Introduction

Over the last two decades, there has been a growing interest in listening to children's voices in educational research. This has further been fuelled by the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UN, 1989) stating that governments and stakeholders must ensure ways of listening to children's voices in matters that affect their everyday life (Robinson, 2014), and by theoretical developments especially considering both sociological (James, 2007; James, Jenks and Prout, 1998; Qvortrup, Bardy, Sgritta y Wintersberger., 1994) and educational studies (Clark, 2007; Dockett, Ein-arsdottir and Perry, 2009; Pascal and Bertram, 2009; Stephenson 2009). This is further supported by international and national agendas urging the need to voice children's views (Christensen and James, 2008; Lewis, 2010; Thomson, 2008), and where children are seen as active agents in the construction of their own life. The latter view is very much in line with a postmodern perspective where children are seen as knowledgeable, strong, capable and experts on their own lives (Bruner, 1996; Clark and Moss, 2001; Dahlberg, Moss and Pence, 1999; Mayall, 2000). Moreover, Freeman (1998) highlights the need to take children and their views more seriously in light of the contemporary movement regarding children's rights in international agendas (Lewis 2010; Thomson, 2008). However, our literature review suggests that there is no study that analyses in a systematic way the most common methodological strategies researchers use to listen to children's voices in educational research. This seems to be an unfortunate gap especially in view of this growing interest.

Research with and for children rather than on children (Darbyshire MacDougall and Schiller, 2005; Mayall, 2000; O'Kane, 2000) has triggered an international debate about tensions pertaining to theoretical, ethical and methodological implications in this field. These tensions are well-documented in the international literature whereby it is questioned the extent to which theoretical, ethical and methodological issues are suitable when doing research with and for children (Clark, 2005; Dockett, Einarsdottir and Perry, 2009; Elden, 2013; Einarsdottir, 2007; Tangen, 2008). Ethical implications focus on issues related to the need to seek children's consent, consider children's context, the pertinence of data-collection methods used, ensuring confidentiality and child protection (Fraser, Lewis, Ding, Kellett and Robinson, et al., 2004; Rinaldi 2005; Tangen 2008). Theoretical implications are concerned with the analysis of epistemological assumptions (i.e., that from adults) and some theoretical approaches among which we can find subjectivism, empiricism, structuralism or postmodernism (See Tangen [2008] for a further description of these theories).

Moreover, epistemological-related issues also focus on analysing the way in which adults misuse or misrepresent children's voices (Mouritsen, 2002; Qvortrup, 1994; Thyssen, 2003) with an alleged aim of "...breaking new ground in research which children" (Schiller and Einarsdottir, 2009, p. 126). Child-adult relations of power in research are also of interest to scholars (Fargas-Malet, McSherry, Larkin Robinson, 2010; Gabb, 2010; Tangen, 2008). However, there is little literature (Clark, 2005; Einarsdottir, 2007; Fargas-Malet et al., 2010; Mortimer, 2004; Tangen, 2008; Pascal and Bertram, 2009) which actually focus on the analysis of the methodological aspects, specifically when listening to children's voices. This little body of literature, indeed, places at the core of the debate and thus analyse the advantages and limitations of a range of methodological strategies used to listening to children's voices, such as photography (Dockett and Perry, 2005), drawings (Leonard, 2007), interviews (Morrow, 2001), stimulus material or prompts (Clark, 2005), participatory techniques (Christensen and James, 2000), diaries (Cook-Cottone and Beck, 2007), observations (Mayall, 2000), focus groups (Wahle, Ponizovsky-Bergelson, Dayan, Erlichman & Roer-Strier, 2017) and questionnaires (Scott, 2000). Nevertheless and while we acknowledge that these efforts represent a great progress in terms of ascertaining the adequacy of such strategies, there is no study which systematically reviews the most commonly used methodological strategies in recent educational research with children under the age of 7, with a view to proposing future directions by using innovative approaches. Moreover, and considering the limited body of evidence regarding a systematic analysis in this respect, it is difficult to ascertain what the "gold standard" approach for listening to children's voices is. Our review of literature suggests that interviews (i.e., in combination with other child-led strategies such as drawings, pictures, photos, etc.) seem to be the most preferred strategy used to this end. However, their effectiveness has been constantly questioned mostly regarding adult-child power imbalances and how the information is interpreted and potentially biased by adults. The need to critically analyse the methodological strategies researchers use when working for and with children-especially when listening to their voices- is clear, and it is strongly emphasised in the literature (Barker and Weller, 2003; Fargas-Malet et al., 2010; Schiller and Einarsdottir, 2009; Sanders and Munford, 2005; Spyrou, 2011). Besides, the results of these studies highlight the need to take into account not only the context and characteristics of the participants, but also the adequacy of the strategies researchers use. This notion is further supported by Mortimer (2004) when she urges the need to come up with creative and flexible approaches when working with children and, more importantly, when listening to children's voices-but what is like, to listen to children's voices?

