Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Cuadernos de Administración

versión impresa ISSN 0120-3592

Cuad. Adm. vol.28 no.51 Bogotá jul./dic. 2015

https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.cao28-51.iecf

International expansion of Colombian firms: Understanding their emergence in foreign markets*

Expansión internacional de empresas colombianas: entendiendo su surgimiento en los mercados extranjeros

Expansão internacional de empresas colombianas: entendendoseu surgimiento nos mercados estrangeiros

Juan Velez-Ocampo**

Maria Alejandra Gonzalez-Perez***

*doi: 10.11144/Javeriana.cao28-51.iecf. This paper is the result of the "Multilatinas" research project financed by the Universidad EAFIT - Institución Universitaria Salazar y Herrera, from June of 2013 until June of 2015. We are very grateful for the helpful comments and insightful recommendations we received from the reviewers and editorial team of Cuadernos de Administración. We also wish to thank anonymous reviewers from the Iberoamerican Academy of Management Conference held in Sao Paulo, Brazil in 2013; and the Academy of International Business Latin American Chapter (AIB-LAT) Conferences in Puebla, Mexico 2013, and Medellín, Colombia 2014, for their valuable comments on earlier drafts of this paper. The paper was received on 02/06/2015 and was approved on 15/11/2015. Quotation suggestion: Velez-Ocampo, J., and Gonzalez-Perez, M. A. (2015). International expansion of Colombian firms: Understanding their emergence in foreign markets. Cuadernos de Administración, 28 (51), 189-215. http://dx.doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.cao28-51.iecf

**PhD student at Universidad EAFIT, Medellín, Colombia, and Associate Professor of International Business at Institución Universitaria Salazar y Herrera, Medellín, Colombia. E-mails: jvelezo@eafit.edu.co and juan.velez@iush.edu.co

***PhD. Full Professor of Management at Universidad EAFIT, Medellín, Colombia. E-mail: mgonza40@eafit.edu.co

Abstract

This paper aims to show that, although there is no evidence of a generalized pattern within the internationalization process of Colombian firms, there are common features in the majority of the observed firms: the election of exportations as the main entrance tool, the entrance to countries within a short geographical and psychological distance, and the development of local strategic advantages that eventually replicate abroad. A poll and a structured interview were used, including numerical and categorical variables, followed by a cross analysis ofcases. It was also found that internationalization decisions operate under an ad-hoc basis and rely heavily on the experience and intuition of top decision-makers at the company level.

Keywords: multilatinas, entry mode decisions, internationalization.

JEL Classification: F21, F23, F60

Resumen

En este estudio se muestra que aunque no hay evidencia de un patrón generalizarle en el proceso de internacionalización de compañías colombianas, hay algunos rasgos comunes en la mayoría de las empresas observadas: la elección de exportaciones como el modo de entrada inicial, el ingreso a países con baja distancia psicológica y geográfica, y el desarrollo de ventajas estratégicas locales que eventualmente se replican en el exterior. Se utilizaron una encuesta y una entrevista estructurada que incluyen variables numéricas y categóricas seguido de un análisis cruzado de casos. También se encontró que las decisiones de internacionalización operan bajo una base ad-hoc y dependen de la experiencia y la intuición de los altos ejecutivos de las empresas.

Palabras clave: multilatinas, decisiones de modo de entrada, internacionalización.

Clasificación JEL: F21, F23, F60

Resumo

Neste estudo, mostra-se que, embora nao haja evidéncia de um padrao generalizável no processo de internacionalização de companhias colombianas, há alguns traeos comuns na maioria das empresas observadas: a escolha de exportações como o modo de entrada inicial, o ingresso a países com baixa distancia psicológica e geográfica, e o desenvolvimento de vantagens estratégicas locais que eventualmente se reproduzem no exterior. Utilizaram-se uma enquete e uma entrevista estruturada que in-cluem variáveis numéricas e categóricas seguido de uma análise cruzada de casos. Também se constatou que as decisões de internacionalização operam sob uma base ad-hoc e dependem da experiéncia e da intuição dos altos executivos das empresas.

Palavras-chave: multilatinas, decisões de modo de entrada, internacionalização.

Classificação JEL: F21, F23, F60

Introduction

Since the 1990s, emerging and developing country multinationals (EMNEs and DMNEs) have played an important role in the global economy. In the last two decades, DMNEs have increased their market share and introduced new challenges to their counterparts from advanced economies in industries ranging from agriculture to services and technology (Bandeira-de-Mello, Fleury, Aveline and Gama, 2016; Gammeltoft, Pradhan and Goldstein, 2010; Narula, 2012; Ramamurti, 2012). The rise of EMNEs and DMNEs like Embraer and Vale from Brazil; Cemex and Bimbo from Mexico, Tata Group and Infosys from India, and the Chinese Huawei, Alibaba and Lenovo, among others, have increased the interest of both scholars and business managers on the determinants, trends and performance of EMNEs and DMNEs in international markets.

Recent International Business (IB) literature on the topic is divided in between a group of scholars that claim that EMNEs and DMNEs behave differently to other MNEs due to the specific contextual factors that these companies must face both locally and internationally. Therefore, there is a theoretical gap to be filled between the existing IB theories and the empirical evidence of these nascent enterprises that demands the creation of models and approaches to better understand this phenomenon (Guillén and García Canal, 2009; Ramamurti, 2009, 2012;). On the other hand, some scholars (Dunning, Kim and Park, 2008; Narula, 2012; Williamson and Zeng, 2009) argue that EMNEs and DMNEs behave differently as a response to the changes in the world economy rather than as a token of their country of origin. Most of the empirical studies dealing with this debate focus on EMNEs and DMNEs from a limited set of countries, especially China, India and Brazil (Ciravegna, Fitzgerald and Kundu, 2013; Fleury and Fleury, 2011; Gammeltoft etal., 2010; Matthews, 2006). Moreover, just a limited amount of studies (Bianchi, 2014; Gonzalez-Perez and Velez-Ocampo, 2014; Lopez, Kundu and Ciravegna, 2009; Losada-Otálora and Casanova, 2014) observe multinationals from Latin America (other than the Brazilian and Mexican ones) and Colombian MNEs, which boosts the relevance of this study on Colombian MNEs. Most of these authors have identified gaps in empirical evidences and existing theoretical understanding of the international expansion of firms from Latin America (multilatinas). This study was designed to provide a thorough account of the internationalization of a systematic sample of Colombian firms.

This paper contrasts preceding findings (Gonzalez-Perez and Velez-Ocampo, 2014) with empirical data from 41 Colombian firms with international operations, meaning both exports and FDI. Furthermore, this study makes three major contributions:

- It analyses the decisions of Colombian companies regarding not only international expansion, entry modes and market selection; as in Cuervo-Cazurra (2008), but also in respect of perceived obstacles in the internationalization of 41 companies. These finding are compared to the existing literature.

- It addresses some common traits in the internationalization of Colombian companies that have not been either observed or described in former studies on multilatinas.

