1. Introduction

The World Tourism Organization [UNWTO], 2018, recognizes that one out of every ten jobs in the world is generated through some activity related to tourism, making it the second-largest productive sector. According to the National Institute of Statistic and Geography (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía [INEGI]), 2019, the tertiary sector employs more than half of Mexicans in Mexico. In the tourism activity, there is a huge volume of human resources concentrated in the hotel industry.

The problem presented by TJ frames differences between developing and developed countries since, for the latter, tourism represents a conquest of free time and leisure. At the same time, for the others, it is the employment-generating activity where work is available for the population but subject to conditions imposed by the international corporations of those developed countries (Coll-Hurtado and Córdoba, 2006).

The term QWL emerges from the systematic and scientific concern about the impact of these jobs on human beings and companies’ development. This is a multifactorial concept that integrates objective elements (material welfare, harmonious relations with the environment and society) and subjective elements (emotional expression, perceived safety, personal productivity, and perceived health of the worker), which leads man to feel healthy, productive, safe, and capable (Gómez and Sabeh, 1995).

Within this framework, the present research aims to analyze the influence of TJ on the QWL of the hotel staff in the city of Querétaro, Mexico. This study is relevant for the tourism field because it presents information that helps to improve the working conditions of the sector. The document presents an introduction of the hypothetical model, the methodology followed in the study, the treatment and analysis of data, the discussion, conclusions, and future lines of research.

2. Literature Review

Some studies point out that outsourcing has rapidly increased, in such a way that the labor market does not offer real opportunities besides the low-quality employment prevailing due to high demand (Coll-Hurtado and Córdoba, 2006). Tourism is a labor activity made up mostly of women performing vulnerable and low-paying activities (Costa, Lykke, and Torres, 2014; Carrillo, 2017; Moreno and Cañada, 2018). Likewise, it employs minors and students who represent an important workforce during holiday seasons. Additionally, it employs specific ethnic and cultural groups with minimal representation, as discrimination prevails and does not allow them to occupy important positions in companies in the sector (Albarracín and Castellanos, 2013; Sigüenza, Brotons, and Huete, 2013).

This activity presents a working model that is detached from international labor standards. It is made up of flexible, low-quality jobs, temporary contracts, high working hours, shift rotation, with low wages and benefits (Huízar, Villanueva, and Rosales, 2016; Méndez, Juárez, and Hernández, 2015). These conditions increase productivity under an economic model that aspires to growth and competitiveness supported by labor precariousness (Hernández, Vargas, Castillo, and Zizumbo, 2018), contributing to deep social and economic inequalities (ILO, 2017; Robinson, Martins, Solnet, and Baum, 2019).

The Mexican Federal Labor Law (2019) mentions that a decent job fully respects human dignity, gives access to social security, and receives a remunerative wage. However, in the last decades, TJ went from being a menial job to being part of a salaried job in a simulated way, diminishing the individual in the use of their free time, health, family, and work relationships (Garazi, 2016; Sánchez and Olivarría, 2016). In such a way that, as De la Garza (2009) points out, these types of fragmented jobs are incapable of constituting collective or individual identities, much less security.

TJ continue to be exalted by the large number of jobs generated by the hotel industry. However, one characteristic is its instability due to seasonal dynamics (Guidetti, Pedrini, and Zamparini, 2020) being a stable employment a source of protection for workers (Tokman, 2006). In addition, there is evidence that professional training and experience contribute to this permanence (Hualde, Guadarrama, and López, 2016; Marrero, Rodríguez, and Ramos, 2016).

Kwahar and Iyortsuun (2018) bet on humanizing the work environment based on social relations, the remuneration and reward system, home-work balance, job security, training and opportunities for personal autonomy, and a safe and healthy environment. In the hotel industry, it is recognized that employees attach great importance to their job performance to ensure quality service (Netemeyer and Maxham, 2007) even though the workload generates an imbalance with the family (Bahar and Osman, 2020; Zhao and Qu, 2009), as well as low job satisfaction (Deery and Jago, 2015).