Defining the concept of "listening to children's voices" is not an easy task since listening is most of the times considered a passive process whereby the messenger delivers a "message" and the listener "listens" to the message-a quite passive process. In this study, however, we embrace the definition provided by Pascal and Bertram (2009), as we concur with the idea that listening to children is an "...active process of receiving, interpreting and responding to their communications" (p. 255) whereby meanings are exchanged (Clark, McQuail and Moss, 2003). We also consider Tangen's views (2008) as he suggests that the context this communication takes place in is of utmost importance to interpret and give meaning to the ideas exchanged, in which case, ".listening to children's voices is contextual and interactional" (p. 159) and should be seen as an ongoing and active process rather than a location (Komulainen, 2007). The way in which children's voices must be listened has been a controversial issue, which has questioned the strategies used to this end (Komulainen, 2007; Spyrou, 2011). Specifically, Spyrou (2011) and James (2007) strongly suggest that the research process undertaken to listen to children's voices must be thoroughly examined in order to tackling issues in terms of representation and interpretation of children's opinions, which is a view supported by other scholars (Mouritsen 2002; Qvortrup 1994; Thyssen 2003). Notwithstanding this, a more critical stance towards the children's voices field calls for the need not only to uncover aspects related to epistemological or ethical issues dealing with the way adults interpret children's beliefs (Elden, 2013; Rinaldi, 2005), but what media are used to listen to what they have to say. It is well documented that research to listen to children's voices copes with both ethical and theoretical considerations, but also with methodological challenges (Alderson and Morrow, 2004; Einarsdot-tir 2007; Greene and Hill 2005; Pascal and Bertram 2009). This suggests the need to conduct further studies aimed at analysing what methodological strategies allow researchers to truly listen to children's voices, rather than assessing cognitive abilities such as memorisation, verbal comprehension or phonological awareness. Interestingly, there seems to be a tendency among scholars to use the notions "listening to children" and "assessing children" interchangeably. Indeed, we must clarify that they are not the same. Children's apparent interests and needs are well-documented in the literature, nevertheless we need to question such evidence, given the fact that the information concerning this respect comes mainly from the views of adults-namely teachers, parents, and policymakers (Elden, 2012; James 2007). The limited evidence about the topic suggests that researchers tend to neglect-or at least minimise-the relevance of documenting and analysing what children have to say. While gathering information from adults may seem justifiable in terms of interested parties taking the lead in gathering empirical evidence and thus generating the most adequate policies for safeguarding children, it does not necessarily mean that children's voices cannot be listened to and/or even be included in safeguarding policies.

