terms of the country’s party membership, which, as revealed by Došek (2016, p. 179) has the lowest rates of all the countries in Latin America for which data are available. The degree of membership in political parties naturally varies across Peru, and distinctions across municipalities around the country may raise new questions.

This study compares these municipalities, showing significant differences among them in terms of party membership and its impact on the mobilization of the electorate. Even though party system institutionalization is low in Peru (Levitsky 2018) and parties and movements tend to disappear very often, this does not necessarily mean that party membership cannot offer information and prediction of electorate behavior. Quite the opposite is true, given that the mere fact that a higher share of the electorate is even interested in politics in the form of membership in parties, predicts that there is greater citizen engagement and possible mobilization. This is true regardless of whether a party disappears, whether leading voters to have to change their party, or whether they have to become non-partisan.

In his research of 36 countries, Whiteley (2009, pp. 142–148) reveals that there are considerable differences between active members of the party, party members, former party members and citizens who have never participated in any political party. Citizens with experience in political parties engage in political affairs more than those with no experience in this respect. In his multi-level participation model, he shows that the percentage of party members at the aggregate level is a strong indicator of the participation of individual citizens. Thus, party members and citizens in municipalities should be more engaged in politics. Another of the forms of participation that is examined is the signing of petitions, which, in Peru, is a crucial argument for why it is more likely that a sufficient number of signatures could be gathered for the initiation of a recall in Peruvian municipalities where local electorate party membership is higher.

I argue that there could be important variables other than the closeness of the previous municipal election for predicting recall. In this respect, I examine the influence of local electorate party membership. Local political leaders can use their members as a resource by which they can mobilize the local electorate. This can still happen in the rather low level of party system institutionalization where political parties disappear as they do in Peru. Whiteley’s (2009) research shows that being a party activist, party member, or ex-member increases participation and civic engagement in politics. Thus, one may expect for local political leaders to find it easier to mobilize electorate that has a higher share of party members as one may assume greater engagement in politics in the form of signing petitions to hold recall elections. While elite mobilization theory would explain successful mobilization leading to successful initiation of the recall given that the signatures of 25 percent of the electorate are required to initiate such a process, it would not necessarily explain the successful removal of a mayor in a recall election in which a mayor’s supporters vote alongside the whole local electorate. Therefore, there must be greater support than 25 percent of the electorate for a mayor to be removed. The following hypothesis examines the initiation of recall elections.

H1: The greater the party membership in a municipality, the more likely it is for recall elections to be held.

2) Invalid votes

The next hypothesis concerns a phenomenon that is typical of a number of Latin American countries; i.e., a large number of invalid votes in elections. In the case of the Peruvian municipal elections, invalid votes include blank votes (blancos) and null votes (nulos). A number of studies link citizens’ invalid votes to their dissatisfaction and therefore as a protest against political elites (Power & Garand, 2007; Power & Roberts, 1995; Uggla, 2008). Kouba and Lysek (2019) recently published a comprehensive meta-analysis of invalid voting. They divide two categories of invalid voting in which voters cast invalid votes unintentionally or intentionally. They divide intentional invalid voting on the basis of dissatisfaction into three categories: unsupportive, disempowered, and disenchanted. All three classifications are based on the level of political support and a sense of subjective political empowerment. Disenchanted voters feel that it makes no difference which party wins an election. Hence, this type of invalid vote often occurs in political systems with weak competition.

Studies that differentiate blank and null votes are scarce. Most analyze blank and null votes together and treat them as one (Power & Garand, 2007; Power & Roberts, 1995). However, I argue that they are not the same and that there is an important difference between the two. For some, blank votes are a clearer sign of protest because voters voluntarily and deliberately do not mark any of the candidates and put a blank ticket in the ballot box. While in the case of a null vote, the voter can make an involuntary error that invalidates his vote (Cohen, 2018, p. 403). Driscoll and Nelson (2014) examined the difference between blank and null votes based on the Bolivian judicial elections. They investigated Bolivian voters for both types of invalid votes for political reasons; however, a null vote was more typical for sophisticated voters who were dissatisfied and thus expressed their protest. In contrast, less-informed voters gave blank votes for reasons of greater confusion and apathy. Barnes and Rangel (2018) studied mayoral elections in Chile where they distinguished between null and blank votes before and after the abolition of compulsory voting. They found that with and without compulsory voting, both blank and null votes reduced as electoral competitiveness increased. Peru has a much higher number of invalid votes, ranking first in Latin America (Kouba & Lysek, 2016).

