Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Cuadernos de Administración

Print version ISSN 0120-3592

Cuad. Adm. vol.27 no.48 Bogotá Jan./June 2014

Technological capability and development of intellectual capital on the new technology-based firms*

Capacidad tecnológica y desarrollo de capital intelectual en nuevas empresas de base tecnológica

Capacidade tecnológica e desenvolvimento de capital intelectual em novas empresas de base tecnológica

Julio César Acosta-Prado**

Eduardo Bueno Campos***

Mónica Longo-Somoza****

*Este artículo es producto de la investigación "Intellectual capital reports on new-technology-based firms: A strategic diagnostics on intangible assets" financiado por el Instituto Madrileño de Desarrollo (IMADE) y dirigido por la Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, 2008-2009. El artículo se recibió el 25-10-13 y se aprobó el 08-04-14. Sugerencia de citación: Acosta P., J., Bueno C., E. and Longo S., M. (2014). Technological capability and development of intellectual capital on the new technology-based firms. Cuadernos de Administración, 27 (48), 11-39.

**Doctor en Dirección y Organización de Empresas de la Universidad Autónoma de Madrid. Profesor de la Universidad Externado de Colombia. Correo electrónico: julioc.acosta@uexternado.edu.co

***Doctor en Ciencias Económicas y Empresariales de la Universidad Complutense de Madrid. Profesor de la Universidad a Distancia de Madrid. Correo electrónico: eduardojavier.bueno@udima.es

****Doctora en Contabilidad y Organización de Empresas de la Universidad Autónoma de Madrid. Profesora de la Comunidad de Madrid. Correo electrónico: monica.longo09@gmail.com

Abstract

This article analyses the relationship between technological development and intellectual capital. Creativity and the appropriate use of knowledge are fundamental sources of technological development. They in of themselves represent the intellectual capital of companies, and lead to competitive advantage. This article argues that when technology is developed and exploited, drawing on acquired knowledge, the intellectual capital of a company is utilized and therefore enhanced. The empirical study is conducted, by the case study methodology in 35 New-Technology-Based Firms (NTBFs) at Madrid Scientific Park (PCM) and Leganés Technological Science Park (LEGATEC), located in the Community of Madrid, Spain.

Keywords: Technological capability, intellectual capital, technological capital.

JEL Classification: D83, M19, O32.

Resumen

Este artículo analiza la relación entre la capacidad tecnológica y el capital intelectual. La creación y explotación del conocimiento son la fuente fundamental de la capacidad tecnológica de las empresas y del capital intelectual, así como también de las ventajas competitivas. Aquí se argumenta que cuando se crean y explotan las capacidades tecnológicas, recurriendo a procesos de conocimiento, también se crea y explota el capital intelectual de la empresa. En el análisis empírico se aplicó el método de estudio de casos a 35 nuevas empresas de base tecnológica (NEBT) del Parque Científico de Madrid (PCM) y el Parque Científico Leganés (LEGATEC), en la Comunidad de Madrid, España.

Palabras clave: Capacidad tecnológica, capital intelectual, capital tecnológico.

Clasificación JEL: D83, M19, O32.

Resumo

Este artigo analisa a relação entre a capacidade tecnológica e o capital intelectual. A criação e exploração do conhecimento são a fonte fundamental da capacidade tecnológica das empresas e do capital intelectual, bem como das vantagens competitivas. Aqui, argumenta-se que, quando se criam e exploram as capacidades tecnológicas recorrendo a processos de conhecimento, também se cria e explora o capital intelectual da empresa. Na análise empírica, aplicou-se o método de estudo de casos a 35 novas empresas de base tecnológica (NEBT) do Parque Científico de Madri (PCM) e do Parque Científico Leganés (LEGATEC), na Comunidade de Madri, Espanha.

Palavras-chave: Capacidade tecnológica, capital intelectual, capital tecnológico.

Classificação JEL: D83, M19, O32.

Introduction

In this paper we focus on the study of the relationship between Technological Capabilities and Intellectual Capital on organizations. In the current knowledge-based-economy (Hayek, 1945; Conner and Prahalad, 1996; Grant, 1996; Kogut and Zander, 1996; Spender, 1996; Drucker, 2001), the processes of creating and exploiting knowledge in the firm constitute a key source of Technological Capability, Intellectual Capital and, so, they are also a source of getting competitive sustainable advantages (Teece et al., 1997; Grant, 1996; Spender, 1996). Therefore, this paper studies that when the members of an innovative firm create and exploit their firm's Technological Capabilities using social processes of knowledge, simultaneously, they are creating and exploiting the firm's Intellectual Capital which lead them to get competitive advantages and higher incomes. To study this relationship we have made a theoretical proposal about firms' Technological Capabilities and Technological Capital and we have selected a sample of new-technology-based firms to test the proposal because, in the current knowledge-based economy, this kind of firms have a relevant role as innovative organizations that create and exploit Technological Capabilities.

This way, we cannot avoid emphasizing the importance of knowledge as a key ingredient of technology (Prahalad and Hamel, 1990), for it plays a crucial role in those processes of creation of technological basis value (Nelson, 1991; Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995; Sánchez and Mahoney, 1996). Besides, in the actual economic crisis context and quick changeable environment, it is of high importance for firms and countries to find the way back to the economic growth and to make efforts in stimulating the knowledge processes and, as a result, the innovation and competitiveness (Schumpeter, 1939; European Commission, 2003; Hill and Jones, 2010).

The fact of considering Technological Capabilities as a key element for business success leads us to strategic approaches of the firm as Resource-Based View (Wernerfelt, 1984; Barney, 1991; Grant, 1991); Dynamics Capabilities (Teece and Pisano, 1994; McGrath et al., 1995; Teece et al., 1997; Eisenhardt and Martin, 2000; Teece, 2009) and Knowledge-Based Theory (Kogut and Zander, 1992; Nonaka, 1994; Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995; Zander and Kogut, 1995; Grant, 1996; Spender, 1996; Spender and Grant, 1996). These approaches, alternatively of the Industrial Economy (Porter, 1980), show that we must look for those variables that better explain the end results of the firms at the very heart of these organizations.

From this perspective, we base our proposal on the analysis of two fundamental questions. On the one hand, on the analysis of the characteristics of the different resources that are considered a source of competitive advantages (Wernerfelt, 1984; Barney, 1991; Grant, 1991; Hall, 1992; Amit and Schoemaker, 1993; Peteraf, 1993) and on the other hand, on the analysis of the processes and organizational routines that make possible to accumulate and exploit the new resources and relevant Technological Capability needed to face all the menaces and opportunities from a dynamic environment (Teece et al., 1997; Cool et al, 2002; Grant, 2002; Acosta-Prado et al., 2013). From this point of view, we define a firm as an entity of learning, which sustained success depends on its capability for speeding up and effectively renew its knowledge stock (Nelson and Winter, 1982).

Despite all the multiple references in literature, there is still no consensus about the specific qualities of the strategic resources or about the processes needed for their efficient development (Kristandl and Bontis, 2007). The current paper tries to move forward in the study of these subjects and, more specifically, analyzes the processes through which the different organizations can improve the management and renewal of their Technological Capability.

The 35 new technology-based firms of the sample are companies created at the Madrid Science Park and the Leganés Science Park in Madrid, Spain. They are small and micro firms (European Commission, 2003) in a process of development. We choose these firms because they have been recently founded and they asked for technical assistance in order to understand "how to innovate" as well as to develop successful ways of work in their critical first years, so, they collaborated intensely in the research. Moreover, these firms are knowledge-intensive, are based on the exploitation of an invention or technological innovation, and employ a high proportion of qualified employees. Therefore, these firms are suitable to study the Technological Capabilities which are developed by firms knowledge-intensive. We follow the definitions of NTBF proposed by Butchart (1987) and Shearman and Burrell (1988) and the definition of small and micro firms adopted by the European Commission in 2003. These definitions are stated in section "Research approach and methods".

