1. Introduction

One of the fundamental concepts to understand trade policies is Integration. Balassa (1961) defines it as a process and a state of affairs, i.e., it goes beyond forms of international cooperation and trade relations. Economic integration is part of the trade policies adopted by countries to improve their comparative and competitive advantages. Latin American countries have been at the forefront regarding economic integration. The process had two stages: one is based on the ECLAC model based on protectionism and inward development; the other is the liberalization of the economy and open integration. In South America, the countries with the most intensified trade liberalization policies and integration agreements are Chile, Peru, and Colombia (Márquez, Florensa, and Recalde, 2015).

These trade policies adopted by Colombia, Peru and, Chile are very similar in their designs, but what is their impact on these countries’ results on international trade? The results made it possible to identify, within the different government plans, that the commercial policies and institutions created have been very similar. However, the results in international trade are dissimilar, because each country had its own dynamic to insert itself into an open economy. Attention is drawn to the need for export diversification in Colombia and to improving current and future integration processes. As Rajagopal (2007) states, the impact of economic integration has been extensively studied, however, there are a few studies available on economic and institutional reforms in Latin America (LA). This document intends to contribute to this knowledge.

2. Integration in Latin America

The theory of economic integration is a discipline inaugurated in the 1950s by Jacob Viner (Jedlicki, 2009). Some theories that support it are federalism, functionalism, and neo-functionalism, whose greatest exponent is Ernst Haas, and intergovernmental theory with Stanley Hoffmann. In the early 1990s, with the Maastricht Treaty, other approaches such as institutionalism, constructivism, post-functionalism, and neo-institutionalism arose. One of the great contributions to integration was Bela Balassa’s, who established six types of economic integration, which emerged in the 1970s in Europe, namely, Trade Agreements, Free Trade Areas, Customs Unions, Common Markets, Economic Unions, and total economic integration. LA has also been a pioneer in economic integration. It was conceived many years before the EEC (the precursor of the European Union, EU), and according to Briceño (2018, p. 50), “Latin America is one of the territories of the world where regionalism and regional integration have been promoted for decades.” It even has two schools of regional integration and regionalism.

The first one is characterized by its purely economic approaches and development policies, under the paradigm of the ECLAC model proposed by the ISI (Industrialization by substitution of imports) and providing industrial autarchism, seeking to “... accelerate its development by limiting imports to promote an industrial sector” (Obstfeld and Krugman, 2003, p.260). The second one represents the new regionalism with Juan Carlos Puig and Helio Jaguaribe enacting regional autonomy as a broader strategy for international integration, while at the same time seeking to consolidate the internal governance capacities of states (Briceño, 2018). It is a type of integration based on open regionalism and compatible with the openness policies in the so-called “Washington Consensus”.

Firstly, the Montevideo Treaty stands out, which gave rise to the Latin American Free Trade Association (ALLAC), whose members were Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay and, Venezuela. This was the primary regional body to seek a free trade area, which was replaced by the Latin American Integration Association (LAIA) in 1980. The Caribbean countries did not wish to be part of the ALLALC and created, in 1973, the Caribbean Community (CARICOM).

In 1969, the Andean Pact was born as a sub-regional alternative, which sought to integrate similar economies such as Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru. In 1992, the Andean Group established the Free Trade Area and succeeded in adopting a Customs Union in 1995. That year the Presidents agreed on the restructuring of the institutions and bodies of the Cartagena Agreement and their articulation into an Andean Integration System. In 1996, the Andean Community of Nations was created to achieve advanced and deeper integration. In 1997, Peru assumed full membership, while Venezuela withdrew in 2006, and Chile returned after 30 years.

One of the most ambitious integration projects was the Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA) promoted by the United States, which was signed in 1994 as a multilateral free trade agreement covering all the countries of the Americas, except Cuba. The FTAA was supposed to take off in 2005; however, the would-be member states went into a crisis that year and it is considered a non-achievable project nowadays. On the other hand, at the beginning of the 21st century, south-north integration agreements with the United States and the European Union (EU) increased, and Asian markets gained major relevance, particularly China.

