Introduction

Since the turn of the century, development research and practice has been prioritizing people and their quality of life. This has marked a rather significant move from the conventional perspective on development based on opulence or command over resources. Such a momentous move can, in no small measure, be attributed to the influential work carried out as part of the Human Development paradigm, which has become a persuasive alternative approach to development (Alkire & Deneulin, 2010). This is illustrated by the authoritative Human Development Reports issued by the United Nations Development Program as well as by a growing body of work both academic and policy-driven.

Although multiple scholars from different disciplines have contributed to this paradigm, perhaps none has done so more than Nobel Laureate Amartya Sen and his Capability Approach (henceforth CA). Indeed, until 2010, it was admitted that Human Development and the Capability Approach were so close that any attempts to discriminate them would virtually amount to a distinction without a difference. As Alkire (2010, p. 22, emphasis in the original) states “[...] there is no consensus as to a conceptually clear distinction between human development and the capability approach, nor is it obvious that such a distinction is useful or required.” Hence, although some features that tell them apart have been identified since then, this paper builds on the CA as it continues to be, by far, the main influence of the Human Development paradigm and, importantly, contributions to the former, will also contribute to the latter.

The CA is characterized by multidimensionality and diversity (Garcés, 2020a). The focus on multidimensionality in people’s lives places those aspects that are intrinsically valuable for human beings at the locus of attention. The emphasis is on the plural, there are multiple dimensions that are important for a person (e.g., being healthy, well-nourished, employed, etc.). There are multiple lives that a person can value and may choose to lead (Sen, 1992). Thus, development is about expanding people’s meaningful choices. The emphasis on choice highlights the importance of freedom for the approach, which has been called ‘freedom-centered’ (Sen, 1999). At the same time, it recognizes that opulence is important but only instrumentally, to the extent that it can help individuals reach intrinsically valued things (Sen, 1985). Therefore, the CA neither underestimates nor overestimates the significance of pecuniary indicators. It factors them in the analysis of social states as only instrumentally relevant factors. An illustration of this can be attested in the Human Development Index, a composite index to assess nations’ level of development, consisting from its inception of three relevant dimensions: health, education, and standard of living.

As for diversity, the CA recognizes human plurality. In addition to people having many legitimate goals that they can pursue, the capabilitarian perspective also stresses the fact that they are likely to require different amounts and types of resources in order to meet those goals. This is due to how personal and contextual characteristics affect the conversion of resources (instrumentally valuable things) into quality of life (intrinsically valued things) (Sen 1999; 2004).

Converting resources into valued states requires choice and reason (Garcés, 2020b; Garcés-Velástegui, 2020). These are the elements composing the CA’s notion of human agency. Sen (1999) regards the latter as bringing about change and judging this change and its underlying preferences. While the first element points to the significance of freedom, the second signals the relevance of rationality. Both, as part of one notion, suggest the dynamics and interdependence of the component of agency. Thus, by placing people at the locus of attention, the CA provides an account of human beings and their agency, which is why the framework has also been said to be ‘agency-oriented’ (Sen, 1999).

The capabilitarian perspective’s underscoring of the importance of rationality can hardly be overstated. Criticizing the axiomatic convention, it redefines rationality as subjecting choices and preferences to critical scrutiny (Sen, 2002). Although people can analyze their values, reasons, and actions, this does not mean that the result is adequate, let alone optimal. In fact, it is often suboptimal. Despite their introspection, people can systematically fail to obtain their reflected-upon objectives, goals, and lives they value. That is, human fallibility matters, but the CA has omitted this in its account of human agency. The CA’s conventional account, however, has omitted an elaboration of non-reflective action as well as failures in both reflective and non-reflective action (Garcés-Velástegui, forthcoming).

Behavioral economics (BE) can fill this void. BE describes actual human behavior (see e.g., Oliver 2013; Shafir 2013; Bhargava & Loewenstein 2015; Chetty 2015) by exploring the systematic ways in which people divert from the conventional rational model. As such, much of BE focuses on people’s failures to achieve their own goals (what is valuable as defined by them) in general and well-being ones in particular. Accordingly, the coincidence with the CA seems to be twofold. First, it privileges people’s freedom and their role in determining their valued objectives and lives. Second, in that assessment, it also prioritizes people’s well-being or quality of life. Adding BE’s insights to the CA, therefore, enriches the framework’s personal and contextual factors (GarcésVelástegui, forthcoming).

An elucidation in terms of what this means for policy-making, however, is lacking. Because both are quintessentially policy-oriented frameworks this discussion is warranted. What are the implications of behavioral findings for human development policy? What would behavioral human development policies look like? Do all behavioral insights resonate equally with the CA and can they further human development in the same way?

To propose plausible answers, this paper is divided into three further sections. At the outset the CA, its evolution, and scope regarding its account of rationality is introduced. A discussion of BE and its approach to decision-making follows. Next some implications for human development policy are presented. The final section offers some concluding remarks.

