1. Introduction

Several years after the Global Financial Crisis, economic growth in many advanced and emerging market economies remains well below precrisis rates. Medium-term growth expectations have been steadily revised downwards since 2011, highlighting uncertainties surrounding medium-term growth prospects (IMF 2015). At the same time, public debt-to-GDP ratios have increased in many advanced and emerging market economies, reaching historical high levels in some of them. Against this background, how can fiscal policy contribute to higher medium-term growth?

Since output volatility can negatively affect medium-term growth through its effects on investment and productivity, fiscal policy can foster medium-term growth by reducing aggregate macroeconomic volatility.1 The idea that fiscal policy can affect productivity growth by operating in a counter-cyclical way has been suggested by Aghion et al. (2005). Their argument is that firms’ ability to borrow to finance investment is typically reduced during recessions: to the extent that higher macroeconomic volatility translates into deeper recessions, it will have a negative effect on investment, especially on productivity-enhancing long-term projects (for example, R&D investment) that are more subject to liquidity risks. This prediction finds empirical support in cross-country regressions (Aghion et al. 2005) as well as in studies based on sectoral- (Furceri and Jalles 2016) and firm-level data (Berman et al. 2007).

Fiscal policy has a stabilizing effect on the economy if the budget balance-to-GDP ratio increases when output growth increases and falls when output growth declines: (i) the more countercyclical government spending is, the higher the effect of fiscal stabilization-a relatively high level of government spending when private demand is low will stabilize aggregate demand; (ii) the more pro-cyclical taxes are, the higher fiscal counter-cyclicality will be-if taxes fall more than output, when output falls, then taxes contribute to stabilize household’s disposable income.

But how stabilizing is de facto fiscal policy and how fiscal counter-cyclicality vary over time, between countries and across phases of the business cycle? Which policy and structural variables determine the effectiveness of fiscal stabilizers? Finally, how much does fiscal counter-cyclicality contribute to lower overall macroeconomic volatility? This paper tries to answer these questions using a novel empirical strategy and estimating time-varying measures of fiscal counter-cyclicality for an unbalanced panel of 61 advanced and emerging market economies from 1980 to 2014. In particular, the contribution of the paper is twofold. First, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first paper that estimates time-varying measures of fiscal counter-cyclicality for a large set of economies, including emerging market ones.2 Second, we examine the effect of time-varying measures of fiscal counter-cyclicality on output volatility.

The use of time-varying measures of fiscal counter-cyclicality overcomes the major limitation of existing studies assessing the drivers and the determinants of fiscal counter-cyclicality that rely on cross-country regressions and therefore are not able to account for country-specific as well as global factors. The key findings of the paper are as follows: (i) fiscal counter-cyclicality has increased over time for many economies over the last two decades; (ii) fiscal counter-cyclicality is positively associated with financial deepening, the level of economic development, trade openness, government size as well as political constraints on the executive; (iii) fiscal counter-cyclicality significantly reduces output volatility. Since output volatility can negatively affect medium-term growth through its effects on investment and productivity, this result suggest that fiscal counter-cyclicality can foster medium-term growth.

While previous work assessing the determinants and the effects of fiscal counter-cyclicality on output volatility using time-varying measures has only focused on a subset of advanced economies (Aghion and Marinescu 2008), there are several studies in the literature that have performed a similar analysis using cross-country regressions for a large set of advanced and emerging market economies. As for the determinants of fiscal stabilization, government size has typically been found to be the most important driver (Gali 1994; Debrun et al. 2008; Debrun and Kapoor 2011; Furceri 2010; Afonso and Jalles 2013). Another important determinant of fiscal counter-cyclicality is the degree of openness: economies that are more open to trade tend to be more exposed to external shocks and may use more actively fiscal policies in order to provide increased stabilization (Rodrik 1998; Lane 2003). Similarly, capital account openness is found to affect fiscal counter-cyclicality as foreign capital tends to flow in (out) during expansions (recessions), therefore increasing the cost of financing counter-cyclical fiscal policies (Aghion and Marinescu, 2008). Studies have also found higher fiscal counter-cyclicality in more developed countries, as these tend also to be characterized by better institutions (or of higher quality) and by higher levels of financial development (Talvi and Vegh 2005; Frankel et al. 2011; Acemoglu et al. 2013; and Fatas and Mihov 2013).

On the effects of fiscal counter-cyclicality on macroeconomic volatility, while the existing empirical evidence on the links between fiscal counter-cyclicality and growth is mixed, several studies seem to agree that a timely countercyclical response of fiscal policy to (demand) shocks is likely to deliver considerably lower output and consumption volatility (Van den Noord 2000; Kumhof and Laxton 2009; Debrun and Kapoor 2011; Fatas and Mihov 2012).

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, a framework for measuring fiscal counter-cyclicality is presented. Sections 3 and 4 develop the empirical strategies to analyze the determinants and the effects of fiscal counter-cyclicality, respectively. The last section concludes and discusses some policy implications.

