1. introduction

According to Samuelson and Nordhaus (1996, p. 4), economics is “the study of how societies use scarce resources to produce valuable commodities and distribute them among different people.” Coraggio (2011, p. 286)defines Economics as “a system of norms, values, institutions, and practices that arise historically in a community or society to mediate the human beings-nature metabolism through interdependent production, distribution, and circulation activities and the consumption of adequate satisfiers to address the legitimate needs and desires of all, defining and mobilizing resources and capabilities to achieve insertion into the global division of labor, all in order to amply reproduce (Live Well) its members’ lives, activities and futures, and territory”.

The neoclassical development of economics that prioritizes the search for profit through mercantile relations has led humanity to a crisis of sustainability, which nowadays even threatens its survival and that of nature itself. Natural resources are being sacrificed by prioritizing market demands through wasteful human consumption, jeopardizing availability for future generations. Hinkelammert and Mora (2009, p. 44) asserts, “we are no longer fundamentally facing a dichotomy between capitalism and socialism or between capital and labor, but rather a dichotomy between total market and human survival.”

Given the above, Albán Moreno (2008) asserts that in the face of insufficient State and market responses to magnified issues such as poverty and growing impoverishment, unemployment and underemployment, different local communities’ socioeconomic deterioration, alternative economic forms such as the popular economy, cooperativism, ecological economy, local development, etc. come to light. These are framed in the Social and Solidarity Economy (SSE).

Jean-Louis Laville, based on Mauss and Polanyi’s theoretical foundations, enables the design of a specific “alter-economies” path, the prospect of Solidarity Economy, which “refers to a conception of change where actors fall in a democratic framework for the evolution of power relations so that the plurality of institution or social inscription modes in the economy can fully acquire citizenship rights” (Laville, 2004, p. 10). Such an outlook attests to the free market and the State’s inability to guarantee human needs’ satisfaction, which leads society, organized through new social structures, to think of scenarios capable of guaranteeing each citizen’s actual rights and duties, thus embracing the principles that enable organizations’ social, economic and environmental sustainability.

On the other hand, The Circular Economy (CE) arises as an alternative to the linear economy that holds a “take, make and discard” approach and is based on the exploitation of large quantities of cheap and easily accessible materials and energies, recording unprecedented levels of growth that jeopardize future generations’ resources. EC is poised as “restorative and regenerative on purpose.” Such a new model seeks to dissociate itself from the global linear economic model and entails challenges such as creating employment and reducing environmental impacts, including carbon emission, thus advocating for a new systems thinking-based economic model under unprecedented favorable conjunction of technological and social actors (Ellen Macarthur Foundation [EMF], 2015).

The ultimate goal of the CE model is to set up an economic system where industrialization takes place under the umbrella of sustainability and a diminished environmental footprint. “The leitmotif of the circular economy is to make the most of resources used and minimize the generation of unusable waste” (Marcet, Marcet, and Vergés, 2018, p. 11)

Villalba Eguiluz, González-Jamett, and Sahakian (2020) explore those two concepts and recognize that it is possible to identify some SSE and CE complementarities. Both appear as alternatives to the capitalist model, and while the SSE places people and people’s needs at its center, the EC entails a model that seeks to reduce, lengthen and close natural resources exploitation cycles, projecting greater environmental sustainability. However, while the first concept has been in the builds since the 19th century, the second is more recent (21st century). Thus, the following question is posited:

What are the conceptual contributions of the Social and Solidarity Economies (“SSE”) to the Circular Economy (“EC”)?

The theoretical framework will address the theoretical and conceptual exploration of the SSE and the CE to answer that question. Later on in the discussion and conclusions, there will be some comparative analyses of our own and some authors’, which afford an answer to the question and elements of convergence for the two economic approaches, as well as for future research.

