1. Introduction

The present work addresses an unspoken deficiency of the literature on supply chain management, namely, the lack of a strategic characterization of the dairy Supply Chain (SC). This, in turn, determines the implicit value of the paper and frames its main objective, which is to identify the strategic context of this important chain. This is attained through the methodology introduced by (García-Caceres et al., 2014) and its specific objectives: evaluation of the global and national production of the dairy SC, identification and description of its links and stages, assessment of the value added by its agents and links, and detailed analysis of its performance specificities. This descriptive basis of the dairy SC is expected to facilitate decision-making by its agents and stakeholders.

The paper is structured as follows: after a thorough literature review, the methodology (García-Cáceres et al., 2014) is developed, and then conclusions are drawn.

2. Literature review

The global economy of agribusiness commodities is increasingly demanding a shift in agricultural practices toward organic systems (Nicholas et al., 2014). The European Union has led the way as to the implementation of environmental policies, which pose significant challenges for their suppliers, especially those non-European ones who are not sufficiently familiar with green production culture. Thus, the need for sustainable practices in the food SC is currently intensifying, especially in regard to the reduction of energy and chemical agents, among many other competitive requirements. This has certainly put the food industry under intense pressure (Glover et al., 2014).

The dairy SC is the set of agents and stakeholders that are responsible for satisfying the final customer of the commodity and its derivatives. For such purposes, these organizations operate according to their specific corporate missions.

The food SC and, specifically, the dairy product SC are characterized by data recording, information flow and productive process singularities, which generate SC transparency across agents (Trienekens et al., 2012). In recent years, the literature has turned its attention to production planning in this chain (Sel and Bilgen, 2015), which is frequently affected by problems related to input supply, elevated product demand, expiration dates and changes in demand (Guarnaschelli et al., 2020).

Regarding the conduction of case studies on this topic, Gómez-Verjel et al. (2018) analyzed three dairy product trading companies in the Caribbean region, namely, Proleca, WMA and Frappy. By developing an optimization model, they introduced a series of possible solutions for the difficulties experienced by these companies, which ranged from adverse weather conditions to social manifestations, all of which affected the different stages of the chain. In turn, and supported by a stochastic two-stage mixed-integer linear model, Guarnaschelli et al. (2020) studied integrated production and distribution planning in dairy SCs. Likewise, Mandolesi et al. (2015) implemented Stephenson’s Q methodology to identify innovation opportunities in dairy SCs, thus reducing inputs. Finally, in a related work, López-Ramírez and García-Cáceres (2020) characterized beef SC.

3. Methodology

Proposed by García-Cáceres et al. (2014), the methodology applied in the present work is the most recent version of a generic SC strategic characterization technique. As such, it has allowed the characterization of some important agricultural SCs. At first, it was applied to coffee (García-Cáceres and Olaya, 2006), followed by oil palm (García-Cáceres et al., 2013), cocoa (García-Cáceres et al., 2014) and potato (García-Cáceres et al., 2018), among others. This methodology seeks to facilitate SC decision making at the strategic level (García-Cáceres and Escobar, 2016), which satisfies an important SC management need that had been previously identified by Riopel et al. (2005).

It comprises the following steps:

Evaluation of dairy SC production at the national and global scales.

Identification and description of links and stages.

Description of agents and links of the dairy SC.

Diagnosis and conclusions of the SC characterization.

The application of this methodology to the present work is detailed below.