On the other hand, QWL appears to achieve the individual’s physical, mental, and social well-being, depending on his or her perception, based on his or her level of happiness, satisfaction, and sense of reward (Ardilla, 2003). Moreover, as it is a multidimensional concept, it also includes man’s material and spiritual well-being in a social and cultural framework (González, Santacruz, and Estrada, 2007). Therefore, QWL constitutes one of the challenges within organizations since the individual, through work, sees his basic and non-basic needs covered (Pidal, 2009) while considering the external environment as an element that affects these dimensions (Zohurul and Siengthai, 2009).

The measurement of QWL has been transformed over time. In the beginning, task dimensions were evaluated (Oldham and Hackman, 1976), and later, it was analyzed through environmental and human values (Walton, 1985). Its study currently considers work in its multiple contexts, such as the individual’s behavior inside and outside the workplace, sharing the bases of organizational psychology (Oldham and Hackman, 1976; Walton, 1985). However, Cummings and Worley (2009) affirmed that QWL needs constant measurement to achieve its real and accurate implementation.

Recently, a conception has been integrated where the individual must develop holistically, mainly under the satisfaction of a wide range of needs: recognition, job-family balance, and motivation, among others (Ardilla, 2003; Zohurul, and Siengthai, 2009; Argüelles, Quijano, Fajardo, Magaña, and Sahuí, 2014; Molina, Pérez, Lizarraga, and Larrañaga, 2018).

Likewise, attempts are being made to explain the role of QWL and its link with productivity and competitiveness (Yeh, 2013); with work engagement (Yirik and Babür, 2014; Zopiatis, Constanti, and Theocharous, 2014), with emotional intelligence (Demir, 2011), corporate social responsibility (Carrasquilla and Centeno, 2015; Vargas, 2015), tourism business performance (Molina et al., 2018), and the financial performance and economic prosperity of hotels (Borralha, Neves, Pinto, and Viseu, 2016).

In the face of labor-intensive, contact-intensive tourism jobs, the study of QWL focuses on the satisfaction of the individual (Bednarska, 2013; Kruger, 2014; Kwahar and Akuraun, 2018). Lee, Back, and Chan (2015) associated job satisfaction with personality and human motivation, considering that support from co-workers and boss is an important factor for job satisfaction, increasing QWL (Avci, 2017; Ratna, Gde-Bendesa, and Antara, 2019).

Specifically, Zhao and Qu (2009) analyzed the conflicts caused by work interference with the family, recommending companies to integrate programs to develop personnel and their tasks with the family environment. On the other hand, Lewis and Gruyère (2010) considered that a flexible schedule and mutual relationships should positively affect the well-being of employees. Lin, Wong, and Ho (2013) proposed a system of leisure benefits as the main moderator. Real, García, and Piloto (2012) recognized the workplace’s ergonomic and physical aspects, organization, and safety factors.

In the hotel sector, the QWL has been evaluated through dimensions such as remuneration, stability, social security, and working hours (Huízar et al., 2016), reaching a balance between this and the tasks (Hofmann and Stokburger-Sauer, 2017). In addition, some models integrate equal opportunities, growth, equity, and compensation, being responsible for attracting and retaining the best talent and managing to keep them in the long term in the organization (Ambardar and Singh, 2017). Also, job security and benefits are important factors of QWL (Ratna et al., 2019).

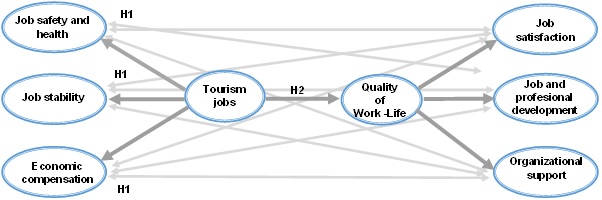

The theoretical model consisted of two variables with three dimensions each; for TJ: 1) job safety and health, 2) job stability and 3) economic compensation; and for QWL: 1) job satisfaction, 2) job and professional development, and 3) organizational support; as shown in Figure 1.