Because the number of invalid votes may relate to the municipality’s competitiveness, I examine whether municipalities with a lower number of invalid votes are more likely to hold a recall. In these cases, citizens should not be as disenchanted and would not want to waste their votes by making them invalid; in turn, political leaders should be able to mobilize for a sufficient number of signatures to hold recall elections, as research suggests that invalid votes show voter apathy and one may assume that this would make the collection of signatures less likely. It is important to acknowledge Peru’s compulsory voting system, which results in it being more costly for a voter to protest by abstention in elections than casting an invalid vote. At the same time, after controlling all the variables, especially the High Development Index (highly correlated3 with levels of education), a significant strength of prediction may apply for the number of blank votes, but not for null votes. In the case of null votes, voters can spoil their ballot unintentionally, which is why the hypothesis includes only the blank votes that voters cast deliberately. As in the case of the first hypothesis, this hypothesis too is only concerned with the initiation of the recall; as the mobilization and initiation of a recall differ from the vote concerning the fate of a specific mayor.

H2: The more blank votes, the less likely it is for recall elections to be held, but this does not apply in the case of null votes.

3) Performance of the mayor

One of the basic arguments to support recall is that it gives people the possibility to remove bad politicians. The reasons for the recall of politicians in the USA are often linked to corruption and the misuse of resources (Bowler, 2004, p. 209). Recall is considered an insurance mechanism, meaning that politicians are constantly controlled by the public and any incompetent or corrupt behavior can lead to a petition for recall (Zimmerman, 2014, p. 112). The organizers4 of the 2012 recall elections in Peru, gave similar reasons as the above. For example, the violation of election promises, misappropriation, incapacity, nepotism, abuse of power or non-transparent municipal management (Oficina Nacional de Procesos Electorales 2013a: 81).

Classical economic theory assumes that the voter rewards the incumbent in good economic times and punishes him in bad times (Lewis-Beck & Stegmaier, 2008). Sakurai and Menezes-Filho (2008) illustrated that spending money is directly related to the future success of the mayor in Brazilian municipalities. This is based on the accountability of politicians. Mayors try to perform well because they worry about recalls as mayors that are not effective are recalled by citizens. However, Holland and Incio (2019) revealed that in Peruvian municipalities, better mayoral performance does not increase the likelihood of initiating successful recall elections, but actually decreases the likelihood of recalling a mayor in an already initiated recall election. I also examine mayoral performance in a different way as I explain in the next section. My hypothesis is as follows:

H3: Mayoral performance does not affect the likelihood of holding recall elections, but it does affect the success in the removal of a mayor in an already initiated recall election.

4) Organizers of recall elections

In order to confirm the elite mobilization theory in Peru, it is necessary to investigate recall organizers in particular. Quintanilla (2013) claims that prior research shows that politicians who lost in previous elections organize recall elections only in minority cases and the conclusions of previous authors may be based more on subjective feelings. Holland and Incio (2019, p. 15) support this and claim that in 18 percent of cases organizers were candidates in the previous municipal elections between 2002 and 2014. However, Tuesta Soldevilla (2014, p. 22) argues that if the organizers were not counted only as candidates from the previous elections and their political party membership was also included, this number would increase greatly. I expand on this issue below.

Past research does not clearly indicate that recall organizers are necessarily associated with a party. I examine and quantify whether organizers ran for any election in the past and whether they were members of the party. However, in my next hypothesis, I examine the relationship between the removal of a mayor in already initiated recall elections and the electoral experience of the organizer. I assume that people with political (electoral) experience are more likely to be successful at mobilizing the electorate than in actually removing a mayor. This assumption is based on the literature about candidate quality (Green & Krasno, 1988, 1990; Jacobson, 1990; Lazarus, 2008), which points to quality candidates being more successful in elections. The quality of candidates is usually measured by electoral experience; i.e., candidates running for office and winning elections. Thus, I expect recall organizers with electoral experience to be better quality organizers in this respect and more successful at mobilizing people to remove a mayor as they have electoral experience and they manage to get enough signatures to initiate recall elections.

H4: In successfully initiated recall elections, the organizers with political experience are more successful in recalling a mayor.

Data and research design

I examine the period of recall elections from 2001 to 2013 in Peruvian municipalities that coincide with municipal elections from 1998 to 2010. However, as I will explain later, I was able to use regression models only for some periods given the lack of the necessary data and I use correlations for different periods as I do not have complete data to draw up comprehensive models. Unfortunately, I was also unable to analyze the first recall elections under the new rules in 2017, as they were held only in 27 municipalities (1.6 ). This is too small a number with which to be able to use the statistical methods I employ, and given this small number, they can be considered rare events in terms of statistics. In the previous period, recall elections were held in 24% of the municipalities, and this sharp contrast makes it impossible to include both periods in the same model. For a sample of this size, qualitative methods may be more appropriate. Moreover, due to the changes in the regulations, for the opposition to initiate a recall seems to make less sense5. I therefore focus on a period when the institutional rules were the same.