2.Theoretical framework

2.1. Conceptual aspects of social and solidarity economy (SSE)

2.1.1. Background.

According to Bidet (2010), The Social and Solidarity Economy (SSE) has been in evolution for almost 200 years, eliciting discussions at the social, political, and economic level, giving its earliest glimpses in Europe since 1830. The SSE regained strength during the 80s and created two theoretical strands with internal variants: the European and the Latin American. The first one emphasizes cooperativism and the Social Economy, while the second one parts from alternative economic experiences, based on the Solidarity Economy (Guerra, 2004, p. 2)

There are different aspects and definitions in Latin America: Mance (2008) refers to “Solidarity in Collaboration” to work solidly together, under a moral sense of joint responsibility, for the wellbeing of everyone in particular. Hinkelammert and Mora (2009) speaks of a critical theory of reproductive rationality, which enables the scientific, not the tautological, evaluation of the market system and leads an economic practice in conjunction with the conditions that enable reproduction of human life and, therefore, of nature. From that perspective, economics need to re-evolve towards the “Economy of Life.”Razeto (1999) speaks of the “Solidarity Economy “ based on incorporating solidarity into both economic theory and practice, starting by “producing with solidarity, distributing with solidarity, consuming with solidarity and accumulating and developing with solidarity,” to such an extent that “it gets to transform the economy structurally from within, generating new and true balances,” thereby creating new economic rationality. Coraggio (2011) accounts for a more radical outlook through “Labor Economics” because, according to the author, it “carries the greatest potential to organize theoretical thought to organize research and the design of strategies in the face of the Capital Economics and the Public Economics theories” (pág. 56).

2.1.2. Concerning Social and Solidarity Economy (SSE).

Laville (2010) differentiates between the Social Economy and the Solidarity Economy, where the former is third sector-related, bringing together collective organizations based on mutual aid and citizen participation in cooperatives, while the latter is poised as a broad movement where SOLIDARITY is cross-sectional. Pérez-Mendiguren and Etxezarreta (2015) split SSE by stating that it is born from the mixture of two akin and related concepts, which differ in terms of the social context where they arise.

2.1.2.1. The Social Economy.

The Social Economy was born in the 19th century and has become renowned in Europe given its Institutional and legal framework and ethical and regulatory complement, as it is reckoned as “a different way of doing business.” It is characterized by: 1. Placing human beings above capital (both in decision-making and in managing surpluses), 2. Management autonomy and democracy, 3. Solidarity (internal and external) and 4. Prioritized servicing of members and the community. It includes community involvement organizations through associations and the cooperative movement (cooperatives, mutuals, and associations) (Pérez-Mendiguren and Etxezarreta Etxarri, 2015).

Per Bidet (2010), the Social Economy sector comprises both “public sector” organizations and the capitalist companies making up the “private sector.” Some countries, such as the United States, use the term “Third Way,” whereas some Asian countries employ the “non-profit sector” (Figure 1). According to Defourny and Nyssens (2012), the concept of “social enterprise” appeared in Europe in 1990 at the heart of the third sector, and it brings together cooperatives, associations, and mutuals according to European tradition, and foundations ever more or, in other words, all private, not-for-profit organizations, which engage in commercial and productive activities that feed (finance) their social purpose.

The notion of “social enterprise” does not compete with that of “social economy” since Defourny and Nyssens (2012) assert that although there are several schools of thought, both recognize organizations that align with the literature on the third sector (social economy), primarily when focused on community development, in addition to sharing economic and social principles and dimensions.

On the other hand, for Bouchard, Cruz Filho, and Zerdani (2015), in Québec, the institutional definition does not contemplate private foundations or other non-profit organizations that do not follow cooperative guiding principles.

Based on the scientific, political, and institutional consensus of various actors across Europe, the Social Economy is defined as:

“The set of formally organized private companies, with autonomy in decision-making and freedom of adhesion, created to satisfy the needs of their partners through the market by producing goods and services, ensuring or financing and where the eventual distribution of profits or surpluses among the partners, as well as decision-making, are not directly linked to the capital or contributions made by each partner, with one vote belonging to each of them. The Social Economy also groups together those formally organized private entities with autonomy in decision-making and freedom of adherence that produce non-market services in favor of families and whose surpluses, if any, cannot be appropriated by the economic agents that create, control or finance them” (Chaves and Monzón, 2018; Villalba Eguiluz et al., 2020).

2.1.2.2. The Solidarity Economy.

According to Chaves and Monzón (2018, p. 34), the notion of a Solidarity Economy developed in France from the 1980s, based on four core ideas: 1. The hybridization of economic resources was emphasized, including market, non-market, monetary, and non-monetary resources, 2. It focused on the participatory political element and the democratization of economic decisions. 3. Its significance in the face of statutory forms, it projected to become a transformative alternative proposal to neoliberal globalization, and 4. The will to meet new social needs innovatively, with multiple actors and an explicit desire for social change.

