1. Introduction

Diversify, or don’t diversify? Take risks, or play it safe? Expand internationally, or not? These are questions that a company must ask itself if it must make an impact in the market. Establishing a strategy entails having competitive advantages, healthy finances, and capacities for research and development-plus an evaluation of possible risks. Business diversification is present in most industries and organizations, regardless of size.

During recent years, globalization has become even more rapid and sought-after in markets. Shareholders have responded by modifying their business portfolios, opting for diversification at the international level because of openness of trade and worldwide tendencies toward competition. Some interesting data has been generated regarding the proportion of firms in emerging economies (such as Mexico’s) that are actively diversifying, or that operate outside their countries of origin, or both. The data reveal the typical benefits of those practices: reduced risk exploitation of synergies between related businesses, and operating in a new line of business, or in markets outside one’s own country.

However, certain criteria exist. Therefore, a company that contemplates diversifying must analyse carefully before taking that step. To that end, it is necessary to know how diversification strategies might benefit companies that exist at present in Mexico, and whether those strategies bring higher earnings. For example, in 2019 2% of Mexico’s international exports went to its two principal trading partners: the US and Canada (Organización Mundial del Comercio, 2021). A greater degree of diversification toward foreign markets would be desirable, and would bring a range of benefits.

Business diversification is a subject that has been investigated extensively since the end of the 1950s (Baumol, 1959; Rumelt, 1974; Bettis, 1981; Christensen and Montgomery, 1981; Rumelt, 1982; Wernerfelt and Montgomery, 1988; Grant, Jammine, and Thomas, 1988; Penrose, 1995; Palich, Cardinal, and Miller, 2000; Ramírez and Espitia, 2002; Xiao and Greenwood , 2004; Gary, 2005; Miller, 2006; Pehrsson, 2006; Chang and Wang, 2007; Elsas, Hackethal, and Holzhäuser, 2010; Purkayastha, Manolova, and Edelman, 2012; Galván, Pindado, and de la Torre, 2014; Galván, García-Fernández, and Serna, 2017). However, the subject has not been exhausted: firms are constantly venturing into new lines of products, while at the same time applying new strategies to reduce risks, increase benefits and efficiency, and reach new markets.

As its direction for growth, a company may consider either expanding its economic activity, or diversifying. The latter alternative is the focus of this article. Diversification is the act in which a business either expands its product line, or enters new markets in order to obtain benefits or create value in the market (Galván et al., 2014).

Some authors consider that businesses with activities in other geographical areas obtain profits that outweigh the costs that are related to the responsibility of operating in foreign countries (Morck and Yeung, 1991; Bodnar, Tang, and Weintrop, 1999). Other authors have found that the when a business expands its foreign operations, it may be faced with more challenges-from institutional frameworks, for example-that are related to the obligations of being in other countries. These challenges can bring about the destruction of the business’s value (Hymer, 1976).

Diversification is understood as the heterogeneity of products that are offered in a wide range of markets (Gort, 1962). Meanwhile, for Booz, Allen, and Hamilton (1985), diversification is the extension of a business’s base in order to reduce the business’s global risk. For the purposes of the present work, a “diversified business” is one that expands its line of products, or enters new markets in order to obtain profits or create value in the market.

The objectives of this work are to (1) understand the diversification decisions of Mexican businesses; (2) determine the proportions of Mexican businesses that decide to operate nationally versus internationally; and (3) calculate the relative proportions of sales by companies that diversify (but operate only in Mexico), versus sales by companies that have international operations, versus companies that diversity as well as operating internationally. The principal research question is, “Are Mexican companies that diversify their products more inclined to internationalize their companies’ activities?

2. Theoretical Framework

According to Ramanujam and Varadajan (1989), diversification is the incorporation of new activities by developing business processes internally or acquiring them in the market, thereby generating modifications in the business’s administrative and organizational structures. Suárez (1993) points out that business diversification consists of the decisions that produce or expand a business’s scope of activities. For Berry (1974), diversification is associated with the increase in the number of sectors in which businesses operate. In contrast, Kamien and Schwartz (1975) consider this strategy as the degree to which businesses in a particular sector produce goods that are classified as belonging to another. Meanwhile, Hassid (1977) refers to diversification in the sense of inter-industrial movements.

