1. Introduction

The agreements between the Colombian Government and the FARC, and the dialogs with the ELN, lead to thinking that in the medium term the armed conflict with the guerrilla groups will end and will be reduced substantially; thus constituting a potential peace scenario.

Peace agreement to be reached must be essential for social transformations in Colombia. This way, more than a goal reached, said agreements must be understood as starting points for the Colombian Society to seek civil, democratic and not armed alternatives to solve multiple and complex conflicts.

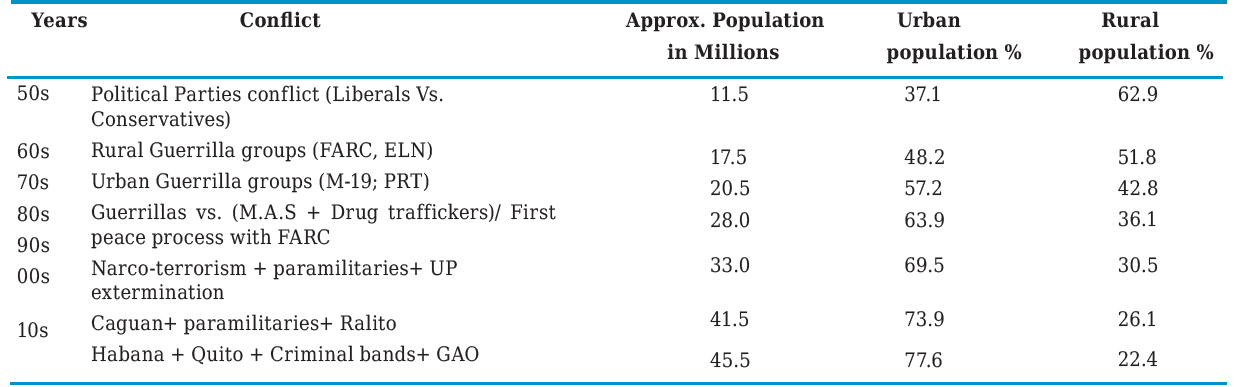

A schematic and short view on conflict in Colombia allows to see the importance of re-thinking the Business-Society relationship in pro of peacebuilding. Table 1 presents a scheme of conflict(s) in Colombia.

Table 1 Evolution of conflict in Colombia

Source: DANE- National Center of Historic Memory (CNMH, 2013)- FIP (2014)- National newspapers.

Abstracting the XIX century conflict, Colombia has been characterized by being a territory in conflict since the 1950s decade of the XX century. Political violence between liberals and conservatives during the 1950s promoted a socially, economically, culturally and of course politically fractured territory which deteriorated possibilities for greater and better development. The constitution of the National Front (political pact) legitimated an imperfect peace that fueled subsequent violence in Colombia. During the 1960s and 1970s conflict resurges with the emergence of Marxist-Leninist guerrillas which rose in arms against the State, bringing about new limitations to the country’s development. And in the 1980s the conflict is reduced by the emergence of drug-trafficking cartels, which in the 1990s led to the consolidation of paramilitary groups. During the 1980s and 1990s the first reconciliation processes with guerrilla groups took place; some failed (FARC) and other were successful (M19). Nevertheless, appearing paramilitary terrorism by the end of the 1980s made a peace environment impossible as requisite for balanced development. Yet, at the beginning of the XXI century doors opened for a reintegration process of paramilitary groups which, although imperfect, and subsequent political avatars, lead to a broader exercise of reconciliation with the FARC and ELN guerrillas, with proposals of deep adjustments to the model of development. Warning that the duality in terms of development between rural and urban Colombia creates different “speeds” and characteristics in the Business-Society relationship is not to spare. And even though is clear that to date Colombia is not yet a peaceful territory, it is still facing complex issues regarding criminal violence (BACRIM-GAO), even if it’s in the middle of consolidating processes of paramilitary reincorporation and reconciliation with guerrilla groups. Such political situation makes Colombia a territory bearing “Buffer Zone” characteristics (in transit from conflict to post-conflict) (Forrer and Katsos, 2015), which forces the re-thinking of the development model and the proposing of a renewed Company-State relationship.

In other words, a transition towards peace requires reviewing the role of several actors. Within these, there’s one in particular, the company. Company understood as an organization with social, political, environmental and ethical responsibilities (Berdal and Mousavizadeh, 2010).

Throughout the last few years private companies operating in Colombia have experienced “pressure” to disclose ever more information about their management, especially by two ways. The first one is the financial information contained in accounting reports elaborated under international accounting guidelines, and the second one, the one relevant to this study, is the disclosing of grouped information under the name of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) (Orozco, Acevedo, and Acevedo, 2013).

CSR information becomes a system of communication between a company and its environment insomuch that it includes economic, social and environmental variables. In principle, it is by means of this information that a company accounts to society for the effects it has produced, not only regarding shareholders but stakeholders, which may incise and even determine a company’s failure or success. Hence, CSR information becomes a vital input in reading the role of a company in the transformations it has produce or could produce on its environment (D’Amato Herrera, 2013). In the last decade it’s ever more frequent for large companies operating in Colombia to disclose CSR information, especially under the Global Reporting Initiative logic (GRI) (Gómez-Villegas and Quintanilla, 2012).

Subsequently, considering that Colombia to date may be characterized a post-conflict territory or in transit to it, and that companies must play a vital role in this process, the present work looks for hints to understand if the main CSR practices and the reports generated by companies could be an instrument or antecedent to Pro-Peace activities (Guáqueta, 2006; Kolk and Lenfant, 2015; Oetzel, Westermann, Koerber, Fort and Rivera, 2010). In search for empirical evidence a qualitative and exploratory scope study was carried out, which employed as instrument interviews to companies and associations focused on performing or monitoring Sustainability Memoirs under the GRI criteria.

