1. Introduction

Diversity covers ethnicity, sex, and religion as well as other demographic realities such as age, education, and personality. Therefore, diversity is not only about integrating minorities by legal requirement (Chinchilla and Cruz, 2011); it is also about the inclusion to the world of work of both individuals in vulnerable conditions and those who, after having belonged to groups outside the law, have at a later point decided to decommission their arms and reintegrate into civilian life. Knowing how to successfully manage this type of population thus becomes a challenge for companies. Two main actors have been identified through research on groups undergoing the reintegration process: guerrilla groups, and paramilitary groups, which surfaced due to several political and economic factors (Hernández García De Velazco, Chumaceiro Hernández, Ziritt Trejo, and Acurero Luzardo, 2018).

For many years, an interest in solving armed conflicts through negotiations to achieve peace within different countries has emerged across the world. All confrontations and peace agreements have marked the social and cultural fabric: the collective imaginaries have been influenced through public conversations around peaceful coexistence, redefining the relationships between the State and society at large by means of different governments’ public policies for the construction of social peace (Giraldo, 2010). As a result, several peace processes that have allowed many ex-combatants to re-join civilian life by reinstating their fundamental rights, including work, have been developed through their public agenda. The peace agreements with the April 19 Movement (M19), the Workers’ Revolutionary Party (PRT), the People’s Liberation Army (EPL), the Quintín Lame Armed Movement, the United Self-Defense of Colombia (AUC - Paramilitaries), and the latest with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, the People’s Army (FARC-EP), stand out among others (García and Arana, 2018).

Although some individuals have managed to reintegrate into society, very difficult and complex situations persist in terms of attempting to enter civilian life and the work sphere providing them adequate conditions to achieve an optimal human development; this has led to said individuals’ rearmament and, therefore, to an increase of violence in urban centers. Thus, labor inclusion constitutes an emancipatory mechanism from violence in Colombia. It is a public policy tool to promote the socialization of the country’s illegal armed groups (Roldan, 2013); it becomes a strategy for individuals in the reintegration process to achieve their goals regarding quality of life, and for not relapsing into crime (Cristancho and Buitrago, 2018). According to the legal system, it is the state’s responsibility to create policies for job creation, especially if it concerns the enforcement of this right for individuals whose life circumstances have been and continue to be quite different to those of an ordinary citizen (Pedreros, 2016). The Colombian government has issued several regulations to support reintegration processes, among which the following stand out: Legislative Act 03 of 2017 (FARC political reinstatement); Decree Law 894 of 2017 (Provisions regarding public employment); Decree Law 897 of 2017 (Restructuring of the Agency for Reintegration); and Decree Law 899 of 2017 (Measures for social and economic reintegration) (Consejo Nacional de Política Económica y Social -CONPES-, 2008).

A significant number of demobilized individuals in need of engaging in civilian life and the labor market resulted from the policies promoted by the state. In this connection, the Agency for Reincoporation and Normalization (ARN) has played an important role in the employment of these individuals by businesses in the country.

As explained before, and despite the creation and implementation of programs by the state for the labor inclusion of demobilized individuals, numerous problems and challenges remain. Most of these individuals have a low educational level and little experience in the world of work; besides, they are poorly accepted by society to be employed in a dignified and sustainable way (Ríos, Valbuena, and Castañeda, 2019). Similarly, the country has its shortcomings at the administrative level, as well as political conflicts and a lack of commitment from the negotiating parties which do not allow for an adequate and definite implementation of peace agreements that build trust in all actors -including victims and civil society- so that a real and true sustainable labor inclusion of ex-combatants be accomplished.

This study is hence justified as it aims to identify and describe the strategies that some Colombian companies are currently using for the labor inclusion of ex-combatants. Both positive aspects and those requiring further improvement are considered. Based on experiences, this study also aims to lay the foundations for the implementation of improvements to public policy in Colombia in such a way that the trust needed is built between employers and society at large, leading to these individuals’ access to the labor market (Roldán, 2013).