2. Measuring Fiscal counter-cyclicality

2.1 Conceptual Framework

Fiscal policy has a stabilizing effect on the economy if the budget balance-to-GDP ratio increases when output growth increases and falls when output growth declines: (i) the more countercyclical government spending is, the higher the effect of fiscal stabilization-a relatively high level of government spending when private demand is low will stabilize aggregate demand; (ii) the more pro-cyclical taxes are, the higher fiscal counter-cyclicality will be-if taxes fall more than output, when output falls, then taxes contribute to stabilize household’s disposable income.3

Assessing the degree of fiscal counter-cyclicality in each country i implies estimating the response of the budget balance to changes in economic activity:

where b is the budget balance-to-GDP ratio, Δy is a measure of changes in economic activity-proxied by GDP growth-and β measures the degree of fiscal counter-cyclicality, with larger values of the coefficient denoting higher counter-cyclicality.4

We then generalize equation (1) by introducing the assumption that the regression coefficients may vary over time:

In particular, the coefficients α and β is assumed to change slowly and unsystematically over time its conditional expected value to be equal to its past value. The change of the coefficient β is denoted by  which is assumed to be normally distributed with expectation zero and variance

which is assumed to be normally distributed with expectation zero and variance  5

5

Equation (2) and (3) are jointly estimated using the Varying-Coefficient model proposed by Schlicht (1985, 1988). In this approach the variances  are calculated by a method-of-moments estimator that coincides with the maximum-likelihood estimator for large samples (see Schlicht, 1985; Schlicht, 2003; Schlicht and Ludsteck, 2006 for more details).6 The model described in equation (2) and (3) generalizes equation (1), which is obtained as a special case when the variance of the disturbances in the coefficients approaches to zero.

are calculated by a method-of-moments estimator that coincides with the maximum-likelihood estimator for large samples (see Schlicht, 1985; Schlicht, 2003; Schlicht and Ludsteck, 2006 for more details).6 The model described in equation (2) and (3) generalizes equation (1), which is obtained as a special case when the variance of the disturbances in the coefficients approaches to zero.

As discussed by Aghion and Marinescu (2008), this method has several advantages compared to other methods to compute time-varying coefficients such as rolling windows and Gaussian methods. First, it allows using all observations in the sample to estimate the degree of fiscal counter-cyclicality in each year-which by construction is not possible in the rolling windows approach. Second, changes in the degree of fiscal counter-cyclicality in a given year come from innovations in the same year, rather than from shocks occurring in neighboring years. Third, it reflects the fact that changes in policy are slows and depends on the immediate past. Fourth, it reduces reverse causality problems when fiscal counter-cyclicality is used as explanatory variable as the degree of fiscal counter-cyclicality depends on the past.

2.2 Fiscal counter-cyclicality over time

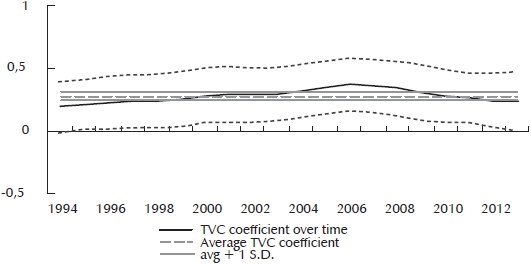

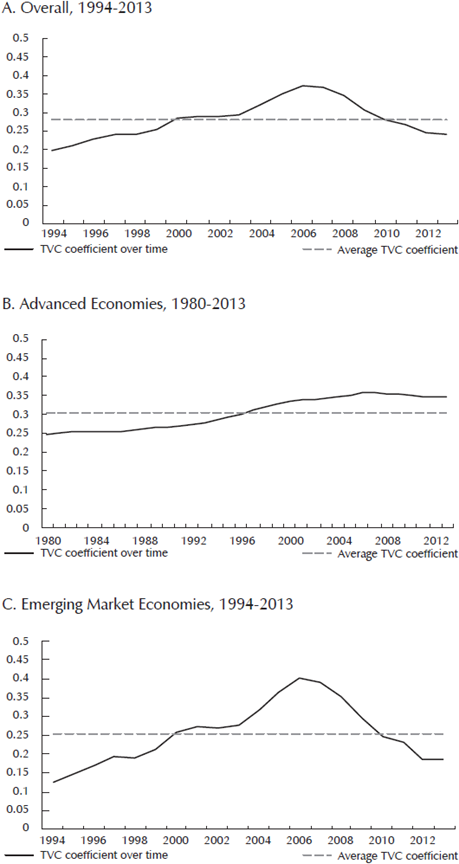

We now report the average level and the time path of the coefficient of fiscal counter-cyclicality estimated in equation (2) and (3) for a sample of 61 advanced and emerging market economies, for which we have estimates of fiscal counter-cyclicalityfor at least 20 years (Figure 1).