The contribution of our analysis is both theoretical and practical: Theoretical, because we propose a conceptual definition of Technological Capability, a classification of it and, also, we propose a theoretical relationship between Technological Capabilities and Intellectual Capital, specifically the Technological Capital. Moreover we treat two relevant elements in organizational literature that have rarely been investigated empirically together before: Technological Capabilities and Intellectual Capital. Practical, because the findings of our empirical analysis would help innovation firms' stakeholders to understand the processes of creating and exploiting knowledge in the firm which constitute the key source of Technological Capability and Technological Capital and make decisions accordingly in order to get sustainable competitive advantages and, so, success in a quickly changeable environment.

As it was mentioned before, in this paper, we investigate that during process of creating and exploiting the Technological Capabilities, innovative firms also create and exploit their Technological Capital, that is, a kind of Intellectual Capital (Acosta-Prado and Longo-Somoza, 2013, Bueno et al, 2010a; Bueno et al, 2010b). To get the aim of this paper we proceed as follows. In the first section, we carry out a conceptual analysis of the Intellectual Capital, specifically, Technological Capital, and its measure in the Intellectus Model, a model of identification and measurement of Intellectual Capital (Bueno and CIC, 2002; 2012). Therefore, in this section we set up the theoretical propositions about two concepts: Technological Capital and Technological Capability. We review the concept of Intellectual Capital, the variables to measure it, the concept of Technological Capability and the research approaches, as point of reference to choose the proper one for our empirical research. In the second section, we propose a theoretical relationship between Technological Capital and Technological Capability by analysing the Technological Capability and their characterization and its relationship with the Intellectual Capital through the knowledge processes which create and develop these two elements. The third section shows the research issue which is based on the theoretical background stated before. Following, we present the research approach and method where we detail the case study methodology we used and the selected sample. Next, it is analyzed the empirical evidence of how are created and exploited the Technological Capabilities and the Technological Capital of those NTBFs of the sample. Later, we discuss the conclusions and implications of the research, and, finally they are shown the limitations and future research directions.

1. Theoretical foundations

1.1 Intellectual capital: Technological capital in the intellectus model

In the last decade of the 20th century a great interest in knowledge management emerged as a way of levering the strategically relevant knowledge for the organization (Teece, 2000). Nowadays traditional tangible assets continue being important to produce goods and services. Nevertheless, knowledge has become a key asset to manage in order to gain a sustainable competitive advantage (Boulton et al., 2000; Low, 2000; Lev, 2001) and wealth creation (Edvinsson and Malone, 1997; Stewart, 1997). Firm's environment changes quickly and, in this context, knowledge turns into a key resource to take advantage of the opportunities that changes may bring.

Definitions of Intellectual Capital (IC) were proposed in 1990s by authors as Edvinsson and Malone (1997), Roos et al. (1997), Stewart (1997) and Sveiby (1997). IC is generally defined as the intellectual material that can be put to use to create wealth. It includes organization's processes, technologies, patents, employees' skills and information about customers, suppliers and stakeholders (Stewart, 1997). The categories for IC differ slightly among researchers (Kaufmann and Schneider, 2004), however internationally they are accepted three basic dimensions: Human, Relational and Structural Capital (Bueno and CIC, 2002).

Human capital is concerned with the accumulated value or wealth generated by the values, knowledge and abilities of people (Human Intelligence) and it represents the stock of knowledge within an organization rather than in the minds of individual employees (Bontis et al., 2002). Structural capital expresses the accumulated value or wealth generated by the value of the existing knowledge, which is property of the organization that generates its knowledge base. This knowledge is the combination of shared values, culture, routines, protocols, procedures, systems, technological developments and intellectual property of an organization which make up the collective know how and which remain in the entity whether people leave (organizational intelligence). Relational capital expresses the accumulated value or wealth generated by the value of the knowledge which comes to the organization through the relationships and actions shared with external or social agents (Social and competitive intelligence) and it refers to customers, social capital, and stakeholders (Stewart, 1997; Johanson et al., 2001; Bukh, 2003; Ordoñez, 2003).

Within Relational Capital it is necessary to distinguish between Business Capital and Social Capital. The former is directly related to the agents linked to the business process, and the latter is connected with the remaining agents (Coleman, 1988; Nahapiet and Ghoshal, 1998; McElroy, 2001; Bueno, 2002).

Also, within structural capital it is necessary to distinguish between organizational capital and technological capital. The organizational capital is a combination of intangibles that structure and develop the organizational activity. The technological capital is a combination of intangibles directly linked to the development of activities and functions of the technical system of the organization's operations which is responsible for obtaining products, developing efficient production processes and advancing the knowledge base necessary for future innovations in products and processes.

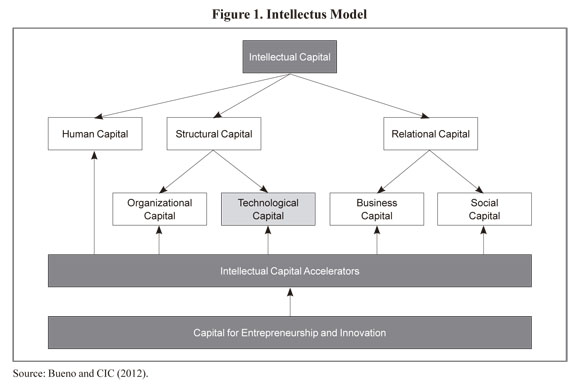

The Intellectus Model is a model of identification and measurement of intellectual capital or intangible assets. The two structures described of Relational Capital and Structural Capital were incorporated to the Intellectus Model for the measurement and management of intangible assets (Bueno and CIC-IADE, 2002; 2012). This model starts from a tree development which clarifies the interrelationships between the various intangible assets of the firm through the identification of four levels of aggregation: components, elements, variables and indicators (figure 1). The ability of the Intellectus Model to assess and measure Intellectual Capital resides in its capacity to adapt to the needs of each firm, because of its systemic, open, dynamic, flexible, adaptive and innovative nature.

Focusing our attention on the Technological Capital, relevant to test the research issue of this paper, the Intellectus Model proposes the following elements or homogenous groups of intangible assets to be measured and managed: Effort in Research and Development and Innovation (R&D&I); Technology Infrastructure; Intellectual and Industrial Property and Result of Innovation. These groups or elements are made of variables or intangible assets integrated within one of the groups (Bueno and CIC, 2012):

- Effort in R & D & I: Refers to the efforts made in technological innovation processes.

- Technological infrastructure: Combination of knowledge, methods and techniques which the Organization incorporates into its processes so that they are more efficient and effective.

- They are accumulated through external sources.

- Intellectual and industrial property: Legally protected knowledge which grants the firm which created it the exclusive right to its exploitation in a predetermined time and area.

- Technological surveillance: A set of tools, techniques to capture technological information outside the organization that expresses the ability to analyze it and convert into knowledge for decision-making to facilitate anticipate change and sustain competitive advantage. Is also known as competitive intelligence or organizational intelligence processes to cope with change, turbulence and uncertainty of the environment.

When people commit themselves with organizations and contribute with their knowledge, firms acquire this knowledge which can become technology if it is developed and transmitted. Therefore, individual knowledge can be transformed into social or collective knowledge and shared by the members of an organization when transferred through oral or written language that is through knowledge processes (Argyris and Schõn, 1978; Quinn, 1992; Von Krogh and Roos, 1995; Spender, 1996; De Geus, 1997; Cook and Brown, 1999; Bueno, 2005; Bueno et al., 2010b).

People learn by participating in communities where knowledge circulates in many ways. It circulates through articles or written procedures, and also through unwritten artefacts such as stories, specialized language, and common wisdom about cause-effect relationships. People observe and discuss for example informal work routines and, doing so, they exchange their experience, make sense of the information and share and use their knowledge. Levering and managing knowledge involves getting people together in order they share insights they do not know they have. Through this social process of interaction and communication, members of the community create and expand knowledge (Nonaka, 1994; Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995; Polanyi, 1969). In innovative firms, these knowledge processes construct and develop their Intellectual Capital or intangible assets (Acosta-Prado and Longo-Somoza, 2013, Bueno et al, 2010a; Bueno et al, 2010b).

