Introduction

Much attention has been paid in recent decades to income distribution and the existing income gender gap in developed countries. This has not been the case, however, with respect to the distribution of wealth and patterns of asset accumulation by gender, for which considerably less analysis has been carried out. As the available literature usually illustrates, when it comes to wealth, data tends to be scarce and often aggregated at the household level, under the arguable assumption that members of a household have equal access to available wealth and enjoy similar levels of well-being.

This paper focuses on the analysis of wealth distribution in Spain from a gender perspective, using the microdata collected under the property tax law, a data set that has so far received little analytical treatment. This data set provides accurate statistics of the net wealth of the population with a tax base greater than 700,000 euro or assets with a value greater than 2 million euro, the wealthiest proportion of the Spanish population. The national tax law states, in its first paragraph: “an individual’s net worth is made up of the totality of assets and economic entitlements owned by the individual, free of any charges and encumbrances diminishing their value and deducting the value of total debts and liabilities of the individual.” Comprehensive data is thus collected in order to calculate individuals’ tax base, including a breakdown by gender of all the components that are considered in the calculation of total wealth. Despite the accuracy of this information, it is incomplete. On the one hand, as explained above, the data does not include information for individuals whose tax base is less than 700,000 euro. On the other hand, while information is provided for each autonomous region (Comunidad Autónoma, in Spanish), there is no distinction between urban and rural areas. But the fact that this data comes from a tax implemented on personal wealth makes it much more reliable than other options such as the Survey of Household Finances (Encuesta Financiera de las Familias). The problem with this survey is that it assigns 100% of the wealth to the person who answers the survey regardless of whether she/he is the actual owner of 100% of the household’s assets. Therefore, we believe that studying this subject from the wealth tax perspective is more reliable than the analysis of the gender wealth gap based on the Survey of Household Finances.

Over the past two decades, research on the distribution of wealth and rising inequality has been abundant, comprising the study of the evolution of asset accumulation by the different social classes in the largest economies of the world and shedding light on the increasing share of wealth going to individuals in the highest quantiles of the wealth distribution (Atkinson and Piketty, 2007; Piketty, 2014; Saez and Zucman, 2016). For Spain, Alvaredo and Saez (2009) study the available income and wealth tax return data and estimate the distribution of wealth between 1933 and 2005. The work by Artola, Estévez and Martinez-Toledano (2018) highlights the relevance of capital gains, housing, and offshore assets as centerpieces of long-term accumulation. They emphasize the importance of capital gains related to the real estate sector, which made up 45 percent of the real growth in national wealth between 1950-2010.

However, the existing literature on the distribution of wealth in Spain does not provide any information regarding the distribution of asset holdings according to gender and we find the literature is scarce internationally as well. As Deere and Doss explain, taking gender into account when looking at wealth inequality is relevant from a variety of perspectives and helps to better explain our societies. First, since it is highly probable for wealth to be distributed unequally between men and women, making it visible is relevant per se. Also, within the household, women do not necessarily share an equal part of men’s wealth. At the same time, some evidence exists that women and men use their wealth in different ways, and this can have broader social impacts. As laid out by Andreoni and Vesterlund (2001) or Mesch et al. (2011), the very concept of altruism is gendered, and it is a lot more likely for women to donate parts of their wealth than it is for men to do so. Owning assets can help prevent poverty by allowing for life choices that have deep social implications and influence the distribution of power. As the work of Panda and Agarwal (2005), Bhattacharyya, Bedi and Chhachhi (2011) and Kreager et al. (2013) seems to indicate, property and a stable income or more education lead to more freedom and can reduce the risk of being subject to domestic violence. Gender can also affect investment decisions and according to Neelakantan and Chag (2010), women might be more risk-averse, which could have profound implications for the economic and financial system. Nelson (2015) points in the opposite direction. In her review of 35 empirical works, she concludes that men and women tend to be much more similar in their responses to risk. Our contribution is not intended to close this debate, but as we will see in Section 5.2, our study shows that men and women in Spain have different profiles of accumulated assets. This can be attributed to the sociological and historical factors prevalent during the Francoist period, wherein women had limited involvement in the economy and faced significant obstacles in accumulating wealth. They were constrained by their unequal participation in social life and the restrictive norms imposed by the regime. In Section 3, we present a concise overview of this particular circumstance.

