1. Introduction

The Colombian internal armed conflict corresponds to a complex phenomenon with a trajectory of more than 50 years -one of the longest at the international level- with devastating consequences for civil society, the private sector and the institutional framework of the State (Historical Memory Group, 2013, Calderón, 2016). According to the National Information Registry of the Victims Unit (2018) as of November 2018, nearly 8.8 million victims had been registered in the country. The most representative victimizing events are forced displacement (7.4 million), homicide (1 million), threat (399 thousand), enforced disappearance (171 thousand), loss of assets (114 thousand), among others.

Likewise, the internal armed conflict in Colombia has been characterized by the permanent political tension guided by the confrontations and the efforts of some governments in turn to access scenarios of dialogue and peace processes, which are based on the serious effects of conflicts armed (Echandía, 2000; Theidon, 2004; Álvarez and Rettberg, 2008; Wilches, 2010). The construction of peace corresponds to a legitimate option of the States, and at present, the country is going through a new and unprecedented stage on the signing of the Peace Agreement between the Government of Juan Manuel Santos and the FARC-EP guerrilla, subscribed in 2016 (Ríos, 2018).

Two years after the signing of the Agreement, one of the aspects that still cannot be precise or form is the way in which civil society and the private sector will participate in the construction of the so-called “stable and lasting peace”, despite the fact that in the same Agreement, and in its key points, it expresses the need to involve these two agents throughout the process. Private enterprise has always been considered a key element in the economic and social development of the territories where they carry out their corporate purpose (Murcio and Ángel, 2011), and in post-conflict scenarios such as the Colombian case, the business sector it can fulfill a leading role as long as it is linked to it from the strategies and public policies of the State, and the construction of articulated channels between the institutional offer and private support.

The company is a key player in an armed conflict, either by deepening its effects by omitting responsibilities or facilitating actions, or by being a subject of affectation (Prandi, 2010a, p.35). But also, in post-conflict scenarios the company plays a fundamental role given the responsibility it holds in the reconstruction of the social fabric opens the space to great challenges so that from its activities and operations it can favorably affect the generation of opportunities and conditions that are clear and precise. There is no doubt that good business practices are required that can favor society, especially those most affected by the war, but there is also a peaceful scenario marked by dialogue, cohesion, and healthy coexistence can have an impact positive in the performance of the companies, the development of productive projects, and the promotion of prosperous and sustainable businesses. Drucker (2002) points out that there can be no successful companies when society is in decline, therefore, the company not only has the opportunity but the obligation to seek mechanisms that help in the consolidation of peace and in the search for reliable, competitive, and safe markets.

Considering the above, the objective of this article is to analyze the role of the Colombian business sector in the post-conflict scenario and the construction of peace, based on the perceptions obtained from the analysis of the results obtained from a questionnaire on the subject, applied to 200 companies in the country that belong to the economic, commercial, services, manufacturing and financial sectors. In the article, the literature review is presented at the beginning, then the methodology and results of the study are described, and finally, the main conclusions are presented.

2. Literature review

2.1. The post-conflict scenario and the construction of peace

Talking about post-conflict and peacebuilding in Colombia is looking with hope at the present and the future of the new generations, because after 50 years of conflict the effects in terms of social and economic damages are still incalculable (Feldmann, 2008; Castro, Beristain, and Afonso, 2017). Once an agreement has been reached to end the conflict with the FARC-EP, a phase begins in which society must resolve the causes that gave rise to the armed confrontation and in which all the social actors establish new rules of the game facilitating the social cohesion. Post-conflict is the period in which all commitments are implemented in order to respond to each of the points that are considered priorities and necessary for the reconstruction of the social fabric, reconciliation, the achievement of justice and elimination of all the factors that have given way to confrontation. It begins with the cessation of hostilities between the parties (Rettberg, 2003, p. 17) and resolves the structural issues of society, guaranteeing the non-repetition of the conflict. It is a fundamental process in which the participation of the builders of peace, the postwar government, and civil society is required, among them the private companies (Barnett, Fang, and Zürcher, 2014).

In the face of the social and economic deterioration caused by the war, the task of reconciliation and peacebuilding requires multiple factors: the active participation of different players, a set of conditions to guarantee truth, justice and reparation for victims, guarantees for ex-combatants to return to civil and political life, public policies aimed at eliminating the situations that gave rise to the conflict, relevant institutional designs, among others. There is no doubt that a post-agreement process requires great efforts and extensive public investment, that is, it involves a long, continuous and coordinated task (Ugarriza, 2013, Herrera and Torres, 2005, Sacipa, 2005, Rettberg, 2005).

Peace after a conflict is often fragile, almost half of all civil wars are due to relapses in previous post-conflict stages, so post-conflict societies face two challenges: economic recovery and risk reduction. a recurring conflict (Collier and Söderbom, 2008). In order to solve these challenges, the effort of the State is not enough, but the decisive and articulated participation of the different actors of society are required through resources, ideas, and experiences (Garzón, 2003), acting ethically without discriminating to any recipient and seeking to claim equity and equality among human beings. This syllogism is called “construction of peace” and consists of a set of measures designed to strengthen social structures to consolidate peace, prevent the resumption of conflict, and deal with the mistakes committed, in that context, through justice and true (Binningsbø, Loyle, Gates, and Elster, 2012).