3. Materials and Methods

The research had post-positivist epistemological foundations insofar as it seeks to go beyond a mechanistic object by having an empirical object that is part of reality. The quantification of data can find a behavior trend of the variables (tourism jobs and quality of work-life). Hence, the research is based on the quantitative approach, with a cross-sectional, non-experimental design. The data were collected in a single period, and no variables were manipulated; rather, the phenomenon is presented as it was observed in reality. The scope is explanatory since, in addition to considering the relationship between the variables, the influence of the dimensions of tourism jobs on the quality of work-life is explained.

Therefore, the following research hypotheses are proposed:

H 1 : There is a significant and positive relationship between the dimensions of tourism jobs (job safety and health, job stability and, economic compensation) and the dimensions of the quality of work-life (job satisfaction, job and professional development and, organizational support).

H 2 : Tourism jobs have a significant and positive influence on the quality of work-life.

After reviewing the literature and analyzing the conceptual-theoretical construct, we defined the variables and determined their operationalization (Table 1). We designed and applied a questionnaire divided into two parts. In one part, we integrated the sociodemographic variables (age, gender, marital status, educational level, economic dependents, shift, position, personnel in charge, salary, seniority, number of current jobs, and type of contract), and in the other, we gathered the items that assess the employees’ perception of TJ and the QWL in the hotel industry, with a 6-point Likert scale, where (1) means totally disagree to (6) which is totally agree.

Table 1 Operationalization of Variables

| Variable | Dimension | Item | ID |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tourism Jobs (TJ) Job that is generated to satisfy tourist demand, offering security, stability and competitive remuneration. | Job safety and health: Employee’s perception of the set of measures aimed at the prevention, protection and elimination of risks that endanger their health, life or physical integrity. | Safety at job facilities | Item_11 |

| The workplace has safety measures in place | Item_12 | ||

| Accidents are rare at job | Item_13 | ||

| The hotel provides food for the staff | Item_14 | ||

| The workplace is clean, hygienic and healthy | Item_18 | ||

| Job stability: Employee’s perception of the certainty of retaining employment and remaining in their job. | Security against unjustified dismissal | Item_28 | |

| Enthusiasm for working in the organization | Item_29 | ||

| Stable work | Item_30 | ||

| Stability in the face of low seasons | Item_31 | ||

| There is communication with staff in all areas | Item_32 | ||

| Economic compensation: Employee’s perception of receiving adequate economic remuneration for the knowledge and skills possessed and successfully applied to their work activities. | Satisfaction with the economic compensation | Item_25 | |

| The salary corresponds to the activities performed | Item_26 | ||

| Salary is commensurate with knowledge and skills | Item_27 | ||

| Quality of Working-Life (QWL) Quality of life is located in the area of satisfaction of needs and human development; it is, therefore, a subjective well-being that includes aspects such as recreation, recognition, participation, knowledge, and skills, among others. | Job satisfaction: Employee’s perception of his or her job, activities performed, relationships between colleagues, work-family balance and work environment. | Satisfaction with performance | Item_01 |

| Satisfaction with the freedom to work | Item_02 | ||

| Satisfaction about the activities you perform | Item_03 | ||

| Enjoy your leisure time without affecting work | Item_04 | ||

| After work you have time to enjoy your family | Item_05 | ||

| Work makes you feel happy and positive | Item_15 | ||

| The workplace is pleasant | Item_16 | ||

| Work is comfortable to perform your tasks | Item_17 | ||

| The social environment at work is warm and pleasant | Item_19 | ||

| The tasks performed are stimulating | Item_20 | ||

| The activities performed have a positive impact | Item_21 | ||

| Skills and abilities are applied | Item_22 | ||

| Experience and knowledge are increased | Item_23 | ||

| Sense of productivity in the face of results | Item_24 | ||

| Relationships with co-workers | Item_33 | ||

| Job and professional development: Opportunities that the hotel offers employees to apply and develop their skills, allowing them to learn and reinforce their knowledge, as well as the possibility of promotion. | There is support for a family emergency | Item_06 | |

