1. Introduction

Human migration is an issue of global concern, as it affects more countries around the world (Fernández, 2011). This has led international migration specialists to come together to discuss good practices, empirical data, proposals and recommendations, so that more governments can acquire good tools and arguments to establish a Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration (CEPAL, 2018). However, people who migrate face strong inequalities that prevent them from having the same opportunities in the labour market as native people, and these dissimilarities are due to hate speech against groups of people who migrate (Alvarado, 2019), and whose repercussions are worse for women than for men. According to UN Women (2020), women migrate to obtain work that improves their living conditions, but they end up marginalised in jobs with low wages and precarious protection, as well as failing to have the same working conditions as men in the labour market.

In the academic context of the American continent, the idea that inequality between migrant women and men in the labour market causes migrant women to be paid less than migrant men has been discussed, but how race, ethnicity or nationality can influence this inequality has not been explored in depth. South America is considered an expulsion region, as there is a tendency to emigrate. Thus, 8.4 million people emigrate, compared to 4.8 million who immigrate (Stefoni, 2018). In the continental scenario, features of xenophobia, labour abuse, discrimination, prejudice and stereotypes have been identified, for example, the experience of Afro-Colombian immigrant women in Chile (Silva, et al, 2018).

In the US context, it is worth noting that wage inequality between immigrant groups from Latin America and native American groups has been studied in the scientific literature (Gammage and Schimmit, 2004; Caicedo, 2010), but here emphasis should be placed on those who worked with the most vulnerable groups, such as immigrants. Ammons et al. (2016) tested the differences that exist in family-work conflicts in different ethnic groups in that territory, by disaggregating men from women according to their ethnic group thanks to the perspective of intersectionality. The authors conclude that in work-family conflicts, race and ethnicity are more relevant than gender, as significant race/ethnicity differences between blacks, whites and Hispanics were also present when comparing men and women.

On the other hand, Ramírez-García and Tigau (2018) worked on the integration of high-skilled Mexican women into the US labour market over the last three decades, compared to Mexican males, non-Hispanic native-born white women and other immigrants. They found that differences in the labour market insertion of Mexican women were explained by educational level, ethnicity and gender differences, leading to gender segregation; also, that women have an easier time than men in entering a high-skilled occupation. However, Gandini (2019) concluded that this did not always mean greater freedom, autonomy or independence for women, since in some cases migration is involved in processes of segregation and segmentation with gender biases, and therefore proposes that this population should not be viewed homogeneously.

In this context, the aim of this paper is to analyse the wage discrimination of South American immigrants, taking as a reference group the native population classified as non-Hispanic whites and Afro-Americans, by sex, in the US context. Thus, the research is developed in five moments: in the first moment, the theoretical foundation that explains wage discrimination between women and men is exposed through the theory of human capital, the division of the labour market, feminist theories, as well as the incorporation of the components: migration (discrimination by nationality) and race (discrimination by race in the United States). In the second part, the data source and descriptive aspects are explained. In the third step, the methodology used by Oaxaca (1973) and Blinder (1973) to study wage discrimination is employed in the research. In the fourth part, the estimation and results of the research are presented. Finally, the conclusions of the paper are stated.

2. Theoretical background

2.1. Gender wage discrimination

This discrimination is addressed by human capital theory, labour market parcelling and feminist theories.

2.1.1. Human capital theory.

For neoclassical theory, from the perspective of labour demand, it is often the case that jobs requiring a higher level of education, experience or training are offered to men and not to women (Anker, 1997, p.347). This is because it is often claimed that women have higher rates of absenteeism, more frequent lateness or higher turnover rates. The theory explains this from Becker (1971) with the assertion of an employer’s prejudice against certain types of employees, while from the “compensatory differences theory” the burden of responsibility falls on women, who prefer some jobs over others (Anker, 1997, p. 348).

For his part, Mincer (1974) worked from the idea of market rationality to explain the relationship between job training and the wage gap: when a company grows, it will require more qualified workers, which will mean paying them more than the others, and thus the gap is formed. In the same way, based on Gary Becker’s advances, according to Mincer (1974), there is a linear relationship that allows us to calculate the contribution of schooling and experience to workers’ earnings (Cardona et al., 2007, p. 16; Mincer, 1974, p. 52). That is, based on this theory, it should be stated that under normal conditions better qualified employees should receive higher wages.