This text has been structured into five sections, starting by this introduction. Secondly, the theoretical framework focused on the relationship between business and peace will be developed. In the third section, the methodology will be detailed. A fourth section will present and discuss field work results; this paper finalizes by drawing some conclusions and identifying future lines of research.

2. Theoretical framework

The business-peace relationship has been a field of study by disciplines such as political science, international relationships, sociology and more recently management (Ford, 2015; Forrer and Katsos 2015; Kolk and Lefant, 2015; Nelson, 2000; Oetzel et al., 2010). It has been stablished that there is a complex interdependence between corporate behavior and the resolving or maintining of conflicts (Fort and Schipani, 2007), and from the beginnings of 2000 it’s been studied how companies react strategically before their stakeholders in environments of violent conflicts (Dunfee and Fort, 2003). Of course, the new literature’s field work is centered around conflict or post-conflict zones such as Nigeria, Congo, Sudan, Guatemala, El Salvador, Colombia and Sub-Saharan Africa or the Middle East (Palestine-Israel) (Getz and Oetzel, 2009; Jiménez Peña, 2014; Kidder, 2006; Kolk and Lenfant, 2015; Madichie and Madichie, 2016; Nwagbara, 2014; Rettberg, 2007; Westermann-Behaylo, 2009).

The literature on management has focused on understanding the rinks linked to companies’ strategic actions in violent contexts and how to attenuate them (Delios and Henisz, 2003; Dunning 1998; Oetzel and Getz, 2012). Diverse aspects were examined regarding the involvement of companies in contexts of conflict and the factors they must take into consideration in developing new businesses. From this perspective, an important component of said analysis has been linked to the development of diplomacy theory and international relationships. The former has been focused on the macro-dimensional analysis of the effects of carrying out businesses on peacebuilding; the above as compliment to classical literature on international business, which has centered on the micro-dimensional analysis of opportunities and capabilities held by businesses in conflicted territories (Haufler, 2015). Corporate actions seen from a macro-level or micro-level for peacebuilding are set as a core business capability. Such capability contributes to preserving and accumulating an organization´s assest, its groups of interest´s wellbeing and accessing markets by exploiting a reputation of seeking what is fair (Saner et al., 2000; Steger, 2003).

Literature on business and peace changed its focus of understanding what the risks are for companies in conflicted environments by inquiring about the role of the private sector in resolving the conflict. Particularly, it became interested in understanding how have companies contributed to specific mutations of conflicted territories and the risks in said processes (Guáqueta, 2006; Katsos and Forrer 2014; Kolk and Lefant, 2015; Rettberg y Rivas, 2012).

These analyses have been guided by the questions, do companies have determining roles in conflicted territories? What are the strategies to contribute to overcome or lessen conflict? (Oetzel et al., 2010; Oetzel and Getz, 2012). These questions do not only accept the private sector playing a determining role in national and international scale conflicts, but it also presupposes that specific actions could be articulated (Pro-Peace practices) in order to positively influence achieving peace (Dunfee and Fort, 2003). Namely, companies may contribute to peace in scenarios of conflict or transition territories- Buffer Zone- (Forrer and Katsos, 2015).

This literature supports the proposition that companies that seek to overcome conflict offer better opportunities for conflicted territories. As a matter of fact, in conflicted, post-conflict or Buffer Zone contexts a company may generate initiatives supplying material and immaterial resources that create better conditions for conflict overcoming, or offering better territorial balance through alliances and forming social fabric (Abramov, 2009; Katsos and Forrer, 2014; Oetzel et al., 2010).

2.1 Business and peace in Colombia

Taking into account the literature on business and peace, and Colombia’s conjuncture of a possible post-conflict scenario (Buffer Zone), it is relevant to formulate the following question: how is companies’ role articulated with a peace scenario?

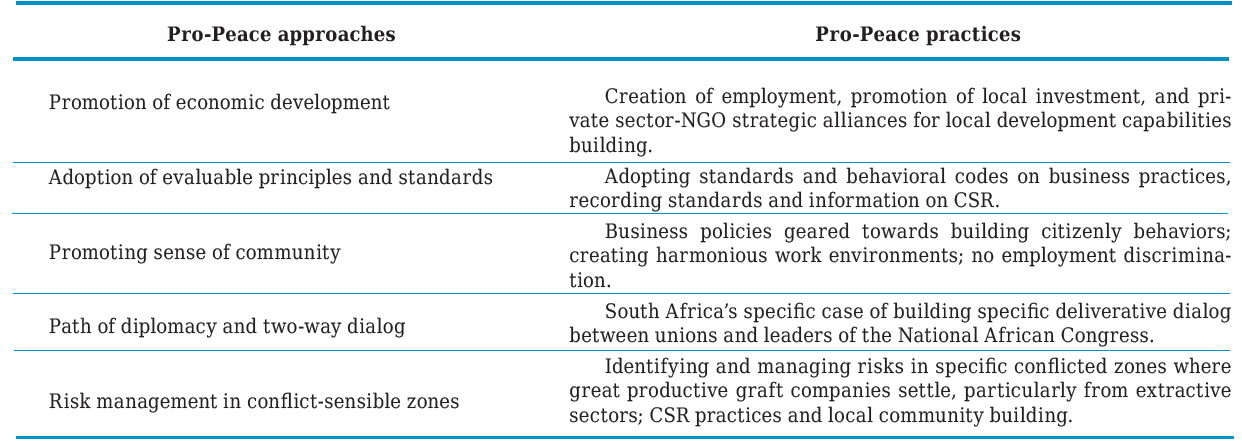

Possible answers may be generated by considering a set of Pro-Peace approaches where companies are the relevant actor (Oetzel et al., 2010; Oetzel and Getz, 2012) (Table 2).

