1. Introduction

Various psychosocial variables related to work and worker performance have been investigated (Brown, 2008). However, more recently, emphasis has been placed on anomic behaviors concerning worker alienation, which has an evident effect on worker motivation and employment attitudes (Ardila, 1973), leading to a study about organizational civics and its counterpart known as organizational cynicism (Evans et al., 2011). Organizational cynicism can be defined as a set of negative attitudes toward work (Salessi and Omar, 2014b). It covers various conditioning factors and their manifestations associated with several organizational and personnel contextual variables.

Cynicism at work began to be studied in the 1960s with the research of Nieve (Salessi, 2017); it was associated with decreasing enthusiasm and pride in the profession. In that sense, Maslach and Jackson (1981) included cynicism as one of the dimensions of burnout syndrome, which leads to emotional exhaustion in workers, who, due to various work and interpersonal work stressors, develop feelings of depersonalization and a low sense of personal fulfillment.

Brooks and Vane (cited by Salessi, 2017), in the early 1990s, introduced the term “organizational cynicism” as a generalized cynical attitude to the entire organization, which was demonstrated by a lack of conviction in its development. Several investigations have indicated that cynicism at work is more frequent when there is a structural or functional change in the organization (Barton and Ambrosi, 2010; Saravia, 2015; Wanous et al., 2000). While these changes are intended to promote organizational development, they generate distrust in workers, who attempt to sabotage such improvement processes.

Organizational cynicism also refers to a set of dishonest behaviors, lack of integrity of the worker, and negative affectivity towards the organization, which can manifest through openly anomic behaviors such as the express violation of the ethical guidelines of social coexistence in the work context (Formiga et al., 2016), as theft of materials such as machinery or furniture of the company; lies and non-compliance with established norms (Lizarazo and Sánchez, 2016); creation of rumors and gossip that lead to disagreements among collaborators affecting work commitment (Vélez, 2017); or derogatory expressions towards some co-workers or the organization, mediated by feelings of envy (Tomei, 1995).

Therefore, it is necessary to understand that labor activity and all human activities do not occur in a moral vacuum (Manzone, 2019). However, it is impregnated with ethical values towards others and the organization. When certain ethical principles are violated, the trust between the various actors involved in labor, production, and business processes is broken. This way, business ethics and work are increasingly relevant because they affect the worker’s performance and the company’s work environment (Del Castillo and Yamada, 2008) and, more specifically, the productivity of the organization and the conduct of business (Manzone, 2007). Ethics at work is a variable that is part of corporate social responsibility. In this sense, a socially responsible company maintains ethical conduct, both at the organizational level and in the individual behavior of its associates (Maraví et al., 2014). Precisely, the concept of corporate social responsibility has various components that imply care for not only the environment and the impact on the community where companies operate but also the promotion of the health and well-being of workers, and the maintenance of an ethical institutional image, motivated by a solid moral identity rather than merely responding to legal obligations or external pressures (Arias et al., 2016). Thus, corporate behavior directly impacts employees’ perception of their workplace and whether or not certain cynical behaviors are motivated (Aqueveque and Encina, 2010).

It can be said that cynicism and organizational civics are two sides of the same coin because great organizational civism is related to small cynicism and vice versa (Evans et al., 2011). Organizational citizenship is a set of behaviors oriented toward cooperation, commitment, altruism, courtesy, and civic virtue, among others (Loli et al., 2020). It is also associated with proactive work, innovation, and productivity, one of the most investigated issues in recent decades due to its favorable impact on profitability (Salessi and Omar, 2017). Companies increasingly value skills such as those already mentioned: teamwork, ethical behavior, and values related to work (Cabrera, 2017). Likewise, job satisfaction and organizational commitment are associated with civic behaviors at work, favoring a healthy and pleasant labor environment (Shafasawana et al., 2016), while organizational cynicism produces the opposite.

Hence, dishonest behaviors have been related to the socio-economic status of workers (Pascual-Ezama, 2011), so those who receive less salary are more likely to incur cynical and anomic behaviors. In that sense, labor instability and insecurity at work have been associated with the absenteeism of workers at the expense of fulfilling their functions. That related worker attitudes and behaviors can be considered moral offenses while representing negative consequences for the company (León and Morales, 2019). Organizational cynicism has also been related to role ambiguity because organizational citizenship decreases when the worker is less clear (Díaz-Fúnez, 2016).

