Introduction

Since the 1920's in Brazil, propositions were developed and non-school institutions were implemented which were inspired by the American playgrounds organized by the Playground Association of America. Similar institutions were also identified in other Latin American countries like Argentina, Chile, Mexico and Uruguay. The Parque Infantil (childhood park), implemented in the city of São Paulo in 1935, was the main institution of this kind in Brazil. From the 1940's onwards, parques infantis were established in other cities in the state of São Paulo and in other states in the country, and in the second half of the 1970's, they were turned into Escolas Municipais de Educação Infantil.

In this article, we will analyze the educational propositions for these institutions. We focus on the English Infant School's playground, organized by Samuel Wilderspin in the 1820's; the Playground Association of America, in the early 20th century; and then, the Parque Infantil and other Brazilian and Latin American institutions. It is undeniable that each of the contexts in which these institutions developed have their own specific features. But points in common can also be found in evidence referring to affiliations or citations of the past which are not explicit and evanesced in the narratives about their history. The compositions that led to their implementation were made through social policy arrangements that addressed not only pedagogical and school matters but also physical education, urbanism, and hygiene. We will develop these strands based on theoretical and methodological contribution from the history of education in the framework of social relationships (Ginzburg, 2007; Kuhlmann Jr, 2019; Kuhlmann Jr. & Leonardi, 2017; Thompson, 2001; Williams, 1992).

The Playground in Infant School

The documents and studies about the history of the playground mention a remote influence from Froebel's pedagogical propositions for the Kindergarten. However, an illustration in the book School Architecture, published in the United States in 1848, indicates another model for the implementation of American playgrounds: the Infant School, an institution organized by Samuel Wilderspin in England, which was not identified in the texts of the Playground Association of America. The book, which presented different models of common school buildings, was written by Henry Barnard, one of the pioneers of the American Common School Movement. In a topic about plans of common school buildings and courtyards, Barnard reproduced an illustration of the Infant School's playground and argued about Wilderspin's propositions and the importance of that space, which allowed alternating play and study time (Barnard, 1849).

In 1823, Wilderspin published the book On the Importance of Educating the Infant Children of the Poor, where he systematized, in its 184 pages, the propositions he had been applying at the Spitalfields Infant School since it opened, in 1820, with a view to guiding the constitution of a system of infant schools. The book was revised and rewritten a few times; in 1840, it was renamed Early Education, and in 1852, its "carefully revised" eighth edition was published with 351 pages and under the title The infant system, with the subtitle for developing the intellectual and moral powers of all children from one to seven years of age.

The 1823 book already includes a chapter dedicated to the playground, which it did not define as a specific institution, but rather a necessary annex to the school space, unlike the specific, non-school institutions that were implemented in the late 19th and early 20th centuries in the United States. According to the author, an Infant School without a playground would be harmful to children:

To have one hundred children or upwards in a room, however convenient such room might be in other respects, and not to allow the children proper relaxation and exercise, which they could not have without a play-ground, would materially injure their health, which is a thing in my humble opinion, of the first importance. (Wilderspin, 1823, p. 170)

The same passage appears in the 1852 edition, but in the 1823 book, the author's considerations are predominantly moral. The playground could be compared to leaving a child to their own devices, i.e., the child would let out their inclinations and the effects produced by their education. If they were prone to fighting and arguing, then the teacher would have the opportunity to give advice on the unsuitableness of their conduct, whereas if the child remained only in the classroom, that would not manifest at school, only when they were out in the street. This space for playing would also help the child like school better (Wilderspin, 1823, pp. 170-174).

In turn, in 1840, toys and games gained relevance, along with moral education. The book was quoted by Barnard (1849), who reproduced an illustration from that edition and presented the organization of that outdoor space with its materials and the practices to be developed there.

In the 1852 edition, the proposals for the playground are no longer restricted to moral considerations and appear in two chapters: the fifth, about the principles for early childhood education, and the sixth, about the requirements for an infant school.