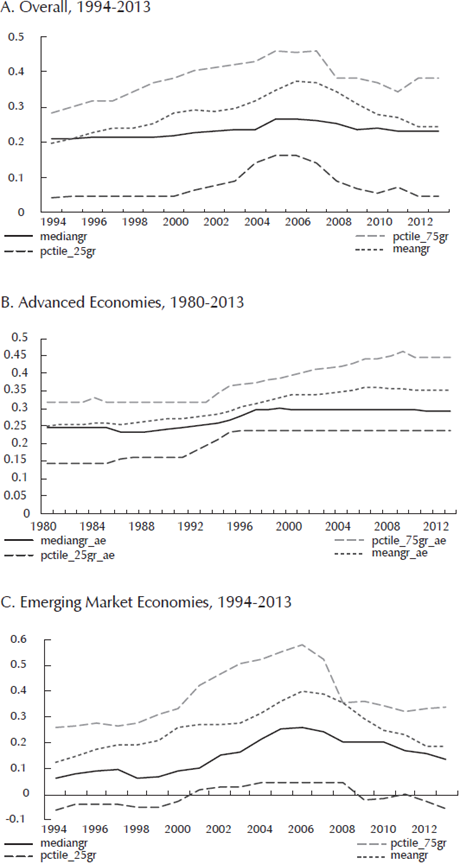

As a first observation, it is worth nothing that the time-average fiscal counter-cyclicality coefficient is positive (about 0.25-0.3), which is consistent with the fact that the budget balance is generally counter-cyclical (Lane 2003; Aghion and Marinescu 2008). Second, the degree of fiscal counter-cyclicality has increased over time (Figure 1), for both advanced and emerging market economies (Figure 2), with the pattern holding for most countries within each group (Figure 3). In particular, the degree of fiscal counter-cyclicality has increased for 41 out of 61 countries in the sample.

Note: Figure displays the time profile of the TVC coefficient estimates for the entire sample, and two income groups, Advanced and Emerging Market Economies. A) includes 18 countries with at least 34 observations; B) contains 61 countries with at least 20 observations; C) contains 25 countries with at least 20 observations; D) contains 36 countries with at least 20 observations. Source: Authors’ calculations.

Figure 2 Fiscal counter-cyclicality over time

Note: Figure displays the time profile of the TVC coefficient estimates for the entire sample, and two income groups, Advanced and Emerging Market Economies. A) includes 18 countries with at least 34 observations; B) contains 61 countries with at least 20 observations; C) contains 25 countries with at least 20 observations; D) contains 36 countries with at least 20 observations. Source: Authors’ calculations.

Figure 3 Fiscal counter-cyclicality over time, within sample

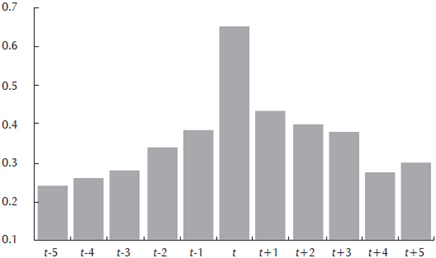

However, while the increase in advanced economies has occurred mostly during the 80s and the 90s, in emerging market economies fiscal counter-cyclicality has increased in the late 90s-early 2000s. Interestingly, fiscal counter-cyclicality seems also to increase during recessions, particular during financial crises (Figure 4).

Note: Figure displays the average value of the TVC coefficient estimates from 5 years prior to the beginning of a given financial crises (“t”) to five years after it began. In each of the three panels averages were computed over a balanced sample. Source: Authors’ calculations

Figure 4 Fiscal counter-cyclicality during financial crises

3. Determinants of Fiscal Stabilization

3.1 Empirical Methodology

This section tests the importance of various macroeconomic and political factors in affecting the degree of fiscal stabilization. For this purpose, the following regression is estimated on a balanced sample of 61 countries for which we have estimates of fiscal counter-cyclicality for at least 20 years:

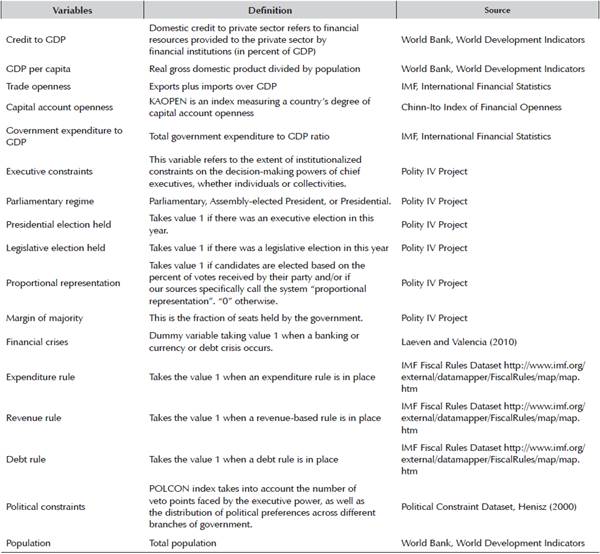

Where δi are country-fixed effects to capture unobserved heterogeneity across countries, and time-unvarying factors such as geographical variables which may affect the degree of fiscal counter-cyclicality (Afonso et al. 2010); γ t are time-fixed effects to control for global shocks; and X it is a vector of time-varying macroeconomic and political variables 7

Macroeconomic variables:

Real GDP per capita: it is expected that fiscal counter-cyclicality is higher in more developed countries, as those tend to be also characterized by a better quality of institutions (Talvi and Vegh 2005).

Financial development-proxied by the credit-to-GDP ratio: a higher level of financial development positively influences the ability of the government to borrow during downturns, and therefore it is expected to increase fiscal counter-cyclicality (Aghion and Marinescu 2008).