The Solidarity Economy comprises a heterogeneous set of theoretical approaches, socioeconomic realities, and business practices. It builds production, distribution, consumption, and financing relationships based on justice, cooperation, reciprocity, and mutual aid principles. This movement is formally broader in terms of types of organizations and comprises processes at the macro (self-managed companies sector) and micro levels (smaller-scale associative companies) (Pérez-Mendiguren and Etxezarreta Etxarri, 2015; Arango Jaramillo, 2005).

It is defined through two dimensions: The Economic Dimension with two different meanings of economics: the formal meaning concerned with “the process of economizing scarce resources,” and the second meaning referring to the “satisfaction of needs through social interactions between human beings and nature” (Polanyi, 1977, cited by Laville, 2010). This dimension accounts for three economic principles: 1. The market, 2. Redistribution and 3. Reciprocity. The nineteenth-century Political Dimension defined solidarity associations as “the first line of defense,” that is, civil society made the first approaches to the search for the common welfare before the State took on their development (Lewis, 1997, cited by Laville, 2010).

The Solidarity Economy insists on the principle of solidarity and the close relationship between associative action and the authorities, for a historical analysis identified that associative organizations “are not only producers of goods and services since they possess political and social interference factors of relevance” (Seibel, 1990, cited by Laville, 2010). The term “Solidarity” must be associated with the economy as a human activity; in general terms, “it seeks to satisfy society’s needs for the provision and consumption of goods and services, which presupposes the rational use of resources.” (Albán Moreno, 2008, p. 30)

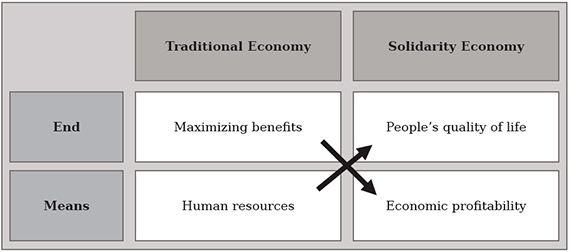

The Solidarity Economy, in contrast with the classic Social Economy, possesses three distinctive characteristics: 1. The social demands that it tries to meet, oriented towards social goods instead of the market, 2. The actors behind it, and the explicit desire for social change (Chaves and Monzón, 2018; Villalba Eguiluz et al., 2020). Askunze (2007) argues that it is an alternative consideration to the current neoliberal and conventional economy’s priority system since it vindicates the economy as a means, not an end, at the service of personal and community development (Figure 2).

2.1.2.3. The Social and Solidarity Economy.

For Moreau, Sahakian, Van Griethuysen, and Vuille (2017), the Social and Solidarity Economy (SSE)configures itself in a social movement and an existing practice, which arises in response to a series of growing socioeconomic problems: recurring financial crises, the welfare state’s failure to address social problems such as increased inequality and create sustainable ways of production and consumption. The SSE includes various economic initiatives ranging from new social relationships like fair trade programs and new currencies such as community currencies.

Pérez-Mendiguren and Etxezarreta (2015) state that the SSE is construed as a whole in the theoretical body of Latin American and European concepts, which comprises the economic process and seeks to ensure people’s livelihoods and democratize the economy. Its multidimensional nature includes at least three dimensions: 1. Theoretical: deals with building an alternative paradigm on the economy, compared to the conventional paradigm, 2. Political: social transformation towards an alternative socioeconomic model, 3. Business: based on democracy, self-management, and collective entrepreneurship.

The SSE establishes a reciprocity-linked third sector within the framework of the plural economy. Diverse authors agree that the SSE fits with Polanyi’s idea of a “substantive economy embedded, rooted, grounded in society and its institutions.” Among the distinctive features of the SSE is “its transformative potential to build another economy,” as mediated by the degree of coherence between its organizational and institutional practices and the alternative values and principles this approach sustains (Laville, 2010; Villalba Eguiluz et al., 2020).

2.1.3. Principles, Facets, and Challenges of the Social and Solidarity Economy.

The Solidarity Economy regards people, the environment, and sustainable development RIPESS (cited by Villalba Eguiluz et al., 2020) defines the SSE as an “alternative to capitalism and authoritarian State-controlled economic systems,” and underlines the following values: “humanism, democracy, solidarity, inclusivity, subsidiarity, diversity, creativity, sustainable development, equality, equity and justice, respect and integration between countries and peoples, a plural and supportive economy.”