2.1.2. Parcelling of the labour market.

Theories around labour market parcelling assume that institutions such as large firms and trade unions influence hiring choices and that labour markets are segmented and that it is difficult to move between these parcellations (Anker, 1997, p. 351). In this case, the one based on the sexual division between “female” and “male” occupations is of interest, which leaves many women confined to “female” occupations where they receive low wages (Bergman, 1974 and Edgeworth, 1922, as cited in Anker, 1997, p. 351); according to the author, this results in men enjoying higher wages, as they benefit from less competition in a wider range of occupations (Anker, 1997, p. 351).

2.1.3. Feminist theories.

These theories indicate that the patriarchal system acts as a generator and reproducer of differences between women and men in the labour market. This patriarchal order is responsible for constructing social relations, as well as power relations, with an androcentric and universal character that makes women invisible (Carrasco, 2001), while exposing them to situations of social inequality. Historically, these dissimilarities are related to the sexual division of labour and according to Fernández (2006), men are linked to the public space because they show power, excellence, wisdom, dominance and efficiency; furthermore, the public sphere is tangible, visible, remunerated and has been linked to politics, commerce and international affairs, while the private space is associated with the feminine, reproductive, traditional, static, conservative, familiar, emotional and unpaid.

In this sense, patriarchal gender stereotypes make it difficult for women to earn the same wages as men in the labour market. Feminist economics therefore uses the concepts of the glass ceiling and the sticky floor to explain this scourge. The glass ceiling is considered as a surface that is composed of artificial and invisible obstacles, subject to the prejudices present in organisations, which make it difficult for women to advance in their careers (Wirth, 2001), while the sticky floor acts as an obstacle to women’s professional process. This reality places women exclusively in the domestic sphere and prevents them from accessing relevant jobs (public sphere) (Olidi, et al., 2013), as well as causing women to occupy jobs with little responsibility and low salaries (Wirth, 2001).

2.1.4. Wage discrimination on the basis of nationality.

The theory states that population groups that migrate in search of employment opportunities earn lower wages than native population groups due to nationality discrimination (Aguilar-Idáñez, 2014). This phenomenon consists of generating ethno-stratification in the labour market, i.e. native and autochthonous people are hierarchised in the labour market. This classification means that immigrants’ wages are conditioned by their place of origin and not by their professional skills (Aguilar-Idáñez, 2014). In this sense, immigrant labour is displaced to unskilled, low-paid, dirty and risky jobs (Parella, 2000). However, foreign women suffer more than immigrant men from ethno-stratification, because the condition of being women and immigrants aggravates their precarious working conditions, as well as the absence of inspection systems and protection of labour rights that they face (Paviou, 2017).

2.1.5. Wage discrimination by race in the United States.

Several studies have empirically explored wage inequalities in the United States on the basis of race (Darity et al., 1995; Durden and Gaynor, 1998; Gwartney and Long, 1978). According to Jaynes and Williams Jr. (1989), as cited in Waters and Eschbach, (1995, p. 426), between 1950 and 1982 the white male population improved their earnings from 20% to 32%, while the black male population improved from 6% to 20%. Authors such as Waters and Eschbach (1995) also add the economic restructuring of the late 1980s as a series of changes that affected the black population: declines in mid-level jobs, the redistribution of manufacturing, and the emergence of early inequities among workers of all races as a cause for pessimism about a rapid narrowing of the wage gap. Empirical research has shown that this disparity becomes greater when looking at differences between men and women (Durden and Gaynor, 1998, p. 101).

3. Data source and descriptive aspects

For the development of this research the source data from the 2019 Current Population Survey (CPS) is used, retrieved from the IPUMS (Flood et al., 2019). This survey is the main source of information about the employment statistics for the resident population in the United States. This is conducted each month and contains a sample size of approximately 60,000 households that are selected using a probability test to represent the civilian population and members of the armed forces, living in civilian units or on military bases (Flood et al., 2019).