Dependent variables

I use two basic analyses and two dependent variables. The first analysis deals with the likelihood of holding recall elections and I examine the difference between the municipalities where recall elections were held after the municipal elections. If recall elections were held, I code this as 1; if not, I code it as 0. The second analysis examines the likelihood of the mayor’s removal if recall elections are already initiated. Again, the successful removal of a mayor is coded as 1, and failure as 0. These processes differ greatly from each other and therefore need to be examined separately as was mentioned in the theory section.

In the case of recall elections, citizens vote for each politician separately. However, I only examine a mayor in the second analysis because it is the most important office in the municipality. Recall elections held in 1146 municipalities until the year 2013 involved 1113 mayors (Infogob-JNE, 2017). During recalls, voters can make decisions regarding multiple politicians in the same recall; however, I do not examine the 4083 councilors. Current research shows that councilors face recalls mainly because the opposition attempts to initiate new municipal elections6 (Tuesta Soldevilla, 2014, pp. 25–27). Thus, it is not really their performance that is involved and the model would be much more complicated to interpret because it would also be necessary to distinguish possible councilors who do not come from the mayor’s party.

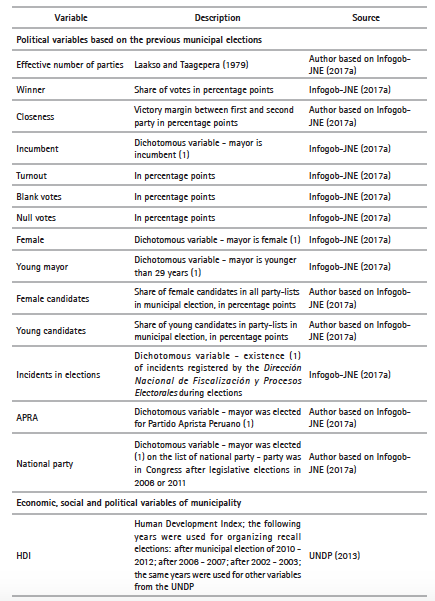

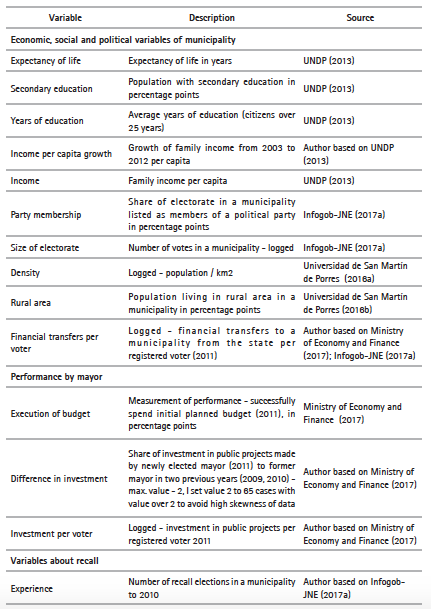

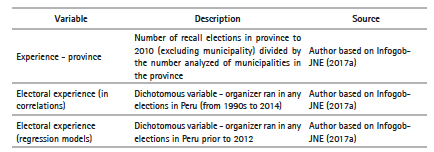

Independent variables

My first independent variable is the percentage of party members in the local electorate. Information about this variable is not available for earlier than 2010. The other two independent variables are the percentage of blank and null votes. As I discuss in the theory section, blank and null votes are different and I therefore examine them separately. The third independent variable is the mayor’s performance. As the first variable for measuring performance, I use the investments made by the mayor in the first year of being in office. If no investment is made, the inhabitants of the municipality would see this because roads, schools, or other public buildings and areas would not be repaired or built. I measure this variable as the share of investments in the first year of a mayor’s term in office over the previous two years. This variable, which compares a period within a municipality is ideal, as candidates for mayor generally promise investment and if they then invest less than the previous mayor (in the case of reelected incumbents, then the same mayors in the previous period), citizen dissatisfaction can be expected. The advantage of using this variable is that it compares periods within each municipality, thus limiting the need to control for financial transfers from the central government (inputs) as it is reasonable to expect that municipalities receive more or less the same financial resources every year. The potential changes in the distribution of financial resources from the central government would reflect all municipalities. Thus, during the first year of their term in office, mayors should have to perform to similar standards. Local government performance and efficiency literature very often includes an investment in infrastructure or other public services as an output variable to measure performance (Narbón‐Perpiñá & De Witte, 2018). This is the direction I follow in this study.