In the fifth chapter, the playground is presented as indispensable to the institution's educational purposes. In children's education, exercising and the strengthening of physical energies are referred to as the basis for a powerful and healthy intellect. Through games, the child could acquire a great deal of valuable knowledge. By playing, the child would be able to see the book of Nature:

The absurd notion that children can only be taught in a room, must be exploded. I have done more in one hour in the garden, in the lanes, and in the fields, to cherish and satisfy the budding faculties of childhood, than could have been done in a room for months. (Wilderspin, 1852, pp. 77-78)

Physical exercise, inherent to animal life, underpinned the proposition that a good constitution should be the first goal of education. Working habits could not be acquired by restraining children's activities:

Deprive the children of their amusement, and they will soon cease to be the lively, happy beings, we have hitherto seen them, and will become the sickly, inanimate creatures, we have been accustomed to behold and pity, under the confinement and restraint of the dame's schools. I do not scruple to affirm, that if the play-grounds of infant schools are cut off from the system, -they will from that moment cease to be a blessing to the country. (Wilderspin, 1852, p. 80)

The sixth chapter says that the teacher, whether male or female, should live in the school; it also deals with materials, furniture, space organization and the distribution of children by age. In this chapter, Wilderspin does not reproduce the 1840 edition's figure; instead, he presents a simpler representation of the rotatory swing in the playground, which is also on the book's cover. After the same moral considerations as in the 1823 edition, the author disserts on space organization. He recommends paving the ground with bricks for good soil drainage and for preventing children from getting too dirty. Fruit trees should be planted around the playground's walls and in its center in order to cheer the children, while also teaching them to respect private property. A flower bed all around the space was also recommended. All this should provide the opportunity of useful lessons for children.

Wilderspin also expressed his growing conviction about the playground's importance each year. He reported that the experience with balls, hoops and shuttlecocks had not been successful, since balls were often lost by going over the walls, and the other materials caused accidents. Hence the idea of using wooden blocks around four inches long, an inch and a half thick, and two inches and a half wide, which were very entertaining for children, who built a variety of shapes with them (Wilderspin, 1852, pp. 101-105).

To complete the playground, Wilderspin proposed installing a rotatory swing with a pole about 17 feet tall, on top of which 4 ropes were to be fixed on a pulley for children to rotate - an exercise that should strengthen the muscles and the whole body. The author concluded the chapter by saying that the playground could even be more appropriately called a training-ground (Wilderspin, 1852, p. 105-107). The rotatory swing was an equipment used in playgrounds and in Brazilian institutions, where it was called the "passo do gigante" (the giant's step) (Kuhlmann Jr., 2019).

The wooden blocks, as depicted in the 1840 figure, are very similar to the materials used in kindergarten. While these materials were not as central an element in the Infant School as they were in the Froebelian proposition, evidence shows that these building materials were likely not an original idea of the German pedagogue. It is plausible to suppose that, in both cases, they were an appropriation of popular culture games. We do not known whether Froebel read Wilderspin's book, which is not unlikely, since it was translated into German by Joseph Wertheimer in 1826, with a second edition in 1828, with 410 pages (Wilderspin, 1828). According to Jean-Noel Luc (1999, p.192-3), Wertheimer spurred the debate on children's education not only in Germany, but also in Hungary and Italy.

The Playground in the United States

As for the American playground, the following points are worth noting. Wilderspin's ideas were not mentioned by the movement's leading actors. However, the figure published in Barnard's book was appropriated in the playground historiography and erroneously disseminated as if it were a proposition made by Barnard himself, or even as an image of what one of the first American playgrounds was like (Brett, Moore, Provenzo, 1999; Kuhlmann Jr., 2019).

It is Froebel who appears as the source of inspiration to the American propositions, as mentioned in the first issue of the Playground Association of America's monthly magazine The Playground, in April 1907:

Froebel planned more than eighty years ago the kindergarten, with its plays and occupations, for little children. We propose now to develop a graded system of kinder-welten, - schools with playgrounds and workshops, gymnasiums and manual training rooms, science and art rooms, museums and libraries, lecture rooms and study or club rooms, under a curriculum presenting successive stages of world progress, to the end that the individual child and his environment may act and react in selected lines of racial development. (The Playground, 1907, p. 8)

The magazine, launched a year after the Association was created, featured a letter by the then President Theodore Roosevelt which advocated public playgrounds. The organization named him its honorary president; it also named Baron von Schenkendorff, president of the German Playground Association, an honorary member.

Von Schenkendorff was considered an inspiration for the creation of playgrounds in the United States, which are said to have been implemented as a result of Marie Zakrzewska's visit to Berlin, where she saw sand gardens for children, created by him, and which inspired the installation of a wide sand tank in the gardens of the Children's Mission in Boston, in 1885 (Hansan 1925).

