1. Introduction

Since the last century there has been a growing interest in the different applications of psychology as a means to improve the quality of life, safety, and wellbeing in the workplace, this discipline it´s known as Occupational Health Psychology (PSO in Spanish) (Salanova et al., 2009). The World Health Organization (WHO, 1948) defines health as “a total well-being state that includes physical, mental and social well-being, and not the mere absence of disease or discomfort”. Based on this definition, PSO encompasses a broader view of organizational health, including both the negative (e.g., stress) and positive (well-being) aspects related to job functioning.

On the other hand, positive psychology (PP) has focused its attention on the processes that contribute to individuals, groups, and institutions flourishing and optimal performance (Blanch et al., 2016), it is defined as the scientific study of optimal human functioning (Seligman, 1999). Since its foundation, PP researchers and practitioners have shown a growing interest in applying these principles to the workplace, as well as collecting evidence of its effectiveness. Different disciplines, such as Positive Psychology Scholarship (POS) (Cameron, 2004) and Positive Organizational Psychology (POP) (Salanova, 2020) propose to recognize those elements that work well in the organizations fostering employee wellbeing. The POP and POS are a growing area of study with valuable contributions from numerous angles and disciplines on increasing the well-being of employees and organizations and having a positive impact on their families, companies, and communities (Adler, 2017; Seligman and Adler, 2018; Seligman et al., 2009). This paper is based upon the theoretical framework formulated by the POP and POS. The authors propose a new organizational model, integrating different elements and perspectives of positive organizational behavior that constitute key elements in promoting organizational wellbeing.

1.1. Organizational Wellbeing, necessity, and competitive advantage

Health within the organizations is an issue that must be addressed with high priority, job stress in the workplace is a chronic problem, which should be considered urgent for organizations (Nixon et al., 2011) There is strong evidence that an unhealthy work environment has a negative influence on employees´ health, in the United States, 61% of the workforce consider that stress has made them sick and 7% have been hospitalized for stress-related causes. In addition, health has a strong economic impact on employers, estimating a cost of US$300,000,000. In Mexico, 75% of the workforce suffers from fatigue due to work stress, which generates negative consequences the emotional (e.g., anxiety, frustration, exhaustion, and demotivation), behavioral (e.g., decrease in productivity and absenteeism), cognitive (e.g., concentration) and physiological level (muscle contraction, headache, back or neck problems, fatigue, increased blood pressure). Annually, five thousand people get sick from work-related causes, which represents 13% of annual productivity (Gutierrez, 2014).

Fostering a healthy work environment can also be a competitive advantage for organizations. In Latin America, only 21% of the workforce reports being actively engaged, while 60% are disengaged and 19% are actively disengaged (Crabtree, 2013). Low levels of engagement can be associated with stress, low productivity, and burnout (Salanova et al., 2000). On the other hand, companies who scored in the higher quartile of engagement report a higher customer satisfaction, greater profitability, and productivity, as well as lower turnover, absenteeism, and fewer errors (Salanova et al., 2011). In addition, people with high levels of well-being report numerous benefits, such as better health (Bertera, 1990), higher wages (Koo and Suh, 2013), and better performance (Böckerman and Ilmakunnas, 2012). Therefore, it is consistent to expect happier workers to also be more productive (Bellet, De Neve, et al., 2019; Bryson and Stokes, 2017; Dimaria et al., 2019). From a financial perspective, healthy organizations report higher growth in their value on the stock market (Edmans, 2012) and higher earnings per share (EPS).

Employees’ well-being also fosters prosocial behavior. People with higher levels of well-being have a positive influence on the community and other people, showing organizational citizenship behaviors (Organ, 1988), inspiring customer loyalty, and increasing other employees´ wellbeing (Harter et al., 2002). In general, promoting employees´ well-being and satisfaction benefits individuals, organizations, and finally, society.

1.2. Healthy Organizations

Organizational practices and resources play an important role in how employees feel engaged and report higher levels of well-being (Gil-Beltrán et al., 2020), they make it possible to distinguish between healthy organizations and unhealthy ones (Wilson et al., 2004). Measuring well-being can be a critical strategy for organizations (Bellet, de Neve et al., 2019; Krekel et al., 2019) and, for countries (Charles‐Leija et al., 2018; Rojas and Charles-Leija, 2022). Assessments can provide useful insights and contribute to having a deeper understanding of people’s motivations, decisions, health, and productivity, as well on the practices and resources that organizations must implement to promote employees´ wellbeing.

