1. Introduction

Several studies have addressed motivation towards learning a foreign language, focusing on the effects of intrinsic motivation (Gamlo, 2019; Namaziandost et al., 2019; Lamb and Arisandy, 2020) and extrinsic motivation (Escobar et al., 2019; Liu, 2020) on language learning. These studies have utilized methodologies based on digital tools such as applications, social networks, or specialized platforms. However, all of these studies are centered from the perspective of education and pedagogy, rather than from the viewpoint of educational marketing, where marketing actions by providers of foreign language teaching services directly influence motivated behaviors toward consumption.

Motivation for learning can be defined as an individual’s active behavior driven by the desire to learn or acquire new knowledge. It becomes evident that motivation influences thinking, and consequently, learning outcomes (Kukar-Kinney et al., 2016). In this sense, the actual possibility of an individual achieving their goals, and knowing how to act to successfully face tasks and problems, plays a crucial role in managing prior knowledge and ideas about the content to be learned, its meaning, and utility (Escobar et al., 2019).

In this context, motivations for second language learning can be directed by personal and social factors, considering that proficiency in another language, particularly English, is in high demand in the professional and academic world today (Ryan and Deci, 2000). Although not the most spoken language globally, English is the most sought-after when it comes to job opportunities since its knowledge is essential for the workplace. High-paying jobs often require a B2 or C1 level of proficiency. Among the professions that demand this level of proficiency are tourism, finance, and everything related to technology (Rodríguez et al., 2021).

In this regard, there is a surge in the emergence of online platforms offering services for second language learning. These platforms conduct aggressive marketing campaigns both in traditional media and in the digital realm. The perspective of online or digital learning has shifted due to the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown (Vázquez-Martínez et al., 2021). This has led to the rise of influencers and content creators on social media platforms to facilitate second language learning (Suryasa et al., 2017; Izquierdo and Gallardo, 2020).

Hence, the objective of this research is to analyze whether extrinsic and intrinsic motivation is influenced by advertising actions and the factors considered when purchasing online language courses among individuals aged 18 to 40 in the city of Bogotá. This type of study has not been extensively conducted in the Latin American context and contributes to a better understanding of consumption behavior and motivations in the digital context.

2. Consumer Motivation

Motivation towards consumption is an effect caused by need, which is the absence or lack of something, generating a state of tension that leads to actions in the pursuit of fulfilling that deficiency (Maslow and Lewis, 1987). It is an impulse to do things where the execution of the task itself serves as the reward. According to the theory proposed by Deci and Ryan (1985), there are several stages through which a person can transition from a phase where motivation is purely external to a final stage where they can integrate and embrace the purpose of their activity as their own.

2.1. Intrinsic Motivation

The theory of intrinsic motivation is based on human needs such as hunger, thirst, and basic psychological needs. It is related to social psychology and the self-determination theory, which provides a framework for the study of motivation and suggests that people achieve self-determination when they satisfy their needs for competence, relatedness, and autonomy (Gómez, 2021). Once satisfaction of all these needs is achieved, humans begin to emerge from this self-determination created by themselves without feeling that it is based on the fulfillment of responsibilities (Deci and Ryan, 2012).

The main objective of self-determination theory is to understand human behavior in such a way that this knowledge can be generalized to all situations that humans in all cultures may encounter, affecting any area, sphere, or vital domain (Ryan and Deci, 2000). In this sense, the theory focuses on motivation as the primary element to analyze, assessing the existence of a pool of energy generated by different human needs that will later acquire a direction or orientation toward satisfying those needs. Therefore, it exerts an inherent tendency to seek novelty and challenge, to extend and exercise one’s own capabilities, to explore, and to learn (Stover et al., 2017). In other words, those who decide to learn another language do so because of its relevance in their professional lives (Butz and Stupnisky, 2017). Other studies indicate that the motives driving bilingual individuals to study another language are extrinsic, although it is important to note that knowing and improving in the language can lead to intrinsically motivating gratifying emotions (Zardain, 2015; Lin et al., 2017).

2.2. Extrinsic Motivation

Extrinsic motivation comes from the external environment and serves as a driving force to accomplish something (Ryan and Deci, 2000), where social rewards are the result of this type of motivation, and all kinds of emotions related to outcomes are supposed to influence extrinsic motivation. Within these outcome-related emotions, prospective and retrospective emotions are distinguished (Deci and Ryan, 2012). Prospective emotions are those immediately and directly linked to task outcomes, while retrospective emotions are reactions to the task itself that also interfere with them, reinforcing motivation towards the outcome, such as pride or happiness in response to success. Emotional intelligence is crucial in this regard as it teaches how to handle situations that hinder the need for learning (Alonso and Pino-Juste, 2014).

