1. Introduction

The 2016 tax reform in Colombia was initially presented as a leap forward under the assumption that it reckoned several shortcomings in the Colombian tax system. In this regard, it was suggested that it was structural, comprehensive and progressive, although after more than a year of enactment it is evident that such a thing is false, and that in fact the next government, regardless of its ideological or political current, will have to enact another reform in the short term. It cannot be said that a tax reform is structural if it does not address the problems associated with public spending, nor integral when it neglects the problem of weak subnational taxation, and clearly it is not progressive if the greater collection is pursued through VAT and taxing the working class to a greater extent.

In fact, the premises underlying the final report by the Comisión de Expertos para la Equidad y la Competitividad Tributaria (2015) (Commission of Experts for Equity and Tax Competitiveness) were well known, thanks to several previous studies that effectively showed that the Colombian tax system was inefficient, inequitable and complex (Steiner and Cañas, 2013).

And while reasonable measures were introduced, such as taxing capital income and dividends, at least partially and regardless of whether under other standards they were considered not to constitute income or occasional gain, there were also changes that counteracted them, as did the non-incorporation of minimum levels of taxation that would take the total income as a reference, regardless of its source.

Thus, the package of reforms and counter-reforms prevented the Colombian tax system from moving in the right direction, so that the State does not yet have a stable source of income that will help it effectively fight poverty and achieve a more inclusive society. Currently, most analysts (e.g.,Fitch, 2018; Fedesarrollo, 2017) agree that financing the current level of public spending and compensating for the fall in some sources of income (i.e., the disappearance of Wealth Tax and the excess tax on Corporate Income Tax) requires undertaking a new reform cannot concentrate on VAT this time, as the precedent of 2016 makes promoting this type of measure very costly politically.

This restriction could suggest that the tax burden of the working class should continue to be increased through Personal Income Tax, as has been done in the past. However, this work is concerned with showing that instead of seeking to extract more resources from the same agents, who are already fully identified by the DIAN (National Directorate of Taxes and Customs, per its acronym in Spanish), the case of employees in the formal sector, the fiscal pact should be extended to new agents, which means strengthening the fight against evasion and omission, for example. In addition, and despite the belief that greater collection and progressivity are incompatible purposes, this work uses international comparison and empirical evidence to show the opposite. Therefore, direct taxes should be used more intensively, but maintaining progressivity as the guiding principle, which would also promote voluntary compliance in taxpayers’ obligations.

In addition to this introduction, the text includes four other parts. The first one reviews the problems in the Colombian tax system identified before Act 1739 of 2014 created the Comisión de Expertos para la Equidad y la Competitividad Tributaria (Commission of Experts for Equity and Tax Competitiveness), and shows that low collection, inequity and complexity, for instance, are features present in national taxation since long ago. The second section indicates that the problems mentioned above have legitimized some reforms in the matter, but have not been effectively resolved, wherefore it is useful to analyze the advances and setbacks (counter-reforms) introduced by Act 1819 of 2016 in this area. It is thereafter proved that the dilemma between collection and progressivity is false, through a data panel that includes observations for 138 countries during the period 1976-2015. The fourth part presents conclusions and recommendations, which can serve as benchmarks for a forthcoming reform attempt.

2. Background to the 2016 tax reform

The significant drop in international oil prices of 2014 led the Colombian government to consider alternatives to compensate, at least partially, for the respective loss of capital resources (given the lower profits reported by companies such as Ecopetrol). In particular, Article 44 of Act 1739 of 2014 provides that a Committee of Experts would be created to study the Colombian tax system, especially the scheme applicable to non-profit entities and the existing tax benefits. The objective of this, according to the Act, was to achieve greater equity and tax efficiency.

If the tax reform of 2014 (Act 1739 of 2014) is considered, it had a fiscal objective, as it concentrated on introducing various measures aimed exclusively at generating greater tax revenues. Among these changes is the creation of the Wealth Tax, which in reality meant postponing the removal of the Net Worth Tax1; together with the incorporation of a complementary tax for taxpaying standardization and the setting of an income tax surcharge for equity (CREE per its acronym in Spanish) between 2015 and 2018 (Art. 22 of Act 1739 of 2014). Thus, the establishment of the Committee of Experts could be seen as another initiative to legitimize future tax increases.

Indeed, the tax reform of 2016 continued with the tendency to increase revenue, even more so when the Wealth Tax and its standardization supplement, the surcharge on CREE and the Tax on Financial Movements (GMF per its acronym in Spanish) had a certain validity, implying that the tax burden should start to fall from 2018 if something was not done about it. This, coupled with the fall in international oil prices, put strong pressure on public finances (Comisión de Expertos para la Equidad y la Competitividad Tributaria, 2015) and called into question compliance with the tax rule established by Act 1473 of 2011.

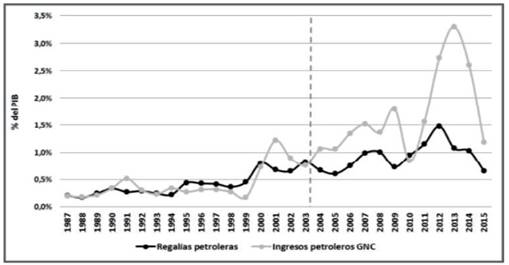

As shown in Graph 1, since 2003 the central government’s revenue from oil, represented by the income tax paid by this sector and the dividends paid by Ecopetrol grew by more than 400% (from 0.8% of GDP in 2003 to 3.3% of GDP in 2013). Similarly, local authorities benefited from the boom in the mining and energy sector through royalties, which amounted to 1.5% of GDP in 2012. Nevertheless, with the sharp drop in international oil prices in 2014, these revenues also fell to about 1.2% of GDP and 0.6% of GDP respectively, contributing to the growth of the fiscal deficit.