A healthy organization boasts financial success as well as a physically and psychologically healthy workforce. However, as (Salanova et al., 2012) point out, organizations must also be resilient, that is, they must have the capacity to face the challenges that come and emerge strengthened from difficult situations, such as the pandemic that is currently being experienced. Organizations that invest in their health and resilience promote higher levels of well-being among workers and that triggers better outcomes. Data provided by Workplace Wellness Alliance indicates that investing in improving organizational health has a return of $3.27 for every dollar invested (Baicker et al., 2010).

Promoting healthy organizations has become also a priority for many countries worldwide as a strategy to address the impact that job stress causes on public health (Queirós et al., 2020). In 2019, the Mexican government pass down the “NOM 035”, a norm that promotes that organizations must prevent or reduce psychosocial risks related to the employees’ activities. Accordingly, POP and PSO can make remarkable contributions to reducing psychosocial health risks in the workplace (Saldaña et al., 2020). POP and PSO researchers and practitioners address this need by integrating new positive organizational models and applying them to the workplace. This paper integrates different elements that have a strong influence on employee’s wellbeing on an organizational model that can be used as a pathway for organizations to promote employee´s wellbeing and reduce psychosocial risks: The BEAT model.

2. Theoretical framework

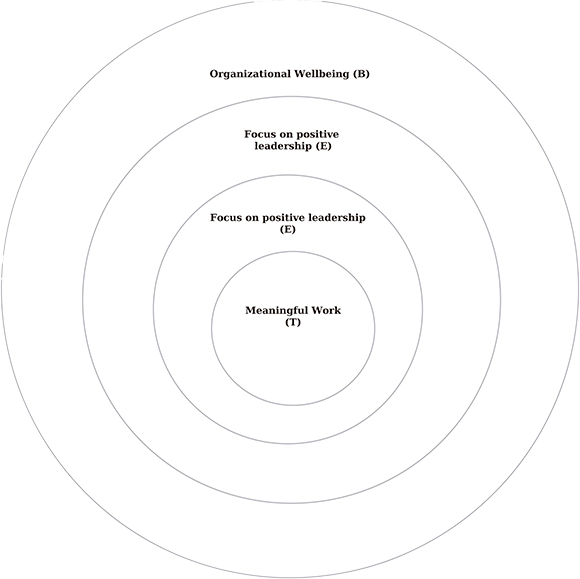

The BEAT model (Figure 1) proposes four elements as the pillars of positive organizations; 1) Organizational wellbeing (B), Focus on a Positive Leadership (E), Positive environments (A), and Meaningful Work (T). BEAT is an acronym in Spanish that refers to the four elements previously mentioned, yet the authors decided to keep that BEAT can also work as an English acronym because it can be a reference to an organization’s pulse.

2.1. Organizational Wellbeing (B)

Organizational Well-being refers specifically to every practice or resource that can contribute to the employees ‘health and wellbeing. Job demands are physical, psychological, organizational, or social aspects of work that require sustained effort and have a physiological and psychological cost on employees (Demerouti et al., 2001). Some examples of job demands can be work overload, boredom with routine, or role conflict.

Job resources, on the other hand, are those physical, psychological, or organizational aspects that help to reduce the harmful effects of work demands, as well as achieve objectives and stimulate personal growth (Bakker, 2011). Previous models like the HERO (Healthy and resilient organizations) model (Salanova et al., 2012) identify resources that enable employees to complete their tasks like autonomy, feedback, and role clarity, as well as other social resources like teamwork and leadership (Nuutinen et al., 2021). On the other hand, positive practices, such as work-life balance, mobbing prevention, psychosocial health, career development, and organizational communication are fundamental resources for employees to overcome job demands. Burnout has direct associations with job demands and a lack of organizational resources (King et al., 2007).

Job demands and resources theory suggests that when job demands are stronger than the resources, employees experience an erosion process that reflects in symptoms of organizational diseases, such as “burnout” (Bakker and de Vries, 2021). Instead, when employees are provided with enough resources, they experience a motivation process that manifests in positive states related to well-being, such as engagement (Salanova et al., 2012a; Schaufeli and Bakker, 2004).