The regional integration crisis and the ‘open regionalism’ model coincide with a new wave of proposals, all of which point to the redefinition of integration, to wit, The Peoples´ Trade Treaty (ALBA-TCP). It was initially promoted by Cuba and Venezuela and was enacted in 2004. Another opposition project is the South American Community of Nations (CSN per its acronym in Spanish), which originated in 2004. Subsequently, in 2007, this led to the formation of the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR) in 2011. Malamud and Gardini (2012) argue that Latin American attempts to regionalism ended in separate blocs, with several overlapping projects in coexistence. Despite the criticism to open integration, most South American countries have signed between 10 and 19 agreements, mostly trans-regional agreements involving intraregional partners such as the United States, Europe, and Asia. Colombia, Peru and, Chile were influenced by the paradigms established by supranational organizations more than other countries in South America.

2.1. Studies on Economic Integration in Latin America

According to Axline (1981) , in the 1960s, the most prominent studies on Latin American integration were based on the neo-functionalism theory. Although, for example, Haas (1967) had to modify the neo-functionalism theory in his publication “The union of Europe and the union of Latin America”. In recent years, there have been several studies based on integration in LA, with widely dispersed approaches. Some authors have focused on analyzing the impact of economic integration based on Mercosur (Kaltenthaler and Mora, 2002; Rajagopal, 2007; Kennedy and Beaton, 2016; Campos, 2016), the Pacific Alliance (Mora, 2016; Seatzu, 2015), the Central American Common Market, the Latin American Free Trade Area, and the Andean Pact (Brada and Mendez, 1985).

Different authors have focused on critical integration studies. Genna and Hiroi (2004) argue that integration is more likely to take place when the relative economic power of the integrating states is asymmetric, and they share common elements such as an economic policy, whereas Genna (2010) argues that MERCOSUR can refuse the biggest economic stakeholders on account of economic disadvantages and limited access. Conversely, China is rapidly growing and offers a more attractive market for exports. In this vein, Shadlen (2008) examined the export profiles of LA countries and demonstrated that the power asymmetries between LA and the United States affect the preparation of national trade policies. Comparative analyzes have also been conducted. For instance, De la Llosa (2016) draws a parallel between European and Latin American integration and states that regional groupings transfer European models rather than copying them. Meanwhile, Reyes, Schiavo, and Fagiolo (2008) compare the impact of integration on the economic growth of LA and East Asia, the results of which show Asian countries have enjoyed a greater degree of openness, a stable economic environment and are more integrated with the WTN than LA.

From the present perspective of these studies, some research projects concerned with trade policies, integration and international trade in LA stand out, such as that by Márquez et al. (2015), which evaluated the effects of different economic integration levels on international trade and the export basket in LA in the periods from 1962 to 1989 and from 1990 to 2009. The research was conducted with the 11 member countries of ALADI and 161 business partners. The results show an increase in exports of cereals, vegetables and fruits, and non-ferrous metals after signing the FTAs. Among the positive effects were the growth in exports and a considerable increase in exports of new products to new markets during the wave of open regionalism, which became more extensive after 2001.

Rajagopal (2007) reviews the approach to trade policy and the evolution of the ideas that integrate economic and structural reforms in LA and Asia. The author states that the most common pattern in economic policies in LA has been radical liberalization and implementation of prudent rules to moderate the initial liberalization. This author notes that economic policies can be evaluated by examining their corresponding measures and implications, however, all economic progress may not be interpreted as a result of the policies. On the other hand, Rodríguez and De Lombaerde (2017) showed that in terms of trade policy, economic and institutional factors influence economic integration. In this way, several authors have used macroeconomic variables (Basnet and Sharma, 2013), like trade flow and export basket, as variables (Dingemans and Ross, 2012) to study the impact of economic policies.