In other words, as another example of the Colombian tradition regarding tax reforms, the most recent was also part of the government-in-power-at-the-time’s adjustment program to a changing economic context. Although this is not particular to the Colombian case, it does show that when tax changes are discussed in times of crisis, the usual is that objectives such as raising revenue take precedence over others (e.g., equity).

In this scenario, the Comisión de Expertos para la Equidad y la Competitividad Tributaria (2015) presented its diagnosis on the Colombian tax system. It gave an account of how inefficient it was and its underlying inequity, with the aim of legitimizing its proposals to solve these problems. However, it should be noted that this diagnosis was not something entirely new, since several studies had already proposed the same, without the government’s attention to the respective recommendations (Steiner and Cañas, 2013).

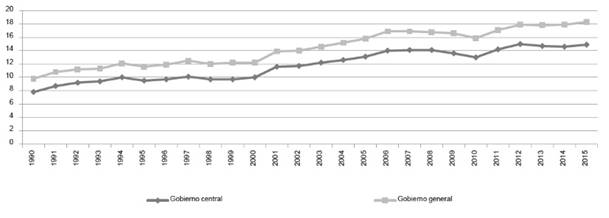

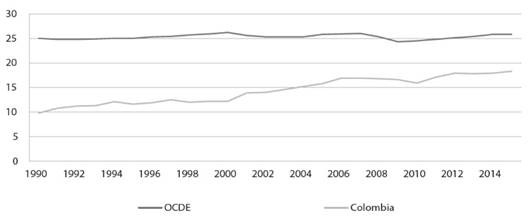

For instance, although it can be seen that the tax pressure associated with the central (general) government grew on average by 4.4% (4.3%) annually between 1990 and 2015, going from 7.8% (9.8%) to 14.9% (18.3%) of the GDP respectively (Graph 2), this does not imply that this level is consistent with what could be expected according to the degree of economic development of the country (ECLAC, 2016). In addition, and due to the existence of numerous special tax benefits (e.g., exempt income specific according to the economic sector), it is reasonable that there are also numerous economic distortions related to the tax system (Comisión de Expertos para la Equidad y la Competitividad Tributaria, 2015).

It is important to take into account the above because tax efficiency refers not only to collection, but also to the economic costs arising therefrom (the so-called deadweight loss in specialized literature). In this regard, the Constitutional Court has stated, for example, in Sentence C-776 of 2003, that a “tax is efficient in so far as it generates few economic distortions. So is, although from another point of view, the tax that allows obtaining as much resources as possible at the lowest possible cost.”

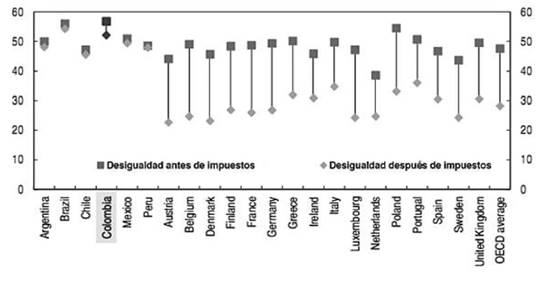

On the other hand, a comparison between the Gini coefficient before and after taxes shows, at least with figures from 2012, that the Colombian tax system did very little to redistribute income. Graph 3 shows that unlike developed countries (mostly OECD members), in Latin America, and particularly in Colombia, the reduction of Gini is limited after the government charges taxes, which is explained by factors such as the various tax benefits that disfigure tax bases, evasion and the low share of taxes aimed at redistribution in total revenue (e.g.,Castañeda Rodríguez, and Díaz-Bautista, 2017).

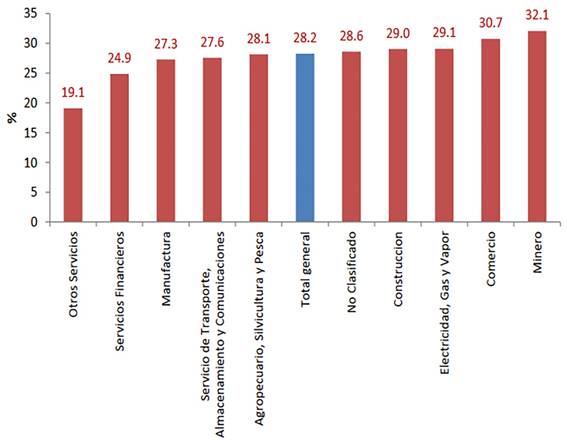

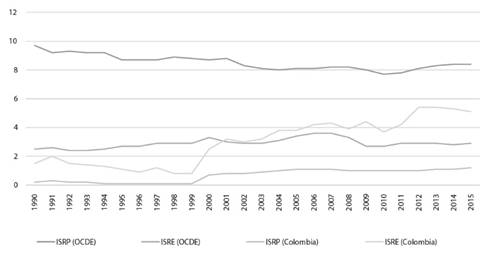

Related to the above, there are several studies that in the last decade have been concerned with analyzing the degree of tax equity of VAT and Income Tax (ISR per its acronym in Spanish), both personal (ISRP per its acronym in Spanish) and corporate (ISRE per its acronym in Spanish). For instance, Steiner and Cañas (2013), using data from 2012, measure the redistribution effect of these taxes and find that only ISRP has a progressive structure, so that the Effective Tax Rate (TET per its acronym in Spanish) grows as the income level increases. In the case of VAT, this rate goes from 4.43% on average for households in the first decile to 2.80% for households in the tenth decile; meanwhile, for the ISRE there is a high dispersion of TETs between sectors (Graph 4).