2.2. Focus on positive leadership (E)

The second element of the BEAT model is comprised of the letter E, which represents the focus on positive leadership (in its original conception in Spanish). The importance of leadership in organizational performance has been widely documented (Cameron, 2013; Friedman et al., 2018). From the workers’ standpoint, their leader can contribute to their professional (or even personal) growth, but he can otherwise be a source of stress and worry. If a leader allows employees the possibility of expressing their ideas, they become promoters of innovation. On the opposite, if the leader penalizes new proposals, he will be provoking a behavior reluctant to change in his/her team. Something similar happens when the leader does not address his team with enough respect (Rudolph et al., 2021); disrespect leads people to feel less energy and perceive they are worthless (Dutton, 2003). Several studies highlight the importance of a leader promoting and practicing values such as forgiveness and gratitude in everyday interaction within the workplace (Cameron, 2008, 2013; Cameron et al., 2011).

Positive leadership is distinguished by the following characteristics: positive deviation (achieving above-average levels of performance), affirmative inclination (communicating based on achievements and positive aspects of performance), and eudaimonia (focusing attention on virtuous behaviors). These components are linked to evidence of above-average performance and exceeding expectations work for teams, which can transform problems into opportunities to seek virtuous behaviors (Cameron, 2012). Positive leadership can be achieved by using four strategies.1) compassion-based organizational climate strategies including forgiveness, and gratitude, 2) creating energy networks that promote joy, optimism, and trust in the organization,3) using an affirmative language where the qualities and strengths of workers are highlighted and 4) building community by creating purpose (Cameron, 2012).

This article seeks to highlight the importance of leaders focusing on strengths-based feedback for their teams. We all have strengths that we can take advantage of, as well as being productive, and having moments of complete immersion in the task we perform. In this sense, it is crucial to present the definition of character strengths that have been studied within the realm of Positive Psychology (PP) in recent years.

The use of character strengths at work contributes to greater job satisfaction, wellbeing, and performance (Miglianico et al., 2020). It has been identified that using character strengths in job responsibilities causes people to deal better with stress, report higher levels of job satisfaction (Harzer and Ruch, 2015), and feel invigorated and healthier (Pang and Ruch, 2019). The use of character strengths at work contributes to greater employee engagement and job satisfaction (Gander et al., 2012). In this sense, when people use their signature strengths in their daily activities, they are more likely to see their job as a calling or a vocation (Harzer and Ruch, 2016). Identifying the most suitable character strengths for each activity is essential to improving employee performance and satisfaction, for example, nurses who are more aware of interpersonal strengths, perform their tasks better (Harzer and Ruch, 2015). In addition, strengths such as hope contribute to people enrolling in high commitment activities like the U.S. army (Gander et al., 2012).

The use of character strengths in job performance contributes to increasing satisfaction, good performance, and perception of engagement with meaningful work (Littman-Ovadia et al., 2017); in addition, character strengths-bas micro coaching interventions have shown significant effects over time such as performance and wellbeing (Peláez et al., 2020). Both leaders and organizations should encourage workers to use their strengths in daily tasks, for instance, if the leader provides feedback based on employees’ strengths, all parties will be able to see better results than those achieved through traditional feedback (Cameron, 2012). Finally, according to research, organizations must generate a development plan based on employees’ strengths. In this way, they will know that their growth within the organization will depend on the best use of their main skills and competencies.

2.3. Positive environments (A)

The third element considered by the proposal is the positive effect an atmosphere can have on workers, meaning that work environments allow individuals to experience their interaction with colleagues as a support network, generate positive emotions and they can develop and nurture confidence among each other (Baker, 2019).

Workers who have a supportive social network in the organization manage stress better, are less likely to suffer burnout and are less likely to report family and/or work conflict (Jia et al., 2020). Support networks not only serve a functional purpose for the organization by providing informal training and learning but they can also provide love, care, and empathy to co-workers. Work colleagues can listen to the worker’s problems, provide advice, be friends, and from an instrumental perspective, they can be a source of information about the organization likewise (Rousseau et al., 2009). Social support increases affective commitment, and job satisfaction and reduces the intention to quit (Ng and Sorensen, 2008).

The broaden and build theory states that when people experience positive emotion broadens people’s resources in physical, intellectual, and social terms (Fredrickson, 1998, 2001, 2009; Fredrickson and Joiner, 2018). Based on this, the present theoretical BEAT model indicates that positive interactions of workers with their colleagues and leaders allow them to build better personal resources for their professional performance and their personal lives leading them to spirals of well-being (Cameron, 2013).