In Colombia, Pro-Peace business activities, within a complex armed conflict scenario, has been characterized by practices that fall within each one of the approaches proposed by Oetzel et al. (2010) . For instance, large companies in Colombia have committed to programs related to promoting economic development. Particularly, with the generation of employment for the victims and ex-combatants, or the building of endogenous capabilities for local development based on the offer of education, health and promoting of entrepreneurial productive projects. Likewise, large companies have adopted management models with inclusive policies for human resources and the promotion of citizenly behaviors. Throughout different stages conflict negotiation since the mid-1980s, businessmen have participated as interlocutors to armed groups. And large companies of extractive nature have adopted robust risk management models when settling in armed conflict territories and they promote rapprochement to local communities in order to facilitate their operation. All these Pro-Peace approaches and their associated practices have been subject of study and critic; see, for instance, works by Rettberg (2003, 2006) , FIP (2012), Peña (2014) and at a broader frame of analysis Garay, Salcedo-Albarán and de León-Beltrán (2009).

What is relevant for this work, and considering Pro-Peace approaches set forth by Oetzel et al., (2010), is that Colombia has configured more clearly and rapidly approach number two termed “adoption of principles and evaluable standards” (Table 2). Conceptual discussion about this Pro-Peace approach may be broaden in Getz (1990), Emmelhainz and Adams (1999), Van Tulder and Kolk (2001), Kolk and Van Tulder (2002), or Steelman and Rivera (2006).As a matter of fact, a current of the literature on business and peace explores how standards and social certification systems generate favorable conditions for companies to be able to consolidate Pro-Peace practices (Kolk and Lefant, 2015; Rettberg and Rivas, 2012).

Despite its condition as a country suffering through an armed conflict, Colombia despite its status as a country in armed conflict has been building a modern urban economy, and rural economies with a strong incidence of extractive companies. Exposing Colombia’s economy to international markets at the beginning of the 1990s allowed it to be referenced competitively, and particularly the modern productive apparatus adopted quality standards as a natural way to penetrate and acceptance in international markets. In this regard, the ISO 9000 became a pioneer standard for Colombian companies, fruit of specific public certification promoting. This standard gave way to adopting management models focused on quality and subsequently to adopting other standards of the ISO family such as ISO 14.000 (environment) or ISO 26.000 (CSR). In sum, the sense of assurance and adoption of behavioral codes derived from the norms’ ruling principles became embedded in corporate management as a key element of modernity and business competitiveness.

Adopting evaluable principles and standards and their relationship with peace is proposed as a working thesis in Colombia. Guáqueta (2006), during an exploratory exercise on the Business-Peace relationship, argued that Colombian companies traditionally indifferent to the “rural” armed conflict were pressured by the alternative of dialog with insurgents, when the escalation of violence by the end of the 1990s “touched” the “normal” running of their businesses. In this context, the business class found an answer to its hostile environment in management focused on CSR. In other words, to Guáqueta (2006) a Pro-Peace approach based on evaluable CSR principles and standards determined a systematic rapprochement to the Business-Peace relationship.

On the other hand, by the end of the 1990s Colombia’s business class became pressured by escalating violence which forced it to rethink the Business-Peace relationship, and in searching for risk management found a response to hostile environments in CSR management models. Companies found in the principles of the Global Pact of the United Nations from 2000, in the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) at the end of the 1990s, and more recently in the ISO 26.000 from 2010 tools for standardized reporting and confirmation of behavioral codes guided by CSR principles. The Business-Peace relationship tightened by the end of the 1990s when companies bet on an approach of adopting evaluable CSR principles and standards (approach number two according to Oetzel et al. 2010).

The long and short, the thesis gearing this work is the Business-Peace relationship in Colombia being intensified by companies adopting principles and standards subject to appraisal, guided by CSR-focused management models.

3. Methodology

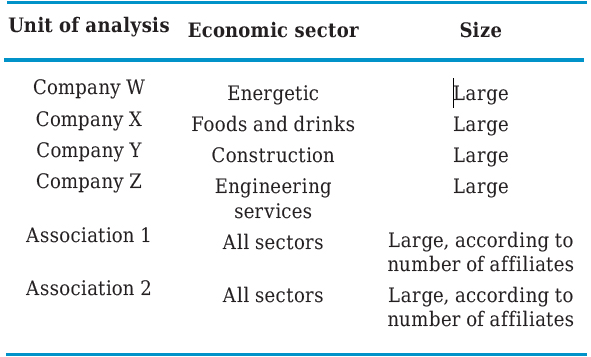

This work adopted a qualitative research approach with exploratory reach. An exercise of critical-interpretative analysis was employed as the technique of analysis by each author, in order to subsequently contrast in a triangulated manner each inference, argument, deduction and possible explanations arising from the critical-interpretative reading of the interviews. Four large companies were identified who would have been made visible leader regarding CSR affairs. To that end, we turned to the list of companies awarded with public CSR1 prices or acknowledgements. Moreover, 2 leading Associations in promoting CSR-focused and/or sustainability-focused management models were interviewed. The concept of sustainability assumes and CSR management approach based on the registry of practices under a triple helix model (Economic dimension, social dimension and environmental dimension). Interviews with a semi-structured guide were applied on management-level accountable for CSR-sustainability affairs. Table 3 illustrates the field work’s unit of analysis.