4. Development

4.1. Evaluation of dairy SC production at the national and global scales

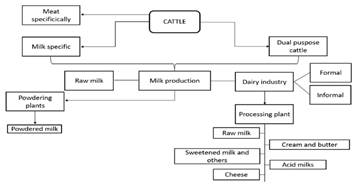

At this stage, the object of study is characterized strategically in a global market context, emphasizing the specific conditions of the Colombian dairy SC. Based on the different products supplied by this chain, Figure 1 presents its characterization according to the methodology applied in this work:

As can be observed in Figure 1, the dairy SC products can be classified into three main categories: raw milk, processed milk, and milk derivatives. Several alternatives can be found in the industrial processing of milk, resulting in a diversity of derivatives: pasteurized milk, concentrated milk (be it powdered or liquid) and acid milks, among others. In addition, some of these processes require additives, including rennet (to separate whey during cheese production) or butter and sugar, for the production of derivatives such as milk caramel cream, among others.

4.1.1. Global market.

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Alimentación y la Agricultura [FAO], 2019), in 2018, milk production around the world was distributed as follows: 81% corresponded to cow milk, 15% to buffalo milk and 4% to goat and sheep milk. In 2019, bovine milk production reached 852 million tons, of which the largest fraction was produced by India.

In recent years, global trade has been shifting toward green markets and vegan diets. Although this situation has slowed down the demand for dairy products, this supply chain is characterized by resilience. By 2020, indeed, it not only had undergone a commercial increase but was also one of the sectors least affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Procolombia (2018) explains that the national dairy industry is currently on the rise, ranking fourth among American milk producers since 2015. According to Colombian Federation of Livestock Breeders (Federación Nacional de Ganaderos [FEDEGAN] 2021a), by 2019, Brazil was the largest livestock producer in America, with 214,659,840 cattle heads, followed by the United States with 94,804,700, Argentina (54,460,799), and Mexico (35,224,960) (Table 1). In turn, Colombia went from having 22,782,257 cattle heads in 2015 to 28,832,858 in 2019.

Table 1 Latin American Dairy Production

| Production | Country |

|---|---|

| 35,890,280 l | Brazil |

| 12,275,865 l | Mexico |

| 10,339,935 l | Argentina |

| 7,184,000 l | Colombia |

Source: FEDEGAN (2021b).

The top 5 milk producers in the world are the European Union, with 148,445,440 l, the United States (99,056,527 l), India (90,000,000 l), Brazil (35,890,280 l) and China (32,444,339 l), together accounting for 58% of the world’s milk production.

4.1.2. Local Market.

During the fourth trimester of 2019, the Colombian Gross Domestic Product (GDP) resulting from cropping, cattle growing, hunting, forestry and fishing increased by 1.5%. Likewise, in the first trimester of 2020, this same figure underwent a 6.8% rise. In turn, the agricultural sector accounted for 6.8% of the national GDP in 2021 (FEDEGAN, 2021b). In turn, the cattle growing sector accounted for 1.6% of the national GDP and 25.2% of the agricultural GDP in 2020. For its part, the dairy sector accounted for 36.7% of the cattle growing sector in the same year National Administrative Department of Statistics (Departamento Nacional de Estadística [DANE] 2020).

In December 2019, milk and dairy product imports reached 3,919 tons, where as in the same period of 2020, they reached 2,754 tons. These figures exhibited variations during the first semester of 2020, reaching a peak in January, with 21,108 tons, and a drop in the second semester (Table 2).

Table 2 Colombian milk and dairy product imports from 2020 to August 2021

| Month | 2020/tons | 2021/tons | Month | 2020/tons | 2021 (tons) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| January | 21,108 | 15,385 | July | 6,993 | 3,752 |

| February | 3,299 | 3,289 | August | 5,662 | 4,123 |

| March | 5,997 | 2,755 | September | 4,611 | N.D. |

| April | 6,396 | 3,418 | October | 3,079 | N.D. |

| May | 5,334 | 3,491 | November | 2,427 | N.D. |

| June | 6,003 | 2,264 | December | 2,754 | N.D. |

Source: FEDEGAN (2021c).

In Colombia, the price of imported milk is mainly governed by USP quotas, together with currency exchange rates and international prices. As a consequence, in 2021, domestic demand was largely supplied by imports (Table 3).