- It contributes to the discussion on whether the DMNEs behave differently from traditional MNEs and young MNEs from industrialized countries and whether they require new theoretical models based on empirical grounded research or just an adaptation and extension of existing models.

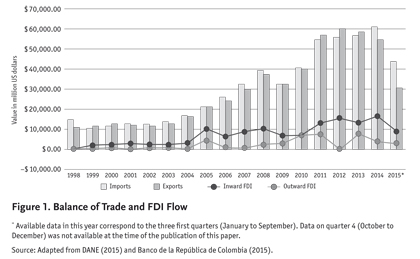

The internationalization of Colombian firms is a recent phenomenon and ex'sting literature on the topic is scarce. Besides, Colombia exports have belong mainly to the primary sector (mostly oil, mining, other extractive industries, coffee, flowers and bananas), with a high dependency on a few commercial partners. Nevertheless, in the last ten years, companies from developing and emerging markets, including Colombian MNEs, have entered into a phase of overseas expansion and their outward FDI have risen considerably faster than those from developed countries (Gammeltoft et at., 2010). Figure 1 displays the evolution of international trade in Colombia from 1998 to 2015, comparing both balance of trade and inward and outward FDI.

This paper is structured as follows. The next section presents a literature review on internationalization of Latin American firms followed by the research design and methodology used in this study, finally the findings, discussion, and conclusions are presented.

1. Literature Review

This section aims to provide theoretical lenses for the understanding of the international expansion of firms from Latin America, both multilatinas (multinational firms from the region), and internationally oriented firms.

Although MNEs have been studied for over sixty years (Hymer, 1960, 1968), the emergence of MNEs originated in developing and emerging markets is a recent phenomenon that needs understanding and rationalization. There is an ongoing discussion on whether or not the traditional theories on internationalization explain the international decisions of DMNEs and the need of either the adaptation of these theories or the implementation of new theoretical frameworks that contributes to better understanding of this phenomenon.

There is not an agreement upon what demarcates the international and multinational corporations. Luo and Tung (2007, p. 482) emphasize on FDI as key to recognize multinational firms (MNEs) as "international companies that are engage in outward FDI, where they exercise effective control and undertake value-adding activities in one or more foreign countries". Which excludes exporting firms (namely international firms) from their classification. Meanwhile, Cantwell etal. (2010), provide a broader definition of MNEs by stating that they consider these firms as "a coordinated system or network of value-creating activities". Furthermore, they argue that definition of MNE should not solely rely on foreign production facilities, but "activities may involve foreign sourcing of various intermediate inputs, including the sourcing of knowledge, as well as production, marketing and distribution activities" (ibid., p. 569). Which leaves room for considering international firms with international knowledge or marketing transfer as MNEs.

Although, DMNEs can't be seen as a homogenous group (Casanova, 2009; Dunning et al., 2008; Silva, Rocha and Carneiro, 2009; Ramamurti, 2009; Williamson and Zeng, 2009), different authors (Cuervo-Cazurra and Genc, 2008; Gammeltoft et al., 2010; Goldstein, 2009; Kiss, Danis and Cavusgil, 2002; Ramamurti and Singht, 2009; Rugman, 2009; Tan and Meyer, 2010) have identified that DMNEs have a competitive advantage in relation to MNEs from developed nations, and DMNEs have experience operating in contexts with underdeveloped institutions, political and economic instable countries, and in cost-sensitive markets. The development of EMNEs, and specifically multilatinas, can be explained by extending and modifying the existing theories and models rather than creating new ones (Cuervo-Cazurra, 2008; Dunning and Narula, 2004; Matthews, 2006).

Multinationals from Latin America, also known as multilatinas, have natural advantages when operating within their own region. Low psychic, geographical and institutional distance, similar consumer purchasing power, comparable levels of economic and social development, shared colonial history and therefore significant similar cultural elements define the shared characteristics of markets, and thus facilitate regional expansion (Aguiar et at., 2009; Castro Olaya et al., 2012; Cuervo-Cazurra and Genc, 2008; Cuervo-Cazurra, 2010; Cuervo-Cazurra, 2012; Gonzalez-Perez and Velez-Ocampo, 2014; Lessard and Lucea, 2009; Ramamurti and Singh, 2009; Vargas-Hernández and Reza Noruzi, 2010). Despite the relatively rapid internationalization process of multilatinas, Cuervo-Cazura and Genc (2008) draws attention to the fact that although, Latin American companies have a long exporting tradition, they have added value to their operations abroad only very recently. This recent internationalization has even favored countries outside the region. For countries such as Spain, the accelerated internationalization of multilatinas represents an advantage, as Spain could become the entry hub to Europe for these companies (Pla-Barber, Camps and Madhok, 2011; Santiso, 2014).

In the case of Brazilian multinationals, it has been found that seizing internationalization opportunities for these companies has been connected with organizational competences and managerial styles developed by firms while competing in the global industries at the local and international environments (Bandeira-de-Mello et at., 2016; Borini, Fleury and Fleury, 2009; Borini and Fleury, 2011; Fleury and Fleury, 2011). The amount of investment and number of foreign subsidiaries suggest that Brazilian firms focus their foreign activities on advanced markets (Arbix and Caseiro, 2011). Some studies have also found the importance of being embedded in business networks in the host country (Borini et at., 2009; Oliveira and Borini, 2012), and nurturing political connections in the home country (Bandeira-de-Mello et at., 2012) as both being key determinants for successful foreign market positioning (Bandeira-de-Mello et at., 2016). Furthermore, State industrial policies in support of the internationalization of firms and the accumulation of technological capability have been crucial drivers for the internationalization of Brazilian firms (Amann, 2009). Complementary, Silva et at. (2009) found that Brazilian firms have not followed a homogenous pattern of internationalization, but instead have adopted multiple strategies for investing and expanding abroad.

Sol and Kogan (2007) found than Chilean multilatinas are more profitable than Chilean firms with no foreign operations. The competitive advantage of Chilean multinationals was their business strategy to promote competitiveness during the economic liberalization. Bianchi (2014) identifies that the key resources and capabilities required by Chilean multinationals to perform well internationally are: family business groups, conglomerates, and network resources; partnerships and alliances resources; innovation orientation capability; and International managerial capability.

The Mexican outward FDI has been led by business groups and concentrated in Latin America (followed by North America) since the 1990s (Kunhardt and Gutiérrez-Haces, 2013; Sargent and Ghaddar, 2001), with the largest four Mexican MNEs (América Móvil, CEMEX, Grupo México and FEMSA) accounting for 81% of Mexico's total outward FDI (Kunhardt and Gutiérrez-Haces, 2013). According to Kunhardt and Gutiérrez-Haces (2013) the main driver for internationalization of Mexican multinationals has been maintaining and expanding their position in foreign markets.