In this regard, it was evident that the numerous differential tax benefits, which disfigure the tax bases, together with the high evasion and the low participation that sources such as the ISRP have in the collection, had an impact on these results. Of course, these factors tend to reinforce each other.

For example, one way of measuring the importance of differential benefits in the tax system is through tax expenditure, a term that refers to the revenue that the State ceases to receive on the occasion of the former. However, regardless of whether a legal framework or reference model is used - without differential benefits- to calculate the loss of revenue, it can be between 20% and 30% of the current tax burden (Table 1), a range that also underestimates the real magnitude of the problem. Indeed, these calculations only consider the tax expenditure associated with VAT and ISR, since estimates are not yet available for other national or territorial taxes (Banco Mundial, 2012).

Table 1 Tax expenditure (% of GDP) in Colombia according to DIAN and World Bank estimates

| Tax cost | DIAN | World Bank |

|---|---|---|

| Income Tax | 1.56 | 2.4 |

| Corporate | 1.23 | 1.4 |

| Personal | 0.33 | 1.0 |

| VAT | 1.6 | 2.1 |

| Total VAT and ISR | 3.16 | 4.5 |

Source: World Bank (2012).

On the other hand, although the evasion of VAT and ISR in Colombia is comparatively below the Latin American average, it still represents a significant loss of revenue and a source of tax inequity. According to ECLAC (2017), VAT evasion in Colombia for 2015 was 20.1% of the revenue potential, while for ISR the figure amounted to 34.4% (the latter based on 2012 data).

Likewise, and according to Gómez-Sabaíni, Jiménez, and Rossignolo (2011), evasion affects the distributive effect sought by a tax system, especially with regards to the ISRP. Individuals with equal capacity to pay will not necessarily bear the same tax burden (horizontal inequity) and those with greater capacity to contribute also have more alternatives (e.g., professional conculrancies) to arbitrarily reduce their tax burden (vertical inequity).

All of the above, in conjunction, helps to analyze the differences that still exist in tax matters between developed countries (e.g., most OECD members) and developing countries, particularly Colombia. Although the revenue gap has been closed, so that today it stands at around 7.5% of the GDP (Graph 5), the remarkable thing is that much of it is explained by the ISR, and especially by the low productivity of the ISRP in Colombia.

While the difference between ISR revenue between OECD (average) members and Colombia has narrowed from 10.5% of the GDP in 1990 to about 5% of the GDP in 2015, this has not been the result of deliberate policy. In part, this is the effect of the decline in the ISRP in developed countries, which according to Castañeda-Rodríguez (2016) is associated with the advancement of globalization, as well as the increase in ISRE in Colombia on the occasion of the increase in international prices of raw materials during the first decade of the 2000s (Jiménez, Gómez-Sabaini, and Podesta, 2010).

However, Graph 6 indicates that Colombia underuses the ISRP, obtaining only 15% of what is collected on average by OECD member countries. On the other hand, and with regards to ISRE, in Colombia there is almost double the amount compared to the OECD. This means that the ISR structure in the country favors collection based on corporate income, which is reasonable if we consider the institutional weaknesses to engage greater tax controls on natural persons, which, in addition to being numerous, implies a less favorable cost-benefit relationship for the DIAN.

In connection to this point, the Comisión de Expertos para la Equidad y la Competitividad Tributaria (2015) linked the low ISRP collection with the existence of high sections exempted in comparison with international standards. In addition thereto, the existence of numerous tax benefits was argued as a factor limiting the redistribution capacity of this tax, which added onto the application of different categories (i.e. employees, self-employed workers and others) and purging models, made tax compliance difficult, as well as the administration and control of DIAN.

Therefore, an apparent simplification for the ISRP was proposed through the elimination of the National Minimum Alternative Tax (IMAN per its acronym in Spanish) and the Simple Alternative Minimum Tax (IMAS per its acronym in Spanish), in addition to the same for the ISRE. This was also coupled with the limitation of some tax benefits, so that certain sources of income such as pensions and dividends were taxed, and by the reduction of the minimum amounts for filing2.

Nonetheless, despite the endemic problems of the Colombian tax system, recent tax reforms have focused on increasing the tax burden on taxpayers who can easily be identified by DIAN, to wit, the employees in the formal sector. Furthermore, and by virtue of the foregoing, the tax burden for legal entities that meet with their tax obligations may become unsustainable, according to the TET per economic sector, regardless of whether the ratio between direct taxes, both in the national and local order, and the profit declared before taxes, or replace the latter with the gross operating surplus of the National Accounts. For example, the Comisión de Expertos para la Equidad y la Competitividad Tributaria (2015) showed that this indicator could range from 46% to 104% or between 8.8% and 43.5%, depending on the methodology used.

This explains why the Comisión de Expertos para la Equidad y la Competitividad Tributaria (2015) also proposed the elimination of the CREE along with its excess tax, and proposed the creation of a new tax on corporate profits that would have a statutory fee between 30% and 35% applied on accounting profits. This meant eliminating much of the tax benefits, which not only give rise to an unequal tax burden between sectors (Graph 4), but also favor the concentration of revenue collection on a few taxpayers in relation to the universe of potential taxable entities. Despite the good intentions of this reform, the upcoming section will show that each progress was accompanied by a setback or limitation that does not allow it to be described as structural, integral or progressive.

3. Amendments and counter-forms to Act 1819 of 2016

Some of the well-known issues of the national tax system in Colombia, which at the time were considered by the Comisión de Expertos para la Equidad y la Competitividad Tributaria (2015) to justify its proposals, have been synthesized. Now, it is pertinent to indicate which changes were approved, evaluate their relevance and identify those reforms that mean a setback. Therefore, the following are some proposals that were taken into account during the tax reform debate in 2016 and that were approved at the end of the legislative process, without the intention of constructing a specific list.