I. The Capability Approach: freedom-centered and agency-oriented

The CA is a conceptual framework for the study of development. That is, it is neither an explanatory theory of development, positing the relevant dependent and independent variables and the logical pathway to a development outcome, nor is it a metaphysical discussion regarding the philosophical status of development. Instead, this perspective advances a descriptive and normative proposal about what development should be. This section is devoted to fleshing out that argument following Amartya Sen’s original and seminal work as well as the main contributions made to it.

The CA focuses on people and their quality of life to evaluate social states. As such, it provides an account of human beings3. In so doing, it places the things that make life worthwhile at the center of attention. Thus, it regards opulence as important but only instrumentally, to the extent that it enables us to obtain intrinsically valuable things (see e.g., Sen, 1990; 1992; 1999). The latter are referred to as capability and functionings. The approach also recognizes the diversity characterizing people and contexts by its attention to conversion factors and it expands on the relevant motivations people may have, which are captured by agency and well-being. The following discussion addresses each of these aspects.

A. Freedom-centered: Functionings and Capability

Functionings and capability denote the intrinsically valuable aspects of life. As such, they constitute the evaluative space where the assessment of social states ought to take place. Functionings highlight people’s actual functions, what they do and are. Thus, they are the beings and doings that people value and have reason to value (Sen, 1999). They are achieved states or duly considered valuable types of life (Sen, 1993). That being so, a person’s achievements can be seen as the vector of their functionings (Sen, 1992). Consequently, they are constitutive of a person’s being (Sen, 1990) and, what is more, life can be regarded as the combination of several interrelated beings and doings (Sen, 1992).

The valued functionings may vary from elementary ones, such as being adequately nourished and being free from avoidable disease, to very complex activities or personal states, such as being able to take part in the life of the community and having self respect (Sen, 1999, p. 75).

The emphasis on the plural signals the CA’s move from opulence and single indicators to the recognition of the incommensurability of the intrinsically valuable things in life. Therefore, the approach advances multidimensionality. The same applies to the opposite of functionings, i.e., deprivations or disadvantages.

Capability, in turn, encompasses all potential functionings from which a person can choose (Sen, 1999). Its name comes from their denoting people’s capability to function (Sen, 1992). In this sense, it captures the notion of freedom, entailed by the possibility people have to choose from different lifestyles regarded as valuable after reflection (Sen, 1993). Hence, both a person’s doings and beings and the freedom to choose them constitute a valuable life (Crocker & Robeyns, 2010). Sen (1999) suggests that development ought to be assessed in the space of capabilities and has redefined development as freedom.

The above notwithstanding, both functionings and capability are important for the approach. The focus on capability means that besides outcomes, processes also matter (Sen, 1997). Given the assessment of a social state, it makes a difference if it is the product of imposition or of choice. Moreover, the actual exercise of freedom is important and, therefore, attention to actual outcomes and functionings is necessary. That is, even when the possibility of choice is available, it is indispensable to know how it is exercised. To address this, Sen (1997) introduces the differentiation between ‘culmination outcomes’ and ‘comprehensive outcomes’. While the former focus only on the result, the latter also encompass how the result is reached. The CA regards the improvement in people’s lives as an expansion of their freedom. Thus, development is about expanding people’s choices in all dimensions of life (Haq, 1995).

The stress on a person’s various possible valued, reflected-upon types of life underscores the CA’s focus on human plurality. There is a myriad of legitimate lives that a person can lead and, in fact, the opportunity to choose is relevant to well-being (Sen, 1999). This has been referred to as inter-end variation (Sen, 1992). Being a parent or not, observing a religion or not, pursuing a career or not, practicing a sport or playing an instrument or not are a few examples of legitimate considered ends. As in the case of functionings, there are multiple dimensions that can be so valued. And, just as the presence of freedoms is relevant, so is their absence, referred to as capability deprivations or unfreedoms.

In sum, while functionings are achievements, capability is the freedom to achieve. “Freedom can be distinguished both from the means that sustain it and from the achievements that it sustains” (Sen, 1992, p. 86, emphasis in the original). At the same time, Sen (1999) points out that different capabilities can be related to each other. Expanding some freedoms may lead to the expansion of others. Thus, freedom plays a constitutive and instrumental role in development (Sen, 1999).

More recently, the capability framework has been enriched with additional insights. Wolff and de-Shalit (2013) have explored an interdependence among functionings and among disadvantages. There are important achievements that can lead to the improvement of others. These are referred to as ‘fertile functionings’. Having disposable income is a telling example as it can lead to other achievements. Less evident examples are also possible. Humor, for example, can be a functioning that improves a person’s social abilities from school to the office environment, augmenting their likelihood of success in each, and leading to a better quality of life, in societies that value humor (Wolff & de-Shalit, 2013). By the same token, there are deprivations that can aggravate existing ones. These are known as ‘corrosive disadvantages’. The lack of disposable income can be such a deprivation because its absence limits the consumption of relevant goods and services for a person’s quality of life. Another, less conspicuous, illustration is parents’ education since less educated parents tend to have a poorer vocabulary and talk less to their kids, thereby reducing the latter’s school performance, possibilities for higher education, and job opportunities (Wolff & de-Shalit, 2013).

