Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Cuadernos de Administración

versión impresa ISSN 0120-3592

Cuad. Adm. v.20 n.33 Bogotá ene./jun. 2007

* El artículo es producto de una investigación relacionada con la tesis de grado. La tesis se llama, Los factores de entorno que fomenta y obstaculiza la creatividad organizativa: un caso de compañías colombianas seleccionadas. Este estudio se lleva a cabo como requisito parcial para obtener el doctorado en Filosofía de la Facultad de Administración de Empresas, Manchester Business School en la Universidad de Manchester, Reino Unido. La obra se realizó en el 2006. El artículo fue recibido el 18-03-2006 y aprobado el 01-06-2007.

** PhD in Organizational Psychology, University of Manchester, United Kingdom, 2006; MSc in Creativity and Change Leadership, State University of New York, Buffalo State, USA, 1996; BSc in Business Studies, State University of New York, Buffalo State, USA, 1988. Assistant Professor, International Center for Studies in Creativity, State University of New York, Buffalo State, USA. E-mail: cabrajf@buffalostate.edu

*** MSc in Ergonomics, Cranfield University, Bedfordshire, United Kingdom, 1965; BSc in Engineering ACGI at Imperial College, London, United Kingdom, 1963. Lecturer in Organizational Psychology, Manchester Business School, Manchester University, United Kingdom. E-mail: reg.talbot@mbs.ac.uk

**** PhD in Marketing, University of New Mexico, USA, 1974; MA in Psychology, University of Ohio, Ohio, USA, 1967; BA in Psychology, Kent State University, USA, 1965. Associate Professor, State University of New York, Buffalo State, USA. E-mail joniakaj@buffalostate.edu

ABSTRACT

The main objective of this paper is to develop conceptual models of cultural traits, Colombian characteristics, work behavior and processes, to determine the factors that resulted from a qualitative study on supporting attitudes and impeding attitudes regarding creativity in the workplace in certain Colombian companies. Data analysis of the interviewees’ statements produced 16 categories, such as ownership, trust building, support, influence management standards, envy / jealousy, and voluntary creativity. Some of these categories were incorporated into the conceptual models. In addition, several of the interviewees explicitly referred to Colombian culture promoting or smothering creativity in the workplace. The authors conclude by saying that it is rare to find structured descriptions that indicate a link between cultural characteristics and forms of thinking, feeling or behaving, which have an effect on issues of administrative importance. These potential explanations suggest that cultural climates influence behavior and, therefore, it is necessary to explore their possible origins.

Key words: Innovative behavior, industrial psychology, creating capabilities, resistance to change.

RESUMEN

El objetivo principal del artículo es desarrollar modelos conceptuales de determinantes culturales, características nacionales, comportamientos y procesos laborales para explicar los factores que emergieron de un estudio cualitativo, sobre los apoyos y obstáculos de la creatividad laboral en ciertas compañías colombianas. El análisis de datos de las narraciones de todas las personas entrevistadas produjo 16 categorías, como pertenencia, fortalecimiento de confianza, apoyo, normas del manejo de influencia, en-vidia/celos y creatividad deliberada. Algunas de estas categorías se incorporaron en los modelos conceptuales. Además, varios de los entrevistados se refirieron explícitamente a la cultura nacional como la promotora o sofocadora de la creatividad laboral. El artículo concluye que es raro encontrar descripciones estructuradas que provean nexos entre características culturales y las formas de pensar, sentir o comportarse, que tienen efectos en asuntos de importancia administrativa. Estas explicaciones potenciales sugieren que los ambientes culturales influyen en los comportamientos y, por lo tanto, se necesita explorar su posible origen.

Palabras clave: comportamiento innovador, psicología industrial, creación de capacidad, resistencia al cambio.

Introduction

This article posits the influence Colombian roots may have on behavior when associated with workplace creativity. An a priori qualitative study that explored factors that help and hinder workplace creativity from select Colombian companies served as the basis for this article (Cabra, 2006). Although this study was an inquiry of workplace climate, there were narratives that explicitly included a reference to national culture. In these instances, interviewees conjectured that national culture influenced creative climate in their organizations.

It is unusual to come across structured descriptions that connect characteristics of culture to emblematic ways of thinking, feeling, or behavior that have an effect on matters of managerial importance (Peng, Peterson and Shyi, 1991). Therefore, as means to structure and develop these narratives, three models were used to present potential explanations of the factors that emerged in this study, to promote a better understanding and appreciation of Colombian culture and to serve as a starting point for discussion and future studies. A brief description of the qualitative study is provided here before presenting these potential explanations.

1. Sample

1.1 Organizational Characteristics

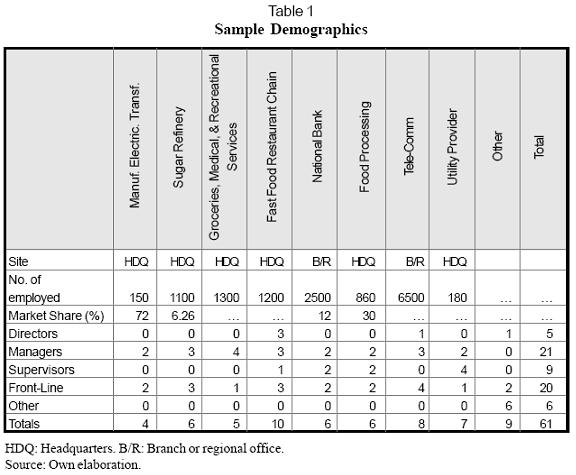

Two criteria were used in selecting the organizations. The companies recruited were national companies of 150 or more employees. Table 1 displays a breakdown of sample frequencies by level and by other demographic data. Jorgensen, Hafsi, and Kiggundu (1986) developed a classification schema to indicate organizations commonly found in developing countries. They maintained that a research study should include organizations from each category named in the schema, namely the governmental and State-owned organizations, the family-owned organizations, industrial concerns and multinational subsidiaries. The organizations involved in this study met the criteria as identified by Jorgensen et al. (1986). The national banking industry made up the multinational group with branches in the United States, Panama, and Cayman Islands. The telecommunications and utility provider made up the governmental and State owned group. The restaurant chain made up the family-owned company group; the chicken processing company, the grocery conglomerate and the electricity transformer manufacturer made up the industrial group. The sugar refinery fell outside this schema and represented the agricultural industry.

Rubin and Rubin (1995) suggested two ways to check for generalization among interviewee responses. One way is to pursue a saturation point whereby interviewees no longer provide narratives that are considered novel or do not differ from what was said by previous interviewees. In this study a saturation point was reached and documented (Cabra, 2006). Once the saturation point was determined, then the second way was to conduct dissimilarity sampling. To that end, dissident interviewees that were not employed by these organizations were included to provide viewpoints that differed from the mainstream, in order to enrich cultural perspectives, and to check for clarity, contradictions or generalizations of some interviewee’s comments (e.g., low salaries and no profit-sharing discourage creativity)(Arksey and Knight, 1999). These dissidents were business professors (n=5) the director of an incubator for the Coffee Belt of Colombia. Miles and Huberman (1994) sugand gested using these types of contacts to reduce researcher bias.