In the context of learning another language, this study aims to understand extrinsic motivation towards recognition and status due to proficiency in a foreign language. However, most studies focus on the context offered by the online course itself, such as methodology, content, and resources (Anders, 2018; Sergis et al., 2018; Gómez, 2021). In this sense, the external context that can motivate a student to take such courses from a social or social consequence perspective is a field that has not been extensively explored and requires development from a consumption perspective for a better understanding of such consumption (Liu, 2020).

2.3. Aspects for Hiring an Online Language Course

Several studies focus on examining the aspects considered when purchasing services from an online platform. However, from the perspective of foreign language learning, some of these aspects are viewed from the platform’s standpoint, such as ease of platform use (Fan et al., 2021), flexibility in methodology (Huang et al., 2017), and content quality (Mohammadi, 2015). Additionally, the use of digital tools to facilitate interaction with students and technological learning resources (Pikhart and Kimova, 2020) is also considered.

Other studies concentrate on factors like quality and the degree of satisfaction (Fan et al., 2021). These factors are grounded in perceived trust and utility since they relate to performance expectations and the level of learning, such as versatility in mastering a second language. This is why a trial or demonstration class is a way to alleviate uncertainty and plays a positive role in the intention to purchase (Chen et al., 2021). However, for others, social influence and aspects related to interaction with the teacher and other students become crucial because methodologies with exclusivity in guidance and teaching are preferred (Zhu et al., 2020).

2.4. Advertising Actions Influencing the Purchase of an Online Language Course

Educational marketing involves developing strategic actions to benefit brands in the education sector (Kotler and Fox, 1985). Therefore, online language learning platforms adopt these communication strategies to generate interest in this method of learning a foreign language, highlighting the latent needs resulting from not having proficiency in a foreign language.

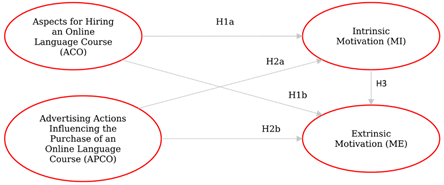

In this sense, brand actions such as website design, commercial activities, brand reputation (Cristancho et al., 2019), are relevant in the educational context and evoke situations where both personal and social contexts can become encouraging agents for encouraging the consumption of these services. Commercials featuring the use of a foreign language (Planken et al., 2010; van Hooft et al., 2017) or invoking situations where proficiency in this language is essential exert influence on motivation for consumption. In this regard, Figure 1 illustrates the proposed theoretical model with its respective hypotheses.

H1a: Aspects for purchasing an online course influence intrinsic motivation to buy an online language course.

H1b: Aspects for purchasing an online course influence extrinsic motivation to buy an online language course.

H2a: Advertising actions of online language course platforms influence intrinsic motivation to buy an online language course.

H2b: Advertising actions of online language course platforms influence extrinsic motivation to buy an online language course.

H3: Intrinsic motivation influences extrinsic motivation to buy an online language course.

3. Methodology

This research is descriptive in nature with a quantitative approach as it aims to analyze the influence between leisure needs, advertising actions, and the factors considered when acquiring an online language course on intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. The target group consisted of men and women aged 18 to 40 in the city of Bogotá, who expressed an intention to take a course for learning a foreign language in the digital context. A non-probabilistic convenience sampling method was used, resulting in 555 participants.

As a data collection instrument, a digital survey was used, divided into two parts. The first part included seven items to describe the respondents’ demographic information. The second part comprised 33 items with Likert scale responses (1= strongly disagree, 5= strongly agree). To assess intrinsic motivation, questions related to personal needs for learning a foreign language were used (e.g., “It improves my quality of life”). For extrinsic motivation, questions involving the social context in terms of recognition for proficiency in a foreign language were used (e.g., “Others will perceive me as successful”).

For brand advertising actions and factors for purchasing an online language course, a pilot study (n=375) was conducted, identifying that among the most representative factors for buying an online language course were the learning methodology, the degree of class personalization, the ease of managing one’s own schedule, payment convenience, price, user reviews, seller contact method, and the possibility of a free trial. Regarding brand advertising actions, aspects such as brand reputation, credibility, highlighting the benefits of learning a second language, and price-related actions such as discounts were found to be the most accepted.

Data analysis was performed using SPSS v26 for descriptive analysis, exploratory factor analysis (EFA), and Cronbach’s Alpha calculation. Amos v24 was used for confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), and hypothesis testing was conducted through structural equation modeling methodology.

4. Results

The population that participated in the study can be characterized by age groups, with individuals aged 18 to 25 years (n=278, 50.1%) and 26 to 40 years (n=277, 49.9%). The majority of participants were female (n=309, 55.7%) as opposed to male (n=246, 44.3%). They were distributed across socioeconomic strata as follows: 1 (n=16, 2.9%), 2 (n=222, 40.0%), 3 (n=272, 49.0%), 4 (n=42, 7.6%), 5 (n=2, 0.4%), and 6 (n=1, 0.2%).