Finally, freedom is conceived broadly within the approach. Sen (2009; 1988) points to the distinction between opportunity freedoms and process freedoms. While the former can be associated with the notion of positive freedoms, as in ‘being free to’, the latter can be linked to negative freedoms as in ‘being free from’, in the libertarian tradition. Both are relevant to development (Sen, 1999). Sen (2009) stresses that the capability perspective regards substantive, effective, or opportunity freedom widely, of course focusing on choice (opportunity) but also including process. Nonetheless, he also acknowledges that the CA accounts for the former much better than it does for the latter (Sen, 2004).

B. Conversion factors: personal and contextual

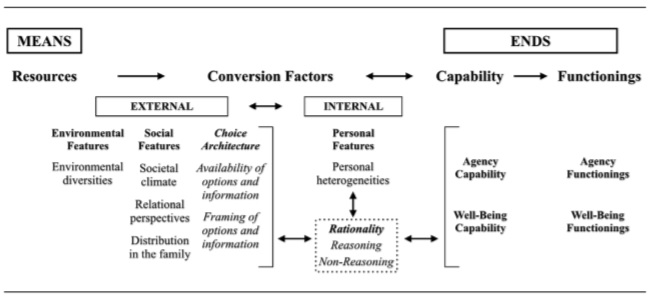

What is more, the CA recognizes that the translation from resources to capability or functionings is not direct but mediated. Sen (1999) identifies the following conversion factors: i) personal heterogeneities; ii) environmental diversities;iii) variations in social climate; iv) differences in relational perspectives; and, v) distribution within the family. These can be summarized as characteristics of the individual as well as features of the context, whether environmental or social, that can affect that conversion (see Figure 1). While personal characteristics can be exemplified by age, gender, ethnicity and civil status, social ones may be illustrated by religious practices, societal norms and family customs, and environmental ones by rurality, region (coast/mountain/jungle), soil fertility, availability of basic public services, and probability of droughts. These are also referred to as internal and external conversion factors, respectively.

If the attention to multidimensionality and diversity entailed by the CA’s recognition that there are various legitimate types of life is a first move towards human plurality, the addition of conversion factors, consolidates this position. The latter has been referred to as inter-individual variation (Sen, 1992). This addition is significant given that different people in different contexts may require different quantities and qualities of resources to reach certain levels of achievement. For instance, a pregnant woman, someone with a disability or terminal illness, or someone whose labor is physically taxing require more resources (for nourishment, medicine, etc.) than people lacking these personal characteristics. The challenge is compounded by the addition of different contexts, as resource requirements can vary for those individuals depending on whether they live in rural or urban areas and whether they have immediate access to public services (health).

Inter-end and inter-individual variations are closely related. A person’s actual freedom to lead their reflected-upon, valued types of life depends on two factors, namely their goals, and their power to convert resources into the meeting of those goals (Sen, 1992).

As illustrated by the above, the focus on Sen’s discussion has been on conversion factors as constraints for the achievement of relevant outcomes. This has been expanded in recent contributions to include their conception as enablers as well (Hvinden & Halvorsen, 2017). Conversion factors, therefore, serve the purpose of establishing the necessary nexus between agents and structures in order to explain the dynamics between them. What is more, conversion factors also interrelate, particularly individual features with social ones, which can help explain unexpected outcomes (Hvinden & Halvorsen, 2017).

Source: Garcés-Velástegui (forthcoming)

Figure 1 Illustration of the CA’s movement from means to ends incorporating latest contributions

C. Agency-oriented: Well-being, and Agency

Concerning motivation, the CA introduces two categories: well-being and agency. Well-being refers solely to personal welfare (Sen, 1993). It captures the inducement related to self-regarding goals and individual wellness (Sen, 1992). Being healthy, literate, or able to elect and be elected, or earning the same salary for the same job regardless of gender, ethnicity or another characteristic are some examples.

Agency is a broader concept and denotes the totality of a person’s motivations and goals. It conveys the idea of “what a person can do in line with his or her conception of the good” (Sen, 1985, p. 206). That is, it encompasses both self-regarding and other-regarding objectives (Crocker & Robeyns, 2010). Some illustrations are: participating in philanthropy and volunteering, being able to donate blood/organs, or to demonstrate against climate change.

Moreover, Sen (1999, p. 19) regards agency “[…] in its older – and ‘grander’ – sense as someone who acts and brings about change, and whose achievements can be judged in terms of her own values and objectives, whether or not we assess them in terms of some external criteria as well.” In this sense, agency is valuable in and of itself. Associating it to the capability of political participation, it has been argued that the value of agency is threefold: i) intrinsically, instrumentally, and constructively (Alkire, 2009). Intrinsically, by denoting people’s ability to control their environment to pursue their considered goals, agency enables people to be in control of their lives. Instrumentally, agency can be valued insofar as it enables people to enjoy capabilities and functionings. As in the case of capabilities and functionings, free agency “[…] contributes to the strengthening of free agencies of other kinds” (Sen, 1999, p. 4). Constructively, agency entails judgment, not only choice and, as such, it permits the assessment of preferences and values (Crocker & Robeyns, 2010). This is particularly important for the inevitable selection of relevant capabilities and their ranking.