2. Theoretical Framework

Diversity cannot be defined as a singularity alien to the human being themself. Each being is inherently diverse; each person has peculiarities and characteristics that make them different from others. Therefore, there are characteristics that, to a lesser or a greater extent, can influence labor relations and job performance: visible or external characteristics covering sociodemographic aspects such as sex, age, ethnicity, and physical abilities; and internal characteristics, including aspects such as training, trajectory, values, beliefs, attitudes, and sexual, political, or religious preferences (Ágreda, García, and Rodríguez, 2016). When diversity is managed properly, it can become a competitive advantage for the organization (López Velásquez, Rico Balvín, Gómez Peláez, Bermúdez Correa, Mejía García, Colorado Castillo, … and Aristizábal García, 2016). The term diversity is applicable to the concept of demobilized person since it meets the condition of being -within the internal characteristics- a specially defined population. To the Colombian State, a demobilized individual is any person who, having been part of an armed group outside the law, has ceased to be an active member of it and has surrendered to the relevant authorities either collectively or individually (Rodríguez and Espinosa 2018). Diversity is relevant from the business perspective when it affects people’s relationships; this means the challenge for organizations is to develop a culture that enables the identification of objectives and functions aligned with diversity, where all members are valued (García-Morato, 2012).

Regarding demobilized individuals, evidence shows they are marked by psychosocial prejudice and values and behavioral patterns internalized by the subversive groups, preventing them from adapting to the world of work. Furthermore, they tend to have low levels of training and insufficient education or experience that hinders their formal engagement in different work activities. Given that many of these individuals are settled in belts of misery, competing for resources with other vulnerable communities can result in new confrontations when ex-combatants are assisted by the State (Rodríguez and Espinosa 2018). Labor inclusion of demobilized individuals must thus be considered an end because its ultimate goal is to give workers the opportunity to access formal employment as well as a means, because the demobilized individual is reincorporating into society (Cárdenas, Navarro, and Angulo, 2017). In short, labor inclusion is an emancipatory mechanism from violence, which in turn faces obstacles, namely the demands of the labor market, discrimination, and rejection (Nussio, 2013). These shortcomings create an environment leading to the demobilized individual’s recidivism in criminal activities (Garcia, 2015).

Reintegration is the process through which the demobilized have access to the social and economic offer of the State. They are offered support to improve their quality of life and that of their families; they acquire civilian status in addition to obtaining employment and a sustainable income (Peña and Medina, 2018). On the other hand, the individual and their dependents are committed to overcoming their situation and remaining lawful.

Although work climate and job satisfaction are two different constructs, they are linked. The former refers to information pertaining to organizational characteristics, while the latter places emphasis on the attitudes and perceptions that individuals have towards their work (De Paula and Queiroga, 2015). Consequently, the great challenge for the human management area consists in assigning an integral position to the human being, with their multidimensional character, placing them at the core of the organizational dynamics. This is linked to the integral human development of individuals and the impact of their own actions on others, which results in learning from successive interactions and an increase in internal and external trust (Bermejo and Durban, 2018). It reduces the distance that separates “us” (the leaders) and “them” (those who are being led) and overcomes resistance to the bridging of gaps relating to the subordinated relationship structure within organizations (Manosalvas Vaca, Manosalvas Vaca, and Nieves Quintero, 2015). For this reason, managing the work climate becomes a key factor for the development and achievement of organizational objectives supporting inclusion processes. In turn, work climate is influenced by job satisfaction -the positive attitude that a person experiences in performing a job when they are qualified, motivated, and satisfied to fulfil their duties adequately (Salessi, 2014; Domínguez, Ramírez, and García, 2013).

Sense of work is related to each employee’s experience and alludes to internal psychological states and processes of a cognitive nature that define an employee’s perception of themself and the work context in which they are embedded (Orgambídez, Pérez and Borrego, 2015). Along the same lines, culture, the relationship with values, customs, ways of seeing reality, and contexts, also have implications on people’s working lives and their well-being (de Maldonado, 2016). The link with work varies according to the context and experiences the workers go through. In this process, the socialization experienced by the individual in each specific setting, in particular the family, is of great importance, as the latter influences the way in which work is subsequently approached (Ávila and Castañeda, 2015). Work fosters social integration and constitutes one of the ways in which life learning takes place in society; additionally, it enables the transformation of the world through the relationship with oneself, nature, and others (Romero Caraballo, 2017).

Work, diversity management, and satisfaction are undoubtedly aimed at sustainable development objectives (Gil, 2018). Therefore, in the context of post-conflict, human development is the ability of different actors to harmonize their interests, to transform cultural reality in order to guarantee rights. This being so, development will be enriched by diversity if focused on the human, making the transformation of society possible. Understanding this process hence increases people’s opportunities, including a long and healthy life, access to education and decent work, among many other guarantees (García and Arana, 2018). Sen (2000) enhances the notion of development from the perspective of the distribution of goods, the satisfaction of human needs and equity based on freedoms, capabilities, and delegation -establishing the idea of human development supported by the richness of human life rather than by economic wealth.