Trade openness-proxied by ratio of total exports and imports in GDP: more open economies tends to be more exposed to external shocks and therefore may use more actively fiscal policies in order to provide stabilization (Rodrik 1998; Lane 2003).

Capital account openness-proxied by the Chinn-Ito index of capital account openness: foreign capital to is likely to flow in (out) during expansions (recessions), therefore increasing the cost of financing countercyclical fiscal policies (Aghion and Marinescu 2008).

Government size-proxied by government expenditure-to-GDP ratio: as discussed in Fatas and Mihov, (2013) and Debrun and Kapoor (2011), government size can be considered as a proxy of fiscal counter-cyclicality under the assumption of unitary elasticity of taxes to GDP. Therefore, it is expected that fiscal counter-cyclicality tends to be a positive function of the size of the government.

Financial crises-based on the Leaven and Valencia (2010) dataset: the effect of financial crises on fiscal counter-cyclicality is ambiguous a priori. On the one hand, governments would be willing to run expansionary fiscal policies to offset the contractionary effects of the crises. On the other hand, the cost of financing countercyclical fiscal policies may increase during crises, particularly in countries with high debt levels.

Political variables:

Constraints on the executive: the main variables used are those proposed by Acemoglu et al. (2013) and Fatas and Mihov (2013). The first (constraints) captures potential veto points on the decisions of the executive. The second (polconv) captures not only institutional characteristics in the country but also political outcomes as its value is adjusted when, for example, the president and the legislature are member of the same party. In addition, we use dummies for the presence of expenditure, taxes and debt rules. As documented by Fatas and Mihov (2013), constraints on the executive are likely to reduce spending volatility and positively influence fiscal stabilization.

Elections-based on dummies for the occurrence of executive and legislative elections: during elections politicians may be tempted to change spending and taxes for electoral reasons and not necessarily for macroeconomic stabilization purposes (Drazen 2000; Persson and Tabellini 2000).

Other political variables: margin of majority, proportional representations and parliamentary regimes.

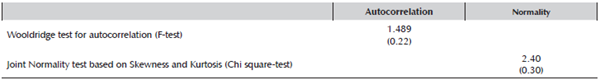

Since the dependent variable in equation (4) is based on estimates, the regression residuals can be thought of as having two components. The first component is sampling error (the difference between the true value of the dependent variable and its estimated value). The second component is the random shock that would have been obtained even if the dependent variable was observed directly as opposed to estimated. This would lead to an increase in the standard deviation of the estimates, which would lower the t-statistics. This means that any correction to the presence of this un-measurable error term will increase the significance of our estimates. To address this issue, equation is estimated using Weighted Least Squares (WLS). Specifically, the WLS estimator assumes that the errors  in equation (1) are distributed as

in equation (1) are distributed as  where sit are the estimated standard deviations of the fiscal counter-cyclicality coefficient for each country i, and

where sit are the estimated standard deviations of the fiscal counter-cyclicality coefficient for each country i, and  is an unknown parameter that is estimated in the second-stage regression. Finally, in order to reduce reverse causality, all the macroeconomic variables enter the specification with one lag.8

is an unknown parameter that is estimated in the second-stage regression. Finally, in order to reduce reverse causality, all the macroeconomic variables enter the specification with one lag.8