| Opportunity for job coaching | Item_07 | ||

| Opportunity for promotion to better positions | Item_08 | ||

| Development of skills and abilities | Item_09 | ||

| Support from superiors for job and professional development | Item_10 | ||

| Confidence in skills to interact with customers | Item_34 | ||

| Organizational support: Employee’s perception of feeling supported by the organization and their superiors, receiving the necessary information to improve their performance and performance. | Guidance for the work performed | Item_35 | |

| Information on achievements at job | Item_36 | ||

| Reports on job performance | Item_37 | ||

| Recognition for the work performed | Item_38 | ||

| The hotel supports proposals to achieve goals | Item_39 | ||

| Professional objectives are supported | Item_40 | ||

| The hotel supports the needs of employees | Item_41 |

Source: Authors’ own elaboration.

The instrument was subjected to the review of academic experts and to a pilot test of 40 subjects, from which adjustments were made to the instrument’s items. The questionnaire was applied to hotel workers in Querétaro, Mexico, during the second semester of 2019 and the first semester of 2020.

The statistical tests of reliability (Cronbach’s alpha) and validity (exploratory factor analysis) were satisfactory; overall, the dimensions presented a cumulative explained variance of 74.57% and acceptable levels of internal consistency (Table 2). Thus, it was possible to continue with the average comparison and correlation analyses (Pearson coefficient) and the linear regression analysis.

Table 2 Factor Analysis and Variance

| Item | Dimension | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Job safety and health | Job stability | Economic compensation | Job satisfaction | Job and professional development | Organizational support | |

| Item_11 | 0.775 | |||||

| Item_12 | 0.819 | |||||

| Item_13 | 0.718 | |||||

| Item_14 | 0.633 | |||||

| Item_18 | 0.668 | |||||

| Item_28 | 0.577 | |||||

| Item_29 | 0.715 | |||||

| Item_30 | 0.688 | |||||

| Item_31 | 0.655 | |||||

| Item_32 | 0.460 | |||||

| Item_25 | 0.729 | |||||

| Item_26 | 0.831 | |||||

| Item_27 | 0.804 | |||||

| Item_01 | 0.703 | |||||

| Item_02 | 0.622 | |||||

| Item_03 | 0.740 | |||||

| Item_04 | 0.701 | |||||

| Item_05 | 0.543 | |||||

| Item_15 | 0.705 | |||||

| Item_16 | 0.688 | |||||

| Item_17 | 0.639 | |||||

| Item_19 | 0.574 | |||||

| Item_20 | 0.611 | |||||

| Item_21 | 0.613 | |||||

| Item_22 | 0.710 | |||||

| Item_23 | 0.672 | |||||

| Item_24 | 0.622 | |||||

| Item_33 | 0.543 | |||||

| Item_06 | 0.472 | |||||

| Item_07 | 0.512 | |||||

| Item_08 | 0.743 | |||||

| Item_09 | 0.724 | |||||

| Item_10 | 0.681 | |||||

| Item_34 | 0.559 | |||||

| Item_35 | 0.770 | |||||

| Item_36 | 0.778 | |||||

| Item_37 | 0.844 | |||||

| Item_38 | 0.753 | |||||

| Item_39 | 0.627 | |||||

| Item_40 | 0.707 | |||||

| Item_41 | 0.627 | |||||

| Cronbach’s alpha | 0.896 | 0.915 | 0.914 | 0.961 | 0.908 | 0.932 |

| % Variance explained | 4.605 | 3.861 | 3.017 | 51.392 | 6.309 | 5.388 |

| % Cumulative explained variance | 4.605 | 8.466 | 11.483 | 62.875 | 69.184 | 74.572 |

Source: Authors’ own elaboration.

3.1. Sample

The sample was non-probabilistic and consisted of 156 workers from hotels in Querétaro. The selection was conformed by volunteers since it was not possible to extract a random probability sample due to the onset of the pandemic. The participants were young people between 18 and 35 years of age (64.1 %), with the female gender standing out with a little more than half of the sample and 62.8% were single. Regarding their educational level, 27.6% completed secondary school, 24.4% completed high school, and 26.9% completed a bachelor’s degree. This shows the national reality of the tourism sector, which has been mentioned in other studies, where a large part of the workers only has basic education.