1.2 Participant Characteristics

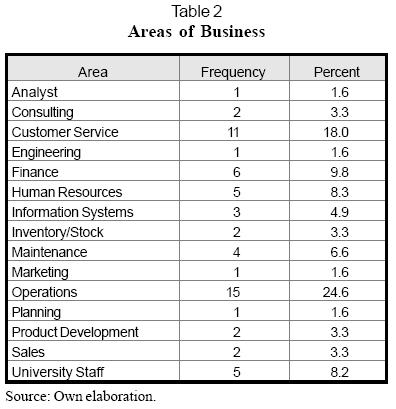

The participants were from several functional areas of business. In general, participants between the age of 30 and 49 accounted for 65.5% of the sample while 14.8% were 29 years or younger. The gender of the interviewees was 72% male and 28% female.

The educational profile shows that 1.6% had a master’s degree, 59% of participants had BA or equivalent degrees, 36.1% had high school diplomas and 3.3% had only middle school education. Approximately 93% of participants were Roman Catholic. Table 2 shows the frequencies for each division. Most participants worked in either customer services (18%) or operations (24.6%).

2. Methodology

A critical incident technique was used to identify behaviors and factors that contribute to the success or failure of individuals and organizations in specific situations (Andersson and Nilsson, 1964). A critical incident technique requires the researcher to ask interviewees for their own personal examples of creativity. Their examples did not have to be ones they directly experienced; they could include an event experienced by a coworker. The primary questions were taken and adapted from Burnside, Amabile and Gryskiewicz (1988) and were as follows:

Grounded theory methodology was used to analyze the data. Grounded theory is an interpretative approach and begins with researchers “immersing” themselves in transcripts and other documents to identify important themes (Abrahamson, 1983; Strauss and Corbin, 1990; Berg, 2001). Transcripts were read one sentence at a time, and key concepts or themes were coded so that codes could later be transformed into major categorical labels (Berg, 2001). Two other levels of analysis were applied. A panel consisting of three peers in the field of creativity questioned the researcher’s categorization of narratives. This was the second level. This process was conducted between June 2003 and July 2004. The third level consisted of 14 judges who sorted a random sample (20%) of the narratives into major categories to determine if they agreed with the researcher. A formula that combines decision theory and mathematics was then applied to the sorting results to determine inter-judge agreement (Rust and Cooil, 1994). As stated earlier, the focus of this article is to provide potential explanations of the factors; a more complete description of the methodology is included in an earlier article (Cabra, Talbot and Joniak, 2005).

3. Results

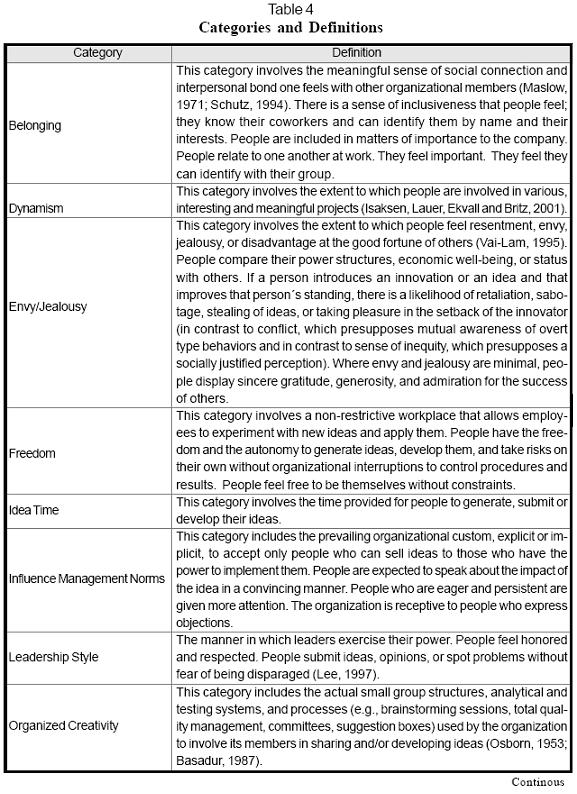

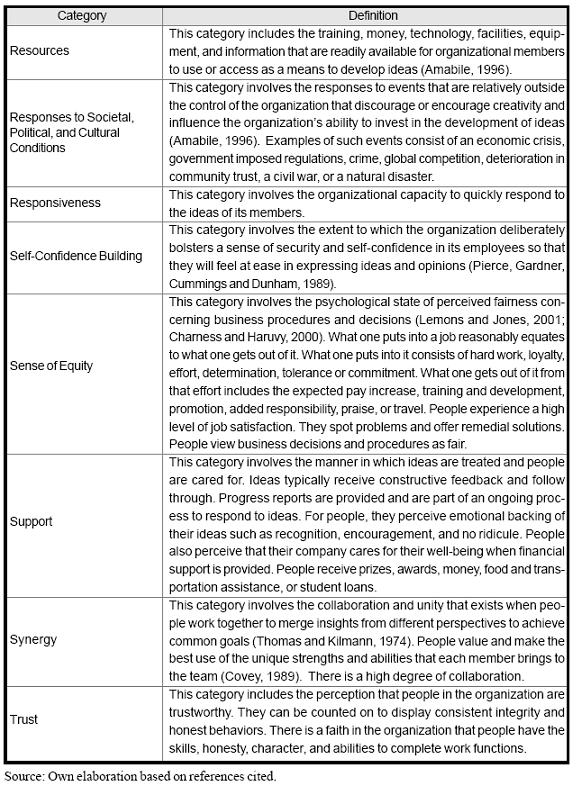

The grounded theory method identified 16 categories from 606,852 coded narratives and comprised approximately 75% of the text. The major categories are organized on the basis of four viewpoints: categories cited in published creative climate measures (Responsiveness, Leadership Style, Synergy, Trust, Freedom, Dynamism, Idea Time, Resources, Self-Confidence Building), categories that are cited in creative climate questionnaires but need enhancements of the accepted definition (Support), and categories that are distinct (Organized Creativity, Responses to Societal Political Cultural Conditions, Influence Management Norms, Envy/Jealousy, Belonging, and Sense of Equity).

The uncoded narratives either were not related to creative climate and did not contain a meaningful unit of information, or were related to creative climate but did not appear frequently enough to form a category: Betrayal (1), Peer Disrespect (1), Antagonistic behavior (1), Dislike of writing and elaborating ideas (1), Debate (1), Repetition of mistakes (1), Patience (1), Anarchist behavior (1), White lies (2), Too sensitive (2), Conflict (2), Integrity (3), Ethics (3), Self awareness (3), Tactfulness (3), Negative union mentality (3), Excuses (3), Bad temperament

(3) Poor social conscience (4), and Job Security (4). Table 3 shows a frequency count of comments made by the 55 respondents. Their narratives were organized by major categories, subcategories, and in some cases, subordinate categories that were developed from ideas and expressions raised in the narratives. In some cases, subordinate categories were linked under subcategories in order to delineate each category better and understand it more fully. Table 4 shows the names of the categories and their respective definitions as they emerged in the a priori qualitative study. These definitions were taken directly from the Cabra et al. (2005) article.