The processes of reconciliation and peacebuilding seek, among other things, to facilitate the victims and the ex-combatants themselves to be actively linked to civil and political life, which implies dignified conditions in work, housing, health, education, and other socio-economic rights. Obviously, it requires strong cooperation for the achievement of this social justice that serves as a basis for building peace. In this framework, companies play an essential role (González, 2016, Guáqueta, 2006, Esteve, 2011), since through their economic activity they generate jobs and redistribute wealth, and because of their capacity, they can contribute with projects and programs in the Framework of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR).

The construction of peace, according to Rettberg (2003), can be approached from three approaches: 1. Minimalist that seeks the repair of the damages caused by war such as the reconstruction of the destroyed infrastructure, 2. Maximalist that implies not only the end of the conflict but the establishment of necessary conditions to generate social development and eliminate the causes that caused their origin as poverty, inequality and exclusion, and 3. Intermediate or eclectic that begins before the cessation of hostilities and ends when society has overcome the damage caused, have learned to respect the new social rules, has healed wounds, and there is a widespread belief that new or remaining differences cannot fall on the violent conflict between the parties.

In any case, the three perspectives require determinant and coordinated strategies among social actors to eradicate the causes of confrontation and ensure that society accepts and respects the new social order, preventing differences of thought and social imaginaries from being the source of new clashes.

2.2. Private enterprise in the context of conflict and peacebuilding

The private sector recognizes that its contribution is fundamental to the complex process that implies the post-conflict and the construction of peace. However, not all entrepreneurs have clarity on how to effectively link to the process, so this paper explains the mechanisms necessary to empower themselves in the process and coordinate their efforts with the State and other national and international agents. As described in the studies of Prandi (2010)b, Montañés and Ramos (2012), among others, one of the main difficulties for companies to engage actively in post-conflict and peace-building processes is their scarcity. knowledge about international and national norms in Human Rights and International Humanitarian Law, as well as their low understanding of the relationships that arise between business, armed conflict, and post-conflict.

There are several theories to deal with the post-conflict and the construction of peace, among them the minimalist, maximalist and eclectic or intermediate. The first defends the idea of repairing the damage caused by the war, serving the victims and rebuilding the infrastructure, the second not only focuses on fixing the damages but also believes that it is necessary to rebuild the social structures and eliminate the causes of the conflict, and the third perspective is the eclectic one in which building peace means ceasing hostilities, healing individual and collective wounds, repairing the harms of war and making society learn to play and respect the new rules of the game, without Differences exacerbate the spirits and relapses in the conflict (Valencia, Gutiérrez, and Johansson, 2012, Rettberg, 2003).

