1. Introduction

Act No. 1314 of 2009 empowers the State under the leadership of the President of the Republic to intervene in the economy, to limit economic activity and, through regulations, issue norms to obtain financial information that is understandable, transparent, comparable, relevant and reliable, useful for decision making in benefit of the State, investors, creditors, workers and society itself. This purpose has been materialized through regulatory decrees; it is necessary that the addressees know and apply the rules appropriately.

To contribute from a legal perspective, two objectives are proposed: the first is to establish, from theory and doctrine law and jurisprudence, the legal nature of the regulatory framework, consisting of Act 1314 of 2009 and the decrees that develop it. While it is true that IFRS include IAS, IFRS, IFRS for SMEs and technical framework for microenterprises, this paper refers in particular to IAS and IFRS, by making an approach to their structure as a principled model, closing with the description of the rules for interpretation applicable in the Colombian context. The second one will be to analyze in a simple random sample of concepts issued by the CTCP during the period 2013-2018, the observance to the rules of interpretation and evidence if there are gaps or normative conflicts.

2. Nature and legal structure of FRS

In this section, from the legal theory, two relevant aspects are developed: (a) establishing the legal nature of Act 1314 of 2009, and (b) making an approximation to the structure of the normative framework.

2.1. Legal nature of Act 1314 of 2009

The State, through this law, ordered the intervention of the economy. Then, with Act 1450 of 2011, or National Development Plan, sought its consolidation to guarantee the resources and institutional integration necessary to achieve its objectives, which resulted in the issuance of Accounting Standards, Financial Reporting and Information Assurance, and other provisions were issued through decrees, compiled later in the Single Regulatory Decree 2420 of 2015. This process was sponsored or promoted by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the Financial Stability Board (FSB), the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB), and bodies such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (WF - IMF) (2003).

The purposes of Act 1314 of 2009 are summarized in: (a) intervention of the economy by the State; (b) contributing to the internationalization of economic relations; (c) providing useful information for decision-making, particularly for the market, investors, lenders and other users; and (d) legal certainty through regulations, issuance of accounting standards, financial reporting and information assurance as a single, homogeneous, high-quality, comprehensible and enforceable system, with one particularity: converging with internationally accepted standards.

Because of its characteristics, this Act is part of the paradigm of regulatory law, which, in terms of Nonet and Selznick (2017), cited in Calvo, 2005, is understood as an evolutionary state of law, characterized by serving as an instrument to address social needs and requirements, aimed at making effective State intervention policies. According to Calvo (2005), “this useful law or regulatory law is characterized by being deeply penetrated by criteria and determinants of a material nature: economic, political, axiological, technical, etc.” (p. 10). To this type belongs Act 964 of 2005, analyzed by Blanco and Castaño (2006), and Act 1341 of 2009, revised by Montes (2014).

Act 1314 of 2009 in encompassed in regulatory law, the intervention of the State in the economy and the law as an instrument to achieve the aims of the State. The lawmaker sets criteria and objectives to be developed by the executive through regulatory power, pursues a dynamic law according to the requirements of the market, thus incorporating a new regulatory framework based on principles, on the context of globalization, on the protection of investors and lenders and a basic requirement: legal certainty. A type of law that, in terms of Vera (2000), “is the great instrument that the social community has for its self-control, sooner or later it will have to internationalize in order to generate increasingly necessary Macro Legal Security” (p. 19). This is the Colombian case when it embraced international standards, following the parameters of Act 1314 of 2009.

Regulatory law, an expression of state intervention in the economy, requires not only the issuing of a set of rules, but its realization requires implementation. This term arose from the publication by Pressman and Wildavsky (1998), and according to Calvo (2005) it consists:

Firstly, [in] the creation and implementation of the legal and bureaucratic framework for intervention that assumes the development of programmes and implementation of regulations for the protection and promotion of social values and purposes, which require increasingly complex regulation and the “mobilization” of broad economic and institutional means; technical and human resources necessary for the achievement of regulatory objectives and purposes: budgetary allocations; design and promotion of public policies and intervention programmes; creation or adaptation of public and semi-public intervention apparatus and infrastructure; incorporation of experts; establishment of controls and evaluations, etc. (p. 33).