The majority of the workers economically support one or two people; 46.8% work a mixed shift. 62.2% are operational personnel, so they do not manage their staff. Also, 60% receive a monthly salary of between 3,700.00 and 7,000.00 Mexican pesos (between US$200.00 and US$350.00). On the other hand, 46.8% of the respondents have been working for less than one year. However, a little more than half (56.4%) have an indeterminate contract, and 75% of the respondents only generate income under this labor activity (Table 3).

Table 3 Sample Description

| Variable | Value | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 18 - 25 | 31.4 |

| 26 - 35 | 32.7 | |

| 36 - 45 | 12.8 | |

| 46 - 55 | 15.4 | |

| 56 - 65 | 7.1 | |

| over 65 years old | 0.6 | |

| Gender | Feminine | 54.5 |

| Masculine | 45.5 | |

| Marital status | Single | 62.8 |

| Married | 37.2 | |

| Educational level | Primary | 11.5 |

| Secondary | 27.6 | |

| High school | 24.4 | |

| Technical career | 7.7 | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 26.9 | |

| Other | 1.9 | |

| Number of economic dependents | None | 36.5 |

| 1 - 2 | 43.6 | |

| 3 - 4 | 16.7 | |

| Over 5 | 3.2 | |

| Job shift | Morning | 39.7 |

| Afternoon | 12.8 | |

| Night | 0.6 | |

| Mixed | 46.8 | |

| Position in the hotel | Executive position | 17.3 |

| Administrative position | 20.5 | |

| Operational position | 62.2 | |

| Do you have personnel in your charge? | Yes | 26.9 |

| No | 73.1 | |

| Monthly salary (in Mexican pesos) | $3 700 - $7 000 | 62.2 |

| $7 001 - $11 000 | 22.4 | |

| $11 000 - $15 000 | 12.2 | |

| $15 000 - $19 000 | 3.2 | |

| Seniority in current position | Less than one year | 46.8 |

| 1 - 3 year | 31.4 | |

| 4 - 5 year | 6.4 | |

| Other | 15.4 | |

| Current jobs | Only one | 75.0 |

| 2 - 3 | 18.6 | |

| Over 3 | 6.4 | |

| Contract | Undetermined time | 56.4 |

| Seasonal | 12.8 | |

| Per project | 5.1 | |

| Other | 25.6 |

Source: Authors’ own elaboration.

In short, this is a labor group of young people and young adults, single, with a high school to bachelor’s degree education, with little seniority in the company where they work, occupying operational positions, most of them with an income of less than 7,000 Mexican pesos.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

When analyzing the arithmetic means of the dimensions that make up the tourism jobs variable, it is observed that the workers’ perception is positive but at a low level (x̄ = 3.90 to x̄ = 4.53). However, a negative valuation is observed for economic compensation. Something similar occurs with the dimensions of the QWL variable (x̄ = 4.09 to x̄ = 4.47), which values barely exceed “moderately agree”. Consequently, the perception of tourism jobs is affected by the received salaries, and the quality of work-life presumes little support for recognition of performed work and proposals for goals achievements (Table 4).

Table 4 Descriptive Analysis

| Item | Mean | Standard deviation | Dimension | Mean | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item_11 | 4.685 | 1.703 | Job safety and health | 4.538 | 1.711 |