The Playground's fourth issue developed the idea of kinderwelten, the children's world, which expanded Froebel's idea with play schools. Play schools should congregate playgrounds, play farms, holiday schools and their shops:

Play Schools are necessary for the development of expression, power, personality - one-half of the work of public elementary education, unrecognized or undeveloped in the present system of education, which confines its attention largely to work of impression, refinement, culture. (Stewart, 1907, p. 7)

Folklore was one of the activities recommended by the Playground Association of America. The program of the First Annual Playground Congress, held in 1907, included the performance of folk dances from Poland, Bohemia, Italy, Greece and Norway (The Playground, n.3, p.8). At the Second Annual Playground Congress, held in 1908 in New York, the national and folk dance festival was considered the most beautiful event in the meeting. The folk dances performed by the children came from various nationalities: Italian, Polish, Spanish, Irish, Bohemian, Russian, Swedish, Hungarian, Scottish, German and "negro" (sic) (Playground Association, 1909, pp. 48-49).

Folk dance was supposed to provide controlled situations in which recognition of the cultural differences of the immigrant population should be a means for their integration into American society. By feeling that their cultural heritage was appreciated, newcomers could more easily develoployalty to their new nation. Dancing together was supposed to make them less attached to their differences and more aware of their individual efforts as subordinates to the interests of the group (Mooney-Melvin, 1983).

P.A.A. president Luther Halsey Gulick considered that it was not enough to regard games and dances as a safety valve, as something of moral value that should provide an opportunity for innocent consumption of joyful energy:

They constitute, we believe, a positive moral force, a social agency, having had in the past and are destined to have in the future a great fonction in welding into a unified whole those whose conditions and occupation are exceedingly diverse. (1909, p. 433).

The association had its name changed to Playground and Recreation Association of America in the mid-1910's and to National Recreation Association in the 1930's. Removing the Playground name possibly marked the end of the advocacy of playgrounds organized for children, with a shift of emphasis towards playground as a space for gymnastics or recreation exercises in schools or public parks, although its original proposition remained within early childhood education schools (Frost & Woods, 1998).

Physical Education and the Playground in Latin America

There are several indications of the American inspiration for the installation of institutions similar to playgrounds in Latin America.

In Brazil, Frederico Gaelzer, who was an athlete with the Associação Cristã de Moços in Porto Alegre, in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, was awarded a scholarship to study in the United States, at the George Williams College, an institution linked to the YMCA, in 1918. It was not until 1926 that he returned to Porto Alegre, where he organized, with the local government, the Jardins de Recreio (recreation gardens), a local version of the playgrounds (Feix & Goellner, 2008). According to Gomes (2006, pp.105-106), before his return, he worked at the YMCA in Mexico and Uruguay.

The name Jardim de Recreio is part of the references to Froebel and the playground. In the Brazilian case, other denominations were used, such as Campo or Praça de Recreio e de Jogos, Escola de Saúde and Parque Infantil, the last of which became the most common one.

The denomination parque infantil appears as early as in 1915, in the book Eduquemos, by Arthur Porchat de Assis, a pedagogy teacher at the Liceu Feminino Santista and the director at the Instituto Dona Escholástica Rosa, in Santos, on the coast of São Paulo (Faria & Monteiro, 2020). In the book, the author concludes the chapter entitled "Da Educação Physica" (on physical education) by proposing the creation of parques infantis. Assis quotes Froebel, but it is not clear whether there is any influence from the playground model, also because the author's main inspiration for the book is European, rather than American. But the propositions are close to what would later be the implementation of institutions with that model in Brazil:

As for private initiative, may the owners of our beachfront casinos be glad to engage in establishing large parques infantis, where children can enjoy the oxidation of the air, the freedom of their movements and the joy and expansion of their feelings. Nothing can be more attractive than a parque infantil! Early in the morning, may the families let that chatty band of children seek in the parque the most innocent motives for exchanging ideas and affection, sometimes darting in the long lanes, by foot, on their bicycles, on their carrinhos de bodes (goad carts); sometimes building their little sand houses by the lake of crystal water; sometimes building artistic palaces with Papá Froebel's wooden cubes and materials; finally, all that expresses - life, health and joy. The children will spend hours oblivious of all else, healthily enjoying the influences of this real and artificial environment. Real due to direct closeness to nature, whose external physical elements will work by restoring their bodies in general; artificial due to the educative effects that art creates in the choice of games, in the variety of occupations, always improvised and activated by the directors at these infant centers. (Assis 1915, pp. 28-29)

