1.Introduction

For decades, human resources (HR) research has been led under the strategic approach that highlights the value of its function within the organization. Its contribution has been directed towards the implementation of practices that allow improving the performance of companies (Kaushik and Mukherjee, 2021). Although there has been disagreement on the type and number of practices that should be taken into account by the organization (Miao, Bozionelos, Zhou, and Newman, 2021), a consensus has been reached on giving more importance to human resources systems than to individual practices (Boom, Den Hartog, and Lepak, 2019).

In this sense, the HR system composed of high-performance work practices (HPWP) could better explain the effects that such practices have on individuals, considering that employees are simultaneously exposed to several practices and the effects that occur will depend on the synergy between these (Boom et al. 2019).

The impact of HPWPs on organizational performance may be the result of the reciprocal relationship between employee and employer, i.e. individuals feel that, through the practices, the organization cares about their development and well-being and, thus, seeks through their efforts to contribute to the achievement of the company’s objectives (Rhee, Oh, and Yu, 2018). However, the literature has exposed that such practices are not perceived as employees should, and their design and implementation by HR managers or managers has been conditioned by their own interests (Baluch, 2017; Ali, Lei, Freeman, and Munuwar Khan, 2019).

In line with these arguments, it has been possible to evidence the growing interest in determining the differences that exist between the practices perceived by employees and those being implemented by HR managers (Khilji and Wang, 2006; Baluch, 2017). In this case, as Xi, Chen, and Zhao, (2019) states, the effectiveness of such practices depends on the degree to which a company’s employees can perceive or experience them.

Along the same lines, authors such as Khilji and Wang (2006) argue that it is necessary to explore the heterogeneity of the implementation of practices in organizations, i.e. to take information from both management and employees and thus be able to study the gap between the two. Likewise, Macky and Boxall (2007) suggest that it is possible that employees may have different perceptions about the scope of human resources practices and that, therefore, one should not rely on a single informant in the organization who has almost always been the one who occupies a managerial level. To these arguments, recent research has offered empirical evidence showing that the way in which HPWPs are implemented in the organization could affect the perception that employees attribute to them (Ali et al. 2019; Xi et al. 2019). For example, Yiang Zhu and Bambacas (2018) found in their research that managers and employees have different perceptions of HPWPs being adopted in organizations located in China.

Taking these arguments into consideration, the purpose of this study is to establish whether there are differences between the perception that employees have of the HPWPs executed in the organization (perceived HPWPs) and the high-performance practices that HR managers claim to be implementing (intentional HPWPs). In other words, the aim is to validate whether there are discrepancies in the intention with which HPWPs are carried out and the perception attributed to them by individuals.

In accordance with this objective, this research aims to contribute in two areas. The first, from the academic environment, where it is necessary to advance in the construction of analyses based on results in Latin American business contexts, in addition to the presentation of a measurement scale with good psychometric properties. The second, in the business environment, where the need to strengthen human resources management through the distinction, consistency and consensus of high-performance practices is evident (Baluch, 2017).

For the development of this study, information was collected in 50 SMEs in Bucaramanga and its metropolitan area, where at least 10 of their employees answered the questions of the instrument, as well as the HR director. The study is empirical in nature and initially included a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) in which the validity of the instrument was verified, and subsequently, a descriptive analysis was performed in which the gap between the information from HR directors and the information from employees was verified.

The structure of the paper begins by presenting a conceptualization of HPWPs, going through different classifications, and concluding with a measurement proposal, based on the literature. Then, the methodology used is explained, where a characterization of the selected companies and the sample is presented. Subsequently, the results of the research are presented, showing the differences between the HPWPs that HR managers claim to implement and the HPWPs perceived by employees. Finally, conclusions are drawn from the findings obtained that contribute to generate a contribution to the area of study from the Colombian business context.