The population surveyed were 316,074,571 people, of which 50.4 percent represent the economically active population or those in the labour force. This research focuses on three population groups in the United States, composed by the non-Hispanic native white population, with a percentage rate of 84.5 percent, where 51.8 percent is composed by men and 48.2 percent by women; the Afro-American population with a percentage rate of 13.1 percent, composed by 42.8 percent of men and 57.2 percent of women; and the South American immigrant population with a percentage rate of 2.4 percent, composed by 49.1 percent of men and 50.9 percent of women.

According to the CPS data for the year 2019, as shown in Table 1, the Afro-American population group earns a lower average hourly salary in comparison to the salary of the white non-Hispanic native population group, which in total earns 71 percent in comparison to the salary of the white population group. The Afro-American population group has the smallest gender wage gap of the three groups, where females earn 87.9 percent of the total wage paid to males in the same group.

Table 1 Wage ratio between population groups based on gender in 2019

| Reference population group | Native White non-Hispanic (%) | Men of each population group |

|---|---|---|

| Total | Women (%) | |

| Native White non-Hispanic | ___ | 74.2 |

| Afro-american | 71.6 | 87.9 |

| South-American immigrant | 83.1 | 77.0 |

Source: Self-estimates, based on Current Population Survey (CPS) 2019.

In terms of the population group of immigrants from South America in comparison to the non-Hispanic native white population, it is observed that they earn about 83 percent of the total wage of the reference group. In addition, it is evident that immigrant women and men have the highest wage gap, as they received 77 percent of the total wage in comparison to their male counterparts. However, the largest wage gap between men and women is found when analyzing the non-Hispanic native white population group, although this group earns higher wages compared to the other two groups, non-Hispanic white non-Hispanic native women are paid 74.2 percent in comparison to their male peers in the same population group.

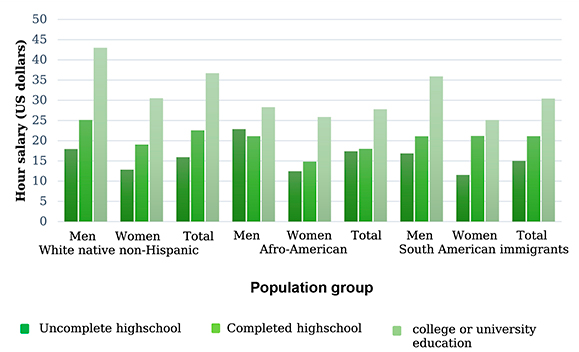

Mincer (1974) states that the level of human capital has a direct impact on the wage level of each individual. Graphic 1 shows that the non-Hispanic native-born white population with college or university education receive higher average hourly wages. This group earns an average hourly wage of $36.7; however, men in this group are paid more than women because they earn $12.47 per hour more than women.

Source: Self estimates based on the Current Population Survey (CPS) 2019.

Graphic 1 Average hour wage classified by sex and population group

For the population group of immigrants from South America with a college or university education. Graph 1 shows that they receive an average hourly wage of about U$30.4. However, men receive ten dollars per hour more than women, while those with a completed high school receive an average hourly wage of U$21.12 independent of their sex.

On the other hand, the Afro-American population receives lower wages compared to the other two population groups, independent of their level of education. In addition, there is a greater wage difference between men and women who have completed high school and incomplete high school, the men earning an average of ten dollars per hour more than women. Meanwhile, this difference in people with college or university education is an average of three dollars per hour.

In addition, occupational segregation is another aspect that influences the remuneration of population groups. First, through a statistical analysis based on 2019 CPS data, it is observed that the immigrant population group tends to be employed in low-quality jobs. Immigrant men have higher participation as janitors and building cleaners, and immigrant women work as maids. Although more than sixty percent of them have college or university education, in many cases, the levels of education and skills are not comparable between countries, forcing them to be employed in any type of occupation (Chiswick et al., 2005).