Worldwide literature on listening to children's voices clearly suggests that it is a fast-growing and ever-changing field which is aligned not only with recent developments in childhood studies, but also with the international agenda which sets a suggested guideline in terms of the challenges to be addressed in educational matters from a global perspective (Dodds, Donoghue and Roesch, 2016; Buckler and Creech, 2014). We are particularly concerned with the methodological strategies which researchers have used to listen to children's voices before and after the declaration of the new international agenda through the Sustainable Developmental Goals-SDG (UN, 2015) specifically considering the goal number four. This goal relates to the challenges to be addressed in the educational sphere, and to our knowledge, there is no recent systematic review which analyses the most widely used methodological strategies to effectively listen to children's voices. This review will help us infer how this agenda has shaped international researchers' views and interests in terms of the methodological strategies used in educational research to listen to the beliefs of children under the age of 7. This interest is further supported by the idea that the earlier we intervene, the better results we can obtain about children' views, interests and needs to better inform policy, research and practice in matters that affect children's lives (Farrington and Welsh, 2008; Karoly, Kilburn and Cannon, 2006; Karoly and Levaux, 1998). This is the reason why we focus this study on research published from 2015. We are aware that the peer-reviewed publication-related process might mean that studies published from that year may also reflect the researchers' agenda prior to the publication of the SDGS. Nevertheless, we firmly believe that this study will also be valuable to identify the tendencies in educational research concerned in children's voices through the transition from one agenda to another (Fukuda-Parr, 2016). We are mindful that a similar study may need to be conducted considering the Millennium Developmental Goals (MDGS). This would be useful to complement the findings of this study and, thus, enhance our knowledge and understanding of the most widely used methodological strategies to listen to what children have to say. We argue that educational research should give more importance to listening to children's voices, but above all, we, as researchers, must engage in a systematic analysis and subsequent identification of effective tools which have been used up to date. It is important to do so, as it will allow us to establish which ones are effective and which are not, what has been used and what has not, and how those strategies identified could be improved. This will lead to innovative proposals to effectively listen to children's voices. We argue that the strategies used by researchers should consider children as knowledgeable, active participants and experts on their own lives with rich information about pertaining issues affecting their everyday life. This is true as not only responding to children's needs, but also listening to their views, have been recognised as good practices in educational systems (Bae, 2004; Clark, McQuail and Moss, 2003; Rye, 2005). However, a systematic knowledge of the type of strategies through which researchers listen to children's voices currently is yet unknown. This study sought to analyse systematically current evidence in the literature regarding the type and nature of methodological strategies researchers use worldwide to listen to children's voices in educational research.

Methodology

A systematic review has been defined as "a scientific process governed by a set of explicit and demanding rules oriented towards demonstrating comprehensiveness, immunity from bias, and transparency and accountability of technique and execution" (Dixon-Woods 2011, p. 332). As a result, we decided to conduct our systematic review in line with the methodological approach recommended by the Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre (EPPI-Centre, 2007), to provide a robust evidence for identifying the most common methodological strategies used to listen to children's voices. Our review was guided by the following research question: What are the most common methodological strategies used in empirical studies in educational research that focus on "listening to children's voices"?

We ensured that our analysis was systematic by following the steps outlined by the EPPI-Centre (2007) and illustrated diagrammatically in Figure 1:

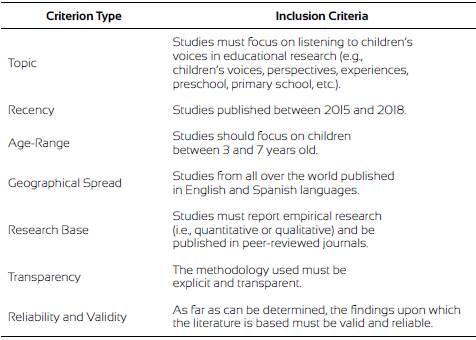

Scoping the review. We developed specific criteria for the inclusion of studies (Table 1).

Searching for studies. We identified the particular literature to be included in this review by using an agreed set of search terms: Child* AND voice/perspective/experiences AND nursery, kindergarten, preschool, primary school. We included the following databases: ERIC, EBSCO, BEI, SCIELO, ProQuest and Web of Science.

Screening studies. We ensured that the research question could be answered by screening each piece of literature against the inclusion criteria and by having specific rules as to the literature which must be included.

Describing and mapping. We created a grid to analyse the mechanisms through which the studies included listened to children's voices, considering the transparency of the methodology and the weight of evidence which allows to systematically describe the specific strategies used by researchers.

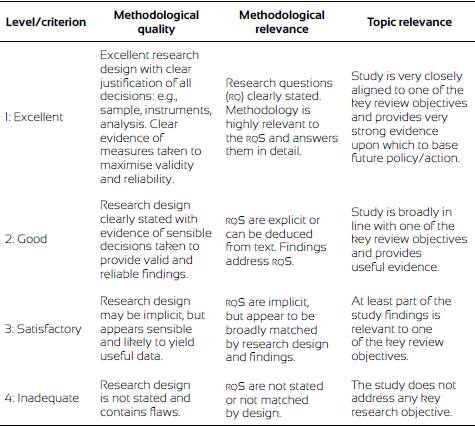

Quality and relevance appraisal. We evaluated each study in terms of the methodological quality, methodological relevance, topic relevance and overall weight of evidence following the criteria described in Table 2.