2. Literature review

2.1. Conceptualization of high-performance practices

HPWPs originated in the 1990s as part of the Strategic Human Resources Management trend that sought to align management functions and activities in this area with the organization’s strategy (Kaushik and Mukherjee, 2021). In the literature, HPWPs can be identified as high-performance work systems, high involvement work systems and high commitment management, among others (Raineri, 2017). However, and regardless of the term used, among these denominations there is a common aspect related to obtaining a better performance of the company when they are used together forming a system and promoting through them, the development of skills and capabilities in employees (Kaushik and Mukherjee, 2021).

The definition of HPWP has been offered by various authors. For example, Evans and Davis (2015) conceptualize them as an integrated system of human resources practices that are internally consistent (alignment between the same practices) and externally consistent (alignment with organizational strategy). In the same line and under a more recent contribution, Haar, O`Kane, and Daellenbach (2021) define them as those practices capable of developing a superior workforce that contributes to enhance knowledge, skills and capabilities in employees, making a difference in the market competitors.

The interest aroused by this set of practices in the human resources area is originated by a growing number of researchers who agree with the positive effects of including HPWPs to improve company results (Arthur, 1994; Delaney and Huselid, 1996; Kloutsiniotis, Katou, and Mihail. 2021; Haar et al. 2021; Sun and Mamman, 2021). Thus, different research has been conducted to determine the impact of HPWPs on variables such as performance (Raineri, 2017), innovation (Haar et al. 2021) and affective commitment (Para-Gonzalez, Jiménez-Jiménez, and Martínez-Lorente, 2019), in addition to recognizing that there is a crucial distinction between the intention with which HPWPs are carried out by managers and the perception that employees attribute to the implementation (Ma, Gong, Long, and Zhang, 2021).

2.2. Classification and measurement of high-performance practices

Several proposals have been put forward by authors to classify HPWPs. However, there remains the absence of a commonly accepted classification, which would allow comparative studies based on the results obtained (Miao et al. 2021). In this sense, a review of representative proposals in the literature that facilitate the operationalization of the concept is presented below.

For Arthur (1994), HPWPs are classified into two dimensions called control and commitment, which could shape the attitudes and behaviors of individuals at work. Huselid (1995) argues that the HPWPs adopted by an organization should be aligned with the aspects that are expected to have a positive impact on the employee. Thus, his proposal is based on two aspects: the employee’s skills with the organizational structure; and the employee’s motivation.

In the same year, McDuffie (1995) argued that the inclusion of human resource practices could contribute to improving an organization’s economic performance through the incorporation of the following practices: work teams, problem-solving group, participation, rotation, decentralization, recruitment and hiring, compensation, status differentiation, learning and training. Meanwhile, for Delery and Doty (1996) HPWPs can be appropriated by the organization as a market-type system that focuses on recruiting personnel from outside the organization and as an internal system, oriented to an extensive socialization of activities among the company’s internal personnel. Some of these practices are: career opportunities, training, results orientation, profit sharing, job security, participation and job descriptions.

Similarly, Pfeffer (1994;1998) argues that human resources practices contribute to the development of a competitive advantage through the management of workers’ capabilities and commitment. This author’s proposal indicates seven practices which are: job stability, contracting, retribution, communication, self-directed teams, training and status reduction. According to Camps and Luna-Arocas (2012), this HPWP classification enjoys great academic recognition and in addition, they have been strongly referenced in the literature (Marchington and Grugulis, 2000; Pascual, 2013; Pascual and Comeche, 2015) due to their internal consistency and findings that provide general support in the effectiveness of the implementation of the 7 practices in organizations (Luna-Arocas and Camps, 2008).

Among the most recent classifications is the one presented by Para-González et al. (2019), who argue that proactive organizations link HPWPs with their business strategy and, in this way, mobilize the capacity of individuals towards the company’s objectives. Some of these practices are: selection, training, performance evaluation and compensation.

Similarly, Miao et al. (2021) argue that the components of HPWPs operate in synergy and therefore, the effect they will have within the organization will be characterized by efficiency and will be related to positive attitudes on the part of employees. Some of the practices used in this study were: extensive training, empowerment, results-oriented performance evaluation, competency management, employee selection, information sharing and reward management.