Along the same lines, it has been seen that when job satisfaction decreases, mediated by chronic work stressors, civic behavior at work decreases too, evidencing the adverse effects of burnout syndrome (Salehi and Gholtash, 2011). The psychological contract is another variable linked to organizational cynicism because when a worker does not feel fulfilled, his/her performance decreases, and job satisfaction increases the possibility of incurring cynical and dishonest behaviors at work (Loli et al., 2017). Organizational cynicism has also been associated with public entities where professional efficacy is reduced, resulting in more cynical behaviors (Marsollier, 2016). Finally, interpersonal relationships at work, particularly those that have a negative connotation between bosses and subordinates, can lead to the appearance of organizational cynicism (Neves, 2012). The latter is fundamental since it has been seen that when workers do not trust the organization’s senior managers, they are more likely to demonstrate cynical behavior (Kim et al., 2009).

Although organizational conditions act as propitiators or triggers of cynical behavior (Salessi, 2011), specific psychological characteristics have been seen to predispose people to cynicism. One of the personality traits associated with improper behavior at work or in other spheres of life is envy (Lersch, 1968). This characteristic usually emerges when a person feels jealous (Salovey, 1991) or perceives they are the victim of unfair treatment (Silver and Sabini, 1978), mediated by a social comparison process (Festinger, 1954). The negativism of the cynical worker is also a characteristic feature since it tends to perceive organizations as unscrupulous entities that exploit workers and lack social responsibility. This pessimistic vision has been positively correlated with the “dark triad of personality,” which encompasses Machiavellianism, egocentrism, and hostility, dimensions that correlate with each other and negatively with job satisfaction (Salessi and Omar, 2018). While the model of the five major personality factors indicates, the responsibility dimension is directly related to organizational citizenship and is negatively related to cynicism (Mahdiuon et al., 2010).

However, among the reasons why organizational cynicism is studied, we can observe that it can be a powerful predictor of internal and external rotation and labor absenteeism (Khan, 2014). It negatively impacts work performance (Omar et al., 2012), is associated with Burnout syndrome, and especially with depersonalization (Salehi and Gholtash, 2011). In addition, it is associated with occupational accidents (Arias, 2016), decreasing of mental health and well-being of workers (Salessi and Omar, 2014a), generation of a very negative corporate image (Formiga et al., 2016), and worse, it can cause a weakening of the authority of the leaders generating chaos in the company’s government system, and its related areas (Salessi, 2017).

The measurement of organizational cynicism began with Kanter and Mirvis (1989, cited by Salessi, 2017), who created an instrument to measure various attitudes in the work environment, including cynicism. Then, this scale was modified in subsequent investigations until it consisted of 12 items and two factors: pessimism or attribution disposition and situational attribution (Wanous et al., 2000). For its part, Brandes et al., (1999) designed a scale of 13 items and three factors known as cognitive organizational cynicism, affective organizational cynicism, and behavioral organizational cynicism, which explained 54.78% of the total variance of the instrument, with adequate levels of reliability (α = .75). This test was called the Organizational Cynic Scale and has been widely used in Latin America by Salessi (2011, 2017) and Salessi and Omar (2014a, 2014b, 2018), after having been adapted and validated in Spanish for the Argentine population.

Salessi and Omar (2014a) reported that it had a structure of 12 items and three factors, according to Brandes et al. (1999; Dean et al., 1998), with adequate adjustment, fit goodness rates obtained by confirmatory factor analysis, and high-reliability rates for each of its dimensions. The cynical idea dimension explained 36.52% of the variance and obtained 11.09% of the total variance Cronbach’s alpha of .86. In addition; there was evidence of divergent validity demonstrated by negative correlations with the variables of organizational trust, organizational commitment, and job satisfaction.