Synthetizing study findings. The mapping described in number 4 was used to bring together the results in a structured way that summarised the transparency of the methodology, strategies used and weight of evidence (WoE). Studies with high WoE were described as "strong evidence", while those with low WoE were described as "reasonable evidence".

Conclusions/Recommendations. Based on our findings, we made some recommendations to make evident and transparent the support we provided to each recommendation. We also commented on potential limitations in terms of generalisation of findings.

The research team comprised four researchers, which allowed us to triangulate information to enhance the quality of the analysis and verify the interpretation of data through all stages of the review process. The team started by establishing the inclusion/exclusion criteria to specify the literature to be included in this review to help us address the research question (see Table 1). Based on these criteria, we used a series of specific terms related to listening to children, in order to find studies in the above-mentioned databases. We focused our search on scientific articles published in peer-reviewed journals and retrieved a number of studies which we then screened jointly against the inclusion criteria. We outlined the mechanisms through which each study listened to children's voices, the transparency of the methodology used and the weight of evidence -elements which were relevant and related to our research question. These elements were used to create a grid which provided a systematic description of the particularities of each study to address our research question. Finally, based on the structured descriptions we came up with by using the grid, we brought together the results to analyse the evidence which helped us answer our research question. Throughout the process, a high level of agreement among the members of the team was reached, hence there was no need to look for any statistical figure regarding inter-rater reliability.

Results

Two hundred and ten empirical studies were considered to address our research question, but only 34 out of them met the inclusion criteria for this study, and contained empirical evidence relevant to methodologies used when listening to children's voices. All of the articles included were written in English. No articles written in Spanish language that met our criteria were found. The samples used in the studies reviewed ranged from one child to 721 children. The study topics which researchers mainly focused on, could be categorised in four main areas with topics related to social interaction and values (e.g., gender stereotypes, bullying), academic-matters (e.g., transition to kindergarten, preference of books), home (e.g., knowing the neighbourhood, cleaning up duties) and play-centred pedagogies (e.g., augmented reality, play-based learning). Most of the studies focused on topics related to the first area. Thirty-two studies used a qualitative approach while only two followed a mixed-methodology (Wang, 2015; White, 2016). However, the methods used with children in these studies were purely qualitative. The quantitative aspect of these studies was focused on teachers and parents.

The distribution per year of publication-ratio of the studies included is as follows: 2015, 20; 2016, 5; 2017, 7; and 2018, 2. Results from this analysis revealed that the greatest weight of evidence in the literature reviewed referred to the use of interviews as a common strategy to listen to children's voices, followed by reasonable evidence of group discussions/ focus groups and observations. There was some limited evidence regarding studies using hands-on activities where children played a more active role in gathering information from their environments. Notably, these studies implemented various hands-on activities which were not found to be common in the literature reviewed. Some of these activities implied children creating a mind-map (McEvilly, 2015), children completing a story told by an adult (White, 2016), the use of vignettes and scenarios to elicit children's views (Almqvist and Almqvist, 2015), children leading a housetour (Merewether, 2015), children walking around their community, and video-recording outdoors (Fleer and Li, 2016), and projective techniques by using the Pictorial Measure of School Stress and Wellbeing (PMSSW) interview (Harrison and Murray, 2005). Now, we will give a closer look at the evidence pertaining to the strategies identified.