According to Cuervo-Cazurra and Genc (2008), multilatinas have been induced to become MNEs after structural and country of origin reforms at the end of the 1980s and during the 1990s that have forced them to increase competitiveness at both domestic and international levels. Cuervo-Cazurra (2007, 2008) using Dunning (1977)'s eclectic paradigm as a framework of analysis, suggests that the internationalization of multilatinas has three possible sequences: marketing subsidiaries in all countries of operation, production subsidiaries in all those countries, or a combination of marketing subsidiaries in some countries, and production facilities in others. Ramsey, Magalhaes, Forteza, and Junior (2010) hold that multilatinas have focused their positioning in international markets by investing on strengthening locational advantages. Cuervo-Cazurra (2007) further argues that location advantages in the country of origin increase the likelihood of internationalization via the establishment of marketing subsidiaries abroad. When companies have either perceived advantages in the host country, or they encounter cross-country limitations on transferring products or services, it is foreseeable that they will begin their internationalization by setting up foreign production operations. Furthermore, although large firms in Latin America have a long exporting tradition, many of them have only recently become MNEs.

On the one hand, according to Casanova (2009) there are basically two factors that have influenced the internationalization of companies from Latin America: i) multilatinas looked for more stable economies abroad in order to overcome domestic instabilities; and ii) they also wanted to find more accessible financing in foreign markets. On the other hand for some other authors (Aybar and Ficici, 2009; Chunovsky and López, 2000; Dakessian and Felman, 2013; Fleury and Fleury, 2011) multilatinas' motivation for international expansion has been market and natural resources seeking, and acquisition has been the predominant foreign entry mode. This mode of international expansion offers relevant value-creation opportunities for firms. However, post-acquisition difficulties represent several risks such as "liability of foreignness" and "double-layered acculturation" (Barke-ma, Bell and Pennings, 1996). These risks deal with issues like the differences in national culture, business practices, institutional forces and customer preferences and prevent companies from achieving their strategic objectives (Aybar and Ficici, 2009).

According to the eclectic paradigm (Dunning, 1980), there are three reasons that trigger the internationalization of companies: search for market efficiencies, search for natural resources at reasonable prices and search for new markets; however, according to Casanova (2009), the main reason for multilatinas to internationalize is to increase their size through accessing new markets. Multilatinas share some specific characteristics that differentiate them from other western companies. They have a long-term planning, which does not prevent them from focusing on the present. Decision-making processes are decentralized, subsidiaries have the capacity to adapt to changing environments with ease and headquarters do not play a restrictive role; what is more, they have a strong background that relies on state-own enterprises and/or family businesses.

Even though the literature on multilatinas is scarce in general, most academic publications are focused on the case of Brazilian, Argentinian, Chilean and Mexcan firms. Literature on multilatinas from other Latin American countries is even more limited. Until now, there is only anecdotal evidence demonstrating that firms have mostly internationalized via strategic acquisitions and integration of acquired firms into their existing operations rather than via organic growth.

There are three main reasons for this study to analyze not only MNEs originated in Colombia, but also Colombian firms that engage in exports: first, according to Luo and Tung (2008), emerging markets companies share some special characteristics, for instance, they tend to leapfrog stages and trajectories in outward investment, frequently passing from export to production abroad. Besides, these firms accumulate benefits from inward FDI, imports, exports, alliances and joint ventures to eventually engage in FDI and become MNEs. Second, Latin American companies exhibit a very recent trend towards outward FDI, just after 2002 companies from this region enthusiastically get into FDI (Casanova, 2009) which added to the overall number of MNEs in the region, results in a limited set a companies to analyze. And third, compared with other Latin American countries, there are few Colombian MNEs. In the 2015 version of the AmericaEconomia multilatinas ranking (former versions of this ranking were used by Cuervo-Cazurra, 2008; and Bandeira-de-Mello et al., 2016) there are 9 Colombian within the top-100 companies, compared to 33 companies from Brazil, 25 from Mexico and 18 from Chile. This reduces the availability of analyzed cases and hinders a larger sample.

2. Research design and methodology

To analyze the internationalization of Colombian firms, 41 enterprises were studied. Authors chose to study Colombian enterprises because published papers on multilatinas are based in data mostly from Brazil and Mexico and in a lesser degree from Argentina and Chile; Colombia, the region's fastest-growing in 2013 and 2014, and third largest economy in Latin America according to The Economist (2014), has remained understudied and underrepresented. At the same time, the internationalization of Colombian firms has undergone a boost that is worth studying and comparing with existing literature.

The observed firms were selected as follows. Information of Colombian companies with either exports or FDI was searched on three different databases: 5000 Empresas Revista Dinero, Bacex and Legiscomex. Both international (or exporting companies) and multinationals (or companies with FDI) were included in this study due to the scarcity of multinationals among Colombian companies and the proclivity of international firms from emerging markets to rapidly engage in FDI as stated by Luo and Tung (2007). Authors discard all the Colombian subsidiaries of foreign companies as well as the state-owned firms, because the unit of analysis is the private locally-owned enterprises. Subsidiaries abroad were not sampled. Firms that do not evidence either exports or FDI since 2000 until 2013 were deleted because the purpose of the study is to analyze just both international and multinational enterprises, not local firms. To avoid double-counting, just one national subsidiary of each business group was considered. A total of 382 enterprises met the aforementioned characteristics and were shortlisted as eligible case studies. Researchers gathered profile data such as number of employees, financial statements, international presence, cash-flow statements, information on subsidiaries' performance, among others, and contacted electronically either CEOs or top executives responsible of internationalization in order to respond a survey. Within the first month of data collec-tionjust 11 executives positively responded the protocol, so researches decided to start a more aggressive data collection by calling and even visiting shortlisted companies. After approximately four months, 41 senior international business and general managers voluntarily collaborated with the study and provided primary data through multiple-choice and open-ended questions, representing 10.73% of the original sample of firms. Later, collaborators were contacted once again to apply a structured interview that 11 of them positively responded.

This exploratory research was partially designed based on both Johanson and Vahlne (1977)'s methodology and it was complemented with Cuervo-Cazurra (2011)'s international expansion strategy based on non-sequential internationalization. The methodology used in this study was inspired by the framework that Eisenhardt (1989) put forward. This process began with the definition of the research questions and the selection of the cases, and then with the design of the survey instruments and interview protocols, which in this case included both Likert scale queries and open-ended questions that after the data collection were classified following logical attributes in order to take advantage of emergent themes and unique case features. Both primary and secondary data were jointly displayed, tabulated and analyzed on a case-by-case basis. Then a cross-case analysis was performed in order to detect coincidences and differences in terms of internationalization strategies of the sampled firms; this analysis organized data by firm, country, motivations, industry, timing, entry strategy, internationalization spread and networks (Miles and Huberman, 1994). Then this analysis was compared to the existing literature about internationalization of DMNEs.