In Peru, there are few studies on this subject. However, a pioneering study was carried out by León (2002), who evaluated envy in professionals in workplaces located in the city of Lima based on previous studies of envy in university students (León and Martell, 1994; León and Moscoso, 1991). León’s work reported a high presence of envy in the work centers, especially among women in his sample. Likewise, a study conducted in Lima found that one of the behavioral profiles of executives included cynical behaviors toward organizational change (Saravia, 2015). More recently, another study, with 435 professionals from Lima, reported that organizational citizenship had a significant positive correlation with the quality of working life, which means those who present low levels of organizational citizenship, that is, greater cynicism, would have a lower quality of life at work (Loli et al., 2020).

As can be seen, there are almost no studies in Peru on organizational cynicism or related variables. These studies do not exist in provincial cities such as Arequipa. One reason for this is the lack of validated instruments to explore these variables; therefore, this study aims to analyze the psychometric properties of the Organizational Cynic Scale (Salessi and Omar, 2014a) in a sample of workers in metropolitan Arequipa.

2. Method

This study is instrumental and provides an assessment of the psychometric properties of the psychological measurement instrument, the cynic scale (Ato et al., 2013).

2.1. Sample

The sample was composed by 710 workers in Arequipa city; 58.59% of the sample was made up of men (n = 416) and 41.40% of women (n = 294). The age of our sample fluctuated between 18 and 60 with a mean of 34.92 years and a standard deviation of ± 8.399 years. The sample was selected in a non-probabilistic way through the technique of intact groups, as all workers came from two labour workplaces in Arequipa city. All workers who decided to participate in the study were evaluated voluntary.

2.2. Instrument

The Organizational Cynic Scale, initially developed by Brandes et al. (1999), includes 13 items distributed across three factors: cognitive organizational cynicism, affective organizational cynicism, and behavioral organizational cynicism. The response scale is Likert type with five alternatives: never (1), rarely (2), sometimes (3), almost always (4), and always (5). For the present study, the 12-item version, validated by Salessi and Omar (2014a) for the Argentine population, was used. These authors confirmed the 3-dimensional structure with adequate values of validity and reliability, obtained by the confirmatory factor analysis and the method of internal consistency with the Cronbach Alpha coefficient, respectively. They also obtained evidence about the validity of the criteria and carried out the idiomatic adaptation through the semantic equivalence method.

2.3. Procedure

First, the corresponding permits were coordinated with the managers of the two selected companies, who provided the facilities for carrying out our study. The assessment was carried out within participants’ work schedules, and workers filled out the instrument during their rest period in an adequate environment provided by the managers. The application of the instruments was individual, and all workers evaluated were informed of the purposes of the study and were guaranteed that their data would remain confidential. Workers who decided to participate in the study signed the informed consent form. The collection of data was made between May and October 2019.

2.4. Data analysis

First, we conducted an exploratory factorial analysis (EFA) of the results from the administration of the Organizational Cynicism Scale of Brandes et al. (1999) and validated by Salessi and Omar (2014a). The instrument was divided into three factors: cynical ideas (items 1, 2, 3, 4, 5), cynical behavior (items 6, 7, 8, 9), and cynical emotions (items 10, 11, 12), according to its reported structure in the Argentine population. From these data, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was carried out to construct validity, using diagonal weighted squares (DWLS) since it will work with ordinal items, taking into account that our sample was large enough (> 200) to allow consistent estimates (Freiberg et al., 2013). Subsequently, the reliability of each factor was analyzed using McDonald’s omega and Cronbach’s alfa coefficients, taking into account the use of ordinal response items (Gadermann et al., 2012). Data was processed using JASP statistical program version 0.13.1 (JASP Team, 2020). First, we conducted an exploratory factorial analysis (EFA) of the results from the administration of the Organizational Cynicism Scale of Brandes et al. (1999) and validated by Salessi and Omar (2014a). The instrument was divided into three factors: cynical ideas (items 1, 2, 3, 4, 5), cynical behaviors (items 6, 7, 8, 9) and cynical emotions (items 10, 11, 12) according to its reported structure in the Argentine population. From these data, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was carried out to analyze construct validity, using diagonal weighted squares (DWLS) since it will work with ordinal items, taking into account that our sample was large enough (> 200) to allow consistent estimates (Freiberg et al., 2013). Subsequently, the reliability of each factor was analyzed using McDonald’s omega and Cronbach´s alfa coefficients, taking into account the use of ordinal response items (Gadermann et al., 2012). Data processing was carried out using JASP statistical program version 0.13.1 (JASP Team, 2020).