Regarding income, most participants fell within the range of 1 to 2 SMMLV (n=249, 44.9%), followed by less than 1 SMMLV (n=172, 31.2%), and 2 to 4 SMMLV (n=132, 23.9%). In terms of occupation, the majority were employed (n=218, 39.3%), followed by those who both studied and worked simultaneously (n=119, 21.4%), those who were solely students (n=122, 22%), and those who were self-employed or had other occupations (n=96, 17.4%).

For the educational level, most had completed a technical and/or technological degree (n=227, 40.9%), while a portion had only completed primary or secondary education (n=151, 27.2%), followed by those with a bachelor’s degree (n=146, 26.3%), and postgraduate degrees (n=31, 5.6%). Lastly, as for the preferred foreign language for learning, it was determined that English was the most predominant choice (n=454, 81.9%), followed by French (n=60, 10.8%), and other languages (n=41, 7.3%).

Next, an EFA (Exploratory Factor Analysis) was conducted to validate the instrument’s dimensionality. This was achieved using the Principal Component Analysis method with Varimax rotation. The goodness-of-fit indicators for the model were satisfactory, both for the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure (KMO=0.961) and for Bartlett’s test of sphericity (x^2=17998; df=528; p<=0.0001). The model converged into 4 factors, explaining 71.39% of the variance. However, the initial result produced 4 variables (V19, V20, V21, and V30) with factor loadings below 0.7, so they were removed from the study (citation). When CFA (Confirmatory Factor Analysis) was applied, all variables obtained factor loadings greater than 0.7.

In order to assess the internal consistency of each construct, an analysis based on Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient was conducted, yielding satisfactory results for each factor with values exceeding 0.88. These results can be observed in Table 1.

Table 1 Factor Loadings and Cronbach’s Alpha

| Construct | Variable | Factor Loading | Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intrinsic Motivation (MI) | V1 | 0.903 | 0.975 |

| V2 | 0.893 | ||

| V3 | 0.872 | ||

| V4 | 0.907 | ||

| V5 | 0.86 | ||

| V6 | 0.842 | ||

| V7 | 0.856 | ||

| V8 | 0.869 | ||

| V9 | 0.878 | ||

| V10 | 0.802 | ||

| V11 | 0.889 | ||

| V12 | 0.808 | ||

| V13 | 0.83 | ||

| V14 | 0.805 | ||

| Extrinsic Motivation (ME) | V33 | 0.939 | 0.912 |

| V32 | 0.893 | ||

| Advertising Actions Influencing the Purchase of an Online Language Course (APCO) | V18 | 0.826 | 0.873 |

| V17 | 0.785 | ||

| V16 | 0.814 | ||

| V15 | 0.743 | ||

| Aspects for Hiring an Online Language Course (ACO) | V22 | 0.89 | 0.938 |

| V23 | 0.871 | ||

| V24 | 0.842 | ||

| V25 | 0.852 | ||

| V26 | 0.816 | ||

| V27 | 0.707 | ||

| V28 | 0.755 | ||

| V29 | 0.755 |

Source: Authors’ own elaboration.

In Table 2, the results of indicators for convergent validity are observed, and it is noted that for each construct, the proposed Composite Reliability (CR) index achieved results above 0.7, and the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) exceeded 0.5, which are considered satisfactory (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). As for discriminant validity, it is observed that the Maximum Shared Variance (MSV) had values lower than AVE, thus meeting the criteria proposed by Hair et al. (2012). Additionally, it is noted that the square root of AVE is higher than the correlations between constructs (Fornell and Larcker, 1981).

Table 2 Convergent and Discriminant Validity

| CR | AVE | MSV | MaxR(H) | ACO | APCO | ME | MI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACO | 0.94 | 0.661 | 0.262 | 0.947 | 0.813 | |||

| APCO | 0.873 | 0.632 | 0.409 | 0.878 | 0.487*** | 0.795 | ||

| ME | 0.913 | 0.84 | 0.58 | 0.92 | 0.398*** | 0.461*** | 0.917 | |

| MI | 0.975 | 0.738 | 0.58 | 0.977 | 0.512*** | 0.443*** | 0.761*** | 0.859 |

Note: ***=p<0.001.

Source: Authors’ own elaboration.