3.1 Discussion of Potential Explanations

Peterson and Smith (1997) presented a model of culture determinants, national characteristics, work attitudes and processes as shown in Figure 1. This model was modified to include outcomes influenced by managerial practices and attitudes and is shown in Figure 2. Figures 3, 4 and 5 then illustrates potential explanations of how the categories from the qualitative study could have emerged according to cultural values identified by Hofstede (2001) specifically depicting how national culture may influence factors facilitating or inhibiting a creative workplace.1

During the interviews, respondents mentioned that national culture influenced creative climate in their organizations. Therefore, potential explanations were provided using mostly a review of literature (Cabra, 2006). Roberts (1970) recommended understanding the causes of behaviors in organizations in a single culture as a basis for discussion and for future research initiatives.

Three cultural values identified by Hofstede (2001) were utilized in the model to help explain the factors and they are collectivism, power distance, and the avoidance of uncertainty. They illustrate the constant flow of cultural reinforcement among four constructs:

(1) the culture contributors construct, whichrepresents a person’s view of things such as historical, religious, political, or economic contexts; (2) the values construct, which represents the standards to which one subscribes; (3) the practices and attitudes construct, which represents the actions and practices that one exhibits at home, in public or in private; and, (4) the outcome construct, which represents the workplace outcomes (e.g., the categories revealed in this study) that are shaped by the culture. Each model as shown in the figures is followed by an explanation of the culture contributors, values, attitudes and practices, and outcome constructs. The goal is to relate cultural values relating to collectivism, power-distance, and the avoidance of uncertainty to categories revealed in the qualitative study.

3.2 Collectivism

One theme that emerged among the Colombian interviewees appeared to describe a value for collectivism, affiliation, and nurturance. Latin Americans of all socioeconomic levels consider collectivism as a basic Hispanic value group (Triandis, Marín, Lisansky and Betancourt, 1984). Collectivistic societies place a greater importance on group conformity in behavior as a form of survival. Moreover, people are more likely to support interdependent relationships, be more sensitive and conformist, and are readier to be influenced by others, and more willing to make sacrifices for the well-being of the group (Triandis et al. 1984). Figure 3 displays a theoretical alignment of cultural determinants, the creative environment categories, and Colombian collectivistic values.

3.2.1 Culture Contributors

To understand why this theme emerged in this study one has to examine the influences that agricultural and more traditional societies have on people’s way of thinking. Hofstede (2001) suggested that there is a relationship between agricultural societies and collectivistic values; people in agricultural societies live with extended families in which, “people from birth onwards are integrated into strong, cohesive in-groups, which throughout people’s lifetime continue to protect them in exchange for unquestioning loyalty” (p. 225). Colombian children are reared to depend on their extended families rather than be expected to “go it alone” at the earliest possible age (Ogliastri, 1998). Colombia made its transition from a rural society into an urban society very quickly - within 30 years of the beginning of the process in 1951 (Ogliastri and Dávila, 1987).

As society modernizes, there is an inclination to reject family complexity and to substitute it for a simpler nuclear one in which grandparents are sent to nursing homes, children leave home at an earlier age, and single parents lead private lives. Over time, modernisation generates more income and wealth.

As wealth increases, family members are subsequently in better positions to venture off, take risks, and express more independent types of behavior: questioning authority, personal achievement, pleasure, and the pursuit of personal goals instead of group goals. This suggests a relationship between a strong gross national product (GNP) of a country and individualism (Hofstede, 2001). Japan is the anomaly but that is attributed to its rapid transformation from an agricultural society after World War II.

3.2.2 Practices and Attitudes

People of collectivistic societies, such as in the case of Colombia, stress the needs of the group over personal goals and desires (Triandis et al. 1984). Although this is a good thing, when carried to an extreme it can produce slow consensus (Hampden-Turner and Trompenaars, 2000). In collectivistic socie-ties, conformity is valued as a way of harboring group strength and survival. The individual behaves in accordance with external expectations for protection, and desires to function as an important part of the social system. People are more likely to support interdependent relationships, be more sensitive and conformist; to be readier to be influenced by others, and more willing to make sacrifices for the well-being of the group (Triandis et al. 1984). People from these types of societies have a general tendency to avoid conflicts, be more appreciative and affirmative, and stress behaviors such as empathy and being sensitive to maintain harmony in relationships (Triandis et al. 1984).

3.2.3 Outcome Categories

Belonging, teamwork, emotional and instrumental support, and trust emerged as categories while autonomy, risk-taking, and conflict were infrequently mentioned. It is interesting to note that the infrequently mentioned concepts are important organizational aspects in individualistic societies that stress competition, independence, personal achievement, and individual initiative (Shkodriani, 1998).

A sense of belonging emerged as a category contributing to creativity. “Belonging” was indicated by the frequent use of the word pertenencia (the accepted equivalent in Spanish). Managers and front-line workers described the feeling of being part of family, the feeling of closeness, as a contributing factor to workplace creativity. They wanted to belong and felt that their companies played a critical part in integrating employees. Although involvement is mentioned as a contributing factor to workplace creativity, namely the extent to which the organization involves members in daily operations (Isaksen et al. 2000-2001), there exists in Colombia a unique, more personal aspect of belonging in that people desire to be connected and to feel part of something special—a bond. Respondents mentioned the enjoyment of meeting coworkers and learning about their interests and their families. “Sense of belonging” was mentioned frequently.

These findings are consistent with “familialism” research (Triandis et al. 1984). This is cultural value of immense importance to a Hispanic: it consists of fervent association with and attachment to his or her nuclear and extended families, reflected through strong feelings of loyalty, reciprocity, and solidarity among members. These findings are also consistent with the work of Fitch who found and explains the unique interpersonal relationships among Colombians in this way:

…to be truly a ‘person’ in the Colombian sense of the word—interpersonal bonds must be accorded primordial importance. Above and beyond individual hard work, luck, persistence, and the intervention of deities required to thrive in this environment [complex, uncertain, and difficult], human existence itself depends crucially on durable connections to other people. (1998, p. 18)

Participants from this study specifically mentioned desiring integration with their fellow coworkers and suggested the need for the organization to do more. Complaints ranged from not having a sense of family within the workplace to feelings of separation. That is why it does not come as a surprise to hear respondents highlight past events such as excursions, cookouts, dance parties, enjoyment of teamwork, and teambuilding exercises as contributors to creating a sense of belonging.

Emotional support emerged as an important subcategory under the collectivistic value. Support was indicative by dispositional behaviors. If a person was seen as dispuesto (willing), this entailed a real readiness or willingness to help develop an idea. Someone who was dispuesto, had shown support by providing encouragement and motivating remarks such as listo, empezemos (I am ready, let’s go) or adelante (carry on). In some cases, presenters of ideas succeeded in winning support because they had access to a padrino, a godfather willing to champion or sell an idea. In other cases, a boss or a support person accompanied participants while they explained their idea to a committee. This was another way of creating a bond.

Autonomy was mentioned infrequently where revolutionary creativity was concerned (creativity that can be viewed as unsettling). This result may also be attributed to the importance these corporate cultures placed on conformity and cooperation. Autonomy appears to run counter to the affiliation needs of Hispanics. This supports Hofstede (2001) who found that members of management from collectivistic societies scored autonomy as less important than security.

Triandis et al. (1984) may provide an explanation for the infrequent mention of autonomy within interpersonal relationships. They introduced the concept of simpatía to describe the social script of Hispanics whereby certain acquiescent and socially desirable forms of behavior are stressed to foster pleasant and smooth relationships in lieu of confrontational and other negatively related aspects of conflict resolution. In collectivistic societies personal goals are expected to be subjugated to the interest of the in-group (Schimmack, Radhakrishnan, Oishi, Dzokoto and Ahadi, 2002). Autonomy would appear to be an individualistic societal characteristic.