However, it is important to note that some of the changes mentioned in Table 2 may have only a marginal effect on the objectives initially set by the reform, since they coincide with a series of errors or other modifications limiting their scope, and that for expository purposes they are referred to herein as counter-forms. Firstly, the aim was to rationalize various tax benefits, both for ISRP and ISRE, but aspects such as simplicity, fairness and non-confiscatoriness were unknown. For example, in the case of the ISRP, some restrictions are difficult to apply because the wording of the rule attendant thereon is unclear or the right to impute appropriate deductions is unknown.

Table 2 Some of the proposals approved by the Comisión de Espertos

| ISRE | ISRP | VAT | Tax avoidance and evasion Control |

|---|---|---|---|

| CREE removal. | Elimination of IMAN and IMAS. | Increase in the general rate (from 16% to 19%). | Creation of a procedure to access the Special Tax Regime. |

| Recognition of revenue, costs, expenses, assets and liabilities in accordance with IFRS. | Separation of income according to source for the purpose of calculating the tax payable. | Change in the type of purchases of fixed assets resulting in discountable VAT. | Classification of evasion as a criminal offence. |

| Limitation of some tax benefits. | |||

| Creation of the Regime for Small Taxpayers. | |||

| Modest increase in taxation on dividends and equity. |

Source: Author’s own elaboration.

In this regard, Table 3 shows the percentages set as a restriction for exempted income and chargeable deductions in the ISRP statement, but the respective limits applicable to non-labor and capital income appear with a question mark, since that value would be applied to a balance to which costs and expenses incurred would have already been charged (i.e. deductions), thus creating a circularity problem. Now, if to avoid this such percentage is supposed to be applied on net income (i.e., gross income minus Non-taxable income), this alternative would make the tax burden on these taxpayer group quite burdensome (confiscatoriness)3. the above is also true for dividends and shares, which in the beginning cannot be affected by deductions, suggesting that those who receive such income are not entitled to include expenditure such as social security contributions.

Table 3 Restrictions on exempted income and deductions according to taxpayer type

| Income | Limit exempted income and deductions (%) | Exempt income limit and deductions (UVT) |

|---|---|---|

| Employment income | 40% (of net income) | 5.040 |

| Capital income | 10% (?) | 1.000 |

| Non-employment income | 10% (?) | 1.000 |

| Income from dividends and shares | It is understood that there are no exempted income or deductions that apply to this schedular income. This is not consistent with Article 135 of Act 1753 of 2015, the doctrines of the UGPP and Sentence C-711 of 2001). |

Source: Author’s own elaboration based on Art. 1 of Act 1819 of 2016.

With regards to the ISRE, while it was necessary to control the many tax benefits that are a source of inefficiency and inequity, it is not clear why in several cases the respective differential benefits was eliminated only for natural persons. For example, the progressivity benefit in the rate of the ISR created by Act 1429 of 2010 was repealed through Article 376 of Act 1819 of 2016, although Article 100 thereof indicates that legal entities will maintain it for a maximum period of five years, with a minimum fee of 9%. This results in inequitable benefits between taxpayers, depending on whether it is a natural or legal entity that was formalized during the tax incentive created in 2010.

It must be recognized that eliminating various tax benefits from their origin, by repealing the respective rules that gave rise to them, is politically unlikely, since such reform needs to be negotiated with the legislature and the various stakeholders. However, if the government opted for a strategy such as creating overall limits to reduce the respective tax spending, more attention should have been paid to the inaccuracies and differentiations found in the approved reform, since this, in addition to promoting inequality, contributes to the complexity of the tax system. For instance, nowadays it is usual for any tax consultant to indicate that the schedular income system, for purposes of the ISRP, is more complex than that in force until 2016, onto which is added the lack of regulations in this area.

Someone could rightly argue that a progressive system will usually require some dose of complexity, so that the schedular system created by the 2016 tax reform could be the means to achieve that end. However, it is relatively easy to find counterexamples that indicate that this is not true, and that even the ISRP may end up being regressive, to the point that the higher revenue will be borne by those taxpayers who concentrate their income on wage sources.

For example, incorporating five schedules into the purging of the ISRP will not always mean higher collection and progressivity, since this system allows dividing the same income into several sources so that a taxpayer is less likely to reach the ranks with higher marginal rates. In this regard, two natural entities can be considered, one with an income of $100 million associated with a single schedule (labor income) and the other that obtains $120 million from two sources ($40 million for wages and $80 million for retail trade activities).

Table 4 shows the statements that would be necessary if the data referred to the year 2017 under the following assumptions: (1) both individuals make only the obligatory contributions to the Social Security (SS), i.e. there is no tax planning, and the costs attributable to trade activity amount to 20% of non-labor income to partially offset the benefit enjoyed by labor income according to Article 206-10 of the Tax Statute (ET per its acronym in Spanish).

