Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Ensayos sobre POLÍTICA ECONÓMICA

Print version ISSN 0120-4483

Ens. polit. econ. vol.32 no.74 Bogotá Jan./June 2014

The Balassa-Samuelson Hypothesis and Elderly Migration

La hipótesis de Balassa-Samuelson y la migración de los ancianos

Oscar Iván Ávila Montealegrea,*, Mauricio Rodríguez Acostab, and Hernando Zuleta Gonzálezc

a Departamento de Programación e Inflación, Banco de la República, Bogotá, Colombia

b Department of Economics, CentER-Tilburg University, Tilburg, The Netherlands

c Profesor Asociado, Facultad de Economía, Universidad de los Andes, Bogotá, Colombia

* Corresponding author. E-mail address: oavilamo@banrep.gov.co (O.I. Ávila).

History of the article:Received May 28, 2013 Accepted December 11, 2013

ABSTRACT

We present a model with two Overlapping Generations (young and old) and two final goods: a) a tradable good that is produced using capital and labor, and b) a non-tradable good that is produced using labor as unique input. We maintain the fundamental assumption of perfect factor mobility between sectors so the model is consistent with the Balassa-Samuelson hypothesis. On top of this, we allow for one of the two generations (the elderly) to migrate between economies. Given the general equilibrium structure of our model, we can examine the effect of the propensity to save on migration and the relative price of the non-tradable good. In this setting, we find that the elderly have incentives to migrate from economies where productivity is high to economies with low productivity because of the lower cost of living (in more general terms, the elderly migrate from wealthy countries to countries with lower incomes). We also find that, for countries with lower incomes, elderly migration has a positive effect on wages and capital accumulation.

Keywords: Tradable and non-tradable, Overlapping generations, Balassa-Samuelson, Elderly migration.

JEL Classification: E44, E52, G21, E21, E22, E23, E24, F21, F22, F43, J14, O41.

RESUMEN

Este documento presenta un modelo con dos generaciones traslapadas (jóvenes y ancianos) y con dos bienes finales: transables y no transables. Los primeros se producen utilizando trabajo y capital, mientras que los segundos utilizan trabajo como único factor de producción. De igual forma, se supone libre movilidad de factores entre los sectores, por lo que el modelo concuerda con la hipótesis de Balassa-Samuelson. Además de esto, se asume que los ancianos pueden migrar de un país a otro. Dada la estructura de equilibrio general, se examinan los efectos que los choques en la tasa de ahorro tienen en la migración y los precios relativos de los no transables. En este contexto, se encuentra que los ancianos tienen incentivos para migrar de economías donde la productividad es alta a economías donde esta es baja, dado el menor costo de vida. De forma similar, se encuentra que la migración de ancianos tiene un efecto positivo en los salarios y la acumulación de capital en las economías pobres.

Palabras clave: Transables y no transables, Generaciones traslapadas, Balassa-Samuelson, Migración de ancianos.

Clasificación JEL: E21, E22, E23, E24, F21, F22, F43, J14, O41.

1. Introduction

The empirical literature on international trade provides evidence on the regularities regarding the relationship between tradable and non-tradable prices and income level of the economies. On the one hand, the prices of tradable goods tend to equalize across economies. On the other hand, due to the absence of arbitrage possibilities, the prices of non-tradable goods may diverge significantly. In particular, wealthier countries tend to have higher non-tradable prices (De Gregorio, Giovannini and Wolf, 1993; Falvey and Gemmel, 1996; Ito, Isard and Symansky, 1997; Égert, 2002 and Dobrinsky, 2003, among others).

This evidence is consistent with the Balassa-Samuelson (B-S) hypothesis, which establishes that the relative price of non-tradable grows when Total Factor Productivity (TFP) of the tradable sector increases relatively to TFP of the non-tradable sector (Balassa, 1964; Samuelson, 1964). This result is based on the assumption of factor mobility between sectors: an increase in the TFP of the tradable sector (ceteris paribus) is met with an increase in wages in that sector and labor moves from the non-tradable sector to the tradable sector. As a consequence, in equilibrium labor decreases in the non-tradable sector and the supply of non-tradable goods falls. Finally, the decrease in the supply of non-tradable goods and the increase in the supply of tradable goods result in an increase in the relative price of non-tradable goods.

