1. Introduction

This paper explores the relationship between Corporate Governance (CG) and Corporate Social Responsibility. Since both CG and Corporate Social Responsibility refer to stakeholders’ interests, they seem to be “two sides of the same coin” (Jamali, Safieddine, and Rabbath, 2008, p. 44). Indeed, they both refer to the organization’s social duties. The different kinds of Organizational Social Responsibility related to every group of stakeholders.

Before moving forward, it is necessary to explain why the Corporate Social Responsibility term is abandoned. It is a limited concept that takes non-profit organizations out and often shifts attention to subsidiary firms’ stock-bound to a parent one (Tello-Castrillón, 2018). Nevertheless, Social Responsibility is reclaimed as linked to any hierarchical human group that shares resources and, at least, one common objective. Therefore, the organization concept appears more accurately associated with Social Responsibility than the corporation or firm terms. That is why this paper uses the Organizational Social Responsibility expression, instead of the referred term taken as limited (Tello-Castrillón, 2018, p. 2), even on textual references.

Sacconi (2012) argued that CG is the organization’s commitment to stakeholders. Therefore, CG includes OSR. Since CG links the organization to society (WBSCD, 2002; Jenkins 2009), it is a part of the Social Contract (Sacconi, 2012). In the same sense, Peters, Millers, and Kusyk (2011) stated that CG binds OSR through ethical codes.

However, the CG-featuring-OSR argument is not a finished discussion. Some authors thought that OSR trespasses on the organizational level; therefore, CG is just the organizational part of the social support implied in OSR (Kangarluie and Bayazidi, 2011; Jamali et al., 2008; Sacconi, 2012). Many others authors have considered CG and OSR to be located on the same continuum of Social Responsibility (Jamali et al., 2008). In this paper, the latter is assumed. Consequently, CG refers to organizational duties focused on legal managing system and control (Jamali, Karam, Yin, and Soundararajan 2017; Kangarluie and Bayazidi, 2011) concerning internal stakeholders. Successively, OSR refers to organizational duties, focused on the voluntary support of social development for external stakeholders as a palliative to the government insufficiency (Jamali et al., 2008).

Decisional locus offers a new detail about this continuum. The Social Responsibility assumes the OSR form when it is recognized that OSR depends on the CG decision-making process (Figure 1). Nonetheless, it has not a unique dynamic. Relationships between the board of directors and OSR may vary (Sacconi, 2012). The main reason is that the revenues of the OSR expenditures are not fully visible (Chintrakarn, Jiraporn, Kim, and Kim, 2016), especially in the short run. This ambiguity comes from two kinds of agency problems. Sometimes, it results from owners’ internal struggle, the principal-vs-principal conflict, or in some occasions, from the owners-vs-CEOs’ conflict, the principal-agent conflict.

The latter is also known as the Classic Agency Problem. CEOs who face loosing control would shift OSR expenditures to increase their prestige (Chintrakarn et al., 2016). In contrast, other authors (Kangarluie and Bayazidi, 2011; Sacconi, 2012) stated that CEOs would decrease those expenditures since OSR revenues are only visible within the long run. For its part, owners are represented in the organization by the board of directors. The owners are interested in the long life of the organization. Therefore, the principal-agent conflict can be understood as chronological collide. Namely, the bracket between owners and organizations is a long-run link, so it is their planning horizon and clashes with the short-run link of the CEO.

Emergent markets, Latin American ones included, suffer both agency problems. This issue is explained by the concentration and low democratization of property and the insufficient minor owner protection (Young, Peng, Ahlstrom, Brutton, and Jiang, 2008). Those countries face the agency problem by increasing the pressures in internal competitive markets and controlling intra-organizational systems (Young et al., 2008).

To solve the ambiguity mentioned above, Arora and Dharwadkar published a research article in 2011. Their core conceptual tool is that OSR is split into two components. One part is called negative OSR and “involves reactive compliance with minimum standards [about avoiding] (…) violations of regulatory guidelines on [the] environment or equal employment opportunities, health and safety concerns, or controversial actions such as on human or employment rights” (Arora and Dharwadkar, 2011, p. 137).