Empirical investigations show that operating in multiple business segments has costs as well as benefits. The benefits of diversifying include the creation of internal capital markets that allow a more efficient allocation of resources (Stein, 1997). Useful synergies may result from the sharing of resources and capacities among a business’s distinct activities (Tanriverdi and Venkatraman, 2005). Diversification may also disperse risk (Lubatkin and Chatterjee, 1994), increase a business’s borrowing capacity (Lewellen, 1971), and have fiscal advantages (Berger and Ofek 1995). Prominent costs of diversification include those associated with agency problems, as directors seek personal gain (Morck and Yeung, 1991). Inefficiencies of internal capital markets are additional costs, as are the recruiting and training of new managers (Penrose, 1995).

Internationalization of a business is a corporate strategy of growth via international geographical diversification. This strategy is reflected in changes to organizational structure and the locations of the various links in the value chain. As the company evolves, those links commit resources and capabilities to the international environment (Araya, 2009). Andersen (1993) understands the internationalization of a company as “the processes of adapting modes of exchange transaction to international markets” (p. 34). That is, internationalization is a very dynamic activity that includes the strategy of how to select an international market as well as how to enter it, and in what degree.

In the first theoretical works on this subject, economists argued that one motivation for innovative companies to diversify geographically is higher returns on their investment in production and innovation (Caves, 1982).

Like product diversification, international diversification has costs as well as benefits (Bowen and Wiersema, 2008). The benefits might be maximized by increasing the degree of international diversification, given that companies see higher yields when they increase the scales of their international operations. However, the potential benefits come at a cost, such as the costs associated with the learning curve for operating in a foreign country, and for seeking legitimacy in different environments. Barkema and Vermeulen (1998) argue that over time, these costs decrease as the company becomes familiar with foreign markets, and more experienced at operating within them.

A range of authors highlight that a company diversifies at the international level when there is a strong, positive linear relationship in their results (Kim, Hwang, and Burgers, 1993). A relationship with those characteristics might result when (for example) the company is large enough to receive or create certain advantages, such as increased monopolistic power (Hymer, 1976). Other possible advantages include obtaining favourable prices for resources; the opportunity to share costs of R&D and commercialization; and the economies of scale and of operating in large, geographically extensive markets (Porter, 1986). In contrast, the literature contains examples of a negative linear relationship, which Geringer, Tallman, and Olsen, (2000) attribute to a shortage of resources (and especially experience) during the initial phases of a company’s internationalization. According to those authors, operating in a large number of countries may prove too difficult. It should be noted, though, that some studies found no significant linear relationship, either positive or negative (Morck and Yeung, 1991; Hennart, 2007).

Companies that combine product diversification with internationalization must take into account the cultural and institutional characteristics of the places in which they are investing: knowing the local environment and adapting to it are essential for success (Bartlett and Ghoshall, 1989; Zaheer, 1995; Delios and Beamish, 1999). According to Gongming (2002), companies that have diversified must consider an appropriate level of international and product diversification. An earlier study suggests that the relationship between the two types of diversification is curvilinear (Lozano Posso, 2004): the results are positive up to a certain point, after which further expansion of these strategies brings diminishing returns.

The relationship between diversification and internationalization has been studied by various authors (Lozano Posso, 2004). These authors allege that a moderate diversification results in a larger capacity for exportation. However, a common tendency is that when a firm begins to consolidate, it takes bigger risks, either by undertaking a larger, related diversification or by diversifying in an unrelated way (Palich et al., 2000).

3. Data and methodology

In relation to the theoretical approaches mentioned in the preceding section, regarding the principal variables in diversification, the present section presents the aspects related to the design of the investigation, and describes the type of study and the principal source of information that was used.

The methodology used in this study is quantitative and descriptive. It allowed the authors to calculate the “intensity” of the variables-mainly the proportion of companies that have operations in more than one business segment, as well as outside their countries of origin. The study was based upon data for 97 Mexican companies that list their stock on the Mexican Stock Exchange. To provide a robust basis for interpretation of results, the authors obtained from that database a representative sample of observations made between 1996 and 2007.