A corollary of the B-S hypothesis is that if one assumes purchasing power parity (PPP) for tradable goods, when the TFP growth of the tradable sector is relatively higher in country A than in country B, the real exchange rate of country A appreciates.1

Other branches of the literature explain that workers try to move to high productivity locations because wages are positively correlated with productivity (e.g. Sjaastad, 1962; Hicks, 1966; Borjas, 1989). Therefore, labor migration may serve to reduce wage gaps between rich and poor countries. Now, the rationale for elderly migration is different. Old people do not work, so they do not look for higher wages; on the contrary, they search for low prices (and some amenities); for this reason, they are more likely to migrate to low-wage countries.

Several authors have studied the phenomenon of elderly migration and, particularly, the cases of migration from Northern to Central and Southern Europe, and from the North of the US to the Southern states and Mexico. The pioneers in this field (Lenzer, 1965; Goldscheider, 1966; Lawton and Nehmow, 1976) argue that the elderly migrate in the search for better living standards, and this relate to housing, health services, and living costs in general. More recent studies confirm the results of those authors, and identify other determinants for elderly migration like comfortable climate.2

We with the insights of the B-S hypothesis in a context of elderly migration. With this purpose, we provide a tractable general equilibrium model with overlapping generations (OLG) and two final goods: the tradable good is produced with a standard Cobb-Douglas function using labor and capital; the non-tradable good is produced with a linear production function where labor is the only input. We maintain the fundamental assumption of perfect factor mobility between sectors, so the model is consistent with the B-S hypothesis. Within this framework we find that the elderly have incentives to migrate from economies where productivity is high to economies with low productivity because of the lower cost of living. We also find that when countries differ in their propensity to save, the elderly migrate to economies with lower saving rates due to same reason (lower cost of living). In more general terms, elderly migration is likely to flow from high income to low income countries. Finally, for countries with low incomes, elderly migration has a positive effect in wages and promotes capital accumulation.

The paper is organized in five sections, including this introduction. In the second section we present both theoretical and empirical background on the behavior of prices of tradable and nontradable (TNT) goods and its relationship with TFP. This section also reviews some of the previous evidence on the determinants of elderly migration. In section three, the OLG-TNT theoretical model is presented. This section is divided in three subsections: consumer's problem; firm's problem, and long run equilibrium. In section four we present the predictions of our model regarding elderly migration and capital accumulation, when countries differ in their TFPs or saving rates. In section five, we conclude.

2. Background

2.1. TNT Prices and TFP, Theoretical and Empirical Background

Harrod (1933) establishes that the relative prices of non-tradable goods tend to be higher in those countries with higher per capita income. Kravis, Heston, and Summers (1982) test this hypothesis, finding that production of tradable goods in poor countries is characterized by low productivity levels. Additionally, they show that lower levels of productivity in this sector generate lower wages and, as a consequence, the prices of services and non-tradable goods are lower in countries with lower incomes.

Other authors have studied the existence and quantification of the B-S hypothesis over several economies. De Gregorio, Giovannini and Wolf (1993), using a sample of 14 OECD countries between 1970 and 1985, find that inflation in non-tradables was higher than inflation in tradables. They identify the rising demand for non-tradables and the relatively higher TFP growth of the tradable sector as the two main determinants for this result. Falvey and Gemmel (1996) report a positive correlation between prices of non-tradable services and real per capita income at country level. They argue that this is partially explained by productivity differences across economies. In an study for Asian economies Ito, Isard and Symansky (1997) show that the relation between real exchange rates and economic growth in the B-S hypothesis holds for Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore, but it is not significant for Thailand, Indonesia, and Malaysia. Finally, Gibson and Malley (2007) examine the Greek case, finding that some proportion of the variation on relative tradable prices is explained by changes in sector productivities.

Additionally, there are many studies that test the B-S hypothesis for Central and Eastern European countries motivated by the real exchange appreciation experimented by those countries during their transition to a market economy. For example, Égert (2002) studies six Central European countries between 1991 and 2001, finding that the evolution for the relative price of non-tradables is positively related to the evolution of the relative productivity in the tradable sector. Dobrinsky (2003) tests the B-S hypothesis for 13 candidate countries to join EU in 2004, observing the existence of a negative relation between changes in real exchange rates and relative productivity. Dumitru and Jianu (2008) analyze the case of Romania. They find that had non-tradable prices not been regulated, the B-S effect would have been of 2.6% approximately, and not of 0.6%.