As we mentioned earlier, most wealth and gender studies conclude that available data is usually not sufficiently granular or is of poor quality. It is therefore important to develop better data bases in order to reach more robust conclusions (see Cantillon and Nolan, 2001:5; Deere and Doss, 2006, 2008:372; Warren, 2008; Deere, Alvarado and Twyman, 2012). According to the OECD, “No country in the world has such a perfect data source today. However, the countries that do have net wealth taxes generate useful data on wealth” (OCDE, 2018:33). Spain is one of the few countries that have such a database.

By studying wealth distribution only at household level, intra-household dynamics and gender inequality remain invisible. This is why some research has been carried out through surveys on smaller samples and field work in countries with different levels of development. Antonopoulos and Floro (2005) survey 134 couples in Thailand and conclude that asset holdings are different by gender and that women tend to possess fewer financial assets than men. A larger study was carried out by Doss et al. (2011, 2018), based on 9,172 surveys in Ecuador, Ghana, and Karnataka (India). They conclude, among other aspects, that the actual gender wealth gaps are currently underestimated and are only revealed when gender breakdowns are available. They also find that marriage laws play a crucial role in the resource gender gaps. But data gaps, poor quality or low coverage is not only a problem in lower income countries. In developed economies, despite increased data availability, intra-household distribution continues to be difficult to find.

Some recent studies conducted in developed countries use individual statistics. For example, Scheebaum et al. (2017) analyze the Household Finance and Consumption Survey in eight countries including Spain. To address the issue of unequal access to wealth and decision-making power within marriages, the researchers limited their analysis to households with a single adult. Due to the limitations of the Household Finance and Consumption Survey, this implies that in the case of Spain, their analysis had to exclude 87% of the population. Their conclusions are interesting and point in the same direction as our findings. They find a gender wealth gap exists at the upper end of the distribution but across much of the distribution there is little difference in wealth ownership between male and female single households.

Similarly, in the UK, Warren (2008) examines data from the Family Resources Survey and points out that the survey collects information on key assets at the household level, making it challenging to determine which adult member of the household owns those assets. Using a sub-sample of the Survey, Warren estimates a persistent pension-wealth gap. Women are shown to receive less pension benefits than men, since the latter have stronger links to the labor market and a higher probability to work full time and in higher paid jobs, which has a positive impact on wealth accumulation. In the same vein, Ravazzini and Chesters (2018) compare the gender wealth gap in Australia and Switzerland, using 2010 data from the Household, Income, and Labor Dynamics survey for Australia and 2012 data from the Swiss Household Panel. Both of these sources measure wealth at the household level, therefore the authors only take into account data regarding single households and conclude that the gender wealth gap is larger in Switzerland than it is in Australia due to the differences in permanent labor income (an indicator accounting labor-related income and years spent working), education and the type of wealth individuals in these two countries possess.

The analysis of the German Socio-Economic Panel (GSEP), which collects information on wealth for all adult household members at the individual level has received special attention. Sierminska et al. (2010) find a significant gender wealth gap for married partners in Germany, where the gap is driven by differences in terms of the individuals’ own income and labor market experience. Grabka et al. (2013) find that there are factors such as demography, income, labor market, inheritances, or financial decision making in the partnership that explain the wealth gap within partnerships. And Lersch et al. (2017) find a substantial motherhood wealth penalty where mothers’ personal wealth growth rates are lower compared to childless women and compared to fathers.

Frémeaux and Leturcq (2020) discover that wealth in France has become more individualized, attributed to the growing proportion of wealth held by singles and the individualization of wealth within couples. They also note that conventional measures of wealth inequality tend ot overestimate the share of wealth held by women. Their results indicate that the individualization of wealth is largely driven by changes in the demographic behavior of couples, such a later marriage and a higher risk of divorce.

Studies on gender economic inequality for Spain have generally focused on the labor market and income from paid work. Below, we summarize some of the most relevant research on the topic. Hernández (1996) reveals that gender wage gaps can be attributed to two factors. Firstly, there are wage gaps between men and women who work in the same occupation. Secondly, there is a growing trend of occupational segregation, with female labor being more concentrated in low-paying sectors. De la Rica, Dolado and Llorens (2008) study the gender wage gap in relation to educational levels and conclude that, in line with the conventional glass ceiling hypothesis, for highly educated workers the gap increases as we move towards the top of the wage distribution. However, for less-educated workers, the gender wage gap decreases among the highest wage earners in this group. Molina and Montuenga (2009) find evidence supporting the idea that a “motherhood wage penalty” exists in Spain. De la Rica, Dolado and Vegas (2010) find that women’s lower job mobility —due to the higher domestic work burden placed on women— has a stronger impact than occupational segregation on the wage gap. Lastly, Cebrián and Moreno (2015) conclude that women’s interruption of their professional careers, due family-related circumstances, accounts for over 50 percent of the wage gap.