Table 3 Main dairy products imported to Colombia by August 2021

| Products | Net Tons | CIF value (thousand US$) | Participation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Skimed milk powder | 20,913 | 53,581 | 49 |

| Whole milk powder | 9,007 | 29,915 | 27 |

| Fresh Cheese | 1,538 | 8,760 | 8 |

| Other cheeses | 1,100 | 6,398 | 6 |

| Whey | 4,794 | 5,308 | 5 |

| Grated or powdered cheese | 455 | 3,345 | 3 |

| Processed cheese | 399 | 1,818 | 2 |

| Yogurt | 81 | 331 | 0.30 |

| Blue cheese | 48 | 275 | 0.20 |

| Other milks containing added sugar | 75 | 233 | 0.20 |

| Butter | 21 | 103 | 0.10 |

| Other milks and creams | 15 | 75 | 0.07 |

| Whole liquid milk | 19 | 36 | 0.03 |

| Condensed milk | 9 | 26 | 0.02 |

| Anhydrous milk fat (“butteroil”) | 2 | 19 | 0.02 |

| Liquid milk containing more than 10% fat by weight | 0.03 | 0.2 | 0.00000200 |

| Total | 38,477 | 110,223 | 100 |

Source: DANE 2021 Taken from FEDEGAN (2021c).

Colombia exports dairy products to approximately 45 countries (Procolombia, 2018), including Bangladesh (whole milk), Costa Rica (milk caramel cream and condensed milk), the United States (milk, milk cream, condensed milk, yogurt, cheese), Hong Kong (cheese, condensed milk, powdered milk, butter, liquid milk, dairy drinks, cream and ice cream), Panama (mozzarella cheese, grated or powdered cheese of any kind for industrial use, processed cheese, blue cheese, cheddar cheese, cheddar cheese for industrial use, Muenster cheese, other matured cheese types, and milk caramel cream), the Eurasian Economic Union (Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, among others), Canada, Cuba, India, Peru, Armenia and Chile (milk and dairy products). Table 4 shows Colombian dairy product exports (FEDEGAN, 2021c).

Table 4 Colombian milk and dairy derivative exports from 2020 to September 2021

| Month | 2020/tons | 2021/tons | Month | 2020/tons | 2021/ton |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| January | 193 | 524 | July | 225 | 733 |

| February | 196 | 300 | August | 373 | 905 |

| March | 235 | 715 | September | 273 | 500 |

| April | 266 | 942 | October | 495 | N.D. |

| May | 411 | 514 | November | 678 | N.D. |

| June | 334 | 780 | December | 924 | N.D. |

Source: FEDEGAN (2021c).

Colombian exports showed significant variability from January 2019 to September 2021, ranging from 193 to 942 tons. This results from the combined action of different factors, namely, export credits, domestic and international price conditions, and contractual commitments.

In 2020, on-farm consumption accounted for 7% of gross milk production, which ranged from 500 to 525 million liters Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (Ministerio de Agricultura y Desarrollo Rural [MinAgricultura], 2020a).

Colombia is a cattle-growing country and, as such, also a milk producer. In addition, the country is favored by natural pastures and good land availability for this activity. Regarding the distribution of milk production across Colombian departments, Antioquia and Cundinamarca are the largest producers, accounting for 34% of national production. Nonetheless, there is significant milk production in the other eight departments of the country (Table 5).

Table 5 Colombian milk production percentages by department in 2019

| Department | Percentage (%) | Liters/day | Department | Percentage (%) | Liters/day |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antioquia | 19 | 3,826,139 | Nariño | 4 | 825.459 |

| Cundinamarca | 15 | 3,014,402 | Meta | 4 | 813.459 |

| Cordoba | 7 | 1,373,543 | Santander | 3 | 813.830 |

| Boyaca | 6 | 1,207,998 | Sucre | 3 | 651.600 |

| Magdalena | 5 | 946,963 | Other departments | 29 | 5.947.068 |

| Cesar | 5 | 923,623 |

Source: USP data, according to DANE and ENA Taken from FEDEGAN (2019a).