The above values are intertwined with institutional agreements or “principles” to drive the fulfillment of the SSE philosophy. Thus, organizations create them as a reference for organizations that fall in this sector. REAS (“Network of Alternative and Solidarity Economy Networks”) published the “Charter of Principles of the Solidarity Economy” (2011) in May 2011, the relevant features of which are highlighted below:

Equity Principle: it allows recognizing all people as subjects of equal dignity and protects their right not to submit any domination-based relationships regardless of condition (social, gender, age, ethnicity, etc.).

Work Principle: Key to human beings, the community’s quality of life, and the economic relations between citizens, peoples, and States.

Environmental Sustainability Principle: All human beings’ productive and economic activities become intertwined with nature; thus, it is paramount to seal an alliance with it, based on recognizing its rights.

Cooperation Principle: Promotes learning and cooperative work between people and organizations through collaborative processes, joint decision-making, shared responsibility and duties, guaranteeing maximum horizontality while respecting autonomy at the same time.

“Non-Profit” Principle: It seeks to build a more humane, supportive, and equitable social model and measures economic balances, as well as human, social, environmental, cultural, and participatory aspects, in order to achieve a comprehensive, collective development through efficient management os resources.

Environmental Commitment Principle: The environmental commitment comes in the form of participation in the territory’s sustainable local and community development, insofar as it entails integration, involvement in networks, and cooperation with the social and economic fabric.

SSE organizations are placed in varying sectors of the economy; hence, these principles are context-dependent. Coraggio (2011) makes the grouping below around five categories: 1. Production-related: recognizes work, access to knowledge and means of production, solidarity cooperation, and socially responsible production. 2. Distribution-related: projects justice and joint reproduction and development assurances, equitable distribution per work performed and contribution of resources, non-exploitation of others’ work and non-discrimination, 3. Circulation-related: Encompasses Self-sufficiency (autarky), Reciprocity, Redistribution, Exchange, Planning, and currency usury-free. 4. Consumption-related: Responsible, supportive, healthy consumption variants in balance with nature, and favors users’ access and self-management regarding collective livelihoods. And the remaining five. Cross-cutting principles: free initiative and socially responsible innovation, Pluralism/ diversity, complexity, and territoriality fall.

Coraggio (2011) proposes these three elements as a society transformative experimental framework: 1. Practices: include formal and non-formal associative ventures, 2. Criteria: Self-managed work measurement units, and 3. Senses: adduce the rules to ensure good living. This framework contains varying organizations with different initiatives and forms of organization that have grown under a NETWORK structure from the local to the global (Askunze Elizaga, 2007).

Askunze (2007) makes the following classification by facets: 1. Production and Solidarity Companies: Solidarity or Insertion Companies 2. Alternative Financing and Ethical Banking: rescue the social value of money by putting it at the service of community transformation and development. Solidarity financing, responsible saving and investment, alternative exchange formulas or social currencies, and ethical consultancies for specialized support fall therein. 3. Fair-trade, Solidarity Economy markets and Responsible Consumption: settings that advocate for rethinking trade relations, including fair trade, Solidarity Economy markets, and responsible consumption. 4. Citizen participation and education for social change: These allow enhancing citizens’ power consciously and with values for s social change.

Sahakian (2016) poses two significant challenges for the SSE: On the one hand, the forms of relation with the dominant market and the State, given the tensions arising from the systemic transformation bets, as due to accentuating the “alternative,” “anti-capitalist” and “radically democratizing” nature; on the other hand, is the issue of scale and the difficulties in scaling-up local innovations. Faced with that, Villalba Eguiluz et al. (2020) verified that most SSE activities are micro, local, and arise from experiences at the territorial level; hence exponential growth appears as a warning as it jeopardized the solidarity philosophy, affecting the fulfillment of the social function on account of the interference due to size.

2.2. Conceptual aspects to the Circular Economy (CE)

2.2.1. Background.

The concept of Circular Economy (CE) emerged from the physical sciences, from Georgescu-Roegen’s studies on the relationship between economic activities and the natural environment; based on biophysics and, in particular, the second law of thermodynamics and the law of entropy, restrictions are imposed on economic activities (Moreau et al., 2017). According to Cerdá and Khalilova (2016), it comes from the early 1990s industrial ecology studies and includes thoughts from functional service economics or performance economics. This concept took hold after the USA Ellen MacArthur Foundation published government- and business-supporting documents in 2012 to promote CE as a way to integrate environmental and social sustainability into economic development.