We can conclude from the literature analyzed that wealth distribution is characterized by gender inequality, with women generally receiving a smaller share of wealth compared to men. This finding confirms the existence of gender-based disparities in the distribution of wealth and income in the cases examined. Due to data quality issues and variations in survey methodologies, there is some level of uncertainty regarding the real distribution of wealth. This is especially true of the data in the Survey of Household Finances, given that in the case of married couples, it allocates the wealth to the respondent. Spain is one of the few countries that has a wealth tax, which provides us the opportunity to conduct an analysis using real data. This, in turn, allows us to observe the main divergences in the accumulation of wealth between men and women.

The structure of the article is as follows: in Section 3, we review the legislative changes that have taken place in Spain in recent years and their impact on women’s rights to own and manage assets. These changes are highly relevant since they have conditioned women’s access to wealth and are crucial for understanding the economic obstacles that women have historically faced. In Section 4, we describe the available data, and in Section 5, we answer our research questions. Finally, we present our conclusions in Section 6.

I. Research Questions And Contributions To The Literature

The share of property tax in total national fiscal revenues has been dwindling worldwide due to the widespread implementation of neoliberal policies over recent decades designed to abolish wealth taxation and promote the liberalization of capital flows. This provided ample opportunities for wealthy individuals to engage in fiscal optimization across the globe. While fifteen years ago, ten of the twenty-six OECD countries levied taxes on wealth, only three of them still maintain these levees: Switzerland, Norway, and Spain. Spain also compiles detailed statistics on wealth distribution by gender, and, although long time series are not available, the national tax authorities hold granular microdata for the period comprised between 2012 and 2017. The evolution of wealth during this period is especially interesting since it captures two different phases of the economic cycle. The beginning of the period is marked by one of the worst years of the Spanish economic and banking crisis, with negative GDP growth between 2009 and 2013. Starting in 2014, GDP growth gradually returned to positive figures, and in the three following years, growth rates reached or came very close to 3 percent. However, it wasn’t until 2016 that GDP fully recovered to pre-crisis levels.

We try to answer several questions in our analysis:

Does a gender wealth gap exist in Spain and if so, is it increasing or decreasing? In 2012, the GDP fell by 3 percent compared to 2011, while over the following years, annual growth oscillated between 2.9 percent and 3.8 percent. The main stock market index, the IBEX 35, closed at 7,000 pbs in 2012 and rose to 10,000 by end-2017. Therefore, our interest lies in examining whether significant differences can be observed between the period of economic crisis and subsequent recovery.

Are there significant differences in the types of assets owned by women and men? As mentioned earlier, some studies suggest that women might be more risk averse. Consequently, we are interested in examining whether there is evidence of such differences in the data on property ownership in Spain.

Rising concentration among the wealthiest individuals has been a trend that several studies on wealth inequality have noted (Piketty, 2007; Alvaredo and Saez, 2009; Piketty, 2014; Saez and Zucman, 2016). This is also true for Spain, but we are interested in whether the same pattern can be observed for wealthy women and men alike.

Is there a gap between the income and the wealth of men and women? To answer this question, we study income distribution and the correlation between income and wealth by gender.

Finally, does the design of the property tax favor any gender in particular? The property tax law contains deductions and exemptions that we analyze in order to see whether both genders are equally impacted by them.

II. Legislative Changes: Steps Forward And Setbacks For Gender Equality

Although this article will mostly tackle the current state of the wealth distribution and its gender bias, we must bear in mind that Spanish society has experienced many sudden changes with respect to women’s ownership rights over relatively short periods of time. Thus, a woman in her mid-eighties will have lived through three very different regimes that conditioned her access to assets ownership and management.

For Spain, the 20th century was a period of intense and fluctuating changes. Prior to the proclamation of the Republic, in 1931, civil law was governed by the 1889 Civil Code, which was re-enacted during the Franco regime. This legal framework normalized and sanctioned a highly unequal position for women in society, including the explicit requirement for women to “obey their husbands” (Art. 57). With respect to owning and managing goods, it allowed women to be the owners of property, but not to incur debt or administer their assets, neither those acquired before nor those acquired during marriage (Art. 61 and Art. 1,384). The husband was to oversee the administration of the assets and act as the wife’s representative (Art. 60).