The data seem to support this subjugation. For example in one case, even suggestion boxes incorporated a group process where analysts and departments were assigned to work closely with individuals who submitted and got ideas tentatively approved for further examination. There was no mention of individuals going out on their own to experiment and pilot ideas; it appeared that people were never left to act alone. Rodríguez and Borrero stated: “...in Latin America…companies are more likely to be autocratic, rigid and be managed by personnel with little tolerance for mistakes. Creativity is more likely to be seen as a challenge to the status quo, as revolutionary and dangerous” (1996, p. 51).

It is interesting to note that risk-taking, debate, dynamism, achievement, challenge, competition, and commitment either did not emerge or were rarely mentioned. This is noteworthy because these values are more associated with individualist societies. As Hofstede stated, “Individualism stands for a society in which the ties between individuals are loose: Everyone is expected to look after him/herself and his/her immediate family only” (2001, p. 51). Individualistic cultures value individual achievement and believe that their members are exclusively responsible for decisions made and convictions formed (Hampden-Turner and Trompenaars, 2000).

But collectivistic cultures, such as Colom-bia’s, value cooperation, social concern and group harmony; and they believe that if individuals repeatedly look after the well-being of their fellow human beings, the quality of life will progress for all (Hampden-Turner and Trompenaars, 2000). This suggests that factors such as conflict, debate, risk-taking are more likely to disrupt group harmony. Consequently, autocratic leaders will apply rigid controls to any source of disruption. Notably, the Colombian sample instead mentioned concepts such as belonging, teamwork, and the subcategory support for bienestar (wellbeing). Trust also emerged as an important category. Participants indicated that building trust and self-confidence to share their ideas and opinions with the boss were important aspects to workplace creativity. They suggested that managers needed to do this so that people will not only be less afraid to express ideas but will also believe their bosses have instilled respect for them. The intricacies involved in navigating codes of proper conduct were also found in this study. One participant shared these thoughts:

The boss needs to build confidence in people and be their friends. The boss also needs to know how far the friendship should go. There are employees that try to confuse amiability with trust and abuse it. Bosses have to foster trust to a certain degree so that the operator knows what the limits are so that there will not be a problem when the employee wants to talk about problems not related to work. Bosses also have to be available to listen to these types of problem.

They seem to be asking for change that involved less formality at the top of the organization so that people feel comfortable telling others about a problem, whether it be personal, job-related, or about ideas.

When any cultural value is taken to an extreme, it produces a negative effect. When collectivism is extreme, people block others from escaping a perceived shared misery (Hampden-Turner and Trompenaars, 2000). The departure of a group member might be perceived as a threat to the group’s survival. As Puyana García (2000) stated, “In Colombia they can forgive your mistakes, but they can’t forgive your successes.” In this case, a person’s success may suggest the person may attempt to break away from the group to pursue entrepreneurial endeavours. This may explain why envy/jealousy emerged from the data. The 1.2 negative mentions per manager compared to 0.5 per front-line worker may suggest there is a higher degree of accomplishment and competition at the managerial level that may trigger envidia (Cabra, 2006)2 . Since collectivism values group harmony, group members that may be perceived as possessing an advantage may foster envy or jealousy. This notion of shared misery may also suggest why perceived fairness emerged as a category. Envy may be related to perceived fairness in that envy is a destructive social vice that hides behind such gracious names as equality, fairness, and even social justice (Novak, 1993).

In short, collectivistic behavior stemming from an agricultural societal antecedent and reinforced by current social, political and economic conditions has moderating effects on aspects that influence creativity in the workplace. To maintain group harmony, people are diplomatic, supportive, trusting, sensitive, conformist, conflict.-avoiding and obedient; and they strive to belong. In turn, these forms of behavior may become counterproductive when idea-groups consider radical or crazy ideas.

3.3 Power Distance Value

Hofstede (2001) identified another cultural value called power-distance. It involves the degree of equality or inequality that is expected and accepted by people, especially by those less powerful. Where inequality or high power distance exists, society places more weight on things such as wealth, prestige, and power. When organizations are considered, disparity of power is typical and recognized in subordinate-boss relationships. Colombia is a high power-distance culture where front-line workers are more likely to behave accordingly to maintain the status quo because risk-taking behavior, in affect, may threaten the more powerful individual striving to maintain or increase his or her power distance (Hofstede, 2001). Figure 4 displays a hypothesized alignment of cultural determinants, the creative environment categories, and Colombian power-distance values.

3.3.1 Culture Contributors

Colombian was ranked high on the power-distance scale (Hofstede, 2001). An explanation may be traced to another Colombian historical root. Phillip II and his successors handed down to the Spanish-speaking world a tradition of politics accustomed to absolute monarchial governance, centralism, efficiency, and authoritarianism (Véliz, 1994). The Jesuits also played an important role in the cultural development of Latin American in that they imposed their spiritual methods on the individual and subjugated his or her rights to the idea of the whole (Véliz, 1994). Latin American societies were accorded status when they garnered an insatiable resistance to change, was well-ordered and devout (Véliz, 1994). In effect, as Rodríguez and Escobar stated:

Empowerment is a utopia in Latin America. Instead, companies are more likely to be autocratic, rigid and be managed by personnel with little tolerance for mistakes. Creativity is more likely to be seen as a challenge to the status quo, as revolutionary and dangerous. (1996, p. 51)

Bentley (2002) identified the “acting out” of four deeply held values and assumptions in Latin America: “Respect for our leaders is required for effective teamwork”; “I and only I should control all that goes on in this office”; “I can fire whom I wish, when I wish, for whatever reason”; and, “mistakes in public will not be tolerated.” (p. 31) Trompenaars (1994) provided insight into how these values and assumptions continue to be reinforced through a child’s upbringing insofar as the father is paternalistic and decides how things should be done. He likens the organizations in Latin America to be very much like a family in that it is paternalistic and hierarchical.

3.3.2 Practices and Attitudes

Authority is used deliberately and managers depend on prescribed policies. Subordinates expect to be instructed. According to Hofstede (2001), all societies have a “pecking order”. However, societies vary according to the value it places on this “pecking order”. For example, although the researcher gave instructions that front-line employees should be interviewed, some Colombian contacts did not distribute the material to them. The contacts were surprised by the researcher’s insistence on interviewing front-line employees. From a cultural perspective, there may be something to this, perhaps a class system. Where equality or low power-distance exists, society places more weight on fairness and plays down the differences between a citizen’s power and wealth (Hofstede, 2001). When organizations are considered, centralization of power is typical and recognized in subordi-nate-boss relationships (Hofstede, 2001). Consultation is used deliberately. Managers depend on the input of their subordinates. Subordinates expect to be conferred with.