Table 4 ISRP Statement under the shcedular model for two persons

| Person A | Person B | |

|---|---|---|

| Wages | 100.000.000 | 40.000.000 |

| INCRNGO | 8.308.000 | 3.323.000 |

| Deductions | 0 | 0 |

| Net income | 91.692.000 | 36.677.000 |

| Exempt income (art. 216-10 ET) | 22.923.000 | 9.169.250 |

| Taxable net income | 68.769.000 | 27.507.750 |

| Labor income tax (art. 241 of the ET) | 7.786.000 | 0 |

| Trade revenue | 0 | 80.000.000 |

| INCRNGO | 0 | 7.296.000 |

| Deductions | 0 | 16.000.000 |

| Net income | 0 | 56.704.000 |

| Exempted income | 0 | 0 |

| Taxable net income | 0 | 56.704.000 |

| Non-labor income tax (art. 241 of the ET) | 0 | 6.243.000 |

| Total taxes | 7.786.000 | 6.243.000 |

| The INCRNGO (Non-taxable income or Occasional Profit) includes the contributions (adding 1% of pension solidarity thereunto) to the Social Security (SS) of employees, that is, 9% of their labor income without the service premium. Regarding the contributions to the SS associated with the realization of trade activities (total rate of 28.5%), the income is taken ($80 million) and the imputable costs and deductions are subtracted ($16 million); 40% of this figure constitutes the basis (Act1753 of 2015). | ||

Source: Author’s Own elaboration.

Table 4 indicates that the possibility of subdividing an income into different sources allows the individual in the example with greater capacity to pay, to pay fewer taxes compared to those who earn only labor income. That is, the ISRP becomes regressive in this particular case. This is one of the reasons why it is said that the middle-income working class in Colombia tends to bear much of the increase in revenue after the approval of tax reforms such as the one in 2016 (Espitia, Ferrari, Hernández, González, Reyes, Villabona, and Zafra, 2017), as they can be monitored relatively easy because of their formal job and their tax obligation is collected as it is carried out, through monthly deductions made by employers.

Also, the tax burden for some companies remains high. Act 1819 of 2016 created a surcharge on the ISRE for the period 2017-2018 (transitional paragraph 2 of Article 100 of the aforementioned Act) and incorporated a differential rate of 9%. Therefore, the statutory rate of this tax could be around 40% in 2017 and 37% in 2018, so that those who meet their tax obligations and are not beneficiaries of multiple tax benefits will continue to pay high taxes.

Although tax benefits in certain sectors represent significant tax savings (Steiner and Cañas, 2013), this does not exclude the possibility that the tax burden remains excessive for someone. In other words, just as there are taxpayers who pay high taxes, there are also many who do not, either because they evade or because the law allows them to, so direct tax collection in the aggregate will remain low. An example thereof is that the fulfillment of the 2017 collection target depended for the most part on the increase in VAT, and that it is precisely this tax added to the National Consumption Tax that experienced the greatest dynamism in that year, growing 19.5% compared to 2016, while total revenue grew by 7.7% (based on DIAN statistics).

Along the lines of the tax simplification objective, recognition of assets, liabilities, equity, revenues, costs and expenses was allowed as prescribed by IFRS for accountants, despite some exceptions (see e.g. the current version of Article 28 of the Tax Statute). Nevertheless, a formal obligation to perform a tax reconciliation was also established, which, together with the periodic certification to be submitted on the non-use of adjustments related to the Opening Statement of Financial Standing for tax purposes, implies an increase in compliance costs. In short, tax simplification in this case remains only a good purpose.

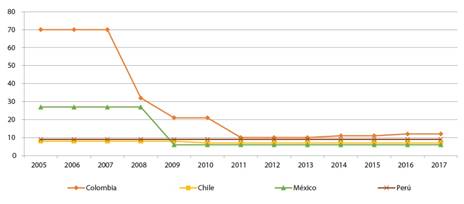

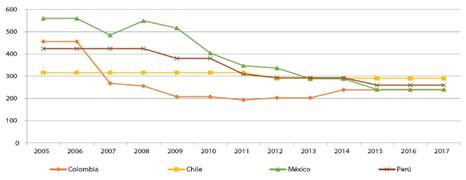

Through two indicators provided by the World Bank (Doing Business database), such as the number of taxes and contributions a medium-sized company must pay during the year or the number of hours it takes on average to meet its formal and substantial tax obligations, it is possible to gain an idea of how complex a tax system is. When comparing Colombia with its peers in the Pacific Alliance, there are currently no great differences, and there is even some convergence in the respective values (Graphs 7, 8). However, it is also true that progress in “tax simplification” is concentrated between 2006 and 2008, so that the latest tax reforms carried out in the country have not led to major changes in this area.

Graph 8 Average number of hours a medium-sized company spends to meet its tax obligations (Pacific Alliance)

Furthermore, while the custodial penalty was created for two particular offences, the omission of assets or inclusion of non-existent liabilities on the one hand, and the non-payment of withholdings or VAT, the effective application of this measure is unlikely. It was intended to discourage evasion, which is one of the reasons for low collection in Colombia, but the amounts and conditions for the criminal process to advance make this measure ineffective. In fact, Article 338 of Act 1819 of 2016 fixed an amount associated with the inaccurate information of 7,250 legal minimum monthly wages (just over $5.348 million for 2017) so that the respective penalty is deprivation of liberty. Moreover, articles 338 and 339 of that Act allow the prosecution to be terminated if the defendant decides to pay the due for his offense to the tax administration.

In short, the 2016 tax reform readjusts upward the tax burden on account of ISR for many of the taxpayers about whom DIAN already had information, especially wage earners, and additionally bets on a well-known strategy in Latin America when it comes to solving tax problems, i.e., increasing the general VAT rate. However, it does not establish specific measures to enable the tax administration, among other things, to detect omitted natural entities, who, by making a massive use of cash, evade their obligation to contribute to State financing, as set out in Article 95 of the Constitution.