The emerging themes were operationalized into that were used for data processing. Based on a content analysis of the open-ended questions (both from surveys and interviews) binary variables were taken into consideration for this study. Variables were coded 1 if the responded made specific reference to the specific aspect, and 0 if otherwise. These variables were: (i) entry/current operation modes (exports, greenfield, licensing or franchising, joint ventures, mergers and acquisitions); (ii) drivers to internationalize (following competitors, managerial decision, risk reduction, market research results, contacts overseas, participation in international fairs, production surplus, and crisis in domestic markets); (iii) drivers for market selection (market size, increase competitiveness, possibilities for technological development, access to preferential taxes, low tariff barriers, good infrastructure, availability of raw materials, availability of labor, geographical proximity, and low psychic distance); (iv) perceived obstacles to internationalize (political risk, high taxes, high tariff barriers, low availability of raw materials, complicated means of payment, certifications -non tariff barriers-, and language differences). Later, a cross-case data analysis was conducted to investigate the initial observations further and see the evidence gathered through multiple lenses. The aim of this process was confirming or rejecting the existing theory.

The selection criteria imply some limitations for this study, especially regarding the generalization of the insights. First, as already mentioned, the analysis includes both international and multinational Colombian enterprises; a separate analysis of international or multinational enterprises may differ from the findings of this study. Second, as this study is cross sectional, subsequent international strategies, eventual market selection and subsequent entry modes were not studied. And third, the selection of companies of different sizes and sectors may tangle the generalizability of the findings, furthermore, single-sector analysis could lead to different findings. Considering these limitations, further research will be necessary to study just Colombian multinationals or specifically observe the differences internationalization patterns among sectors and sizes of Colombian firms.

3. Findings

3.1. Insights from studied case studies: Decisions to expand internationally by Colombian multilatinas

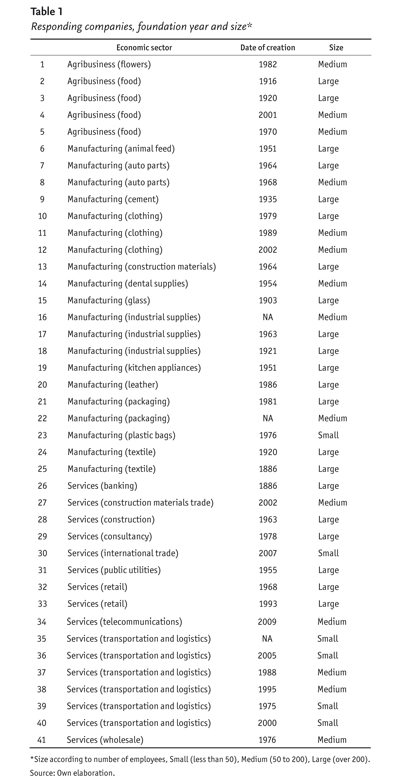

As table 1 displays, this study involved the collaboration of senior managers from 41 Colombian-owned firms. A pattern of learning-by-doing in the process of internationalization was observed. Based both on secondary data and data obtained by interviews, it could be concluded that this started at the beginning of the 1990s via exports with the establishment of the Colombian Government's macroeconomic policy based on market liberalization. Colombia's major firms (e.g. Bancolombia, ISA, Argos, Nutresa, EPM, Sura) have started to become more dominant in foreign markets since the year 2000 through portfolio investment and foreign acquisitions. Although there are variations in foreign country entry modes, as found in the case of Brazilian companies by Silva, Rocha and Carneiro (2009) and Fleury, Fleury and Reis (2010), in general, in the case of Colombian multilatinas, a tendency towards non-sequential establishment chains can be seen. This process tends to have the following sequence: exports, acquisition of foreign production facilities, and the establishment of marketing and sales facilities in host countries.

The study highlighted that 82% of the observed firms started their internationalization process by exporting; however, they eventually and slightly diversified their foreign operation and increased other operation modes such as licensing, franchising, joint ventures, mergers and acquisitions (M&As). When comparing this information with current entry/operation modes, exports reduce to 71% of the firms; meanwhile all the other modes increase their participation. Just 8% of the observed cases started their internationalization via greenfield investments, while 6% of the companies preferred licensing and franchising as their first entry mode. The least chosen entry mode corresponds to M&As, just 2% of the companies favored it as their initial entry mode, nevertheless, 11% of the observed companies eventually favor this entry mode.

The data indicated that Colombian firms tended to search for an increase in market size and to pursue asset diversification. This data might indicate that Colombian firms tend to search for an increased presence in foreign markets, and pursue diversification of assets and location as a risk management strategy. The latter can be considered as a proactive defensive behavior against potential specific (including home) market threats and international financial instability. The choice of the entry mode was also influenced by the economic sector in which the company operates; while manufacturing companies tend to first internationalize through exports, companies in the service sector (especially those in logistics and transportation) prefer to internationalize using greenfield, joint ventures, licensing or franchising.

Respondents were asked to rank different drivers to internationalize (e.g. production surplus, behavior towards competence, risk reduction, among others) driver for market selection (e.g. market size, availability of labor, geographical proximity, physic distance, among others) and obstacle to internationalize (e.g. taxes, certifications, language barrier, means of payment, among others) in a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 6, where 6 indicates very relevant and 1 non-relevant.

Respondents assessed internationalization drivers differently. The most common reasons to go international are managerial decisions (92.8% of the observed firms states this was a major driver to internationalize), defensive behavior towards competitors (86.8%), risk reduction (80.2%) and as a result of market research (80%). Traditional drivers as crisis in domestic market and production surplus, triggered internationalization in just 43.7% and 46.7% of the cases, respectively.

When selecting a market, the perceived potential market size plays a critical role (86.2% of the observed companies ranked it as a very relevant/relevant driver to internationalize), followed by possibilities of gaining competitiveness through increasing international experience (82.8%) and serving to more sophisticated markets with higher levels of technological development (79.3%). For Colombian companies, international trade taxes and tariffs are determinants when selecting a potential market. This is also reflected in the current trend of the country, which by 2014 has signed over 14 free trade agreements. The most relevant drivers for market selection of the observed companies (market size, competitiveness, technological development and taxes) are particularly significant when deciding to internationalize by exporting rather than by engaging in licensing, franchising or FDI.

Regarding perceived obstacles to internationalize, 79.3% of the managers called that both political risk and taxes are the most problematic issues they deal with when operating in foreign markets. Language is a main obstacle for 37.9%, sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) measures 44.8% and means of payment represented an obstacle for 55.2% of the firms. Concerning the perceived obstacles to internationalization for the sampled firms, international relations amongst countries are crucial. Recent diplomatic conflicts between Colombia and Venezuela affected the amount of international trade and inward FDI coming from both countries. This situation might have increased concerns regarding the importance of political stability when doing international business. Perhaps because the prime region for international expansion of Colombian multilatinas has been its own region, language barrier is not a decisive obstacle to internationalization.