Given all of this, the Colombian state must define public policies to promote the labor inclusion of the country’s illegal armed groups through different mechanisms while society’s responsibility is to provide employment opportunities so that they can find lawful options to meet their needs (Roldán, 2013). By the same token, laws either obliging or at least giving benefits to companies for hiring this type of population are needed in when managing labor inclusion (Garavito, 2014). Human willingness from both the company’s management and the other individuals working in the company is also required (Sepúlveda Romero, Moreno Martínez, Tovar Mesa, Franco Villalba, and Villarraga Tole, 2015): no peace process is possible in a society with a deficient labor market where the resocialization of the demobilized is affected (Gómez, 2007).

3. Methodology

The present study was a descriptive research that used a mixed design (quantitative and qualitative) (Hernández and Torres, 2018). The companies under study belong to the commercial and financial sector and were selected intentionally, taking into account their trajectory in the process of hiring individuals in the reintegration process. The population under study was made up of three managers from the human management area and seventy-one employees registered in the training process of the Agency for Reintegration and Normalization (henceforth ARN). Both populations have employment links with three companies in the city of Medellín.

An interview for managers and a survey for employees were used as information gathering instruments, where qualitative dimensions including sustainable labor inclusion, fair recruitment, treatment, and administrative tools were analyzed. Quantitative dimensions covering work climate, satisfaction with the organization, experiences, and senses of work were also studied.

With respect to the information obtained from the interviews with managers, a qualitative content analysis was carried out assisted by the Atlas Ti software. The interview was reviewed by three experts, one of them a member of the ARN. The quantitative analysis of the results of the surveys designed with a Likert-type numerical scale and applied to employees was completed through the SPSS software and, for validity purposes, a correspondence greater than 0.30 and a significance between 0.000 and 0.005 were observed. The results indicated the correspondences are high among all the variables. As for reliability, Cronbach’s Alpha and Guttman’s Split-Half methods were used, yielding coefficients greater than 0.70 in all variables.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Qualitative analysis

4.1.1. Labor inclusion programs for persons in the reintegration process: For the labor

Inclusion of persons undergoing the reintegration process (henceforth PRPs), it is necessary to define new recruitment processes that facilitate their hiring. López et al. (2014) argue that, in order to manage diversity, the following stages for labor inclusion must be followed: assessment, planning, training, communication, monitoring, and evaluation.

In this sense and following on the responses given by human management executives, the companies under study have defined strategies that facilitate the development of inclusion processes based on an assessment that is aligned with its main strategic ally -the ARN-, who refers the candidates according to the profile required by each of the companies. Planning is determined by inclusion programs with policies for a flexible recruitment process of PRPs. Training is provided through awareness workshops that foster individuals’ further growth; communication deals with keeping the PPR status exclusively between the ARN, the human management area, and senior management, as the idea is to create an atmosphere of trust between the company and the PPR. Monitoring and evaluation are a joint effort between the ARN and the hiring company and includes psychosocial support and academic training.

Flexibility in the recruitment processes was a common result found in all companies. Hiring PRPs would not be possible without differential policies at this stage of the recruitment process given their scarce academic training and work experience. It was also noted that companies have long-term projections aimed at successfully hiring a greater number of PPR, especially with the implementation of the peace process that the country is undergoing.

4.1.2. Equal working conditions:

The interviewed companies implement actions from human management to manage PRP diversity not only in relation to treatment but also in connection to the hiring and evaluation which, given their unique condition, are different to those for other recruited individuals. Labor inclusion processes are not about offering the same conditions but rather about offering the most appropriate ones for each population type (García-Morato (2012) describes the importance of designing a culture based on diversity, where all members are valued and objectives that allow for managing plurality are set in organizations. In this sense, the analysis of companies shows, through the inclusion programs that are in place, that although the hiring conditions must be differential to establish a successful work relationship with these individuals, the working conditions in terms of salary, responsibilities, duties, and commitments must be the same for any person working in those companies. However, differentiated monitoring and support are conducted because, as one of the companies points out, “the learning, socialization, and adaptation processes may be slower or different, so they are provided with plenty of support and monitoring.”

On the other hand, in relation to equal treatment, not labelling PRPs is treated as a cross-cutting pillar in the analyzed companies. This strategy has made it possible to reduce discrimination rates, achieve real inclusion, and strengthen trust between PRPs and companies.