In Colombia, for the complex process of implementing Act 1314 of 2009, together with the provisions of Act 1450 of 2011, responsibilities have been assigned, coordination between sectors involved and provision of human, technical and scientific resources. The results are yet to be evaluated and their examination does not fall within the scope of this work. To that end, studies such as those carried out by Blanco and Castaño (2006), Peña (2011) and Revuelta (2007) will have to be followed.

Act 1314 of 2009 and the decrees implementing it must be seen as a set, guarantee legal certainty, and meet two requirements: validity and effectiveness. Legal certainty is one of the aspirations of man; it is part of the transition from the government of men to the government of laws (the rule of law, defined by Hayek, 2008). For Hobbes (2001), it is the link between the State and the Law, for his part, Guastini (2015) “commonly understands [as] the possibility of each to foresee in advance the legal consequences of his actions. This, in turn, obviously implies knowledge of the law in force” (p. 19). Legal certainty is more than a concept; it is an integral part of the law itself. Radbruch (1997) conceives it as a third element of the idea of law, and restricts it to the security of the law itself, which demands that it: (a) be positive (legal norms); (b) be based on facts and not refer to value judgments in the specific case; (c) the facts can be established with the least margin of error, i.e., “practicable’; and (d) not be exposed to changes too frequently, or at the mercy of incidental legislation. On the other hand, Ávila (2012) ties the concept of legal certainty to the ideals of determination, stability and predictability of law.

The guarantee of legal certainty, which derives from the incorporated standards, i.e. international standards, appears to be, at least formally, the claim of IASB (2012), in setting the procedure for issuing standards, as stated in paragraphs 17 and 18 of the Foreword to IFRS; and in Colombia, with the process adopted by the CTCP pursuant to article 8 of Act 1314 of 2009.

Bobbio (2012) builds the validity thereof in three operations: (a) determine whether the authority that promulgated it has legitimate power to issue legal rules, (b) check if it has not been repealed, and (c) check that it is not incompatible with other rules of the system. Requirements met, subject to constitutional review by the Constitutional Court and the Council of State, the actions against them have not been successful. As an example thereof, the Constitutional Court, in Decision C-1018 of 2012, declared article 4, paragraph 1, of Act 1314 of 2009 enforceable. Regarding effectiveness, Bobbio (2012) notes:

The problem with the effectiveness of a rule is whether or not the persons to whom it is addressed comply with the rule (the so-called addressees of the legal rule) and, if it is violated, whether it is enforced by coercive means by the authority, which has imposed it. (p. 22).

Effectiveness, in the case of IFRS, is a requirement; knowledge of the standard, its nature, structure and methods of interpretation is required for this purpose.

2.2. Legal structure of the FRS

Decree 2420 of 2015 compiled the regulatory framework issued in compliance with Act 1314 of 2009, which consists of two books: the first one contains the regulatory scheme of accounting, financial reporting and information assurance rules; the second one, the final provisions. Furthermore, the first book consists of two parts: the first one includes accounting and financial reporting standards (FRS), which correspond to the adoption of IAS, IFRS and IFRS for SMEs, and a technical policy framework for microenterprises based on IFRS for SMEs and the document prepared by the ISAR Group of the Conference of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). The second half relates to Information Assurance Standards (IAS), which adopt International Standards on Auditing (ISA), International Quality Assurance Standards (IQAS), International Standards for Revision Work (ISRW), International Standard on Assurance Engagements (ISAE), International Standards for Auditing Related Services (ISARS) and the Code of Ethics for Public Accounting Professionals.

Recognizing the basis of the model has implications for its interpretation, decision-making and setting of accounting policies, where a key element is the Conceptual Framework for Financial Information, updated by the IASB (2018), the purpose of which, among others, is to help develop new standards. From the theory of law, the debate was opened around rules, trying to distinguish between rule and principle. To that end, Atienza and Ruiz (1991) use the terms “rule” and “principle” as species of the genus “norm”. Dworkin (2013), for his part, defines principle as “a standard that must be observed, not because it favors or ensures an economic, political or social situation that is considered desirable, but because it is a requirement of justice, equity or some other dimension of morality” (p. 72). In the same sense, Alexi (2003) conceives principles as optimization mandates that can be fulfilled to varying degrees according to legal possibilities, while rules are final mandates.