Similarly, different cattle types dominate this activity across Colombian departments. While Cundinamarca and Antioquia have specialized in dairy cattle, Nariño and Cordoba tend to grow dual-purpose cattle. The other cattle growing departments of the country are also significant milk producers, mainly due to the size of their cattle population.

According to FEDEGAN (2021b), dairy production in Colombia generates approximately 138,542 jobs. This results from the manufacturing of a variety of industrial products, namely, liquid milks (48%), powdered milk (17%), cheese (20%), fermented milks (8%), and other products (6%) (MinAgricultura, 2020b).

The production of these derivatives is usually preceded by two major processes: milking and pasteurization.

In a general sense, the industrialization of milk starts from insemination, weaning and milking, which take place on farms. Although milking can be carried out manually, it is often mechanized by connecting the cow’s udders to automatic milking machines.

The pasteurization process is intended to kill all microorganisms that may be present in milk. In Colombia, it is exclusive to formal channels, in sharp contrast with informal channels, which trade nonpasteurized raw milk.

4.2. Identification and description of links and stages

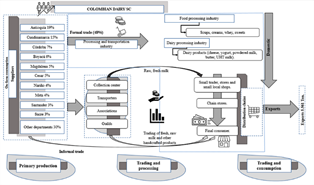

The Colombian dairy product SC is detailed in Figure 2.

Figure 2 shows the three links that make up the Colombian dairy SC. The production link reveals an important weakness related to low investment in the modernization of its systems. In this sense, the highest costs of this link correspond to health, supplies and services. In turn, labor, which is not so expensive, is certainly costlier than milking and feeding. Hence, the situation imposed by this cost structure certainly reduces SC competitiveness.

In 2019, 71% of milk production was concentrated in 10 of the 32 departments of the country, which is greatly favored by water availability and, consequently, good forage potential. Indeed, Colombia has 28 million hectares of suitable land for milk production.

The most important agents in the second link are traders and the processing industry. Although part of the milk is directly sold by producers to final consumers, a good deal of it flows through formal and informal processing channels. The importance of the formal processing channel lies in the fact that it guarantees fair payment to raw milk distributors. From this channel, milk can be sold to the final consumer or to an intermediate trader or processing industry. In the latter case, the raw material is processed under strict hygiene and health standards, resulting in value-added derivatives that are then sold to the public.

For its part, the informal processing channel operates through regional collection centers and specialized depots that deliver the raw material to small or medium-sized processing industries. Most of the products elaborated by the mentioned two processing channels are consumed in the country, while a smaller fraction is exported. In 2019, Colombia exported 5,561 tons of dairy products. Colombia has different destinations for milk (Table 6) FEDEGAN (2021b)

Table 6 Uses of milk production in 2020

| Destination | Million liters | Destination | Million liters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-consumption | 658 | On-farm processing | 769 |

| Industrial Stockpiling | 2,329 | Informal | 2,617 |

| Cooperatives | 1,020 |

Source: milk price monitoring unit (USP), DANE and ENA. Taken from FEDEGAN (2021b).

Farm-processed milk is the result of both dual-purpose livestock production and dairy farming. In informal gathering channels, farmers usually process milk into artisanal products such as cheese and curd, which then take short distribution routes to reach the final consumer. These informal channels, which usually operate at the level of small municipalities, receive most of the national milk production. This shows the importance of raw milk, curd and on-farm consumption.

Regarding the formal channels, industrial milk collection is also very important. It is usually operated by cooperatives that collect and sell the raw material to processing industries in the secondary and tertiary sectors of the economy. However, in certain cases, the milk is directly sold by the primary producers to the processing plants. In any case, the value added by the industrial collection and processing of milk benefits both the farmers and the final consumers. While the latter gain access to a variety of useful derivatives, the price at which they are sold also favors the primary producers. Table 7 shows the national yearly milk collection from 2013 to 2020.