Interviews

Evidence from our review strongly suggests that interviews are the preferred-or at least the most common-strategy to listen to children's voices. The most prevalent types of interviews found in our review were semi-structured (Fekonja-Peklaj and Marjanovic-Umek, 2015; Koller and San Juan, 2015; Northard et al., 2015; Reunamo et al., 2015; O'Rourke, O'Farrelly, Booth and Doyle, 2017; Wernet and Nurnberger-Haag, 2015; Wu, 2015), and only two studies used structured interviews (Correia and Aguiar, 2017; Kotaman and Tekin, 2017). It is interesting to note that while interviews were the main strategy to listen to children's voices, we found a great variation in their use with regards to conditions, circumstances and material used to elicit children's views. For instance, we found reasonable evidence that interviews were conducted with the help of pictures and images (Baird and Grace, 2017; Baker, Tisak and Tisak, 2016; Cheng Pui-Wah Reunamo, Cooper, Liu and Vong, 2015; Correia and Aguiar, 2017; Li, 2016; Penderi and Rekalidou, 2016), hypothetical situations (Cheng Pui-Wah et al., 2015; Reunamo et al., 2015), with photos children took (Adderley et al., 2015; McEvilly, 2015; Wahle et al., 2017; White, 2015), using dolls (Baird and Grace, 2017; Correia and Aguiar, 2017; Koller and San Juan, 2015; White, 2016), having children drawing while being interviewed (Fleer and Li, 2016) or by using children's drawings (Adderley et al., 2015; Katz and McLeigh, 2017; Leigh, 2015; Wahle et al., 2017). However, there was less emphasis in the use of the "draw and tell" method (Fluckiger, Dunn and Stinson, 2018; O'Rourke et al., 2017; Wahle et al., 2017; Wong, 2015), play-based interviews (Koller and San Juan, 2015), and interviews including a story-telling (Gunnestad, Morreaunet and Onyango, 2015). Interestingly, we found only one study which used an ecocultural interview approach (Baird and Grace, 2017) following the eco-cultural theory and more specifically the Ecocultural Family Interview (EFI) developed by Gallimore, Thomas, Kaufman and Bernheimer (1989). This theory is characterised by exploring activity settings in different domains of family life (i.e., domestic workload, support networks, friendship, family connectedness). Grace and Bowes (2009) adapted the EFI to be used with young children, leading to the Ecocultural Child Interview.

Group discussions/Focus groups

Reasonable evidence was found related to the use of focus groups and group discussions to listen to children's voices. We merged these two categories in this section following the principles of group discussions with children which are well documented in the literature and which aim at creating a secure, friendly and non-threatening environment for children to speak freely alongside their significant others, their peers (Barbour, 2008; Vaughn, Schumm and Sinagub, 1996). We also considered that one of the main differences we found between using focus groups-following the authors' definition-in few studies, such as those of Hammond, Hesterman and Knaus (2015) and Sandberg et al. (2017), and using group discussions in studies like those from Adderley et al. (2015), Green (2015) and Wahle et al. (2017), was the way in which the discussion was structured and facilitated. However, the main aim was the same-listening to what children had to say in a safe environment where they feltvalued and heard. It is noteworthy that a reasonable number of studies reviewed used these strategies, precisely, to create a secure environment for children with the purpose to reduce the adult-child power imbalances (Alderson, 2000; Gallagher, 2008), and thus, allow children to speak freely.

Similarly to what we found with the interviews, group discussions varied in terms of the organisation and material used by researchers to prompt children's narratives. We found that some researchers conducted group discussions while children were drawing and writing (Harwood and Copfer, 2015; Leigh, 2015; Wahle et al., 2017), while others used puppets (Almqvist and Almqvist, 2015; Katz and McLeigh, 2017). Other studies triggered discussions by using a range of attractive activities for children, such as "blob trees" or "message in a bottle" (Adderley et al., 2015) and with the use of photos taken by children (Koch, 2018; Merewether, 2015). We found only two studies promoting video-led discussions (Colliver and Fleer, 2016; Fleer and Li, 2016). Interestingly, we found one study (Fleer and Li, 2016) which conducted the group discussion by organising a community-walk so that children took photos of what they liked and disliked from their community. Later, they invited children to share their experiences during the discussion.