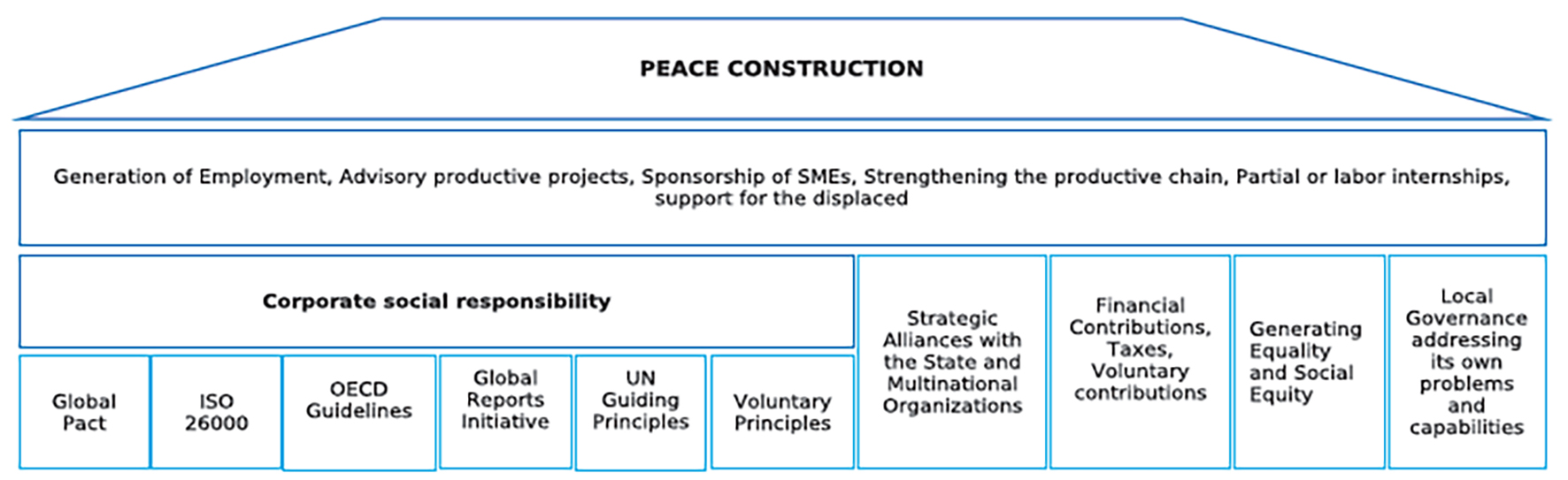

In any of these theories, the company has a fundamental role in the reconstruction of peace, through legal or organizational mechanisms such as 1. Financing, 2. Alliances with the State and national and international entities to consolidate resources and experiences, 3. The development of programs and actions of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), 4. Assuming responsibilities in the face of situations of inequality and social inequality and transforming their structures and actions to eliminate the causes that could give rise to violence, and 5) Governance in that local players assume their own realities, problems, and interpretations.

Several studies highlight the complex relationship between conflict, peace, and the economy (Guáqueta, 2006; González, 2016; Rettberg, 2008; Álvarez and Rettberg, 2008; Sanín, 2004). Such research accepts that economic factors at the global, regional, national and local levels can promote or discourage conflicts in many ways and, therefore, are central to establishing a durable and sustainable peace (Millar, 2016). Hence, private enterprise in a neoliberal economy like the Colombian one is a fundamental player of the post-conflict and the construction of peace.

The role of private enterprise in the armed conflict is subject to multiple studies and controversies. Some believe that their unequal behavior towards society generates greater escalation and intensity in the conflict, others consider that private companies, especially local ones, are key in the solution of society’s problems, due to their capacity to generate wealth and development, and a third category locates the company as an actor affected by the conflict.

Those who believe that the company is a key factor in deepening the conflict explain that illegal armed groups are financed through extortions or contributions from companies, in exchange for allowing performance and not affecting their infrastructure. They also explain that private enterprise is the main cause of conflicts due to power and wealth concentrated in a few (Swearingen, 2010) and favored by a half-democratic system that assures elites perpetuation in positions of power (Robinson, 2013).

From this interpretation, it is necessary to emphasize the need that all actors, both government and armed groups and unarmed, recognize the responsibilities that are faced with the armed conflict, because it is a key to achieve transit from a fractured society to a society that opts for dialogue, peaceful coexistence, respect for fundamental rights and respect for difference: “as demonstrated in the South American experience, by addressing these issues opens the way to build processes of reconciliation, reparation and memory “. (Sepúlveda, 2016, p. 524).

Another current identifies a potential role of the company in the construction of peace, especially the local one, as a generator of employment and entrepreneurship opportunities for people with less social possibilities due to their educational or economic level, the demobilized and victims of war (Prandi, 2010b). This approach arises from the perspective that defends a development characterized by the recognition of local potentialities and opportunities.

A third perspective is the company as an affected actor, in which it is obliged to pay extortions in exchange for not being the target of attacks on its infrastructure or its personnel, with the aggravating circumstance that the victim prefers not to report for fear of retaliation that may take illegal armed groups (National Association of Businessmen of Colombia, 2014).

In any of these perspectives, private enterprise is considered a key actor for the success of the post-conflict and the construction of peace, since its immense wealth and its capacity to generate great initiatives contribute to the creation of feasible scenarios for the economic development of the country and the social stability, understanding that their efforts must be articulated with the State and national and international organizations to facilitate an efficient performance of their role.

2.3. Pillars to build peace from the participation of private enterprise

If you could document what the private sector loses because of armed conflicts and what it would gain if there were peace, organizations that look to their own interests would prefer to invest time and money in peacebuilding, instead of bearing the uncertainty of markets, the devastation of resources that affects trade and the exchange of goods and services (Rettberg, 2010).

Despite the war, Colombia has had the ability to maintain a somewhat stable economy and its solid business structure, becoming the third largest economy in Latin America. In the country participate companies from around the world, several of them with a larger number of employees than all the men who make up the guerrillas (Ideas for Peace Foundation, 2015) and it is expected that there will be a cessation of the war, its GDP could be multiplied by two (Schippa, 2010).

The strength of the private sector allows to produce informal (49%) and formal employment (42.8%), that is, 91.8% of the employment is generated by the private company compared to 8.2% generated by the public sector (Guevara, 2003). From this perspective, the private company becomes the main partner of the State to build peace, generate opportunities for development especially in the local area where people have no greater possibilities of employment in state entities.

The private sector recognizes these conditions of the economy and knows that with a stable and safe country, business opportunities can multiply. Therefore, he understands that he must play a leading role in the post-conflict period, but he does not know the mechanisms to channel his effort and he fears that this responsibility will end up assuming only the private sector with the consequent economic and political costs (Velazco, 2006). Entrepreneurs lack clarity about institutional roles since there are many government institutions that participate in the process and send messages that are sometimes contradictory or divergent (ANDI, 2014).