3. Methodology

This study used a mixed approach. The qualitative approach was used in the documentary analysis of the government plans of Peru, Chile and Colombia from 1980 to 2018, which identified the following categories: export development, integration agreements and institutional development (Guerrero, 1995). Then, a descriptive quantitative approach was adopted to evaluate the effects of trade policy based on the following variables: trade balance, exports, GDP (identified by ECLAC and the World Bank) and products exported (according to the Uniform Classification for International Trade (CUCI per its acronym in Spanish)). The information was collected according to the data on trade agreements in the Information System on Foreign Trade (SICE per its acronym in Spanish). Moreover, to analyze the effect of exports on the GDP, the VAR models developed by Sims (1980) were used to solve the variables’ endogeneity issue, as it can be seen how changes on one variable affect the other variables. The model is expressed as the following system of equations:

The result is a simultaneous equations model characterized by endogenous variables. In matrix form, the VAR model is expressed as:

The equation obtained by the GDP logarithm and the logarithm of export is presented. Given the above results, Yt is a 2 × 1 vector of endogenous variables and organized by the order of exogenous variables:

4. Results

4.1. Analysis of the Evolution of Colombia’s Trade Policy

The economic opening policy in Colombia dates back to the year 1959, the year the Vallejo Plan was issued, which sought to create import exemptions for raw materials. This plan saw a small leap forward in the second half of the twentieth century, thanks to programs such as President Lleras’s non-traditional exports, or the incorporation of INCOMEX, which would later become PROEXPO. Subsequently, the governments of Pastrana and López, saw an export strategy focused on diversification, which paved the way for the Turbay and Betancourt governments to take the first steps towards economic liberalization, facilitating the import of inputs. Finally, the Barco government consolidated export zones in addition to reducing tariffs on the basis of sectors (Planeación, 1990).

By the early 1990s, the liberalization of the Colombian economy obtains one of its greatest boosts thanks to President Gaviria, who developed a program to modernize the economy, along with tariff reductions and reforms to restrictions of entry, thus generating a more favorable environment to attract foreign capital. It is also worth mentioning the promotion and creation of institutions such as the Ministry of Foreign Trade, Fiducoldex, and Proexpo, which supported the liberalization process.

The path of economic opening served the subsequent Samper government in the development of international negotiations such as the G3 (Mexico, Venezuela and, Colombia), and the treaties with Chile and the Caribbean community. In this way, the Pastrana government continued to consolidate treaties such as the FTTA, the partial-scope agreement with Cuba and the extension of the Andean Tariff Preferences and Drug Eradication Act (ATPDEA). However, the country saw an exponential increase in violence during this period, which led to the loss of international confidence, and caused the following government, led by President Uribe, to focus on Democratic Security, which sought to restore the confidence of international markets and foreign investors. It should be noted that the trade policy of this government focused on competitiveness issues, and the mining and energy sectors were promoted. Furthermore, it consolidated international treaties and created the Ministry of Commerce and the Ministry of Tourism.

President Santos received a country that had regained the confidence international markets, and trade policy expanded to the negotiation and implementation of treaties with the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) and Canada in 2011, and the European Union in 2013. In 2012, the FTA with the United States entered into force. In 2011, the Pacific Alliance was created as a political and economic regional integration initiative. The government founded the Single Window of Foreign Trade (VUCE per its acronym in Spanish) and the Customs MUISCA, as part of a process optimization (Planeación, 2010). In addition to that, the government also committed to improving the country’s infrastructure, through 4G projects known as the fourth generation. By Santos’s second term, customs operations had been enabled in Specialized Logistics Infrastructures (Planeación, 2018). To address adverse situations regarding falling international oil prices, the government had exploration and exploitation contracts adjusted, and the Free Trade Agreement with Korea and the FTA with Costa Rica entered into force in 2016.

In short, between 1980 and 2018, the most important events in Colombia’s trade policy were the modernization of the economy, the opening of trade, the creation of institutions oriented to foreign trade, and the abundance of free trade agreements. Since 1990 to date, Colombia has 16 trade agreements in force with 62 countries. The types of policies implemented by different governments over the years have impacted international trade, which the dynamics of exports have reflected.