Trust emerged as a category, but change can be a formidable challenge because of the dilemma it poses between confianza (trustworthiness) and authority (Autocratic Leadership). Confianza signifies trust and closeness but as Fitch (1998) signaled, its definition is to a certain extent true within a Colombian context in that it exists in de-grees and operates among a combination of interpersonal behavior categories such as trust, reliance, confidence, and unconditional social support (From Fitch, 1998):

…to invoke ‘respect’ as what may be lost or violated in a bad friendship locates confianza in a symbolic web of interpersonal forces centered around a code of ‘proper conduct’ in which the risk of acting too informally (being confiazudo) [too chummy] is ever present. (p. 28)

As a participant in this study described, “People here think I am cold and distance maybe a bit conceited. They do not realize that I want to keep my distance to prevent people from taking advantage of me in the case of friendships. I also think that by being distant, I can get things done and I am more effective.” A more distrusting supervisor used the phrase, “No dar papaya y aprovechar cualquier papayazo (Don’t let yourself be taken advantage of, and take advantage of any opportunity yourself),” to explain the dilemma. Fitch (1998) said that trust, in the Colombian sense of the word, conveys the threat of misuse and exploitation. Authority carries the disparate threat of being seen as distant and subversive. This notion of trust goes beyond the emotional safety definition described in creative environment literature. Presumably, one cannot just provide trust without the prerequisite passage of time.

3.3.3 Outcome Categories

Autocratic leadership emerged as a category. In general, respondents mentioned autocratic behaviour as an impediment to workplace creativity. Autocratic leadership was mentioned 1.7 times per manager and front-line worker as negative comments. Workers did identify positive aspects of autocratic behavior,

0.1 times per worker. Positive comments suggested that workers do accept directive type of behaviors as helpful to workplace creativity as long as the behavioural style was respectful and benevolent. When the leadership style was not respectful and benevolent, people felt a sense of unfairness.

In a review of sociological studies of Colombian organizations, Arango Gaviria (2000) determined that applications of Japa-nese-inspired socio-technological processes have been selective and combined with scientific management practices (Taylorism). Mayor (1992) and Weiss (1994) stated that it is common to find organizations in Colombia that employ autocratic management styles characterized by tight control. Implicitly, this may also explain why openness may be difficult for managers when listening to employee suggestions and ideas.

Conflict emerged as an infrequently mentioned category. Debate was mentioned once. Fitch (1998) explained that the loss of respect translates into a perception of having lost advantage and the power to influence others. It translates into a loss of control because one is no longer in the hierarchical position to which one had laid claim (Fitch, 1998). Consequently, relationships become murkier and more challenging to manage. According to Fitch (1998), many Colombian managers conclude that the best way to preserve respect is to manage subordinates coercively and autocratically. Therefore, a manager must give directives continuously, or else risk letting subordinates get the upper hand. The manager must always be on a lookout for encroachments over the area of respect for one’s superior, or suggestions of false relational trust (Fitch, 1998; Weiss, 1994). Perhaps conflict and debate may be perceived by a manager as an encroachment, which could lead to retribution upon the individuals who produced the perceived offense. Understanding this reality may influence people to avoid taking risks and instead to maintain a routine or a low dynamic workplace environment.

In short, an absolute monarchy, reinforced by Jesuit philosophies and paternalistic forms of behavior may have influenced Colombia’s value for power-distance. Over time, these influences produced autocratic leaders who misapplied scientific management methods e.g., an approach to management that searched for the best way to complete a task (Higgins, 1994). Bureaucracy was used as a tool to reinforce control. Ideas were met with caution and a closed mind. In effect, risk-taking, debate, and the avoidance of conflict prevailed in the workplace environment. Instead, the workplace was enabled by routine.

3.4 The Avoidance of Uncertainty

Another pattern that emerged among the Colombian respondents was the value they placed on executing possible measures to reduce uncertainty, so that ideas when screened are implemented correctly and efficiently from the start. Hofstede stated:

Extreme uncertainty creates intolerable anxiety, and human society has developed ways to cope with the inherent uncertainty of living on the brink of an uncertain future. These ways belong to the domains of technology, law and religion. I use these terms in their broad senses: Technology includes all human artifacts; law, all formal and informal rules that guide behavior… (2001, p. 146)

According to Hofstede (2001), the avoidance of uncertainty measures the degree to which people feel threatened by uncertainty and ambiguity and in effect feel that it must be combated. If we are to understand why this pattern emerged so strongly, we must examine the implications of Colombia’s historical roots amplified by current social, political, and economic conditions. Figure 5 displays a hypothesized alignment of cultural determinants, the creative environment categories, and Colombian values for the avoidance of uncertainty.

3.4.1 Culture Contributors

A predominant social script of Latin Americans is the avoidance of uncertainty, which is a cultural trait that was in inherited from Metropolitan Spain, which had in turn been influenced by the Romans (Recht and Wilderom, 1998). The Romans used to govern their far-reaching territories by creating a strict system of control and unified codes of laws. Over time, these control systems in turn created a penchant for predictability among the people with no tolerance for uncertainty (Hofstede, 2001). The Spaniards in certain respects drastically repressed the entrepreneurial spirit of the people and in its place imposed aristocratic and bureaucratic values that eliminated personal responsibility for action and reduced the creation of new innovations and new wealth (Sudarsky, 1992). According to Véliz (1994), Phillip II and his heirs bestowed to Latin America one of the most bureaucratic, legalistic, and well-documented political systems in the modern world as their way of life.

Ogliastri (1998) established that Colombia has a most uncertain cultural environment, fueled by free trade—recently transitioned from a domestic protectionist economy—a new constitution ratified in 1991, a recent eradication of a false drug economy, a decentralization of political power, a war on drugs, an on-going war with left-wing guerillas, violent crime, kidnapping, and the mass displacement of people fleeing violence.3

3.4.2 Practices and Attitudes

People in societies that seek to avoid uncertainty, such as Colombia, need rules and assurances as means to reduce or cope with uncertainty. When ideas are presented, measures are taken to screen, select, study, test and retest them to ensure that the idea, when employed, is given every chance of success. Therefore, people tend to be more skeptical, and critical of radical ideas (Hofstede, 2001). This may also stem from the lack of local resources. In this society, waste is not an option and efficiency is essential, however. On the other hand, when carried to an extreme it can produce slow-moving consensus bureaucracy, where rules are applied to the letter, and never used as guidance.

Paradoxically, the uncertainty that may stem from a chaotic environment will affect forms of behavior such as improvisation, flexibility, resourcefulness, creativity as means to address or react to a uncertain situation. People have a seasoned way about them in dealing with emergencies (Ogliastri, 1998).

3.4.3 Outcome Categories

In the light of the forms of behavior mentioned, one can understand why Bureaucracy, Resources, and responses to Societal, Political, Cultural Conditions emerged as categories effecting workplace creativity, while Risk-taking (9), conflict (8), and debate (1) were factors infrequently mentioned in the interview data. This may also explain comments suggesting that organizations lacked dynamism and instead were dominated by routine. People from societies with high rate of uncertainty, such as that of Colombia, stress the need to avoid conflict and competition (Hofstede, 2001).

Latin America’s penchant for stability, control, and predictability may explain why the Colombian sample provided few innovative examples and had a preference for adaptive creativity. Perhaps innovative creativity is perceived as a threat to certainty, to limited resources, and to a leader’s authority. Véliz posited that, “This quiet, almost inarticulate disinclination to change anything has proven unusually persistent and ought not to be ignored when considering the culture and society of the Latin American beneficiaries of the [Spanish] Baroque inheritance.” (1994, p. 86)

Respondents identified bureaucracy as stifling to workplace creativity as indicated by the negative comments per manager and front-line worker, 2.6 and 1.0. However, companies that responded positively to uncertainty also very frequently mentioned research, analysis, and the testing of ideas as contributions to creativity because a well substantiated idea had a better chance of overcoming bureaucracy. This suggests two things: first, people cannot afford to make mistakes, because national and organizational resources are limited. Naturally, people are likely to be careful about how they utilize their resources. Additionally, it appeared that those who were skilled at managing the influence of others were more likely to receive acceptance of their ideas.