The other part is called Positive OSR and “involves proactive stakeholder relationship management [through] (…) acts such as sustainable practices, commitment-based employment practices, corporate philanthropy, and effective relations with [the] local community” (Arora and Dharwadkar, 2011, p. 137). However, Arora and Dharwadkar’s binary OSR does not give remarkable relevance to the spatiality related to the organization’s range of activity. Spatiality is essential here because the geographical proximity explains part of the Multilatinas success.

Consequently, this paper deals with mechanical OSR (MOSR) and fundamental OSR (FOSR) instead. They both are directed toward sustainability. The first one means “those [organizational] facts executed to accomplish social demands (no law enforceable) that are directly attributable to the organization” (Tello-Castrillón, 2018, p. 47) and have a visible and mechanical relationship between means and ends (Tello-Castrillón, 2018, p.187). Those acts are evident in the short run, focused on organizational sustainability and seeming to be pursued by both owners and CEOs (Stein, 1989; Chintrakarn et al., 2016). On the other hand, FOSR is “focused on the social improvement at non-adjacent levels to the [organizational] sphere of action” (Tello-Castrillón, 2018, p. 46) and is formed by the seminal principles of OSR, a holistic view of society and human development (Tello-Castrillón, 2018, p. 188). FOSR goes to complete social sustainability, its visibility increases in the long run, and it seems to be more appreciated by owners than CEOs.

2. Literature review

2.1. Corporate Governance

CG is the system for controlling and managing the activities of organizational members and their interrelationships. CG aims at promoting behavior that leads to sustainability: first, organizational sustainability and, second, a societal one among organizational members. CG must be executed through a responsible attitude covering the highest possible number of stakeholders. In this system, it is necessary to remark the organizational members’ decision-making processes and political activities, both intra and inter-organizational (Tello-Castrillón, 2018, p. 191).

The CG depicts the conflict of interest between owners and CEOs. Smith (1983) stated that a manager would not drive a firm owned by others as accurately as driving his firm. Berle and Means (1991) said that managers make major decisions pursuing their interest within a current social system that might be taken as Managerial Capitalism. Generally, managers do not prioritize the owners’ interests. To solve this, Jensen and Meckling (1976) set their core on the information asymmetry and the moral hazard that support managers’ interests. These are the main arguments of the well-known Classic Agency Problem and define the CG central struggle.

It should be understood what the components of the CG are. On the one hand, the CG research has focused on three main subjects: Financial impact, Decision-making process, and Control system. On the other hand, the definitions of CG’s most essential characteristics include universal coverage, disclosures to society, adherence to the law, and focus on stakeholders. Nonetheless, those are ordinary subjects in developed countries that are not necessarily pertinent to less developed countries. Chen, Li, and Shapiro (2011) stated that the rest of the world should not uncritically replicate CG acts of the developed countries since the latter are configured by well-differentiated institutional characteristics compared to those of the formers.

The most critical characteristics may vary to configure particular CG types. That goes according to the specific aspects of every distinguishable society located in regions worldwide (Aguilera, 2009; Aguilera, Desender, and Kabbach de Castro, 2012; Jamali, Mohamad, and Hanin, 2008). Those aspects build specific environments (Aguilera, 2009; Peters, Miller, and Kusyk, 2011). Hence, three primary world CG contexts are found. The first could be called communitarian and is in north-western Europe (Aguilera et al., 2012); the organizations and the states often act coordinated (Moon, Kang, and Gond, 2010; Assländer, 2011). The second would be individualistic, settled in the USA and UK, where leadership and self-made individuals initiate most activities (Aguilera et al., 2012). However, the communitarian and individualistic CG contexts belong to developed countries and share the same characteristics of the Classic Agency Problem. In contrast, less developed countries, including Latin America, frequently have another conflict of interest: struggle between minor owners vs. major owners (Young et al., 2008; Chen, Li, and Shapiro, 2011), through so-called expropriation. This glimpses evidence for the existence of a particular Latin-American context of CG which awaits to be named.

2.2. Multilatinas

Since Latin-American countries show a particular CG context, it is possible to establish the specifically dealing issues of Latin-American firms. In brief, that context consists of highly concentrated firm ownership, powerful local families, weak stock markets, and a lack of institutional strength. Within Latin America, the most relevant firms are the so-called Multilatinas.