During the brief existence of the Republic (1931-1936), important formal advancements were made in the pursuit of gender equality. However, the time span was insufficient for these changes to become deeply rooted and widely accepted within society. The 1931 Constitution prohibited any type of discriminatory treatment based on gender in legislation (art.25) and established that both sexes were to be treated equally in terms of voting, and access to the labor market and education. It also introduced the right to divorce, which substantially improved women’s legal status.

Franco’s coup d’etat in 1939 initiated a long period of deterioration of women’s civil rights. The 1889 Civil Code was re-enacted and, again, wealth owned by women was placed under their husband’s administrative control along the lines already mentioned above and women were forbidden from acquiring any assets without their husbands’ consent. As for the assets they acquired prior to marriage, women were not allowed to sell, pawn, or place them as collateral. They were also not able to accept inheritance or ask for their corresponding part of assets during the settlement of an inheritance. Regarding access to the labor market, Title II – Article 1 prohibited women from working night shifts or carrying out any type of work in factories or workshops, relegating them to the sphere of paid or unpaid domestic work. In 1975, shortly before the return to democracy, a reform of the Civil code allowed women to buy and sell assets in her own name and contract liabilities. The assets acquired during marriage would continue to be administered by the husband.

It is not until the adoption of the 1978 Constitution that discrimination on the basis of sex, race, religion, opinion or any other personal or social circumstance was prohibited (under Article 14). In 1981, the Civil code was amended1 to recognize women’s equal treatment to men within the marriage , including in terms of the administration and use of marital property. In 1983, Spain ratified the 1981 United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women. However, it was not until 2007 that a comprehensive “Equality law” was passed, which introduced measures such as mandatory quotas for women in the public sector, on political parties’ electoral lists, and the governing boards of large companies. Despite these importantchanges in Spain over the past decades, which have contributed to women’sparticipation in all aspects of economic life, income and wealth gaps persist.

III. The Property Tax

Our study explores gender-based wealth inequality, an area where academic literature is not abundant, using data collected under the property tax law. This tax was reintroduced in 19772 and has been modified substantially since, and was suppressed between 2008 and 2011. Fiscal revenues related to property tax amounted to a mere 1,112 million euro in 2017 (less than 0.6 percent of total fiscal revenues that year). Individuals owning net assets valued below 700,000 euro are exempt from property tax therefore this population segment is not included in the statistics. This is a limitation of the data since it leaves out all individuals below the threshold, which make up the largest share of the population. As detailed in Section 1, the existing information is very granular and helps to shed some light on the research question put forward in Section 2. However, further research is needed to extend these findings to the broader population.

Around 200,000 individuals pay property tax in Spain annually3, whereas income tax is paid by around 20 million employees. This initial comparison provides a glimpse into the concentration of wealth in the country. The tax base of an individual and the size of their total wealth does not necessarily coincide since there are various deductions contemplated in the legislation. These include a) assets pertaining to the Spanish historical heritage; b) certain art objects and antiquities; c) economic claims on instruments related to pensions and insurance receivables; d) household related property; e) claims related to intellectual or industrial property rights; f) assets belonging to non-residents whose yields are exempt by other legislation4; g) entrepreneurial and professional assets if used in the development of economic, entrepreneurial or professional activity of the taxpayer; h) equity in certain firms, publicly listed or not, not including shares in Collective Investment Institutions; i) there is an exempt minimum of 700,000 euro; j) the first 300,000 euro of the value of the taxpayer’s primary residence. We add all the previous categories —included in our database— to the tax base so that we can obtain as complete a picture of total wealth as possible.

For confidentiality reasons, the data does not include the gender of the richest 1 percent of the population. This affects the analysis we are able to carry out of this group, as we only have access to gender breakdowns for average values pertaining to each of the categories listed above. As in other studies, we too use the FORBES list to analyze this fraction (Bricker et al., 2015). As it is widely recognized that men are predominantly represented among the world’s wealthiest individuals, we expect similar results in Spain. FORBES statistics illustrate that in 2012 and 2018, there were 0 women among the top 10 wealthiest people in the world. In 2012, there were 14 women with 12% of the top ten wealth, and in 2018, there were 11 women with 10% of the top 100 wealth. FORBES provides comprehensive data for 70 of the top 100 wealthiest individuals in Spain from 2015 to 2018. During that period, the top 19 richest women remained the same and there was a slight increase in the proportion of women’s wealth from from 14.8% to 15.2%. Contrary to the global top ten data, among the top ten wealthiest individuals in Spain, there were consistently 3 women throughout the entire period. Their wealth experienced a slight increase accounting for 10.4% of the total wealth of the richest individuals in 2015 and rising to 11.1% in 2018.