In the Peruvian context, one of the mayor’s main tasks is to plan and implement the budget. Therefore, the second variable measuring performance relates to the budget and it is a measure of how much the original budget has been spent successfully in the first year in office. In Peru, for the sake of transparency, individual budget items are documented and, to combat corruption, mayors face obstacles in actually spending these resources (Sexton, 2017, pp. 11–23). In Peru, this variable is often used7 as an indicator of performance and also included as such in research (Holland & Incio, 2019; Leon & KleineRueschkamp, 2018; Pique, 2019; Sexton, 2017). If the mayor and his team are not proficient in the administration, it is quite likely that the planned budget will not be exhausted and that the planned projects will not be executed. I use the first year in office (2011) to measure the performance because it is a sufficient time period for citizens to evaluate the mayor’s performance, and it is when a recall procedure could be initiated. In the following year (2012), a recall election could be held in a municipality. I use the first year in office (2011) also as a measurement for the recall elections held in 2013 as I examine whether recall elections were held in the municipality during one mayor’s term in office (2011-2014). It is also logical that in the 2013 recall elections, the mayors were judged for the first year and the mobilization process for the recall could have already begun in 2012, but no formal obligations were complied by for the 2012 recall; the recall was therefore delayed in the given municipality. The budget figures available for all municipalities only date as far back as 2008. The first year in the mayor’s office after the municipal elections in 2006 was in 2007, making it impossible to examine the period between 2006 and 2010 based on performance data. Holland and Incio (2019) also used the execution of a budget in their study as a variable and they deal with this lack of data using by the proxy from 2008.

The last independent variable involves the recall organizer. I code a person with electoral experience as 1, if they ran in an election. This includes elections prior to 20128 at local, regional, and national levels. Information about recall organizers is provided by the National Jury of Elections (Jurado Nacional de Elecciones, JNE).

Control variables

I use several control variables that draw from substantial research that can generally influence electoral behavior, and are thus also validalso for elections in Peru (Geys, 2006; Holland & Incio, 2019; Kouba & Lysek, 2019). The first control variable concerns socioeconomic factors. Traditionally, citizens with lower levels of education, lower income, and lower social status are considered to be underrepresented among politically active citizens (Verba & Nie, 1972). Higher education itself is considered to be an important variable in terms of understanding protest (Barnes et al., 1979). I use the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Human Development Index (HDI) as a proper measure of a municipality’s social and economic development. Also, based on the analysis of the data from the Latin American Public Opinion Project (LAPOP), it is clear that in municipalities where GDP is rising, more citizens trust the municipal government (Montalvo, 2010).

Other control variables include election closeness and the effective number of parties (ENP). Closeness is measured as the percentage difference between the second and the first candidates in the election. The percentage difference is a good measure to be used in the Peruvian context, as the winner always receives more than half the seats in the municipality and the electoral system is heavily disproportionate. I include the ENP mainly because of party coordination. Successful electoral strategic coordination decreases the number of political parties competing in elections (Cox, 1997, p. 4). ENP can measure this and it should be easier to organize and mobilize to initiate recall elections when there are fewer political parties. I use the winner’s percentage of the vote for models that deal only with successfully initiated recall elections. In this case, there was already enough coordination for a successful recall and, because all citizens can vote, the winner’s last percentage in the election is more important. A mayor must receive more than 50 percent of valid votes to be recalled and 25 percent of the signatures of the electorate are enough to initiate a recall.

I use turnout as an additional variable to control the possible effects of political participation. Spivak (2004) finds that turnout is an important factor for the likelihood of recall elections in some states in the United States, as the required percentage of signatures to initiate recall elections in some states depends on the turnout in previous elections. Therefore, when abstention in the previous elections is high then it is easier for organizers to collect the required number of signatures as the number is low. However, voting in Peru is compulsory, and the required number of signatures is fixed at 25% of the electorate. Thus, turnout should be a less important variable for the likelihood of recall in Peru than in some states in the United States. I include the size of the municipality, density, and urbanization to control for the potentially easier organization of the recall in smaller areas and in high-density ones.

Next, I control for the relationship between politics at national and local levels. The most important political party in Peru of the 20th and 21st centuries is APRA (Partido Aprista Peruano); President Alan García’s party and where his term ended in 2011. The second-order election theory, explored especially in the European Parliament elections, posits that voters often try to punish the ruling parties in non-national elections (Oppenhuis, Van der Eijk, & Franklin, 1996). The greatest number of mayors came from APRA. I control this potential effect on the likelihood of a recall, and I use control variables for gender and age. In this respect, men are still perceived by a part of the population as better political leaders than women. However, according to the World Values Survey, in Peru, 30.3 percent of people strongly disagreed with this claim in 2012; 44.8 percent disagreed, and 18.9 percent either strongly agreed or agreed (Inglehart et al, 2014).

Age is very often used as a variable to explain the likelihood of protest. Young people participate in protests more than the elderly (Barnes et al., 1979; Dalton, 1996). JNE offers information about the age and gender of candidates, and considers political candidates under the age of 30 as young (joven). I measure the percentage of young people that run for office on all lists in a municipality as well as their gender. Subsequently, I consider whether the mayor is a female, which I code as 1, or male, which I code as 0, and whether he or she is under the age of 30, coded as 1, or over it, coded as 0. I also control for whether the mayor won the previous municipal election (incumbent).