4.1.1. Export Dynamics of Colombia.

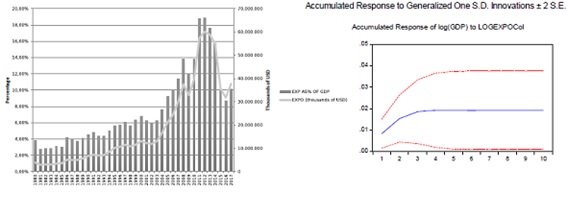

In Colombia, exports grew significantly from 1980 to 2012 (Figure 1a), and their share in the GDP increased above 18% in 2012. From 2000 to 2008, they increased from USD 13.114.734 (thousands of USD) to USD 37.625.408 (thousands of USD), and in 2012 increased to USD 60.125.164 (thousands of USD) but started to decrease in 2013 due to low prices in energy and mining products, and the strongest drop was felt in 2015 (35.690.776 thousand of USD). Figure 1b shows the cumulative response of the GDP to 2 standard deviations for exports with a 95% confidence interval. In addition to the cumulative response of the GDP to exports, it is evident that increased exports in Colombia have generated a positive and significant impact on the GDP for more than 10 periods1. According to Candelo (2018), Colombia’s GDP is dependent on oil prices, which is its main export product; therefore, there is a significant relationship between GDP and exports.

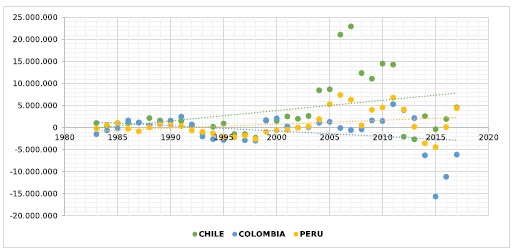

Colombia has belonged to the CAN and the ALADI since 1980, and it joined the G3 and FTAA in 1991 and 1995, respectively. Furthermore, the country has negotiated Free trade agreements with EFTA, the Northern Triangle, the United States, Canada, Chile, the European Union, Costa Rica, Korea, Mexico, and the Pacific Alliance. However, the trade balance in Colombia has tended towards deficit since 1980, contrary to Chile and Peru’s surplus trend (Figure 2).

4.2. Peru’s Trade Policy Evolution Analysis

In 1980, the government of Fernando Belaúnde continued the privatization process that facilitated the inflow of foreign capital into mining products under the ‘Kuczynski’ Act. The government of Alan García (1985-1990) began by rejecting the International Monetary Fund as an intermediary in the face of the country’s external debt crisis, with a 10% restriction on imports. The economic situation was under control due to positive aggregate domestic demand and a surplus trade balance. The government, by its foreign exchange policy, had the dollar under control, but this did not work in 1988 when cumulative inflation reached 210%, devaluation increased to 50% (49 intis to 138 intis) and the economy went into recession.

The main feature of the Fujimori government (1990-2000) was the development of the primary export model, thereby starting the commercial opening (Dancourt, 1997). Its main objective was to promote foreign investment in the exporting extractive sector and the privatization of State-owned companies. In this period, the Complementation Agreements with Cuba and Mercosur were signed. Later on, Toledo (2001-2006) focused on promoting different sectors with competitive advantages, proposing investment in agricultural infrastructure such as fish farms. His main engine for economic growth was the mining sector.

On his part, García (2006-2011) aimed to increase competitiveness to promote the domestic industry. His proposal was intended to strengthen institutions such as Petroperú, Electroperú, ENAPU, Sedapal, and to create entities focused on the exporting process, namely, PROMPERU and PROMPEX. During this period, the Peru-Chile Free Trade Agreement was signed, together with the FTA with Canada and Singapore, the FTA with China in 2010 and the FTA with EFTA and South Korea. Garcia was among the promoters of the Pacific Alliance as a deep-integration area.