The Multilatinas are Latin-American multinational firms that have expanded their activities all over this region (Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe-CEPAL, 2005; Cuervo-Cazurra, 2008; Ramírez, 2015; Ramsey, Rutti, Lorenz, Barakat, and Sant’anna, 2017). The Multilatinas are usually owned by a majority-block inside a powerful local family group (Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe-CEPAL, 2005). Brazil is the primary origin of these firms, followed by, in order of importance, Mexico, Chile, Argentina, Colombia, and Venezuela (Boston Consulting Group, 2009). The expansion of Multilatinas is explained by the firms’ advantages of regional resources, lobbying abilities, and deep knowledge of Latin American consumer patterns (Price, 2012).

Nowadays, Multilatinas spread conti-nuously, attempting to become globalized. Accordingly, these organizations would hire exceptionally experienced CEOs who are highly interconnected in business networks. When hiring breaks a long tradition of organizational leading by owner’s family CEOs, it is called Professionalization (Stewart and Hitt, 2012). This Professionalization is especially relevant in managerial capitalism times (Berle and Means, 1991), where CEOs’ decisions affect thousands of people.

The Global markets demand Multilatinas to behave as socially responsible actors. Otherwise, the consumers would block the Multilatinas activities and would not purchase their goods and services. Meeting Social Responsibility requirements legitimize Multilatinas to the world. That leads to talk about OSR.

2.3. Organizational Social Responsibility

OSR is defined as organizational attitudes and actions (often beyond the law) that show an organizational mission that simultaneously contributes to the improvement and sustainability of surrounding community stakeholders and society. Improvement is made of four dimensions: legal, communitarian, competitive, and environmental. In the process, stakeholders’ interpretations of their welfare must be considered (Tello-Castrillón, 2018, p. 193).

Many authors consider OSR somewhat an instrument to gain market power (Galbreath, 2009; Galbreath, 2006; Drucker, 1984; Friedman, 1970; Porter and Kramer, 2006). Consequently, an instrumental stream is configured, which cuts the real essence of Social Responsibility: the organization’s commitment to the world, society, and sustainability. Responsibility itself means that an individual (organizations may be considered partly as individuals) carries the effects of its own decisions (Tello-Castrillón and Rodríguez-Córdoba, 2016). Therefore, this research goes beyond the instrumental stream by considering OSR inextricably tied to the core concept of responsibility.

3. Statement of the problem

It is likely to find only one of the two agency problems in Latin America. It seems that there is no place for the principal-principal problem. Indeed, the stock markets are not developed enough, so the Majority-Owners-Block (MOB) does not need more control. Consequently, the principal-agent problem arises as to the central aspect through the board of directors-CEO conflict of interests. That is the MOB-CEO conflict of interest.

The struggle lands on OSR decisions. The uncertainty about OSR revenues, and the inherent difficulty of measuring them, makes the struggle harder. CEOs tend to assure short-run revenues since there is no guarantee they will stay hired for the organization in the long run. Conversely, the MOB expects to support their family welfare on the long-run existence of the organization (Jain and Jamali, 2016; Lau, 2010).

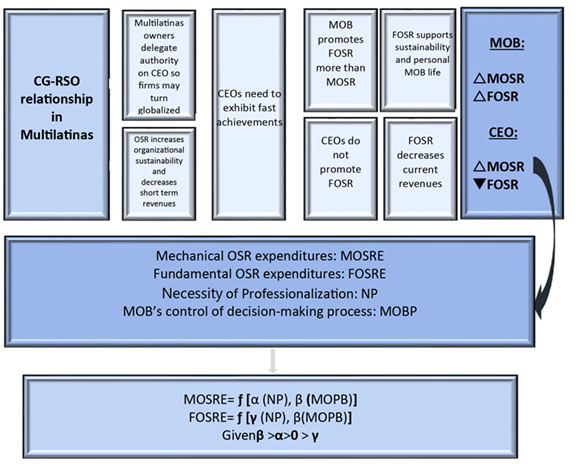

This struggle may be divided into the OSR’s two parts. As can be seen, MOB tends to support sustainability. Nevertheless, the CEO tends to favor rapid revenue. That is, the MOB supports FOSR, and the CEO supports MOSR. Further, the high power of CEOs increases in Multilatinas because these organizations face Professionalization’s processes as a part of their strategies to get globalized. It follows that, currently, Professionalization mediates the CG-OSR relationship in Latin American multinational firms.