| Item_12 | 4.628 | 1.756 | |||

| Item_13 | 4.230 | 1.733 | |||

| Item_14 | 4.288 | 1.788 | |||

| Item_18 | 4.859 | 1.575 | |||

| Item_28 | 3.903 | 1.896 | Job stability | 4.207 | 1.811 |

| Item_29 | 4.192 | 1.803 | |||

| Item_30 | 4.365 | 1.685 | |||

| Item_31 | 4.320 | 1.788 | |||

| Item_32 | 4.256 | 1.883 | |||

| Item_25 | 4.051 | 1.751 | Economic compensation | 3.903 | 1.826 |

| Item_26 | 3.833 | 1.886 | |||

| Item_27 | 3.826 | 1.842 | |||

| Item_01 | 4.532 | 1.874 | Job satisfaction | 4.478 | 1.711 |

| Item_02 | 4.250 | 1.854 | |||

| Item_03 | 4.474 | 1.643 | |||

| Item_04 | 4.269 | 1.705 | |||

| Item_05 | 3.916 | 1.917 | |||

| Item_15 | 4.564 | 1.611 | |||

| Item_16 | 4.737 | 1.634 | |||

| Item_17 | 4.711 | 1.594 | |||

| Item_19 | 4.480 | 1.624 | |||

| Item_20 | 4.352 | 1.721 | |||

| Item_21 | 4.647 | 1.593 | |||

| Item_22 | 4.506 | 1.728 | |||

| Item_23 | 4.589 | 1.799 | |||

| Item_24 | 4.634 | 1.610 | |||

| Item_33 | 4.506 | 1.757 | |||

| Item_06 | 4.391 | 1.794 | Job and professional development | 4.423 | 1.805 |

| Item_07 | 4.487 | 1.754 | |||

| Item_08 | 4.230 | 1.930 | |||

| Item_09 | 4.506 | 1.801 | |||

| Item_10 | 4.583 | 1.766 | |||

| Item_34 | 4.339 | 1.787 | |||

| Item_35 | 4.243 | 1.822 | Organizational support | 4.096 | 1.889 |

| Item_36 | 4.096 | 1.848 | |||

| Item_37 | 4.096 | 1.879 | |||

| Item_38 | 3.897 | 1.908 | |||

| Item_39 | 3.903 | 1.992 | |||

| Item_40 | 4.192 | 1.887 | |||

| Item_41 | 4.243 | 1.888 |

Source: Authors’ own elaboration.

The sociodemographic variables show that both men and women appreciate the dimensions under evaluation in the same way, so there are no significant gender differences. In terms of marital status, single people appreciated better than married people the dimensions of job stability, job and professional development, and organizational support (P < 0.050) (Table 5).

Table 5 T-Student and ANOVA

| Dimension | T Student | ANOVA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Marital status | Age | Educational level | Position | Seniority | |

| Job safety and health | 0.879 | 0.407 | 0.008 | 0.025 | 0.009 | 0.188 |

| Job stability | 0.067 | 0.009 | 0.278 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.166 |

| Economic compensation | 0.211 | 0.071 | 0.427 | 0.005 | 0.035 | 0.894 |

| Job satisfaction | 0.072 | 0.098 | 0.230 | 0.004 | 0.000 | 0.420 |

| Job and professional development | 0.076 | 0.047 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.810 |

| Organizational support | 0.593 | 0.039 | 0.006 | 0.149 | 0.006 | 0.776 |

Source: Authors’ own elaboration.

Regarding educational level, workers with bachelor’s degrees gave the highest values for job satisfaction (x̄ =4.47, σ=1.711), job and professional development (x̄ = 4.42, σ=1.805), job stability (x̄ =4.20, σ=1.811), and job safety and health (x̄ = 4.53, σ=1.711). In contrast, personnel with primary and secondary education gave lower values.

On the other hand, age does not play a role in significant differences in job stability, economic compensation, or job satisfaction. However, it does play a role in job safety and health, job and professional development, and organizational support, with the youngest employees having the best evaluations of these dimensions, while the groups aged 36 to 45 years and 56 to 65 years are the ones with the lowest perceptions.

Another variable that significantly intervenes in evaluating all the dimensions was the position held within the hotel. Those with administrative positions evaluated the tourism jobs better (x̄ = 5.01) and the quality of work-life (x̄ = 5.10), followed by the managerial and operational positions, even though the latter represents 62.2% of the sample.

There is also evidence of inequality between perceptions according to educational level; those with higher education have a better appreciation of TJ and QWL. Age and marital status are also representative variables of the opinions on the quality of work-life in hotels.