On the other hand, Humala (2011-2016) proposed ending the neoliberal model, which was regarded as denationalizing and exclusionary. However, the government worked on the implementation of Free Trade Agreements, specifically, it proposed to strengthen regional integration with CAN and MERCOSUR. In 2012, the FTA with Mexico, Panama and the Peruvian Economic Partnership Agreement and the Pacific Alliance entered into force, while the FTA with Costa Rica, the European Union and the Partial-Scope Agreement with Venezuela did so in 2013. Later on, the Kuczynski government’s trade policy sought to create a framework for the positive flow of both imports and exports. In 2016, a Trans-Pacific Strategic Economic Partnership Agreement was signed, the FTA with Honduras entered into force in 2017, and an FTA was signed with Australia in 2018. The government created the Single Window for Foreign Trade (VUCE per its acronym in Spanish), to improve the processing of companies’ formalities. The functions of MINCETUR, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and PROMPERU were also redefined. The exportable basket of Peru was diversified to sectors such as tourism and the agroindustry.

According to the WTO (2013), the economic performance for Peru has been remarkable because it achieved macroeconomic stability and continued structural reforms, privatization and financial deregulation, which facilitated and promoted foreign investment. Peru decided to negotiate trade agreements with the countries to which it sold the most, which nowadays account for 21 agreements in force, 5 about to enter into force and 5 under negotiation.

4.2.1. Export Dynamics of Peru.

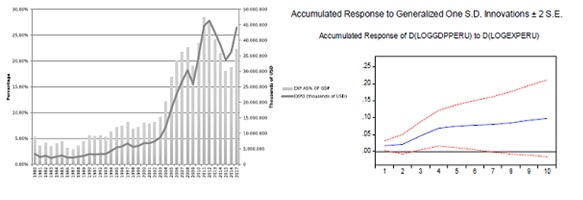

The economy of Peru was a critical condition in 1980, and it was characterized by stagnation in exports as a result of strong para-tariff measures that increased the cost of goods. However, between 2002 and 2013, Peru was one of the Latin American countries with the highest GDP growth rate at 6.1% annually (World Bank, 2019) and a surplus trade balance, which represents increased exports that accounted for 28% of the GDP in 2011 (Figure 3). Conversely, figure 3b shows the cumulative response of the GDP to 2 standard deviations concerning exports with a 95% confidence interval. For the VAR model, Peru’s exports affect the GDP in periods 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6, an effect of exports on the GDP that began to diminish as of the last period.

Peru negotiated free trade agreements with the European Union, Japan, Costa Rica, Panama, Mexico, South Korea, China, the European Free Trade Association (EFTA), Singapore, Canada, Chile, the United States, MERCOSUR, and Thailand. In 2016, it joined the Pacific Alliance, and it signed a free trade agreement with Honduras in 2017.

4.3. Chile’s trade policy evolution analysis

The military government of Augusto Pinochet is the first government in the region that implemented a neoliberal economic approach. Its main feature was a free market economy, including the abolition of widespread price controls. In 1974, the Institute for the Promotion of Exports was responsible for promoting exports of goods and services in the country and for helping stimulate foreign investment and tourism in Chile. Faced with the process to open up trade, one of the main measures the government enacted was a reduction of tariffs by 10%, which were up to 44% by 1975 (Delano and Traslaviña, 1989). Pinochet left the following traces in commercial matters: elimination of anti-export bias, greater and diversified exports in terms volume, products, and markets, a competitive exchange rate, structural reforms, deregulation and privatization, the economic openness, the arrival of foreign capital was facilitated by encouraging foreign investment, and free trade agreements signed with Latin American countries.

In 1990, Patricio Aylwyn’s government priorities were to consolidate democracy and face social debt after 17 years of military rule (Olavarría, Navarrete, and Figueroa, 2011). This government had to deal with years of complex international relationships but was able to normalize diplomatic relationships by concluding trade agreements with Mexico, entering into the Rio Group and the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation bloc. In 1994, Eduardo Frei’s main axes were productive, social and quality of life infrastructure, and integration, highlighting the creation of the port of Punta Arenas (Partido Demócrata Cristiano, 2004). Then Ricardo Lagos was challenged with improving conditions in terms of competitiveness for companies, it focused on the internationalization of the Chilean economy, open regionalism with Mercosur and promoted the protection of domestic companies.