Managers and workers frequently cited training as an important contributory resource for workplace creativity. Although the respondents listed this resource as a positive contributor in their experiences, they also mentioned a strong appetite for more, and cited these resources as a badly-needed commodity to help them acquire expertise and knowledge, as contributory factors to workplace creativity and productivity. Improvisation was also cited as a contributory factor in support of creativity. Yet improvisation is influenced by a lack of resources as mentioned by the respondents. Negative comments were attributed to the lack of money to invest in modernization, equipment and facilities, let alone pilot schemes for new ideas.

Re-testing and analyzing ideas may be a way to combat waste—it is a controlling system. Second, the avoidance of uncertainty has been associated with two main dimensions of organizational structure, namely, the concentration of authority and structuring of activities (Hofstede, 2001). Thus, re-test-ing and analysis is also a tactical approach to reducing uncertainty while the concen-tration of authority is an approach to help control deviation. The Colombian culture ranked high on a scale involving the avoidance of uncertainty, compared to developed countries such as United States and Britain (Hofstede, 2001).

Support, however, as the findings showed, did not always mean that ideas would receive immediate attention. In many cases ideas had to be researched, tested, analyzed, and made defensible to be considered for a development stage. This may suggest that in light of limited resources and uncertain external conditions that exist in Colombia, extra measures have to be taken to assure that ideas are properly implemented the first time round. This may suggest why selling ideas and managing influence was considered a contributor to garnering support for ideas. As one participant in this study stated, a person can have any idea accepted if it is justified and shown to produce immediate returns. The flipside of a demanding organizational expectation of its employee to substantiate ideas is that it also makes them less confident from constant exposure to critical feedback. This may in turn suggest why confidence-building emerged as a theme.

It is no surprise that unpredictable political and economic conditions emerged as a category in this study. Colombia today has 11.9% unemployment (Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística, May 2007); there are constant changes to government policies, and there is violence and social and economic crisis. Poor economic conditions in Colombia were often cited as having and not having a contributing influence on workplace creativity. Collectively, SPCC was mentioned 2.0 times per manager and front-line worker. This may suggest that economic conditions have become sustained and serious enough to affect all socioeconomic levels. When members of an organization reacted positively to crises arising from poor economic conditions, they responded by applying radical ideas in some cases (e.g., applying just-in-time or outsourcing for the first time as an extreme departure from the old way of operating) and improvisation in others (e.g., using an above-ground electrical transformer—de-signed for above ground purposes only— for underground purposes). When economic conditions were bad, organizations were precluded from upgrading equipment and making other investments. Respondents were quick to blame politics and policies as a compounding factor to Colombia’s economic woes.

In collectivistic societies, conformity is valued as a way of harboring group strength and survival. The individual behaves in accordance with external expectations for protection and desires to function as an important part of the social system. This may further explain why financial support, belonging, and support for the well-being of others emerged from the data. The narratives showed that when rewards are introduced, especially rewards that alleviate physiological and social needs, front-line workers would view them as facilitators of creativity. This suggests that in a developing country like Colombia, there is a preoccupation at the front-line level to make enough money to pay for necessities such as gas, electricity, food and water—In Colombia, the minimum wage is COP408,000 (USD182) a month (Universia, 2006). This necessarily suffocates any form of workplace creativity.

Front-line workers also reported that a dearth of instrumental support did not contribute to creativity. As suggested by an interviewee:

There should be some form of compensation. I would say more money. Why money? If I am told this is my job and I am not provided incentives, I am not going to submit ideas. Look, for sales (department) they provide them incentives with 80,000 pesos (28 USD) per quarter. That is a good practice. They tell themselves, ‘With this money I can pay the gas, water, and more.’ It attracts their attention.

Thirty respondents identified the well-being of employees as important and named items such as appliances, food vouchers, home loans, car, and school loans, transportation vouchers, medical insurance, salary increases, and profit sharing. The mention of physiological security may suggest something else: extrinsic motivation, among the respondents, contributes to creativity and precedes intrinsic motivation if basic motivational needs, as suggested by Aldefer (1972), are not met. The motivational needs as described by Alderfer (1972) are Existence, Relatedness, and Growth. The data in this study suggest that people focusing on satisfying Existence-needs (such as in a society which places high values on the avoidance of uncertainty), and to some extent Relatedness- needs (such as in a Collectivistic society), do not have time for growth needs or are creative mainly in the service of Existence-needs as seen above by the number of mentions.

Although Organized Creativity was mentioned as an effect of collectivistic values, it also provides a formalized structure to reduce uncertainty. Structured small group meetings such as committees and brainstorming sessions were commonly cited as being helpful to workplace creativity. Organized Creativity had elements of shared responsibilities. For example, even suggestion boxes incorporated a group process whereby analysts and departments were assigned to work closely with the person interested in submitting an idea. There was no mention of individuals going out on their own to experiment and pilot ideas. Nobody was ever allowed to act alone. Hofstede stated that, “…in a high uncertainty avoidance Index, there is an ideological preference for group decisions, consultative management, against competition among employees.” (2001, p. 160)

Basadur, Pringle and Kirkland (2002) investigated the impact of creative problem solving training on South American managers, namely Peruvian and Chilean. They used a translated version of an 8-item attitude scale to measure “preference for premature convergence (a preference not conducive to creativity because it suggests being quick to judge)” and a 6-item scale to measure ‘preference for active divergence such as to strive for many and crazy ideas. Creative problem solving (CPS) training therefore, as one should expect, should have influenced this group to score premature convergence as counterproductive to creativity when completing the measure. It did not happen that way. Basadur et al. (2002) believed this may be attributed to the Spanish-speaking culture in that its values counter competition and deviance. This may indicate the interplay of collectivistic values to avoid crazy, frivolous, and unexpected behavior such as childish conduct or play. Basadur et al. (2002) posited that, “It also may be that Spanish-speak-ing South American managers, who place emphasis on consensus and prefer to avoid conflict and uncertainty, would try to limit their ideas to those they believe would be acceptable to the group.” (2002, p. 405)

According to Velásquez Lopera (personal communication, 2002), a director of a Colombian idea incubator for the Coffee Belt, creativity in Colombia is reactive and based on a response to crisis and urgency. This may explain why there is little time dedicated or available to play with ideas and experiment. It may also explain why an idea, especially an innovative one, is met with threatening criticism. Ideas that survive initial scrutiny are then required to journey through yet another stage of bureaucratic scrutiny or be ensnared in one level of red tape after another.

In short, the avoidance of uncertainty stemming from unstable social, economic, and political conditions, politically violent historical roots, and limited resources have moderating effects on organizational aspects that influence creativity in the workplace. In effect, bureaucracy limited resources and promoted conformist and cautious behavior that moderated all forms of risk-taking, debate, autonomy, and dynamism.