4.2. Correlational Analysis

Table 6 shows the correlations between the QWL and TJ dimensions; all are highly significant, positive, and of moderate and high strength. It can be noticed that safety and health, the first dimension of the TJ, maintains a strong positive relationship with job satisfaction (r = 0.685, P ≤ 0.010) and job and professional development (r = 0.667, P ≤ 0.010); while with organizational support (r = 0.509, P ≤ 0.010) the association is moderate positive. The same is true for job stability, whose relationships are the strongest, particularly with job satisfaction (r = 0.775; P ≤ 0.010). The third dimension, economic compensation, also maintains positive and moderate associations, where again, job satisfaction turned out to be the highest (r = 0.588, P ≤ 0.010).

Table 6 Pearson Correlations

| Dimension | Job safety and health | Job stability | Economic compensation | Job satisfaction | Job and professional development | Organizational support |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tourism Jobs (TJ) | ||||||

| Job safety and health | 1 | |||||

| Job stability | 0.559** | 1 | ||||

| Economic compensation | 0.475** | 0.668** | 1 | |||

| Quality of Work-Life (QWL) | ||||||

| Job satisfaction | 0.685** | 0.775** | 0.588** | 1 | ||

| Job and professional development | 0.667** | 0.675** | 0.538** | 0.755** | 1 | |

| Organizational support | 0.509** | 0.651** | 0.513** | 0.647** | 0.668** | 1 |

** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (bilateral).

Source: Authors’ own elaboration.

4.3. Explanatory Analysis

As shown in Table 7, the three models emanating from the dependent variable QWL: I) job satisfaction, II) job and professional development, and III) organizational support, are significant since there is a fit of the data with the sample to explain reality. On the other hand, the Durbin-Watson statistic and the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) were tested to ensure that there are no problems of autocorrelation and collinearity among the variables.

Table 7 Multiple Linear Regression

| Independent variable: TJ | Dependent variable: Quality of Work-Life (QWL) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model I Job satisfaction | Model II Job and professional development | Model III Organizational support | ||||||||||

| Standardized beta | Sig. | Tolerance | VIF | Standardized beta | Sig. | Tolerance | VIF | Standardized beta | Sig. | Tolerance | VIF | |

| Job safety and health | 0.359 | 0.000 | 0.478 | 2.093 | 0.414 | 0.000 | 0.478 | 2.093 | 0.196 | 0.008 | 0.478 | 2.093 |

| Job stability | 0.542 | 0.000 | 0.538 | 1.858 | 0.311 | 0.000 | 0.538 | 1.858 | 0.471 | 0.000 | 0.538 | 1.858 |

| Economic compensation | 0.059 | 0.330 | 0.669 | 1.496 | 0.102 | 0.193 | 0.669 | 1.496 | 0.105 | 0.199 | 0.669 | 1.496 |

| R | 0.841 | 0.711 | 0.678 | |||||||||

| R2 | 0.707 | 0.505 | 0.460 | |||||||||

| R2 aj | 0.701 | 0.495 | 0.449 | |||||||||

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||||||||

| Durbin Watson | 2.117 | 1.749 | 2.063 | |||||||||

Source: Authors’ own elaboration.

In particular, Model I shows that the greatest influence has job stability (β = 0.542; P < 0.010), indicating that not being unjustifiably dismissed, and remaining in employment, regardless of low seasons, will increase job satisfaction, impacting the perception of employees in aspects such as: performing their work in freedom, enjoying leisure activities and free time with the family.

Similarly, in Model II, job safety and health have the greatest influence on job and professional development (β = 0.414; P < 0.010), indicating that the attributes of facilities, safety, and hygiene measures, and the fact that benefits such as food are provided, have a positive impact on the development of their functions; which contributes to the worker having greater confidence to develop their activities (Kwahar and Akuraun, 2018).

Finally, in Model III, job stability stands out again, having the strongest influence on organizational support (β = 0.471; P < 0.010). Showing that confidence about their permanence in the position allows improving aspects about their tasks, supporting improvement proposals, and boosting their professional careers within the organization, as pointed out by Huízar et al. (2016).