Therefore, in this section, the main tools that the entrepreneur has to participate in a complex process are presented. The literature shows five mechanisms through which the private sector can actively participate in social construction:

As a financier of peace and post-conflict construction given its economic capacity, especially multinational companies (Kolk and Lenfant, 2013). The most effective and direct way to finance the construction of peace construction is through the payment of taxes, but also the businessmen have expressed their willingness to pay even some extraordinary contribution, since they consider that the economic effort, ultimately represents an investment needed to expand the business and have a greater chance of financial performance.

Through direct investment and strategic alliances, especially from national or multinational companies, which have great credibility, leadership, experience, and capacity to carry out actions of social importance (Abramov, 2010). Large companies generally invest in those states that have a higher level of justice (Appel and Loyle, 2012) and more reliable information systems (Garriga and Phillips, 2013), therefore the rules that regulate the post-conflict must give confidence, security, stability and clear “game rules” for investors.

Another form of investment is through strategic alliances between private enterprise, the State and NGOs, to achieve economic and social goals such as entrepreneurship projects, strengthening of productive chains, creation of employment and job training for people in vulnerable conditions. An example of these agreements is the partnership that the Swedish Government, the Colombian Government, and the private company have established through the ANDI, Ruta Motor and “Fondo Innovaciones para la Paz” foundations that promote productive projects, job creation, and value chains (Presidential Agency for International Cooperation, 2015).

Through Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) as ethical and moral compensation to society for allowing its actions (Jiménez, 2006), generally aimed at social investment and philanthropic activities that help to strengthen communities (Ospina, 2008). This mechanism is used mainly by large companies, but SMEs begin to understand its benefits and adopt it with greater confidence.

Within the Corporate Social Responsibility there are other specific guides that help the employer to build social actions and peacebuilding: a) the Global Compact of the United Nations Organization, b) the ISO 26000 guide, c) the guidelines of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) for multinational companies, d) the global reporting initiative, e) the voluntary principles of security and human rights and f) the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (Vargas, 2014).

In this regard, the National Association of Industrialists (ANDI), which is the most representative economic guild of the Colombian productive platform, in 2005, adhered to the Global Pact Network in which the signatory companies have a high commitment to respect of Human Rights, the environment, labor standards and the fight against corruption (Jiménez, 2014). This initiative makes the contribution of the company more significant, because the companies that make up this pact, are more likely to carry out concrete actions of peacebuilding, than those that only advance CSR programs by themselves.

On the other hand, if one considers the approaches of Swearingen (2010) and Robinson (2013) and accepts that the basis of the conflict lies in the inequalities and social injustices generated by private enterprise, since wealth is in the hands of a few and to the detriment of the majority, it is clear that actions should be oriented to transform the way these institutions operate, that is, to find a way to break that vicious circle represented in the actions of some organizations and in the absence of entities. of control that prevents the abuse of power (ANDI, 2014).

Through governance that allows small groups of populations or minorities to expand their participation from their own actors, realities, and problems (Roberts, 2011), and by seeking local strategies that resolve the roots of the conflict and take advantage of the capacities to achieve a sustainable peace (Matanock, 2016) built in situ (Figure 1).

Work becomes relevant when solutions of a global or international order cannot be applied in the same way everywhere due mainly to the gap between expectations and global norms compared to the capacity and knowledge of local institutions (Gizelis, 2016). Likewise, not all civil society organizations can play an active role in peacebuilding within these regulations (van Leeuwen, Verkoren, and Boedeltje, 2012). Local societies must resolve the frictions resulting from the inequalities that produce power relations between the local, the national, and the global (Björkdahl and Gusic, 2015).

Of course, these mechanisms are not new and companies, especially large ones, have gradually implemented them, although the ideal is for the entire productive sector to know them and adopt them with confidence and commit themselves to build a more equitable country. Oriented to the elimination of inequality and lack of opportunities, as the main causes of conflict.

3. Methodology

This is a study framed in the empirical-analytical paradigm with a quantitative approach, explanatory level, and non-experimental design. The population was formed by companies of all the country pertaining to the sectors of the commercial economy, services, manufacturing and financial. A simple intentional random sampling was carried out, in which 200 companies were selected to whom the questionnaire was applied to collect the information. This questionnaire was validated by expert judgment and a pilot test applied to 15 companies in the city of Cúcuta (Colombia). The questionnaire was structured by questions related to the perception of businesspeople regarding post-conflict, their knowledge about the forms of participation in peacebuilding, and the good practices carried out in this field. The questionnaire was solved in 2017 by managers or executives of the selected companies, located in the main cities of the country. Of the total number of participants, 70% corresponded to micro and small companies, 22% to medium-sized companies, and 8% to large companies. The information collected was processed through the statistical package SPSS version 2.1, one of the most used in the development of quantitative studies.