In 1941, Nicanor Miranda, the then head of the Education and Recreation Division of São Paulo, in charge of the city's parques infantis, published a book about the dissemination of parques infantis and parques de jogos. With regard to Latin America, Miranda presented information about initiatives in Mexico, Cuba, Uruguay, Argentina and Chile. About Mexico, he referred to the parks as a development of the missiones culturales, since 1926, and highlighted the role of physical education teachers in restoring traditional Mexican games and dances, which was carried out in the childhood park of Xalapa. In Cuba, he mentioned the creation of the Corporate Council of Education, Health and Beneficence, in 1936, in the Batista administration, which opened parks for children and youths, and he highlighted the José Marti park, in Havana. In Uruguay, Miranda said that efforts to promote physical education had been taking place since 1923, with the plazas de desportes, which he translated as parques de jogos (game parks), some of them with a rincón infantil (children's area).

As for Argentina, he referred to the creation of the Direción de Plazas de Exercicios Fisicos y su Regulamentación, in 1919, which organized game squares, holiday camps, clubs of gardener boys and childhood recreation areas. With regard to Chile, he mentioned the creation of game squares since 1923, many of which were said to have been closed because the required services were not implemented, and the staff's work was often limited to installing the equipment. (Miranda, 1941, pp. 15-19)

However, documents should be viewed with caution. Miranda's information came from bibliography he accessed and which contains errors. For example, with regard to Uruguay, Miranda refers to the document by Julio Rodríguez, Plan de ación de la Comissión Nacional de Educación Física (CNEF), from 1923. But the initiatives in Uruguay were underway as early as in 1911, the year of creation of the commission where Rodriguez would later serve as technical director. In 1913, the Plazas Vecinales de Cultura Física were created, and in 1915 they had their name changed to Plazas de Desportes (Scarlato, 2015). Perhaps Miranda made a mistake, or there was a graphic error in his study, since he cites as reference the 1923 report and claims that his information about Uruguay comes from the "latest official report" from that country, where there were already 85 plazas de desportes (Miranda, 1941, p. 17).

About Uruguay, Scarlato (2015, pp. 111-112) cites the 1913 book by Juan Arturo Smith, president of the CNEF, which paid tribute to the United States by referring to the book American playgrounds, by EB Mero, from 1908. Miranda (1941) also cited this book as a reference for writing about the United States. According to Scarlato, Smith considered that the plazas vecinales overcame the playgrounds for two reasons: they were open not only for children and adolescents, but for mothers, fathers and young and elderly people; and they incorporated an "organized management". Smith appointed Jess Hopkins technical director of the first plaza vecinal. Hopkins was an American living in Uruguay since 1912; he had a degree in physical education from the Springfield College, linked to the YMCA, and became head of the Department of Physical Education of the Uruguayan Associación Cristiana de Jóvenes (ACJ). Later, by Hopkins' appointment, Julio Rodríguez went to study physical education at the Springfield College.

It is worth highlighting that the president of the Playground Association of America, Luther Halsey Gulick, was also head of the Department of Physical Education at the Springfield College, previously denominated YMCA International School, in Massachusetts (Dogliotti, 2013, p. 2).

Urbanism and the Playgrounds

The growth of cities, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, brought the subject of parks and recreation into the debates of urbanism and landscaping. In 1923, after completing his Master's at the University of Columbia, Gilberto Freyre wrote the essay Ludum Pueris Dare, published in the Diário de Pernambuco newspaper, where he mentioned the playgrounds:

I wish my very young fellow countrymen knew how to resist our terrible habit of turning children into little men as soon as possible. It is bad enough that this borough, like the other boroughs in Brazil, is a sad city without recreational areas for the little ones, without lawns where they can run, without tanks where they can play with paper ships, without anything that stimulates joy in them. And, unlike the children we see in happy flocks on the grass of parks in London and Berlin, in the Tuileries and in the play-grounds of any city in the United States and Canada, the boys here are sad creatures, candidates for tailcoat and early baldness. (1979, p. 141)