On the other hand, when it comes to measuring HPWP, the researcher is faced with two major decisions. On the one hand, what to measure, i.e., which practices are considered HPWPs, and, on the other hand, how to measure these practices. Regarding the first decision, the approach followed by most authors to measure HPWPs has been to derive the practices from previous studies (Macky and Boxall, 2007). In other words, researchers have identified practices that have been commonly referenced in the literature and used them in their studies. For example, Camps and Luna-Arocas (2012) carried out an analysis based on selected research and chose to group practices following the indications of Pfeffer (1998). Under this same theoretical orientation, Sun and Mamman (2021) made a selection of dominant practices in the Chinese and Western literature with which they were able to pre-validate an instrument to measure them in their research in SMEs.

It was also noticeable that some authors have resorted to the adaptation of existing classifications. For example, Kloutsiniotis and Mihail (2017) adapted Delery and Doty’s (1996) proposal composed of 7 practices to be developed in health care services in Greece and in employees of service and manufacturing companies in China, respectively. For their part, in the research recently developed by Takeuchi, Way, and Wei (2018), the authors carried out the measurement of practices based on nine items from a literature review.

As can be seen, researchers have not used a standard measurement of HPWPs, which has led to the existence of a considerable number of instruments for their measurement. In view of this situation, this paper aims to adapt the questionnaire proposed by Camps and Luna-Arocas (2012) that contemplates the seven HPWPs proposed by Pfeffer (1998) and that, when applied, could contribute to what has been done to date. To this end, previous studies developed by the authors (Camps and Luna-Arocas 2008; 2009) were analyzed and the applicability in other research was reviewed (Pascual, 2013; Pascual and Comeche, 2015).

Now that the set of HPWPs to be measured has been agreed upon, it is time to address the second major decision, which corresponds to how to measure them. In accordance with the way in which HPWPs have been measured, most research has obtained information from managers. Several criticisms have been made of the need to include not only the response of HR managers, but also the perception of HR management. The need to include not only the response of HR managers, but also the workforce’s perception of the use of HPWPs in organizations, has been criticized. For Riaz, Townsend and Woods (2020), employee perceptions are very important because they give meaning to the HR system and, therefore, they should be able to translate the message that managers want to convey through the implementation of HPWPs. To this, Xi et al. (2019) argue that several studies have documented that HPWPs that have been reported by employees tend to present a lower valuation than that reported by HR managers or directors. This could be a result of a limited working relationship, in addition to weak consistency and coherence in HR systems that has contributed to variation in the interpretation and application of HPWPs by managers and employees (Baluch, 2017). In this same sense, for Mierlo, Bondarouk, and Sanders (2018) the perception gaps between the different actors that make up the organization may occur because managers have other objectives, which may lead them to understand the practices differently from what they were designed for.

Based on these arguments, it is important not only to measure HPWPs under a scale that promotes the comparison of results to generate a contribution to the area of study, but also to perform an analysis based on the response of individuals and managers in order to establish the differences that may exist in the perception of their implementation.

3.Methodology

3.1. Sample and data collection

The scope of this research was descriptive and cross-sectional. The information was analyzed under a quantitative approach using descriptive statistics to establish the gap obtained between the HPWPs perceived by employees and the intention of managers when implementing them (intentional HPWPs).

For the selection of the sample, the business information registered in the Chamber of Commerce of Bucaramanga is taken as a basis, which for the year 2017 reported a total of 21,931 SMEs. Due to the difficulty of approaching this large number of companies, it was decided to use a convenience sampling taking those companies that had a representative number of employees (more than 10) and in which the research team had some contact to conduct the study.

Table 1 below presents the characteristics of the empirical study.