4. Results and Discussion

In this section we analyze the results about the perceptions of the entrepreneurs about the convenience of the end of the conflict and the construction of peace, how much they know about the topic and the availability to contribute in an effective way in the post-conflict, what degree of Knowledge exists about the process, and the actions necessary to make your efforts and contributions meaningful. The findings are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1 Results of the questionnaire applied to the companies participating in the study

| N° | Item | Yes | No | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N° | % | N° | % | ||

| 1 | Entrepreneurs’ perception of the appropriateness of the end of the conflict under the terms of the Peace Agreement | 186 | 93 | 14 | 7 |

| 2 | Entrepreneurs’ perception of the improvement of opportunities and conditions of the company based on the Peace Agreement or the post-conflict scenario | 180 | 90 | 20 | 10 |

| 3 | Knowledge and application of tools in the construction of peace - Corporate Social Responsibility | 150 | 75 | 50 | 25 |

| 4 | Knowledge and application of tools in peacebuilding - Protection of Workers’ Rights | 130 | 65 | 70 | 35 |

| 5 | Knowledge and application of tools in the construction of peace - Protection of Human Rights | 24 | 12 | 176 | 88 |

| 6 | Knowledge and application of tools in the construction of peace - Principles of the United Nations Protect, Respect, Remedy | 40 | 20 | 160 | 80 |

| 7 | Knowledge and application of tools in peacebuilding - Global Initiative | 20 | 10 | 180 | 90 |

| 8 | Knowledge and application of tools in peacebuilding - ISO Guide 26000 | 20 | 10 | 180 | 90 |

| 9 | Knowledge and application of tools in peacebuilding - OECD Guidelines | 30 | 15 | 170 | 85 |

| 10 | Knowledge and application of tools in the construction of peace - Global Compact | 120 | 60 | 80 | 40 |

| 11 | Disposition of companies in applying tools in the construction of peace - Corporate Social Responsibility | 146 | 73 | 54 | 27 |

| 12 | Arrangement of companies to apply tools in peacebuilding - Principles of the United Nations Protect, Respect, Remedy | 166 | 83 | 34 | 17 |

| 13 | Arrangement of companies to apply tools in peacebuilding - Global Initiative | 144 | 72 | 56 | 28 |

| 14 | Arrangement of companies to apply peacebuilding tools - ISO Guide 26000 | 148 | 74 | 52 | 26 |

| 15 | Disposition of companies in applying tools in peacebuilding - OECD Guidelines | 158 | 79 | 42 | 21 |

| 16 | Disposition of companies in applying tools in peacebuilding - Global Compact | 156 | 78 | 44 | 22 |

| 17 | Disposition of companies to support demobilized people in productive projects | 170 | 85 | 30 | 15 |

| 18 | Disposition of companies to provide employment for demobilized persons | 160 | 80 | 40 | 20 |

| 19 | Disposition of companies to establish alliances with other companies | 156 | 78 | 44 | 22 |

| 20 | The Willingness of companies to sponsor other companies | 74 | 37 | 126 | 63 |

Source: Author’s own elaboration.