For the development of the causal model, the bootstrapping technique with 2000 subsamples was used to test the proposed hypotheses. This technique allows projecting more samples from the initial one in order to test hypotheses at a descriptive level (Ledesma, 2008). The absolute fit indices (x^2=786.0, p<0.001; CMIN/DF=2.629, and RMSEA=0.054), incremental fit indices (NFI=0.956; TLI=0.962; CFI=0.972), and parsimony fit indices (PNFI=0.708; PCFI=0.72) are satisfactory according to the criteria proposed by McDonald and Ho (2002), Hooper et al. (2008), and Byrne (2013).

In the resulting causal model, it is observed that the coefficient of determination for MI (R^2=0.602) is higher than that for ME (R^2=0.314). Additionally, it is noted that the rejected hypothesis is H1b (p<0.198), meaning that the factors considered when purchasing an online language course do not influence extrinsic motivation. However, the rest of the proposed hypotheses were accepted, as shown in Table 3. Regarding indirect effects, it is observed that the relationships between APCO and MI towards ME are complete, as they obtained satisfactory levels of significance (P<0.001). Therefore, extrinsic motivation is mediated by intrinsic motivation when it arises either from advertising actions. However, when this relationship starts with the factors considered when acquiring an online language course and is mediated by intrinsic motivation, the mediation is partial because when evaluating H1b, it was rejected.

Table 3 Hypothesis Testing

| Hypothesis | Path | S.E. | C.R. | P | Result | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a | ACO | → | MI | 0,385 | 0,07 | 8,486 | *** | Accepted |

| H1b | ACO | → | ME | -0,051 | 0,058 | -1,289 | 0,198 | Rejected |

| H2a | APCO | → | MI | 0,261 | 0,065 | 5,54 | *** | Accepted |

| H2b | APCO | → | ME | 0,178 | 0,052 | 4,433 | *** | Accepted |

| H3 | MI | → | ME | 0,707 | 0,039 | 17,32 | *** | Accepted |

Note: ***=p<0.001.

Source: Authors’ own elaboration.

5. Discussion

Studies addressing the relationship between both intrinsic and extrinsic motivation have traditionally been approached from the perspectives of pedagogy and education. However, this study provides a different perspective from the context of marketing. In this regard, the results align with what Ryan and Deci (2000) proposed, as motivations for learning a second language through an online platform stem from both intrinsic and extrinsic motivations.

Thus, the findings are consistent with the propositions made by Escobar et al. (2019), who stated that aspects associated with intrinsic motivation, such as improving one’s professional position, living abroad, and being able to communicate with others, are relevant factors influencing the decision to take a language course. These factors can be influenced by the aspect’s consumers consider when acquiring a course, which supports the acceptance of hypothesis H1a and aligns with what Chen et al. (2021) proposed. On the other hand, the brand’s actions in terms of its communication directly affect both intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. This communication becomes an element that evokes trust and security by highlighting the platform’s attributes. When consumers evaluate these attributes, they identify that the platform offers what they are looking for, motivating them and increasing the likelihood of consumption. This is evident through the acceptance of hypotheses H2a and H2b, and it is consistent with studies conducted by Zhu et al. (2020) and Fan et al. (2021).

Finally, it can be observed that intrinsic motivation is viewed from the perspective of retrospective emotions, where individual aspects related to learning capabilities, derived from the benefits offered by the platform in terms of methodology and flexibility, as well as social recognition, generate a feedback loop that fuels motivation for how they want to be seen by others. Therefore, hypothesis H3 is accepted and aligns with the theory proposed by Deci and Ryan (2012).

6. Conclusions

Motivation to learn a foreign language through an online platform is directly related to how other people perceive and think of individuals when they acquire this competence. Learning a second language not only allows individuals to expand their job opportunities but also to feel that they have overcome challenges, with others viewing them as role models and, in a way, as a source of motivation to succeed.

In this sense, it was evident that a strategy for learning a foreign language using virtual platforms should be aligned with the motivations of potential learners. To achieve this, it is necessary to innovate and apply methodologies based on didactic models (Yu, 2022) and virtual games (Jurkovič, 2019; Cornellà et al., 2020). This approach will make learning more engaging and enable students to feel proactive in their learning journey (Suryasa et al., 2017).

Motivation for learning a foreign language is crucial in today’s society as it enables individuals to build and rebuild knowledge, leading to communication skills and habits. This, in turn, opens doors to new businesses and cultures (Barak et al., 2016). With motivation being bidimensional (intrinsic and extrinsic), it serves as a tool for understanding personal and knowledge-related relationships, attitudes (Zheng et al., 2018), and global knowledge. Most participants in this study chose to learn this language for career-related reasons, as it has become a necessary tool in the modern workplace.

Lastly, it’s worth mentioning and recommending that this research could pave the way for further investigations related to motivation and interest in learning on online platforms from a marketing perspective. This could lead to the development of theories that explain if this effect is similar in different consumption contexts, such as higher education, and if other variables such as attitudes and the impact of social media communication can be precursors to consumption.