4. Results and discussion

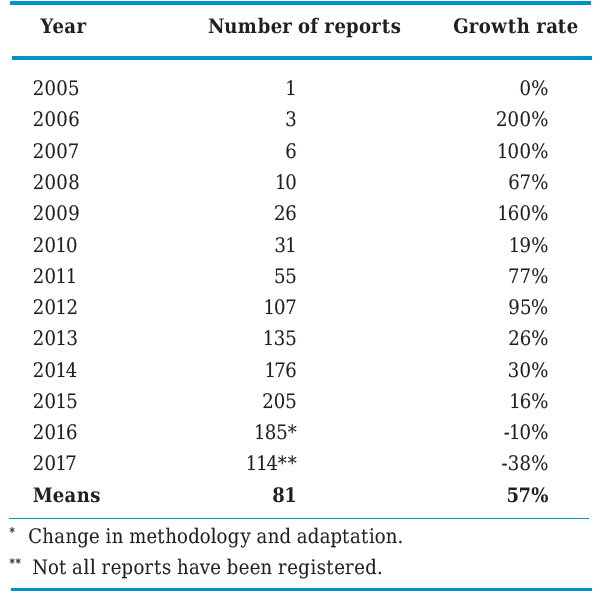

The first empirical fact describing major involvement of companies in Colombia with CSR-focused management models, and its implications with regarding standardization and appraisal affairs, would be the growing number of companies who have adopted the Global Reporting Initiative methodology (GRI). The adoption of the GRI methodology has increased since 2005 at an average rate of 57% (Table 4). The aforementioned is but a validating element that companies in Colombia have become involved in Pro-Pace Practices. The above in this writing’s thesis orientation, namely, that higher betting on CSR has implied an exercise of involvement by companies in the so-called Pro-Peace practices; this is for Colombia’s specific case, as it is deemed a Buffer Zone.

4.1 CSR concept evolution in Colombia

Initially, CSR conceptualization was inquired about and three key aspects were found: i) transiting from the concept of CSR to the concept sustainability (GRI); ii) the evolution of the CSR concept towards the Creating Shared Value (CSV) (Porter and Kramer, 2011) and iii) changes in CSR management privileging liaising with different actors.