At first, the struggle varies according to its relation to FOSR or MOSR. The MOB and CEO agree that risk-avoidance and favorable organizational image are desirable traits, so MOSR seems not to be a disputable subject. On the flip side, MOB wants to increase the organization’s expenditures on FOSR acts. Consequently, MOB bets to assure social welfare, making organization sustainability feasible. On the contrary, the CEO does not want those expenditures since they reduce the short-run revenues.

Therefore, the OSR expenditures depend on the MOB-CEO struggle to control the decision-making process, a political issue usually considered in the codes of good governance. The CEO gains power when the Necessity for Professionalization (NP) is high. It means that organizations have a considerable dependence on the CEO’s knowledge and social networks. When the necessity is low, MOB Power (MOBP, when the MOB controls decision-making) increases due to the CEO’s power displacement.

According to the above, if NP were relatively high, MOSR expenditures (MOSRE) would increase. In contrast, when MOBP is high, and NP is relatively low, both MOSRE and FOSR expenditures (FOSRE) will be increased. Nonetheless, the latter will shift higher.

In sum, MOSRE is directly related to both MOBP and NP. In turn, FOSRE is directly related to MOPB and inversely related to NP. MOBP and NP will always have positive values, as shown in Figure 2.

Source: Adaptation from Tello-Castrillón (2018, p. 61)

Figure 2 The theoretical model of the relationship between CG and OSR in Multilatinas

There, the last square contains the theoretical model which supported the fieldwork. As a model, its core of interest is the relationships between variables instead of their values and has a preliminary and incomplete predictive capacity (Mouton and Marais, 1990). The variables MOSRE and FOSRE were considered slightly different at the beginning of this research. The main difference was the absence of MORSE’s focus on sustainability. Those were called initial analytical categories. The development of research led to changes shown above, that means, the emergent categories.

The Literature review hints that the CG-OSR relationship in Multilatinas has not been studied. This paper might be the first step to understand that subject. By this, Multilatinas would get two benefits: first, they would improve their public image, which results in lower transaction costs. Second, the Multilatinas would dynamize their activities against poverty and support competitiveness improvement as part of Latin countries’ economic development.

4. Methodology

This paper emerges from a five-year research process. The main methodological issues are summarized in Table 1. The literature review suggests this work is one of the first attempts to study the CG-OSR relationship in Multilatinas. That is why it is considered exploratory research. Such a subject hosts several blurred links between the variables. For this reason, the primary purpose of this study focuses on bringing visibility to the links mentioned above, which discards the solving of a practical problem. Consequently, this is a theoretical study.

The selection of an organization to execute fieldwork requires that the proposed characteristics in the theoretical model get matched. Accordingly, Organización Carvajal was chosen since 1) there underwent a Professionalization process since 2011, 2) it was the first Colombian Multilatina to appear, and 3) it has a well-known Latin-American OSR tradition.

As a first-attempting type, this research is tasked with gathering vast information about the subject of study. After that, case study research supports a proper method to execute it (Yin, 2003; Eisenhardt, 1989; Patton, 2002; Eisenhardt and Bourgeois, 1988; Hernández Sampieri, Fernández Collado, and Baptista Lucio, 1991). Because of this, the methodology searched for the qualitative details in this Colombian Multilatina organization to illustrate and reinforce the theoretical model.

The research was developed first by the hermeneutical-heuristic method exploring Organización Carvajal web pages. Since the information was almost entirely up to 2015, this was the final year of the study. Complementary, the period of the study begins in 2011, the initial year of Professionalization.

The information was processed in ATLAS.ti software in two chronological stages. In the first stage, the data were analyzed according to the preliminary analytical categories of the theoretical model. In the second, those categories were improved with the field information. The improvement generated the new emergent categories, which both the model and the case study contain.