IV. Answers To Our Research Questions.

A. Is there a gender bias in wealth distribution?

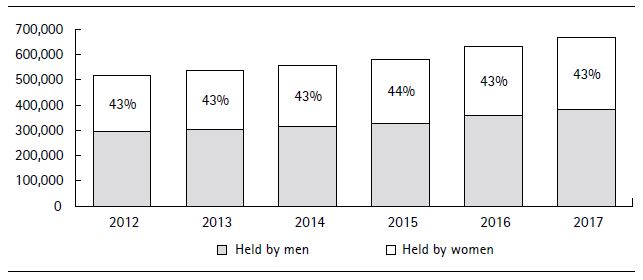

The gender breakdown of the Spanish population is fairly homogeneous: 50.98 percent of the population are women, while 49.02 percent are men. Figure 1 shows the evolution of wealth distribution according to the property tax database between 2012 and 2017. We can see that the proportion corresponding to each gender remains relatively stable and a considerable gap persists throughout the period, with men owning around 57 percent of wealth and 43 percent belonging to women. The fact that these shares have remained constant while total wealth increased means that men have reaped a larger amount of said increase. Such is the case that the gender wealth gapincreased in absolute terms from 74 billion euro in 2012 to 95 billion in 2017.Therefore, far from registering a decreasing trend, the wealth gap continuesto increase in absolute terms.

B. Are there significant differences between the types of assets held by men and women?

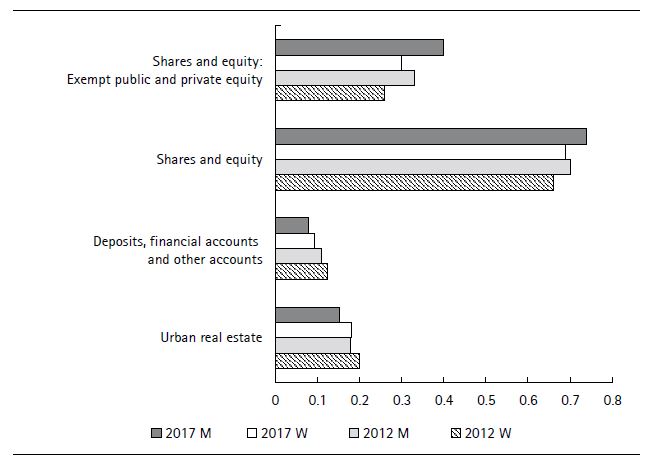

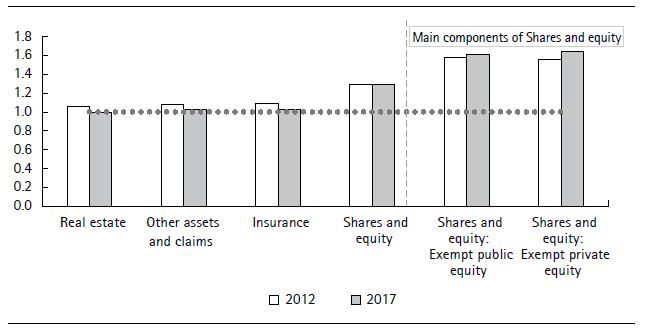

Figure 2 shows the share of men’s wealth compared to women’s by asset class. In the case of most asset classes, men hold only a slightly larger share, except for the assets we classify under Shares and Equity, where men hold a larger portion. This category constitutes 69 percent of women’s total wealth and 74 percent of men’s (see also Figure 4).

Within this category, the greatest differences are observed in holdings of exempt public and private equity, which are also among the main components of the category (44 percent for women and 54 percent for men).