Ávila (2011) identifies differences between rules and principles: (a) by their descriptive nature: rules describe determinable objects (subjects, behaviors, matters, sources, legal effects, contents), whereas principles describe an ideal state of things to be promoted; (b) by the nature of their justification, a requirement for be applied: rules demand an examination of correspondence between the normative description and the acts practiced or events occurred, while principles require an assessment of the positive correlation between the effects of the adopted conduct and the state of affairs to be promoted; (c) by the nature of the contribution to the solution of a problem, rules are intended to decide, as they seek to provide a provisional solution to a known or foreseeable problem, whereas principles are intended to complement, since they function as reasons that combine with others to solve a problem.

While the difference between principle and rule seems clear, in practice, as far as FRS are concerned, it is not. It was not at first an exhaustive conceptual statement. Túa (1985) concludes the presence of principles from norms, as in IAS 1, which recognizes three principles: continuous management, continuity and accrual; and three key practices or factors in determining or choosing accounting policies: prudence, priority of substance over form and relative importance. These principles and factors were expected to be used by the International Accounting Standards Committee (IASC) in the 24 International Accounting Standards (IAS) issued up to 1985. In this regard, Marcotrigiano (2017) concludes that financial reporting standards constitute a “principled model that contains specific accounting rules, both principles and rules being necessary to carry out the regulatory process in an international accounting environment” (p. 241). For their part, Cañibano and Herranz (2013) emphasize the importance of applying accounting principles that inspire the IASB, rather than detailed rules, the faithful image as a macro-principle that has permeated the accounting directives of the European Union, the economic fund and the professional judgment.

The debate on a principle/rule-based model has also been the subject of study in the United States. Schipper (2003), a member of the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB), argues that this country’s Financial Reporting Standards are based on principles derived from the FABS’s conceptual framework and that a principled model, requiring scope exceptions, needs rules, and that perhaps detailed implementation guidelines make standards seem rules-based. He concludes that the removal of principled guidelines and standards requires greater emphasis on professional judgment and this, in turn, requires training.

In Colombia, the Technical Council of Accounting, in its Pedagogical Guidance 012 (Bautista, Molina, and Zamora, 2015), echoes the declaration of a model based on principles, from the transition from formalism to anti-formalism, where the conceptual framework is crucial for the definition of the model based on principles. Previously, as Túa (1985) warns, principles used to underlie the standards; now, with the approval and implementation of the conceptual framework, the objectives and qualities of financial reporting became the foundation. Thus, the conceptual framework meets, following Avila (2011), the pretense of complementarity, a characteristic of principles. From a model based on principles or rules, consequences arise in the professional practice (Molina and Túa, 2010), given the pretense of legal certainty, a model based on specific rules and interpretation guidelines is preferred by preparers, auditors and users; a model based on principles, which requires professional judgment, is the preference of academics and those with greater experience and knowledge on standards. In the training, Drnevich and Stuebs (2013) demonstrate the influence of culture when applying FRS.

3. Interpretation as an awarding-application problem

This section seeks to identify existing resources in the Colombian legal system for the interpretation of FRS.

3.1. General considerations

The law is interpreted, in this case, the FRS. The CTCP, considering the approach of the IASB (Bautista et al., 2015), exposes what would be the deductive logical itinerary based on the conceptual framework, the ideal to be achieved, the obtaining of useful information for decision-making by the user and the objective: to decide the applicable standard. This itinerary involves: (a) understanding of the economic and financial effects of the transaction, (b) an analysis of the transaction based on the conceptual framework (decisions on recognition, measurement, presentation and disclosure); (c) determining the applicable standard; and (d) an analysis of the reflection in financial reports. This paper emphasizes the literal c.