Based on the results, it is conjectured that the three models are significant and support the idea that TJ has an impact on QWL since the regression values validate the established assumption.

5. Discussion

This research shows that TJ and QWL in Querétaro hotels are positively valued but low. Job stability has a strong influence on job satisfaction, speaking of the uncertainty felt by workers regarding unjustified dismissal and job permanence during low tourism seasons (Huizar et al., 2016). One of the main determinants of QWL is obtaining a stable job, as demonstrated by Marrero et al. (2016). In addition to indicating that stability is usually linked to high levels of education, similar to the results of Carvalho et al. (2014) and Hualde et al. (2016). Contrary to expectations, this study found no significant difference in perception between men and women regarding QWL dimensions.

Hotels should be more concerned about the work environment and working hours that limit employees’ family time. This finding supports previous research by Zhao and Qu (2009) and Bahar and Osman (2020), increasing workers’ satisfaction. Likewise, opportunities for further training, along with the support provided by hotels to do so, significantly increases job performance (Netemeyer and Maxham, 2007). Authors such as Braverman (1981) and de la Garza (2009) warn that the implications of visualizing the individual only from the strength of their work and the creation of capital generate a collective and individual fragmentation, which leads to a decrease in their capacity for positive action within the company, generating job dissatisfaction.

As stated in another research (Zohurul and Siengthai, 2009; Yirik and Babür, 2014), it is confirmed that there is a significantly positive correlation between job development, economic compensation, organizational support, and safety and health, reaffirming that these support job satisfactions. Emphasizing that job stability generates leisure benefit systems, as the main moderator of their motivation and communication with all areas, influencing the increase in job satisfaction and impacting on the improvement of employees’ perception in aspects such as freedom to work, leisure activities, and free time with the family (Demir, 2011; Lin et al., 2013). Support from peers and superiors increases work development and QWL (Avci, 2017; Ratna et al., 2019).

This suggests the desirability of supporting employees by making family and work roles compatible (Garazi, 2016; Sánchez and Olivarría, 2016). It may also be particularly relevant in this industry, as employees generally face long hours in rotating shifts, night weekends, and holiday shifts (Harris, Winskowski, and Engdahl, 2007); they also face a lack of job security and low-skilled jobs.

In the case of workers in hotel companies in Querétaro, job stability and job safety and health are valued more than economic compensation, confirming that the tourism sector does not offer the most competitive salaries compared to other productive activities (Carrillo, 2017). However, these factors become relevant to the extent of providing secure work, especially in situations of unemployment and economic crisis (Ratna et al., 2019).

6. Conclusions

In general terms, hotel workers in Querétaro perceive that the organization moderately satisfies their needs related to QWL; the same is true for the dimensions of TJ, except for the economic compensation, which for the majority of the personnel does not meet their expectations.

There are relationships between the dimensions of the two variables. There is also evidence of an influence of TJ on QWL, although not directly, but as a whole, this supports the fulfillment of the main objective of the research. Hotels could implement initiatives to promote the promotion of their workers to better jobs, decision making, training, and support strategies from their superiors to fulfill professional goals and processes that inform, recognize, and support the contributions that each collaborator makes.

The hypothesis of correlation between the dimensions of the TJ and QWL is tested, concluding that they are present, positive, and moderate-strong. Likewise, although not directly tested, the hypothesis of influence supports its verification, fulfilling the main objective of the research.

For future studies, it is important to consider the multidimensional nature of the QWL variable and to analyze it in contrast with the determinant indicators of each organization or hotel company to develop studies that continue to demonstrate the correlation and influence between both variables.

The research was able to identify aspects of QWL that hotels could improve. Among these are initiatives to promote promotion for better jobs, decision making, training for the development of skills and abilities of staff, as well as support strategies from superiors for the fulfillment of professional goals of workers, through the implementation of processes that inform, recognize, and support the contributions that each employee makes.

Tourism is an economic axis that increasingly strengthens the country; therefore, the research approach showed the sector’s importance, which should be an incentive for future studies that allow the recognition of the same to generate strategies that allow its application in the hotel labor field.