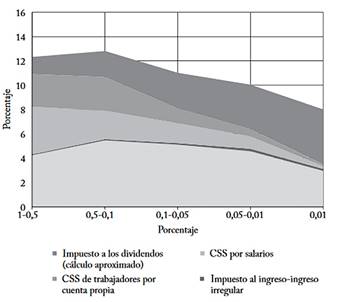

Thus, it is difficult to improve in aspects such as tax efficiency and at the same time increase the participation of the wealthiest population in the collection (i.e., progressivity), a fundamental fact if one considers the persistent income inequality in the country. Indeed, according to Alvaredo and Londoño (2014), by 2010 around the top 1% of the population distribution concentrated 20.4% of total income, a figure that has not changed much in recent years and that contrasts with the fall in TET, as income among different fractiles associated with this percentile increases. Graph 9 indicates that, based on tax data, the Colombian tax system turned out regressive if the behavior of the tax burden was taken into account within the richest 1% of the population.

Graph 9 Distribution of the tax burden by ISRP within the richest 1% of the Colombian population (2010)

In general terms, it has been argued up to now that the recent tax reform does not do much in terms of simplification nor does it favor the progressive nature of the system, despite the high inequality in income distribution that Colombia suffers. In addition to this, it is hoped that this year the sitting government again seek to increase the collection, since the tax effect of Act 1819 of 2016 will not last long. In this regard, the increase in VAT will not be sufficient to finance the reduction in the collection of the Wealth Tax and the ISRE, which makes it possible to anticipate a forthcoming reform (e.g.,Fedesarrollo, 2017).

4. The False Dilemma Between Revenue and Progressivity

The previous paragraphs have shown that Act 1819 of 2016 was another tax reform that is little structural, progressive or integral. Now, some light has been shed on what could be proposed for a forthcoming reform, which should be presented at the end of 2018 given the present juncture. On the one hand, increasing the level of collection means not only taking advantage of some historically underutilized sources, such as ISRP, but also reducing evasion levels.

In this vein, a reasonable option is to improve the redistribution potential of the ISR, for example, by keeping up the strategy of limiting the various tax benefits that still exist and have no economic justification (e.g. tax discounts for donations and exemptions for contributions to AFC accounts), since increasing VAT, on the other hand, is not feasible after the increase of its general rate to 19%. Although it is sometimes suggested that this discourages accumulation and investment, two aspects can be considered. Firstly, the low collection in Colombia is partly explained by the low productivity of the ISRP (Graph 6) and, in addition thereto, some studies have come into the light, which attest to inequity in this type of tax and favors a low tax morale that consequently induces a greater tax breach (Doerrenberg and Peichl, 2013).

In fact, the latest tax reforms in Colombia have been presented under the principle that investor confidence must be kept, and that in this sense it is not appropriate to increase marginal rates in the ISRP, nor to increase the ISRE rate, even less so when in an open context this could motivate an outflow of capital (e.g.Castañeda-Rodríguez, 2016). Thus, a recipe followed in general has been to tax to a greater extent those less elastic bases, the case of consumption and income from work. In other words, it is assumed that in order to obtain more revenue, an acceptable cost is the loss of progressivity, as if there were actually a trade-off between the two objectives.

However, here it becomes necessary to establish whether the apparent contradiction between progressivity and collection is true. For this purpose, econometrics can be used to study the behavior of tax collection levels and their relationship with several variables, already widely discussed in the literature on determinants of taxation, incorporating in addition some indicator of the level of tax progressivity.

In particular, we propose the use of the Average Tax Progression Rate (TPPT per its acronym in Spanish), which is part of the World Tax Indicators base (Andrew Young School of Policy Studies, 2010). This is defined as the regression coefficient between average tax rates and different income levels, so its value is positively related to the tax progressivity degree.

However, the insufficient number of observations of this indicator for a country like Colombia, in addition to the multitude of control variables to be considered, makes any study based on temporary observations for the same unit unfeasible, which is why it is preferable to work with a data panel. The empirical work proposed here is based on a sample of around 138 nations (including Colombia) and 40 years (1976-2015 period). It should be noted that in the case of the TPPT, there are discontinuous observations between 1981 and 2005, which in addition to the loss of data for institutional variables such as the Government Quality Index (constructed by the Political Risk Service group) justifies the imputation of data.

In particular, multiple imputation (IM) is applied, a method that replaces missing data through a stochastic process wherein a set of “complete” variables is defined, or with as many observations as possible (e.g. GDP per capita), and after several rounds (in this case 30) different imputed bases are constructed, which replace missing data with probable values in order to combine them and calculate an mean estimator and a standard error (Rubin, 1996). Ultimately, after applying IM, the number of observations increased significantly, from an average of 9 to 32 per country.

Table 5 briefly presents the set of variables considered in this section, together with the description of each one, the sources of information and finally the expected sign of the respective associations. It is worth mentioning that the selection of the variables that appear in this table is based on a review of the literature specialized in the subject, in which various determinants of taxation related to economic, social, cultural and political issues are studied. Among the works consulted are: Castañeda-Rodríguez (2014 and 2018), Profeta, Puglisi, and Scabrosetti (2013), Angelopoulos, Economides, and Kammas (2012), Dioda (2012), Broms (2011), Bird, Martínez-Vázquez, and Torgler (2008), Mahdavi (2008), Gupta (2007) andPiancastelli (2001).