The above information contributes to the existing literature on multilatinas, since they summarize the results regarding perceived drivers and obstacles for internationalization of the sampled firms in Colombia. They show the existence of a perception of the definitive role of a company's senior management on internationalization decisions, to the point that this is the most influential driver to internationalize, even above market research and risk reduction. The importance of the senior management's criteria is followed, as shown in the responses of the interviewed managers, by defensive behavior to adapt to competitor expansion. This is complemented with decisions of internationalization associated with possibilities of diversification in order to reduce risks, and with market research on the country targeted for expansion. Contacts overseas, sometimes reflecting the concentration of Colombian diaspora is another main driver to internationalize.

As these responses were collected in 2012 and 2013, the market liberalization that opened up the Colombian economy in the early 1990s was not considered an influential reason to expand; however, both Casanova (2009) and Cuervo-Cazurra (2007), agree that this transformation along with the restructuration that followed the Washington Consensus positively influenced the expansion of Latin American companies. Furthermore, these results broaden the conclusions and analysis of Gonzalez-Perez and Velez-Ocampo (2014) on Colombian multilatinas because in this case a larger sample and multiple research protocols were used to gather data.

3.2. Insights from in-depth interview with CEOs and senior managers

In the subsequent section, quotes from a selected group of respondents are going to be presented, in order to provide the reader with additional qualitative insights on the international expansion of Colombian multilatinas.

The following quote from a senior manager in a Colombian multilatina illustrates some of the relevant aspects taken into account for international investments.

Due to our lack of knowledge of international markets, the early part of the internationalization process of our company was highly dependent on strategy consultancy and investment banking firms, with the purpose of reducing risk. Then, overtime, we learnt about the importance of establishing strategic alliances and acquiring already established firms in host countries (Vice-President of a Colombian food multilatina).

The sentiment highlighted by this executive was reinforced in other interviews representing the views of other Colombian multilatinas. It was identified that at the beginning of the international consolidation period, the sampled companies tended to be dependent on international consultancy groups and the services of specialized investment firms. After a few years, however, the multilatinas were capable of internalizing this knowledge and thus strengthening the organizational capability of the firm in assessing potential foreign allies and acquisition targets, and for ensuring all due-diligences are in place. For these sampled companies, financial institutions are allies when internationalizing, nonetheless, managers recognized the importance of having organizational capacity for conscious decision-making regarding increasing commitments in a foreign country.

Banks are our allies for exploring and considering committing further resources in a foreign country. But, it is critical to make sure that our company has capacities for analyzing their recommendations, and make decisions based on our internal criteria (Vice-president at a Colombian energy and water multilatina).

Companies such as Nutresa (food) and Bancolombia (banking) have a common organizational internationalization strategy: acquiring assets and companies in foreign countries, which have a high level of local brand recognition and reputation with realistic possibilities of long-term engagement.

We have a mode of acquisition and a model of international intervention, and we are aware that every time we choose to acquire a company, we are choosing not to acquire other potentially good companies (Senior manager at a banking multilatina).

On the other hand, ISA's (energy generation) internationalization strategy has been to acquire companies with growth potential rather than already consolidated and fully developed companies.

Because of our sector (energy generation), we are looking for long-term financial pay-back. Because of this, our assessments are aimed at looking for companies located in countries with high levels of social, political and institutional stability (Senior manager at energy multilatina).

Although, as the previously cited quotations illustrate, each Colombian multinational has defined distinctive strategies for insertion and expansion in international markets, it is also observed that Colombian firms present a tendency to entry first to countries with low psychic and geographical distance, as is argued in the Uppsala internationalization model (Johanson and Vahlne, 1977). The data showed that for 51.7% of the observed companies geographic proximity and low psychic distance are highly desirable when investing abroad, and are very important criteria for market selection. However, there are also companies that have followed co-national pioneer companies into developed markets with high psychic and geographical distance, such as Japan. This could be explained by the historical tradition of trade relations between Colombia and the United States, and the high degree of recognition of country branding associated with the Colombian coffee industry, which is well positioned in Japan and the Netherlands. This is consistent with Ramsey et at. (2010), who stated that the propensity of multilatinas to succeed in their internationalization processes is associated with business models that include inter-firm collaboration via strategic alliances with companies already established in the host country, and with initiating outsourcing of production. Kotabe et at. (2000) indicate that in the case of Latin American companies, the most important motivation for a domestic company to have partnerships and collaborations with foreign companies is the possibility of having access to supplier connections and technology, followed by access to marketing expertise, the partner's financial resources (capital and credit line), direct access to foreign markets, and risk and cost reductions. This could also be explained by the business network theory (Johanson and Vahlne, 2009) in which companies forge business relationships with local businesses aiming to gain knowledge and connections to overcome the liability of foreignness in the host country.

In relation to the internationalization strategy, most companies have identified a combination of activities for successful international expansion and consolidation and for being immediately responsive to foreign markets needs and opportunities. For example, larger companies in the sample already have in place internal capacities for detecting international opportunities through strategic monitoring mechanisms, and have access to well-researched regional and local competitiveness studies.

In the case of the Colombian cement company Argos' internationalization in the Caribbean countries, that involved capturing the cement and concrete demand in those countries, which was previously supplied from Venezuelan cement firms. It was reported that market opportunities emerged in those countries due to nationalizations in Venezuela that negatively affected the competitiveness of the Venezuelan concrete and cement industry, which previously supplied the Caribbean market in this sector.

In the case of EPM (water and energy company), it chose to operate internationally once the domestic market was saturated, and additionally when it was facing anti-monopolist regulations in the water and hydroelectric generation industry. EPM has reported that it had a definitive regional competitive advantage in building hydropower stations, which it decided to internationalize.

The observed firms present a positive correspondence in terms of market selection and Colombian diaspora overseas; companies tend to establish in markets in which Colombian migration is abundant: Ecuador, Venezuela, Panama, Mexico, Central America, Spain and the United States. Managers rely on their own professional and personal network to enter markets overseas, which makes them overcome both the uncertainty of increasing the commitment abroad and perceived psychic distance. Once the company is present in a foreign market, the Colombian diaspora acts as its main potential market and provides business network support, which contributes to overcoming the liability of foreignness.

4. Discussion

As was previously set out, although it seems that there is no linear establishment chain, a sequence of internationalization events can be observed in the studied cases. The information presented also shows that Colombian companies first focus on consolidation in the domestic market. It is important to highlight that all of these companies have the largest market share in the Colombian national market in their own industries. Once they have gained significant competitive advantages consolidating their brand and have secured the largest share of their respective domestic markets, they commence an intense internationalization process. Markets within the Latin American region have similar market conditions and compatible legal systems. Setting up local production via acquiring already positioned companies in a foreign market makes political and economic sense because coordination and transportation costs decline (especially considering Colombian port limitations). Additionally, internationalization within the region represents a lower risk, taking advantage of existing trade agreements (such as the Pacific Alliance) and long-term commercial relationships.