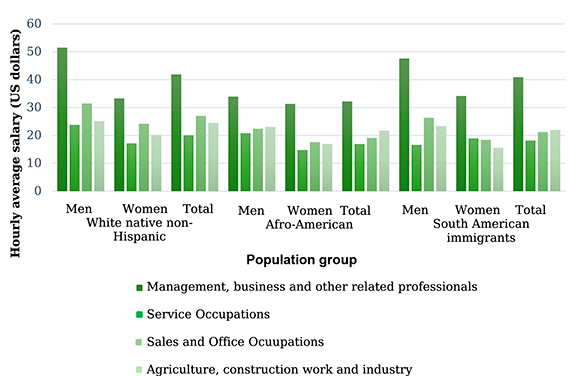

Furthermore, Caicedo (2010) proposes that the divisions in occupations according to place of origin and sex are the result of market transformations and the new demand for labor that “derives from a series of ideological representations that persist in society regarding the role that individuals should play according to certain visible characteristics” (Caicedo, 2010, p.196). These aspects have increased occupational segregation and had an impact on salary levels. In this order, graph two shows the relationship between average hourly wages and the type of occupation for each population group.

In general terms, Graph 2 shows that the management, business and other related professionals earn a higher average hourly wage than in the rest of the occupations. However, there are significant differences between the wages received by men and women. The largest disparity is found in the non-Hispanic white population group, with women earning 35.3% less than men.

Source: Self estimates based on the Current Population Survey (CPS) 2019

Graphic 2 Relationship between avareage hour wages and occupation type

Finally, if we look the management, business and other related professionals, the South American immigrant population and Afro-Americans earn one dollar per hour and ten dollars per hour less compared to non-Hispanic native-born whites. The rest of the occupations show a larger wage gap between the three population groups, in favor of the non-Hispanic native white population.

4. Methodology

The research is developed from a quantitative methodology of correlational nature, which aims to find the reasons or causes that cause certain events, occurrences or phenomena (Del Canto and Silva, 2013). This study analyzes the factors that influence wage discrimination among the non-Hispanic native white, Afro-American and South American immigrant population groups, by sex, in the U.S. labor market.

Therefore, this study proposes an Oaxaca’s (1973) and Blinder’s (1973) decomposition. Oaxaca in his study decides by “estimate the average extent of discrimination against female workers in the United States and to provide a quantitative assessment of the sources of male-female wage differentials” (Oaxaca, 1973, p. 693). This analysis is divided into two parts: one part reflects the differences in the characteristics of the level of human capital, type of occupation, migratory aspects, among others. The second part is the unexplained component attributed to the discrimination exercised by the labor market.

This decomposition uses ordinary least squares estimation to control for some of the proposed visible characteristics, and then decomposes the gaps through a adjusted regression model (Oaxaca, 1973, p. 695). This model is described as follows:

Where, 𝑊𝑖 is the wage of men and women, 𝑍𝑖 is a vector with individual characteristics, 𝛽 is a vector of coefficients, 𝑢𝑖 a disturbance term, and 𝑖 represents the number of observations from 1 to n. Oaxaca (1973) referencing Becker defined the market discrimination coefficient as the percentage wage differential between two types of perfectly substitutable labor, specified as follows:

Where (𝑊ℎ/𝑊𝑚) represents the wage ratio between men and women, and (𝑊ℎ/𝑊𝑚)0 represents the wage ratio between men and women in the absence of discrimination. After some mathematical procedures and simplifications (Oaxaca, 1973, p.695), one can describe the gap decomposition as follows:

Where 𝑍ℎ and 𝑍𝑚 are vectors of average values of the male and female regressors, respectively. 𝛽ℎ and 𝛽𝑚 are the coefficient vectors of the regressions to be estimated. This equation reflects the wage decomposition in two parts. The first part made up of △𝑍𝛽𝑚, that explains the wage gap through differences in human capital characteristics between men and women or other population groups. While the second part 𝑍ℎ△𝛽 could be attributed to discriminatory treatment in the labor market.

In this study, the dependent variable is the logarithm of the hourly wage, and the explanatory variables are the z-vectors associated with the average values of the individual characteristics of each population group. This vector is formed by some variables on human capital, demographic and economic characteristics.