According to the results described in this section, there is a large body of empirical evidence in support of the B-S hypothesis; that is, the difference between tradable and non-tradable prices is explained partially by the difference in sector productivities. Moreover, the evidence shows that richer countries have relatively higher non-tradable prices.

2.2. Elderly migration

The literature on international migration mainly deals with the determinants of labor mobility between countries and the effects of these flows on the destination economies. However, some stream of the migration literature has focused on elderly migration. Old people have very different motivations to migrate, and also have different impacts on the countries in which they arrive.

Regarding the determinants of elderly migration, Cebula, Hughes and McCormick (1981) find that real estate costs affect the probability that individuals migrate between regions within the UK. Cebula (1993) estimates that lower living costs have a significant impact on immigration, especially on elderly immigration. Rowles and Watkins (1993) study the effects of elderly migration over different receiving communities in the US. They present a theoretical model that describes the costs and benefits of migration. The main benefit of allowing immigration is that it can foster economic activity through the increase in the demand of goods and services, and the increase on the stock of capital. Similar results are reported in Fagan (1988), Happle, Hogan and Sullivan (1988), Longino and Crown (1989), Severinghaus (1990), Haas and Serow (1990), Hodge (1991) and Bennett (1993).

Along the same lines, Watkins and Pauer (1992), Severinghaus (1990), Fagan (1988), Gardner (1988), and Rowles, Summers and Hirschl (1985) show that policymakers often consider elderly immigration as an important source of economic dynamism, so attracting elderly immigrants can be considered as a development strategy.

Millington (2000) explores the determinants of migration in the UK for three groups classified by age. He finds that young people migrate from zones with lower raises in average wages and low growth in employment, to zones with lower unemployment and faster growth in wages. While the elderly are interested in lower rates of criminality and better weather, when deciding about where to migrate.

If elderly immigration promotes growth it seems reasonable to understand the conditions that stimulate it. In this sense, Rowles and Watkins (1993) and Longino, Perzynski and Stolle (2002) find warm climate, landscape, opportunity for leisure and entertainment, lower living costs and health and security services as the main characteristics of an attractive destination for elderly immigrants.

The novelty of our paper is that it incorporates the B-S hypothesis into a tractable general equilibrium model of economic growth, and this allows us to analyze in a systematic way the implications of the B-S hypothesis over consumption, migration, and production decisions. On top of this, our model links two separate branches of the economic literature (B-S hypothesis and elderly migration) while providing results that are consistent with the empirical evidence in both fields.

3. Overlapping Generations Model With Tradable and Non-tradable Goods

The basic OLG model with production considers the agents that live for two periods. In each period, agents from two different generations (young and old) coexist. Individuals have the same lifetime preferences. In each period they derive utility from consuming a basket with a tradable and a non-tradable goods. Agents work when they are young (first period of life) and get a wage equal to their labor productivity. A portion of this wage goes to consumption and the remaining is saved; savings are devoted to accumulate capital. Finally, during the second period of life, agents are old and spend all their wealth (savings and capital returns) on consumption. There is no intergenerational altruism.

There are no sources of growth in the long-run (i.e. there is a steady-state with constant output). For instance, our model does not feature aggregate capital externalities, or knowledge accumulation. In this sense, the model is consistent with the conclusions of the neoclassical model of economic growth (Solow, 1956; Swan, 1956) without technical change in which the savings rate is the main determinant of the long run stock of physical capital (income).

We consider two final goods, each produced in a different sector by a representative firm. The tradable good is produced with a standard Cobb-Douglas technology, and non-tradable good is produced with a linear production function. The former uses capital and labor, while the latter only utilizes labor. Finally, we assume that there is no population growth and that physical capital depreciation is equal to 1.

Our analysis proceeds in two steps. First, we consider an economy in autarky, and characterize the long run equilibrium towards which this economy converges. Then, we allow for the interaction between two economies (initially in autarky), and explore the effects of this interaction on relative prices and elderly migration.