3.2 Results

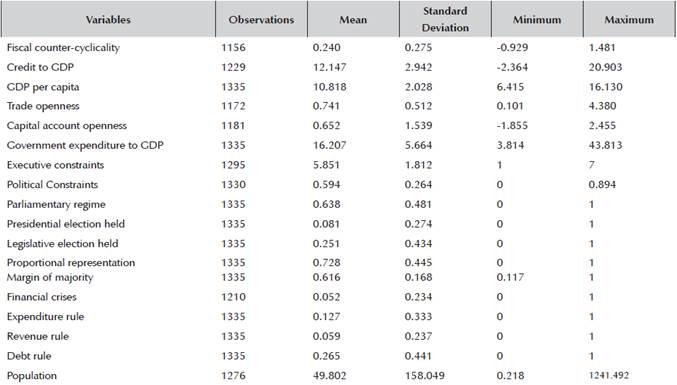

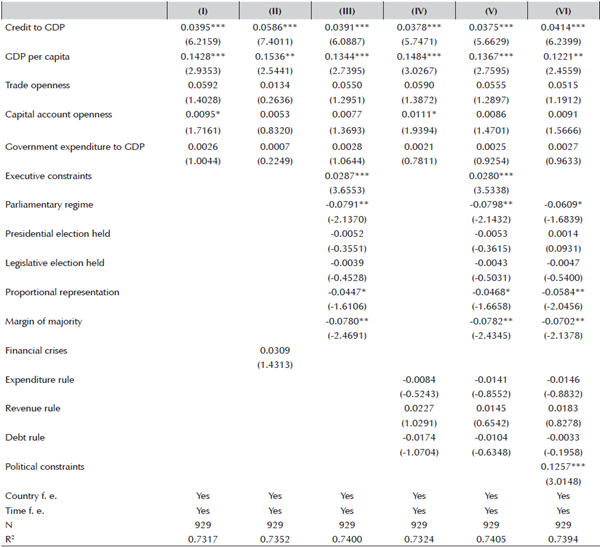

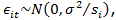

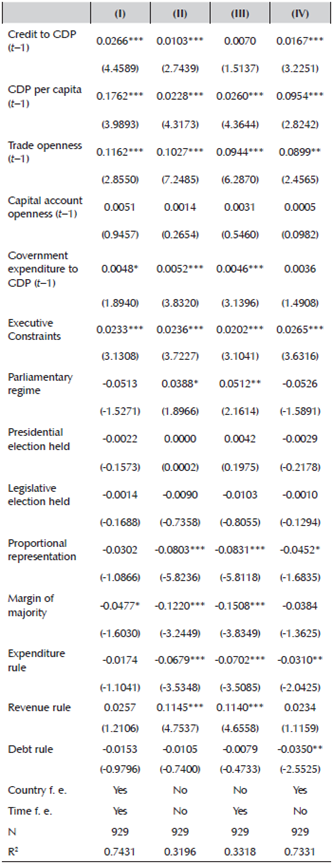

Table 1 presents the results obtained by estimating equation (4) using different econometric specifications. The coefficients associated with the various determinants typically exhibit the expected sign and confirm the conjectures discussed above.

Table 1 The determinants of fiscal counter-cyclicality

Note: Results obtained by estimating equation (4). t-statistics in parentheses based on clustered robust standard errors. ***, **, * denote significance at 1,5,10 percent level, respectively.

Source: Authors’ calculations.

Starting with the set of macroeconomic variables, we find that fiscal counter-cyclicality is robustly and positively associated with the level of financial development, with an increase of 10 percentage points in the credit-to-GDP ratio increasing the degree of fiscal counter-cyclicality by about 0.2-0.3 (i.e. by about – -1 standard deviation). We also find that more developed and open to trade economies tend to have a larger degree of fiscal counter-cyclicality. Similarly, countries with larger government are also able to provide more stabilization, even though the magnitude is not economically significant: an increase of 10 percentage points in the government expenditure-to-GDP ratio increases fiscal counter-cyclicality only by about 0.05. Finally, we find that fiscal counter-cyclicality does not increase during financial crises once other macroeconomic variables are controlled for.9

Looking at the political variables, we find that constraints on the executive (constraint and polconv) are robustly and significantly associated with fiscal countercyclicality. The results are consistent with the evidence provided in Fatas and Mihov (2013) and Lane (2003), who find that more constraints on the executive tend to reduce government spending volatility and positively influence overall fiscal stabilization. In contrast, all the other political variables, as well as dummies for fiscal rules, are not statistically significant.

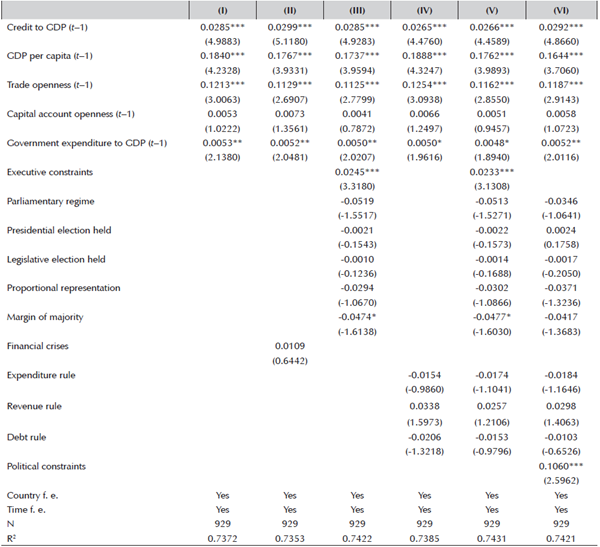

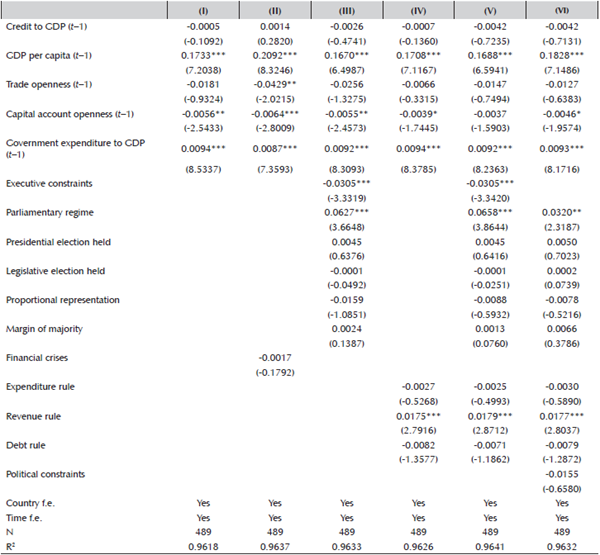

At the same time, some of these covariates tend to have different effects across country groups (Table 2 and 3). For example, while trade and capital account openness are negatively correlated with fiscal counter-cyclicality in advanced economies (as found by Aghion and Marinescu 20008), they are positively associated with fiscal counter-cyclicality in emerging market economies. Similarly, government size tends to have larger effect in advanced than in merging market economies, while the opposite is true for financial development.