The results obtained from the companies under study showed three key success factors in the PRP recruitment process: the recruitment and hiring stages, the effectiveness obtained, and abandoning paradigms with respect to the individual. In the recruitment and hiring stage, a common theme was revealed to take place in all three companies: they put a request to the ARN for the candidates required by them to fill the available vacancies. The companies were confident the individuals selected for the job opening have already made progress in the Agency program in addition to undergoing a process a posteriori. It was also evident that companies should implement non-traditional and more flexible recruitment processes so that PRPs can have access to more vacancies. This becomes a challenge for human management areas as they need to ensure the recruitment processes be fair and effective in the long term.

4.1.3. Strategic allies who make it possible for the labor inclusion of PRPs to be sustainable:

Synergies gain important momentum in the labor inclusion of PRPs because increasing organizations’ trust and being able to engage worthily in civilian life are sought through the alliances that are formed. Abarca (2010) notes that strategic alliances arise in the face of opportunities or uncertainties in the environment and companies needing to adapt to it. Therefore, an adequate synergy implies the responsibility of assessing the environment and the social, political, and economic conditions to contribute to important transformations, both at the business and at the country levels. The research results show that the human management areas of the companies interviewed are working hand in hand with the ARN, a key actor in the labor inclusion process of PRPs. From the peace and reconciliation program, the ARN has used different administrative tools that have facilitated interaction with different organizations; its work generates trust in relation to the individuals they refer for employment -they are provided with a psychosocial and academic support process which renders them suitable for the required profiles.

Furthermore, other entities such as SENA (The National Training Service), the Red Cross, the Victims’ Unit, the Secretariat of Economic Development from Medellín Mayor’s Office, the Welfare or Development and Social Action secretariats and some foundations were also found to work in support of the ARN’s work to make sure organizations start to overturn the paradigm surrounding the hiring of this population.

4.2. Quantitative analysis

4.2.1. Demographic dimension:

As shown in the results in Table 1, in relation to the total number of people surveyed, the balance between the percentage of men and women who are in the process of training for employment is very close. Regarding the age of demobilized individuals, ages ranging from 26 to 38 years are the most prevalent. Finally, demobilized individuals from FARC have the highest percentage of participation in the training processes.

4.2.2. Work climate dimension:

In this dimension (Table 2), assessed using a scale of 1 to 5, a mean of 4.27 is identified as the highest, corresponding to the variable “work rules are applied objectively”, showing PRPs recognize rules are applied equally to them and to other employees. Likewise, the variables “possibilities of making friends within my work team” and “respect for difference” have a mean of 4.21 and 4.24, respectively. In this connection, and as described in the theoretical framework, some variables that influence work climate are linked to cooperation, interpersonal relationships, and motivation - variables that were rated well by the PRPs surveyed. Concerning the deviation, two high values are identified for the variable “level of participation in the company’s cultural and recreational activities” and the variable “colleagues are aware of my reinserted-person status” which were 1.249 and 1.237, respectively. This shows the data are very dispersed with respect to the mean of each of these variables.

Table 2 Work climate

| Variable | N° | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Support received from the boss or superiors | 71 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 4.08 | 1.011 |

| I establish trusting relationships with my colleagues | 71 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 4.14 | 0.930 |

| Possibilities of making friends within my work team | 71 | 2.0 | 5.0 | 4.21 | 0.860 |

| Level of participation in the company’s cultural and recreational activities | 71 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 3.59 | 1.249 |

| Opinions, ideas, and proposals are taken into account | 71 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 4.01 | 1.021 |

| Work rules are applied objectively | 71 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 4.27 | 0.940 |

| Work flexibility regarding personal matters | 71 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 4.04 | 1.088 |

| Respect for difference | 71 | 2.0 | 5.0 | 4.24 | 0.746 |

| Colleagues are aware of my reinserted-person status | 71 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 1.69 | 1.237 |

Source: Authors’ own elaboration.

It should be clarified that the variable “my colleagues are aware of my reinserted-person status” is associated with the information that other company employees have about them. Thus, the survey results show that, in most of the cases, colleagues of the surveyed PRPs are not aware of their status; as a result, the mean of this variable is the lowest at 1.69.

Work satisfaction dimension. Based on a Likert scale from 1 to 5, the mean of the variable “work creates positive changes in my personal life” is 4.45, and a standard deviation of 0.693 means the responses represent the entire surveyed group.