3.1. Consumers

Consumers' objective is to maximize their utility, choosing present and future consumption of tradable and non-tradable goods. According to this, and assuming a logarithmic utility function, we have:

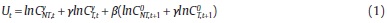

Where CyNT,t is the consumption when the agent is young (y) of the non-tradable good (NT) at time t; CyT,t is the young agent's consumption of the tradable good at time t; C0NT,t+1 is the old agent's (o) consumption of the non-tradable good at time t+1; and C0T,t+1 is the old agent's consumption of the tradable good at time t+1 β ∈ (0,1) is the intertemporal discount factor, and γ > 0 is the relative intratemporal weight of the tradable good in the agents preferences. This weight is assumed to be constant over the lifetime.

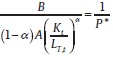

We use the tradable good as numéraire, so we define the relative price of the non-tradable good as:

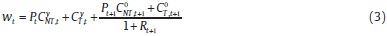

The budget constraint for the representative agent is:

Consumers maximize their utility subject to this budget constraint, where the wage and the net interest rate are also expressed in units of the tradable good. From the first order conditions and the budget constraint we find the optimal expenditures on tradable and non-tradable consumption:

Given the preferences described above, we observe that tradable and non-tradable consumption is directly proportional to labor income, and inversely proportional to the own price. It is also evident that old agents' consumption depends positively on the interest rate too, since it determines the returns to savings.

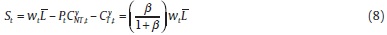

Aggregate saving in this economy is determined by the difference between the total income of the young generation and their total expenditure on consumption. Assuming that in each period there a mass L of young individuals is born (i.e. the total labor input is L) total savings only depend on the total current labor income (i.e. wage times the labor input L), and the discount factor3:

Physical capital is the only reproducible factor in this economy, and it is the only use of investment. Then, in equilibrium total saving at t must be equal to the stock of physical capital at t+1. This result comes from the fact that capital fully depreciates (i.e δ = 1). Consequently:

From (8) and (9) we can observe a positive relation between the discount factor β capital accumulation. This result is straightforward; agent's with a higher valuation for the future decide to save a larger fraction of their income.

3.2. Firms

-

Tradable Sector: We consider that firms in this sector use capital and labor to produce final good. We also assume that they are competitive and have a production technology with constant returns to scale. The tradable good is both a consumption and a capital good. The problem of the representative firm is to maximize profits:

From the first order conditions we have that the marginal cost of each production factor is equal to its marginal cost:

-

Non-tradable Sector: For the non-tradable good, we assume that firms only use labor and they are also competitive. The tradable good can only be used for consumption. The problem of the representative firm is to maximize profits, which are represented by the following function:

From the first order condition, the interior solution must be such that:

The assumption of perfect factor mobility between sectors allows the existence of a unique equilibrium wage in this economy. Moreover, we are only going to focus in the interior solution of the labor allocation. This interior solution arises because of the Inada conditions in the tradable sector. Free labor mobility across sectors means that equations (12) and (14) must be equalized. From this we can characterize the price dynamics during the transition towards the steady-state, that is:

This condition establishes that the relative price of the nontradable good, in the short run, depends positively on physical capital per worker in the tradable sector. And thus, it depends positively on the total capital stock of the economy. In addition, equation (15) is consistent with the B-S hypothesis, since an increase in TFP of the tradable sector relative to the TFP of the non-tradable sector (i.e. an increase in A/B) ceteris paribus, increases non-tradable relative prices.

3.3. Short Run Equilibrium in a Closed Economy

Before analyzing the incentives for elderly and physical capital to move from one country to another, we derive the long-run equilibrium in a closed economy. Then we open the economy and explore the effects of this on elderly migration, and trading patterns.

Having relative prices as a function of physical capital, and physical capital as a function of the number of workers on tradable sector, we must determine the number of workers in each sector in order to characterize the steady state.