In 1925, Gilberto Freyre mentioned again, in another essay, the need for areas where children could play freely and, in 1929, as a secretary to the governor of Pernambuco and a teacher of sociology at the Escola Normal do Recife, he made notes on research carried out by his students in the city and on the imminent implementation of playgrounds. Freyre had conducted studies on modern urbanism, and he projected: "Recife will be the first Brazilian city to have playgrounds". It is not known whether those were actually implemented, since due to the political changes in Brazil in 1930, the governor was deposed, and Freyre followed him in his exile abroad (Freyre, 2006, p. 314).

In 1930, in the city of São Paulo, the Playground of D. Pedro II Park was inaugurated as a result of arrangements conducted since the 1920's in the Rotary Club, whose president was Doctor Edmundo de Carvalho, MD, and which had the city's future mayor Luiz Ignácio de Anhaia Mello as a member (Dalben, 2016). To urbanists, active recreation for children would provide a contact with nature. Soares analyzes how, in the early 20th century,

educators, scientists, artists, urbanists and doctors contribute to form a set of ideas about life in the open air in which the desire to escape towards nature conceived as a source of recovery of lost energies and recovery from degeneration is central. (2016, p. 18)

This concerns not only a nature external to the urban environment, but also the development of propositions of space organization that should bring nature into the city. The urbanist ideas were present in the playground of D. Pedro n Park, in São Paulo, inaugurated on December 25, 1930. That Christmas, a festival was held which was attended by authorities and included the distribution of toys and candies to children.

The playground probably began to operate before that date, which was just an official celebration, since a news story published seven months earlier in the Diário Nacional announced that the construction works were in the final stage. The text's starting point was the conceptions of "modern urbanism" regarding the restoration of contact with nature, indicating the trend of bringing the countryside into the city through the implementation of "active recreation". With a swimming pool for children up to 5 years old ready, the city's first recreation park awaited the last touches in its shed and the delivery of seesaws, swings and games which were being manufactured at the city's Liceu de Artes e Ofícios. Three hundred children were expected to visit the place each day. Considering urbanism as a matter of education, the news story presented the playground's educational purpose:

children's physical improvement will be accompanied by their mental education by means of educative prelections, classes in the open air lasting a quarter of hour, singing, recitation, etc (...) Children will breath the free countryside atmosphere amidst the city of skyscrapers ("Estão quasi promptas", 1930)

Hygiene - Education and Health in the Parques

In 1931, the playground of D. Pedro II Park had its name changed to Escola de Saúde (health school), as a result of a partnership between the Crusade for Childhood Association and the municipality of São Paulo, which was based on a program for children aimed at reducing child mortality and promoting education for children's physical and moral health. The program was designed by Maria Antonieta de Castro, the secretary-director of the institution, which had Pérola Byington as director-general. De Castro was a sanitary educator and had held various positions at both the Sanitary Service and the Hygiene Institute of São Paulo. The Crusade for Childhood itself was born within the Association for Sanitary Education and became an autonomous entity in 1931.

On October 12, 1931, the Escola de Saúde was officially inaugurated as part of the celebrations of the Children's Week, a festivity implemented by the Crusade for Childhood. At the ceremony, Pérola Byington, director of the Crusade, explained that the school's purpose was to attract children from nearby neighborhoods such as Brás and Moóca, both of which had a significant population of factory workers at the time. According to her, the playground of D. Pedro II Park was nearly derelict, with only a daily guard but no guidance to users. The municipality accommodated the Crusade's request and granted it the space, which would thus have an educational program with conferences, parent meetings, gymnastics, games, toys, educational excursions, specialist medical gymnastics, festivals and sports competitions. In the afternoon the same day, Byington and de Castro attended the continuation of the Children's Week celebrations at the Municipal Theater, where Fernando de Azevedo held a conference titled A Saúde e a Escola Nova (health and the new school). At the opening session, the Director-General of Education of São Paulo, Lourenço Filho, read a letter by the then Brazilian president Getulio Vargas where he expressed his interest in the Children's Week promoted by the Crusade and in a campaign focusing on problems related to children in the press, the radio and conferences. Fernando de Azevedo's speech addressed the need to cultivate children's health as well as build their character and educate their intelligence ("Iniciou-se ontem", 1931).