Positive emotions are linked to greater creativity in life (Fredrickson, 2009; Johnson et al., 2012; Lucas et al., 2009) and at work (Amabile et al., 2005). Living positive emotions endows individuals with more resources, they engage with greater vigor, dedication, and absorption in their tasks and are more successful overall as reported by (Ouweneel et al., 2011). Likewise, living positive emotions and demonstrating joy contribute to better social interaction (Carbelo and Jáuregui, 2006). In this sense, a relevant aspect of emotions is their capacity for contagion and spreading; it is important to point out that when a person lives with positive emotions, people who interact with him or she also perceive such positivity (Michie, 2009). Similarly, workers who live greater flourishing will likely generate a positive effect on their colleagues, leaders, subordinates, customers, and suppliers. Positive emotions and flourishing states lead people to think, feel, and act in such a way that they increase their chances of achieving organizational goals (Lyubomirsky et al., 2005). Finally, positive effects can be the cause of many desirable outcomes, such as increased productivity.

The present BEAT model suggests that there is great relevance in the act of workers manifesting trust in their co-workers and leaders because this contributes to a better interrelation between work teams, which is a key component for the achievement of organizational goals (Tillement et al., 2009). Horizontal trust occurs when people feel that they can share their ideas, emotions, and hopes with their peers within the organization, meanwhile, vertical trust refers to communication with their leaders (Torrente et al., 2012). The willingness of co-workers to help is a paramount element for a person to feel and develop trust with their peers.

When people have strong affective bonds, which can be manifest through vertical and horizontal trust, they are more likely to experience human flourishing. Given the foregoing, employees will likely perform better in their work activities given that they feel recognized by the people they work.

Data suggest that trust between coworkers positively influences collaboration, even within virtual (online) contexts (Alsharo et al., 2017). We trust others when we perceive integrity and benevolence from them (Dutton, 2003). It is important to trust colleagues as they are also a source of informal knowledge about the organization (Tan and Lim, 2009).

In this regard, several studies have pointed out that, concerning job opportunities, interpersonal relationships at work (i.e., work contacts and close friends) are the main source of information for people (Charles-Leija et al., 2018) and that finding employment through friendship ties represents even higher wages (Charles-Leija et al., 2021). Finding employment through friends could also benefit the worker because it might allow easier integration into the new workgroup. In general, workers feel greater satisfaction in their working days if they have a good relationship with their colleagues (Dutton, 2003). Accordingly, social resources, (understood as people’s networks) have a positive effect on the performance of organizations, previous studies have found (Stam et al., 2014). Moreover, positive relationships improve the hormonal, cardiovascular, and immune systems (Cameron, 2012).

In addition, it has been shown that the social, relational component is the one that best explains the meaning workers attribute to their work; such element reflected the fact that workers felt supported by their colleagues and by their leader (Nikolova and Cnossen, 2020).

2.4. Meaningful Work (T)

Life purpose is one of the pillars of well-being (Seligman, 2012). It is perhaps the most complex concept to address, as it can be made up of adverse experiences. Aspects such as a disease, or a difficulty in life can be experiences that, initially, were negative, but when evaluated reflexively it can be seen that they contributed to a life with greater meaning (Baumeister et al., 2013).

Having purpose and meaning allows people to focus more clearly on the steps they need to take to achieve long-term goals. Purpose leads individuals to be more careful in the activities they perform. Purposeful individuals tend to get carried away less by impulses and are thriftier and more diligent (Hill et al., 2016a). In the long term, adults with a greater sense of purpose report greater emotional well-being, lower risk of cognitive declines in old age, and greater longevity (Hill et al., 2016b).

According to Steger (2017), work in addition to being a source of income can also become a source of satisfaction and meaning. Researchers such as (Allan et al., 2016) say that work, as well as the activities that correspond to it, contribute significantly to the meaning of life. People who find meaning in their work live longer, show greater commitment, become less depressed, improve their relationships, and increase their sense of belonging (Bailey et al., 2019; McKnight and Kashdan, 2009).

Steger (2017) defines meaningful work as work in which employees consider it to have meaning and serve a greater purpose. It has become one of the most important ways to understand how a person’s work can contribute to their performance and well-being. Regardless of how they are perceived by society, any work can be meaningful if the person performing it perceives that (Wrzesniewski, 2003).

The level of meaning can be affected by the perception of work and the rewards obtained from it. Work can be perceived as an activity to make money or as a calling (Lysova et al., 2018; Wrzesniewski and Dutton, 2001). On the other hand, for (Steger et al., 2012), meaningful work depends on whether the person perceives the work they do is important to the organization, whether it contributes to improving his/her life, or whether it contributes to a greater good.