Conclusions

This article provided potential explanations about the influence Colombian historical and social roots can have on behavior when associated with workplace creativity. Models were constructed to present these potential explanations. Future studies should examine the categories that emerged in this study to other regions of Colombia to see how far they can be generalized. One approach might be to conduct several focus groups with Colombian academics to confirm, deny or explain the findings. Perhaps the potential explanations in this study may serve as a starting point. Another outlook may be to expand the qualitative study to other regions of Colombia. Another study might include a comprehensive review of literature in Colombian journals and books to examine support for these categories. Nevertheless, much more work needs to be done if we are to understand the complexities of what helps and hinders creativity in Colombian workplaces more fully.

For example, cultural gaps between a developing country and developed country have a propensity to close on macro-level issues when organizational technologies such as design thinking are shared throughout the world, but the specific differences such as organizational behavior widen the gaps at the micro-level (Child, 1981). Colombian managers cannot simply assume the social processes can easily be transferred to their organization from another country and vice versa. They may need to be adjusted or modified. Universal constructs may cause a manager to overlook key aspects of events he or she desires to understand relative to a target culture (Davidson, Jaccard, Triandis, Morales and Díaz-Guerrero, 1976).

When a systemic view of creativity is considered, the complexity of these transfers are intensified. This article discussed only one component of a systemic view of creativity namely, the environmental component, which relates to the climate, culture and physical attributes found in an organization that impacts the person and the process. The other components of a systemic view are the personal characteristics which refer to the personal qualities that prompt the individual to be creative, such as, certain skills, personality traits, subject background, prob-lem-solving inclination and motivation; and the process which refers to the stages of thinking an individual or team goes through to solve a problem creatively (Puccio, Murdock and Mance, 2006).

The interaction of these three components, when it functions well (personnel have the right skills, abilities and motivation to participate in an effective creative process buoyed up by their work environment) contributes to a creative output (Puccio, Murdock and Mance, 2006). “Creative output” refers to any outcome of the interaction of the person, process and environment, such as a new theory, invention, idea, service, or a solution to a problem (e.g., internal problem, customer problem, etc). In general, creativity leads to change when products are adopted with minimal resistance by individuals, teams, organizations, and society. The systems view points to some of the reasons why bringing about creativity and innovation in organizations can be difficult, since the system can break down at any point (Puccio, Murdock and Mance, 2006).

As stated earlier, the categories that were explained in this study are only one aspect of the systemic view. Therefore Colombian managers must examine their organization from an “ecological” standpoint to diagnose what impedes the organization’s capacity to innovate. Colombian managers should also examine their leadership approaches to determine to what extent their habits get in the way of workplace creativity in their organizations. Ekvall (1996) determined that 67% of the statistical variance that is accounted for in an organizational environment/climate is attributed to leadership behavior. Therefore, for example, if people feel joy and meaningfulness in their job, and they are willing to invest energy in their work, one can say there is a 67% chance that it is being attributed to the leader’s behavior. However, if people feel alienated and are indifferent to their work; they are apathetic and disinterested in their jobs and the organization; one can say there is a 67% chance that it’s attributed to leadership behavior.

Future studies might examine what real statistical variance is caused by the leader’s influence in Colombian organizations. Another study comprising ethnography can examine how cultural values block or hinder personal creativity. Researchers can embed themselves inside willing organizations for several weeks. Their findings can then be shared with a panel of Colombian experts from the fields of organizational psychology and historical anthropology for interpretation. Another qualitative study, that applies the same methodology in this study, might be conducted with population groups from other regions of Colombia, in order to identify new helps and hindrances to workplace creativity. Another study might examine the organizational aspects that influence workplace creativity in Colombian companies identified as the most innovative and compare these findings to companies identified as the least innovative. This study poses one of the first attempts to gain awareness of the uniqueness of the Colombian situation as it pertains to the field of workplace creativity and maintains that a more deliberate and scientific effort are needed to establish the implications for Colombian management.

Footnotes

1. The authors positioned this paper as potential explanations of the categories. These explanations were not meant to be generalizations and instead, were meant to prompt reflection and discussion through an inventive mean of organizing and presenting data of plausible cultural influences. The potential explanations as proffered in this article were not grounded within the scientific process.

2. Due to limitations of space, we do not include the complete results with all the mentions per person by organizational level.

3. A recent BusinessWeek cover story reported, however, Colombia’s journey from crime capital to investment hot spot suggesting an increase in confidence (Farzad, May 28, 2007).

List of References

1. Abrahamson, M. (1983). Social research methods. Prentice Hall: New Jersey. [ Links ]

2. Alderfer, C.P. (1972). Human needs in organizational settings. The Free Press: New York. [ Links ]

3. Amabile, T.M. (1996). Creativity in context. Boulder, CO: Westview Press Inc. [ Links ]

4. Gryskiewicz, S.S. (1988). Creative humanresources in the R&D laboratory: How environment and personality affect innovation. In R.L. Kuhn (Ed.), Handbook for creative innovative managers (pp. 501-524). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

5. Andersson, B. and Nilsson, S. (1964). Studies of the reliability and validity of the critical incident technique. Journal of Applied Psychology, 48 (6), 398-403. [ Links ]

6. Arango Gaviria, L.G. (2000). Innovación y cultura de las organizaciones en la región Andina. In F. Urrea Giraldo, L. G. Arango Gaviria, C. Dávila L. de Guevara, C.A. Mejía Sanabria, J. ParadaCorrales, and C.E. Bernal Poveda (Eds.). Innovación y cultura de las organizaciones en tres regiones de Colombia (pp. 219-281). Bogotá: Tercer Mundo-Colciencias. [ Links ]

7. Arksey, H., and Knight, P. (1999). Interviewing for social scientists. London: Sage. [ Links ]

8. Basadur, M. (1987). Needed research in creativity for business and industrial applications. In S.G. Isaksen (Ed.), Frontiers of creativity research: Beyond the basics (pp. 391-416). Buffalo, NY: Bearly Limited. [ Links ]

9. Pringle, P., and Kirkland, D. (2002). Crossing cultures: Training effects on the divergent thinking attitudes of Spanish-speaking South American managers. Creativity Research Journal, 14 (3-4), 395-408. [ Links ]

10. Bentley, J.C. (2002). New wine in old bottles: The challenges of developing leaders in Latin America. In C. Brooklyn-Derr, S. Roussillon, and F. Bournois (Eds.), Cross-cultural approaches to leadership development (pp. 29-50). Westport, CT: Quorum Books. [ Links ]

11. Berg, B.L. (2001). Qualitative research methods for the social sciences (4th ed.). Massachusetts: Allyn and Bacon. [ Links ]

12. Burnside, R.M., Amabile, T.M., and Gryskiewicz, S.S. (1988). Assessing organizational climates for creativity and innovation: Methodological review of large company audits. In I. Yuji and R.L. Kuhn (Eds.), New directions in creative and innovative management: Bridging theory and practice (pp. 169-185). Cambridge, MA: Ballinger Publishing Company. [ Links ]

13. Cabra, J. (2006). An exploratory examination of creative climate expectations among Colombian managers, supervisors and front-line employees and subsequent development of a measure to assess creative climate. An unpublished doctoral thesis, the University of Manchester, Manchester, United Kingdom. [ Links ]