1.2 Technological capability: Characterization and classification

During the decade of the eighties of last century, the traditional notion about how competitive advantage can be achieved through setting up in appealing markets and introducing three generic strategies as leadership in costs, differentiation and segmentation (Porter, 1980) is initially questioned. It is when reintroducing some strategic approaches based on the existence of distinctive competences (Selznick, 1957; Penrose, 1959, Ansoff, 1965), when comes up the perspective of a firm based on the resources and capabilities over which competitive advantage can be built (Wernerfelt, 1984; Barney, 1991; Grant, 1991; Amit and Schoemaker, 1993).

This approach implies that a firm must try to "know itself", through a deep understanding of its own strategic resources, in order to be able to formulate a strategy for exploiting them and developing those resources needed for the future. We must add to this perspective the approach on dynamic capabilities (Teece et al., 1997; Eisenhardt and Martín, 2000), which assumes the dynamic character of the environment and the need for adapting to it through the permanent development of new resources and Technological capabilities.

In view of turbulent environments, with high doses of uncertainty and complexity, global competition, shortening of the products' life cycle and sudden changes on the likes and needs of the consumers, the firm has indeed problems to decide which needs want to satisfy although that doesn't mean the firm cannot ask itself -alternatively- which of those needs can be satisfied. In this case, external orientation cannot be the only foundation for business strategy, but also an internal analysis of the available resources and capabilities in order to set up a strategy.

This dynamic conception of the theory of resources and capabilities attaches great importance to innovation in business, Technological capabilities remain one of the most effective instruments in neutralizing the threats and exploit opportunities offered by the environment, as shown by numerous empirical works (DeCarolis and Deeds, 1999; Balconi, 2002; Figuereido, 2002; Zahra and Nielsen, 2002; DeCarolis, 2003; Nicholls-Nixon and Woo, 2003; Douglas and Ryman, 2003; García and Navas, 2007; Martin et al., 2011; Trillo and Fernández, 2013; Ruiz-Jiménez and Fuentes-Fuentes, 2013).

From the conceptual distinction between resource and capability (Grant, 1991), Technological Capability is defined as any general power of the firm, knowledge-intensive, to jointly mobilize different scientific resources and individual technicians, which allows the development of products and/or innovative and successful production processes, serving the implementation of competitive strategies that create value in view of certain environmental conditions (Garcia and Navas, 2007).

This suggests that the Technological Capability it means the ability to develop and refine the routines that facilitate combining existing knowledge and to disseminate new knowledge gained through the organization and incorporate it into new products, services and/or production processes (Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995; Grant, 1996, Winter, 2003).

Based on these considerations, Technological Capability is defined as follows: all of the generic powers of a knowledge-intensive firm to mobilize individual technoscience resources that successfully foster improvement or creation of new products and innovative production processes. The objective is the implementation of competitive strategies that create value under certain environmental conditions (Acosta, 2009 y 2010; Acosta-Prado and Longo-Somoza, 2013).

From the general definition of Technological Capability, as mentioned above, we provide a Technological Capability classification because it does not always affect in the same way the innovative processes. Therefore, we propose a classification of Technological Capabilities that goes beyond the scope of what is conceptual in terms of academic and managerial implications.

Among other proposals in the literature, from the input of March (1991) and Levinthal and March (1993), we have chosen to classify Technological Capabilities based on the nature of knowledge flows, distinguishing between operating and exploring, according to the degree of novelty of the innovation developed, the risk assumed in such processes and the possible and more or less immediate application in the markets for these technological advances (García and Navas, 2007).

More specifically, these authors define Technological Capabilities as a strategic exploration of knowledge-intensive systems responsible for the collection of radical innovations, which become technological designs with a dominant position for a certain period of time. On the other side, the Technological Capabilities of strategic operation are responsible for obtaining successive incremental innovations that improve some of its attributes, until there occurs a shift towards a new technological regime.

According to Levinthal and March (1993) exploration involves the search for knowledge of facts that can be known. For its part, operation refers to the use and development of facts already known. Exploration involves the innovation, novelty seeking and risk taking, and performing all those activities geared towards the discovery of new opportunities. For its part, the operation involves the upgrading of the available technology, the "learning by doing", the improvement in the division of labor and all the activities associated with the pursuit of efficiency.

Although these two activities are essential for organizations, it is also true that compete for scarce resources. In this regard, certain practices associated with the exploration and exploitation of knowledge can sometimes be incompatible. As a result, organizations must make explicit and implicit choices between both options (March, 1991). Avoiding areas of conflict will require a compromise solution or incorporating a combination of both, that might even be used simultaneously in different parts of the organization. Therefore, maintaining a balance between exploration and operation (Levinthal and March, 1993; Zack, 1999; Grant, 2002; Ichijo, 2002) is a key factor for survival and competitive success.

In other words, the exploration and operation of technological knowledge are the result of an exchange process between the environment incentives, the existing knowledge in the organization and the actions of its members, and such knowledge and actions are input and output in the conversion flows and change in the knowledge stocks. This leads us to a new perspective on Technological Capabilities and to understand the dynamic potential of creation, assimilation, dissemination and use of knowledge by means of flows that make possible the training and assessment of stocks of knowledge, training the organization and the people, flows which are made up of to act in changing environments (March, 1991).

Certainly, the stocks of knowledge affect the perception and understanding of reality, but if reality changes then it will be necessary to renew the knowledge base for the firm to suit the new conditions of the environment, through flows of knowledge. Thus, the knowledge flows incorporating both cognitive and behavior changes and providing the means to understand how the body of knowledge in the organization evolves through time, increasing its range and adaptability (Von Krogh and Vicari, 1993; Carmeli and Azeroual, 2009; Ruiz and Fuentes, 2013).

The proposed classification of Technological Capabilities is important, as the uneven nature of the knowledge which flows in each case, exploration and operation, will require different decisions regarding the disposition and use of resources and capabilities of the business and market opportunities.

Therefore, the innovative firms develop Technological Capabilities of exploration and operation, or exploitation, through the mobilization of resources techno-science for the improvement or creation of new products and innovative production processes successfully. The processes involved in this development are knowledge processes that make possible to accumulate and exploit the new resources and relevant Technological Capability needed to face all the menaces and opportunities from a dynamic environment (Teece et al, 1997; Cool et al, 2002; Grant, 2002; Bueno et al., 2010a; Acosta-Prado and Longo-Somoza, 2013). The Technological Capabilities developed can be classified as follows (Acosta, 2010; Bueno et al., 2010a; Acosta-Prado et al., 2013):

- Investments to acquire knowledge used to develop very specific activities.

- Use of knowledge derived from database, patents, etc, used to develop technologically improved or new products and services and which requires the utilization of different technologies.

- Easy storage of technological knowledge in soft, hardware or documents.

- Acquisition of knowledge through the hiring of qualified staff, through the relations with other firms and which involves a high degree of novelty and it is easily codified.

2. Theoretical relationship between technological capital and technological capability

The fact of relating the technological capability and the technological capital, a kind of intellectual capital, includes a broad range of activities or knowledge processes within firms, which help to generate new knowledge or improve the existing ones (Acosta and Longo, 2013, Bueno et al, 2010a y 2010b). This knowledge is applied to the procurement of new goods and services and new forms of production (López et al, 2004). This is determined by the relationship between organizational characteristics and their outcomes and by the identification and sustainability of the organizational change, as well as the adaptation of the conditions, context and resources that make more efficient and faster the production of innovations facilitating the resolution of problems, fostering personal engagement and approaching these actions towards the creation of competitive advantage.

In this context, Rogers (1996) relates the development of technological capability and technological capital, through the concept of innovation of knowledge, understanding that innovation is an informational process in which knowledge is acquired, processed and transferred (Escorsa and Maspons, 2001). Thus, the organization must recognize and seize new opportunities through the creation and use of the knowledge needed to develop technological capability and split the existing ones (Hamel and Prahalad, 1993; Woolley, 2010).

For Aragon et al. (2005), this relationship comes after the use of a specific technology, as a means to introduce a change in the firm, and they call this link innovation. This approach highlights the importance of linking technology to the organization both through its implementation, design and development, as well as through the underlying philosophy or culture of innovation (Orengo et al, 2001).