Table 1 Characteristics of the empirical study

| Aspects | Empirical study |

|---|---|

| Universe | Employees in companies with more than 10 workers |

| Unit of analysis of the independent variable | HPWP Perceived - Individuals (employees) |

| HPWP Intentional - Organization (HR Director) | |

| Geographic scope | Colombia (Bucaramanga) |

| Type of sampling | For convenience |

| Data collection period | April-June 2018 |

| Information collection instrument | Questionnaire |

| Sample size | 651 individuals, belonging to 50 organizations |

Source: Authors’ own elaboration.

A total of 50 companies participated in the study, with a minimum of 10 employees surveyed in each of them. The 601 employees and the 50 HR managers of these companies were characterized. The profile of the workers who responded to the questionnaire was made up in greater proportion -45.26%- by people between 26 and 35 years of age. Slightly more than half -56.07%- were women, and 47.09% of those surveyed said they were single. A total of 44.42% said they had children and 3 out of 10 had college education. In addition, 38.60% of those interviewed stated that they had been with the organization for between 1 and 3 years. For their part, 42% of the HR managers who participated in this research were between 26 and 35 years old. Approximately 3 out of 4 of those interviewed were women. Sixty-two percent of those interviewed said they were married. Sixty-six percent said they had children, 52% had a specialist level of education and 30% had been working for the organization for between 1 and 3 years.

The data collection process was carried out in those companies that, after receiving the letter with the presentation of the purpose of the study, agreed to participate in it. The collection was carried out through two methods: face-to-face and virtual through a link.

3.2. Instrument for measuring high-performance practices

Following the indications of some authors (Khilji and Wang, 2006; Macky and Boxall 2007; Xi et al. 2019; Ali et al. 2019; Riaz et al. 2020) who argue that, in the analysis of HPWP use, both the worker and the HR manager should be included, it was decided to collect information from two primary sources, taking the same instrument for both cases. The first source was the employees of the organization and in this case the HPWPs were called “Perceived HPWPs” and the second source was the HR managers whose results were called “Intentional HPWPs”.

The instrument used was adapted from the proposal made by Camps and Luna-Arocas (2012) with a total of 21 questions (example: One of the company’s values is stability; The company has objectively and clearly defined job profiles, etc.), using a 7-point Likert response scale, with 1 being “never” and 7 being “always”. Additionally, other demographic questions were asked, such as age, gender, marital status, among others, to characterize the sample.