4.1. On the convenience of the Peace Agreement, the end of the conflict and the post-conflict

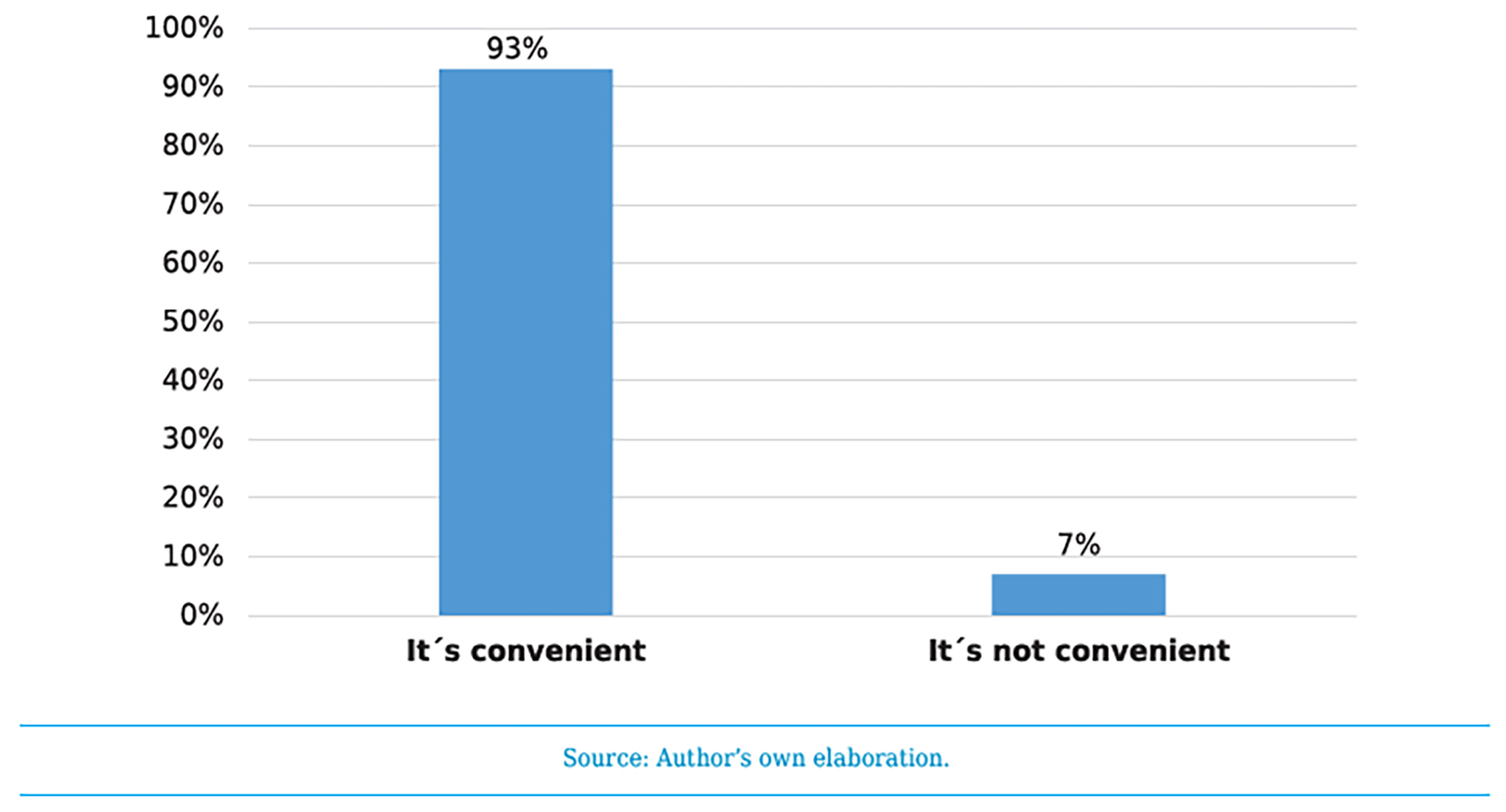

Most entrepreneurs are convinced that the end of the conflict will bring benefits and consider that the activity of the company would be developed with greater tranquility and security, and therefore 93% of the participants consider it convenient to end the conflict in the terms of the Peace Agreement as shown in Graph 1.

Graph 1 Businessmen perception on the convenience of the end of the armed conflict in the terms of the Peace Agreement

According to the businessmen, there will be greater facility to import and export products and raw materials, therefore, the company will be more competitive and will find other domestic and foreign markets; You can reach previously inaccessible areas where there are customers waiting for your products or services; It makes contact with strategic allies of the international order easier, as a consequence of legal and economic security in the country. All these conditions will facilitate the actions of the companies to generate employment, improve the purchasing power of Colombians, and increase consumption, which in turn will boost the economy and social development.

Entrepreneurs believe that if peace is consolidated, roads will be safer for the transport of passengers, merchandise, raw materials, and products, making companies more competitive. Tourism companies would improve their performance by opening the possibility of visiting other places of significant religious, historical, ecological, and cultural value, which could not be attended as a result of the war.

Other benefits that the end of the conflict will bring, according to the businessmen, will be the improvement in education, since it will be possible to build and improve the conditions of the colleges and universities, there will be a greater amount of qualified labor that will promote the economic and social development. The mining companies believe that it will be a great opportunity to exploit natural resources in a responsible and sustainable way, in areas previously inaccessible due to the armed conflict, and compete successfully in international markets. Most entrepreneurs believe that there will be better opportunities and opportunities to improve portfolios, diversify their businesses, generate employment, and expand the tax base so that the country has greater income.

Despite the enthusiasm of businessmen, there are those who believe that there will be negative consequences such as the increase in taxes to finance the post-conflict, greater competition in the market due to the entry of large multinationals, as well as the fear that other violent actors will emerge. occupy the spaces left by the guerrilla. These new challenges, according to the businessmen, are much more manageable than those that are faced with the heat of war.

Entrepreneurs make a general reference to the opportunities and advantages of the Peace Agreement and the post-conflict period, but that view is marked by the nature of the homo oeconomicus, that man whose interest is marked by profit and profit, and that according to it, it guides their perception, decisions, and courses of action (Foucault, 2007). In effect, the employer through his answers emphasizes the possibilities of investment and growth but does not emphasize the global changes implied by the cessation of the armed conflict beyond the economic. In that sense, they do not know that the cessation of the armed conflict, despite being a great step forward, does not imply securing the required peace conditions, in other words, that it is necessary to go to the bottom of the causes, eliminate them, and modify the conditions of poverty, inequality, and inequality, as part of the reconstruction of the social fabric as observed in the maximalist vision (Rettberg, 2003).