Therefore, technological innovation is a process through which the firm may involve deeper changes in scientific and technological advances (Benavides, 1998), incorporated into new products and/or production processes carried out in order to adapt to the environment and create sustainable competitive advantages (Lopez et al., 2004).

Understanding technological innovation has led some authors to describe the phenomenon as a technological change, referred to the provision and use of technologies (Friedman, 1994) and the allocation of areas such as dynamism, specificity, interaction and social aspects to human action in the organizational context.

It should be noted that the coexistence of the terms used in the present, technological innovation and technological change, does not mean confrontation between them. Thus, West and Farr (1990) suggest that certainly any kind of innovation, in terms of organization, is a change, although not every change is innovation. Thus, technological innovation is a dimension of organizational change that reflects the intent of obtains a benefit, based on the development and operation of strategic technological intangibles which determine the innovating outcome (Cohen and Walsh, 2000; Cohen et al., 2002; Woolley, 2010; Ruiz and Fuentes, 2013; Bueno, 2013).

The development of technological capability is the result of a lengthy process and of the accumulation of knowledge within the firm that may be affected by facilitating factors or inhibitors of these capabilities (Cohen and Levinthal, 1990), process which involves both the effects of appropriation and obtaining knowledge (Nieto and Quevedo, 2005) and the protection of competitive results (Cassiman and Veugelers, 2002). Therefore it is necessary to develop a strategy in order to promote the proper exploration and operation of the technological capability that lead to new and innovative forms of competitive advantage, given a specific temporal dependence and a market position (Leonard, 1993).

Dawson (2000) states that development of technological capability of a firm principally depend of four aspects: The individual technology, organizational technology, behaviors and skills of individuals and organizational skills and behaviors. Bollinger and Smith (2001) suggest that the development of technological capability is a valuable resource for those firms wanting to innovate and compete, as firms need to know which strategic assets they hold and which ones are crucial for obtaining a sustainable competitive advantage. In this particular, Meso and Smith (2000) propose two points of view -technical and sociotechnical- in order to understand both the emergence of strategic assets and the knowledge transfer between employees and the firm and vice versa. The technical perspective is associated with the use of information technologies to support knowledge creation in the firm (e.g., databases, documentation systems, search and data mining systems, teams' decisions support systems, corporate portals, etc.). The socio-technical perspective recognizes that the interdependent and complementary nature of knowledge should enable the firm assess the strategic relevance of its knowledge assets, and be able to establish the strategy that, in its business environment, leads to the formation of the most suitable knowledge base for achieving sustainable competitive advantages. Finally, they conclude that firms that only operate the tangible aspects of knowledge do not have a competitive advantage.

DeCarolis and Deeds (1999) examine the relationship between knowledge and performance in the biotechnology industry. The accumulation of knowledge is the result not only of the internal developments but also the assimilation of external knowledge. While making operational the knowledge flow they took into account three variables: location, alliances and R&D spending. Regarding inventories of organizational flows they took the following variables: Products in stage of development, firms' patents and researches. They concluded that the management of stocks and flows of knowledge seems to be something special to succeed. In any case, additional empirical investigations are needed to improve understanding between knowledge-intensive technological capabilities and business performance.

Other authors as Acosta and Longo (2013), Bueno et al. (2010a; 2010b) and Bueno (2013) state that there is a relation between the social processes of interaction to create and develop the intellectual capital and the ones focus on creating and developing the technological capabilities. These kinds of firms hire a high proportion of qualified employees and researchers that think the best way to explore and exploit an invention and technological innovation, to do it they work in group, exchanging and sharing knowledge between all members through conversations. To facilitate these processes, they promote informal relations and design formal channels of communication, and the construct and develop simultaneously their intellectual capital and technological capability.

To sum up, the literature review made in this section points out that it exists a relationship between the technological capability and the intellectual capital in the innovative firms because they are created and developed by knowledge processes. These processes involve the accumulation of knowledge within the firm, the assimilation of external knowledge, the individual technology, the organizational technology, the behaviors and skills of individuals and organizational skills and behaviors.

3. Research issue

The preceding section suggests that the processes of creating and exploiting knowledge in innovative firms constitute the key source of technological capability and technological capital and, so, these processes are a source of getting competitive sustainable advantages. Grounded in this theoretical relationship we empirically investigate if when innovative organizations carry out processes of creating and exploiting knowledge, simultaneously, they are constructing and developing their technological capability and elements of their technological capital.

Specifically, we investigate the fact that when innovative firms, through social processes of knowledge, construct and develop their technological capability through of the mobilization of resources techno-science for the improvement or creation of new products and innovative production processes successfully, simultaneously, they are also constructing the elements of their technological capital. This interrelationship has been understudied until this moment, however to innovative firms it is interesting to know in order to help organizations to understand "How do innovate?" in order to define their strategy and set the base of their success.

3.1 Research context

In order to test the research issue, the empirical study has been conducted in 35 New-Technology-Based Firms (NTBFs) of the Madrid Scientific Park (PCM) and the Leganés Science Park (LEGATEC), in the Community of Madrid, Spain. They are micro and small firms following the European Commission definition. European Commission definition of micro and small firms was adopted in 2003 in the recommendation C (2003) 1422. A small firm is defined as "an enterprise which employs fewer than 50 persons and whose annual turnover and/or annual balance sheet total does not exceed EUR 10 million". A micro firm is defined as "an enterprise which employs less than 10 people and whose annual turnover and/or annual balance sheet total does not exceed EUR 2 million".

The term "new technology-based firms" (NTBFs) was coined by the Arthur D. Little Group (Little, 1977). They stated that a NTBF was "an independently owned business established for not more than 25 years and based on the exploitation of an invention or technological innovation which implies substantial technological risks". Also, Butchart (1987) and Shearman and Burrell (1988) defined this kind of firms. They focused on sectors which had higher than average expenditures on R & D as a proportion of sales or which employed proportionately more qualified scientists and engineers than other sectors. This last definition has been widely used however these authors call these firms "high tech SMEs" and they distinguish them from NTBFs which are both newly established and independent. We use both definitions to develop the empirical research on NTBFs established at the Madrid Science Park and the Leganés Science Park. These firms have been established by a group of entrepreneurs, based on exploitation of an invention or technological innovation and employ a high proportion of qualified employees. Therefore, they can be qualified as innovative firms and suitable to test the research issue.

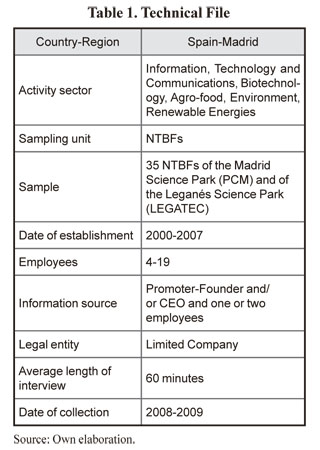

The sample of 35 NTBFs was not random however it reflects a representative selection of this kind of firms established at the Science Madrid Park and Leganés Science Park. The comparison of case studies within the same context enables the "analytic generalization" through the replication of results, either literally (when similar responses emerged) or theoretically (when contrary results emerge for predictable reasons) (Yin, 1984). Thus we ensure that the evidence in one well-described setting is not wholly idiosyncratic (Miles and Huberman, 1984). Although space prevents our providing "thick descriptions" of each case (McClintock et al, 1989), Table 1 makes a brief description of the firms studied at the time of our analysis. The technical file of the empirical study showing the period and average durations of the interviews, the legal entity of the firms, their activity sector, the number of employees and informants or information source. As it is shown in this table, the firms that took part in the empirical study were innovative firms established between 2000 and 2007 as Limited Companies and belong to activity sectors based on the exploitation of an invention or technological innovation. These sectors are: Information, Technology and Communications, Biotechnology and Agro-food and Environment and Renewable Energies. They employ qualified people with a PhD, Master or Bachelor Degree and following the European Commission definition, they are micro and small firms as they have from 4 to 19 employees.

The data-collection process took place in the period 2008-2009. We used several data-collection methods (Eisenhardt, 1989). We collected data through interviews, observations, and secondary sources. The underlying rationale is "triangulation", which it is possible by using multiple data sources providing stronger substantiation of constructs and propositions (Webb et al., 1996).