Following Kelsen (2009), the rules in general are observed to incomplete, there is deliberate indetermination by the lawmaker when incorporating options and ambiguity in the use of words or sequence of words, and contradictions between rules, or lack of an applicable rule. FRS, as part of the legal system, suffer from these indeterminations, and it is likely that there will be more than one applicable rule (IAS or IFRS contained in the decrees), or that, while applicable, may be inconvenient or contradict a principle. There is no unsolved case; the law must guarantee legal certainty, which translates into certainty and predictability, or assurance of guidance. In this sense, García (2000) points out that “the fullness and precision of the norm will require that the position of such a norm in relation to the others respond to an order” (p. 80), and such an order is provided for by the very law. In this regard, the Ministerio de Justicia y del Derecho y la Escuela Judicial Rodrigo Lara Bonilla (Ministry of Justice and Law and the Rodrigo Lara Bonilla Judicial School) (1988) state that the interpretation system in Colombia is regulated, which means that the guiding principles for interpretation are found in the law. This provision prevents arbitrariness.

3.2. General rules for interpretation

Interpretation, for Savigny (1878 trans. in 2004), is “the reconstruction of the thought contained in the law. Only by this means can we reach true and comprehensive knowledge thereof and be in a position to fulfill the object proposed by it” (p. 149). For this purpose, the author distinguishes four constituent elements: grammatical, logical, historical and systematic. These kinds of interpretation or methods, which can be called classics, have permeated Colombian legislation. The Civil Code of the United States of Colombia (1873), in its preliminary title, chapter IV, establishes rules for interpreting the law. These are general rules, mandatory and complementary to those incorporated in the FRS. In the Civil Code, two types of interpretation are distinguished, aimed to the subject who interprets: (a) the lawmaker: article 25, which uses as an interpretative remedy the promulgation of another rule to determine the meaning of the former; and (b) doctrinants: article 26, which includes judges, officials and individuals; the latter as long as they refer to their facts and interests. Doctrinants subject to the rules laid down in articles 27 to 32 of the Civil Code, which consider: (a) to be tempered to the meaning of the law when it is clear, that is, to its literal meaning; (b) to understand the meaning of the words in their natural sense, except in case of a legal definition; (c) to take the technical words of all sciences or arts in the sense given to them by those who profess the same science or art, unless it appears clearly that they have been formed in a different sense; (d) interpret the law in context, using the analogy as a resource; (e) illustrate the meaning of each of the parts of the law, so as to ensure proper correspondence and harmony among all of them; and (f) using the general principles of law.

The rules provided for in the law are complemented by jurisprudence, in Judgment C-054 of 2016, the Constitutional Court synthesizes the methods in: (a) systematic, considers the body of law as a system; (b) historical, seeks meaning in the background and preparatory works; (c) teleological, investigates the purposes of the lawmaker; and (d) grammatical, seeks the infallibility of the lawmaker, since it assumes that, in certain cases, the rules have only one meaning that does not need to be interpreted. Adding thereto is the analogy of the rules where to FRS resort as a mechanism for the integration of law, recognized in article 1 of the Commercial Code. In jurisprudence, Decision C-083 of 1995 by the Constitutional Court, it states: “Where there is no exactly applicable law to a disputed case, the laws governing similar cases or matters shall apply and, failing that, constitutional doctrine and general rules of law.” From the doctrine, for Atienza (1985) the analogy contributes to solving basic problems in any legal system, while preserving its structure; in other words, “the reduction of the complexity in the social environment by allowing the adaptation of a system consisting of a set of fixed rules to an environment in constant transformation” (p. 224).

3.3. Hermeneutical Considerations in FRS

FRS have three peculiarities: the first one is the process followed by the IASB to issue a standard; it provides for three years, from the initiative to the issuance of a new standard or the modification of an existing one, and opens a public debate, giving rise to the belief that one of the requirements referred to by Radbruch (1997) is met, in terms of not being subject to permanent and incidental modifications. The second one is that each FRS (IFRS-IAS) has its own and homogeneous structure and consists of: (a) objective; (b) scope; (c) definitions; (d) recognition and measurement; (e) disclosures; (f) effective date and transition; (g) derogation of other pronouncements; (h) appendix with illustrative examples; and (i) complements as guidelines for implementation, foundations of conclusions and interpretations, which gives the impression of integrity. Harmonized structure with the rules and methods of interpretation provided for in the Codes and case law.