In the group of variables on human capital, age was included as a continuous variable and as a proxy for work experience; and schooling as a dummy variable with three categories, “no schooling”, “completed high school” and “college or university education”. The group of variables with demographic characteristics includes dummy variables such as marital status with three categories “Single”, “Unmarried or married” and “Ever married”, and citizenship with two categories “Permanent citizenship” and “Other case” that includes non-citizens or people born of American parents abroad.

The group of economic characteristics variables includes dummy variables such as labor time with two categories “full time” and “part time”. The occupations divided into four categories “Management, business and other related professionals”, “Service occupations”, “Sales and office occupations”, and “ industry, construction and commercial occupations”.

5. Results and discussion

The estimation of the general ordinary least squares model to control the labor force variables yielded significant coefficients for all the variables proposed (Table 2). This provides a solid basis for decomposing the wage gap and examining wage discrimination of South American immigrants, taking as a reference group the native-born population classified as non-Hispanic whites and Afro-Americans, by sex, in the United States context.

Table 2 shows the largest wage gap in the Afro-American population group in comparison to the non-Hispanic native white population group in 0.24 log points, explained on one hand by differences in the averages of individual characteristics in 57.5 percent and another hand by discriminatory treatment in 42.5 percent. The variables related to being married and being in the service sector are the ones that increase the wage gap the most. The variable “married” has been included under the assumption that married people may have higher wages, because supporting a family is related to the search for higher quality jobs, and therefore better wages, and in this case, it is observed that the Afro-American population group on average has the lowest percentage of married people. In addition, they have a higher participation in the service sector, which is considered to be a low-quality and therefore low-wage job.

Table 2 Results of the inadequacy of the pay gap between population group

| Reference group: White, non-Hispanic native speaker | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| salary gap | Endowment | Percentage | Discrimination | Percentage | |

| Afro-American | 0.2442 | 0.1405 | 57.5 | 0.1037 | 42.5 |

| South-American | 0.1858 | 0.0551 | 29.7 | 0.1306 | 70.3 |

| Variables with the greatest weight in the increase of the wage gap | |||||

| Afro-American | |||||

| Variables | Media | Endowments | |||

| Native (%) | Afro-American (%) | Δz *βa | |||

| Unite | 62.3 | 35.8 | 0.0405 | ||

| Service Occupation | 13.4 | 22.9 | 0.0455 | ||

| South-American | |||||

| Variables | Media | Endowments | |||

| Native (%) | South-American (%) | Δz *βs | |||

| Sex | 48.3 | 50.9 | 0.0730 | ||

| Service Occupation | 13.4 | 24.3 | 0.0524 | ||

Source: Own calculations, based on Current Population Survey (CPS) 2019.

On the other hand, there is a gap of 0.18 log points in the case of the South American immigrant population group, which is less compared to the Afro-American population group. However, in this case, the 70.3 percent could be explained by unequal treatment by the labor market, while the explained component comprises the remaining 29.7 percent. Furthermore, in the explained component, the South American population group has average individual characteristics that tend to behave like that of the non-Hispanic native white population group; however, variables such as gender and being in the service sector contribute to the increase in this gap. Thus, the fact of being male or female has a major impact on wage levels.

In this case, the estimations yielded the results shown in Table 3 with respect to the salary decomposition between men and women in each population group1.

Table 3 shows the largest wage gap between men and women in the non-Hispanic native white population group in 0.248 log points. While the wage gap is 0.225 log points between women and men for South American immigrant population group. For the Afro-American population group is 0.129 log points. In all three cases, we observe that discrimination is the aspect that explains almost all of these gaps. However, the sign of the “explained component or endowments”, which is composed of women’s individual characteristics, shows that women have a disadvantage compared to men, because they earn lower wages than men.