Observations

There is reasonable evidence from our review of studies using observations to listen to what children had to say. Once again, we found a variety of ways and places in which researchers carried out these observations. One of the most common places to carry out observations was the classroom, as evidenced by a range of studies which followed this approach (Cheng Pui-Wah et al., 2015; Fekonja-Peklaj and MarjanoviC-Umek, 2015; McEvilly, 2015; Northard et al., 2015; Reunamo et al., 2015; Wu, 2015), while only in one study the observations were carried out in outdoor spaces (Merewether, 2015) and another where the researchers observed children at home (Wernet and Nurnberger-Haag, 2015). Two studies combined observations with other methods, such as interviews (Wu, 2015) and child evaluations (Reunamo et al., 2015), although in the latter, there was no explanation about the way in which the evaluation took place. Two studies used video-observations (Fleer and Li, 2016; Wu, 2015), and only one (White, 2016) reported to have observed children by following a standardised measure such as the Classroom Assessment Scoring System-CLASS (Pianta, La Paro and Hamre, 2008).

It is noteworthy that most of the observations were carried out cross-sectionally, meaning that they were done at a single point in time rather than in different days. However, we found two studies in which observations were made longitudinally. For example, in a comparative study between Hong Kong and Germany, Wu (2015) observed and video-recorded 48 children playing for "more than five consecutive days" (p. 341) to capture children playing in natural settings. These observations lasted 3 months in Hong Kong and 42 days in Germany. On the other hand, in a case study reported by Wernet and Nurnberger-Haag's (2015) the authors observed a child aged 3 years and 9 months during two consecutive weeks at her home.

Children's hands-on activities

We found limited evidence of specific activities where children played a more active role when researchers needed to collect information from their own environment. For example, in Green's study (2015), while conducting home visits, children led a house-tour after which the researcher conducted informal interviews. Similarly, in Merewether's study (2015), participating children took the researcher on tours indoors and outdoors at their school, pointing and photographing spaces of interest for children. Fluckiger et al. (2018) asked children to take the researchers on a tour to a place where they liked to learn. The authors of these three studies reported that child-led tours provided them with relevant and insightful information about the way in which they perceive their world, and at the same time promoted children's agency. Nonetheless, there is an increasing emphasis in the literature on allowing children to take photos with cameras or digital devices aimed at collecting relevant information pertaining to their interests from indoor and outdoor spaces (Adderley et al., 2015; Almqvist and Almqvist, 2015; Fleer and Li, 2016; Koch, 2018; Merewether, 2015; McEvilly, 2015; Wahle et al., 2017; White, 2015), after which, researchers conduct either interviews or group discussions. This seems to be a very common approach to listening to children's voices.

Discussion and Conclusions

Evidence obtained from this systematic literature review suggests that interviews are by far the most common methodological strategy to listen to children's voices, followed-to a lesser extent-by observations carried out by researchers. Our findings also suggest that group discussions are another strategy used by researchers, although they are not as common as interviews. Interestingly-and perhaps worryingly-, we found limited evidence related to strategies where children play an active role (i.e., child-led tours) and which, reportedly, provide very relevant and insightful information regarding the ways in which children perceive their world. There is evidence to suggest that a common and clear approach used by researchers when interested in listening to what children have to say is the combination of various data-collection strategies in order to triangulate the information obtained, namely, interviews with observations, group discussion with observations, group discussions with interviews, etc. This seems to be consistent with research elsewhere (Aubrey and Dahl, 2005; Clark, 2007; Hennessy and Heary, 2005). Likewise, according to the results, the materials and activities used by researchers to elicit children's narratives are becoming increasingly more creative. These materials include dolls, puppets, pictures, images, photos, scenarios, play-based activities, story-completion, blob trees, vignettes, community walks, photos taken by children, and drawings.

It is argued that conducting interviews is, in essence, a gold standard approach in research which allows to gather first-hand experiences of participants in the form of perceptions, attitudes, views, ideas or experiences given the active exchange of information between interviewer and interviewee (Bryman, 2016; Padgett, 2016; Orcher, 2016). On these grounds, it is not surprising to see interviews as the most common strategy in educational research with children, finding which is also consistent with previous studies conducting interviews (Eder and Fingerson, 2002; Irwin and Johnson, 2005).