For Chaves and Monzón (2018), the global political, economic, and scientific scenes have suffered interruptions in the last fifteen years due to a series of terms that have made clear the delegitimization of the prevailing economic model based on the capitalist enterprise. This way, a new lexicon arises from the latest crisis in the context of the structural transformation of Western economies, new concepts taking force, including “the Solidarity Economy and alternative economic practices,” as well as the “Circular Economy.” The latter, according to the authors, has installed itself in the academic and political worlds in recent years, focusing on sustainable development together with other terms such as “green economy,” “ecological economy,” “functional economy,” “Resource-based economy” and “blue economy.”

Ruíz et al. (2018) found in 2018 that 54.69% of 1920 references dealt with CE and that such growing academic interest in CE was because “it arises as a response to two severe environmental issues that are on their way to becoming a civilization problem: The first is the depletion of raw materials due to massive extraction, and the second is the impossibility of managing the waste generated under the linear model.

2.2.2. On the Concept of Circular Economy.

Per the EMF (2015), CE is an economy that is “restorative and regenerative on purpose,” a model that is unlinked from global economic development, from the consumption of finite resources. Three significant contributions emerge at the companies and economies level regarding the generation of growth: The creation of jobs, the reduction of the ecological footprint in the economy (which includes the emission of greenhouse effect gases and degradation of the planet), and the reduction of the cost of living and management in public institutions (EMF, 2015, JLP, 2016)

The EC model is to replace a “linear economy” based on the extraction of natural resources and raw materials (get), Production of Goods and Services (make/do), consumption (use), and waste generation (throw away), which ultimately impact the environment negatively. The EC proposes both converting wastes into new resources, as well as an innovative change to the production system, according to which the idea of regeneration would drive the design of each phase in the production process. Ultimately, it seeks to close loops in industrial ecosystems and minimize waste, implying that resources and products would maintain their value by becoming reusable through renewable energy and product design (Cerdá and Khalilova, 2016; Chaves and Monzón, 2018).

Several European countries have institutionalized the CE through the European Commission, the European Economic and Social Committee, and the Committee of the Regions (Chaves and Monzón, 2018); it has even had some influence in China (Cerdá and Khalilova, 2016). The French Environment and Energy Management Agency issued the following definition: the EC is “an economic system based on exchange and production that, at all stages of the product or service life cycle, aims to increase efficiency in the use of resources and reduce the impact on the environment, while pursuing people’s wellbeing” (Geldron, 2013, 4 cited by Moreau et al., 2017)

In Colombia, the “Ministerio de Medio Ambiente y Desarrollo Sostenible” [Minambiente] (Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development) and the “Ministerio de Comercio, Industria y Turismo” [Mincomercio] (Ministry of Commerce, Industry, and Tourism), have proposed the following: “the main differentiating contribution of the circular economy is its systemic and holistic nature; it focuses on optimizing a system by taking into account all its components. The definition intends a productive system that self-restores and self-generates due to its interconnected and intelligent design, as occurs in nature where from one organism’s residue is the raw material for another, where there are symbiotic relationships between species, such as the carbon or nitrogen cycle, for instance.” (2019, p. 20). The DANE regards the EC as a production and consumption system that promotes the efficient use of materials, water, and energy, taking into account the ecosystems’ ability for recovery and the circular use of material flow through the implementation of technological innovations, alliances, and collaboration between actors, and the promotion of sustainable development-based business models (Dane, 2020, p. 7)

2.2.3. Circular Economy principles, characteristics, and critical aspects.

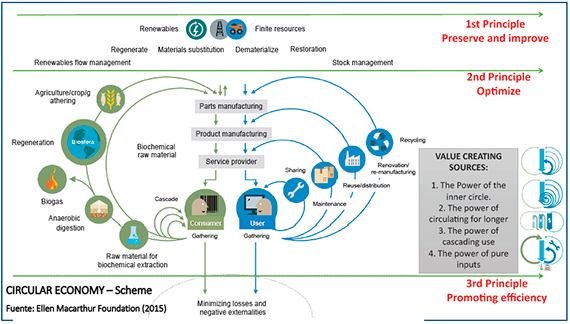

In order to substantiate the EC, the EMF (2015, p. 7) proposes three principles: 1. “Preserve and enhance natural capital by controlling finite reserves and balancing the flow of renewable resources,” related to regeneration; 2. “Optimize the yields of resources by distributing products, components, and materials through their maximum utility at all times in both technical and biological cycles,” thus embracing circularity and natural recomposition; and 3. “Promote system efficiency by detecting and eliminating negative external factors from the design,” which points to innovation in product eco-design.