From the first order conditions of the consumer's problem we have:

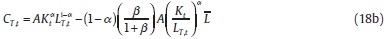

Aggregating tradable and non-tradable consumption for young and old individuals, we obtain:

By assumption, only the tradable good serves both as consumption and capital good. Thus, in autarky, the non-tradable consumption must equalize non-tradable production and tradable consumption must be equal to production less savings (capital accumulation), we find:

Labor endowment of the young representative agent ( ) is constant and it is inelastically supplied, i.e. LNT,t+ LT,t =

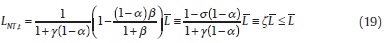

) is constant and it is inelastically supplied, i.e. LNT,t+ LT,t =  . Therefore, from (16), (17), (18a) and (18b) it follows that:

. Therefore, from (16), (17), (18a) and (18b) it follows that:

Where  is the savings rate. Labor allocate to the tradable sector is thus:

is the savings rate. Labor allocate to the tradable sector is thus:

Equations (19) and (20) show that the number of workers in each sector is constant during the transition to the steady state; consequently, physical capital in t+1 depends only on the parameters of the economy and the stock of capital in t. Furthermore, the dynamics of the relative price are fully dictated by the evolution of the capital stock.

Proposition 1: The number of workers in the non-tradable sector depends inversely on: i) tradable consumption importance on the utility function (consumer's preferences), and ii) labor share on tradable production function; and iii) the discount rate.

Proof:

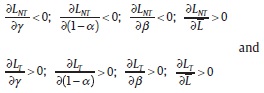

From (19) and (20) it directly follows that:

Note that i) is a result of consumer's preferences, since a higher preference for tradable goods, and services implies a higher allocation of resources in this sector, reducing availability of labor for the non-tradable sector; ii) comes from the fact that the more labor intensive tradable sector is the more resources this sector gets; and, iii) comes from the positive relationship between the propensity to save and the discount rate. As physical capital is the only reproducible factor, a higher discount rate implies a higher stock of physical capital, which increases labor productivity in the tradable sector, so the number of workers in this sector increases, due to the free labor mobility.

3.4. Long Run Equilibrium in a Closed Economy

In order to characterize the transition of the economy to the steady state we use equations (8), (9), and (12) to get the evolution of physical capital:

Using the definition of steady state (i.e. variables do not change over time, Kt = Kt+1 = Kss) we have:

Proposition 2: The capital stock per worker in steady-state depends negatively on the fraction of workers in the tradable sector, and positively on the marginal productivity of workers in the non-tradable sector.

Proof:

It follows directly from equation (22).

This result comes from the fact that workers marginal productivity in the non-tradable sector is constant, and this productivity determines labor remuneration in the whole economy. In this way, a higher B reduces the number of workers in the tradable sector, increasing labor productivity in this sector, and then equalizing wages in both sectors; this means that a higher B increases wages, which in turn increases total savings, and so the stock of physical capital also increases. On the other hand, from equation (23) we observe that relative prices are positively related to the economy's stock of physical capital.

From equation (15), the relative price of the non-tradable good only changes when the physical capital does, because the number of workers remains constant over time. This relationship shows that countries with a higher initial stock of physical capital would have a higher non-tradable relative price during the transition towards the steady state.

Finally, using equations (11), (20), and (22) we find that the steady-state interest rate does not depend on the TFP of any sector:

In fact, equation (24) implies that the steady state interest rate depends only on the parameters of the utility function and the elasticity of output with respect to capital in the tradable sector. Therefore, if these parameters are the same for different economies their interest rates are the same in steady-state.

4. Elderly Migration

In this section we analyze the effects of opening the economy and allowing for elderly migration (and no factor movements). In this context, we present some scenarios that establish the conditions under which elderly migration between two countries, with different characteristics, would occur. We also analyze the possible effects of these movements on both economies.

We assume that young agents cannot migrate to another country; however, when they are old, this possibility is available to them (i.e. countries are closed to labor migration). Given that countries tend to protect their own labor force by imposing limitations on labor immigration, this assumption seems reasonable. Moreover, we do not explicitly model the elderly migration. Instead, and in line with the empirical evidence, we assume that they migrate to the country with the cheapest non-tradable good. Given that workers are likely to receive higher wages in rich countries while prices are likely to be lower in poor countries, it is sensible to assume that the elderly have incentives to migrate from rich to poor countries.

In particular, we assume that the elderly move from one country to another if relative prices, previous to the openness, are different in both countries4. In this context, elderly would move to the country where prices are lower since they can consume more, and this way their utility would increase.

The scenarios we consider are described as follows: first, we consider two economies which only differ in their initial amount physical capital; then, we assume two economies that are initially in their steady states and they decide to open for elderly migration. Under this framework we consider that these economies differ on their TFP levels or on their saving rates.