What is more, the evaluative space and motivations are deeply interrelated. This means that capabilities and functionings can be expressed in both well-being and agency, beyond well-being (see Figure 1). Regarding well-being, an individual can achieve functionings or types of life that are exclusively and solely related to their wellness. At the same time, the vector of those potential functionings, their capability can be related solely to them as well. Therefore, both well-being functionings and capabilities are possible. Apropos of agency beyond well-being, i.e., other-regarding goals, an individual can achieve doings and beings that do not advance their own welfare. Sen (1992, p. 56) has posited that: “A person’s agency achievement refers to the realization of goals and values she has reasons to pursue, whether or not they are connected with her own well-being. A person as an agent need not be guided only by her own well-being, and agency achievement refers to the person’s success in the pursuit of the totality of her considered goals and objectives.” Further, the vector of all potential such functionings, would depict their capability. Thus, there can be agency functionings and capability as well.

The differentiation between agency and well-being is momentous. In fact, although they are likely to move in similar directions, this distinction is useful to account for the tension that may ensue between goals related to each. The pursuit of other-regarding objectives, say an organ donation, may lead to an increase in agency achievement but also a decrease in well-being achievement. Additionally, the distinction can highlight the interdependence between the categories (Sen, 1992). First, well-being is a motivation that a person can have as an agent. Second, achieving other-regarding goals can certainly contribute to an agent’s well-being and, likewise, failure to achieve them can prove detrimental to it.

Furthermore, it has recently been pointed out that the CA’s very notion of agency challenges the dominant approach to human conduct, rational choice theory, turning rationality into reasoning. (Garcés, 2020b). Sen (1977) has stated that the axiomatic rational model renders people ‘rational fools’. This is related to the second part of the approach’s concept of agency, dealing with the agent’s ability to judge their values and objectives, a relatively much less explored aspect of the notion. This points to the relevance that rationality has for the capability perspective. In this sense, Sen (2002, p. 4) has opposed the convention and proposed an idea of rationality that is much closer to human experience and the CA:

The broad reach [of reason] entails the rejection of some widely used but narrowly formulaic views of rationality: for example, that rationality must require following a set of a priori “conditions of internal consistency of choice” or “axioms of expected utility maximization,” or that rationality demands the relentless maximization of “self-interest” to the exclusion of other reasons for choice.

In his later work, Sen (2009, p. 180, emphasis in the original) specifies: “[...] rationality is primarily a matter of basing —explicitly or by implication— our choices on reasoning that we can reflectively sustain, and it demands that our choices, as well as our actions and objectives, values and priorities, can survive our own seriously undertaken critical scrutiny.” Against the convention, this means that for the CA de gustibus est disputandum; that is, preferences and values are not assumed but must be subject to study. Consequently, in contrast to the dominant rational agent, the CA’s agent has been described as a reasoning agent (Garcés, 2020b).

II. Behavioral economics: humanity and its fallibility

Behavioral economics builds on the dominant model of rational decision-making but makes important objections. Before addressing the latter, it is worth introducing, however briefly, the conventional approach: rational choice theory (RCT). Even though no consensus has been reached regarding what full rationality is (Wittek et al., 2013), Camerer et al. (2003) have found at least three elements of agreement: i) individuals have well-defined and constant preferences, and through their choices seek to maximize them; ii) individuals’ preferences indicate all the real costs and benefits of every option available, to the best of the their knowledge; and, iii) if uncertainty occurs, individuals have both well-informed beliefs about how it will resolve itself and the capacity to update them with new information, which is added to their probabilistic assessments. In this sense, RCT furnishes a model of what rational decision-making is and should be. Put otherwise, it offers a normative rather than a descriptive framework for human conduct.

Although conceived within the field of economics, RCT became the main approach to account for human decision-making during the twentieth century in other disciplines as well. The positivist context intended to rid the study of society of value judgements with a mathematically-inspired view of the world, led to what later became neoclassical economics. Privileging elegance and parsimony over realism, the focus was placed on formal theorizing and the reduction of social complexity to axiomatic assumptions (Corr & Plagnol, 2019). So influential was this approach that it was believed to apply to all human behavior. Gary Becker (1976, p. 8) stated: “I have come to the position that the economic approach is a comprehensive one that is applicable to all human behavior.”

RCT has been subject to strong critique and BE is not an exception. However, BE does not throw the baby out with the bathwater and instead of full rejection, it employs the rational model as a yardstick against which to assess human decision-making. In this sense, there are, at least, two important challenges. First, BE abandons rational choice theory’s normative assumption of optimal behavior, focusing instead on a descriptive account of human conduct. Second, that descriptive perspective focuses on how humans actually behave, focusing on their fallibility.