Table 2 The determinants of fiscal stabilization - Advanced Economies

Note: Results obtained by estimating equation (4). t-statistics in parentheses based on clustered robust standard errors. ***, **, * denote significance at 1,5,10 percent level, respectively.

Source: Authors’ calculations.

Table 3 The determinants of fiscal stabilization - Non-Advanced Economies

Note: Results obtained by estimating equation (4). t-statistics in parentheses based on clustered robust standard errors. ***, **, * denote significance at 1,5,10 percent level, respectively.

Source: Authors’ calculations.

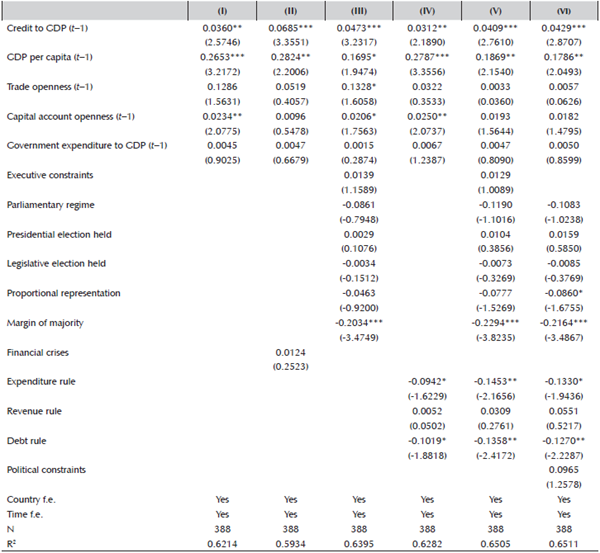

As a robustness check, we replicated the results for the full specification by alternatively excluding country and/or time fixed effects. The results reported in Table 4 confirm the statistical significance of the macroeconomic variables. In addition, while constraints on the executive remain statistically significant across all specifications, we also find that some of the political variables that were not significant before in the baseline regression now become significant when country- and/or time-fixed effects are omitted. In particular, both proportional representation and expenditure rules turn out to be negatively and statistically significantly associated with fiscal counter-cyclicality across the various specifications II-IV.

Table 4 Determinants of Fiscal counter-cyclicality, alternative specifications

Note: Results obtained by estimating equation (4). t-statistics in parentheses based on clustered robust standard errors. ***, **, * denote significance at 1,5,10 percent level, respectively.

Source: Authors’ calculations.

4. Effects of Fiscal Stabilization

4.1 Empirical Methodology

This section examines the effect of fiscal counter-cyclicalityon output voliatility. For this purpose, the following regression is estimated based on a balanced sample of 61 countries for which we have estimates of fiscal counter-cyclicalityfor at least 20 years:

Where  is the measure of fiscal counter-cyclicality estimated in the previous section for country i at time t;

is the measure of fiscal counter-cyclicality estimated in the previous section for country i at time t;  are country-fixed effects to capture unobserved heterogeneity across countries, and time-unvarying factors such a geographical variables which may affect the degree of fiscal counter-cyclicality and output volatility;

are country-fixed effects to capture unobserved heterogeneity across countries, and time-unvarying factors such a geographical variables which may affect the degree of fiscal counter-cyclicality and output volatility;  are time-fixed effects to control for global shocks.10

are time-fixed effects to control for global shocks.10

denotes output volatility-measured by the absolute value of output gap- in country i at time t. The reason we use as baseline the absolute deviation of output gap is that this measures is available at yearly frequency and therefore allows to maximize the number of observations in our sample. To check the robustness of the results, we look at alternative measures typically used in the literature such as the standard deviation of the output gap or GDP growth. However, a problem with these measures in specification at yearly frequency is that they yield errors that are serially correlated within countries. We mitigate this concern when we consider 5-year non-overlapping panels.

denotes output volatility-measured by the absolute value of output gap- in country i at time t. The reason we use as baseline the absolute deviation of output gap is that this measures is available at yearly frequency and therefore allows to maximize the number of observations in our sample. To check the robustness of the results, we look at alternative measures typically used in the literature such as the standard deviation of the output gap or GDP growth. However, a problem with these measures in specification at yearly frequency is that they yield errors that are serially correlated within countries. We mitigate this concern when we consider 5-year non-overlapping panels.

In order to reduce endogeneity due to omitted variables that may simultaneously affect output volatility and fiscal stabilization, we include in the specification a set of control variables  that have been found in the literature and in the previous section to be relevant: (i) trade openness; (ii) capital account openness; (iii) credit-to-GDP ratio; (iv) GDP per capita; (v) GDP growth; (vi) population; and (vii) government size. Moreover, all the macroeconomic variables enter the specification with one lag to minimize reverse causality. Equation (5) is estimated by Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) with robust clustered standard errors.

that have been found in the literature and in the previous section to be relevant: (i) trade openness; (ii) capital account openness; (iii) credit-to-GDP ratio; (iv) GDP per capita; (v) GDP growth; (vi) population; and (vii) government size. Moreover, all the macroeconomic variables enter the specification with one lag to minimize reverse causality. Equation (5) is estimated by Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) with robust clustered standard errors.