Malhotra (1997) defines descriptive analysis as a method whose purpose is to describe something-for example, the characteristics or functions of the problem under discussion. Through the use of descriptive statistics, researchers can organize and classify quantitative indicators obtained from databases. Those indicators can then be examined in detail to detect the tendencies of each, as well as the relationships among them. One of the tasks of descriptive investigation is to specify the properties, characteristics, and traits of the problem that will be analysed. Descriptive studies may analyse a diversity of variables, but differ from other methods in that descriptive studies need only one variable (Borg and Gall 1989).

To answer the present study’s research question, the authors collected and analysed data. The analyses included numerical measures, counts, and (frequently) statistics to establish exactly the patterns of behaviour in a population (Hernández, Fernández-Collado, and Baptista, 2006).

The Worldscope Global database is the principal source of information on the finances and profiles of public companies whose headquarters are outside the US. Worldscope also has complete coverage of US companies that are affiliated with the Securities and Exchange Commission, except for investments of closed-end investment companies. From primary sources and news clippings, Worldscope’s analysts extract data into global templates that are specific to industry groups. The template take the variety of accounting conventions into consideration, and are designed to facilitate comparisons among business and industries within and outside of national boundaries. Worldscope offers professional analysts and portfolio managers the most complete data, précis, and opportunities for publicly listed companies worldwide. Worldscope’s objective is to improve the intercomparability of financial data of companies from different countries and industries, and over a period of time.

The variables presented in Worldscope help to capture and systematize the knowledge that a company has acquired through its activities and international markets. In this way, every phase that is mentioned influences more-efficient decision-making in the international environment.

The data for Mexican companies were taken from the databases of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). The variables (Table 1) used by the authors are fundamental for understanding each company’s foreign activities, and how it manages its product portfolio in order to be more profitable.

Table 1 Definitions of Variables

| Variable | Measure |

|---|---|

| Diversified companies | Diversified=0, Not diversified=1 |

| Internationally diversified companies | Internationally diversified =0 Not diversified internationally=1 |

| International sales | Foreign sales |

| Product 1 | Sales in the segment of product 1 |

| Product 2 | Sales in the segment of product 2 |

| Product 3 | Sales in the segment of product 3 |

| Product 4 | Sales in the segment of product 4 |

| Product 5 | Sales in the segment of product 5 |

Source: Prepared by authors with data from Datastream Worldscope.

The information about the variables used in this investigation was obtained from the Worldscope datastream database (Table 1). The variables were: sales, net income, and net assets. They were chosen in order to understand fully which companies are diversified; which have foreign sales; and whether there is any relation among their products.

An analysis of these variables indicates the companies’ lines of business, and whether the companies’ incomes derive from a single, principal product or from many different ones. The variables of diversified companies and internationally diversified companies show which ones are currently diversified, and which are diversified at the international level. To obtain these variables for a given company, there must be a record of each company’s products, along with the values of each variable for Product Segment 1, Product Segment 2, and so on. If a business has sales for Product Segment 2 (or others in addition to Product Segment 1) then the variable “Diversified Businesses” generates the value zero. On the other hand, that variable generates the value “1” if the business has sales only for Product Segment 1. In addition, it is necessary to know whether there is some relationship among the products of the diversified companies. That information is provided by the variables “Diversification of Product 1”, “Diversification of Product 2”, etc.

4. Results

Table 2 lists and describes the 97 Mexican companies whose activities during 1996-2007 were followed in this study. Each company is listed on the Mexican Stock Exchange.