On the other hand, conducting observations seems to pose some challenges when it comes to listening to children's voices. Studies included in this review varied greatly in terms of the way in which observations were used. While in some cases observations were indeed used to collect children's voices, in other occasions this was not the case. Hence, this strategy was used to gather only contextual information which could complement another strategy used (i.e., focus groups, interviews, etc.). Nevertheless, while we are aware of the fact that gathering contextual information in the early years is essential (Garbarino, 2017; Martinez, Taut and Schaaf, 2016; Skwarchuk and LeFevre, 2015), our evidence suggests that observations should be used in a more systematic way to allow researchers to capture children's voices. Interestingly, we found only one study where it could be argued that children's accounts were not trusted. Wu (2015) video-recorded observations of children's play in order to establish the differences between what children did and what they recalled when interviewed. This suggests a lack of trust in children's accounts, or the need to prove that they were correct. Future reviews should focus on analysing studies to identify the extent to which specific and additional strategies are used to verify children's views-from the adults' perspective.

Results from this study also revealed that discussion groups can be an effective strategy to listen to what children have to say in the presence of their peers and significant adults when a secure and friendly environment is promoted, which is consistent with previous studies (Darbyshire et al., 2005; Mortimer, 2004). In studies from this review in which the researchers used discussion groups, they turned to a variety of material and attractive play-based activities to trigger children's active participation, which seems to be consistent with play-related principles of children's learning (Daubert, Ramani and Rubin, 2018; Maher and Smith, 2017; Robertson, Morrissey and Rouse, 2008) and let the participants to feel included and their voice valued. The effectiveness of using a range of material and hands-on activities when working with children is well documented in the international literature (Maher and Smith, 2017; Mortimer, 2004). This is the reason why we consider that researchers should continue to use this strategy.

Notably, findings from this review revealed limited cases where children are allowed by adults, to take the lead (notice the emphasis in italics) in activities proposed by adults (e.g., house/school child-led tour, children taking photos and leading adults), giving them the freedom to capture their interests, likes dislikes and so forth, in indoor and outdoor contexts. Moreover, the evidence seems to suggest that when using these activities, children were importantly empowered, which is in itself a way to promote a range of personal-related skills such as independence, self-concept, self-confidence, autonomy, self-esteem amongst others, as suggested by developmental psychologists (Orth and Rubins, 2014; Schore, 2015). We argue that this approach should be used in a more systematic way in educational research with children since the evidence suggests that relevant and significant information from the child's point of view was gathered in the few studies applying it. Nevertheless, our evidence also suggests that issues related to adult-child power imbalances are still present in research with children. This leads us to point out that this aspect must be further analysed, as suggested by a number of scholars (Fargas-Malet et al., 2010; Gabb, 2010; Smart, 2009; Tangen, 2008).

The findings of the study reveal that, in most studies, activities were organised and proposed by adults, leaving little room for children to decide what to do and how to do it. While it is well accepted that the researchers must implement the most effective methods to gather children's voices- again, according to the adult only-, perhaps it is time to involve children in decision-making processes and appreciate and acknowledge their agency and, hence, empowering them to decide how they want to share their views. This notion is further supported by the contemporary view of the child as an active and capable participant in society (Brannen, Hepinstall and Bhopal, 2000; Christensen and James, 2008; James and Prout, 1996; Mayall, 2002), capable of sharing his/her views of the world he/she lives in-which happens to be the very same world adults live in (Clark, 2007; Darbyshire et al., 2005; Penn, 2004; Rinaldi, 2005)-rather than being an object from which the researcher obtains information.

While this review has endeavoured to synthesise relevant findings from a wide range of eligible literature as possible, it is also important to acknowledge any potential limitations of the literature review undertaken by the team. The inclusion and exclusion criteria, as well as the screening, quality and relevance appraisal processes may have limited our ability to find relevant studies in the international literature which, indeed, listen to children's voices prior to 2015 and in other countries not included in this review. While the reduced number of studies included may be considered a limitation, it also reflects the lack of studies in this field specifically since the publication of the 2015-2020 agenda related to the SDGS.

Findings from this review suggest that interested parties and policymakers should be aware of the ways in which children can be listened to, and perhaps, come up with innovative child-empowering strategies. This might give stakeholders confidence to carry out different activities in which children's agency is promoted and their views are taken into account in school and home settings. Teachers may require training to acquire new strategies which allow them to effectively listen to children voices at schools. These findings are of relevance to international researchers, since these could prompt them to create innovative strategies to conduct research in this respect, which provide opportunities for children's agency to be encouraged, so that they take the lead, as well as opportunities to empower children to express their views on matters which are important to them.