The third feature of IFRS (-IAS-IFRS) is the inclusion of their own rules for interpretation. To demonstrate these, reference is made to Annex 1 to Decree 2420 of 2015, in particular to IAS 1, IAS 8 and the conceptual framework that gives the model character under principles and serves to fill normative gaps and conflicts between rules or between principles and rules. The review is not exhaustive, but we cite those considered key:

Demand for faithful image. Prevalence of the principle, i.e. the purpose to be achieved, as provided for in paragraph 15 of IAS 1, subject to definitions and recognition criteria established in the conceptual framework. The rules of articles 28 and 29 of the Civil Code and the teleological method are applied, with the aim of achieving the faithful image as an objective to provide useful information in decision-making.

Absence of an applicable rule. According to paragraph 10 of IAS 8, the judgment of Management is required. The criterion address the vacuum is the qualitative characteristics of financial information: relevance and reliability. For this judgment, the sources set out in paragraph 11 of the same standard shall be used in descending order, i.e. (a) the requirements of IFRS dealing with similar and related topics; and (b) the definitions, recognition and measurement criteria set out in the conceptual framework; and, according to paragraph 12 of IAS 8, it is possible to resort to pronouncements by other issuers of standards, accounting literature (doctrine) and practices recognized by sectors of the same activity, provided that they do not conflict with the conceptual framework, practice of the systematic method, is decided by analogy and objectives defined in the conceptual framework.

Conflict between principles and rules. Paragraph 19 of IAS 1 considers the possibility for Management to conclude that the application of an IFRS requirement (rule) would be misleading and would conflict with the purpose of the financial statements set out in the conceptual framework (principle). In order to decide, two options are envisaged: (a) according to paragraph 20, the entity will not apply it, provided that the regulatory framework requires, or does not prohibit, this non-application; (b) according to paragraph 23, if the regulatory framework prohibits separation, i.e. non-application, the requirement is applied, but reducing, to the extent that it is possible, non-compliance aspects perceived as causing deception. In both cases, the entity shall disclose the reasons, either for departing or for applying the requirement, and how the misleading aspects are reduced. The method is teleological, that is, the principle prevails.

In short, the structure of FRS and the general and specific rules for interpretation, together with the due process model, the basis for the issuance of standards by the IASB, adopted in Colombia, generate elements aimed at providing legal certainty, a premise of the idea of law proposed by Radbruch (1997).

4. Methodology

This research was based on the concepts issued by the CTCP for the period 2013-2018. The sample was selected under the simple random method, and categories and variables were defined for the analysis of results.

4.1. Preliminary assessment of progress in the interpretation of FRS in Colombia

In the notes to the financial statements, entities, in accordance with paragraph 16 of IAS 1 incorporated in Single Regulatory Decree 2420 of 2015, are required to make “an explicit and unqualified statement” indicating that they comply with the FRS. This means that the law in force is well known, that the rules have been interpreted, applied fully and that, if professional judgment is required, they have considered, among other aspects, the rules of interpretation provided for in the Colombian legislation. This declaration aims to generate confidence, overcome the reproach that was made at the time about the shortcomings of accounting standards, the existence of various sources, as did the ROSC 2000 report, and the evidence on accounting manipulation (Elvira and Amat, 2007), taking advantage of, among other factors, ambiguity and regulatory gaps. The CTCP, as the Technical Standardization Agency, has the legal power to absolve queries concerning the interpretation and application of regulatory technical frameworks for financial reporting and information assurance. The structure of consultations and concepts allows to make a preliminary assessment of the state of FRS interpretation, for which purpose the analysis of a sample of concepts issued by the CTCP is made.

4.2. Sample

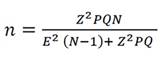

The population was composed of the concepts issued by the CTCP in the period 2013-2018, available on the website of the entity, cut-off to 22nd December 2018. The total number of concepts issued was 5408. The sample (n) was obtained using the simple random sampling method, at 95% confidence rate and an error margin of 5%, using the expression:

Where: P: positive variability 0.5, Q: negative variability 0.5, Z: 95% confidence level, E: 5% error margin, N: population size = 5408

The sample size was made up of 359 concepts. To determine which concept to evaluate, a random selection procedure was used.

Table 1 shows the final conformation.