The result is similar and positive as six of the nine variables are rated with a score higher than 4. As such, and as discussed in the theoretical framework, satisfaction is a positive attitude that a person experiences when performing work that generates motivation and satisfaction to fulfil their duties adequately, as evinced in the results obtained for most of the variables in this dimension (Table 3). The variables “ease of job promotion” and “the company meets my financial interests” are identified as the variables rated below 4, with a mean of 3.17 and 3.62, respectively. This indicates PRPs believe companies’ efforts to generate total satisfaction in terms of finances and career growth within them are still insufficient.

Table 3 Work Satisfaction

| Variable | N° | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The company meets my financial interests | 71 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 3.62 | 1.061 |

| Opportunities for continuing education | 71 | 2.0 | 5.0 | 4.13 | 0.877 |

| Ease of job promotion | 71 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 3.17 | 1.383 |

| I received information about my work duties | 71 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 4.25 | 0.906 |

| I feel committed to the company | 71 | 2.0 | 5.0 | 4.23 | 0.959 |

| The company fosters my reintegration process | 71 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 4.15 | 1.117 |

| I feel that the processes employed to monitor my duties are the same as for the rest of my colleagues | 71 | 2.0 | 5.0 | 4.15 | 0.936 |

| I can tell there is a work overload due to my special status | 71 | 1.0 | 5,0 | 2.86 | 1.437 |

| Work creates positive changes in my personal life | 71 | 2.0 | 5,0 | 4.45 | 0.693 |

Source: Authors’ own elaboration.

Experiences and senses of work dimension.Table 4 shows a mean higher than 4.00 in eight out of the nine variables, with the variable “work has changed the meaning of the value of life” being the highest with a mean of 4.46. Moreover, the variables “work has allowed me to develop skills and abilities”, “work has helped me be recognized as a citizen”, “work has facilitated access to health services”, and “work has strengthened my family and social relationships” also obtained a representative mean above 4.15, from which PRPs’ high work satisfaction relating to experiences and sense of work can be inferred.

Table 4 Experiences and sense of work

| Variables | N° | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| My appreciation for institutions has changed | 71 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 3.82 | 1.187 |

| I have learnt about new strategies for conflict resolution | 71 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 4.07 | 1.019 |

| Work has strengthened my family and social relationships | 71 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 4.15 | 1.009 |

| Work has allowed me to acknowledge my rights and obligations | 71 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 4.20 | 1.077 |

| Work has facilitated access to health services | 71 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 4.24 | 0.992 |

| Work has allowed me to develop skills and abilities | 71 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 4.21 | 0.877 |

| Non-formal education contributes to and fosters the professional training process | 71 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 4.11 | 0.934 |

| Work has helped me be recognized as a citizen | 71 | 2.0 | 5.0 | 4.30 | 0.835 |

| Work has changed the meaning of the value of life | 71 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 4.46 | 0.842 |

Source: Authors’ own creation based on SPSS results.

In this light, and as discussed in the theoretical framework, employment generates social integration and is one of the ways of life learning in society. The results obtained in this dimension confirm so: means higher or very close to 4 were obtained for all the variables in terms of satisfaction linked to experiences at work and the sense assigned to it.

4.3. Mixed analysis of the information

In the qualitative dimensions pertaining to sustainable labor inclusion, fair recruitment, and the treatment managers discuss, there are awareness workshops, ongoing communication with employees, an atmosphere of trust, psychosocial support, diversity management, and fair pay and treatment in terms of responsibilities and commitments. This is evidenced in highly rated scores (above the mean) assigned by the employees to work climate dimension variables, such as “work rules are applied objectively”, “interpersonal relationships”, “support received from the boss and superiors”, “opinions, ideas, and proposals are taken into account”, and “respect for difference”. Employees also provided high scores in the work satisfaction dimension, where the following items stood out: “opportunities for continuous education”, “I received information about my work duties”, “I feel committed to the company”, and “I feel that the processes employed to monitor my duties are the same as for the rest of my colleagues.” As for the experiences and sense of work dimension, employees gave the following variables scores that are highly correlated with organizational policies: “work has allowed me to acknowledge my rights and obligations”, “work has facilitated access to health services”, and “work has enabled me to develop skills and abilities”.