Table 2 Description of the observed companies

| Company | Description of the company’s business segment(s) |

|---|---|

| Acer Computec Latino America SA DE CV | Portable devices (Technology) |

| America Telecom SA DE CV | Telecommunications |

| Accel Sab de CV | Logistics |

| Alfa Sab de CV | Production of petrochemicals, and automotive components, among others |

| Alsea Sab de CV | Representation and operation of restaurants |

| America Movil Sab de CV | Communications |

| Axtel Sab de CV | Information technologies and communication |

| Bufete | Customs services |

| CMR Sab de CV | Restaurant corporation |

| Consorcio G Grupo Dina, SA DE CV | Real estate, logistics, and foods, among others |

| Controladora De Farmacias | Pharmaceuticals |

| Carso Global Telcom Sab de CV | Telecommunications |

| Carso Infraestructura y Construcción | Industrial, commercial, and consumer consortium |

| Cemex Sab de CV | Construction |

| Coca-Cola Femsa | Bottling and beverages |

| Compañía Industrial de Parras SA de CV | Textiles |

| Controladora Comercial Mexicana | Supermarket chain |

| Coppel SA de CV | Commercial and financial services |

| Corporación Durango Sab de CV | Paper and cardboard packing |

| Corporación Interamericana De Entretenimiento | Entertainment |

| Corporación Moctezuma Sab de CV | Construction |

| Corporativo Fragua Sab de CV | Pharmaceuticals |

| Cydsa Sab de CV | Specialty chemicals; steam and power cogeneration |

| Desarrolladora Homex | Housing developer |

| ECE SA De CV | Job bank for construction and real estate |

| Embotelladoras Argos SA | Bottler |

| Embotelladores del Valle de Anahuac | Bottler |

| Edoardos Martin Sab de CV | Manufacturing and sales of fabrics |

| El Puerto de Liverpool Sab de CV | Department stores |

| Embotelladoras Arca | Bottler |

| Empresas Cablevision | Telecommunications |

| Empresas ICA Sab De CV | Construction of infrastructure |

| Farmacias Benavides Sab | Pharmaceuticals |

| Fomento Económico mexicano Sab De CV | Beverages, restaurants, and commercial sector |

| Grupo IMSA Sab de CV | Foods, beverages, cosmetics, among others |

| Grupo Sanborn SA de CV | Cafeterias and department stores |

| Grupo Sanborns SA de CV | Cafeterias and department stores |

| Grupo Situr SA de CV | Hotels |

| Grupo Videovisa SA de CV | Entertainment |

| Grupo Covarra, SA de CV | Textiles |

| Gruma Sab de CV | Foods |

| Grupo Sab de CV | Hotels, real estate, construction, etc. |

| Grupo Aeroportuario Sureste Sab De CV | Airports |

| Grupo Bafar SA de CV | Foods (meats) |

| Grupo Bimbo Sab de CV | Baking |

| Grupo Carso Sab de CV | Commercial, communicational, industrial |

| Grupo Casa Saba Sab de CV | Pharmaceuticals, health, and beauty |

| Grupo Cementos de Chihuahua | Construction |

| Grupo Continental Sab de CV | Production, distribution, and sales of beverages |

| Grupo Corvi SA de CV | Groceries |

| Grupo Elektra SA de CV | Specialist shops, financial services |

| Grupo Gigante Sab de CV | Self-service, cafeterias, specialist shops. |

| Grupo Herdez Sab de CV | Self-service, cafeterias, specialist shops |

| Grupo Industrial Maseca Sab de CV | Production and sale of corn flour |

| Grupo Industrial Saltillo Sab | Construction, home and auto |

| Grupo Iusacell SA de CV | Telephony and telecommunications |

| Grupo Kuo Sab de CV | Consumer sales, chemicals, and automotive |

| Grupo Lamosa Sab de CV | Flooring and tile |

| Grupo Martí Sab de CV | Sports equipment |

| Grupo Mexico Sab de CV | Production of copper |

| Grupo Minsa Sab de CV | Production of corn flour |

| Grupo Modelo Sab de CV | Brewer |

| Grupo Movil Access SA de CV | Mobile telecommunications |

| Grupo Palacio de Hierro | Department stores |

| Grupo Posadas SA de CV | Hotels |

| Grupo Qumma SA de CV | Holding company |

| Grupo Radio Centro Sab de CV | Radio station |

| Grupo Simec Sab de CV | Steel fabricator |

| Grupo TMM SA de CV | Maritime transportation |

| Grupo Televisa | Communications media |

| Holcim Apasco SA de CV | Cement and construction |

| Hylsamex, SA de CV | Fabrication of steel, among others |

| Hilasal Mexicana Sab de CV | Textiles, dedicated to the sale and printing of towels |