4.2 Results

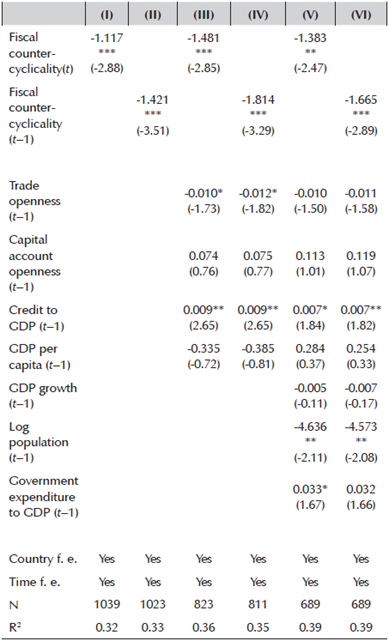

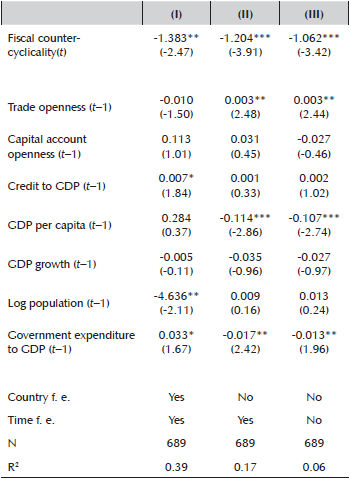

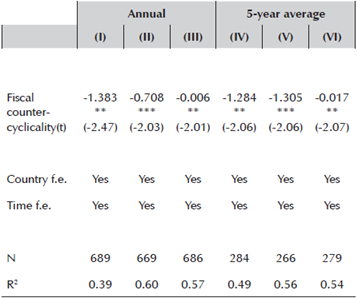

We start with a parsimonious specification of equation (5), using only country- and time-fixed effects as control variables. The results reported in Column I of Table 5 suggest that fiscal counter-cyclicality reduces output volatility. In particular, results suggest that an increase of 0.5 in our measure of fiscal counter-cyclicality (about 2 standard deviations) reduces output volatility by about ½ percentage point. In order to limit reverse causality, we reestimate this specification using the lag of fiscal countercyclicality. The results reported in Column II of Table 5 are similar and not statistically significantly different. Results are robust when the controls variables discussed above are included in the specification (Columns III-VI of Table 5), with that the effect of fiscal counter-cyclicality actually increasing, even though differences with respect to baseline estimates are not statistically significant. Among the control variables, we find that credit-to-GDP is positively associated with output volatility; while larger countries tend to be characterized by lower output volatility (this result is consistent with Furceri and Karras 2007). Interestingly, some of the variables such as trade openness, GDP per capita and government size-which are typically found to be associated with output volatility in cross-countries studies (for example, Fatas and Mihov 2001; Debrun and Kapoor 2011)-are not statistically significant in our case. The reason for this relates with the inclusion of country-fixed effects which purge most of their variability. Indeed, they turn out to be significant when equation (5) is re-estimated by excluding country fixed effects (Columns II-III of Table 6).

Table 5 The effect of fiscal counter-cyclicality on output volatility

Note: Output volatility measured as the absolute value of the output gap. Results obtained by estimating equation (5). t-statistics in parentheses based on clustered robust standard errors. ***, **, * denote significance at 1,5,10 percent level, respectively.

Source: Authors’ calculations.

Table 6 The effect of fiscal counter-cyclicality on output volatility, alternative specifications

Note: Output volatility measured as the absolute value of the output gap. Results obtained by estimating equation (5). t-statistics in parentheses based on clustered robust standard errors. ***, **, * denote significance at 1,5,10 percent level, respectively.

Source: Authors’ calculations.

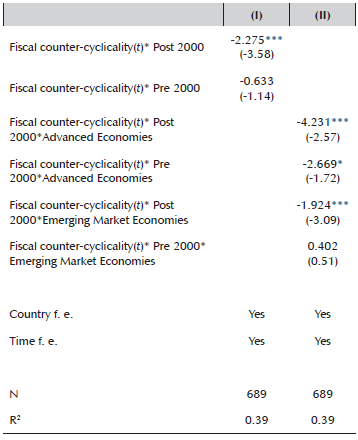

To account for the possibility that the relation between fiscal counter-cyclicality and output volatility has changed over time, we extend equation (5) by interacting the measure of fiscal counter-cyclicality with dummies for pre- and post-2000s, respectively:

The results obtained estimating equation (6) indeed suggests that the effect of fiscal counter-cyclicality on output volatility has increased over time (Column I, Table 5). Moreover, looking at the effect in the pre- and post-2000s periods and between advanced and emerging market economies, it seems that most of the increasing effect of fiscal counter-cyclicality on output volatility stems from the increase in fiscal counter-cyclicality in emerging market economies in the 2000s (Column II, Table 7). These results are consistent with the increase in the fiscal counter-cyclicality coefficient observed in many countries, particularly in emerging markets since the 2000s (Figure 1).11

Table 7 The effect of fiscal counter-cyclicality on output volatility, across time and country samples

Note: Measure I= absolute value of the output gap; Measure II= standard deviation of the output gap on a five-year window; Measure III= standard deviation of GDP growth on a five-year window. Results obtained by estimating equation (6). t-statistics in paren theses based on clustered robust standard errors. ***, **, * denote significance at 1,5,10 percent level, respectively.