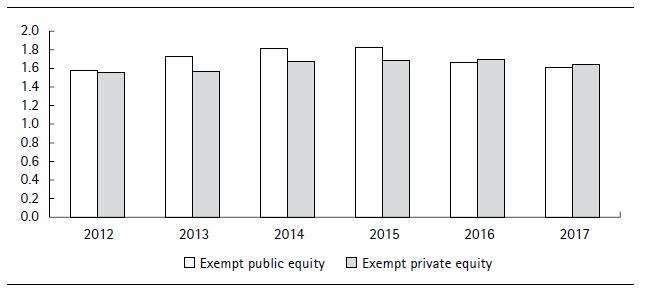

The significant difference in wealth attributed to equity holdings leads to several noteworthy conclusions. On the one hand, private equity is the largest asset class in the wealth structure, amounting to 33 percent of total wealth. And secondly, both categories have deep social and economic implication since they depict the ownership of the means of production. This substantial difference in the pattern of wealth accumulation shows that the gap between men and women’s wealth increases to 60 percent when considering only the property of the means of production. Therefore, we observe a property structurewhere men control the largest share of entrepreneurial wealth and theincome derived from these enterprises. A large part of these asset classes isexempt from property tax, which indicates that the design of this tax favorsmen. We revisit this issue in Section 5.5. Between 2012 and 2017, men’s holdings of wealth in the form of exempt privateequity was around 1.7 times greater than that of women. We observe asimilar pattern in the case of exempt public equity (Figure 3).

Source: Agencia Tributaria.

Figure 2. Asset breakdown of wealth componentsNote: Shares and equity contains listed shares in collective investment institutions, non-exempt public and private equity, and exempt public and private equity.

Figure 4 illustrates the distribution of wealth by gender and asset class, again highlighting the relevance of Shares and Equity (especially exempt equity): men hold 74 percent of their wealth in these types of instruments, while women’s holdings are 5 pp lower. We also find that urban real estate is the second source of wealth for both groups, a category that makes up for 18 percent and 15 percent of men and women’s wealth respectively. The third most relevant category, also included in Shares and equity, refers to listed shares in collective investment institutions of which women hold 12 percent and men 11 percent of their total wealth. Among the categories that represent less than 10 percent of each group’s wealth, housing has the highest share, making up 6 percent of women’s wealth and 4 percent of men’s. Arguably, the data show some similarity with the pattern suggested by Neelakantan and Chang (2010),according to whom women show higher risk aversion and concentrate theirwealth in assets whose value is less volatile than the assets men invest in.

C. Does rising wealth concentration follow the same pattern for men and women?

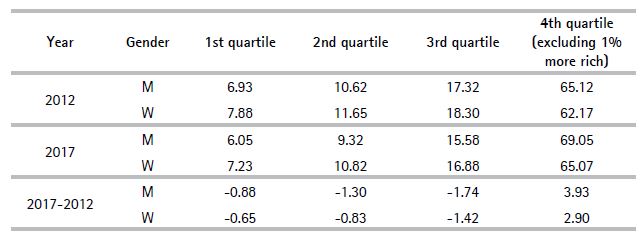

So far, we have found differences between the asset accumulation pattern for men and women, as well as a lower share of total wealth held by the latter. Table 1 illustrates both the distribution and the evolution of wealth by gender and quartiles. In line with the existing literature5, we observe an increase in wealth concentration among the wealthiest individuals from 2012 to 2017. This increase has been somewhat higher for men, who hold a larger share of total wealth. In all but the fourth quartile, the proportion of wealth held by both genders has declined. In the case of men, the first quartile has fallen by 0.88 pp, followed by the fall in the second quartile, which amounted to 1.3 pp,and finally a decrease of 1.74 pp in the third quartile. As a result, the highestquartile has experienced an increase of 3.93 pp. For women, the three first quartileshave decreased by 0.65 pp, 0.83 pp and 1.42 pp, respectively; implying arise of 2.9 pp in the fourth quartile. Thus, we conclude that both groups haveexperienced a concentration of wealth at the upper end of the distribution.However, this concentration has been more pronounced among men, indicatinga greater intensity of the wealth concentration process in their case.