| Industrias Bachoco Sab de CV | Production, processing, and commercialization of eggs and chickens |

| Industrias Peñoles Sab de CV | Mining |

| Internacional de cerámica SA de CV | Flooring, tile, and related products |

| Jugos Del Valle | Beverages |

| Kimberly Clark de México | Production and sale of diverse products |

| Maizoro, SA de CV | Cereals |

| Medica Sur SA de CV | Hospitals |

| Mexichem Sab de CV | Group of chemical and petrochemical companies |

| Panamerican Beverages INC | Beverages (FEMSA) |

| Pepsi-Gemex SA DE CV | Production and sale of beverages |

| Promotora Ambiential Sab | Garbage collection, recycling, etc. |

| Promotora y Operadora de infraestructura | Construction and infrastructure |

| Sistema Axis SA de CV | Fabrication of equipment for the production of petroleum distillates and petrochemicals |

| Sare Holding Sab de CV | Development, advertising, and sales of homes |

| Savia SA de CV | Seeds for fruits and vegetables |

| Tamsa-Tubos De Acero De Mexico SA | Steel tubing |

| Transportacion Maritima Mexicana SA de CV | Maritime transport |

| Tv Azteca SA de CV | Communications media |

| Teléfonos de México Sab de CV | Telecommunications |

| Unefon SA de CV | Telecommunications y telephony |

| Universidad Cnci SA | Education |

| Urbi Desarrollos Urbanos SA | Housing development |

| Vitro Sab de CV | Fabrication of glass |

| Wal-Mart de Mexico | Commercial sector |

Source: Prepared by authors with data from Datastream Worldscope.

An examination of Table 2 shows that according to the present study, the sectors of food, telecommunications, and beverages predominate. This information is relevant to identifying which businesses are most inclined to have international activities, and to diversify.

Although the companies that are the object of this study are exclusively Mexican, the database does include information on other companies, including diversified and non-diversified ones. However, this investigation focuses principally upon companies that both diversify and have international sales.

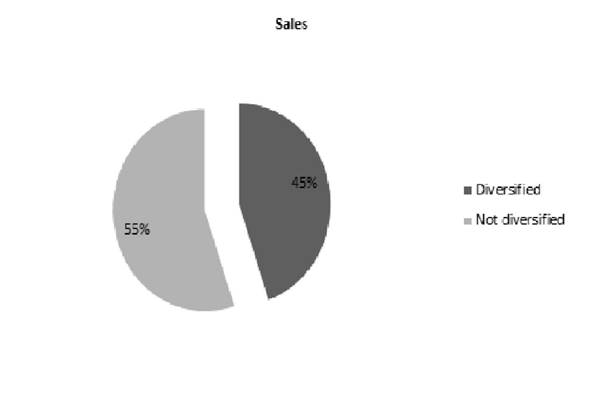

The authors studied the 1996-2007 sales of the above-mentioned companies, making a total of 511 observations. Fifty-five percent (282) of the companies were not diversified, but 45% (229) were (Graph 1). Thus, according to the data in the database, a large proportion of the companies did choose to diversify their product lines. Although the majority did not, this datum is nevertheless relevant because it shows that companies on the Mexican Stock Exchange do distribute their risk among different business units in order to obtain the benefits that accrue from that strategy. These results find support in Castañeda (1988), which affirms that the essential characteristics of companies in Mexico are a low degree of diversification, coupled with a high degree of integration. As those authors explain, “this phenomenon has been presented in terms of the benefits that accrue from specialization. In this context, the strategies of diversification seek to support growth and the profitability of the companies’ principal lines of business. Thus, the present scant diversification and integration reflect a certain aversion toward risk on the part of the companies’ management.”

Reasons exist for the large number (i.e., the above-mentioned 55%) of observations for category of companies that stick to a single business segment, rather than diversifying. One reason is the cost of carrying out the strategy of diversification. Another is the company’s attitude toward the decision to undertake a diversification process. A further reason is that economies of scale cannot be exploited easily by the Mexican industries.