People who perceive their work as meaningful report higher levels of engagement (Nikolova and Cnossen, 2020). Thus, finding meaning in work can influence individuals to engage in their tasks with more vigor, dedication, and absorption, that is, that they are fully involved in the task they are carrying out.

There is a resilience component associated with meaningful work. People who have more challenging jobs, even if they do not experience positive emotions, may perceive that their work is more meaningful because, through the adversity involved in their daily activity, they can achieve a higher purpose. Thus, although the work itself is not rewarding, it is a means to reach a greater purpose.

The richness of meaningful work can be seen in the fact that heavy work, involving tiredness and unpleasant activities can be seen as a significant and transcendent job. Examples of this can be nursing, teaching, and cleaning in a hospital. The issue became more relevant in the year 2020 when humanity was experiencing a worldwide pandemic. In that context, in the most severe periods, many economic activities were stopped and only essential activities such as garbage collection, police, supermarkets, and medical and hospital cleaning services were authorized. Empirically, autonomy, competence, and relationships are nearly five times more important to the meaning of work than compensation, benefits, career advancements, job security, and hours worked (Nikolova and Cnossen, 2020).

3. Discussion

From an epistemological point of view, the BEAT model is part of the empiricist tradition, since it is built on theoretical formulations based on evidence, derived from studies on the subject of work well-being as a precursor or result of organizational practices. In addition, it points out the causes and effects of the positive leadership approach, and highlights the personal strengths of workers. It features the effects of positive work and organizational environments and emphasizes the importance that workers transfer to a job in terms of considering they carry out a meaningful work.

While models such as the HERO consider social and organizational resources, as well as leadership as elements that constitute a positive organization, the BEAT model includes some of those aspects but also proposes analyzing and measuring how employees perceive that their work helps them to satisfy their need for meaning or that enables conditions for him or her to perceive that he or she is contributing to society. A positive organization must also take part in satisfying the search for meaning in the work of its collaborators.

This article is aligned with current trends in occupational health research and practices that consider companies as entities that care about aspects beyond income only. In recent years, some proposals have emerged aimed at the creation of companies with purposes beyond economic benefits (Mackey and Sisodia, 2014).

The overall intention is to deliver organizational practices that generate well-being for workers, customers, and communities. In this sense, it has been proposed that educational institutions and productive organizations (i.e., companies) integrate aspects related to the well-being of students and collaborators into their objectives (Adler, 2017; Lombas et al., 2019; McKenna and Biloslavo, 2011; Oades et al., 2011). Examples of the above are Universidad Tecmilenio, the first positive university in the world, and the Geelong Grammar School, which are successful cases in the implementation of wellbeing policies (Seligman and Adler, 2018). In addition, there is evidence from diverse industries increasing the interest for such positive aspects and measurable outcomes (Cameron, 2013; Cameron et al., 2011; Cameron, 2012).

Finding the determinants of people’s well-being in a work context is a key issue for occupational health studies. Measuring physical well-being, the use of strengths, the positive features of work environments, and the meaning at work will be the next methodological challenge, however, Positive Organizational Psychology (POP) has managed to generate a very solid theoretical and methodological framework. The present work showed recent literature related to the subject.

It is by the development of measurable indicators (i.e., scales, questionnaires, etc.) of these aspects regarding organizational wellbeing that it will be possible to identify the pain points and opportunity areas within organizations that are currently putting the worker’s psychosocial well-being at risk.

4. Conclusions

In summary, this article described the four pillars that allow organizations to demonstrate their concern for their workers’ well-being. If companies take care of the elements revised in this paper, they will likely have a greater probability of having committed and productive workers. The theoretical discussion carried out in this manuscript shows the importance of organizational practices. These practices deliver welfare resources to the worker, the activities carried out by the leader to promote positive deviations in their work teams. In addition, the paper highlights the relevance of positive environments between workgroups and the effects finding meaning and significance in day-to-day activities.

This article highlights the relevance of positive organizational practices to having healthy and resilient institutions and organizations that can offer extraordinary results for the members of the organization, as proposed by previous works, like the HERO model (Salanova et al., 2012a, 2016), but also incorporates aspects such as that deemed as meaningful work. One recommendation for organizations is to implement awareness courses on the importance of concepts like compassion, forgiveness, and gratitude within organizations (Cameron, 2012); to integrate workshops on transformational and positive leadership, like the above-mentioned HERO model. Education on positive organization issues can promote the identification of character strengths in workers, which will make them more aware of their abilities and make it easier to use them daily.