4. Results

4.1. Validity and reliability of the instrument

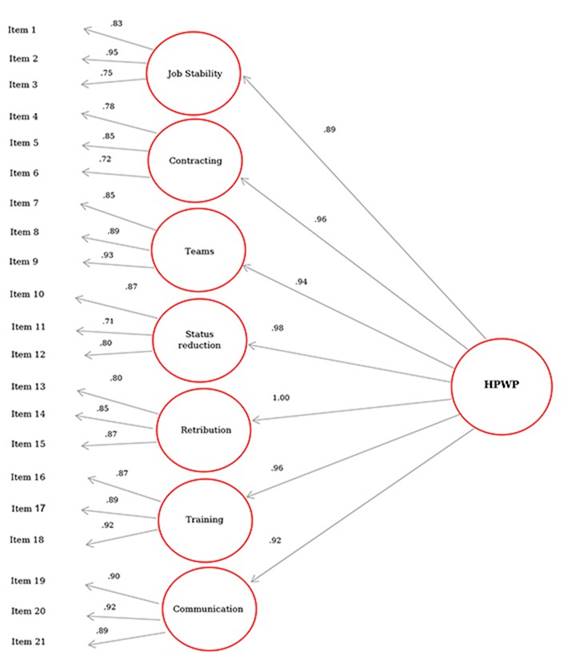

The reliability and validity of the questionnaire used in an investigation are quality indexes of a study. In this case, reliability was determined through Cronbach’s alpha, obtaining 0.958, which is considered acceptable within the established values. On the other hand, the validity of the instrument was determined, as Camps and Luna-Arocas (2012) did, through a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) that allowed a check of the dimensions of the HPWP measurement scale using the AMOS statistical package version 22. Some of the most commonly used indexes to evaluate the fit of the model, according to Escobedo, Hernández, Estebané, and Martínez (2016) are: RMSEA (< 0.05), p-value (0.05), Chi-square (2 to 3 degrees of freedom and with limits up to 5) and the RMR (root mean square error) that measures the variances and covariances of the sample. Table 2 shows the fit indices obtained through the CFA that verify that the scale is valid, i.e., that the items that comprise it measure the construct called HPWP. In this case, the p-value is 0.00 and the RMSEA is 0.049, with values less than 0.05 being acceptable. The CFI is 0.774, considered acceptable considering that the chi-square over the degrees of freedom is located between values 2 and 3. In addition, the RMR is 0.219, a number close to 0, which can be considered a good fit. In the words of Morata-Ramírez, Holgado-Tello, Barbero-García, and Méndez (2015), it can be used to measure the construct through such an instrument if the model presents an adequate fit through these indices.

Table 2 Goodness of fit HPWP

| Goodness of fit | S-BChi2 | g.l. | Chi2/g.l | p-value | IFC | NFI | RMSEA | RMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPWP | 456,269 | 176 | 2,59 | 0,000 | 0,774 | 0,685 | 0,049 | 0,219 |

Source: Authors’ own elaboration.

Similarly, Figure 1 shows the factor loadings of the indicators that make up the HPWP concept and that show the correlation between them. For this case, they all exceed 0.7 which corresponds to the cross-correlation index obtained, ECVI 0.871, expressed by Escobedo et al. (2016), who argues that the closer to one the higher the correlation.

4.2. Descriptive results

As mentioned above, the sample of this study was comprised of 601 employees and 50 human resources managers from different economic sectors, which contributed to the fact that, through descriptive statistics techniques, the gap was established between the responses offered by the employees (Perceived HPW) and those of HR directors (Intentional HPWP). Next, the characterization of sample c is presented, where it can be seen that the majority of participating companies were from the commercial sector with 22% and the transport sector with 20%.

Table 4 shows that almost all practices have a mean close to 5, in the case of the employees’ perception, which in our scale corresponds to “frequently” and 6 in the case of the managers’ response, which is the Intentional HPWPs and therefore would be closer to “almost always”.

Table 4 Mean and deviation of the HPWPs

| Perceived | Intentional | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPWP | Mean | Standard deviation | Coefficient Variation | Mean | Standard deviation | Coefficient Variation |

| Job Stability | 5,20 | 1,363 | 26,21 | 5,91 | 1,110 | 18,78 |

| Contracting | 5,12 | 1,329 | 25,96 | 5,95 | ,847 | 14,24 |

| Self-directed teams | 5,22 | 1,346 | 25,79 | 5,81 | ,972 | 16,73 |

| Reduction of status | 5,38 | 1,208 | 22,45 | 6,02 | ,869 | 14,44 |

| Retribution | 5,00 | 1,476 | 29,52 | 5,850 | ,860 | 14,70 |

| Training | 5,24 | 1,400 | 26,72 | 5,77 | 1,033 | 17,90 |

| Communication | 5,40 | 1,378 | 25,52 | 6,090 | ,886 | 14,55 |

Source: Authors’ own elaboration.

On the other hand, it is evident that the relative variabilities expressed from the coefficient of variation among employees are usually greater than among managers, which means that the opinion of managers is more homogeneous than that of employees. However, it is worth noting that the HPWP with the lowest mean according to employees is that of compensation, but that for managers it occupies the third position on the basis of the scores from lowest to highest. In other words, for an employee, compensation is not always in line with what it should be, but the manager considers that this is an issue that is going well within the organization.

With respect to the Intentional HPWPs, it can be seen that the lowest ranked is training, while for employees this practice is in a middle position, i.e., the manager thinks that training could be improved while the employee does not consider the training he receives to be one of the worst practices (it is 5th out of 7).

On the other hand, the HPWP with the highest average is communication, both in Perceived and Intentional, followed by the HPWP of status reduction, which occupies a second level for both groups. In short, for both employees and managers, actions focused on communication and reducing distinctions between members of a company contribute to generating value for themselves and for the organization.