Table 7 Milk collection in Colombia during the first semester of the years 2013 to 2020

| Year | Million liters | Year | Million liters |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 3,129 | 2017 | 3,381 |

| 2014 | 3,291 | 2018 | 3,416 |

| 2015 | 3,286 | 2019 | 3,171 |

| 2016 | 3,218 | 2020 | 3,348 |

Source: FEDEGAN (2021b).

Formal gathering channels have recently undergone intense variations. National milk collection went from 1,726 million l during the first semester of 2018 to 1,523 million l during the same period of 2019, which represents a 13.33% drop. In contrast, there was a 7.07% increase in 2020, when production reached 1,637 million l.

As is the case with any other product, Colombian milk prices are determined by both offer and demand. Whereas the former is mainly a function of climate variability, the latter tends to be lowered by the weak purchasing power of the majority of the population, especially the less favored socioeconomic strata. Thus, this SC is in urgent need of better prices, which, in turn, depend on modernized production and commercialization systems (FEDEGAN, 2021b).

Table 8 shows the yearly growth of the Colombian dairy sector from 2010 to 2015. These data reveal a remarkable production drop determined by the El Niño phenomenon, which started at the end of 2018. In spite of that, production during this year increased by 2.3%, while milk collection scarcely underwent a 1% rise. Regarding 2019, the full activity of El Niño can be observed in the meager 3,170 million liters of milk that were collected in this year, which is the lowest record since 2013. These results clearly show that 2019 was not a good year for the dairy sector. Formal collection dropped after 2 years of growth, whereas powdered milk and dairy derivative imports were the highest ever (Agronet, 2020).

Table 8 Milk production and collection (million liters)

| Year | Production | Year | Production |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 6,617 | 2017 | 7,094 |

| 2014 | 6,717 | 2018 | 7,257 |

| 2015 | 6,623 | 2019 | 7,184 |

| 2016 | 6,391 | 2020 | 7,393 |

Source: USP - calculations (FEDEGAN, 2021b).

4.3. Description of agents and links of the dairy SC

4.3.1.1. First link: Primary producers.

The importance of primary production in the dairy sector became clear in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic. In effect, despite the difficult conditions imposed by the situation, cash flow in this particular sector remained unaffected, as did the important fraction (20%) of all agricultural jobs that it generates.

The first link of the chain is mainly composed of livestock and suppliers. The different livestock types available in Colombia correspond to meat cattle, which are concentrated in the eastern plains; dairy cattle, located in the Andean zone; and dual-purpose breeds, grown in the Caribbean zone. In turn, cattle raising suppliers include those providing supplements, vaccines, improved pastures, fodder, seeds, laxatives and water, among others (FEDEGAN, 2009a).

Grazing contemplates several considerations:

Soil amendments according to acidity.

Determining the appropriate number of heads per hectare, which depends on forage requirements, which are, in turn, determined by the season.

Pasture selection. Determining the type of forage on which cattle are going to be raised requires both a bromatological analysis and a soil study. This is the input of the decision-making process, which usually selects between two or three species of improved pastures, taking into account nutritional quality, soil and climate suitability, growth speed, resistance to pests and animal palatability.

In 2018, Colombia had a diverse cattle herd (Table 9). The largest fraction corresponded to breeding livestock, with 9.16 million heads, followed by dual-purpose (8.22 million heads), fattening (4.7 million heads) and dairy (1.41 million heads) cattle (MinAgricultura, 2020a). An estimation of milk productivity prepared by the Agricultural Rural Planning Unit (Unidad de Planificación Rural Agropecuaria [UPRA]), the MinAgricultura and the Dane in 2017 indicates that dairy cattle are more abundant and cover larger areas in the high tropics, which is the case for the departments of Nariño, southeastern Antioquia and the Cundinamarca-Boyaca high plains (Table 9). This situation favors formal commercialization since the tertiary and secondary roads of some of these departments are among the best ones in the country.