Table 5 Description of the variables used in the study

| Variable | Description | Expected Correlation | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collections | Total tax burden (% GDP). | NA | United Nations University (2017). |

| Rec_ISR | Revenue from ISR (% GDP). | NA | |

| TPPT | Average Tax Progression Rate. | ? | Andrew Young School of Policy Studies (2010). |

| Log_GDP_per | Logarithm of GDP per capita measured in constant United States dollars (base year = 2000). | + | WDI |

| %Trade | Sum of imports and exports (% GDP). | ? | |

| %Agriculture | Share of the agricultural sector in the economy (% GDP). | - | |

| Inflation | Percentage change in consumer price index (%). | - | |

| Serv_Debt | Public debt service (% GDP). | + | |

| Rentas_naturales | Public revenue attributable to the exploitation of natural resources (% GDP). | - | |

| Education | Standardized years of education per capita. | + | IHME |

| Density | Logarithm of the number of persons per square kilometre. | ? | WDI |

| %Pop_Urb | Urban population (% total population). | ? | |

| %Pop_65 | Population over 65 years (% total population). | + | |

| %women_lab | Participation of women in the labor force (%). | + | |

| Quality of government | Indicator that considers three factors: (1) corruption, (2) law and order, and (3) quality of bureaucracy. Their values are between 0 and 1; it is directly related to the level of quality of government. | + | ICRG |

| Democracy | Democratic level measured in the range [0, 10] (0 is less democratic and 10 more democratic). | + | Freedom House |

| Left | Fictional variables indicating whether a government can be ideologically characterized as left-wing or center-based, as well as whether there are elections in the executive respectively. | ? | DPI |

| Center | ? | ||

| Elections | ? | ||

| English | Fictional variables that refer to the legal origin of trade law in each country. The reference category in the Socialist/Communist code. | + | La Porta, López de Silanes, Shleifer, and Vishny, (1999). |

| French | |||

| German | |||

| Scandinavian | |||

| General | Dummy equals 1 (0) if the fiscal statistics correspond to the level of general (central) government. | + | United Nations University (2017). |

Notes: WDI (World Development Indicators-World Bank); IHME (Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation-University of Washington); ICRG (International Country Risk Guide); DPI (Database of Political Institutions- World Bank).

Source: Author’s own elaboration.

It is important to note that in some cases a question mark appears in Table 5, which indicates that although the respective variable can be theoretically associated with Revenue or REC_ISR, the empirical evidence is not conclusive. For example, in the case of population density, some authors argue that it reduces tax costs and thus contributes to increasing the tax burden (Diode, 2012), although it is also possible that greater concentration of taxpayers in a given area will generate economies of scale in the provision of public goods and reduce funding needs (Alesina and Wacziarg, 1998).

With regard to estimates, it should be mentioned that static models with fixed and random effects are the most common, although in addition to validating the choice between them, it is essential to contrast hypotheses such as homoscedasticity and non-serial or contemporary correlation. On the other hand, the Breusch and Pagan multiplier test and the F test showed that either model was preferable to pooled data4, although the Hausman test tilted the balance in favor of fixed effects. In relation to the basic assumptions about errors, heteroscedasticity, as well as serial and contemporary correlation issues were identified through the modified Wald tests, Wooldridge autocorrelation and Breusch-Pagan independence tests (Table 6). Therefore, and in order to address the difficulties posed by these findings, we chose to apply the Panel Corrected Standard Errors (PCSE) technique.

Table 6 Rigor tests on the errors in the fixed effects model

| Dependent Variable | Collections | Rec_ISR |

|---|---|---|

| Hausman Test | 0.001 | 0.000 |

| Wooldridge test for autocorrelation | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Wald Modified Test for heteroscedasticity | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Breusch and Pagan Test for Contemporary Correlation | 0.000 | 0.000 |

Source: Author’s own elaboration.

On the other hand, it is also true that revenue can not only be affected by exogenous factors, such as the economic cycle, but also seems to depend on the past or trajectory (Gupta, 2007), suggesting that dynamic models be considered in the empirical exercise. Therefore, the Generalized Moments Method -MMG (Arellano and Bover, 1995) was adopted, which works with equations in levels and uses the difference in the lagging dependent variable as an instrument for estimation. In addition to the total tax burden, the collection of the ISR was taken as an endogenous variable, due to the concerns suggested by a highly progressive regime for people with greater capacity to pay. At the end, four models were estimated, two applying PCSE and the other two using MMG (Table 7).

Table 7 Estimates static and dynamic models

| Method | PCSE | MMG | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | Collections | Rec_ISR | Collections | Rec_ISR |

| Lagging Dependent Variable | 0.049 | 0.134 | ||

| TPPT | 22.629*** | 18.494*** | 44.538** | 46.323*** |

| Log_GDP_per | -0.569** | 0.332** | -0.969* | -0.017 |

| %Trade | 0.018*** | 0.005*** | 0.017** | 0.005 |

| %Agriculture | -0.151*** | -0.042*** | -0.158*** | -0.040** |

| Inflation | -0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Serv_Debt | 0.016 | -0.008 | 0.013 | -0.021 |

| Rentas_naturales | -0.048*** | 0.012 | -0.049 | 0.014 |

| Education | 0.431*** | 0.161*** | 0.352* | 0.168* |

| Density | -0.832*** | -0.473*** | -0.675** | -0.376** |

| %Pop_Urb | -0.064*** | -0.018*** | -0.050** | -0.005 |

| %Pop_65 | 0.357*** | 0.150*** | 0.307* | 0.045 |

| %women_lab | 0.096*** | 0.067*** | 0.086*** | 0.060*** |

| Quality of government | 4.421*** | 3.137*** | 4.140** | 2.679*** |

| Democracy | 0.157*** | 0.031 | 0.137 | 0.006 |

| Left | 0.397 | 0.165 | 0.306 | -0.005 |

| Center | -0.314 | -0.194 | -0.496 | -0.242 |

| Elections lag | -0.002 | -0.043 | -0.055 | -0.058 |

| English | 1.745*** | 2.403*** | 1.412 | 1.851*** |

| French | 1.720*** | 1.464*** | 1.578 | 1.311** |

| German | -1.231 | 1.205** | -1.231 | 0.950 |

| Scandinavian | 9.406*** | 6.532*** | 9.405*** | 5.358** |

| General | 1.113** | 0.720*** | 1.599* | 0.818* |

| Constant | 13.844*** | -2.614** | 15.734*** | -0.984 |

| Observations | 4382 | 4252 | 4404 | 4260 |

Source: Author’s Own elaboration.