Given the difference in means observed previously, it is worth asking whether this difference is statistically significant, for which an analysis of the difference in independent means has been carried out (see Table 5) based on the t-student distribution, which shows that the results of employees and managers differ significantly with a level of significance or probability of Type I error of less than 1% (p<0.01). This leads us to be able to affirm that the responses of both groups are different and, therefore, to continue with their analysis.

Table 5 Test of equality of means

| t-test for Equality of Means | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t | df | p-value | Significant Difference | Error difference | 95% Confidence Interval of the difference | ||

| Inferior | Superior | ||||||

| HPWP_Job Stability | 3,806 | 649 | ,000 | ,7557959 | ,1985973 | ,3658250 | 1,1457668 |

| HPWP_ Contracting | 4,518 | 649 | ,000 | ,8706378 | ,1927105 | ,4922264 | 1,2490492 |

| HPWP_Self-managed teams | 3,189 | 649 | ,001 | ,6275097 | ,1967779 | ,2411115 | 1,0139079 |

| HPWP_Reduction_of_status | 3,867 | 649 | ,000 | ,6805546 | ,1760126 | ,3349317 | 1,0261776 |

| HPWP_ Retribution | 4,238 | 649 | ,000 | ,9093178 | ,2145435 | ,4880347 | 1,3306009 |

| HPWP_Training | 2,727 | 649 | ,007 | ,5592124 | ,2050457 | ,1565794 | ,9618454 |

| HPWP_Communication | 3,611 | 649 | ,000 | ,7261342 | ,2010891 | ,3312705 | 1,1209980 |

Source: Authors’ own elaboration.

5. Discussion

The purpose of this study is to determine whether there is a difference in the use of HPWPs between managers and employees of SMEs. According to the results obtained, it can be established that the intention to use HPWPs obtains a valuation by human resources managers very close to value 6, which in our scale is equivalent to their use being “almost always”, which leads to the assumption that, as stated in the literature, companies consider that employees developed through HPWPs contribute to creating profits (Rhee et al. 2018), due to the fact that the adoption of these practices could be influenced by the type of strategy followed by SMEs (Sun and Mamman,2021). Regarding some specific practices, such as training, it should be recalled that, for Hau-Siu Chow (2012), these practices affect the performance of companies by increasing the skills and capabilities of employees, in addition to motivating them to perform.

On the other hand, the findings on HPWPs used in this study would confirm what some authors say that practices form a “pack”, which have to be implemented jointly (Kaushik and Mukherjee, 2021) to generate a synergistic relationship and thus, improve the skills and effort of employees (Huselid,1995). As argued by Raineri (2017) HR practices implemented in a coherent system have a greater effect on organizational outcomes than the sum of the individual effects of each practice separately.

Similarly, it was possible to note the differences between Perceived and Implemented HPWPs, i.e. our study supports the literature that says that such a difference exists and endorses the importance of continuing to make a distinction between the practices that a manager claims to implement and those that an employee perceives (Nishii, Lepak and Schneider, 2008; Ali et al. 2019), thus following previous studies, such as Khilji and Wang (2006) and Yiang Zhu and Bambacas (2018), which also reported inconsistencies between intended and perceived or implemented practices. In this sense, it could be mentioned that there is a disconnect between what management claims to implement in a group of employees and the practices actually experienced by those individuals.

On the other hand, it is notable that the HPWPs analyzed in this research are perceived less than what HR managers believe they are implementing, which corresponds with what is expressed by Xi et al. (2019), who argue that most of the empirical studies identified in the literature present a lower valuation of HPWPs by employees than what is reported by managers.