As it has mentioned in the Introduction section, the criteria for selecting these firms were the following. They had been recently founded and they asked for technical assistance in order to understand "how to innovate" as well as to develop successful ways of work in their critical first years, for that, they collaborated intensely in the research. All of them carried out the identification and measurement of their intellectual capital using the intellectus model. Furthermore, these firms were knowledge-intensive, based on the exploitation of an invention or technological innovation, employed a high proportion of qualified employees and skilled in highly specialized fields. They belonged to different industries, and this allowed us to treat this element as a ceteris paribus variable and to focus on technological capabilities and technological capital shared by them. Therefore, these firms were suitable to study the technological capabilities and its relation with the technological capital which are developed by knowledge-intensive firms.

3.2 Case study methodology

To test empirically the aforementioned research issue we take the strategic approaches of the firm as resource-based view (Wernerfelt, 1984; Barney, 1991; Grant, 1991), dynamics capabilities (Teece and Pisano, 1994; Teece et al., 1997; Eisenhardt and Martin, 2000; Teece, 2009) and knowledge-based theory (Kogut and Zander, 1992; Nonaka, 1994; Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995; Zander and Kogut, 1995; Grant, 1996; Spender, 1996; Spender and Grant, 1996).

The empirical study is conducted by the case study methodology. We use this methodology particularly suitable for answering "how" and "why" questions (Yin, 1984) and that also enables to use "controlled opportunism" to respond flexibly to new discoveries made while collecting new data (Eisenhardt, 1989). With this choice we ensure that the data collection and the analysis meet the tests of construct validity, reliability, and internal and external validity by carefully considering Yin's tactics (1984). Construct validity is enhanced by using the multiple sources of evidence (interviews, observations and secondary data sources) and by establishing a chain of evidence when we concluded the interviews. Reliability was promoted by: (a) using a case-study protocol in which all firms and all informants were subjects to the same entry and exit procedures and interview questions; (b) by creating similarly organized case data bases for each firm we visited. External validity was assured by the multiple-case research design itself, whereby all cases were NTBFs of Madrid Science Park and Leganés Science Park. Finally, we addressed internal validity by the pattern-matching data-analysis method described in Data Analysis Procedure section.

The case study methodology provided a realtime study of this paper research issue in the natural field setting by investigating 35 new technology-based firms created at the Madrid Science Park and the Leganés Science Park. These 35 firms were of great interest for our empirical work for the reasons already mentioned in the Research Context section: (1) they asked for assistance in order to set the best strategies, structure an procedures to warrant their success in their first years so they offered their collaboration in our research; (2) they employed a high proportion of qualified employees so when analyzing the elements of the technological capital and the technological capability it was easy to make them understand this last emergent concept and its possible relation with IC what made our work as researchers easier and fruitful; (3) they carried out the identification and measurement of their intellectual capital using the intellectus model; (4) and they belong to different industries, what allowed us to treat this element as a ceteris paribus variable and to focus our attention on elements they share as NTBFs.

4. Empirical analysis

4.1 Interviews

It was developed a case-study protocol in order to pursue reliability in the findings. A pilot study was carried out too to refine our data-collection plan with respect to both the content of the data and the procedures followed. The primary source of initial data collection came from semi-structured interviews with fifty two informants which lasted sixty minutes on average per case. To obtain various points of view and to avoid slants these interviews were conducted with several informants in each firm: the Promoter-Founder and/or CEO and one or two employees, all of them qualified people with a PhD, Master or Bachelor Degree. The interviews took the form of focused interviews that remained open-ended and had a conversational manner. We began the interviews by asking the respondents to take the role of spokesperson for the organization to focus on organizational level issues. Following we explained them the concepts of technological capability and technological capital, and also, that the aim of the interview was to study how this capability was being constructed and its relationship with the construction of the technological capital. All the interviews were recorded and transcribed immediately afterward (Eisenhardt, 1989).

In order to obtain data about the knowledge processes, the technological capability and the technological capital, we divided the interviews in two stages. In the first stage of the interviews we asked the respondents global aspects of the firm such as: To describe his or her job in the firm, open questions about the history of the firm, activity sector, structure, core characteristics, strengths, customers, relations with the Scientific Park and other firms. In the second stage of the interview we focused on areas such as the feeling of being a community, ways of share, storage and protect knowledge, climate between members, business philosophy, share values, the communications ways between them, departments or formal functions, infrastructures and financial support.

4.2 Observations and secondary sources

We used secondary sources to collect background information about the NTBFs of the sample. Such sources included annual reports, internal documents provided by the interviewees, agendas for meetings, minutes of past meetings, internal newsletters and intranets, industry reports, websites, and articles in magazines and newspapers about the situation and evolution of the industry in general and of the 35 NTBFs in particular. Beside, we reviewed in all of them the reports of the identification and measurement of their technological capital using the intellectus model. Also, along the visits to the firms, we kept a record of our impressions and observations we made when we participated in activities such as coffee breaks and lunches. Whenever possible, we attended meetings as passive note-takers. These observations provided real-time data. The impressions and observations were related with the knowledge processes and their results. We used the secondary sources and data to supplement the data obtained from the interviews.

4.3 Data analysis procedure

To analyze the collected data we set the general analytic strategy called "relying on theoretical propositions" (Yin, 1984). To follow this strategy first we described the theoretical propositions about the concepts of technological capital and technological capability in sections Theoretical foundations and Theoretical relationship between technological capital and technological capability. Second, these theoretical propositions will be the guide to analysis the empirical evidence (see Findings section) to answer the research question stated in the Research issue section. Also, we have followed the explanation-building data-analysis method, which is a special type of pattern-matching method. We have chosen this method to analyze data because it is a relevant procedure for explanatory case studies where casual links are in narrative form (Yin, 1984).

To sum up, the final explanation of the research issue of this multiple-case research is the result of: (1) the theoretical propositions initially established about technological capital and technological capability; (2) an iterative process of comparisons between these propositions and the findings; (3) a continuous revision of the propositions.

As techniques of data-analysis we have used tables which have helped us to put in order and make comparisons between the empirical evidence and to present the relations between data and the theoretical propositions (Miles and Huberman, 1984).

4.4 Findings

The study of the data collected provided a preliminary analysis and an understanding of the relationship between technological capability and technological capital in NTBFs in a phase of development by the identification the entire set of elements of tangible or intangible nature. These overall results are discussed below.

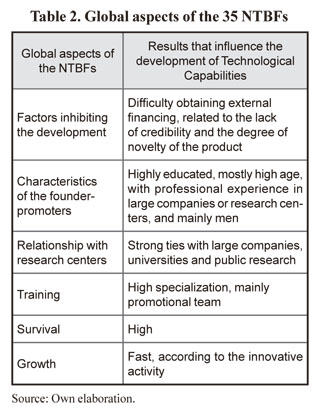

Table 2 presents the global aspects and their results that are common to all the NTBFs investigated.

As seen in Table 2, the empirical evidence shows that NTBFs are firms with high growth and survival, suggesting that these firms are in possession of a competitive advantage and, hence of the appropriation of higher revenues.

The analysis of the data also provided the relevant technological capabilities developed by the NTFBs of the sample. These capabilities are related with:

- Investments to acquire knowledge used to develop very specific activities.

- Use of knowledge derived from database, patents, technical reports, etc.

- Acquisition of knowledge that involves a high degree of novelty.

- Use of the technology which requires the utilization of a combination of different technologies.

- Acquisition of knowledge through the hiring of qualified staff.

- Use of knowledge to develop technologically improved products and services.

- Use of knowledge to develop technologically new products and services.

- Easy storage of technological knowledge in soft, hardware or documents.

Besides, the analysis of the data collected also provided the relevant process of creating and exploiting knowledge, which contribute simultaneously to the construction of the investigated firms' technological capability and technological capital. These processes involve the following factors:

- Factors of intrinsic nature of innovative firms

- Factors of external nature of innovative firms

- Factors of intrinsic nature of innovative firms associated with science parks

- Factors of external nature of innovative firms associated with science parks

Specifically, the factors are enumerated bellow.