3. Results

Descriptive statistics are shown in Table 1. Skewness and kurtosis results did not indicate the need to use nonparametric estimators; however, we decided to use the DWLS estimator because of the Scale’s Likert-type response ratings (Freiberg et al., 2013).

Table 1 Descriptive statistics of items

| Item | Mean | Standard deviation | Skewness | Kurtosis | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2.651 | 1.013 | 0.137 | -0.381 | 1 | 5 |

| 2 | 2.632 | 1.056 | 0.301 | -0.543 | 1 | 5 |

| 3 | 2.531 | 1.185 | 0.388 | -0.733 | 1 | 5 |

| 4 | 2.593 | 1.135 | 0.230 | -0.905 | 1 | 5 |

| 5 | 2.635 | 1.088 | 0.307 | -0.550 | 1 | 5 |

| 6 | 2.486 | 1.082 | 0.325 | -0.632 | 1 | 5 |

| 7 | 2.723 | 1.085 | 0.129 | -0.592 | 1 | 5 |

| 8 | 2.773 | 1.091 | 0.257 | -0.626 | 1 | 5 |

| 9 | 2.411 | 1.075 | 0.593 | -0.245 | 1 | 5 |

| 10 | 2.069 | 1.002 | 0.731 | 0.019 | 1 | 5 |

| 11 | 2.024 | 1.040 | 0.858 | 0.057 | 1 | 5 |

| 12 | 1.906 | 1.028 | 1.152 | 0.881 | 1 | 5 |

Source: Authors’ own elaboration.

To analyze the model adjustment, the χ2/gl, CFI, GFI, RMSEA, and SRMR were used as adjustment goodness-of-fit indices. As for χ2/gl it is understood that values between 1 to 3 are considered a good adjustment (Carmines and Mciver, 1981). Both CFI and GFI must be greater than .9 to demonstrate a good adjustment (Bentler, 1990; Escobedo et al., 2016). As for RMSEA and SRMR, values less than .05 indicate a good adjustment (Hooper et al., 2008). The goodness-of-fit indices obtained were the following: χ2/gl = 1.127, CFI = .999, GFI = .996, RMSEA = .013, SRMR = .037. This indicates there is a good adjustment to the model since all indices were adequate.

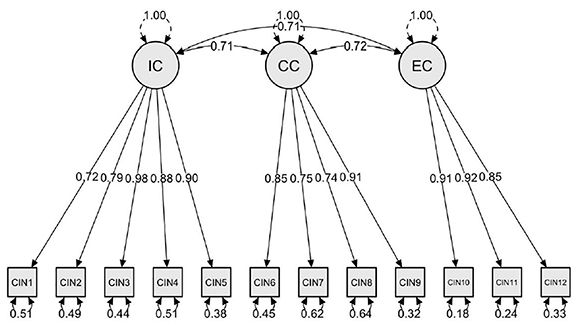

As shown in Figure 1, a CFA was developed based on the model with 3 factors, which obtained factorial loads between .72 and .98. According to Hair et al. (2010), it is an ideal result by having greater factor load to .7. In addition, the covariances between the factors were significant, which demonstrates a high relationship between them.

In the same way, as can be seen in Table 2, the reliability obtained from the factors was adequate: cynical ideas (ω = .886, α = .883), cynical behavior (ω = .841, α = .841) and emotion Cynics (ω = .907, α = .906), as rates were obtained. Therefore, it is concluded Organizational Cynicism Scale is valid and reliable, confirming the internal structure of the three factors. Likewise, in this table, the descriptive values of average, standard deviation, skewness, kurtosis, and minimum and maximum scores of each factor are also observed. Moreover, a 3-level qualification scale: high, medium, and low, was developed.