Table 9 Estimation of milk productivity indicators in 2017

| Altitude | Orientation | Productivity per cow | Productivity by area | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L/(cow*year) | L/(cow* day) | L/(ha* year) | kg Useful solids/(ha * year) | ||

| High Tropic | Milk | 3,689 | 10.11 | 3.481 | 262 |

| Dual purpose | 2,542 | 6.96 | 771 | 55 | |

| Low Tropics | Milk | 2,153 | 5.9 | 1.134 | 83 |

| Dual purpose | 1,967 | 5.39 | 757 | 56 | |

| Meat | 1,499 | 4.11 | 133 | 10 | |

| National indicator | 2,156 | 5.91 | 505 | 36 | |

Source: Adapted from MinAgricultura (2020a).

Although the Colombian dairy supply chain has made considerable progress in terms of milk compositional quality, it still lags behind benchmark countries, especially in terms of hygiene standards. This situation results from the remarkable disintegration of the chain at this stage regarding aspects such as regulatory control, compliance, culture of illegality and lack of consumer education (MinAgricultura, 2020a). As a consequence, low investment levels in education and modernization can be observed in this link.

4.3.2.1. Traders and Processing.

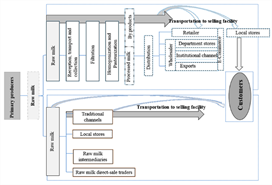

The collection and distribution processes mainly depend on marketing and both formal and informal processing channels (Figure 3).

Informal: The primary producer sells raw milk to the final consumers, either directly or through an intermediary, without applying any value-adding treatment, which also complicates sanitary control.

Formal: Production and marketing begin by registering the cattle herd with the Colombian Agricultural Institute (Instituto Colombiano Agropecuario - [ICA]). The trading process requires compliance with health regulation standards and the daily registration of milk production per cow with established companies engaged in collection, distribution and/or processing.

Dairy collection centers are facilities intended for the reception, storage, refrigeration and transfer of raw milk to the processing plants, the final consumer and/or other destinations (Government of Cundinamarca and Secretariat of Science, Technology and Innovation (Gobierno de Cundinamarca y Secretaría de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación, 2018).

The main function of collectors is to facilitate trade to livestock farmers, especially those with low technology adoption levels. This, in turn, depends on the formal milk processing capacity of the region, among other factors such as milk origin traceability and safe transportation and preservation in adequate refrigeration systems.

Collectors go from farm to farm, gathering the milk and transporting it to a processing plant, for which they obtain a commission. In this regard, an important factor is the distance they have to cover, which is inversely related to the value of the milk paid to the primary producer. This activity depends, to a large extent, on the formality of the channel. Informal collection is a widespread modality throughout most of the country. However, it pays lower prices per liter and does not respect USP guidelines established by the MinAgricultura.

On October 8, 2020, the president of FEDEGAN (José Félix Lafaurie) requested the vice president of the nation and the MinAgricultura to relaunch the Pact for the Growth and Economic Revival of the Dairy Sector. This is an important measure due to its social impact, since more than 330,000 families work in this sector, which accounts for 0.6% of the national GDP.

The transportation of raw milk to the processing plant is the first distribution process. The second process takes place through direct selling from the processor or producer to local stores or chain stores (Figure 3).

4.3.3. Industrial producers.

Colombian milk production depends on the season of the year, which can be dry or rainy. In turn, climate conditions are affected by the La Niña and El Niño phenomena, which was the case in 2019, when the country underwent a milk production shortage due to rain scarcity. This, in turn, raised the price of milk and brought about an increase in dairy product imports (FEDEGAN, 2019).