4.1. The Balassa-Samuelson Effect During the Transition to the Steady State

Consider two hypothetical economies, which differ only in their initial stock of physical capital. The economy that starts with the lower stock of physical capital has cheaper non-tradable goods and services during the transition to the steady state —see equation (15)—. If we allow for elderly migration, they would move to the cheaper country (the one with lower initial capital). Note further that because these economies do not differ in their parameters, in the long run they converge to the same steady state. In this case, if both countries open their economies in the steady state, there is not elderly migration; however if they open during the transition, elderly would move to the country with lower prices; in other words, to the country with lower initial stock of physical capital. These movements would accelerate the transition to the steady state in the receiving country and would delay it in the other one.

4.2. The Balassa-Samuelson Effect (Differences in TFP)

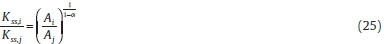

Now consider two closed economies that are identical except for the TFP in both sectors (parameters A and B). Moreover, assume that these economies are in their long-run equilibrium. Let Ai and Bi be country i's TFPs in tradable and non-tradable sector respectively, with Ai ≠ Aj and Bi ≠ Bj, then:

Under this scenario the gap in steady state's capital stock only depends on the relation of the tradable sectors TFPs. Therefore, countries with a higher TFP in the tradable sector have a higher level of wealth in the long run (considering the stock of capital as a proxy for the level of wealth). Rearranging (26), i's non-tradable relative prices are higher if:

Under this scenario, if we allow for elderly migration, they would move to the country with lower prices (lower relative TFPs).

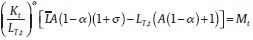

Now we move to explore, in a reduced form, what are the general equilibrium effects of elderly migration in the receiving economy. If the elderly migrate from one country to another, non-tradable consumption is modified in both countries. As non-tradable production only uses labor, this one must be reallocated between sectors in order to satisfy conditions (18a) and (18b). Defining ψ as 1 plus the growth rate of non-tradable consumption due to the elderly immigration, and using (16), (17), (18a) and (18b), we have:

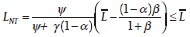

Thus, the new allocation of labor in the non-tradable sector (required to meet the additional demand) is:

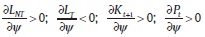

From this expression we can derive that:

From equations (15), (17), (18a) and (18b) we can also find the new allocation of labor between sectors. In particular we have that:

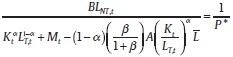

Since elderly migration increases tradable and non-tradable demand in the receiving country, it must be true that the economy starts importing tradable goods. This is the case because physical capital in t is fixed (i.e. the capital stock of each economy is a state variable) and non-tradable consumption would be equal to its domestic production. Defining tradable consumption as domestic production plus imports (Mt) we have:

Also, from equation (15) we know that:

Given these two equations we obtain that:

Which implies that  . In other words, the increase on tradable consumption, caused by elderly migration, reallocates labor between sectors.

. In other words, the increase on tradable consumption, caused by elderly migration, reallocates labor between sectors.

Intuitively, from conditions (18a) and (18b) we know that domestic non-tradable production must be equal to its consumption, and due to elderly migration we have that non-tradable consumption diminishes (increases) in the origin (receiving) country. In the country with higher relative TFP (i.e. the origin country) labor flows from non-tradable sector to tradable sector; then, tradable production increases and the surplus is exported to the other country. Elderly migration also pushes non-tradable prices down; from equation (15) we have that the number of workers in the tradable sector has a negative effect on wages and the relative price of the non-tradable good. As we can see, labor mobility within a country leads the origin economy towards a new equilibrium with a lower level of capital and non-tradable prices.

In the country with lower relative TFP (i.e. the receiving country) we have the opposite effects: aggregate consumption, wages, non-tradable production and prices rise. We can also identify a positive effect of elderly migration for this country, since labor mobility from tradable to non-tradable sector increases wages.

4.3. Different Saving Rates

Given that countries around the world have different dispositions to save5, it is interesting to analyze if differences on the propensity to save also affect the incentives to elderly and physical capital to move. In this context, we consider two economies that differ only on their discount factors (β) or saving rates  . Again, we begin our analysis from the closed economy steady state, and then we allow for elderly movements. In particular, we calculate the effects of the saving rates on the stock of physical capital, the relative prices of tradables and non-tradables.