A. Decision-making: individuals and context matter

BE recognizes that humans in actuality fail to conduct themselves in accordance with the axioms of full rationality assumed by mainstream economic theory, i.e., neoclassical economics (Dawnay & Shah, 2005). This recognition is based on sound, mostly experimental, research. These divergences from the standard model are referred to as misbehaviors instead of irrationalities, in light of the negative connotations of the latter (Thaler, 2015). They ensue because people’s decision-making takes place via a process consisting in two systems, each of which can fail. One is automatic and the other is reflective (‘rational’) (Thaler & Sunstein, 2009).

Whereas system 1 is engaged automatically, is in charge of non-reasoned action, works effortlessly, and involuntarily, system 2 operates only when required, is responsible for reasoned action, requires effort, and is deliberately engaged (Kahneman, 2011). S1 works sufficiently well most of the time, providing satisfactory outcomes. This suggests that, at best better outcomes are possible and at worst, outcomes can be counterproductive. Despite its capacity, S2 is not infallible either and can also produce sub-optimal outcomes. The use of S1 and S2 is a matter of degree, however, not an all-or-nothing situation. The power and effectiveness of S1 and S2 can change. Training them can improve their performance and other factors like age (childhood and elderliness) can diminish it. Cognitive skills and discipline are subject to betterment and can influence both. Indeed, the effort demanded by perfecting talents and abilities decreases as they are practiced (Kahneman, 2011), depending on personal features as well. The above notwithstanding, S2 can also fail and often enough, it does.

S1 and S2 are both necessary and complementary. While S1 is intuitive and impulsive, requiring minimum effort, S2 is conscious, reflective, and deliberate, demanding more energy. Beyond their differences, one commonality worth stressing is that both are prone to fail.

Failures in S1 and S2 frequently, and to varying extents, depend on the context in which the decision-making is performed, or its choice architecture. This is the setup or circumstances in which choice takes place. For example, different arrangements of the options available can induce different choices, which may or may not be optimal or even aligned with the chooser’s (longterm) preferences (Thaler & Sunstein 2009; Sunstein 2020). This means that for BE, decisions are embedded within a situation. Thus, actual behavior, and the systematic deviations from the rational model, are explained by personal biases and heuristics as well as the features of the context. That is, the environment in which choices are made also matters.

Significantly for policy-making, because choices are necessarily made in a context, deciding on the choice architecture is inevitable (Thaler & Sunstein 2009). Whether aware of it or not, ‘architects’ facilitate, or not, the attainment of people’s goals and the enhancement of their well-being.

B. Decision failing: individuals and context matter

Deviations from the rational convention have been referred to as ‘reasoning failures’4. The literature uses this term to cover failures in both S1 and S2, although reasoning is mainly performed by the latter. Although such an approach may be justified in light of the aforementioned fact that both systems are a matter of degree and subject to change, it seems more straightforward to talk about rationality failures to encompass both, so as to avoid confusion when failures in different systems can be clearly identified. The causes of these failures can be categorized into four types of limitations associated to: i) technical abilities; ii) imagination or experience; iii) objectivity; and iv) willpower (Le Grand 2008). Limited technical ability indicates the incapacity to assimilate and interpret information. Limited imagination and experience refer to the incapacity to foresee states of the world not lived or hypothetical, and one’s possible reactions to them (Le Grand, 2008). Limited objectivity refers to the incapacity to be impartial towards one’s view. Limited willpower indicates weakness of will. Information and experience, however, do not guarantee optimal outcomes in the long run.

Many of these limitations, biases and heuristics emphasize the fact that preferences and choices are not made in a vacuum but necessarily within a specific context. Human action takes place embedded in a situation. This context, or the circumstances and conditions surrounding choice, is referred to as ‘choice architecture’, and inescapably influences decision-making, whether deliberately set up or not (Thaler & Sunstein, 2009; Thaler, 2015). Because of this, and the fact that this architecture can be modified, much of BE’s contributions have sought to contribute to policy-making and address those failures (Sunstein, 2020; Vlaev & Dolan, 2009).

In terms of behavioral policy, the recent literature has made a distinction between nudges and boosts (Grüne-Yanoff & Hertwig 2016; Hertwig & GrüneYanoff 2017). Deriving from behavioral insights, both assume that people make decisions employing a limited number of heuristics and that whether they work or not depends on the characteristics of the environment in which the decision takes place (Grüne-Yanoff & Hertwig 2016). Additionally, nudges and boosts are both intended to change human behavior without resorting to conventional interventions; that is, neither using substantial material incentives nor resorting to coercive mandates. The difference, briefly put, lies in how they affect behavior. While nudges instrumentalize people’s cognitive limitations to influence their behavior, boosts expand people’s set of competences to induce theirs (more on this presently). In this sense, the distinction seems to be differentiating behavioral interventions roughly into those targeting S1 failures as ‘nudges’ and those aiming at S2 as ‘boosts’ (Garcés-Velástegui, forthcoming).

C. Behavioral agency: fallibility in multiple motivations

BE’s account of human behavior challenges the framework of full rationality and presents a description of how people actually act. This means that rather than establishing elegant axioms suggesting how people ought to act, and often do, to achieve optimal outcomes, BE acknowledges that human beings are fallible and founder in their pursuit of optimal welfare outcomes. These failures are systematic and, therefore, exploring them contributes to economic explanation and prediction. For BE, human beings are “plural, more and less reflective choosers, and multi-motivated” (Garcés-Velástegui, 2022b).