The Bachelet government focused on trade agreements, especially with LA, and increased the volume of exports to the region, as well as on strengthening tourism, and economic ties with potential partners to develop energy, mining, and infrastructure. For this reason, the Government expressed the country’s commitment to the South American Community of Nations and the South American Regional Integration Initiative. After Bachelet, the government of Piñera was recognized for its great capacity to solve economic problems (Navia and Rivera, 2019), whose trade policy revolved around two fundamental axes: the development of infrastructure, especially in the mining industry, and promotion of the trade agreements negotiated. This government proposed an increase in R&D, which rose from 0.7% of GDP to 1.2%, and also outlined multilateral actions to promote an integrated energy and infrastructure market in the Southern Cone, aside from furthering agreements with the European Union and the Association of Southeast Asian Countries (ASEAN).

Bachelet’s trade policy between 2014 and 2018 set out to support domestic companies, for which adjustments were made to the tax policy to maintain a competitive exchange rate and to expand the Export Promotion Fund in order to develop agriculture and the livestock sector. The government focused on strengthening its participation in the existing integration mechanisms in LA such as UNASUR and the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC) concerned itself with negotiating the Transpacific Partnership (TPP) and proposed repealing the DL 600, Foreign Investment Statute, and replacing it with new investment projects.

In short, the legacy of Chile’s trade policy from this period is an economy fully integrated into the world, a wide network of trade agreements, and reduced tariffs. Though strong increases in shipments of raw materials led the expansion process at first, the emergence of new industrial products, with greater added value, was the main strategy, especially those from the agro-industry as the evolution of the country’s export structure has demonstrated.

4.3.1. Export Dynamics of Chile.

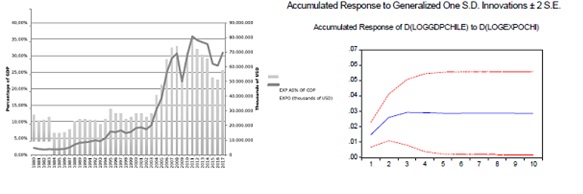

Chile’s exports increased significantly compared to their share of the GDP, escalating from 7.90% in 1980 to 34.83% in 2011 (Figure 4). From 2003 to 2007, dynamism in exports grew remarkably, and by 2011, despite the decline in copper prices (CEPAL, 2012), foreign sales had risen considerably; however, prices dropped in 2014 due to low external demand for copper. Figure 4b shows the cumulative response of GDP to exports, which illustrates that increased exports in Chile have brought on a positive and significant impact on the GDP for over 10 periods, as was the case of Colombia. Chile grew its access to international markets through the signing of trade and economic complementation agreements (Ffrench, 2002). Chile’s trade balance, after intensifying integration, has produced surplus results, which reflect high levels of competitiveness and productivity have earned it its place as the most competitive country in LA.

In summary, Colombia, Peru, and Chile have adopted very similar trade policies oriented towards open integration, all put forward within the framework of the Washington Consensus and strongly oriented towards trading the United States, Europe, and Asia. Despite the three economies having adopted similar guidelines in terms of economic policy, the actual economic results after enacting the trade policies have not been similar. It should be noted that the structure of exports has changed throughout the period studied in the three countries, some of which are shown below.