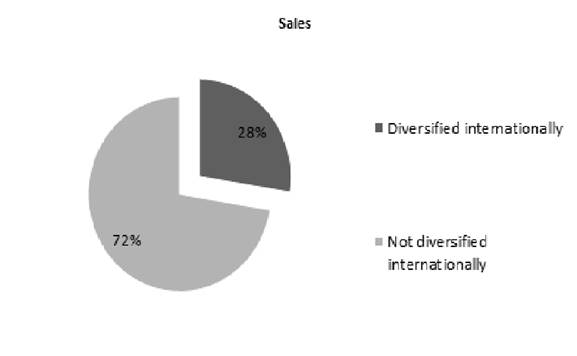

The results (Graph 2) for Mexican companies that have foreign sales show that 72% (370 companies) of the 511 observations are not diversified internationally, as opposed to only 28% (141) that are. These data provide evidence for the existence of Mexican firms that do operate business units in foreign economies. The explanation may be that a company that invests in different countries has a better chance of economic success. It is very likely that the income of a company that sells only within the national market will be strongly correlated with the national economy. In contrast, a company that operates in different countries will not necessarily be affected when one of those countries has economic problems.

5. Conclusions

The findings of the present investigation are important contributions to the study of diversification and internationalization in the context of Mexican companies. It is important to note that at present, these companies opt to use the strategy of product diversification to obtain greater benefits, such as maximum exploitation of synergies, greater control of economies of scale, and significant reduction of risks. On the other hand, diversification means having to face higher costs than might that were expected. For that reason, a large proportion of companies remain confident that their best option is to operate within a single segment.

When deciding upon their business strategies, companies take investors’ goals into consideration. Therefore, it has been thought that companies in emerging economies, like Mexico’s, will to a great extent opt for minimizing risks. Nevertheless, this study shows that a large proportion of Mexican companies accept the risks that are associated with seeking profits by operating in multiple business segments while simultaneously internationalizing their operations.

During recent years, the opportunities and risks presented by free trade and global economic development have caused an exponential growth in companies’ options for increasing their profits by diversifying and integrating their products, and by offering them in international markets. Therefore, many companies decide to venture into foreign markets that offer better opportunities for such things as growth, development, knowledge, experience, and innovation-all of which improve business performance.

It can be argued that risk-avoidance is one of the principal motivations of Mexican companies that choose to diversify. By doing so, those companies distribute their capital among different businesses or business segments. An additional motivation for a company to diversify is the possibility of generating synergies among its various product lines. Finally, as noted earlier, participation in international markets allows companies to reduce the riskiness of business decisions by spreading out the impact of downturns in particular markets.

As was shown by the sample of companies examined in this study, a considerable proportion of Mexican companies do indeed seek to increase their profits by venturing into new markets or diversifying internationally, even though most Mexican companies stick to a single business segment, and sell only at the national level.

In line with the proposed objectives of this study, it is argued that diversification can improve a company’s business results. Of course the improvement will depend upon the type and degree of diversification, as well as upon the relationship among the business product lines. However, the variables analysed in this study show that few Mexican companies have sales in other countries.

For that reason, the authors conclude that the majority of Mexican companies that opt to diversify and operate internationally face challenges such as the distinct, associated costs that are due to the companies’ inexperience in foreign markets, as well as to the institutional restrictions in emerging markets. However, some of the results presented here indicate that over time, as the companies gain understanding and experience, they become able to take advantage of the benefits-including higher profits-of a greater international diversification. It is necessary to explore the results that these companies obtain to find out whether the benefits are maintained over time. To that end, it is also necessary to understand each company’s needs and resources, along with the objective that it pursues in order to increase its value and reach its desired goal. Too, it is important to recall that several authors (Kim et al., 1993; Pangarkar, 2008) agree that diversification at the international level can bring a variety of benefits. For example, brand recognition at the international scale, a larger operating territory, and the ability to make use of economies of scale.

The authors add that a strategy such as the above will be effective, whether on the national level or the international, for any company that knows how to implement and manage it. Otherwise, the costs and disadvantages can at some point harm the company. A company must also know how and when decide to diversify.