5. A brief introduction to Organización Carvajal

At the beginning of the 20th century, la Imprenta Comercial (commercial printer house) was born. La Imprenta was the seminal entity that would become Organización Carvajal (Carvajal Organization) a few years later. The Organización Carvajal adopted several legal names throughout decades, always incorporating the family’s name: Carvajal. To simplify, here it is called Carvajal generically. Manuel Carvajal Valencia was the pioneer (Ordoñez Burbano, 1995; Londoño, 2016) who founded it as a diversified organization. In any case, printing (in a broad sense, the dissemination of information as a whole, nowadays, in a digital way) has remained the core activity. The Carvajal name has been linked not only to business but also to the political stage. Nevertheless, the name is not visible in the public administration in current times.

The family members have a long tradition of being educated in first-world academies. Therefore, Carvajal has been managed under the European and, especially, US streams. The Carvajal development has been tied to the headquartered regional state, Valle del Cauca, which includes the capital city of Santiago de Cali. Carvajal’s contribution was a crucial factor in creating the mentioned state in the early 20th century. The Carvajal and the state grew up together, explaining the permanent Carvajal’s interest in increasing the Valle del Cauca and Cali’s welfare.

According to it, Carvajal has been recognized as a good employer throughout its lifetime. On several occasions, the firm created programs of human talent management many years, often decades, before the rest of Colombian organizations. Complementary to being a good employer, Carvajal has implemented several other programs to promote social welfare. That constitutes its long tradition in the OSR activities.

The Carvajal’s OSR is an autonomous corporate responsibility. Nonetheless, people associate it with another organization whose denomination exhibits the name Carvajal too. That is, Fundación Carvajal (Carvajal Foundation). Since 1961, the Fundación Carvajal has channeled the Carvajal Family’s social commitment by covering 678,936 people, according to 2015 estimations (Fundación Carvajal, 2016). That decade also witnessed the first international incursion of Carvajal by purchasing a printer company in Puerto Rico. Since then, Carvajal has extended its activities to sixteen countries in Latin America, two more countries outside the region, and a commercial presence in fifty countries.

In 2008, Carvajal hired, for the first time, a non-familial CEO: Ricardo Obregón. It seemed to be an attempt to increase added value (Revista Dinero, 2012) and was focused on the organization’s renewal. That broke with a seven generations tradition of having familial CEOs. Obregón worked until 2012, then, since the beginning of 2013, Bernardo Quintero replaced him. The latter still manages this approximately twenty-four thousand employees and eight business units holding.

6. The Carvajal’s CG-OSR Relationship

In 2006, Carvajal renovated its goals as a precise movement to reverse the decreasing tendency of the value-adding (Organización Carvajal, 2010, p. 156). It was named MEGA VISION 2010 and routed the plans and activities of 2011-2015 -until current days-. This plan outlined one of the conditions for hiring a non-familial CEO. The other condition was the problems of information.

The asymmetry of information would likely exist inside this about three-hundred family members. Those who worked at the highest level of Carvajal might have dealt with comprehensive information. Likely, the rest of the family members were not acquainted with that information. Consequently, a principal-principal agency problem arose, and there was no significant difference between hiring a familial member or non-familial CEO (Villalonga and Amit, 2006). In any sense, the new CEO acting diminishes the access of some familial members to privileged information.

To summarize, a non-familial CEO’s arrival probably provided a way to create more added value by reorganizing the whole organization and diminishing the asymmetries of information within the family by keeping family members out of the CEO’s job, the one with the broadest information in the organization.

That new organizational perspective rearranged the organizational structure. It was especially evident in creating an office to deal with the Carvajal OSR as a whole: Organizational Development Office. Furthermore, Carvajal started to formalize its OSR politics. Therefore, in 2010, they defined ten categories of stakeholders: clients and users, collaborators, stockholders, suppliers and creditors, competitors, government, authorities, society, mass media, and environment (Carvajal Internacional, 2011). Besides those, the upstanding labor conditions remained. Nonetheless, in 2011 and 2015, Carvajal shifted from fourth place to twenty-fourth place in the MERCO index of good places to work (Merco, 2013, 2016). All these components shape Carvajal OSR.

Concerning it, Carvajal has firmly declared that its CG is wholly independent of that of the Fundación. However, two reasons might partially blur that declaration. First, Fundación’s CEO is a member of the Carvajal’s board of directors. Second, both organizations work together when it is required.