Source: Authors’ calculations.

Robustness checks

To check the robustness of our results we re-estimated equation (5) using alternative measures of output volatility: (i) the standard deviation of the output gap computed over a five-year rolling window; (ii) the standard deviation of GDP growth computed on a five-year rolling window.12 The results presented in Columns I-III of Table 5, confirm that the fiscal counter-cyclicality reduces output volatility. In addition, the results are also robust when we estimate equation (5) on a five-year panel dataset using standard deviations computed on non-overlapping five-year windows.

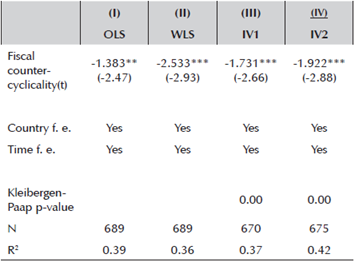

Given that out measure of fiscal counter-cyclicality is based on estimates, we further check the robustness of our results by estimating equation (5) with WLS, giving more weights to observations for which the degree of fiscal counter-cyclicality is estimated more precisely. This procedure yields a larger effect of fiscal counter-cyclicality on output volatility (Column II, Table 8). In particular, an increase of 0.5 (about 1 standard deviation) reduces output volatility by about 1 percentage point.

Table 8.The effect of fiscal counter-cyclicality on output volatility,alternative measures and data frequency

Note: Measure I= absolute value of the output gap; Measure II= standard deviation of the output gap on a five-year window; Measure III= standard deviation of GDP growth on a five-year window. Results obtained by estimating equation (5). t-statistics in parentheses based on clustered robust standard errors. ***, **, * denote significance at 1,5,10 percent level, respectively.

Source: Authors’ calculations.

A concern estimating equation (5) using OLS is that the results may be subject to reverse causality since governments concerned with output volatility could arguably adjust their fiscal behaviors to provide more stabilization. While in principle this issue is likely to not be relevant in our case, as our measure of fiscal counter-cyclicality depends on the past, we check the robustness of our results using an IV approach. Following Fatas and Mihov (2001, 2013), we select instruments capturing institutional and political characteristics of the countries likely to be correlated to our measure of fiscal counter-cyclicality but presumably not directly related to output volatility. Based on the results presented in the previous section, we alternatively use the constraints on the executive variables (constraint and polconv) as instruments. Another instrument considered is the lags of fiscal stabilization. The results reported in Column III-IV of Table 9 confirms that fiscal counter-cyclicality reduces output volatility, with the effect being slightly higher (although not statistically different) than the one obtained with OLS. In addition, the Kleibergen-Paap test confirms the validity of the instruments.

Table 9 The effect of fiscal counter-cyclicality on output volatility, alternative estimators

Note: Output volatility measured as the absolute value of the output gap. Results obtained by estimating equation (5). IV1= lagged fiscal counter-cyclicality and political constraints as instruments; IV2= lagged fiscal counter-cyclicality and polconv as instruments t-statistics in parentheses based on clustered robust standard errors. ***, **, * denote significance at 1,5,10 percent level, respectively.

Source: Authors’ calculations.

5. Conclusion and Policy Considerations

Several years after the Global Financial Crisis growth in many advanced and emerging market economies remains well below precrisis rates. Medium-term growth expectations have been steadily revised downward since 2011, highlighting uncertainties surrounding medium-term growth prospects (IMF, 2015). At the same time, public debt-to-GDP ratios have increased in many advanced and emerging market economies, reaching historical high levels in some of them. Against this background, how can fiscal policy contribute to higher medium-term growth?

Fiscal policy can influence medium-term growth through its support to macroeconomic stability. Using time-varying estimates of fiscal counter-cyclicality the paper find that fiscal policy by acting counter-cyclically can significantly reduce output volatility. In particular, our results suggest that an increase of 0.5 in the coefficient of fiscal counter-cyclicality (about 2 standard deviations) reduces output volatility by about ½-1½ percentage points. Back-to-the-envelope calculations-based on Ramey and Ramey (1995) estimates-suggests that an increase of 0.5 in the coefficient of fiscal counter-cyclicality increases medium-term growth by about ¼-½ percentage point.

A key question is then how can fiscal counter-cyclicality be improved, particularly in countries with high debt-to-GDP levels? While a large body of the literature has typically found that government size is the main determinant of fiscal stabilization, the results presented in this paper suggest that other macroeconomic policies and political characteristics can affect fiscal counter-cyclicality for a given government size. In particular, our results suggest that in addition to political constraints, policies aimed at fostering financial deepening, the level of economic institutions (proxied by GDP per capita) and trade openness can significantly increase the stabilization role of fiscal policy.