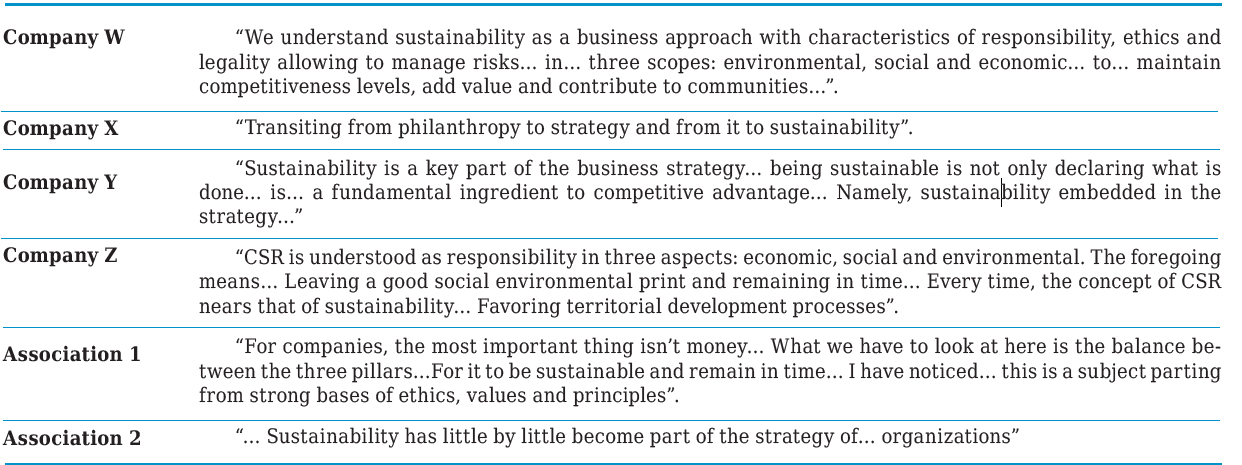

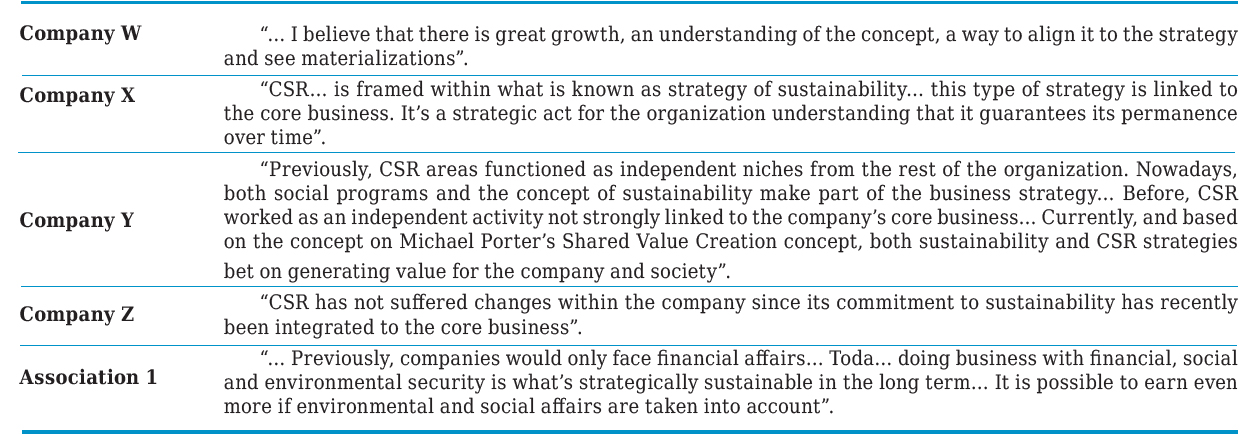

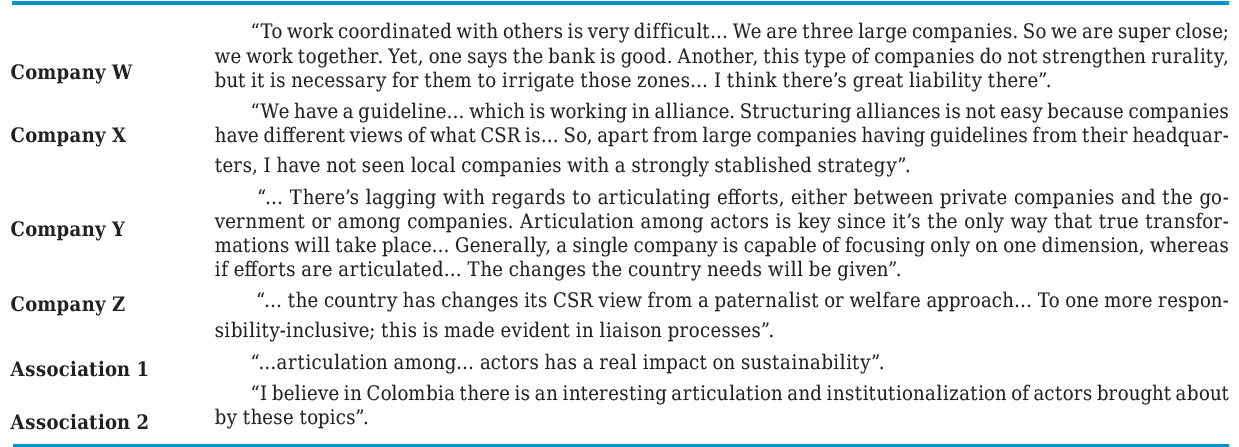

Table 5 verbalizes the CSR’s transit towards sustainability.

CSR is linked to the need for companies to be sustainable. Said realization suggests a qualitative jump by understanding CSR not as isolated actions for common good (philanthropy) but as a bet on economic, social and environmental equilibrium. There is a transition from owner-exclusive accountability to a CSR understanding where interests groups are acknowledged. For the Company Y its sustainability model has to do with three large components:

“1. Creation of economic value: because no company survives over time if it’s not profitable and does not generate value or profits for its shareholders. 2. Environmental print management: attempts to minimize impacts on the environment generated by industry with clearly defined objectives in the matter of quarries recovering, substituting fossil fuels with alternative fuels and water management. 3. Relationship with stakeholders (social component): regarding interest groups, the company’s priority would be its employees, especially with regards to health and safety. The most important goal is zero accidents and incidents. As such, the second stakeholder in range of importance would be communities neighboring the company’s operations. The company highlights that 100% of its operations count with community liaising plan. This is why the company engages in Neighbors Committees, which constitute spaces of dialog seeking to comprehend the needs of the community, and from them begin to create social projects according to the company’s strategy and the objectives it has traced”.

Table 6 verbalizes CSR evolution towards Creating Shared Value.

CSR was found to be directly linked to the core business. The foregoing means that CSR is conceived as articulated to the corporate strategy and not as an element isolated from strategic business goals. “CSR and sustainability in turn constitute the DNA of the company and for that reason it must be integrated as a strategic element of long-term planning” (Company X).

CSR in Colombia is evidenced to have imbricated in corporate strategy. For instance: “CSR… has been given specifically because CSR strategy came about completely defined with management indicators, with different stages of progress directly from London” (Company X). CSR applicability by large companies in Colombia obeys sustainability criteria inherent to the core of the business. In this regard has been given the “evolution in concepts such as philanthropy to strategic philanthropy, in order to move to CSR and now to the generation of shared value” (Company Y).

Finally, Table 7 verbalizes in CSR conceptualization the emphasis of liaising with actors.

Regarding CSR, even though “there are good intentions”, changes in CSR management are not immediately evident. The above in virtue of CSR being long-term and with its actors’ joint work. A reading of ethical foundations would say that:

“… the generalized idea that companies must act responsibly is ethically correct because it has repercussions on the fact that it creates added value; not everything has to be for the company to have added value from the economic standpoint. By the foregoing, it is ethically correct to consider companies to act as such, not only because it improves their image or because there’d be a return on investment but because it cannot continue to be in a country where a stand isn’t taken in favor of growth and development of vulnerable communities” (Company Z).

Even though there’s a bet on sustainability from a CSV vision (Porter and Kramer, 2011), the articulation of actors is still incipient. CSR and the bet on sustainability require commitment from different groups of interest… “CSR management requires integrated articulation of actors if we as a society aspire to build social fabric” (Company X).

To sum up, the concept of CSR has evolved in three regards. Firstly, nowadays it’s more comprehensive for companies to speak of sustainability and in that regard the GRI methodology and elaboration of Sustainability Memoirs are better assumed. Secondly, the CSR concept has gone from a limited reference to philanthropy as an isolated business practice to a conception where CSR must be imbricated in the company’s competitive strategy (CSV). And thirdly, CSR discourse has emphasized the intense and tough challenge of creating value amid hard work to build up relationships.