4.3.4. Milk Processing.

The formalization of the Colombian dairy SC is carried out through a series of legal instruments that regulate important aspects such as health and safety. These, in turn, determine the access of the products to international markets. In this regard, formal dairy marketing channels require quality and value-adding processes that are capable of improving aspects such as safety, hygiene, disease control, human resource training and public health risk control.

The scale economy factor also plays an important role in dairy derivative production. The case of heat-based milk powdering plants provides a good example. This particular industry has been considerably affected since it competes with products imported from countries that have much larger scale economies.

Industrial processing is mainly operated by the private sector, which is mostly owned by foreign capital. Approximately 65% of the milk collected through formal channels goes to 5 large companies: Alpina, Alquería, Colanta, Meals de Colombia, and Parmalat (FEDEGAN, 2009b). According to Asoleche, formal collection reached 3,171 million liters in 2019, which accounted for 48% of total milk collection. In 2018, the same figure was 31%, corresponding to 2,117 million liters. Based on these data, it can be said that formal collection raised sectorial employment to 736,000 jobs distributed across 400,000 farms.

4.3.5. Associations and Guilds.

In 1999, Colombia created the National Dairy Council (Consejo Nacional Lácteo [CNL]), which convenes the participation of five dairy sector associations and three ministries to advise the government on all matters related to sector policy. The National Association of Milk Producers (Asociación de Productores de Leche [ANALAC]) and the FEDEGAN represent the milk producers. The Colombian Federation of Milk Producer Cooperatives (Federación Colombiana de Cooperativas de Productores de Leche [FEDECOOLECHE]) represents dairy cooperatives. Colombian Association of Milk Processors (Asociación Colombiana de Procesadores de la Leche [ASOLECHE]) and Colombian Business Association (Asociación de Empresarios de Colombia [ANDI]) represent the dairy industry, and the government is represented by the MinAgricultura, the Ministry of Commerce Industry and Tourism (Ministerio de Comercio, Industria y Turismo [MINCIT]), and the Ministry of Health and Social Protection (Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social [MINSALUD]).

4.3.6.1. Current problems of the sector.

The sector has a series of problems that prevent the strengthening of the SC. Some of the most relevant ones are listed in Table 10, together with their likely solutions.

Table 10 Problems and possible solutions of the dairy sector

| Problems | Possible solutions | Problems | Possible solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Disarticulation of SC links | Strengthening the guild. | Violation of phytosanitary and safety standards | Accompaniment of informal producers by regulatory entities to provide information and technical advice. |

| Government participation and monitoring. | |||

| Promotion and development of an organic milk brand | |||

| Informal sale and consumption of raw milk | Creating campaigns that encourage the formalization of primary producers. | Elevated production and operation costs | Providing government warranties to support production costs and supplies reduction. Large capital injections to build collection centers in formal dairy companies or cooperatives. |

| Formalization of more dairy cooperatives. | |||

| Formal purchase of raw milk from the primary producer, at the price established in the national regulation. | |||

| Transportation | Road infrastructure improvement of and low freight costs. | Cattle rustling and extortion of livestock farmers. | Rural security support. |

| Implementation of a warranted cold chain for the conservation of products and byproducts. | |||

| Improper land use | Good livestock practices. | Technological gap in the sector when compared to foreign competitors | Investment in machine technology, cattle genetic material, pastures and feed. |

| Implementation of silvopastoral models. |

Source: Authors’ own elaboration.

In the face of competition with other producing countries with larger market shares, the Colombian agricultural sector faces great challenges in different aspects, which certainly poses a continuous improvement challenge. However, the country counts with favorable aspects such as its privileged geographical location, natural wealth and biological diversity. This implies good availability of water resources - an advantage that is essential for the improvement of pastures and animal feed - and solar energy throughout the year, as well as direct access to two coasts (Pacific and Caribbean).