7. OSR in Organización Carvajal

The Carvajal’s CG rules its OSR. For example, the moral (AKA ethics) of its OSR is included in four articles of the Good Governance Code (Organización Carvajal, 2009, p. 37). Besides, three corporate values are linked to OSR: Integrity, Respect, and Social Commitment. The last is expressly connected with prescriptions issued in ISO 14001, OHSAS 18001 e ISO 9001 (Organización Carvajal, 2009).

The sum of the FOSR and the MOSR configures the Carvajal OSR. The first focused on external stakeholders and sustainability. It was mainly centered on environmental care, the beneficial products to people, and the people’s education. The FOSR is widespread in sustainability reports. On its side, the MOSR targeted internal stakeholders (mainly the collaborators and the correct waste disposal) and improved strategic capacities.

Due to its nature, the MOSR shifted up to become the central part of Organización’s OSR. The activities’ essence matching the MOSR frame might be divided into four dimensions: legal, communitarian, competitive, and environmental. Additionally, the MOSR depended on two main aspects. First, tax incentives since MOSR are related to strategic issues. Second, the innovative academic supplies to improve efficiency.

Carvajal often worked together along with other organizations to execute more expansive OSR plans. Its activity is mainly located in the city of Cali, and its influence almost covers the entire department (state) of Valle del Cauca. It also executes some actions in other parts of Colombia and Latin-American (especially México and Brazil) on a lower scale.

8. CG in Organización Carvajal

The most relevant characteristic of Carvajal CG consisted of a mighty family keeping a superior organization’s power by the MOB’s control of the decision-making process. This control was partially possible since the MOB held the board of directors’ leadership establishing the strategic objectives and disseminating the family and organizational ethical principles. That is a strategic power.

The power inside the organization flew from up to down. For instance, the board of directors had the faculty for creating counseling committees to work with the CEO (Hiring, Wages, CG, Auditing, Investments, and Finance) (Organización Carvajal, 2009, p. 22). Another example is that OSR was widespread due to the endorsement of a board of directors composed of most independent members.

In addition to strategic power, the board of directors had operative power as well. It was represented in three aspects: 1) the control for approving operative plans, 2) the faculty to approve and monitor CG 3) the allowance to hire people to occupy jobs hierarchically next to the CEO. Therefore, all those conditions resulted in the board of director’s power trespassing upon the CEO’s power.

The numerals are evidence that the Classic Agency Problem was not present in Carvajal. This relative absence of a board of directors-CEO conflict is explained for three main reasons: A highly professional capacity of the board of directors, a solid organizational culture related to OSR, and the member’s respect for traditions, including respect for hierarchy, inside the organization. All of these suggest that the agency problems were ex-ante solved even by using personal relationships.

Furthermore, the MOB power seemed not to generate problems inside itself. That is, there was no Principal-Principal agency problem. Additionally, the family’s affairs were dealt with in diverse ways: Ombudsmen, egalitarian stock sharing, and relationships guided by a family code. The inner equilibrium matched the attention that Carvajal’s system paid to the environment.

Carvajal was an open system. It recognized that the stakeholders were essential to survive. The board of directors acted as a bridge between the family and the stakeholders. In this respect, Carvajal has tended to avoid external financing. There was only one time when it decided to gather financial resources from outside the organization but not allowing creditors to be part of the decision-making process. So, Carvajal did not share its CG with external actors. Anyhow, the stakeholders remained part of the organization’s strategic interests. To this effect, Carvajal monitored the CEO’s behavior paying attention to its effects on stakeholders, and issued reports of its activities supporting them.

It seemed that Carvajal, concerning OSR, did not distinguish the short-term from the long-term. Instead, the CEO had the conviction that the short-term results build the long-term results. A kind of ambidextrous organization. This relationship has centered the CEO’s attention on the former while setting the board of directors’ attention on the latter.

The long-term focus targeted the fight against poverty. That provided the organization the proximity to poor people that, in the end, became useful for knowing consumers. Notably, there were no references to the owner’s family in the OSR assumptions. The OSR was built only based on its organizational issues.