. Again, we begin our analysis from the closed economy steady state, and then we allow for elderly movements. In particular, we calculate the effects of the saving rates on the stock of physical capital, the relative prices of tradables and non-tradables.

Regarding physical capital, we differentiate equation (24) respect to σ and we get that higher saving rates generate higher levels of capital in the long run. In this sense, we obtain the basic outcome of the neoclassical growth theory: the country with the higher propensity to save ceteris paribus accumulates more capital in the long run.

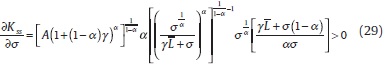

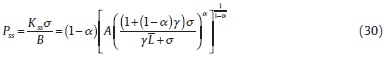

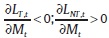

On the other hand, from equations (22) and (23) we find the effect of the saving rate on non-tradable relative prices:

This last equation implies that  > 0 . In other words, countries with a higher propensity to save (σ) have higher non-tradable relative price. Under this configuration of parameters elderly will have incentives to migrate to countries with lower saving rates, because of the lower living costs. This movement, again, increases labor allocation to the non-tradable sector in the receiving country.

> 0 . In other words, countries with a higher propensity to save (σ) have higher non-tradable relative price. Under this configuration of parameters elderly will have incentives to migrate to countries with lower saving rates, because of the lower living costs. This movement, again, increases labor allocation to the non-tradable sector in the receiving country.

In summary, this scenario generates the similar results that the one described on section 4.2. In particular, we observe that higher saving rates generate higher stock of physical capital and nontradable relative prices. In this sense, if two countries which only differ on their savings rates open two elderly migration, they would move from the richer economy to the poorer one, since non-tradables are cheaper.

5. Concluding Remarks

The model developed in this document is consistent with the B-S hypothesis referent to the non-tradable relative prices and real exchange rate dynamics, since it maintains the fundamental assumption of free mobility between sectors. It establishes that not only relative prices but also the real exchange rate depends on the relative TFP between sectors.

Moreover, this model allows us to analyze the effect of TFP differences on elderly migration. In particular, we find that economies with a higher relative TFP have higher living costs, given the B-S hypothesis and under PPP, since non-tradable goods and services are more expensive. The empirical evidence suggests that old people would migrate to countries with cheaper non-tradable goods and services, in the model that means countries with lower TFP.

We also identify that in the country with the higher relative TFP, elderly migration diminishes aggregate consumption, wages, and non-tradable production and prices, and increases tradable production; in the country receiving the inflow of elderly, it has the opposite effects, and it accelerates the accumulation of capital. In other words, elderly migration benefits the receiving economy and facilitates the convergence between the two economies.

Finally, we find that differences on saving rates also generate elderly migration, from the country with higher saving rates to the country with low savings; this occurs because living costs are lower in the latter. Similar to the previous case, the receiving economy benefits from openness to elderly migration.

Notes

1See Appendix.2This change in the subject of study has been motivated by the raise in elderly migration during the last decades. Such is the case of Central European countries as Hungary, where elderly migration has grown from 2% to 10% of the total migration in 15 years (Illés, 2005).

3Given the logarithmic utility function, the income and substitution effect of a change in the interest rate exactly cancel out. Consequently, savings do not depend on the interest rate.

4We assume that there are no costs of moving from one country to another.

5Even economies with a similar degree of development can have dissimilar saving rates (i.e. U.S. and Japan).

References

Balassa, B. (1964). The Purchasing-Power Parity Doctrine: A Reappraisal. The Journal of Political Economy, 72, 584-596. [ Links ]

Borjas, G. (1989). Economic Theory and International Migration. International Migration Review, 23, 457-485. [ Links ]

Cebula, R. (1993). The Impact of Living Costs on Geographic Migration. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 33, 101-105. [ Links ]

Dobrinsky, R. (2003). Convergence in Per Capita Income Levels, Productivity Dynamics and Real Exchange Rates in the EU Acceding Countries. Empirica, 30, 305-334. [ Links ]

Dumitru, I. and Jianu, I. (2008). The Balassa-Samuelson effect in Romania - The role of regulated prices. European Journal of Operational Research, doi:10.1016/j.ejor.2007.12.026. [ Links ]