About the educational proposition of the Escola de Saúde, which had sanitary educators hired as such, de Castro wrote:

In 1931, the Crusade organized and operated, in D. Pedro Park, the "Escola de Saúde", for the physically weak, with a special regime of physical exercises, hydro and heliotherapy, in which it also organized the first Children's Library of Sao Paulo, with 500 books. In 1936, absorbed by the Municipal Government, this School became the Parque Infantil that still exists (Castro, 1956, p. 2)

The city of Santos also inaugurated its Escola de Saúde under the aegis of the city's Rotary Club, even before the one in São Paulo, on February 23, 1931. In 1942, it was incorporated into the municipal government under the name of Parque Infantil (Cunha, 2018).

As in São Paulo, the plan for the Escola de Saúde in Santos included educators hired by the state who, helped by municipal assistants, would teach "respiratory and Swedish gymnastics, instructive recreation, civic instruction and notions of things and hygiene, in addition to the practice of heliotherapy." (Escola de débeis, 1931)

The term Escola de débeis (school for the weak), which was the heading of the news story, was also used in relation to the Escolas de Saúde in São Paulo, and referred to the proposition of open-air schools and holiday camps, which were disseminated since the early 20th century in Europe and Latin America (Amaral 2016, Dalben 2009, 2019). They were intended as measures to overcome physical weakness and prevent the contagion of tuberculosis in times prior to the BCG vaccine.

The sun and nature as promotors of health were touted by hygienists. In 1916, Moncorvo Filho, head of the Institute for Childhood Protection and Care of Rio de Janeiro, made a communication to the First Medical Congress of São Paulo about Brazilian initiatives regarding heliotherapy. In addition to his work, he highlighted the names of "Clemente Ferreira, Alfredo Ferreira de Magalhães, Augusto Paulino, V. Veiga, Jader de Azevedo, Ribeiro de Castro, Oliveira Botelho, Julio Novaes and others" who, three years earlier, began to practice the "new naturist method" (Moncorvo F° 1917, p. 8). In the text, he referred to the creation of a special heliotherapy service, with the installation of a solarium in the Moncorvo Dispensary, and presented results of the treatment of 14 children and adolescents.

On May 4, 1924, Moncorvo Filho and Alves Filgueiras inaugurated the "Heliotherapium", "an establishment especially dedicated to prophylaxis and healing through sunbathing". In the speech he made at the inauguration, Moncorvo said that one of the institute's main purposes was:

to provide care especially for weak, undergrown, anemic or rickety children to be radically transformed in their physique by the marvelous effects of life in the open air, also learning and playing under the influx of rays employed in a methodical and scrupulous manner. (Moncorvo F° 1924, pp. 6-7).

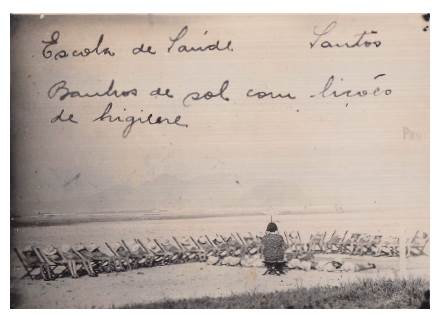

With regard to heliotherapy, the images of children in photographs of the Escola de Saúde in Santos follow the pattern of open-air schools in Europe or other Latin American countries. Children wear wide-brimmed hats and swimsuits. In one of the photos, they are in formation, with the words "gymnastics in the sun" written on the photo; in another, a classic model: most of them lying on canvas chairs arranged in a semicircle, a few on mats on the ground, and the dressed teacher is sitting on a stool in front of them, with the caption "sunbathing with lessons of hygiene" (Cunha 2018, p. 64).

Source: the Duarte Family collection. Laboratory of information, Archive and Memory of Education (LIAME), Unisantos.

Figure 3 Sunbathing at the Escola de Saúde in Santos, n. d.