4.2. On the knowledge and application of tools by entrepreneurs in the construction of peace and/or contribution in the post-conflict

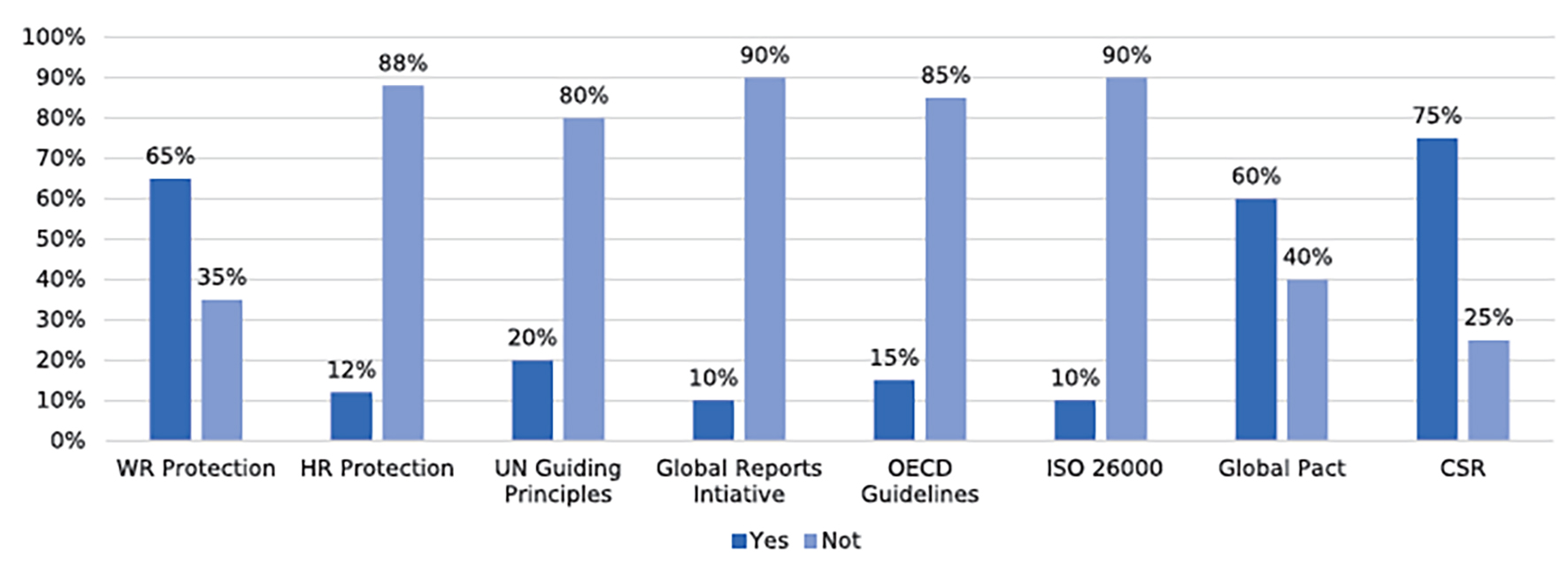

Graph 2 shows in a general way the application of tools for the construction of peace by participating companies, highlighting the Corporate Social Responsibility, the protection of workers’ rights and the Global Compact.

When inquiring about the knowledge and application that companies have about some tools that could contribute to the construction of peace, it is found that 75% know and apply Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), especially large companies. Most companies claim to have adequate and systemic practices to protect workers’ rights (WR Protection), although the guiding principles of the UN that oblige companies to protect rights related to work, safety, the environment, are unknown. environment, housing, and the rights of indigenous peoples. Thus, employers have created their own guides, regulations, and processes, so that in their actions, the employees are guaranteed decent work, right of association and safety for workers and their families.

Similarly, only 12% of the observed companies state that they promote the protection of Human Rights (HR Protection), and do not know in depth mechanisms such as the ISO 26000 guide, which offers recommendations on the behavior of organizations in relation to the prevention of direct violence and the protection of human rights.

In the same sense, only 20% say they know and apply the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, and the Voluntary Principles of Security and Human Rights, which make explicit the obligation to protect, respect and remedy within the framework of human rights. The same thing happens with the guidelines of the OECD and the Global Compact that although they are already known tools, they cannot be implemented in most of the participating companies.

It should be noted that there are many companies that are already betting on peacebuilding through Corporate Social Responsibility actions such as Bancolombia, which works to protect forests, water, and biodiversity; Ecopetrol does it looking for ways for water and oil to coexist without contaminating aquifers, rivers, and streams; the Argos Group has focused on conserving the environment and protecting biodiversity; the Sura Group promotes through education the healthy coexistence and the prevention of violence against children; Manuelita promotes education in classrooms and homes for the most vulnerable children; Promigás promotes inclusion, equity, social mobility, and freedom (Semana Magazine, 2017).

Other companies that also carry out actions of responsibility are Terpel and Coca-Cola-Femsa, which provide job opportunities for ex-combatants and facilitate their incorporation into civilian life. The Corona company makes violent zones become convivial scenarios, the Éxito Group develops programs to eradicate chronic malnutrition in children, Postobón supports small farmers, The Nutresa Group, through the Germinar program, helps many rural families to forge a better future, and the Chamber of Commerce of Cúcuta works in the labor reconversion and the consolidation of local governance.