Table 3 Results of gender wage gap production

| Wage gap | Endowment | Percentage | Discrimination | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| non-Hispanic native white | 0.2483 | -0.0339 | -13.7 | 0.2822 | 113.7 |

| Afro-American | 0.1299 | -0.0537 | -41.3 | 0.1836 | 141.3 |

| South-American | 0.2258 | -0.0179 | -7.9 | 0.2437 | 107.9 |

| Variables with the greatest weight in the increase in the gender wage gap | |||||

| Non-Hispanic Native White | |||||

| Variables | Media | Endowments | |||

| Men (%) | Women (%) | Δz *βm | |||

| Service occupations | 11.5 | 16.3 | 0.0223 | ||

| Occupation in sales and office work | 15.9 | 28.0 | 0.0349 | ||

| Afro-American | |||||

| Variables | Media | Endowments | |||

| Men (%) | Women (%) | Δz *βm | |||

| Service occupations | 19.8 | 25.9 | 0.0348 | ||

| Occupation in sales and office work | 15.7 | 26.5 | 0.0371 | ||

| South-American | |||||

| Variables | Media | Endowments | |||

| Men (%) | Women (%) | Δz *βm | |||

| Service occupations | 16.9 | 31.5 | 0.0955 | ||

| Occupation in sales and office work | 12.5 | 25.5 | 0.0615 | ||

Source: Own calculations, based on Current Population Survey (CPS) 2019.

Likewise, the variables with the greatest weight in the increase in the wage gap are related to the type of occupation performed by each population group. The incorporation of some types of occupations such as those belonging to the tertiary sector, in this case services, as well as sales and office work, were employed under the assumption that some tertiary activities are low productivity and poorly paid. In this sector there is a fairly high participation of women. As Weller (2004) argues, women’s participation in this type of sector is related to the increased demand for female labor in informal tertiary activities, especially among the less educated and the most vulnerable, such as migrant women.

Thus, in this paper, the results showed that service occupations, as well as sales and office jobs, caused a larger wage gap in favor of men, because, as shown, women have a higher average participation than men in these types of jobs. For example, non-Hispanic White, Afro-American and South American immigrant women’s participation in the service sector differed by 4.8 per cent, 6.0 per cent and 14.6 per cent, respectively, compared to men in their population group. In the case of occupations in sales and services, this difference is around 11.9 per cent, 10.7 per cent and 13.1 per cent, respectively, compared to men belonging to the same population group.

Some of these results are similar to those found in Caicedo’s (2010) research on the migration of the Latin American and Caribbean population to the United States. In this regard, the author analyzed the occupational distribution of immigrants in the United States and confirmed the high concentration of this population group in low-skilled occupations. Caicedo (2010) also found that there is a tendency for individuals to enter occupations traditionally associated with their gender and that the wage differentials between non-Hispanic native whites, Afro-Americans and immigrants are due, among other causes, to differences in human capital endowments. These similarities therefore support the estimates and results obtained in this research.

6. Conclusions

Analyzing the determinants of wage discrimination among the non-Hispanic white, Afro-American and South American immigrant populations in the US labor market, based on Oaxaca’s (1973) and Blinder’s (1973) decomposition, shows that aspects such as gender, nationality and race cause greater wage discrimination in the labor market, which is biased against the most vulnerable groups such as women, as well as South American and Afro-American immigrant groups.

The results show that women in all three population groups are more skilled than men, but earn lower wages. This could argue a factor of labor discrimination, where variables such as labor market segmentation, according to which a large part of women are related to the service sector, as well as occupations in sales and office work, play a role. According to this idea, certain jobs have been feminized in society, which has limited them to lower paid sectors of the labor market. Therefore, women in the population analyzed are discriminated against in terms of pay because they face obstacles that prevent them from entering positions of responsibility, as well as not being able to reconcile the domestic and work scenarios. This results in women earning lower salaries compared to men as a result of the glass ceiling and the sticky floor (Wirth, 2001).

When analyzing the case by race, it is observed that having a different skin color affects even the level of education and thus the type of occupation. Afro-Americans have individual characteristics that are more disadvantageous compared to the non-Hispanic white native-born population, increasing the wage gap. On the immigrant side, it is observed that individual characteristics tend to behave like the non-Hispanic native white population group, however, they do not manage to obtain the same wage.

In sum, the component of possible unequal treatment by the US labor market largely explains the wage gap, both for women and for the Afro-American and South American immigrant population groups.