When overlapping the internationalization patterns of Colombian firms, based on the described observations, it seems that managerial decision-making operates under an ad hoc basis, which strongly relies on managerial knowledge, organic growth, risk reduction via market diversification and availability of financial resources rather than on following the establishment chain or the foundations of Dunning (1980)'s eclectic paradigm. Even when compared with the internationalization of other emerging market firms, especially with firms from Brazil (Amann, 2009; Bandeira-de-Mello et at., 2012; Borini et at., 2009; Borini and Fleury, 2011; Casanova, 2009; Fleury and Fleury, 2009, 2011; Oliveira and Borini, 2012; Silva et al., 2009), Chile (Bianchi, 2014; Sol and Kogan, 2009) and Mexico (Kunhardt and Gutiérrez-Haces, 2013; Lessard and Lucea, 2009; Sargent and Ghaddar, 2001) Colombian companies seem to have differential drivers and capabilities for expansion. Traditional drivers for international expansion, like production surplus and presence in international fairs, do not seem to strongly influence Colombian companies as much as competitiveness of foreign markets, managerial knowledge and a defensive reaction towards competitor movements. On the other hand, Colombian firms perceive the following as major obstacles to internationalization: (i) political risk, (ii) taxes, and (iii) international certifications.

The limited (but increasing) amount of international business research focused on Latin American emerging markets has been made explicit by other authors (Cuervo-Cazurra and Genc, 2008; Fleury and Fleury, 2011). While in most studies dealing directly with the internationalization of emerging economies, multinationals have been centered on Asian companies (Buckley and Mirza, 1988; Chen and Chen, 1998; Collinson and Rugman, 2007; Goldstein, 2009; Kumar and Kim, 1984; Matthews, 2006; Pangarkar, 1998; Ramstetter, 1999; Yeung, 2000), or on other Latin American countries such as Brazil, Chile and Mexico. This paper offers a contribution to the internationalization literature of companies from a specific and under-researched Latin American country: Colombia.

On the one hand, the main findings of this paper suggest that the most relevant drivers for the internationalization of Colombian enterprises are the defensive behavior towards the international expansion of competitors, the managerial inclination for internationalization and the perceived risk reduction that the firm experience when entering foreign markets. The changes in local environment, government policies or incentives do not play such a significant role in the induction of local companies to become MNEs as found in previous studies on multilatinas.

On the other hand, the behavior of Colombian international and MNEs, their international decisions and patterns does not seem to need the development of new theoretical models but can be rather explained by adjusting existing theories and approaches.

As it was discussed in the findings section, no evidence was found in the sampled companies, which would allow for a generalization of either a sequential or a non-sequential international pattern in the case of Colombian firms. As the anecdotal quotes cited in previous sections illustrate, internationalization strategies are designed ad hoc. Nonetheless, there are clear inclinations to gravitate internationalization commitments based on competitive advantages developed in the domestic market, potential foreign market size, and deftness for doing business abroad. In the first stages of internationalization, there is a tendency to hire outsourced services of experienced firms for market research assistance in finding acquisition opportunities. This process tends to internalize in further stages, ascribable to organizational experiential learning and repetitive exposure to the process of acquisitions and establishing strategic alliances.

This study has some limitations that suggest further research. Firstly, although the observed firms share one main characteristic: being Colombian-owned international and MNEs, they belong to diverse fields, so this makes it more difficult to create a framework that explains DMNEs internationalization focusing on a specific industry. A second limitation is that this analysis does not address the internationalization patterns of multilatinas from countries other than Colombia; this leaves room for further research that might deal with the issue of analyzing advantages and disadvantages in the internationalization process of other multilatinas. A third limitation is that this study does not have a longitudinal approach; so this paper is not able to provide definitive information about cause-and-ef-fect relationship regarding the drivers for DMNEs to internationalize; instead, this study aims to provide an exploratory analysis of exports and outward foreign direct investment decisions of Colombian firms. Undoubtedly, future research is needed for theory testing and potentially for theory building.

5. Conclusions

Most of the observed firms favor direct and indirect exports over other entry modes. The ones that have obtained a stronger commitment abroad, for instance through M&As, have usually leapfrogged the establishment chain, mainly due, especially in the case of agribusiness and manufacturing firms (goods producers), managerial strengths and accumulated capital surplus that speed up the firm's international presence through direct foreign investment.

Findings of this study evidence that entry mode selection is influenced by the economic sector in which the company operates. For instance, in the case of service firms, the foreign entry mode tend to be either M&As, or greenfield investment, which is explained due the nature of industry that does not generally involve physical movement of services. Meanwhile, manufacturing companies opt to expand overseas through exports. Almost 80% of the collaborators of this study coincide in stating that political risks and taxes are the most relevant obstacles to internationalize, while language barriers and SPS measures result problematic in less than 45% of the cases.

Regarding specific type of industry, or date of creation of the firm, there were not found significant differences in terms of drivers to internationalize or market selection. Managerial decisions, defensive behavior towards competitors and risk reduction were relevant reasons to internationalize in over 80% of the studied firms. While crisis in domestic market and production surplus influenced the internationalization of less than 50% of the observed firms. Market selection is primarily influenced by market size, competitiveness and technological development of the host country; whereas issues like availability of labor and raw materials seem to be less significant.

Both local companies that are currently planning their internationalization and competitors of already international or multinational Colombian enterprises could benefit from the identified traits in this paper. The drivers, obstacles and criteria used in the market selection process might illuminate enterprises willing to embark on internationalization; which constitutes an advantage over the cases described in this paper, because this information was not available when they started their internationalization within the last two decades.

Although this research was designed to be an exploratory, and not theory testing or theory building perse, this paper supports Cuervo-Cazurra (2011) in the sense that the sampled Colombian multilatinas and international enterprises do not always follow a sequential internationalization model. It also supports Narula (2012) as our analysis suggests that current internationalization theories might partially explain the international expansion of infant EMNEs and DMNEs.

Regarding the debate on whether or not the understanding of the evolution of DMNEs need new theories or just the adaptation of the existing ones, the comparison of the findings with the IB theories and approaches suggests that so far an adaptation, extension and even combination of theories and models provide solid foundation for explaining, interpreting and analyzing the international expansion of multilatinas.

In conclusion, this paper offers scholars and business managers a description and analysis of learnt experiences from the internationalization Colombian firms. The study includes relevant information and direct quotations on the drivers for international expansion, market selection, perceived obstacles and entry modes that could eventually support managerial decisions of both local and foreign entrepreneurs. For international managers, this paper could be a resource for learning experiences from managers of Colombian firms and a useful source to come near the mindset of local entrepreneurs. It also provides guidelines for comparing Colombian firms with other emerging markets multinationals, and in the future determining if Colombian enterprises differ in their internationalization processes and strategies from other DMNEs. This study also observes the changes in terms of commitment and investment decisions that Colombian multinationals have made within the last two decades.

However, the debate on the need of new theories and approaches to understand DMNEs or the adaptation of the existing ones is still open and demands broader arguments and evidences to reach maturity and consensus. It is important to highlight that empirical grounded research that identifies and provides explanations on the ownership and country of origin specific advantages of DMNEs is still to be fully filled.