I use financial transfers per voter9 from the state to municipalities as another control variable. The Peruvian Ministry of Finance reallocates funding to individual municipalities based on multiple criteria. This is revenue to which every municipality is entitled; however, in areas where resources are mined, they also receive mining revenue (canon). Thus, municipalities do not receive the same amount of funds in proportion to their populations.

I control for the previous use (before 2010) of recall elections in a municipality by counting all past recall elections. According to the psychological concept of adaptive learning, voters can adopt a habit (Bendor, Diermeier, & Ting, 2003; Kanazawa, 2000; Sieg & Schulz, 1995), so that citizens who voted in the past are more likely to do so in the future. Thus, a municipality’s past experience can influence the likelihood of new recall elections. I examine this also in the provinces by first adding up the total number of recall elections in the province, then deducting the number of recalls in the municipality from this sum in the province, and finally dividing it by the number of municipalities analyzed in the province. Citizens from neighboring municipalities in the province can learn about the recall and use this tool themselves.

The final control variable involves irregularities in elections. I measure this variable as the presence of incidents registered by the National Directorate of Inspection and Electoral Processes (Dirección Nacional de Fiscalización y Procesos Electorales, DNFPE) during municipal elections. I code the presence of incidents as 1 and their absence as 0. In this case, the DNFPE identified no incidents serious enough to invalidate whole elections, but only incidents which were considered a problem during the electoral process.

Models

I use logistic regression, which is the ideal tool in this case as holding recall elections and the mayor’s removal are dichotomous dependent variables.

I create several regression models to verify the hypotheses and search for associations between variables in the correlations (in the Appendix, Table 5). Because of the higher number of variables, I place emphasis on avoiding multicollinearity. Accordingly, I treat variables based on theoretical considerations very cautiously in individual regression models, and conduct a number of tests to avoid possible multicollinearity10.

Four logistic regression models include as many variables as possible and examine the period after the municipal elections in 2010. I include all variables in correlations that were at my disposal from municipal elections since 1998 in the Appendix as a way of controlling logistic regressions that examine the recall only after 2010. In the rare11 case that municipal elections were annulled, I do not examine that municipality in the study period. I explain all variables and provide information on their source in Table 4 of the Appendix.

Results

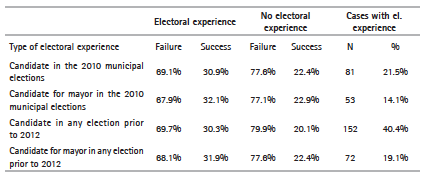

I first analyze all 1113 recall elections in which the mayor faced a recall from 1997 to 2013 and the organizers of these recalls. I found that 56% of the organizers ran for some election in the past and 50.3 percent of them were party members. The politicians running in elections and party members are not exclusive categories as a politician does not have to be a member of a party to run in elections and a party member does not necessarily run in elections. However, organizers who already ran for elections or were members of the parties constituted 74.4 . Only a quarter of the organizers had no links to political parties and never ran in elections. I confirm the assumption that Peru’s recall elections are a highly politicized instrument. It seems that recall is used by political actors who take advantage of this tool to regain power themselves or to help their party do so.