14. Cabra, J., Talbot, R.J., and Joniak, A.J. (January-June, 2005). Exploratory study of creative climate: A case from selected Colombian companies and its implications on organizational development. Cuadernos de Administración, 18 (29), 53-86. [ Links ]

15. Charness, G. and Haruvy, E. (2000). Self-serving biases: Evidence from a simulated labour relationship. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 15(7), 655-667. [ Links ]

16. Child, J. (1981). Culture, contingency, and capitalism in the cross-national study of organizations. In L.L. Cummings and B.M. Staw (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior (vol. 3, pp. 303-356). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. [ Links ]

17. Covey, S.R. (1989). The 7 habits of highly effective people: Powerful lessons in personal change. New York, NY: Fireside. [ Links ]

18. Davidson, A.R., Jaccard, J.J., Triandis, H.C., Morales, M.L., and Díaz-Guerrero, R. (1976). Cross-cultural model testing: Toward a solution of the etic-emic dilemma. International Journal of Psychology, 11(1), 1-11. [ Links ]

19. Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística (May 31, 2007). Boletín de prensa, abril, 2007. Recuperado el 5 de junio de 2007, de http://www.dane.gov.co/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=474 [ Links ]

20. Ekvall, G. (1996). Organizational climate for creativity and innovation. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 5, 105-123. [ Links ]

21. Farzad, R. (May 28, 2007). Extreme investing: Inside Colombia. BusinessWeek, pp. 50-58. [ Links ]

22. Fitch, K.L. (1998). Speaking relationally: culture, communication, and interpersonal connection. New York, NY: The Guildford Press. [ Links ]

23. Hampden-Turner, C., and Trompenaars, F. (2000). Building cross-cultural competence: How to create wealth from conflicting values. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. [ Links ]

24. Higgins, J.M. (1994). The management challenge (2nd ed.). New York, NY: MacMillin Publishing Company. [ Links ]

25. Hofstede, G. (2001). Cultures consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and organizations across nations (2nd ed.) Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

26. Isaksen, S.G., Lauer, K.L., Ekvall, G., and Britz, A. (2000-2001). Perceptions of the best and worst climates for creativity: Preliminary validation evidenced for the situational outlook questionnaire. Creativity Research Journal, 13(2), 171-184. [ Links ]

27. Jorgensen, J.J., Hafsi, T., and Kiggundu, M.N. (1986). Towards a market imperfections theory of organizational structure in developing countries. Journal of Management Studies, 23(4), 417-442. [ Links ]

28. Lee, B. (1997). The power principle. New York, NY: Simon Schuster. [ Links ]

29. Lemons. M.A. and Jones, C.A. (2001). Procedural justice in promotion decisions: Using perceptions of fairness to build employee commitment. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 16(4), 268280. [ Links ]

30. Maslow, A. (1971). The farther reaches of human nature. New York: Viking. [ Links ]

31. Mayor, A. (1992). Institucionalización y perspectivas del taylorismo en Colombia: conflictos y subculturas del trabajo entre ingenieros, supervisores y obreros en torno a la productividad, 1959-1990. Boletín Socioeconómico (24-25), 203-242. [ Links ]

32. Miles, M.B. and Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

33. Novak, M. (1993). The catholic ethic and the spirit of capitalism. New York, NY: The Free Press. [ Links ]

34. Ogliastri, E. (1998). Culture and organizational leadership in Colombia: The globe study. An unpublished manuscript. [ Links ]

35. Dávila, C. (1987). The articulation of powerand business structures: A study of Colombia. In M. Mizruchi and M. Schwartz (Eds.), Intercorporate relations: Structural analysis of business (pp. 233-263). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

36. Osborn, A. F. (1953). Applied imagination (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Scribner's Sons. [ Links ]

37. Peng, T.K., Peterson, M.F., and Shyi, Y.P. (1991). Quantitative methods in cross-cultural management research: Trends and equivalence issues. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 12 (2), 87-108. [ Links ]

38. Peterson, M.F. and Smith, P.B. (1997). Does national culture or ambient temperature explain cross-national differences in role stress? No sweat! Academy of Management Journal, 40 (4), 930-946. [ Links ]

39. Pierce, J.L, Gardner, D.G., Cummings, L.L., and Dunham, R.B. (1989). Organization-based self-esteem: Construct definition, measurement, and validation. Academy of Management Journal, 32(3), 622-648. [ Links ]

40. Puccio, G.J., Murdock, M. and Mance, M. (2006). Creative leadership: Skills that drive change. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

41. Puyana García, G. (2000). ¿Cómo somos los colombianos?: reflexiones sobre nuestra idiosincrasia y cultura. Bogotá: Quebecor World. [ Links ]

42. Recht, R. and Wilderom, C. (1998). Latin America's dual reintegration. International Studies of Management and Organization, 28 (2), 3-17. [ Links ]

43. Roberts, K. H. (1970). On looking at an elephant: an evaluation of cross-cultural research related to organizations. Psychological Bulletin, 74, 327350. [ Links ]

44. Rodríguez Estrada, M. and Escobar Borrero, R. (1996). Creatividad en el servicio: una estrategia competitiva para Latinoamérica. México: McGraw Hill. [ Links ]

45. Rubin, H. J. and Rubin, I. S. (1995). Qualitative interviewing: The art of hearing data. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

46. Rust, R. T. and Cooil, B. (February, 1994). Reliability measures for qualitative data: Theory and implications. Journal of Marketing Research, 31, 1-14. [ Links ]

47. Schimmack, U., Radhakrishnan, P., Oishi, S., Dzokoto, V., and Ahadi, S. (2002). Culture, personality, and subjective well-being: Integrat-ing process models of life satisfaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(4), 582-593. [ Links ]

48. Schutz, W. (1994). The human element. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Inc. [ Links ]

49. Shkodriani, G.M. (1998). Individualism-collectiv-ism and work values among employees in Mexico and the United States. An unpublished doctorate dissertation, Saint Louis University, St. Louis, Missouri. [ Links ]

50. Strauss, A.L. and Corbin, J. (1990). Basic qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. London: Sage. [ Links ]

51. Sudarsky, R.J. (1992). El impacto de la tradición hispánica en el comportamiento empresarial latinoamericano. Monograph no. 29, Bogotá: Universidad de los Andes, Facultad de Administración. [ Links ]

52. Thomas, K.W. and Kilmann, R.H. (1974). Thomas-Kilmann conflict mode instrument. Tuxedo, NY: Xicom. [ Links ]

53. Triandis, H.C., Marin, G., Lisansky, J. and Betancourt, H. (1984) Simpatia as a cultural script of Hispanics, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47(6), 1363-1375. [ Links ]

54. Trompenaars, F. (1994). Riding the waves of culture. Chicago: Irwin. [ Links ]

55. Vai-Lam, M. (1995). The economics of envy. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 26, 311-336. [ Links ]

56. Universia (January, 2006). El salario mínimo. Recuperado el 1 de febrero de 2007, de http://www.universia.net.co/index2.php?option=com_content&do_pdf=1&id=409. [ Links ]

57. Véliz, C. (1994). The new world of the Gothic Fox: Culture and economy in English and Spanish America. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. [ Links ]

58. Weiss, A. (1994). La empresa colombiana entre la tecnocracia y la participación: del taylorismo a la calidad total. Bogotá: Department of Sociology, Universidad Nacional. [ Links ]