It should be noted that our two endogenous variables apparently do not depend on trajectory, judging by the statistical significance of their lags in the estimates from Table 7. This suggests, thence, that taxes respond significantly to exogenous shocks (e.g. socio-economic changes). However, in general, there is little change in the results between static and dynamic models, in addition to the fact that most of the predictions suggested by the previous literature (Table 5) are corroborated.

Before reviewing the coefficients associated with TPPT, it should be noted that our results also shed some light on those variables whose relationship with revenue is not clear, considering the respective empirical literature. For example, Table 7 supports what Alesina and Wacziarg (1998) suggested, as population density and percentage of urban population seem to favor a more efficient public provision of goods and services and consequently a lower demand for financing. On the other hand, the ideological orientation of governments or post-election periods have no impact on tax matters, which implies that administrations tend to be pragmatic when it comes to economic decisions (e.g.,Castañeda-Rodríguez, 2014).

Now, in relation to the variable of interest, namely TPPT, it should be noted that any of the models presented in Table 7 identifies a positive association between it and total revenue or per ISR only. That is to say that instead of the progressivity of the tax system meaning less revenue, due to the economic distortions that the former represents, empirical evidence suggests that the association is positive, which could be explained through the literature on tax morality. In fact, progressivity facilitates the state-society relationship to be regarded as fair by citizens, making the collection of taxes legitimate and thus reducing the natural resistance to paying them (Doerrenberg and Peichl, 2013). In fact, and according to Graphs 5 and 6, developed countries collect more than other developing countries such as Colombia, precisely because the ISR plays an important role in their tax systems, a tax that also has the most redistribution potential.

Although the above suggests the possibility of being faced with a problem of endogeneity or causality reversal, since high revenue (particularly due to the ISR) could also affect the degree of progressivity of the tax system; empirical evidence discards this possibility. In this regard, some intermediate models were considered wherein TPPT was instrumentalized through other factors such as the amount of income from donations or international assistance, but after verifying the validity of the instrument it was concluded that there was no evidence of the problem (using the Hausman test for diagnosis). Due to space, the respective models were not presented, although they are available upon request to the author.

All of the above presupposes that a tax reform can be thought, which, in addition to increasing the revenue, is progressive, exploiting the potential of unused sources such as the ISRP. However, for this to be done, it is essential to undertake actions that improve the institutional capacity of entities such as DIAN, so that all taxable persons,as defined by law, become aware that they can be identified by the administration if they do not effectively comply with their formal and substantial obligations. It should be noted that although the issue of modernization of the DIAN was considered by Act 1819 of 2016 in part XIV, its implementation is lagging behind.

5. Conclusions

The latest tax reform in Colombia was presented as structural, comprehensive and progressive, but a review of what was finally approved in Act 1819 of 2016 allows us to establish that these qualities remained only in good intentions. It cannot be said that this reform has been structural since it did not address the study of public expenditure, a task that was assigned to a new commission (Article 361 of the Act). On the other hand, a reform that does not delve deeper into the problems of subnational taxation is not comprehensive, nor is the reform that bases most of the increase in revenue on increasing the general VAT rate. In fact, in the short term there is a need for a new reform for fiscal purposes, as evidenced by the reports of several risk-rating companies such as Fitch (2018).

Although the diagnosis the Comisión de Expertos para la Equidad y la Competitividad Tributaria (2015)used is correct and has technical support, judging from previous work on the subject, what was finally implemented has a limited scope. Although Act 1819 of 2016 managed to incorporate some adjustments that go in the right direction, such as the unification of ISRE and CREE or the revision of the purging of the ISRP model, they coincide with a series of errors or other modifications that hinder the fulfillment of the aims pursued, what was called counter-reforms here.

For example, while the schedular income model sought to limit certain tax benefits and tax some income, in the case of dividends and shares filed as INCRNGO under Articles 48 and 49 of the ET, the failure to incorporate any control to correct the effect of the division of total income means the risk that many taxpayers are not taxed with a tax commensurate with their capacity to pay. This is precisely evident in the case raised after Table 4.

The logic behind the IMAN and IMAS was precisely to set a minimum, which raises questions regarding the progressivity and efficiency of the ISRP for not being present in the last reform. Nor is it clear to what extent does Act 1819 of 2016 simplifies the national taxes system, given that there are rules whose regulation by itself involves a complex calculation (e.g. the comparison between net income and presumptive income according to Decree 2250 of 2017).

Beyond the fact that the latest tax reform does not meet the objectives it initially sought, something worrying is that now we must think of a new adjustment to the rules of the game in this area, based on the pronouncements of entities such as Fedesarrollo, or risk raters such as Fitch. This not only creates uncertainty and hinders the full compliance of tax obligations, but also indicates that real solutions to the endemic and over-diagnosed problems of the Colombian tax system have not been implemented.

In this scenario, there is a need to incorporate new contributors, particularly with regards to ISR. It cannot be expected that the greatest fiscal effort will continue to be made by taxable entities who are already identified by DIAN, the case of large taxpayers and workers in the formal sector, but a structural reform must rethink the role of direct taxes. While some refuse such measures on the grounds that ISR has significant distortive effects that can lead to abrupt changes in tax bases, international comparison shows that most developed countries rely largely on sources such as ISRP. In fact, the literature on tax morality indicates that features such as horizontal and vertical equity are not only desirable, but also help reduce evasion. Moreover, the empirical findings shows that greater collection and progressivity are not antagonistic purposes, since they are positively correlated (Table 7).