Égert, B. (2002). Investigating the Balassa-Samuelson hypothesis in transition: Do we understand what we see? BOFIT Discussion Papers, (6). [ Links ]

Fagan, M. (1988). Attracting Retirees for Economic Development. Center for the Economic Development and Business Research, Jacksonville State University, Jacksonville, AL. [ Links ]

Falvey, R. and Gemmel, N. (1996). A Formalization and Test of the Factor Productivity Explanation of International Differences in Service Prices. International Economic Review, 37, 85-102. [ Links ]

Froot, K. and Rogoff, K. (1994). Perspectives on PPP and Long-Run Real Exchange Rate. National Bureau of Economic Research (Working Paper 4952). [ Links ]

Gardner, R. (1988). Attracting retirees to Idaho. A rural development strategy. Idaho Economic Forecast, 9, 28-46. [ Links ]

Gibson, H. and Malley, J. (2007). The Contribution of Sectoral Productivity Differentials to Inflation in Greece. Open Economies Review. [ Links ]

Goldscheider, C. (1966). Differencial Residential Mobility of the Older Population. Journal of Gerontology, 21, 103-108. [ Links ]

Happel, S., Hogan, T. and Sullivan, D. (1988). Going away to roost. American Demographics, 6, 33-45. [ Links ]

Hicks, J. (1966). The Theory of Wages (2nd ed.). New York: St. Martin's Press. [ Links ]

Hodge, G. (1991). The economic impacts of retirees on smaller communities. Research on Aging, 13, 39-54. [ Links ]

Hughes, G. and McCormick, B. (1981). Do Council Housing Policies Reduce Migration Between Regions? The Economic Journal, 91, 919-937. [ Links ]

Illés, S. (2005). Elderly Immigration to Hungary. Migration Letters, 2, 164-169. [ Links ]

Ito, T., Isard, P., and Symansky, S. (1997). Economic Growth and Real Exchange Rate: An Overview of the Balassa-Samuelson Hypothesis in Asia. National Bureau of Economic Research (Working Paper 5979). [ Links ]

Kravis, I., Heston, A., and Summers, R. (1982). The Share of Services in Economic Growth. In: F. Adams and B. Hickman (editors), Global Econometrics: Essays in Honor of Lawrence R. Klein. Cambridge: MIT Press. [ Links ]

Lawton, M. and Nahemow, L. (1976). Ecology in the Aging Process. (A.P. Association, editor). Washington D.C.: Eisdorfer and Lawton. [ Links ]

Lenzer, A. (1965). Mobility Patterns Among the Aged. Gerontologist, 5, 12-15. [ Links ]

Longino, C., Perzynski, A., and Stolle, E. (2002). Pandora's Briefcase: Unpacking the Retirement Migration Decision. Research on Aging, 24-29. [ Links ]

Longino, C. and Crown, W. (1989). The migration of old money. American Demographics, 28-31. [ Links ]

Millington, J. (2000). Migration and Age: The Effect of Age on Sensivity to Migration Stimuli. Regional Studies, 34, 521-533. [ Links ]

Rowles, G. and Watkins, J. (1993). Elderly Migration and Development in Small Communities. Growth and Change, 24, 509-538. [ Links ]

Rowles, G., Watkins, J., and Pauer, G. (1992). Impact of Migration of the Elderly. Lexington, KY, Sanders - Brown Center on Aging, Final Report to the Appalachian Repional Commission, Contract No. 90 - 4, CO - 10257 - 89 - I - 302 - 0321. [ Links ]

Samuelson, P. (1964). Theoretical notes on trade problems. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 46, 145-154. [ Links ]

Severinghaus, J. (1990). Economic expansion using retiree income. A workbook for rural Washington communities. Olympia, WA: Rural Economic Assistance Project. [ Links ]

Sjaastad, L. (1962). The Costs and Returns of Human Migration. The Journal of Political Economy, 70, 80-93. [ Links ]

Solow, R. 1956. A Contribution to the Theory of Economic Growth. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 70, 65-94. [ Links ]

Summers, G. and Hirschl, T. (1985). Retirees as a growth industry. Rural Development Perspective, 1, 13-16. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Agriculture. [ Links ]

Swan, Trevor W. (1956). Economic Growth and Capital Accumulation. Economic Record, 32, 334-361. [ Links ]