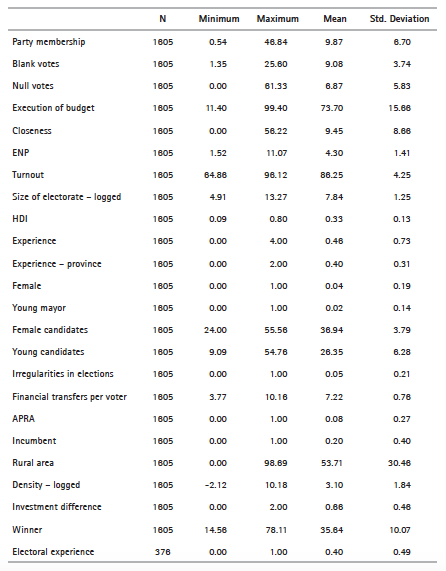

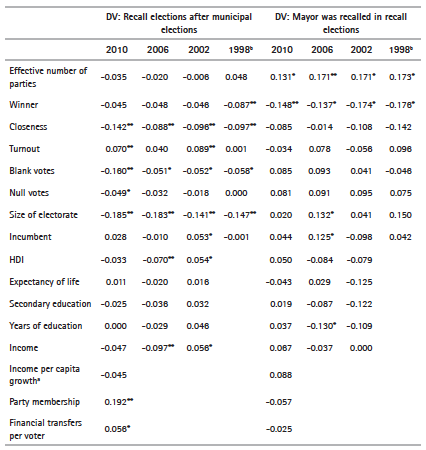

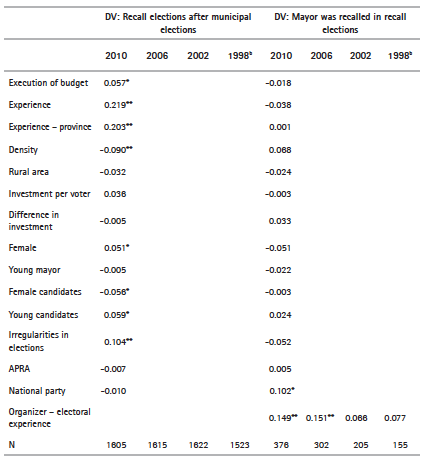

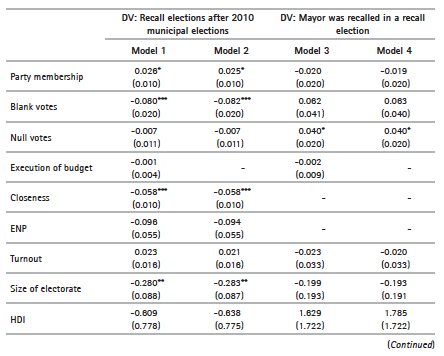

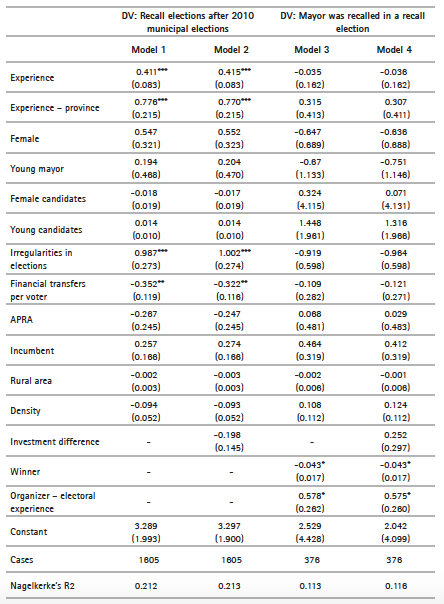

Table 1 offers descriptive statistics of variables that I use in the logistic regressions. The models (Table 2) unambiguously show that the political-electoral variables are very important in terms of the likelihood of holding recall elections after the 2010 municipal elections. The first two models confirm that the greater the party membership of the electorate in the political parties, the greater the likelihood of holding recall elections. Even though Peru is a country with a low level of political party institutionalization, it seems that party membership of a local electorate is an important variable in explaining recalls. Citizens in more politically active municipalities use the recall mechanism more often, which is quite logical as they are more interested in politics and are more easily mobilized. Local political leaders may use their members as a resource to obtain a sufficient number of signatures to initiate the recall procedure. These findings are in line with Whiteley’s (2009) research on party membership and mobilization. Whiteley (2009) finds that party membership at the aggregate level is a significant variable for the prediction of participation including mobilization for signing petitions. At the same time, in line with the elite mobilization theory, political leaders try harder to initiate a recall if the election results of the municipal elections are close. This supports the first hypothesis.

Blank votes are statistically significant in the first two models and in all elections since 1998 that are included in the correlations. The more blank votes there are, the lower the likelihood of holding recall elections. However, this is not true in the case of null votes. Null votes do not show significance in the first two models. These models, therefore, confirm that these may be distinct tools in the political system. Peruvian voters that have the potential to mobilize do not necessarily want to cast blank votes in municipal elections. However, voters may make a mistake during their voting, invalidating their votes and making them null or they may possibly feel more dissatisfied with the overall political system. Null votes are not statistically significant to predict the likelihood of holding recall elections. Voter errors could be explained by socioeconomic variables (mainly education), which is controlled in the models by the HDI variable. On the other hand, Driscoll and Nelson (2014) came up with the finding that voters cast blank votes because of political apathy in Bolivia. In contrast, Peruvian blank votes are associated with higher mobilization of citizens for holding a recall election in municipalities. It would seem that under compulsory voting, fewer blank votes within the electorate can predict greater engagement in politics in the form of recall elections. The higher number of invalid votes is often linked with higher dissatisfaction in politics and is also connected with party competition (Kouba & Lysek 2019). These models therefore confirm that a higher number of intentional blank votes increases the likelihood of recall elections because a high number of blank votes is likely connected with greater dissatisfaction and interest in politics. Therefore, a highly dissatisfied electorate with more blank votes is not actually interested in the recall procedure. This supports the second hypothesis.