Table 1 Sample Composition of concepts issued by the CTCP period 2013-2018

| Year | N° Concepts | Consultant | Query Type | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accountant | Others | FRS | Missing C | Others | ||

| 2013 | 24 | 15 | 9 | 10 | 2 | 12 |

| 2014 | 54 | 31 | 23 | 26 | 6 | 22 |

| 2015 | 81 | 40 | 41 | 50 | 9 | 22 |

| 2016 | 69 | 35 | 34 | 39 | 5 | 25 |

| 2017 | 67 | 37 | 30 | 38 | 8 | 21 |

| 2018 | 64 | 26 | 38 | 21 | 15 | 28 |

| Total | 359 | 184 | 175 | 184 | 45 | 130 |

| Participation % | 51,3 | 48,7 | 51,3 | 12,5 | 36,2 | |

Source: Author’s own elaboration.

Taking into account the subject of study, the 184 consultations and concepts related to IFRS (IAS and IFRS) were analyzed.

4.3. Variables

The variables analyzed in this study were divided into three categories:

Type of consultant. Accountants and others. The latter included natural or legal entities other than public accountants.

Type of Query. Three types were defined: 1) referring to FRS, 2) lack of competence, and 3) other topics. The FRS queries were also classified into subtypes: a) according to complexity: general cases, the extent of the applicable standard, and difficult cases, when could there be a normative gap, a conflict between rules or between rules and principles. (b) According to structure: structured, when the consultant or the CTCP in its argument uses principles, rules or interpretation methods, either expressly or implicitly; unstructured, when the consultant asks the question indicating only the fact without invoking the applicable rule, or does not elaborate a possible solution to submit to the CTCP for consideration, or only refers to the standard that of which is looking for an explanation.

Type of Response. It’s the one offered by the CTCP. There are two types: (a) unstructured, where there is a rule applicable to the case, or it is a repeated concept to which the consultant is referred, or when the consultant referred to another entity for lack of jurisdiction; and (b) structured, where the rules for interpretation are invoked and implicitly or explicitly recognized in the text.

5. Results

The 184 concepts related to FRS were analyzed from two perspectives: the consultants and the CTCP (Table 2).

Table 2 Concepts issued by the CTCP during the period 2013-2018 related to FRS

| Type | Number of concepts | Consultation | CTCP Concept | Consultant | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structured | Unstructured | Structured | Unstructured | Accountant | Other | |||

| Difficult cases | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | ||

| General | 181 | 31 | 150 | 92 | 89 | 107 | 74 | |

| Total | 184 | 33 | 151 | 95 | 89 | 108 | 76 | |

| Participation % | 18 | 82 | 52 | 48 | 59 | 41 | ||

Source: Author’s own elaboration.

5.1. From the perspective of consultants

Consulting Subject . Public accountants made up 59% of the consultations. This may be due to the role played by this professional in the process of preparing, issuing, assuring and advising users of financial reports. 41% were raised by other type of consultants, such as managers, board members, co-owners and users of information. This indicates an interest in the proper interpretation of the rules. The common pattern was the search for legal certainty; the intention to ensure the applicable rule for each case. Informal consultations accounted for 82%. Now, while the same purpose, legal certainty, was pursued, the structured consultations representing 18%, reported a greater degree of elaboration, and in some cases were submitted a possible interpretation to consideration by the CTCP.

Regarding query types.

Difficult cases: Only 3 of the 184 concepts could be classified as difficult. They were characterized by the fact that the consultant considered that there was a vacuum, there was no specific standard (IAS or IFRS) and proposed an argument.

General cases. They were characterized by the fact that the consultant expected to obtain a clearly defined response in the legal system.

According to the research findings, it is not apparent from the text of the consultations, except for difficult cases, that the interpretation methods are explicitly resorted to, or that there is concern that the model is based on principles or rules.

5.2. From the perspective of the CTCP

The CTCP, by legal authorization, resolves any concerns raised to it for the proper implementation of the regulatory technical framework for financial reporting. It makes part of the strategy for implementing regulatory law and, although its concepts are not binding, they are authoritatively guiding and fulfill a pedagogical duty with a view to satisfying the requirement of effectiveness.