In brief, S1 makes suggestions to S2 which, under normal circumstances, are endorsed by it without adjustment or revision, turning impulses into voluntary action. Most of the time, this less reflective process dominates human action. Only when the situation demands it, S2 takes over. This complimentary interaction between S1 and S2 is efficient, leading to sufficiently good outcomes, but not necessarily optimal because people fail.

These have been referred to as reasoning failures, which can ensue due to personal limitations, and contextual features, or a combination thereof. Therefore, for BE, human action is embedded in a situation, which means that context and history matter. While perhaps the best illustration of the influence of context on human behavior is the inescapable ‘choice architecture’ (Thaler & Sunstein, 2009; Sunstein, 2020), history can be exemplified by the habits, talents, and skills, learnt (or not), which is related to inter alia their social norms, and culture. This exposes BE’s attention to human diversity.

The literature has added other-regarding goals as motivations orienting human action within BE. This is another challenge to the model of full rationality and its exclusive focus on the maximization of self-interest. For BE, this remains an important objective but not the only one. Egoistic as well as altruistic aims are increasingly being incorporated by the approach (Garcés-Velástegui, forthcoming).

III. Behavioral human development policy

People face important challenges in the pursuit of the doings and beings they value and have reason to value. Therefore, they often fail to lead reflected-upon valuable lives. As the CA stresses, these can be explained by internal and external features or conversion factors. Different people in different places need different quantities and qualities of resources to reach functionings or capability. BE aids to specify the factors affecting this translation by underscoring the role of rationality, an aspect recently highlighted within the CA (see Garcés 2020b; Garcés-Velástegui, 2020), and that of the context. The contribution could significantly expand the CA conceptual model (see Garcés-Velástegui, forthcoming). In particular, in accordance with the CA, BE suggests that many of the difficulties people have can be attributed to properties in both. Depending on the biases and heuristics people use (rationality or an internal factor) in their decision-making, and how stimuli is presented to them (context or an external factor), people can systematically fail to achieve doings and beings, and to enjoy freedom.

Hence, BE insights can contribute to the account of human agency provided by the capabilitarian perspective in its own project. By so doing, it can also aid the human development paradigm. In practical terms, the policy relevance of this merging can be usefully elaborated according to the three broad categories of policies that can be informed by BE: mandates, nudges, and boosts. Importantly, for this discussion, it is worth stressing that nudges and boosts are not necessarily “two models are not competing representations of heuristic-based decisionmaking, but apply to different kinds of heuristics” (GrüneYanoff, Machionni & Feufel, 2018).

A. Behavioral mandates for human development

Under the label of mandates, for current purposes, fall all interventions employing substantial material incentives or coercive legal instruments. Although BE has mainly influenced the use of alternative policies leading to the interesting proposition of libertarian paternalism (see Sunstein & Thaler, 2003; Thaler & Sunstein, 2003), this does not exclude the possibility of using behavioral insights for more traditional policies.

At their core, mandates establish an incentive, rewards, or punishment, in order to produce a particular behavior. Underlying these interventions is usually the conventional model of instrumental rationality, stressing the individual’s sole concern with the maximization of its utility and the calculation involved therein. Since BE uses the convention as a benchmark, its insights can be put at the service of these interventions as well.

Indeed, this is arguably the intuition behind one of the most widespread poverty-alleviating policies: conditional cash transfers (CCTs). In brief, they are monetary transfers provided to households under an income poverty line and paid upon verification of certain conditions, most often school attendance of children within the household and periodical medical check-ups of pregnant women as well as infants. By changing the situation through a substantial material incentive, the policy seeks to produce a behavior in beneficiaries that they would not otherwise engage in, despite it being in their own self-interest. It becomes a mandate for beneficiaries due to the condition with which they are obliged to comply in order to receive the transfer.

To be sure, this policy has been conventionally explained in terms of opportunity costs. Under normal circumstances (without the intervention), poor households cannot afford to invest in education or health since the little they have barely suffices to survive. The merits of this perspective notwithstanding, it does not exclude the presence of reasoning failures. It seems sensible to argue that not all beneficiary households are equal. Despite all falling under a poverty line, there are those that are closer to it and those that are farther, those that have more and those that have less vulnerable people (children, elderly, etc.). For those families that can afford to invest in education and health and still do not unless CCTs are implemented, an argument can be sensibly made on the basis of behavioral economics.

In this respect, although such interventions may be regarded as freedom restricting, in both the short and long term, people’s choices can be expanded, as the CA advances. Not only are education and health valuable things in and of themselves, these outcomes can lead to other opportunities for the exercise of substantive freedom and achievements as well.

Another relevant policy debated lately is the possibility of vaccination mandates to fight the spread of COVID-19. Governments are considering this policy to safeguard people’s well-being in light of some groups’ reluctance to get vaccinated on autonomy-related and other grounds. Behavioral economics can explain many of these positions as being based on reasoning failures. Based on such explanations, via a mandate, people’s health, welfare, and even life itself, can be prioritized at the expense of some freedom because it is compelling people to do something that is in their self-interest despite their refusal to deem it so.