There are two types of cycles to the CE (EMF, 2015): the technical cycle that manages and recovers technical and finite materials, where use replaces consumption, and the biological cycle concerned with renewable materials (biological) nutrients regeneration flows; consumption only occurs here. Thus, the CE has set some value creation cycles, which are the key to redesign production processes under a circular approach. According to EMF (2015, p9) the following is found:

“1. The power of the inner circle refers to the idea of repairing and maintaining a product while preserving most of its value. Here, the narrower the circle, the more valuable the strategy; 2. The power of circulating for longer refers to prolonging the product’s life span, either for a longer time or to last more cycles. An optimal life span must observe the improvement of energy performance over time; 3. The power of cascading use refers to diversified reuse throughout the value chain; that is, an already-consumed product serves as raw material for other products, replacing virgin materials. 4. The power of pure inputs lies in the fact that the flows of uncontaminated materials increase efficiency in collection and redistribution, maintaining the quality of technical materials especially” (Figure 3 to understand the dynamics).

Source: Author’s own elaboration based on the Ellen MacArthur Foundation (2015).

Figure 3 Circular economy diagram and value creation sources

Regarding the technical, economic, and social instrumental factors necessary to ensure an appropriate and prompt transition to a circular economy, Cerdá and Khalilova (2016, p. 12) sustain the following:

Innovative Business Models consisting of various facets such as product-,use- or result-oriented product-service systems that jointly satisfy the consumer, a second life span for materials and products through recovery and reconditioning, design-based product transformation coupled with the certain materials’ ability to be reworked, Recycling 2.0 (that includes innovation in high-quality production technologies), and collaborative consumption in pursuit of the satisfaction of actual and potential needs.

Eco-design and design for sustainability: A methodology that considers actions aimed at product or service environmental improvement during the life cycle.

Extending products’ useful life through reuse, repair, update, rework, and remarketing. Reuse conserves physical assets, raw materials, and energy used.

Waste prevention program: the EC has disseminated the 3Rs proposals (reduce, reuse, recycle) or the 9Rs, which Villalba Eguiluz (2020, p. 10), based on an adaptation of Potting et al., 2017 and the Basque Circular Economy Strategy, groups as follows: Use of smarter product manufacturing (Reject, Rethink and Reduce), extending the product and its components’ useful life (Reuse, Repair, Renew and Remanufacture), and harnessing of materials (Recycle and Recover). These blocks allow following a hierarchy regarding the positive impact and ability to drive circularity.

Marcet et al. (2018) have addressed the “integral sustainability of territories,” a bet on more efficient sustainable models being arranged through indicators and public policies designed to harness waste management, urban and architectural design, and energy management by creating environmental, fiscal, and economic innovation instruments.

Of the above typologies Minambiente, Mincomercio (2019) recognize as keys the waste valuation models, the introduction of circular models with reused materials, as well as designing models that enabled extended products and services useful life from production and through shared use as mediated through resource use optimizing technologies.

Regarding critical CE aspects, although it supports the three dimensions of sustainable environmental, social, and economic development (Villalba Eguiluz et al., 2020), it needs to overcome a complex linear system cultural aspect, which is grounded in the fact that “selling more implies more profits.” Thus, business strategies have sought to hike profits through increased sales, low costs, and making old products obsolete. In light thereof, the circular model is challenged with breaking a cultural paradigm, where products must be a part of the integrated and focused business model that demands the presence of actors that change operating patterns, through either new guidelines and legal frameworks or voluntariness, understanding the importance of environmental sustainability as a determinant of business sustainability.

3. Discussion and conclusions

The conceptual and theoretical exploration above found that both CE and SSE are attempting to drive today’s production and consumption systems towards a more systemic approach: the former by integrating ecological principles, and the latter by prioritizing the most equitable social relations. In this vein, Chaves and Monzón (2018) hold CE and SSE as “notions attached to central crisis areas and the transformation of the system,” where the CE addresses systemic transformations in the environment not referring to a new institutional form (for these are transversal to the public, traditional private and third-sector), but to a new micro and macro approach for facing significant systemic challenges. Therefore, these are not regarded as rival but complementary concepts since they enable a better apprehension of these grand areas of change, as well as placing the role that the SSE can play therein.