4.2 Pro-Peace Practices in Colombia

Framed in a context of internal conflict, companies in Colombia have found in CSR standards and their associated behavioral codes a way to understand and become involved with their complex and violent environment. Specifically, pragmatic aspects arising from the registry of companies’ activities or social facts in sustainability reports has led them not only to “handle” violent environments, but has changed their sense of reaction and adaptation for proactive acting in function of a peaceful territory. Peace understood not as an ideal state but as task and rethinking of company’s function in environments with high risks of social and violent conflict.

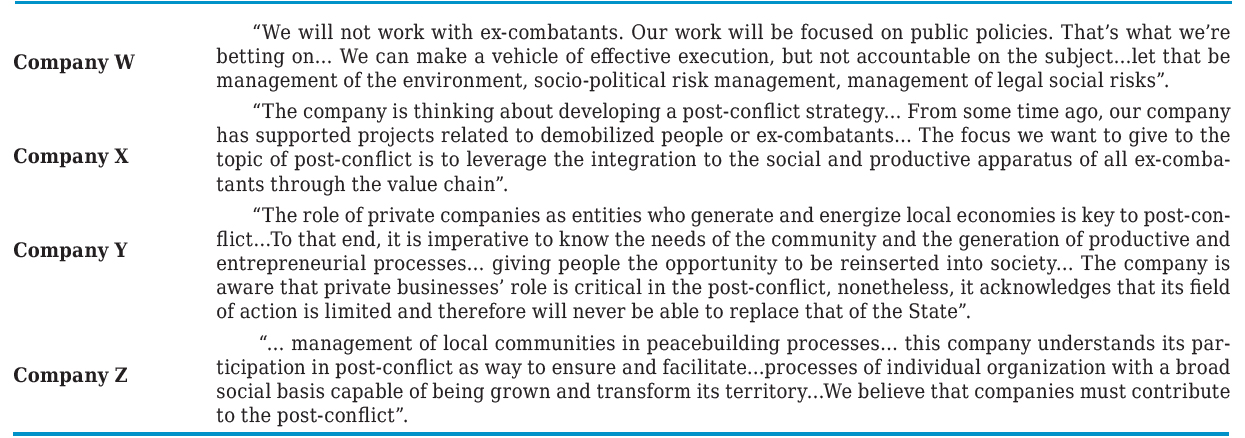

Table 8 accounts the company’s verbalization about its tasks in function of possible peace in Colombia.

Companies’ verbalization to the question about their involvement in post-conflict affairs makes four key aspects evident: i) companies understand their role within post-conflict or violent social environments is subsidiary or complimentary to the State’s role. In other words, political responsibility in the search for peace or to ameliorate violent conflicts is borne by the State, but a company must converge in territories as visible promotor of peace policies; ii) companies have incorporated the concept of risk management more clearly; risks beyond economic and financial affairs so as to include social, political and legal perils; iii) companies have assumed CSR as an economic value creating strategy, or at least that their social actions with a conflicted environment must be understood from the logic of value chains. In this regard, companies declare the importance of formulating projects, forming human capital and betting on entrepreneurship, and iv) companies have involved territory into their discourse. Namely, communities understood as stakeholders in the companies’ view are determined by their roots and territorial settlement, which implies acknowledging the communities’ explicit affectation by the conflict and the need to accompany it in rebuilding social fabric.