4.4. Dynamics in the structure of exports of Colombia, Chile, and Peru

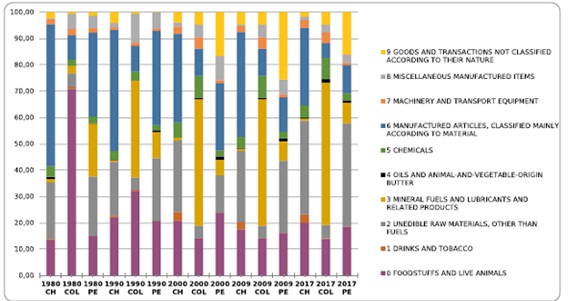

The products that, according to the Standard International Trade Classification (SITC), represented a significant share of exports over the past 37 years in Colombia, Peru and Chile are described in Figure 5. The impact of minerals and hydrocarbons on Latin American economies is admirable, for they managed to enter the trade balance as traditional products.

In Chile, for example, before 1980, 85% of exports came from mining, mainly copper, while only 2.5% came from agricultural and forestry products and fisheries. After 1980, the Chilean economy diversified and concentrated on three strategic sectors: food products and live animals, raw non-edible materials and manufactured goods. In recent years, these sectors have accounted for more than 70% of the total export basket. Fish and fish preparations grew their share in 2017, which accounted for 8.01% of total exports. The most outstanding products in this category are salmon, frozen trout and fish fillets. Fruits and legumes were above 9% of the total exports in 2017; fresh grapes were the most representative category. Similarly, inedible raw materials, metalliferous minerals, and metal scrap more-than-doubled their share: from 10.68% in 1980 to 28.54% in 2017.

Copper promoted Chile’s economic advancement, a boom that was driven by rapid growth in global demand thanks to the electric power industry, the expansion of the construction sector and technological innovation in the United States. Even though copper has remained stable over the years, in 2003 it was at its highest point: 1USD per pound; in 2008, it climbed above 4USD per pound. One of the most important milestones for the marketing of ore abroad was the strengthening of relations with China and the prices in 2018 (Santa Cruz, 2018).

The analysis for Colombia (Figure 5) shows that only two out of ten sectors have changed considerably in the last 37 years. In 1980, the group of foodstuffs and live animals accounted for 70% of total exports, including coffee, but between 1997 and 1998, the fuel and lubricants group gained momentum and came to be on par with the food and live animals sector. From this period on, hydrocarbons gained greater strength. In Brazil (1970), due to the winter, many coffee crops were lost, a situation that favored Colombian exports because domestic and external prices of the grain increased between 1975 and 1977. Despite the opening of markets, coffee production was regulated by multiple agreements, including the International Coffee Agreement (AIC). In 1980, coffee exports accounted for more than 50% of total exports, but in 1990, after the end of the AIC, it fell markedly to 20% of the total exports.

On the other hand, oil exploitation in Colombia began in 1905, and the Ministry of Mines and Energy was created in 1940. By 1961, Ecopetrol had begun operating the Barrancabermeja Refinery and would run the Cartagena Refinery later on. Production grew from 1980 to 1985, and Colombia went from being an importer to an exporter of oil, and oil and petroleum products accounted for more than 25% of total exports by 1987. Currently, their share of the GDP surpassed 30% (Reina, 2015). Even though oil reached the record price of USD 124 in 2008, the following year saw it close at USD 70, for 2009 was the year oil prices fell sharply up to USD 40, a crisis that intensified further between 2014 and 2016.

Gold, bananas, sugar, and flowers have also had a significant share of Colombian exports, currently accounting for 3.8%, 2%, 1% and, 3%, respectively. Regarding the manufacturing sector, the share of the food and beverage subsectors accounts for approximately 10% of exports and clothing and clothing items kept up their participation at 2.01% (2017). The production of chemicals and substances has continued in recent years, currently representing 6.2%.

In 1980, Peru’s manufactured goods accounted for over 30% of the total, and by 2017, they accounted for 11%. Mineral fuels and lubricants accounted for 20% in 1980 but did not even make it to 10% by the last year of the analysis. Meanwhile, the foodstuff sector has kept a constant dynamic. For their part, inedible raw materials increased their share significantly, as they represented 40% of the total in 2017. The traditional products of the Peruvian export basket come from mining (gold, copper and, zinc) and fishing (fishmeal). Finally, textiles and agricultural products stand out among non-traditional products (Mendoza, 2013).