Regarding the types of response. Although, in the investigation, 82% of the consultations were not structured, the CTCP responded structurally by 52%, meaning that the CTCP not only refers to the applicable standard, but also guides by establishing the concordances and referrals it considers relevant.

Method. If interpretation in Colombia is regulated, it is expected that those who are empowered to resolve concerns about its application, such as the CTCP, will follow the recognized methods. To that end, although the method used by the CTCP is not expressed, it is inferred from the text of the concept, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3 Method inferred used CTCP

| Method | N° Concepts | Ratio % |

|---|---|---|

| Grammatical | 136 | 74 |

| Systematic | 30 | 16 |

| FRD | 1 | 1 |

| Not applicable | 16 | 9 |

| Analogy | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 184 | 100 |

Note: Not applicable refers to cases where a standard is not discussed.

Source: Author’s own elaboration.

As a general rule, 74% of the concepts use the grammatical method, i.e. it is limited to the text of the norm, thereby seeking to give meaning and scope, to frame the cases submitted for consideration within specific norms. 16% of cases use the systematic method, i.e. other provisions, to achieve the applicable standard. In two cases, the analysis differs. In one case it refers to the analogy and in the other, which corresponds to one of the cases classified as difficult, the CTCP resolves it by applying the rules of interpretation specific to the FRS; it uses the rules defined in IAS 8, paragraphs 10 and 11, and follows the provisions to follow in the absence of a specific applicable standard.

In all cases, the answer guides the consultant to a specific applicable rule; therefore, according to the sample, there would be no legal vacuum, indetermination, conflict between rules or between principles and rules. The picture is that, despite the recognition of a principled model, it is not evident in practice.

6. Conclusions

Act 1314 of 2009 is a manifestation of regulatory law, characterized by the economic, political and technical criteria that determine it. This Act empowers the State, under the guidance of the President and the competent authorities, to intervene in the economy and fulfil one objective: to issue accounting, financial reporting and information assurance standards, which serve to generate financial information useful in the decision-making of users and contribute to the integration of the Colombian economy into the global economic system.

Subject to the parameters established by law and in accordance with the regulatory powers granted by the Constitution to the President of the Republic, the corresponding decrees have been issued, compiled in Single Regulatory Decree 2420 of 2015. This decree incorporates the International Standards of Accounting, Financial Reporting and Information Assurance into the Colombian legal system.

With the adoption, international issuers are recognized and the procedure for the issuance of standards - as is the case with the declaration contained in the Foreword to IASB International Standards - is faced with a particular way of creating law, at least formally; it is publicly known, has global coverage, is participatory and subject to criteria and planning.

The CTCP, in its capacity as normalizer, following the mandate of Act 1314 of 2009, instituted a procedure similar to that of the IASB: due process, which consists in submitting to consideration the standards issued by the international issuer, generates space for discussion to conclude and submit draft decrees to regulators.

The way of constructing law, as instituted by the IASB and the CTCP, allows prior knowledge and possibility, at least formally, to participate in the norm creating process; it is oriented towards the ideals of determination, stability and predictability (Ávila, 2012), towards secure law (Radbruch, 1997).

One incorporated international standards, their qualities are assimilated, and the FRS are recognized by the doctrine as a principled model. The difference between these concepts is distinguished from the law, which makes the interpretative exercise more complex and professional judgment permeates legal knowledge. Despite this, after analyzing the concepts, the results suggest that the model is not yet perceived and there is an underlying conception of the model as based on rules. Now, the rules are implemented in context. Interpretation is regulated in Colombia, so both rules and methods must be considered when interpreting IFRS and when formulating accounting policies and resolving cases, particularly the difficult cases. The method used by the CTCP, as inferred from the concepts analyzed, is grammatical; the norm (rule) appears to suffice and subsumes the cases put to consideration. However, the prior knowledge provided by the due process followed by the IASB and the CTCP makes it possible to complement the interpretation from the teleological and historical methods.

Due to the results obtained from the sample for the period 2013-2018, it is advisable to strengthen the legal training of addressees, in particular public accountants, given their participation in the process of preparation, issuance and assurance of information. Similarly, it is recommended that the CTCP extend its interpretative framework of reference, thus carrying out pedagogical work.