References

Aguiar, M.; Becerra, J.; De Juan, J.; Leone, E.; Nieponice, G.; Peña, I.; Pikman, M., and Ukon, M. (2009). The 2009 BCG Multilatinas: A Fresh Look at Latin America and How a New Breed of Competitors Are Reshaping the Business Landscape. Boston: The Boston Consulting Group. [ Links ]

Amann, E. (2009). Technology, public policy and the emergence of Brazilian multinationals. In: Brazil as economic superpower? Understanding Brazil's changing role in the global economy. Washington DC: The Brookings Institution. [ Links ]

AmericaEconomia (2015). Ranking Multilatinas 2015. AmericaEconomia. Retrieved on April 15th 2016 from http://rankings.americaeconomia.com/multilatinas-2015/ [ Links ]

Arbix, G., and Caseiro, L. (2011). Destination and strategy of Brazilian multinationals. Economics, Management and Financial Markets, 6 (1), 207-238. [ Links ]

Aybar, B., and Ficici, A. (2009). Cross-Border acquisitions and firm value: An analysis of emerging-market multinationals. Journal of International Business Studies, 40, 1317-1338. [ Links ]

Banco de la República de Colombia (2015). Flujos de inversión directa. Retrieved on December 11th From: http://www.banrep.gov.co/seriesestadisticas/see_s_externo.htm#flujos [ Links ]

Bandeira-de-Mello, R.; Arreola, M.F., and Marcon, R. (2012). The importance of nurturing political connections for emerging multinationals: Evidence from Brazil. International Business and Management, 28, 155-171. [ Links ]

Bandeira-de-Mello, R.; Fleury, M.T.L; Aveline, C.E.S., and Gama, M.A.B. (2016). Unpacking the ambidexterity implementation process in the internationalization of emerging market multinationals. Journal of Business Research, 16 (6), 2005-2017. [ Links ]

Barkema, H. G., Bell, H. J. H., and Pennings, J. M. (1996). Foreign entry, cultural barriers, and learning. Strategic Management Journal, 17 (2), 151-166. [ Links ]

Bianchi, C. (2014). Internationalisation of emerging market firms: an exploratory study of Chilean companies. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 9 (1), 54-78. [ Links ]

Borini, F. M., and Fleury, M.T.L (2011). Development of non-local competence in foreign subsidiaries of Brazilian multinationals. European Business Review, 23 (1), 106-119. [ Links ]

Borini, F. M.; Fleury, M.T.L. Leme and Fleury, A. (2009). Corporate competence in subsidiaries of Brazilian multinationals. Latin American Business Review, 10 (2-3), 161-185. [ Links ]

Buckley, P., and Casson, M. (2009). The internalisation theory of the multinational enterprise. A review of the progress of a research agenda after 30 years. Journal of International Business Studies, 40 (9), 1563-1580. [ Links ]

Buckley, P. J., and Mirza, H. (1988). The strategy of Pacific Asian multinationals. The Pacificreview, 1 (1), 50-62. [ Links ]

Casanova, L. (2009). Global Latinas: Latin America's Emerging Multinationals. Palgrave McMillan: New York. [ Links ]

Cantwell, J., Dunning, J. H., and Lundan, S. M. (2010). An evolutionary approach to understanding international business activity : The co-evolution of MNEs and the institutional environment. Journal of International Business Studies, 41 (4), 567-586. [ Links ]

Castro Olaya, J.; Castro Olaya, J., and Jaller, I. (2012). Internationalization patterns of multi-latinas. Ad-minister, 21, 33-54. [ Links ]

Chen, H., and Chen, T. J. (1998). Networks linkage and location choices in foreign direct investment. Journal of International Business Studies, 29 (3), 445-468. [ Links ]

Chunovsky, D., and López, A. (2000). A third wave of FDI from developing countries: Latin American TNSs in the 1990s. Transnational Corporations, 9 (2), 31-74. [ Links ]

Ciravegna, L.; Fitzgerald, R., and Kundu, S. (2013). Operating in emerging markets. New York: Financial Times Press. [ Links ]

Collinson, S., and Rugman, Alan M. (2007). The regional character of Asian multinational enterprises. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 24, 429-446. [ Links ]

Cuervo-Cazurra, A. (2007). Sequence of value-added activities in the multinationalization of developing country firms. Journal of International Management, 13 (3), 803-822. [ Links ]

Cuervo-Cazurra, A. (2008). The internationalization of developing country MNEs: The case of Multilatinas. Journal of International Management, 14 (2), 138-154. [ Links ]

Cuervo-Cazurra, A. (2010). Multilatinas. Universia Business Review, 25, 14-33. [ Links ]

Cuervo-Cazurra, A. (2011). Selecting the country in which to start internationalization: The non-sequential internationalization model. Journal of World Business, 46, 426-437. [ Links ]

Cuervo-Cazurra, A. (2012). Extending theory by analyzing developing country multinational companies: Solving the goldilocks debate. Global Strategy Journal, 2, 153-167. [ Links ]

Cuervo-Cazurra, A., and Genc, M. (2008). The multinalization of developing country MNES: The case of multilatinas. Journal of International Business Studies, 39, 957-979. [ Links ]

Dakessian, L.C., and Feldman, P.R. (2013). Multilatinas and value creation from cross-border acquisition: An event study approach. BAR-BrazilianAdministration Review, 10 (4), 462-489. [ Links ]

DANE. (2015). Comercio Exterior. Retrieved on December 11th from http://www.dane.gov.co/index.php?option=com_contentandwiew=articleandid=48andIterriid=56 [ Links ]

Dunning J. H., Kim C., and Park D. (2008). Old wine in new bottles: a comparison of emerging-market TNCs today and developed-country TNCs thirty years ago. In: The Rise of Transnational Corporations from Emerging Markets: Threat or Opportunity? Edward Elgar: Northampton, MA. [ Links ]

Dunning, J. H. (1977). Trade, location and economic activity and the MNE: A search for an eclectic approach. In: The International Allocation of Economic Activity. Macmillan: London. [ Links ]

Dunning, J. H. (1980). Explaining changing patterns of international production: In defense of the eclectic theory. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 41 (4), 269-295. [ Links ]

Dunning, J. H., and Narula, R. (2004). Relational assets: the new competitive advantage of MNEs and countries. Multinationals and Industrial Competitiveness: A New Agenda. Edward El-gar: Cheltenham and Northampton. [ Links ]

Economist (2014, August 2nd). Passing the baton. Available online at: http://www.economist.com/news/finance-and-economics/21610305-colombia-overtakes-peru-become-regions-fast-est-growing-big-economy-passing [ Links ]

Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Building theory from case study research. The Academy of Management Review, 14 (4), 532-550. [ Links ]

Fleury, A., and Fleury, M.T.L (2009). Brazilian multinationals: surfing the waves of internationalisation. In: Emerging multinationals in emerging markets (pp. 200-243). Cambridge University Press: Cambridge. [ Links ]