The relevant factors of intrinsic nature of NTBFs to the construction of technological capability and the construction of their technological capital are:

- Technological surveillance and adaptation at changing environment

- R&D&I expenses (total sales and total production)

- Specialization of personnel in R&D&I

- Projects in R&D&I

- Purchase of technology

- Infrastructure of production technology

- Infrastructure of information and communication technologies

The relevant factors of external nature of NTBFs to the construction of technological capability and the construction of their technological capital are:

- Relevant customer base

- Generation of cooperation networks

- Permanent updating

- Knowledge of competitors

- Relationships with suppliers

- Relationships with public administration

- Relationships with institutions and investors

Besides, the factors of intrinsic nature of NTBFs, associated with science parks that influence in the construction of technological capability and the construction of their technological capital are:

- Learning environment

- Capture and transmission of knowledge

- Creation and development of knowledge

- Strategic alliances

- Intellectual and industrial property

Finally, the external factors of NTBFs, associated with science parks that influence in the construction of technological capability and the construction of their technological capital are:

- Support for internationalization

- Access to new financial instruments

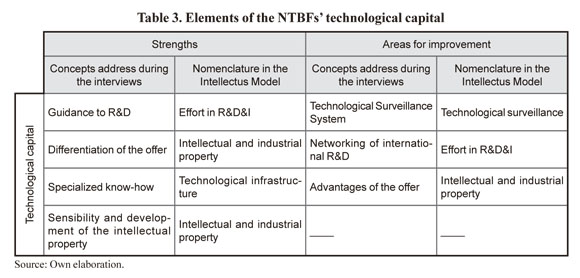

In particular, the sample results show that NTBFs have a strong technological capital to ensure growth and survival of these firms, since it refers to a set of intangibles associated with the development of activities and functions of the technical system of the firm, responsible both for the delivery of outputs (goods and services) with a set of specific attributes and the development of efficient production processes and for the progress on the knowledge base needed to develop future innovations in products and services. In this sense, and following the Intellectus Model, Table 3 shows the elements of NTBFs' technological capital classified in strengths and areas for improvement and related with: effort in R&D&I, technological infrastructure, combination of knowledge, methods and techniques, and intellectual and industrial property and technological surveillance.

The data analysis allows us to ensure that only those NTBFs able to efficiently manage their technological knowledge may alter their resource base and routines based on the strategic requirements of their environment.

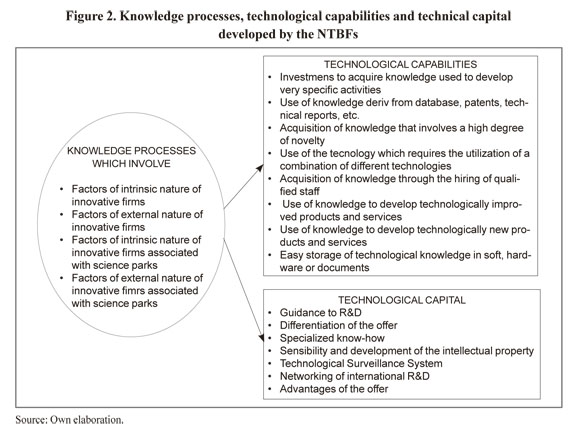

To sum up, the analysis shows the data corroborates the research issue which assert that when innovative firms develop their technological capability through of the mobilization of resources techno-science for the improvement or creation of new products and innovative production processes successfully, simultaneously, they are also constructing the elements of their technological capital. Figure 2 summarises the findings showing the knowledge process which contribute simultaneously to the construction and development of technological capability and technological capital and the technological capability and the technological capital created and developed.

Therefore, the congruence between the technological capability and intellectual capital development promotes the adaptability of NTBFs to the environment and the absorption of information and generation of useful knowledge by carrying out actions that impact the outcome of the NTBF such as profitability, sales or profit growth and productivity at work.

In this way, capitalizing on the results associated with the intangibles in economic terms, leads us to use multiple indicators of performance so as not to limit the possible derivations without thereby diminishing its value.

Also, technological capabilities play an important role because, through its dynamic function, they are responsible for a support activity, and give the firm appropriate resources and routines, needed to create value both directly in primary activities and indirectly, ensuring the quality, reliability, profitability and competitiveness of technological knowledge and support activities, whose outcome can serve to improve the knowledge base and the relationship between the firm and its customers, the quality of its products and services, but also the level of employee satisfaction, among others. All of this, through the processes of acquisition, development and dissemination of knowledge to generate competitive advantage and create value for the firm.

5. Conclusions and implications

In this paper we have studied the relationship between the technological capability and the intellectual capital in innovation firms. After a review of the literature about these two concepts, we have proposed that there is a relationship between the social processes of interaction to create and develop the intellectual capital and the ones focus on creating and developing the technological capabilities. These processes are social which involve the accumulation of knowledge within the firm, the assimilation of external knowledge, the individual technology, the organizational technology, the behaviors and skills of individuals and organizational skills and behaviors. The results are technological capabilities and technological capital which are keys for getting competitive sustainable advantages. From the Resource-based view strategic approach, the Dynamics capabilities approach and the Knowledge-based theory, we cannot avoid emphasizing the importance of knowledge for firms and countries to find the way back to growth hence the importance of studying its processes and results.

We have conducted a multiple-case study to analyze the relationship between the construction and development of technological capability and technological capital in 35 new technology-based firms created at the Madrid Science Park and the Leganés Science Park that are innovative firms. To provide the explanation of the research issue, we have needed understand the knowledge processes developed in these 35 firms, processes they use to construct their technological capability and their technological capital as well. After analyzing theoretically the technological capital in the intellectus model, as a model of measurement of intellectual capital, and the main approaches in the field of the technological capability, we have concluded that the more adequate approach to develop our research was the Intellectual Capital and the Resource-based view, Dynamics capabilities and Knowledge-based Theory. We have selected a case study methodology and we have used as primary data collection instrument semi-structured interviews, and as secondary data collection instruments observation and secondary resources.

The objective of the interviews was understood how the NTBFs construct their technological capability to answer the question "How do innovate?" Doing this we have found (figure 2): (1) the knowledge process which contribute simultaneously to the construction and development of the technological capability and the technological capital; (2) the technology capabilities develop in each firm; (3) the variables of the technological capital that were also constructed simultaneously that the technological capability. Moreover, we have also found the global aspects of the NTBFs and their results of these aspects which influence the development of the technological capabilities (table 2). These findings allow us to conclude that during the processes of construction of technological capability the 35 new technology-based firms of the study also constructed their technological capital. Following intellectus model, we have identified the elements of technological capital and the strengths and areas of improvement in these firms (table 3): effort in R&D&I; technological infrastructure; intellectual and industrial property; technological surveillance.

Therefore, in the 35 NTBFs analyzed the data corroborates the research issue, that is, in these firms there is a relationship between the process of construction of the technological capability and the intellectual capital. As it was mentioned in the theoretical background, they are small and micro innovative firms with a high proportion of employees and researchers qualified who develop social processes of knowledge in order to develop the best way to explore and exploit an invention and technological innovation through working in group, exchanging and sharing knowledge between all the members through conversations, infrastructure of information and communication technologies and infrastructure of production technologies.

The field of technological capability has already studied how this concept is a key element in the processes of strategic change and in situations of external context changes. However, past studies have not explored the relations between technological capability and technological capital in new organizations. This paper analyzed these relations by making a theoretical proposal and testing empirically in the context of 35 NTBFs created at the Madrid Science Park and the Leganés Science Park.

As it was mention in the Introduction, the contribution of our analysis is both theoretical and practical. On one hand, from a theoretical point of view, we have proposed: (1) a definition of Technological Capability; (2) a classification of Technological Capabilities; (3) and a theoretical relationship between Technological Capabilities and Intellectual Capital, specifically the Technological Capital. Furthermore, we have treated two outstanding concepts in organizational literature that have hardly been investigated empirically together which are: Technological Capabilities and Intellectual Capital. On the other hand, from a practical point of view, the findings of our empirical analysis will help innovation firms' members, and stakeholders in general (science parks, investors, etc.), to make suitable strategic and tactic decisions in order to get sustainable competitive advantages and, therefore, success in a quickly changeable environment by managing: (1) the global aspects of the NTBFs that have some influence in the Technological Capabilities; (2) the knowledge processes which construct and develop Technological Capability and Technological Capital; (3) and the specific Technological Capabilities and elements of Technological Capital constructed and developed.