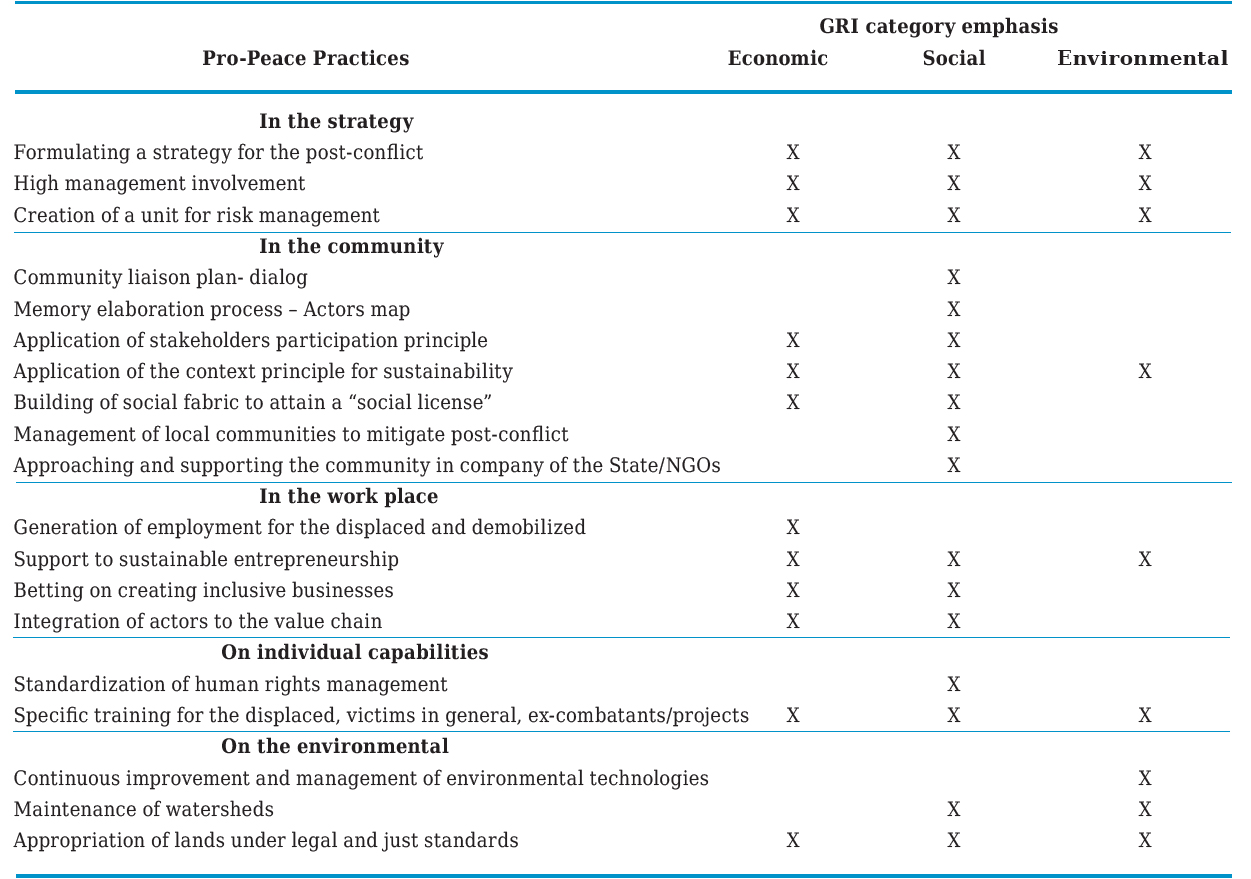

Finally, a field work reading was carried out with the purpose of scheming companies’ Pro-Peace practices. This exercise reinterpreted approaches and Pro-Peace practices identified in the literature (Table 2). Specifically, large companies in Colombia were considered to have bet on CSR standardizing through elaborating Sustainability Reports, and on the concept of sustainability implying the differentiation of CSR practices in three categories: economic, social and environmental. Specifically, Pro-Peace practices were divided into: i) fruit of the strategy; ii) with impact on the community; iii) with effects on the worker; iv) with effects on people’s development and the favoring of their human dignity; and v) practices impacting the environment. Table 9 presents the scheming of Pro-Peace Practices promoted in Colombia the four large companies interviewed.

In general, Pro-Peace practices contribute to developing more inclusive institutionalism, more and better spaces for dialog and participation of communities, as well as respect for human rights and better preservation of natural resources.

Firstly, Pro-Peace practices performed by companies are found to be articulated to the general strategy. CSR strategy conceived from Pro-Peace practices is linked to three dimensions of sustainability and responds to the direction of higher management. Plans or roadmaps are advanced in order to define actions in to face a peace of post-conflict scenario. The foregoing requires directives’ specific involvement and not as the isolated actions of a department. Risk and stakeholder management teams or units are shaped. In general, there is a change of hierarchy in the decision making scope when the company takes on a CSR strategy from the perspective of Pro-Peace practices.

Secondly, Pro-Peace practices highlight the need to think about business activities in the context of a territory, and particularly from the specificities of the community. Permanently managing relationships with communities becomes crucial, and in this vein communities appear as the epicenter of intervention actions by the company in the territory. A bet is placed on dialog and participation with actors; families and people within the territory are valid and imperative interlocutors, which is why a detailed mapping of actors (groups of interest) and their specific needs is important. Being accepted by communities within their territory becomes essential for companies; the need is acknowledged for a “social license” legitimating the company as an actor of the territory. The foregoing is understood by companies under constant contact and dialog with local and national government.

Pro-Peace practices, within the third group of action, plead for the improvement of working conditions and human and labor rights compliance. The possibility of integrating actors from the conflict into companies is a neuralgic topic which enables opening a path to reintegration to ex-combatants, victims or the displaced. There is a bet on social inclusion and the understanding that companies may contribute to local or regional balance during the post-conflict.

Fourthly, from an individual capabilities approach and with regards to human rights, it becomes clear that there’s a need to create opportunities for entrepreneurship and training. The company’s institutional frame, institutional documents and standardization of CSR have been strengthened. Specifically, that one regarding respect for human rights. Likewise, the company has contributed to developing agricultural, technical or technological skills, yet it has also bet on the development of citizen values and respect for human rights. The foregoing represents a key axis in the building of deliberative way and participative action particularly contributing to social fabric and a more inclusive public space.

Finally, the company has understood in Colombia Pro-Peace practices are tightly linked to adopting legal frames adequate for respecting and caring for the environment. The role of companies in a conflicted environment has led to following the environmental print and incorporating derived externalities into the value chain. The company has engaged in the specificity of watersheds and water management as a very specific case in Colombian conflict. The company has also understood crucial land management under legal and just conditions for countrymen and minorities found living in conflicted regions of low institutional presence. CSR strategy in a context of Pro-Peace practices has led to better understanding impacts on the environment and particularly those aspects associated to watersheds and land management, so expensive to the violent conflict in Colombia.

Pro-Peace practices in Colombia have been legitimized when recorded in companies’ Sustainability reports. As a set, these practices may be equated to those identified in the literature (Ford, 2015; Forrer and Katsos, 2015; Oetzel et al., 2010; Oetzel and Getz, 2012) and framed within economic development, building a sense of community, diplomacy, promotion of dialog and risk management; but particularly to those practices associated to the establishment of CSR principles and standards (Table 2). Specifically, the second approach to Pro-Peace practices).