In 1990, the average value of exports of agricultural products grew 11.3%, chemicals 10.4%, non-metallic minerals 11.0% and mechanical metals 9.6% (Araoz, 2005). In 1980, metals and their waste accounted for more than 18% of total exports; aluminum and chromium were the main exporting products, and by 2017, this group had concentrated more than 37% of total exports. Oil and oil-related products passed from a 20% stake in 1980 to only 6.06% in 2017, and petroleum products were the main component. The same behavior was observed in non-ferrous metals: in 1980, they held more than 25% of exports and had dropped to 8% by 2017. Exports picked up in 2017 thanks to an increased sale of traditional products, including fishmeal, copper, gold, zinc and petroleum products.

In short, all three countries have designed very similar integrationist trade institutions and policies, but the results show that Chile and Peru have diversified further and have not suffered such drastic changes as Colombia has, which went from depending on coffee to depending on oil. Colombia is at a disadvantage because it has failed to enact an export strategy or a trade agreement with China, which is evidenced by the lower share of its exports (9.7%) to that country, compared to imports (20.6%). Due to its rapid industrialization, China consumes between one- fifth and one-third of the world trade in aluminum, iron, copper, and zinc, a great opportunity for Chile and Peru (Shadlen, 2008). A proof of the above is that in 2017, Chile’s balance in favor balance with regards to China was 4.020 million dollars, and Peru’s was 3.273 million dollars. China accounts for 13.7% of Peru’s exports in two products: fishmeal and copper. Peru is the ninth supplier of fruits to China and Chile is the second.

5. Conclusion

One of the trade policy-related challenges faced by most developing countries is the diversification of their export basket. According to the results obtained in the VAR model, the GDP in Colombia depends significantly on exports and oil prices, and while the GDP of Chile is positively and directly related to exports and copper prices well, the latter’s exports are more diversified. On the contrary, in Peru, the effect of exports on the GDP has diminished in recent periods. One hypothesis for this result could be that its main exporting products, such as fishmeal, do not have fluctuating prices as do oil and copper.

Since the late 1960s, Peru, Colombia and, Chile, have been explicitly interested in diversifying their exportable supply, for which they adopted two strategies: one aimed at import substitution, backed by policy to promote exports and expand markets through regional trade agreements, while the second one consists in opening up trade and is backed by a type of open integration. The first strategy did not yield the desired results, so all three countries decided to open up their economies to world markets. Regarding the institutions created for foreign trade, the types of open integration adopted were similar in these countries, although Colombia signed fewer trade agreements. Similarly, the development of exports has played an important role in the economic growth of these countries, which is consistent with the result of Márquez et al. (2015). Nevertheless, the results, in terms of export diversification and trade balance, are very different. According to the results, Colombia has not diversified its exports and continues to be an exporter of raw materials, which makes it extraordinarily vulnerable to fluctuations in the international market and becomes reflected in a deficit trade balance.

Consequently, free-market trade policies, integration have not achieved the expected results in Colombia in terms of diversification. One possible cause for this is its economy’s delayed internationalization. Chile and Peru, for instance, signed an FTA with the United States before Colombia, and the results have been positive in terms of economic growth. However, many years have passed in Colombian since this FTA and the results have not been significant. Peru and Chile concluded an FTA with China and the results of the trade balance have shown in the form of surpluses, but Colombia has yet to sign an FTA with China, for it is a more attractive market as stated by Genna (2010) .

It would be interesting for future research to expand the analysis into the impacts of international trade in other countries from LA with similar trade politics. Furthermore, it would be interesting to analyze how integration helps eliminate barriers and enables coordination and unification of trade processes in LA. The author of this paper together with other researchers recommend continuing to investigate what has happened in other countries regarding their economic integration and internationalization processes, as well as the efficiency of their public policies, which are a reference for LA in its regional integration process, like that of the European Union, the Association of Nations from Southeast Asia, among others.