However, in the work satisfaction, and experiences and sense of work dimensions, a negative score which is contrary to organizational dimensions is observed: fair recruitment, treatment and administrative tools, and responses given by managers in the interview. A high percentage of the workers surveyed gave very low scores to the variables “colleagues are aware of my reinserted-person status”, “I can tell there is a work overload due to my special status”, “ease of job promotion”, and “the company meets my financial interests”. This means that although labor inclusion programs have been developed and have allowed increasingly more people to be able to reintegrate into civilian life through an employment relationship with an organization, there are still gaps associated with discrimination in terms of salaries, promotions, work overload, and lack of information by all members in the company regarding these workers’ reinserted-person status. The researchers may infer companies still fear the work environment will deteriorate with the presence of these ex-combatants. This contradicts the work carried out by the ARN in matters of education, assistance, and monitoring of PRPs, and the permanent support to companies linked to the reintegration program to enable organizations to rethink their hiring policies and devise new processes that provide more options to this population, removing the stigma or label that they carry for having belonged to a group outside the law.

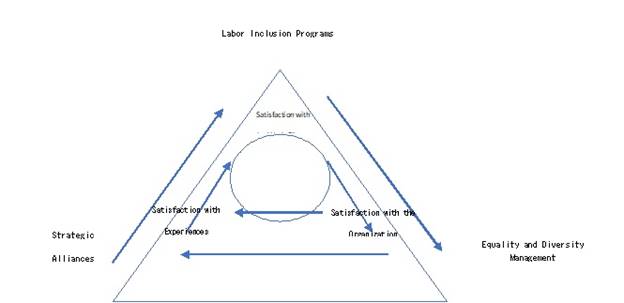

Figure 1 shows the labor inclusion process from the State, the companies, and the ex-combatant workers’ perspective.

5. Conclusions

The reincorporation of demobilized individuals into civilian life has created important changes, not only from the political sphere, but also from the economic and social spheres, which leads to more actors joining the process with the aim of bringing the inclusion of individuals in reintegration processes to civilian life to a successful conclusion.

This research made it possible to show the ARN is one of the main actors in the reintegration process -it manages, implements, coordinates, and evaluates the reintegration and normalization programs of the demobilized. Nevertheless, despite the good work carried out by the ARN, it is necessary to strengthen the legislation by which social, tax, or economic benefits are granted so that companies can employ PPRs voluntarily and without the need for the Agency’s intervention.

With respect to effectiveness in the labor inclusion of PRPs, it can be concluded that it is evaluated differently according to the company: one of the companies measures it based on staff retention and the disciplinary processes that it must conduct with individuals. Conversely, another company measures this indicator by the number of people who are or have been part of the program; and finally, a third one measures it by staff turnover and employees’ loyalty in times of crisis in the company. This is an indicator of great importance in the process because it can show whether the labor inclusion model works. Accordingly, the need to create a standard instrument for companies -or at least one with several well-defined common topics- which helps to identify the impact generated by the implementation and the development of the model to secure improvements for a successful reincorporation is identified.

Lastly, in relation to equal treatment, not labelling PRPs is a cross-cutting theme in the companies under study. The aim is to create an environment of trust that will enable individuals to start to heal their past and strengthen personal growth, leading them to successfully joining civilian life. In this paradigm-abandoning stage, companies choose not to disclose individuals’ past -that is, their origin-, and allow them to decide whether to do so themselves because of social interaction processes.

Although employed ex-combatants assign a high score to the work environment, the established interpersonal relationships, and the support received by superiors in the companies where they are undergoing their reintegration process, dissatisfaction with remuneration schemes, promotion, and work overload persists. This shows companies and their managers must work hard to improve the process and undergo much more training on inclusion issues and the importance that work holds -within the framework of the personal and social spheres- in the lives of individuals in the reintegration process.

The results obtained in this research allow us to define some strategies that companies should adopt for the labor inclusion process of PRPs:

Companies must be an active part of the Peace Agreements with demobilized groups and align their human management areas to post-conflict needs.

Organizations must have competent personnel to lead psychosocial inclusion actions and design support strategies that facilitate an understanding of the context and reality of PPRs.

Organizations must build trust-based internalization processes to see PPR hiring as an opportunity for the company rather than a threat, leading to overcoming vulnerabilities and developing PPRs’ skills that can be applied in the organization.

Company managers must understand labor inclusion of PRPs is a matter that goes beyond regulations and which should be a fundamental educational instrument for both peace and country building. In this sense, the challenge is expanding their social responsibilities towards human development.

It is recommended future research includes a broader population of persons in the reintegration procress as well as companies working with this inclusion model. This will make it possible to find further elements of judgement and generate broader discussions among all actors (public, private sectors, unions, academia, and society at large) in the interest of contributing to the sustainable development of the country.