6. Limitations and future research

As every empirical research our study is not free of limitations. These limitations could serve as guidelines for future research in the field of technological capability and its relations with the intellectual capital, therefore, we want to address them through alternative analysis in future researches:

- Generalizations: We have tested the research issue in 35 NTBFs created at the Madrid Science Park and Leganés Science Park so the findings of the multiple-case study cannot be generalized. However, these findings can serve as a starting point for future empirical work in order to make generalizations in the context of NTBFs at the Madrid Science Park and the Leganés Science Park.

- Resources and capacities of the firm: In the section Theoretical relationship between technological capital and technological capability, we have made a literature review to support this relation concluding that it emerges from the knowledge processes. Accordingly, we have applied a case study methodology to identify these processes and identify the technological capital and the technological capabilities they develop. However, it would be very interesting to go deep in these processes and explain, both theoretically and empirically, from the resource based view of the firm, the dynamic capabilities and the absorptive capacity perspectives: (1) how these processes, when they are accumulated and levered together, lead to the emergence of technological capabilities and technological capital; (2) their characteristics; and (3) their potential to strengthen the resources base and capabilities of the firms which are key to get a competitive advantage.

- Findings transferability: The grounded propositions presented about technological capital and technological capability might be applicable in NTBFs of other sciences parks different and even in other kind of new organizations different from NTBFs.

- Firm success: We have focused our efforts in studying the relationship between the construction of technological capability and the technological capital of 35 NTBFs. However, we have not analyzed the relation of these concepts to the success of these firms.

References

Acosta, J. C. (2009). Ba: Espacios de conocimiento. Contexto para el desarrollo de capacidades tecnológicas. Boletín Intellectus, 15, 12-18. [ Links ]

Acosta, J. C. (2010). Creación y desarrollo de capacidades tecnológicas: Un modelo de análisis basado en el enfoque de conocimiento. Madrid: Universidad Autónoma de Madrid. [ Links ]

Acosta-Prado, J. C. and Longo-Somoza, M. (2013). Sensemaking processes of organizational identity and Technological Capabilities: an empirical study in new technology-based firms. Innovar Journal, 23 (49), 115-130. [ Links ]

Acosta-Prado, J. C., Longo-Somoza, M. y Fischer, A. L. (2013). Capacidades dinámicas y gestión del conocimiento en nuevas empresas de base tecnológica. Cuadernos de Administración, 26 (47), 35-62. [ Links ]

Amit, R. and Schoemaker, P. (1993). Strategic asset and organizational rent. Strategic Management Journal, 14, 33-46. [ Links ]

Ansoff, H. (1965). Corporate Strategy. McGraw-Hill. Nueva York. [ Links ]

Aragón-Correa, J. A., García-Morales, V. J. y Hurtado-Torres, N. E. (2005). Un modelo explicativo de las estrategias medioambientales avanzadas para pequeñas y medianas empresas y su influencia en los resultados. Cuadernos de Economía y Dirección de la Empresa, 25, 29-52. [ Links ]

Argyris, C. and Schõn, D. (1978). Organizational learning: A theory of action perspective. Reading, M. A.: Addison Wesley. [ Links ]

Balconi, M. (2002). Tacitness, codification of technological knowledge, and the organisation of industry. Research Policy, 31, 357-379. [ Links ]

Barney, J. B. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal ofManagement, 17, 99-120. [ Links ]

Benavides, C. A. (1998). Tecnología, innovación y empresa. Madrid: Pirámide. [ Links ]

Bollinger, A. S. and Smith, R. D. (2001). Managing organizational knowledge as a strategic asset. Journal of Knowledge Management, 5 (1), 8-18. [ Links ]

Bontis, N., Crossan, N. and Hulland, J. (2002). Managing and Organizational Learning System by Aligning Stocks and Flows. Journal of Management Studies, 39, 437-469. [ Links ]

Boulton, R., Libert, B. and Samak, S. (2000). Cracking the Value Code. How Successful Businesses are Creating Wealth in the New Economy, NY: Harper Collins. [ Links ]

Bueno, E. (2002). Dirección estratégica basada en conocimiento: Teoría y práctica de la nueva perspectiva. En Nuevas claves para la Dirección Estratégica de la Empresa (pp. 91-116). Barcelona: Ariel. [ Links ]

Bueno, E. (2005). Fundamentos epistemológicos de Dirección del Conocimiento Organizativo: desarrollo, medición y gestión de intangibles en las organizaciones. Economía Industrial, 357, 1-14. [ Links ]

Bueno, E. (2013). El capital intelectual como sistema generador de emprendimiento e innovación, Economía Industrial, 388, 15-22. [ Links ]

Bueno, E. and CIC (2002). Intellectus model. Model for the measurement and management of Intellectual Capital, Documento Intellectus, 5, Madrid, CIC-IADE, UAM. [ Links ]

Bukh, N. (2003). The relevance of intellectual capital disclosure: a paradox? Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 16 (1), 49-56. [ Links ]

Butchart, R. (1987). A new UK definition of high technology industries. Economy Trends, 400 (febr.), 82-88. [ Links ]

Carmeli, A. and Azeroual, B. (2009). How relational capital and knowledge combination capability enhance the performance of work units in a high technology, International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 30 (8), 853-878. [ Links ]

Cassiman, B. and Veugelers, R. (2002). R & D cooperation and spillovers: Some empirical evidence from Belgium. American Economic Review, 92 (4), 1169-1184. [ Links ]

Cohen, W. and Lenvinthal, D. (1990). Absorptive capacity: A new perspective on learning and innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35, 128-152. [ Links ]

Cohen, W., Goto, A., Nagata, A., Nelson, R. and Walsh, J. (2002). R&D spillovers, patents and the incentives to innovate in Japan and the Unites States. Research Policy, 31 (8/9), 1349-1367. [ Links ]

Cohen, W. and Walsh, J. (2000J. R&D spillovers, appropiability and R&D intensity: A survey based approach. Mimeo, Carnegie Mellon University. [ Links ]

Coleman, J. (1988). Social Capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology, 94 (supplement), 95-120. [ Links ]

Conner, R. and Prahalad, K. (1996). A resource- based theory of the firm: Knowledge versus opportunism, Organization Science, 7 (5), 477-501. [ Links ]

Cook, J. and Brown, J. S. (1999). Bridging epistemologies: The generative dance between organizational knowledge and organizational knowing. Organization Science, 10 (4), 381-400. [ Links ]

Cool, K., Costa, L. and Dierickx, I. (2002). Constructing competitive advantage. In Handbook of Strategy andManagement (pp. 55-71). London: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Dawson, R. (2000). Knowledge capabilities as the focus of organisational development and strategy, Journal of Knowledge Management, 4 (4), 320-327. [ Links ]

DeCarolis, D. M. (2003). Competences and imitability in the pharmaceutical industry: An analysis of their relationship with firm performance, Journal of Management, 29, 27-50. [ Links ]

DeCarolis, D. M. and Deeds, D. L. (1999). The impact of stocks and flows of organizational knowledge on firm performance: An empirical investigation of the biotechnology industry. Strategic Management Journal, 20, 953-968. [ Links ]

De Geus, A. (1997). The living company. London: Nicholas Brealey. [ Links ]

Douglas, T. J. and Ryman, J. A. (2003). Understanding competitive advantage in the general hospital industry: Evaluating strategic competencies. Strategic Management Journal, 24 (4), 333-347. [ Links ]

Drucker, P. (2001). The Essential Drucker. New York: Harper Business. [ Links ]

Edvinsson, L. and Malone, M. S. (1997). Intellectual capital: Realizing your company's true value by finding its hidden brainpower. New York: HarperCollins Publishers. [ Links ]

Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review, 14, 532-550. [ Links ]

Eisenhardt, K. and Martín, J. (2000). Dynamic capabilities: The evolution of resources in dynamic markets. Strategic Management Journal, 21, 1105-1121. [ Links ]