Some organizations have created different foundations with private capital, support and coordination of the public sector, making progress on issues related to the promotion of fundamental rights and social development, improving the income of displaced and vulnerable populations lacking resources, support in education and housing , business development, culture recreation and good treatment, humanitarian attention and citizen management, local integral development, development of sustainable projects that generate employment and well-being for vulnerable populations, prevention against the risks of forced recruitment, drug trafficking and gangs, credit service to small producers, and human, technical and business training (Arteaga, 2012).

However, it should be noted that Corporate Social Responsibility is a scenario of voluntary action, and to that extent, the programs and strategies advanced by the company are strongly influenced by the interest of the homo oeconomicus, and in part, this explains the global ignorance of the tools for the construction of peace and its scarce application in practice as well described by Prandi (2010)b or Montañés and Ramos (2012). But this ignorance is not accidental or circumstantial, because when the entrepreneur is mobilized by private interest, it is precisely their low level of interest that leads to their ignorance and inapplicability. In this way, it is not enough with the invitation of the State to the companies for the application of programs or strategies for the support in the construction of peace and transit through the post-conflict, since it is necessary to motivate their participation based on benefits and opportunities, and especially, the construction of a culture on the need for active participation in the process (Millar, 2016).

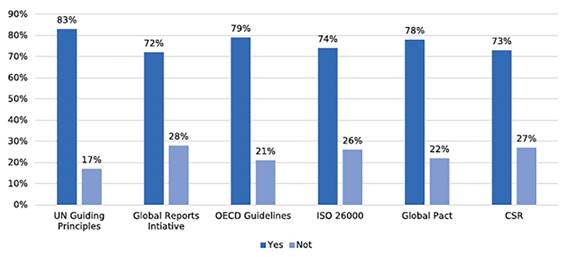

4.3. On the availability of companies in the application of tools in the post-conflict

The ideal is for all large and small entrepreneurs to participate in this dynamic, so entrepreneurs were asked about the willingness to learn and implement the tools already mentioned. Most of the participants showed a favorable position in the adoption and application of the tools as shown in the results described in Graph 3. In this aspect the government and the universities have one of the greatest challenges, to spread the benefits and effectiveness of these instruments, that would have for the construction of peace if it was implemented in an adequate, systemic way and in the vast majority of Colombian companies.

As has been said, one of the tools available to private companies to be influential actors in post-conflict and peacebuilding is through strategic alliances with the government, NGOs or other private companies, national or foreign, with national or local coverage. When inquiring about this type of alliances, it is found that less than half of the companies have had some experience of helping or being helped by other companies to consolidate in the market. However, more than 75% of them are willing to establish strategic alliances, in addition to employing demobilized persons, promoting productive projects in areas where there was conflict before, and buying products generated by companies made up of demobilized combatants.

It would be significant for companies to consider their relevant role in the economy and in the generation of both formal and informal employment, which is higher than 91% of total jobs (Guevara, 2003). In case of improving the economic, commercial and productive landscape, the first priority of the companies should be the generation of more decent jobs, which leads to the need to change that perspective of demanding cheap labor from the market and modify it by an innovative and competent human capital that generates added value for companies. Of course, this involves multiple instruments related to Human Rights and workers’ rights, which reduces the willingness to participate voluntarily in strategic alliances and the development of social and economic programs.

4.4. On the availability of the companies in the support to demobilized and the construction of strategic alliances

According to the information gathered, there is a great opportunity to create strategic alliances and productive projects that impact society, especially in vulnerable areas affected by violence. These alliances provide for micro businesses and family businesses to be able to consolidate and contribute to the generation of wealth and social development. It is worth noting that most of the companies that exist in Colombia are located within this category -micro and small companies-, and therefore, linking them to the post-conflict process and the construction of peace is fundamental, of course, from a perspective that not only involves them as sources of employment and subjects that contribute to the processes but also as objectives of the same benefits provided by large companies (United Nations, 2012).

Finally, it is emphasized that businessmen are willing to make additional economic contributions for the purpose of peacebuilding. Nearly 50% answered that they are willing to make voluntary contributions, highlighting the commitment and decision of the sector to consolidate peace. It should be noted that while this investigation was being conducted, the National Government promoted a tax reform in which some taxes are increased and other products that were previously exempt from taxes are included.

5. Conclusions

The Colombian business sector expresses a general positive attitude towards the post-conflict and the possible benefits of this process for the economy and the market, although they express concerns about the scope of the role they will have to fulfill with respect to it, for example, increased taxes or higher economic burdens, or the increase of competition in case of greater foreign investment. Even so, a significant percentage of entrepreneurs are willing to implement mechanisms and instruments to contribute to the post-conflict and peace-building scenario, such as Corporate Social Responsibility and the United Nations Principles for Protecting, Respecting and Remedying, and support other initiatives in favor of demobilized persons with their participation. It is worth noting that a significant number of companies do not currently know or apply tools for the protection of Human Rights, the United Nations Guiding Principles for Protecting, Respecting and Remedying, the Global Initiative, the ISO 26000 Guide and the Guidelines for the OECD, being necessary that the Colombian State manages to link from its strategies and public policies to the companies in the post-conflict and the construction of peace.