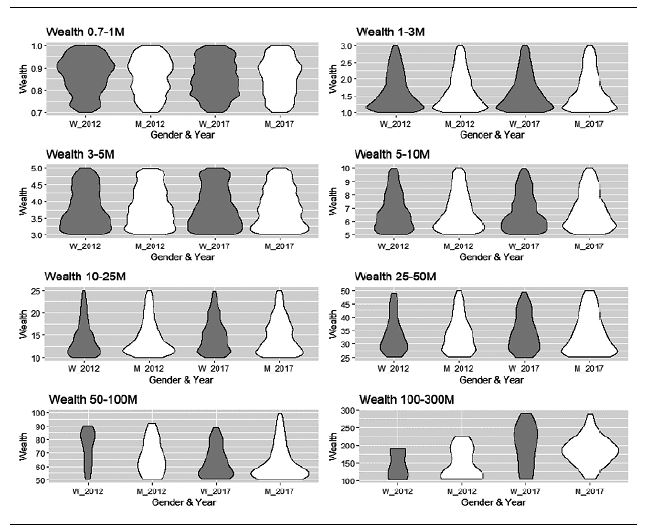

To conduct a more in-depth analysis of wealth distribution by gender, we depict density functions that represent different segments of wealth. Figure 5 illustrates different segments for each gender, allowing us to identify possible pattern changes between 2012 and 2017 and confirm the previously mentioned stylized facts. We observe a general increase in density for both genders above the segment ranging from 25 to 50 million euro. However, men consistently start from a higher wealth level compared to women in both in 2012 and 2017. In the lower wealth segments, there are no substantial changes throughout the period. Notably, there is a higher proportion of women in the first cut (from 0.7 to 1 million euro) in both years.

These findings provide evidence of the increasing number of individuals with substantial wealth, primarily driven by men, and the greater representation of women at the lower end of the distribution.

D. Is there a relationship between the gender wealth gap and the gender income gap?

This question is highly significant as it pertains to the previously identified gender bias in wealth distribution in Spain. A negative gender income bias would further contribute to the limitations faced by women in terms of accumulating assets.

As already analyzed, women hold fewer entrepreneurial assets than men, so that their ability to receive capital income is lower. This situation could be exacerbated by a relatively lower labor income for women. It must be noted that inheritance can also be a significant factor in wealth accumulation. Unfortunately, property tax statistics do not provide information on the source of the accumulated wealth and there is currently no available indicator that can serve as a proxy for inheritance. As a result, we are unable to include inheritance as an explanatory variable in gender-biased wealth inequality.

To shed light on the existing link between the gender income gap and the gender wealth gap, we first turn to the personal income tax statistics, as they record all kinds of earnings (income from labor, capital gains, earnings from properties not related to economic activity and earnings from economic activities and special regimes). Below, we draw on property tax data to study the relationship between wealth and the general tax base of the personal income tax.

Breaking down personal income tax statistics by gender is not straightforward, as some information might be biased depending on the type of return. In Spain, taxpayers can file individual or joint tax returns. The former reflects the income received by an individual in a given year. The latter attributes the total income of a marriage to the person that contributes the most to that income. Given the current design of this tax, only marriages that depend on one member’s income reap benefits (deductions, etc.) from filing this type of return.

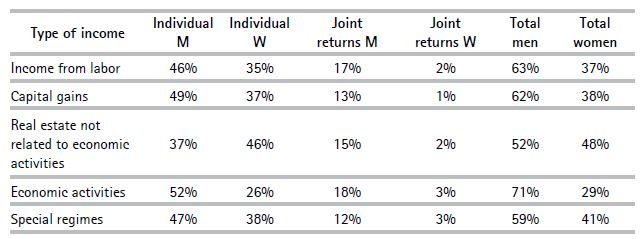

Table 2 presents the share of each type of earning6 by type of return and gender in 2017. For joint returns attributed to women (i.e., the women in these marriages earn more than their husbands), the shares of each earning are significantly lower, ranging from 1 percent to 3 percent. In the case of joint returns attributed to men (i.e., the men in these marriages earn more than their wives), the shares of each earning category span from 12 to 18 percent.

According to individual returns, men obtain a larger share of earnings in every category, except for that arising from property not related to economic activity7. We must emphasize the unequal distribution of the income arising from economic activity, as men concentrate twice the share of income compared to women. This is in line with the fact that men’s holdings of wealth in the form of equity have been around 1.7 times larger than those of women over the years, as analyzed in Section 4.2. The last two columns proxy the share of each earning category by gender, by adding together the earnings assigned to each gender from both types of filings. In conclusion, men have a significantly larger share of income in most relevant revenue categories (labor, real estate capital and economic activities), resulting in a significant gender imbalance in the income distribution.

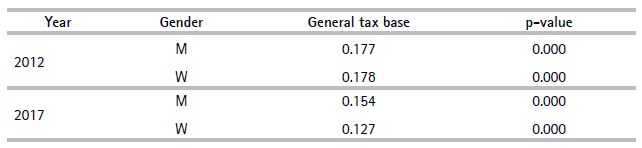

Having examined the gender-based income distribution, we addressed the correlation between wealth and income, with the latter proxied by income tax related data, which compiles all sources of taxable income. The general tax base accounts for the total taxable income of each individual and data is available in the property tax database.