Table 2.a Logistic regressions and Peruvian recall elections

Note:Standard errors in parentheses, *p <0.05, **p <0.01, ***p <0.001

Source: Author

Table 2.b Logistic regressions and Peruvian recall elections

Note:Standard errors in parentheses, *p <0.05, **p <0.01, ***p <0.001

Source: Author

The first and second models show that the smaller the difference between the first and the second party, the more likely it for recall elections to be called. So far, researchers (Holland & Incio, 2019; Tuesta Soldevilla, 2014; Welp, 2016) have considered political competition in the municipality to be one of the most important factors in explaining recall in Peru. I too confirm these conclusions. The difference between the first and the second party after the municipal elections is key to explaining recall, as is the ENP. However, in contrast, the lower the ENP, the greater the chance for holding recall elections. If support is concentrated in a few parties, there is no doubt that it is easier to agree and coordinate together and obtain the necessary number of signatures to hold recall elections. In municipalities with a large number of parties, recall organization is much more complicated. Also, as shown in the Appendix, I find a statistically significant correlation between competitiveness and the holding of all recall elections for all elections since 1998.

So far, the hypotheses have concerned the probabilities of holding recall elections. I now turn to variables that were assumed to influence the removal of a mayor. This is not the same as holding recall elections. For the successful organization of recall elections, it is necessary to mobilize and obtain 25 percent of the signatures of the electorate. For the successful removal of a mayor, he must be judged by the citizens and not only by the electorate who initiated the recall procedures. This is examined in models three and four. Unfortunately, as in previous models, all variables are only available for 2010 and beyond. However, all variables from 1998 that were not included in the models are listed in Table 5 of the Appendix.

Concerning socioeconomic variables, municipal development has no effect on the likelihood of holding recall elections and the recalling of a mayor. The HDI alone was used in the regressions, which was highly correlated with the other variables based on which this index is composed: life expectancy, percentage of people with secondary education, average years of education and family income per capita. None of these variables reached significant correlations in any elections from 2002 onward; some of them are only statistically significant in certain elections, but since this minimal correlation changes across the election, they cannot in any way be considered significant. By including the HDI variable in all models, where all the variables are controlled, it does not reach significance. Therefore, the municipality and the education levels of local citizens do not affect the likelihood of holding recall elections or whether the mayor is removed.

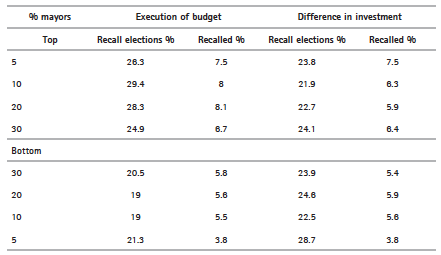

The most important question for supporters of a recall is whether we can consider the recall to be an accountability mechanism. It is very difficult to support this based on the recalls after municipal elections in 2010. The budget execution variable does not reach significance in any of the models, which is also the case for the variable examining the difference between the number of investments in the mayor’s first year in office with the previous two years. Table 2 also shows performance comparisons in percentiles. Five percent of the worst mayors in terms of budget execution faced recall elections in 21.3 percent of cases but they were recalled only in 3.8 percent of cases. In contrast, 5% of the best performing mayors were recalled in 7.5 percent of cases. Something similar is true for a variable called difference in investment, which should be crucial for citizens as it can be used to compare the periods and see the investments with their own eyes. Yet, the result is the same: 5% of the worst mayors were recalled only in 3.8 percent of cases, while 5% of the best mayors were recalled in 7.5 percent of cases.

The third hypothesis is therefore refuted because after municipal elections in 2010, the likelihood of removal in initiated recall elections for poorly performing mayors was not greater. Unfortunately, it is not possible to examine this finding for previous years due to insufficient data. These conclusions confirm what other researchers have suggested in previous literature (Tuesta Soldevilla, 2014; Welp, 2016). Overall, findings in relation to recall elections in Peru are not what would be expected according to classical economic theory, in which voters reward the incumbents in good economic times and punish them in bad times (Lewis-Beck & Stegmaier, 2008). In Brazilian municipalities, Sakurai and Menezes-Filho (2008) find that spending money is directly related to a mayor’s future success and is therefore seen as a form of accountability. However, the worst performing Peruvian mayors are not punished any more than the better performing ones. Thus, in the case of Peru, these findings are an important contribution to the literature.

But how can we explain the fact that the mayor is successfully recalled? If the organizer is a politically experienced person, this increases the chances of successfully recalling the mayor in the third and fourth model by about 80 percent12 compared to when the organizer never ran for election prior to recall elections in 2012 and 2013. Table 6 of the Appendix offers descriptive statistics based on organizers’ varying electoral experiences. For example, it shows whether organizers ran in the 2010 municipal elections or any other. It also examines whether the organizers previously ran for the office of mayor. In all cases, the organizers with electoral experience successfully removed mayors more often than organizers without electoral experience. These findings support the fourth hypothesis. Tuesta Soldevilla (2014, p. 22) suggested in his research that the linkage between an organizer’s party and electoral history is an important variable based on which to understand the recall procedure. I too confirm that it is a significant predictor of a successful recall. It seems that a person that is more engaged in politics is able to both convince enough citizens to recall a mayor and to organize the process. These findings follow Whiteley’s research (2009) of 36 countries to some extent. By using the multilevel model, he finds that at individual level, being a party activist, member or ex-member of a party increases civic participation and engagement in politics. I add to his conclusion, the new insight that organizers with electoral experience are more successful in recalling mayors than unexperienced organizers.