B. Nudges for human development

Nudges are the first, and perhaps most famous, type of interventions inspired by behavioral economics that are intended to change people’s behavior without changing material incentives substantially or resorting to coercive legal instruments. They have been defined thusly:

[A] ny aspect of the choice architecture that alters people’s behavior in a predictable way without forbidding any options or significantly changing their economic incentives. To count as a mere nudge, the intervention must be easy and cheap to avoid (Thaler & Sunstein 2009, p. 6)

These interventions assume that people employ a limited set of heuristics in their decision-making and seek to steer individuals towards a given conduct through adjustments in the context in which decisions are made so as to trigger a specific heuristic strategy. In other words, “the nudge approach instrumentalizes these cognitive limitations to influence behaviour” (GrüneYanoff, Machionni & Feufel, 2018, p. 4). Heuristics, thus, are regarded as sufficiently stable so that changes in the environment consistently activate the same heuristic leading to the same expected behavioral changes. In fact, the initial relevant literature treated them as similar to optical illusions (Tversky & Kahneman 1986; Kahneman & Tversky 1996) that cannot be corrected despite one’s awareness of them. That is, heuristics are not easily changed and training to improve them can be difficult.

There are numerous successful illustrations of the use of nudges to increase people’s well-being. From the now famous ‘Save More Tomorrow’ program designed to increase the contributions people make for their pensions (Thaler & Sunstein 2009), to the warnings of various types (texts and images) on cigarette boxes, the goal is to harness a particular heuristic with each intervention on the environment to produce a predicted behavior.

Although such experiences have been conceived in developed nations, there is evidence from developing contexts as well (see e.g., Alpizar et al., 2020; Nelson, Partelow & Schlüter 2019; Sudarshan 2017). Some examples are Colombia’s pop-up messages to remind people to pay their social protection contributions online (Alm et al., 2019) and Ecuador’s ‘nutritional traffic light’ which alerts potential consumers about the levels of fat, sugar, and salt color-coding them so that red is high, yellow is medium, and green is low.

Consequently, since nudge interventions affect choice, they can lead to the achievement of reflected-upon valued doings and beings. This means, that complementary policies are advised to allow people to expand their own choices.

C. Boosts for human development

Boosts are the second, and perhaps lesser known, type of interventions inspired by behavioral economics seeking to produce a change in behavior employing neither a substantial change in material incentives nor coercive legal mandates. As its name suggests, “boosts have been characterized by their ‘goal of expanding (boosting) the decision maker’s set of competences and thus helping them to reach their objectives’” (Grüne-Yanoff & Hertwig 2016, p. 156).

Much like nudges, boosts also assume that people’s decision-making is based on a limited set of heuristics. However, there are also, at least, two important differences. First, boosts endeavor to produce a change in behavior by enhancing people’s competences; i.e., overcoming people’s cognitive limitations, instead of harnessing or instrumentalizing them. Second, rather than targeting exclusively the environment in which decisions are made, boost policies can also address the individual’s set of heuristics directly.

This being so, the relationship assumed between the environment and the heuristic is distinct for boost interventions. The environment, in this case, does not activate or trigger a heuristic. Instead, it furnishes the individual with informational cues leading them to select a heuristic from a repertoire (GrüneYanoff, Machionni & Feufel, 2018). If cues in the context in which the choice takes place do not match a given heuristic, people resort to their inventory of heuristics and select one that accommodates the situation more readily. Since the individual exerts agency in the selection of heuristic, rather than it simply being triggered, the assumption is that it is possible to improve that selection and learning of other heuristics via training. This is how boosts intervene on the person’s heuristic repertoire instead of on the environment.

The literature has suggested that simple accessible rules can be more effective to make sufficiently accurate assessments than more complicated, technical, or sophisticated training (see Gigerenzer et al., 1999). From stock exchange to food consumption, there is growing evidence of the benefits of such an approach.

For developed and developing nations alike, the main lesson seems to be that boost interventions can be effective when there is the possibility to teach simple rules of thumb or simple ways to train people to undertake complicated procedures. They improve people’s competence to make better choices in the pursuit of their own goals. For example, people’s financial decisions can ameliorate if they are taught simple financial and accounting rules (Drexler et al., 2014), and parents can improve the nutritional habits of their children by modelling healthy behaviors during family meals (Dallacker et al., 2019).

Accordingly, given that, much like nudges, boost policies affect choice, they can contribute to people leading the lives they value and have reason to value. At the same time, however, since boosts can expand the heuristics available for individuals, they seem to be expanding the choices people can make. Put otherwise, such interventions can help people to reach both ends advanced by the CA: functionings and capability.