The correlation coefficients (Table 3) between these variables were relatively similar in 2012 and decreased in 2017, particularly for women. This suggests two possible conclusions. First, the post-crisis growth period is marked by a decoupling of income and wealth growth. Second, this new growth pattern may disproportionately hinder women’s wealth accumulation. Further research is necessary to provide a more comprehensive understanding of these trends

E. Does the design of the property tax favor any gender in particular?

Articles 4 to 47 of the current legislation contain a series of tax exemptions and deductions. Among the most important exemptions, it is noteworthy that most private equity is excluded from the calculation of the property tax base. The availability of tax reliefs also depends on the Autonomous Region. For instance, the Autonomous Community of Madrid applies a 100 percent tax relief. This explains why 99 percent of the property tax reliefs in Spain is registered in the Autonomous Community of Madrid. Total tax reliefs in 2017 amounted to almost 996 million euro, which implies that if these benefits were not applied, total fiscal revenues would have exceeded 2,000 million euro. In the light of the significance of this fiscal benefit and the fact that most private equity is left out of the tax base, we study the existence of gender-biased fiscal benefits given each gender’s accumulation patterns and the design of the law. It is important to point out that although there is a 700,000 euro exemption for all taxpayers, Tax Agency data reflects the assets of the individuals before any type of exemption is made. The main exempt assets are the regular residence, with a maximum amount of 300,000 euro, assets that are part of the Spanish Historical Heritage, household goods, earnings from intellectual or industrial property, business and professional assets, certain business participations, etc.

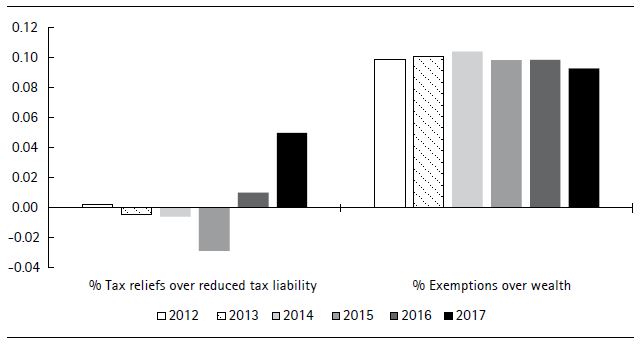

Figure 6 illustrates the percentage of tax reliefs on the total tax liability reduced by the deductions (“reduced tax liability”) and the relevance of the exemptions on total wealth from 2012 to 2017. The figure shows the difference between these magnitudes for men and women.

With respect to tax reliefs, both genders benefitted similarly throughout the studied period, although men were able to reduce their tax liability by 5 pp more than women in 2017. As regards the evolution of exemptions, the genderiscal benefit gap has widened over time. Approximately 40 to 45 percent of men’s wealth is exempt from being included in the tax base, whereas this percentage is around 10 pp lower for women. Thus, the current tax system is biased against women due to two reasons. Firstly, men tend to invest in equity, while women invest more in housing, resulting in an unequal distribution of wealth. Secondly, the design of the law favors the former.

V. Conclusions

Spain has experienced a significant transformation in its property tax legal framework, which has had an impact on women’s ability to accumulate wealth. When compared to the previous legal framework, there is no doubt that the gender differences have been reduced. Nevertheless, our analysis of the wealth data since 2012 indicates that the progress in reducing the gender wealth gap has stalled. Despite some relative stability, the gender wealth gap has increased in absolute terms over the period for which data is available.

The post-crisis growth accumulation pattern beginning in 2013 reveals that both genders have experienced an increase in the accumulation, particularly in the richest segments. Although this pattern was more pronounced for men, it can be observed in both genders.

We detect a clear accumulation pattern among men towards entrepreneurial assets, which has important repercussions on the social and economic structure, as this results in a prevalence of men owing the means of production. Nevertheless, the fact that men concentrate more of their wealth in economic activities renders them more exposed to changes in the business cycle. Women’s accumulation pattern denotes a preference for real estate, thus reflecting a more risk-averse profile. However, in this research we do not analyze the risk profiles of the genders. When examining concentration by wealth bracket, we find a clear trend of concentration in the higher strata for both genders, but more pronounced for men.

In general, not only do men own larger fortunes, but they also earn higher earnings from labor, capital, and economic activities. This reinforces gender inequality and their position of social and economic dominance. Finally, the very design of the property tax benefits the accumulation pattern of men since it rewards their accumulation profile thanks to the exemption of most of the assets they invest in.

Future research based on our findings could delve more deeply into the correlations between income and wealth, the composition of wealth by quartiles, or the factors that account for the different accumulation patterns.