Among the differences to be highlighted in this analysis is compensation, which presents one of the most important differences on average between employees and managers, with HPWP being perceived as lower, while managers do not seem to indicate their consideration of implementing it in a very different way from the rest of the practices. For Serrano and Barba (2011), this could be explained by the fact that employees do not see productivity as a reflection of their salary, causing demotivation among them. For the authors, this situation could be remedied to the extent that it becomes evident that the greater the effort, the greater the reward. Pfeffer (1994) argues that the level of salaries sends a message to the company’s workforce as to whether they are really valued or not, according to their salary.

Another striking finding is HPWP training, which also has a much higher average among managers than among employees, but the former place it in last place. Training is reflected in actions that develop the appropriate skills for individuals to assume responsibilities in the performance of their position (Pfeffer, 1994), therefore this difference in valuation could be indicating that, according to managers, it is not enough to hire the best, but they must be adequately trained so that the useful life of their knowledge and skills is durable; on the other hand, employees are not perceiving this practice as worse implemented than the rest, which could mean that they do not detect a relevant lack of the necessary skills to perform their tasks. A more detailed study of this practice would provide valuable considerations for the training policy of companies.

6. Conclusions

Throughout this paper we have reviewed the academic literature on the use of certain human resources practices known as HPWP, which, when implemented jointly and aligned with the business strategy, it seems clear that they improve the performance of individuals and, therefore, of the organization. Specifically, significant contributions have been made in the area of human resources that will contribute to continue researching HPWPs to strengthen the relationship between the individual and the organization.

In the first place, a scale for measuring HPWPs is provided, which has been shown to be valid and reliable based on a CFA. In addition, the adjustment indexes that are favorable for the validity of the instrument in empirical studies are obtained, which means a contribution for other research carried out in SMEs where it is desired to delve into the subject. This contribution is added to that previously made by authors such as Camps and Luna-Arocas (2012), who in their eagerness to consolidate an instrument to measure HPWPs and subsequently contrast the results, verified through their studies the contribution made by Pfeffer (1998) and validated in other research (Pascual, 2013; Pascual and Comeche, 2015).

Secondly, the results obtained show that there are statistically significant differences between Intentional HPWP and Perceived HPWP. In this sense, it is concluded with the importance of establishing a human resources management philosophy where communication between managers and employees is integrated to strengthen high performance systems and through them, improve the perception that individuals have about the intention that management has when implementing this type of practices (Riaz et al. 2020).

With the findings found in this study, it can be concluded, as Sun and Mamman (2021), that the positive relationship between HPWPs and employee outcomes cannot be assumed automatically, but that it is necessary to continue investigating the perceptions that individuals attribute to HPWPs implemented by managers, with the purpose of making adjustments in their incorporation. This supports an interesting future line of research that could provide valuable results in the field of human resources, especially in SMEs. As expressed by Khilji and Wang (2006) and Ali et al. (2019), studies aimed at understanding how multiple HR practices impact individuals are scarce. Most empirical research has focused on analyzing a list of practices that are implemented, rather than analyzing those that are perceived by individuals and impact their behavior (Makhecha, Srinivasan, Prabhu and Mukherji, 2018).

The above conclusion has important implications in the professional field for managers in the development of personnel policies. As expressed by Baluch (2017), human resources systems must be sufficiently robust, consistent and achieve consensus among the parties so that they do not send ambiguous messages and contribute to the company’s performance by motivating employees to adapt the desired attitudes and behaviors that, in the collective, help to achieve the organization’s strategic objectives.

Likewise, these results aim to reinforce the conclusions of Bos-Nehles and Meijerink (2018), who mention that practices designed by top-level or HR managers have limited effectiveness unless employees put them into practice or experience them. In this sense, the implementation of HPWPs should be a process that is carried out together with individuals so that they perceive the intention with which they were designed, i.e., to promote their well-being and contribute to meeting the organization’s objectives.

Finally, despite the effort of all research to be rigorous, the work suffers from certain limitations, the most relevant being the data collection process, since it is difficult to guarantee that employees responded fully understanding the items and with no intentions other than purely objective ones. In addition, although the total number of responses is sufficiently high, it comes from only 50 companies, which opens an opportunity to approach the data from a multilevel analysis required in future research.