Table 2 Descriptive statistics of factors and reliability

| Cynical ideas | Cynical behaviors | Cynical emotions | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 13.042 | 10.393 | 5.999 |

| Standard deviation | 4.529 | 3.565 | 2.817 |

| Skewness | 0.264 | 0.272 | 0.918 |

| Kurtosis | -0.464 | -0.359 | 0.444 |

| Minimum | 5 | 4 | 3 |

| Maximum | 25 | 20 | 15 |

| Reliability | ω= .886, α= .883 | ω= .841, α= .841 | ω= .907, α= .906 |

| Percentiles | |||

| High level (76 - 100) | 18 - 25 | 14 - 20 | 8 - 15 |

| Medium level (26 - 75) | 11 - 17 | 9 - 13 | 4 - 7 |

| Low level (0 - 25) | 0 - 10 | 0 - 8 | 0 - 3 |

Source: Authors’ own elaboration.

4. Discussion

Organizational cynicism was associated with alienation at work (Ardila, 1973). It has recently been subject to systematic study in organizational psychology, linking with other classical organizational variables, such as job satisfaction, organizational climate, worker performance, etc. (Salessi, 2011). The importance of organizational cynicism is clear, as it strongly predicts morality and productivity at work. These aspects have also been gaining more attention from the academic and business community at a global level (Manzone, 2007).

Despite this, in Peru, few studies have focused directly on organizational cynicism or indirectly through related variables such as envy at work (León, 2002) or organizational citizenship (Loli et al., 2020). The main reason for the limited research on organizational cynicism is the lack of duly validated instruments that can be used to evaluate this variable. In that sense, an instrumental study was designed to analyze the psychometric properties of the Organizational Cynic Scale, which involved evaluating 710 workers in Arequipa City.

Our results confirmed the 3-dimensional structure of the Organizational Cynic Scale, validated by Salessi and Omar (2014a) in Argentina, with adequate factor load and goodness-of-fit index. The cynical idea factor comprised items 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5, with optimal Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega coefficients reliability rates. This dimension refers to negative beliefs about boss practices, highlighting the incongruity between what is requested and what is done. The cynical behavior factor comprised items 6, 7, 8, and 9, and as in the previous case, optimal reliability rates were obtained. This dimension values the creation of rumors, negative criticism, and specific behaviors of complicity that have been mentioned as typical of organizational cynicism (Rosnow, 1980, 1991; Salessi, 2017). Finally, the cynical emotion factor comprised items 10, 11, and 12, with high-reliability rates of Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega coefficients. This dimension mentions emotions of anger, tension, and discomfort when workers think about their companies, which have been linked to the deterioration of mental health at work (Salessi and Omar, 2014b).

Based on those mentioned above, the Organizational Cynic Scale has adequate rates of validity and reliability, confirming the internal structure reported by Salessi and Omar (2014a). Since percentiles for their qualification have been estimated, it can be used to evaluate the cynicism of workers in organizational contexts in Arequipa and Peru, but also in Latin America. However, exploring its psychometric properties further is suggested, considering some comparison criteria such as the gender of workers or whether they are working in the public or private sector. This aspect is due to some studies reporting that, while women are less cynical (Formiga et al., 2016), others found no differences in organizational cynicism between men and women. However, they may manifest cynicism differently (Salessi, 2011). Likewise, some research indicates that in the public sector, there is a higher incidence of cynicism (Marsollier, 2016), while others point out that the differences are not significant (Loli et al., 2020).

In our study, it has not been possible to make these comparisons due to the lack of equivalence between groups and the type of sampling used, reducing the generalization possibilities. Considering that it is the first study on organizational cynicism in our city, it constitutes a starting point for future investigations that allow analyzing factorial invariance, convergent, divergent, and predictive validity, among others.

In addition, it would be convenient to work on a modified version of the Organizational Cynic Scale because the content of the items and their underlying structure may not reflect the wide range of manifestations of organizational cynicism, such as sabotage, errors regarding coalitions, and power groups, lowering the pace of work, among others (Saravia, 2015). Likewise, more studies on organizational cynicism should be carried out concerning variables such as personality (León, 2017) and values (Sinha et al., 1993) in order to promote an improvement in the performance of labor, and work well-being, based on organizational behavior (Bravo et al., 2020).

In summary, the Organizational Cynic Scale is a valid and reliable instrument, which is useful in the regional, national, and Latin American organizational field since previous studies in other Latin American countries have also confirmed its psychometric properties (Salessi, 2017; Salessi and Omar, 2014a, 2018). Therefore, we concluded Organizational Cynic Scale has adequate psychometric properties, and its use in companies, industries, and labor organizations is recommended.