The denomination Escola de Saúde had been used before to refer to the Santos institution and the playground in D. Pedro ii Park. In July 1930, a news story was published about the Escola de Saúde at the Centro de Saúde (health center) in Bom Reiro, a neighborhood in central São Paulo, installed two months earlier by the state Sanitary Inspection Service. Maria Conceição Junqueira was the person in charge of the Centro, and she told the reporters that the purpose was to turn weak children into robust ones. To that end, they selected 20 malnourished girls and 15 malnourished boys from the João Kopke Primary School, near the Centro de Saúde. They then began to teach them about health and treat them with medicines, respiratory gymnastics and exposure to the sun. After those, the children were served soup or porridge and a fruit. The sanitary educators would also visit the parents to provide counseling. As a didactic strategy, they made a plan of excursions called "going to health city". According to this plan, to arrive in health city, children should stop at each station, which meant putting on 200 grams on a monthly basis:

as in fairy tales, Bath City is the first station on the hygiene road, which goes to Health City and stops at the stations: Spring of Clean Water. Valley of Fruits, City of Healthy Eating, Exercise and Rest, Pure Air and Sunlight, Milk Farm, Potato Field, School, Restorative Sleep. ("Apenas de tanga", 1930)

Final Considerations

The relationship between the propositions for the Infant School's playground and the American playground was not direct, but there are interesting points in common which reverberated in the diffusion of this institution across the American continent. The rotatory swing, whose design was detailed in Wilderspin's book, accompanied that diffusion; it was called passo do gigante in Brazil, and was the precursor of other equipment (slides, seesaws, swings, roundabouts) which came to be installed both in institutional playgrounds - organized ones with professional staff - and in playgrounds in a more informal sense - a space for children's fun in squares and parks. No study was found about the repercussion of Barnard's book with regard to school architecture in the United States. But the appropriation of Wilder-spin's image as if it were the precursor design of an American playground is a distorted acknowledgement of that relationship.

Physical education became one of the main bases for disseminating this educational institution. The body is understood beyond the practice of gymnastic exercises, i.e., in cultural expressions such as folkloric ones, and in its relationship with nature, the promoter of healthy development.

Social policy making and the planning of modern cities and their spaces aggregate the interest of urbanists and authorities in the institution. In his letter to the Playground Association of America, the then American president Theodore Roosevelt wrote:

Play is at present almost the only method of physical development for city children, and we must provide facilities for it if we would have the children strong and law-abiding. (...) If we do not allow the children to work we must provide some other place than the streets for their leisure time. (The Playground, 1907, p. 5)

The links between education and health were a strong component of the propositions of these institutions, and were present even after the period indicated in the title of this article. Interestingly, the excursion activity developed at the Escola de Saúde in Bom Retiro was proposed in a very similar way in June 1948.

Between 1947 and 1957, the propositions for the Parque Infantil in the city of São Paulo were disseminated through the Boletim Interno (internal bulletin) of the Division of Education, Social Work and Recreation of the Department of Education of the city of São Paulo, which provided guidance on a monthly basis for the work in those institutions (Kuhlmann Jr & Fernandes, 2014). In the Boletim Interno published that month, Noemia Ippolito, head of the Technical-Educational Section, presented a miniature reproduction of a drawing that existed in the building in Parque Infantil D. Pedro II, with the title "Uma viagem à terra da saúde" (a trip to the land of health) (Figure 4). The drawing should be handed out to children, who, with their taste for handling colored pencils, would paint the images, thus "simulating a real trip" and acquiring essential knowledge about bathing, life in the open air, healthy eating, but also about educational institutions and studying. Was the Bom Retiro proposition used as a model for the drawing still in the days of the Escola de Saúde in D. Pedro II Park, and kept after the change to Parque Infantil?

Source: Boletim Interno da Divisão de Educação, Assistência e Recreio (June 1948)

Figure 4 Sanitary Education.

In the Escolas de Saúde and in the Parque Infantil established in São Paulo, guidelines related to the field of physical education, from the perspective of comprehensive education, were integrated with those of hygiene, from the perspective of open-air schools. In Uruguay, on the other hand, it seems that the aspects of physical education and hygiene followed parallel paths. The Plazas de Deportes received children and young people for recreational exercises, games and sports such as football, volleyball, tennis and boxing (Scarlatto, 2015). In the same period, Escuelas al aire libre were inaugurated in 1913, at the initiative of the Liga Uruguaya contra la Tuberculosis helped by the Cuerpo Médico Escolar and the Dirección General de Instrucción Primaria (Dalben, 2019).

The confluences and distances in the history of these institutions across Latin America are a fertile research field to be explored.

text in

text in