5. Conclusions

Colombia may be characterized as a “Buffer Zone” country and a developing country specifically. Over 50 years of internal conflict with different actors, both from the extreme left and the extreme right, have fixated in people’s and companies’ minds an administration model focused on risk management. It could be thought that companies have gradually learned from a violent context in order to generate management adapted to the Colombian context.

Pro-Peace practices in Colombia, namely businessmen becoming involved in Colombia’s violent conflict, have been made more visible and have been promoted with greater vigor and relevance since companies have bet and learnt through models or certification or verification of administrative processes. This is exemplified from the adoption of the ISO 9.000 to the ISO 26.000 norms. Assuming these learning curves in Colombia, this research found that companies have become more aware about their productive doings in a conflicted business environment and violence; the foregoing since adopting strategies betting on putting CSR models into practice.

In other words, the thesis set forth in this work considering the comprehensive exercise by Guaqueta (2006) was supported by the empirical evidence found. It was supported in three key elements: i) Since the 1990s companies in Colombia have adopted administrative practices certification models, which at first instance sought to improve efficiency and quality but progressively became biased to models that deemed social value creating practices as sources of competitiveness. In short, companies evolved from ISO 9000 (quality) up to ISO 26000 (CSR) or other equivalent accountability models (GRI). Pro-Peace practices were promoted from the adoption of principles, behaviors and evaluable or verifiable standards; ii) companies evolved their CSR conception. These migrated from a philanthropy-centered approach towards a social value concept based in the idea of creating shared value (CSV), in Porter and Kramer (2011) vein, and in CSR’s broader conception of Sustainability when truly putting into practice a management model of relationships and community creation. Once again, Pro-Peace practices were promoted from the adoption of principles, behaviors and evaluable standards; and iii) from the year 2000, companies in Colombia have become internationalized in social practices certification models, particularly with the involvement of large companies in GRI sustainability models and associated to these with the behavioral guides of the United Nation’s Global Pact. In sum, Pro-Peace practices were promoted from the adoption of principles, behaviors, evaluable and verifiable standards.

Pro-Peace practices of Colombian companies have revealed particular aspects confirming the typology of practices identified in the literature (Oetzel et al., 2010; Oetzel and Getz, 2012). Firstly, Pro-Peace practices have permeated companies’ general strategy. In other words, Pro-Peace practices have acquired a high management status endorsing businesses’ bet on CSR management, and the being deemed as a source of competitiveness, by supposing that social facts must be imbricated in the conformation of the value chain. Secondly, Pro-Peace practices have made dynamic the imperative conception of a business environment determined by the constitution of community. Namely, Pro-Peace practices have highlighted the role of building relationships of trust with the community under the company’s need to find legitimacy in achieving a “social license”. Thirdly, Pro-Peace practices have understood that their relationship with the State or local governments is one of complementarity and respect given the scope of action and differentiation between corporate policies and public policies. From this perspective, companies have understood that creating employment and consolidating human capital in its local environment is a way to contribute to social justice and the community’s legitimacy. Finally, Pro-Peace practices have made evident that environmental sustainability of watersheds and land holding were considerably affected by the armed conflict. As such, Pro-Peace practices have prioritized environmental topics as a contribution to building a community environment with social, economic and environmental justice.

The lessons for business practices derive thereof findings in terms of the Pro-Peace practices identified. Namely, companies in Colombia have come a long way since adopting CSR models, and particularly when such models are biased towards business practices justified and supported by the literature from the recent company and peace field of study.

This study holds several limitations. Adopting a qualitative methodological approach implies a limitation associated with determining the theoretical sample. The former does not permit to highlight results as representative of business population in Colombia. The theoretical sample chosen for this study possesses a selection bias towards large companies, which are the one displaying a higher level of administrative modernization and those are the majority of companies who have bet on implementing models of business practices based on CSR (56% of companies report GRI in 2017). This study assumes a positivist perspective of analysis where the researcher remains neutral. For the kind of problem proposed by this study, this perspective is bet on validating theoretical frames, and in this vein valuable inputs of analysis are given. Nevertheless, the Business-Peace relationship, and particularly Pro-Peace practices in environments such as Colombia, require a hermeneutical perspective going beyond the data and coming close to the meaning of the practice within its context.

As future research lines we propose in-depth studies of Pro-Peace practices in Colombia from the conceptual framework of the Business-Peace relationship. Qualitative-end studies with hermeneutical perspective must be broadened, as well as proposing complex quantitative models explaining companies’ Pro-Peace behavior in Buffer Zone environments.

The need arises to deepen studies according to the typologies of Pro-Peace practices in Colombia, following the patterns found in the international scope. This is, those practices associated to local economic development, community sense building, promotion of corporate diplomacy and risk management understood beyond economic and financial perils. Moreover, it will be very important to differentiate between Pro-Peace practices as these occur in urban or rural contexts; to discriminate by sectors extractive and non- extractive of natural resources, and of course to understand the difference of Pro-Peace practices according to company size. And from a perspective opposed to this article’s positive outlook, possible Pro-War practices arising from Corporate Social irresponsibility (CSI) should be studied.

Finally, and as an academic challenge of magnitude, the consequences arising from possible peace agreements with the guerrillas must be studied in terms of modifying proactive business behaviors to peacebuilding in Buffer Zone territories. As such, for instance, Pro-Pace practices could be studied in function of the large components of the peace agreements with the guerrillas, specifically those practices promoting the better implementation of an integral rural reform, political participation, solutions to the problem of illicit drugs and compliance of victims’ rights, among others that might arise when implementing and countersigning those agreements (Jaramillo, 2015; OACP, 2016).