D. CAand BE-inspired policies: Freedom and Achievement

As the discussion in this section suggests, there is considerable coincidence between behavioral public policies and human development policies, based on the CA. Both place freedom and achievements at the locus of attention. On the one hand, the CA has redefined development as freedom and, since development proposes ends as well as means, it suggests that freedom is the end as well as its principal means (Sen 1999). Functionings, whether as well-being or agency more broadly, can depend on the exercise of freedom and be a consequence of it. Policies inspired in the CA, therefore, can enhance capability, and thereby functionings, or functionings alone (Sen 1992). The CA admits that functionings can be improved directly, but such policies would be inferior to capability-enhancing ones as they overstep people’s freedom (Sen 1999). On the other hand, behavioral public policies are mindful of freedom and highlight the extent to which it may be curtailed by welfare promoting interventions. They do so by focusing on the exercise of choice in the pursuit of well-being (whose definition seems closer to the CA’s notion of agency functioning since it increasingly encompasses other-regarding goals), as defined by people themselves, and also by exposing why people often settle for secondary outcomes. Well-being, thus, can be induced by suggesting effective ways in which people can be helped to reach their goals, preferably without hurting their freedom.

In this sense, BE makes a policy-relevant contribution to human development. It can be argued that whereas the capabilitarian framework proposes what development is, behavioral insights clarify and classify some pathways on how to attain it. Should freedom, or the expansion of meaningful choices, as proposed by human development, be enhanced, then boosts are the safest bet. If there is levelled concern between freedom and achievements in human development, nudges are most likely to reach that balance. When achievement is prioritized in human development, even at the expense of some freedom, then mandates become an option. As the discussion above suggests, however, these alternatives are not necessarily mutually exclusive. There might be issues and circumstances for which they can be complementary and different combinations can prove useful. Ultimately, the policy choice is political. It is up to the people in the public sphere to decide, and this is yet another aspect in which the CA and BE would find agreement. The discussion elaborated here can prove useful in that debate by shedding light on the implications of different behavioral policies for human development.

Conclusions

The Capability Approach is a normative framework for the assessment of social states that emphasizes people. As such, it has proven most influential for development research and policy around the world. Perhaps the best illustration is the Human Development paradigm, inspired by it. By placing people and their quality of life at the locus of attention, it has provided an account of human beings and their agency. This perspective highlights the relevance of freedom (manifested in choice) and rationality. Importantly, the CA redefines rationality as the critical scrutiny of one’s values, preferences, choices, and actions. Thus, it moves beyond the conventional axiomatic rational model that assumes optimal behavior and results. The CA’s notion of rationality as reasoning, however, does not mean that people are infallible. Indeed, people often fail to fully reach their considered goals, settling instead for secondary or good enough outcomes. Hence, despite its advantages, an account of people’s decision-making failures to lead the lives they value and have reason to value is missing. This seems rather important for a freedom-centered and agency-oriented approach aimed at enhancing people’s lives in terms of the expansion of their meaningful choices.

This paper has proposed behavioral economics to complement the CA. BE challenges the dominant rational model without fully rejecting it. Building on the convention, BE explores the deviations from it in actual human behavior. That is, it provides a descriptive rather than a normative account of human conduct. As such, it identifies the way in which people fail to reach their objectives. According to BE, decision-making uses two systems: System 1 is in charge of automatic, reflexive, and effortless action, while System 2 is responsible for deliberate, reflective, and effortful acts. Although they efficiently interact and can improve (or decay), they are also prone to failure. This is because, rather than pursuing optimal outcomes, people are most often satisfied with getting by (inferior choices) and thus use biases and heuristics, or shortcuts. These deviations from optimality are systematic, and therefore, furnish BE with considerable explanatory power.

The CA and BE are intrinsically policy oriented. The CA advances development in terms of freedom and regards functionings, whether in well-being or agency, as both a part and a consequence of it. Human development policies, therefore, can favor capability or achievement, although those that promote the former are superior. Behavioral public policy, in turn, has proposed ways in which interventions can help people reach their well-being goals (here increasingly conveying an idea closer to the CA’s notion of agency functioning because it increasingly also covers other-regarding goals), as defined by them, many of them respecting their autonomy and freedom.

Consequently, not only do BE and human development share an interest in freedom and well-being, the former makes a policy-relevant contribution to the latter. While the capabilitarian framework proposes what development is, behavioral insights clarify and classify some pathways on how to attain it. Three main behavioral policy types are of interest: mandates, nudges, and boosts, each of which proposes a different equilibrium between freedom and well-being. Mandates, being of obligatory compliance, tip the scales in favor of well-being, restricting freedom the most. As such, they are relatively farthest from human development goals. Nudges, as they avoid the elimination of options and changes in economic incentives but using people’s biases to steer their decision-making, strike a balance between well-being and freedom. Therefore, they approximate human development aims much more than mandates. Boosts, as non-fiscal and non-regulatory interventions intended to overcome people’s biases, improve their decision-making ability and empower them by providing meaningful heuristics, favor freedom the most. Thus, they are the closest-adhering to the human development project. These are not necessarily mutually exclusive policies. Depending on the issue, they can be complementary. As in the case of any policy, however, which policy or combination thereof is favored is a political decision and subject to deliberation in the public sphere. This is another aspect on which both the CA and BE seem to coincide.