A greater number of null votes increases the likelihood of the successful removal of a mayor. In this case, even though blank votes go in the same positive direction as null votes, this variable does not reach statistical significance. After controlling socioeconomic variables (such as education within the HDI) that could have an influence on an involuntary voter error. It seems that null votes better explain voters’ dissatisfaction in municipalities, which they manifest during recall elections in removing a mayor. As I mentioned in the theory section, most studies do not differentiate between blank and null votes. The results of this study show that there may be good reason to distinguish between these two forms of invalid votes in future research.

Only one other variable is a statistically significant predictor for successful recall and that is the percentage of votes in the preceding municipal elections. Mayors who have won more votes in the preceding municipal election had a more secure position during successfully initiated recall elections.

The result of the regression shows that the municipalities that experienced some irregularities13 during the 2010 elections were over 120 percent more likely to hold a recall than municipalities with no problems. This is undoubtedly connected with the great political competition in municipalities, in which the electoral contest can sometimes exceed what is allowed. The turnout did not significantly explain the likelihood of holding recall elections. In this case, voter turnout is not a variable that would increase the likelihood of holding recall elections.

Financial transfers per voter appear to be relevant in the first two models to explain holding recall elections. The amount of financial transfers is mainly related to the size of the municipalities if the other variables are controlled; thus, the holding of recall elections is not more frequent in municipalities with higher financial transfers by the state per voter. The size of a municipality’s electorate is a statistically significant variable in the first two models and this is not surprising. Indeed, this is consistent with previous research (Tuesta Soldevilla, 2014; Welp, 2016). In smaller municipalities, it is easier to obtain the necessary number of signatures to organize a recall.

The young candidates variable is not statistically significant in any of the models and the young mayor variable is not statistically significant in the regression models. The gender of mayors and the gender of candidates in municipal elections are not statistically significant variables for explaining why a recall may be initiated. Although there is a positive relationship between a female mayor and the probability of recall elections, this does not reach statistical significance in any of the models and nor does political membership in APRA.

The experience with the recall variable is statistically significant in the municipality itself and in the province. For every experience with recall elections (between 1997 and 2010) in a municipality, in the first two models, the chances are increased by about 50 percent that there will be recall elections after the municipal elections in 2010. This implies that the recall cannot be considered a tool that would be used occasionally in municipalities and serve as a warning to politicians. On the other hand, if a municipality has already experienced a recall, it is more likely to use it again than a municipality without this experience. At the same time, the experience with this mechanism in the province shows that it reinforces awareness of this possibility and increases the likelihood of holding recall elections. Also, if the mayor was incumbent, it is positively associated with holding recall elections, but not significantly so.

Conclusion

What is the evaluation of Peruvian recall elections from 2001 to 2013? Recall cannot be described as a tool that would increase trust in the political system and parties. Peru is one of the countries with the least trust in its political parties, its democratic system and administration of municipalities in all of Latin America (Carrión, Zárate, & Zchmeister, 2015). The possibility of recall elections, which should give citizens more power to control politicians, has not changed this reality. By holding recall elections, individuals primarily seek to gain power and so the recall cannot be described as a tool of civil control. These conclusions are based on the fact that the variables describing the mayor’s performance in office were not relevant for explaining the likelihood of holding a recall election or, especially, his removal. In contrast, party membership, the number of blank votes and political competition do predict the likelihood of recall elections in Peru.

The findings regarding party membership are an important contribution. Political parties have a number of functions and are an important part of the political system, and therefore the weakness of political parties can have a considerable impact on the functioning of the political system. Political scientists have long analyzed European political parties; however, within the field of political science, studies outside this region are being encouraged (Heidar, 2006, p. 312). Today, the phenomenon of political parties in Latin America has yet to be sufficiently explored (Ribeiro & Locatelli, 2018, p. 4). As such, this paper is a positive contribution to the current literature on the “black box” of party organization (Levitsky, 2001).

In the case of successfully initiated recalls, only two other independent variables were important in explaining the removal of a mayor when the recall election was held. The first variable is logical and represents the percentage of votes in the previous municipal elections. The mayor who won with fewer votes would have fewer supporters, thereby reducing the likelihood that he will succeed during the recall election. The second variable involves the organizer of the recall procedure. If the organizer ran in the past elections, the success rate of the mayor’s removal increases. Similarly to the previous variable, this variable too shows the importance of political experience.

Future research should continue on in the direction of this article and examine the influence of party membership at local level and researchers should examine the blank and null votes as separate variables. In the future, when there is more data on recalls, it would be interesting to see whether this tool can truly improve accountability.