From Polanyi’s point of view, the SSE has the power to understand the economic, social, and political dimension at the society level in order to find balanced forms of satisfaction for human needs grounded in an alternative discourse to that of competitiveness and the obligation to profitability demanded in the conventional, capitalist and linear economy. The SSE and the CE coming together may be achieved through two strategies for conversion: a public-institutions top-down outlook towards agents and a bottom-up one where the socioeconomic actors themselves develop social-level experiences by weaving networks and shared interests. Hence, it is necessary to identify four barriers able to limit the promotion of CE: 1. Cultural and social; 2. Regulatory and institutional; 3. Market, economic and financial; and 4. Technological (Villalba Eguiluz et al., 2020, Moreau et al., 2017).

It is essential to note that the CE is subject to a series of limitations that the ESS might complement. As such, for instance, the various CE strategies lack certain aspects of relevance: On the one hand, a comprehensive outlook of the biophysical dimensions and, on the other, the inclusion of the social, political, and institutional dimensions necessary to achieve meaningful, productive transformation (Moreau et al., 2017, Villalba Eguiluz, 2020). This way, the critical capacity of the SSE makes it possible to search for complementary elements for its improvement.

Inclusion of the social dimension: Sustainable development seeks a total balance, and the EC ignores social equity. This is inconsistent with environmental sustainability, decent work, social inclusion, and the eradication of poverty.

Broadening towards a territorial-approach holistic, systemic change: Change is not possible in small partial actions or segments of the value chain; it requires a territorial approach that allows generating symbiosis between companies, the environment, and territories.

Implementation of a political approach: hegemonic CE discourses follow the expansion of capital and maintain consumerism. That needs re-politicizing through questioning means of production ownership, democracy, for what, who, for whom, and how technology and innovation are geared beyond a technocracy.

Eco-efficiency as a supply and consumption business model: Eco-efficiency without sufficiency leads to rebound effects capable of increasing global consumption. The focus cannot only be placed on supply and producers; it must acknowledge the demand. Consumption under an extractivist approach must be overcome as the engine of development, which does not allow a harmonious man-nature relationship.

Changing the notion of CE as an alternative discourse to growth and not alternative growth itself: CE tends to operate around the neoclassical economic framework, failing to confront its basic assumptions, leading it to contradiction and conflict in the face of biophysical circularity, which is impossible to change if the economic paradigm goes unchanged.

Recognition of more efficient EC indicators: Measuring recycling encourages managers to recover high quantities of materials, which construes an actual failure as that ignores the most efficient “Rs” (such as “Reject or Reduce”), which actually prevent unnecessary consumption.

The CE can set a new production and consumption paradigm in search of a sustainable and responsible economic model; however, achieving it demands setting aside the traditional economic practices based on unlimited growth. As such, the pressure on natural resources would be left unchanged, which is unsustainable, as expressed by Korhonen, Antero, and Jryi (2018), due to biophysical limitations on account of thermodynamics, and system, global physical scale, and technological innovation frontiers, and even social governance and cultural norms.

One problem in CE is the notion of “competitiveness” since it not only forces us to be profitable but more profitable than the competition. Relative profitability requires a cost shift conducive to adverse environmental impacts on renewable energy sources (including labor). The European community’s Action Plan embraces “competitiveness” (Marcet et al., 2018) to optimize resources and maximize profits, making clear its detachment from solidarity, thus leaving its social viability behind. Under that context, the SSE’s equity focus on work and governance affords CE a key element by contributing elements such as collaboration and cooperation to overcome an aggressive competitiveness-based system (Moreaut et al., 2017; Villalba Eguiluz et al., 2020).

The Basque Country and Western Switzerland case studies by Villalba Eguiluz et al. (2020) identify the overlap between the principle of environmental sustainability with that of “non-profit.” Such SSE contribution to the EC allows prioritizing social and environmental affairs above the economic and commercial and therefore facilitates meeting the objectives of circularity and the principle of cooperation through the synergy and symbiosis key to closing material cycles. The SSE sheds light on positioning an alternative discourse to that of profit through a shared focus since limiting resource use limits profitability, which becomes possible under a collective awareness and sustainability scenario, wherein the social dimension is critical for the ecological transition.