8.1. The power of the CEO

The core of this power was operational. The CEO played an essential role in CG through operative decisions. These went iteratively from the CEO to the board of directors. The power of the CEO was diminished by the counterbalance between the CEO and the vice-presidents. On the one hand, the CEO was a hierarchical chief over the vice-presidents. On the other hand, the board of directors might replace the CEO with any of the vice-presidents. Remarkably, one of the vice presidents oversaw the whole OSR coordination.

The CEO’s interest in OSR was blurred. There was no evidence to support the CEO’s expected revenues from OSR and the CEO’s position for MOSR and the FOSR. In any case, it seemed that the CEO was close to decision-making about MOSR, primarily focused on its financial aspects. That was something shared with the board of directors. Concerning the FOSR, the CEO promoted it due to his proximity to the board of directors. Nonetheless, this promotion was lower than that of the MOSR. Notably, the data suggested that the CEO trended in favor of the OSR.

9. The theoretical implications

The results obtained here are inscribed in the Organization Theory. They have a place in the group containing the research that links CG and OSR. These findings occur in the emergent markets environment and the inner CG context.

The findings of this paper are confined to the organizations owned by a majority-owners-block with solid family and Christian values. They also must be immersed in the emergent markets where low-developed capital markets are not a threat for changing the property structures. Methodologically, it is limited by working with just one organization, though representative of a Multilatina, and requires more cases to add statistical validity to the current qualitative feasibility. The Case Study Research works well as a methodology for gathering theoretical support to construct a middle-range theory about a new subject. Notably, The Case Study Research supports intensive validation departing from a solid theoretical base. The use of ATLAS.ti well accomplishes that.

The Latin American characteristics also configure a proper kind of OSR that might be considered paternalistic. That means people search for protection from either the powerful or those who represent leadership. This OSR is centered on the fight against poverty and some promotion of personal development. The paternalistic style combines US management and Western European policy styles. That is a combination between the philanthropic market-oriented view and the sustainable view -promoted by the Global Report Initiative- of Social Responsibility. The paternalistic style is associated with Multilatinas’ management style and prepares them, along with non-familial CEO hiring, for globalization.

Calling Professionalization to the act of hiring a non-familiar CEO may suggest that family CEOs are not well suited to manage organizations. Two alternative new terms are proposed here to solve this: degeneticalization or defamiliarization. Those names indicate the CEO is not a part of the family but says nothing about the family’s management capacity and any lack thereof. This reasoning matches up the link between defamiliarization-OSR manage as well.

The organizations may often execute the OSR along with a non-profit foundation. The latter might emerge from the same Mutilatina owners as a humanistic wing of their business core. The foundations meet better the fundamental OSR and, therefore, it is likely they and business core join up their actions. That often blur frontiers between them.

One of the blurred frontiers is set on the political field. The shared name between organizations and their foundations legitimizes OSR. Consequently, the political core of CG, intraorganizational and interorganizational power relationships, is dynamized. In any case, the OSR trends to politically favorable activities: the individuals and group empowerment, the relationships with local and national states, the measurement of social impacts, among others.

A robust organizational culture reinforces a favorable political environment. Therefore, the former complements the CG issues by constructing an organizational culture that promotes organizationally desirable moral values. One of the main consequences is that Classic Agency Problem likelihood is shrunk.

The power of the majority-owners-block explains this diminishing. The block’s behavior might be like that of the family majority-owners-block except for the mediation by family codes. Any block would try to keep its current organizational power and more proximity to FOSR than CEOs. Possibly, collegiate bodies at the strategic organizational level would tend to favor a holistic view of OSR that always holds, at least, a little bit of altruism.

The holistic view implies the necessity of paying attention to efficiency too. Indeed, productivity-based efficiency is a mandatory condition at the beginning and the finish of the OSR. It becomes especially relevant in the MOSR and configures the most significant part of the OSR.

The MOSR importance shifts up considering time. A common standard’s three-year planning horizon makes the MOSR activities more feasible to be executed than the FOSR ones. In the same way, the CG prescriptions meet the MOSR sharply, turning both more operative. That means a focus on people, processes, and technology.

Some last considerations for ending. The core of the CG-OSR relationship would change depending on the researcher’s perspective. From an organizational point of view, the OSR is part of the CG dimensions. From a societal point of view, the CG is part of the social arrangements. Even though the OSR is being promoted as cross-line activity, the organizations tend to conceptualize it as distinguishable activity.