Escorsa, P. and Maspons, R. (2001). De la vigilancia tecnológica a la inteligencia competitiva. Madrid: Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

Figuiredo, P. N. (2002). Does technological learning pay off? Inter-firm differences in technological capability-accumulation paths and operational performance improvement. Research Policy, 31, 73-94. [ Links ]

Friedman, A. (1994). The information technology field: Using fields and paradigms for analyzing technological change. Human Relations, 47, 367-392. [ Links ]

García, F. and Navas, J. E. (2007). Las capacidades tecnológicas y los resultados empresariales: un estudio empírico en el sector biotecnológico español. Cuadernos de Economía y Dirección de la Empresa, 32, 177-210. [ Links ]

Grant, R. M. (1991). The resource-based theory of competitive advantages: Implications for strategy formulation. California Management Review, 33 (3), 114-135. [ Links ]

Grant, R. M. (1996). Prospering in dynamically-competitive environments: organizational capability as knowledge integration. Organization Science, 7, 375-387. [ Links ]

Hall, R. (1992). The strategic analysis of intangible resources. Strategic Management Journal, 13, 135-144. [ Links ]

Hamel, G. and Prahalad, C. (1993). Strategic as Stretch a Leverage. Harvard Business Review, March-April, 75-84. [ Links ]

Hayek, F. A. (1945). The use of knowledge in society. The American Economic Review, 35 (4), 519-530. [ Links ]

Hill, C. and Jones, G. (2010). Strategic Management: An integrated approach. Mason: South Western Cengage Learning. [ Links ]

Johanson, U., Martensson, M. and Skoog, M. (2001). Measuring to understand intangible performance drivers. European Accounting Review, 10 (3), 407-437. [ Links ]

Kaufmann, L. and Schneider, Y. (2004). Intangibles: A synthesis of current research. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 5 (3), 366-388. [ Links ]

Kogut, B. and Zander, U. (1992). Knowledge of the firm, combinative capabilities, and the replication of technology. Organization Science, 3 (3) , 383-397. [ Links ]

Kogut, B. and Zander, U. (1996). What firms do? Coordination, identity, and learning. Organization Science, 7 (5), 502-523. [ Links ]

Kristandl, G. and Bontis, N. (2007). Constructing a definition for intangibles using the resource based view of the firm. Management Decision, 45 (9), 1510-1524. [ Links ]

Leonard-Barton, D. (1993). La fábrica como laboratorio de aprendizaje. Harvard Deusto Business Review, 58, 46-61. [ Links ]

Lev, B. (2001). Intangibles management, measurement and reporting. Washington D.C.: The Brookings Institution. [ Links ]

Levinthal, D. A. and March, J. G. (1993). The myopia of learning. Strategic Management Journal, 14, 95-112. [ Links ]

Little, A. D. (1977). New technology-basedfirms in the United Kingdom and the Federal Republic of Germany. London: Wilton House. [ Links ]

López, N., Montes. J., Váquez, C. y Prieto, J. (2004). Innovación y competitividad: implicaciones para la gestión de la innovación. Revista Madrid, julio, 24. [ Links ]

Low, J. (2000). The value creation index. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 1 (3), 252-262. [ Links ]

March, J. G. (1991). Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organization Science, 2, 71-87. [ Links ]

McClintock, C., Brannon, D. and Maynard M. (1979). Applying the Logia of Simple Surveys to Qualitative Case Studies: The Case Cluster Method. Administrative Science Quarterly, 24 (4) , 612-629. [ Links ]

McElroy, M. W. (2001). Social innovation capital. Draft, Macroinnovation Associates, Vermont: Windsor. [ Links ]

McGrath, R., MacMillan, I. and Venkataraman, S. (1995). Defining and developing competence: A strategic process paradigm. Strategic Management Journal, 16, 251-275. [ Links ]

Meso, P. and Smith, R. (2000). A resource-based view of organizational knowledge management systems. Journal of Knowledge Management, 4, 224-234. [ Links ]

Miles, M. and Huberman, A. (1984). Analyzing qualitative data: A source book for new methods. Beverly Hill, CA: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Nahapiet, J. and Ghoshal, S. (1998). Social capital, intellectual capital and the organizational advantage. Academy of Management Review, 23, 242-266. [ Links ]

Nelson, R. and Winter, S. (1982). An Evolutionary Theory of Economic Change. Cambridge: Belknap Press. [ Links ]

Nelson, R. (1991). Why do firm differ and how does it matter? Strategic Management Journal, 12, 61-74. [ Links ]

Nicholls-Nixon, C. and Woo, C. (2003). Technology sourcing and the output of established firms in a regime of encompassing technological change. Strategic Management Journal, 24, 251-266. [ Links ]

Nonaka, I. (1991). The knowledge-creating company. Harvard Business Review, 69 (6), 96-104. [ Links ]

Nonaka, I. (1994). A dynamic theory of organizational knowledge creation. Organization Science, 5, 14-37. [ Links ]

Nonaka, I. and Takeuchi, H. (1995). The knowledge creating company. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Ordóñez, P. (2003). Intellectual capital reporting in Spain: A comparative review. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 4 (1) 61-81. [ Links ]

Penrose, E. (1959). The theory of the growth of the firm. Oxford: Basil Black-Well. [ Links ]

Pérez-López, S. and Alegre, J. (2012). Information technology competency, knowledge processes and firm performance. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 112 (4), 644-662. [ Links ]

Peteraf, M. (1993). The cornerstone of competitive advantage: A resource-based view. Strategic Management Journal, 14, 179-191. [ Links ]

Polanyi, M. (1962). Personal knowledge. Towards a post-critical philosophy. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. [ Links ]

Porter, M. (1980). Competitive strategy. Techniques for analysing industries and competitor. New York: Free Press. [ Links ]

Prahalad, C. and Hamel, G. (1990). The core competencies of the corporation. Harvard Business Review, May-June, 79-91. [ Links ]

Quinn, J. (1992). Intelligence Entreprise. Free Press. [ Links ]

Rogers, D. (1996). The challenge of fifth generation R&D. Research Technology Management, 39 (4). [ Links ]

Roos, J., Roos, G., Edvinsson, L. and Dragonetti, N. (1997). Intellectual Capital. Navigating in the new business landscape. London: MacMi-llan Press. [ Links ]

Ruiz-Jiménez, J. and Fuentes-Fuentes, M. (2013). Innovación y desempeño empresarial. Efectos de la capacidad de combinación del conocimiento en Pymes de base tecnológica. Economía Industrial, 388, 59-66. [ Links ]

Sánchez, R. and Mahoney, J. (1996). Modularity flexibility, and knowledge management in product and organization design. Strategic Management Journal, 17, 63-76. [ Links ]

Schumpeter, J. A. (1939). Business Cycles. McGraw-Hill, New York. [ Links ]

Selznick, P. (1957). Leadership in administration: A social interpretation. New York: Harper & Row. [ Links ]

Spender, J. (1996). Making knowledge the basic of a dynamic theory of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 17, 45-62. [ Links ]

Spender, J. and Grant, R. (1996). Knowledge and the firm: Overview. Strategic Management Journal, 17, 5-9. [ Links ]

Stewart, T. (1997) Intellectual capital: The new wealth of organizations. New York: Nicholas Brealey Publishing. [ Links ]

Sveiby, K. (1997). The intangible monitor asset intellecttual. Journal of Human Resource Costing and Accounting, 2, 73-97. [ Links ]

Teece, D. (2000). Strategies for managing knowledge assets: The role of firm structure and industrial context. Long Range Planning, 33 (1), 35-54. [ Links ]

Teece, D. (2009). Dynamic capabilities & strategic management. organizing for innovation and growth. Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Teece, D., Pisano, G. and Shuen, A. (1997). Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 18, 509-533. [ Links ]

Trillo Holgado, M. and Fernández Esquinas, M. (2013). Caracterización de la innovación en spin offs de base tecnológica, Economía Industrial, 388, 67-78. [ Links ]

Von Krogh, G. and Roos, J. (1995). Conversation management. European Management Journal, 13 (4), 390-394. [ Links ]