Regarding the “principle of environmental sustainability,” this is the one bearing the strongest a priori relationship with the SSE and the EC; REAS, 2011 sustains as much, for it considers that all productive and economic activities are connected to nature. The paramount need arises to integrate environmental sustainability across all actions while continuously assessing the environmental impact (the ecological footprint). Faced with business models and circular strategies, an absent principle of solidarity would entail the possibility of falling into the trap of expanding the dominant economy, wherefrom Villalba Eguiluz et al. (2020) poise moving on from the notion of “business” for that of “economic activity.” Additionally, it is crucial to ponder breaking from the anthropocentric vision of development to introduce the “good living” perspective that allows driving the notion of solidarity to liaisoning with nature, where human beings and flora and fauna are recognized as actors also making part of that environmental balance, where ecology is the support of life in society.

As a virtuous cycle, the CE will be impossible if not “local,” an approach SSE models embrace under a territorial perspective. Thus, while supra-local regulations and incentives are helpful, their implementation must be local, practical, and measurable (Marcet et al., 2018). Paralleling experiences, models, and various tools of the CE and the SSE makes it possible to encourage the design of multiple-ownership models, citizen, democratic, and local participation scenarios articulating the outlooks of both environmental sustainability and social and economic sustainability.

The SSE and CE approaches can be considered interdependent, compatible, and can work together since neither theoretically aims at economic growth, where the CE prioritizes biophysical and sustainability goals, and the SSE people and equity. Concerning possibilities of convergence, considering some elements from Villalba Eguiluz et al. (2020), we propose:

The cooperation and collaboration principle: the SSE holds it as an implicit principle coupled with reciprocity, while it may be decisive in industrial symbiosis, collaboration throughout the value chain, technological innovation and supply systems, collaborative consumption, etc., where the CE is concerned.

Territorialized Systems: Circularity should be upheld as a system’s property rather than an individual product (isolated companies). Once conceptualized thusly, collaboration is one of the fundamental principles of systemic circularity. The SSE tends to create territorial and sectoral networks and circuits, facilitating cooperation between nearby companies and agents committed to the territory, thereby overcoming the competitiveness approach.

Work Centrality: this is an SSE principle key for the EC. Labor is a non-intensive renewable resource free of fossil energy sources or capital. Various sustainable and circular activities fall within this area. It aids in the employment crisis and allows re-conceptualizing and distributing jobs (paid, unpaid and care-related).

Institutional rules and conditions in the face of profitability: The SSE affords principle like equity, which prevents the imposed transferring of costs in time and space to other places or societies, challenging private benefits, and the principle of democratic and collaborative governance, which helps incorporate the institutions and set the rules that avoid cost outsourcing. In essence, the SSE projects the common good above economic gain.

Satisfaction of needs: on the basis of Max Neef’s Human Scale, it is essential to identify the concrete, diverse, and culturally appropriate satisfiers to meet needs. The integration of CE and SSE can help identify potential areas for articulation through the collaborative economy, servitude, and de-commodification that facilitate products collective sharing, as well as creating public and/or community systems for collective self-management of human needs.

The CE and SSE approaches are not exempt from criticism and risk due to the multiple interpretations and variants inherent to the capitalist economic system, where different actors’ multiple interests uphold eco-efficiency and industrial competitiveness discourses rather than comprehensive and global sustainability. Despite the epistemological difference between both concepts on account of the SSE being regarded as a model for the economy as a whole (including redistribution by the public sector), while the CE attaches itself to an economic vision not emphasizing enough on social considerations (social inclusion and poverty reduction); SSE values and principles can be articulated with CE objectives.

Finally, the SSE can welcome and promote CE so that they project themselves as a new global economic paradigm together, where CE is strengthened by overcoming its biophysical and social limitations and projecting a cultural change, which contemplates adopting an “economy with values” (Ruiz et al. 2018) that prioritizes global environmental sustainability and the fight against inequalities and the human dimension over profit-making interests across organizational models. Progress must be an all sectors and actors’ joint effort grounded in a synergistic perspective that allows building social capital and the development of alternatives, that, for instance, facilitate and enable a comprehensive adaptation of “integral sustainability models by the territories (Marcet et al., 2018) to face global problems without relegating entrepreneurship jointly and collaborative and democratic governance systems, as well as “institutional perspectives capable of leading to more solid CE strategies in pursuit of social and environmental objectives” (Moreaut et al., 2017)