Fleury, A., and Fleury, M.T.L. (2011). Brazilian multinationals: Competences for Internationalization. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge. [ Links ]

Fleury, A.; Fleury, M.T.L., and Reis, G. G. (2010). The path is made by walking: The trajectory of Brazilian multinationals. Universia Business Review, 25, 34-55. [ Links ]

Gammeltoft, P.; Pradhan, J. P., and Goldstein, A. (2010). Emerging multinationals: home and host country determinants and outcomes. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 5 (3), 254-265. [ Links ]

Goldstein, A. (2009). Multinational companies from emerging economies composition, conceptualization and direction in the global economy. Indian Journal of Industrial Relations, 45 (1), 137-147. [ Links ]

Gonzalez-Perez, M. A., and Velez-Ocampo, J. F. (2014). Targeting one's own region: Internationalisation trends of Colombian multinational companies. European Business Review, 26 (6), 531-551. [ Links ]

Guillén, M. F., and García-Canal, E. (2009). The American model of the multinational firm and the "new" multinationals from emerging economies. The Academy of Management Perspectives, 23 (2), 23-35. [ Links ]

Hymer, S. (1960). The international operations of nationalfirms: A study of foreign direct investment. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [ Links ]

Hymer, S. (1968). La grande "corporation" multinationale: Analyse de certaines raisons qui poussent à l'intégration internationale des affaires. Revue Économique, 14 (6), 949-973. [ Links ]

Johanson, J., and Vahlne, J. E. (1977). The internationalization process of the firm-a model of knowledge development and increasing foreign market commitments. Journal of International Business Studies, 8 (1), 23-32. [ Links ]

Johanson, J., and Vahlne, J. E. (2009). The Uppsala internationalization process model revisited: From liability of foreignness to liability of outsidership. Journal of International Business Studies, 40, 1411-1431. [ Links ]

Kiss, A. N.; Danis, W. M., and Cavusgil, S. T. (2012). International entrepreneurship research in emerging economies: A critical review and research agenda. Journal of Business Venturing, 12 (3), 213-225. [ Links ]

Kotabe, M., Teegen, H., Aulakh, P., Coutinho de Arruda, M., Santillan, R., and Greene, W (2000). Strategic alliances in emerging Latin America: A view from Brazilian, Chilean, and Mexican Companies. Journal of World Business, 35, 114-132. [ Links ]

Kumar, K., and Kim, K. Y. (1984). The Korean manufacturing multinationals. Journal of International Business Studies, 15 (1), 45-61. [ Links ]

Kunhardt, J. B., and Gutiérrez-Haces, M. T. (2013). Updated features of large Mexican Multinationals, 2012. Vale Columbia Center on sustainable investment. [ Links ]

Lessard, D. R., and Lucea, R. (2009). Mexican multinationals: Insights from CEMEX. In: Emerging multinationals in emerging markets (pp. 280-312). Cambridge University Press: Cambridge. [ Links ]

Lopez, L. E., Kundu, S. K., and Ciravegna, L. (2009). Born global or born regional? Evidence from an exploratory study in the Costa Rican software industry. Journal of International Business Studies, 40 (7), 1228-1238. [ Links ]

Losada-Otálora, M., and Casanova, L. (2014). Internationalization of emerging multinationals: The Latin American case. European Business Review, 26 (6), 588 -602. [ Links ]

Luo, Y., and Tung, R. L. (2007). International expansion of emerging market enterprises: A springboard perspective. Journal of International Business Studies, 38 (4), 481-498. [ Links ]

Matthews, J. A. (2006). Dragon multinationals: New players in the 21st century globalization. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 23, 5-27. [ Links ]

Miles, M. B., and Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative Data Analysis. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Narula, R. (2012). Do we need different frameworks to explain infant MNEs from developing countries? Global Strategy Journal, 2 (3), 188-204. [ Links ]

Oliveira, M. M., and Borini, F. M. (2012). The role of subsidiaries from emerging economies: a survey involving the largest Brazilian multinationals. ThunderbirdInternational Business Review, 54 (3), 361-371. [ Links ]

Pangakar, N. (1998). The Asian multinational corporation: Strategies, performance and key challenges. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 15, 109-118. [ Links ]

Pla-Barber, J.; Camps, J., and Madhok, A. (2011) Springboard country and springboard subsidiary: a new perspective in the internationalization of European Multinationals in Latin America. Journal of Economic Geography, 12 (2), 519-538. [ Links ]

Ramamurti, R. (2009). What have we learned about emerging-market MNEs? In Emerging Multinationals in Emerging Markets (pp. 399-426). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Ramamurti, R. (2012). What is really different about emerging market multinationals? Global Strategy Journal, 2, 41-47. [ Links ]

Ramamurti, R., and Singh, J. V. (2009). Emerging multinationals in emerging markets. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Ramsey, J. R.; de Magalhães A. F.; Forteza, J. H., and Junior, J. F. (2010). International value creation: An alternative model for Latin American Multinationals. GCG: Revista de Globalización, Competitividadand Gobernabilidad, 4 (3), 62-83. [ Links ]

Ramstetter, E. (1999). Comparison of foreign multinationals and local firms in Asian manufacturing over time. Asian Economic Journal, 13 (2), 163-203. [ Links ]

Rugman, A. (2009). Theoretical aspects of MNEs from emerging economies. In: Emerging multinationals in emerging markets (pp. 3-22). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press: Cambridge. [ Links ]

Rugman, A. M., and Verbeke, A. (2004). A perspective on regional and global strategies of multinational enterprises. Journal of International Business Studies, 35 (1), 3-18. [ Links ]

Santiso, J. (2014). El auge de las multilatinas ¿Una oportunidad para España? Harvard Deusto Business Review, 240, 20-30. [ Links ]

Sargent, J., and Ghaddar, S. (2001). International success of business groups as an indicator of national competitiveness: The Mexican case. Latin American Business Review, 2 (34), 97-121. [ Links ]

Silva, J. F.; Rocha, A., and Carneiro, J. (2009). The international expansion of firms from emerging markets: Toward a typology of Brazilian MNEs. Latin American Business Review, 10 (2-3), 95-115. [ Links ]

Sol, P., and Kogan, J. (2007). Regional competitive advantage based on pioneering economic reforms: The case of Chilean FDI. Journal of International Business Studies, 38, 901-927. [ Links ]

Tan, D., and Meyer, K. E. (2010). Business groups' outward FDI: A managerial resources perspective. Journal of International Management, 16 (2), 154-164. [ Links ]

Vargas-Hernández, J.G., and Reza Noruzi, M. (2010). An exploration of the status of emerging multinational enterprises in Mexco. International Business and Management, 1 (1), 28-29. [ Links ]

Williamson, P., and Zeng, M. (2009). Chinese multinationals: emerging through new global gateways. In: Emerging Multinationals in Emerging Markets. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Yeung, H. W. (2000). The globalization of businessfirmsfrom emerging economies. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. [ Links ]