The Colombian agricultural sector faces great challenges since it has to compete with countries that enjoy larger market shares. Nonetheless, the country largely benefits from its privileged geographical location, natural wealth and biological diversity. This provides ample advantages in terms of water and solar radiation availability, both of which are very important in regard to the improvement of pastures and animal feed. Finally, Colombia has ample and direct access to the Pacific and Caribbean coasts.

4.4. Diagnosis and conclusions of the SC characterization

To carry out a complete strategic planning exercise, a SWOT analysis was conducted (Table 11). Developed by Stanford University in 1960, this particular type of assessment seeks to facilitate decision-making on the part of agents and stakeholders.

Table 11 SWOT analysis of the Colombian dairy supply chain

| Threats | Opportunities |

|---|---|

| Greater imports of dairy products and derivatives. Sanitary restrictions regarding product quality and innocuousness. Low national growth. Significant technological gap between Colombia and developed countries. Sector specific insecurity problems (extortion to farmers). | Increasing the production of dairy derivatives such as cheese, powdered milk and others. Commercializing dairy products with added value. Availability of hydric resources and soils with good aptness for milk production. Innovation in industrial, artisanal, functional, and organic products with designation of origin. Opportunities to integrate dairy products into nutritional care programs to create consumption habits. |

| Strengths | Weaknesses |

| Difficulty to enter the dairy SC industrial business (that is, the business has towards oligopoly, as the scope of the market increases). Milk and its derivatives have no direct substitutes. Standardized regulation of the chain. Consolidated and largely representative guilds in terms of production and/or processing volume. Highly experienced human resource in all links of the productive chain. Existence of the CNL for the discussion of sector policy and development. Availability of natural resources and suitable agroecological regions for milk production. The formal industry has good training level and applies personnel selection mechanisms. Animals are raised in natural environments with minimum intervention of chemical, biological or genetic agents, mobility restrictions or hindrances to organic milk breeding and production. | Disarticulation between links of the chain due to technological gap, topography, cold chain issues, varying on-farm milk purchase conditions, illegal animal offer, and cooperative and guild disintegration. Easy access of new competitors into the primary, trading and processing sectors. Elevated cost of supplies. Low growth of local and export markets. The guilds are not representative of milk producers or processors. Problems related to training and educational level in the primary sector that generate resistance to change and maintain informal traders and scarcely efficient traditional production systems. These conditions, in turn, negatively affect production costs in rural areas. Low compliance with the mechanisms proposed for the stabilization of the dairy sector in agreements 17 and 18 of the Ministry of Agriculture and other regulations. Low access of farmers to modern refrigeration, irrigation and milking technologies. Restricted access to irrigation districts, housing and public utilities. |

Source: Authors’ own elaboration.

5. Conclusions

The logistic operations involved in the dairy supply chain, which constitute the basis for its decision-making processes, are here characterized in detail. On these grounds, the present analysis constitutes a technical contribution to the literature on SC management.

The characterization methodology employed in this work carefully assesses the value added by each link of the studied supply chain.

The current study revealed weakness in the upstream phase, which is the most vulnerable part of the chain, since it absorbs most of the risk and has the lowest financial leverage. As a consequence, it usually faces profitability problems. This is actually a common trend in the literature on the topic, as seen in previous agribusiness SC analyses, wherein similar weaknesses have been revealed.

The study shows that a considerable part of the agents of the chain are currently facing disarticulation problems. It is worth mentioning, however, that some milk suppliers, who provide raw materials to large processing companies, have implemented remarkable cluster-type organization modes.

Although this industry is becoming increasingly demanding in terms of quality standards, national production and logistic processes clearly lag behind more advanced international actors. This is particularly true about small farmers and processors, who tend to apply artisanal procedures that make it difficult to conform to international quality norms and become efficient enough to obtain adequate profits.

Despite the aforementioned weaknesses, this is a mature SC with important companies. Among them, we can count large national organizations such as Alpina and Colanta, mixed capital organizations such as Danone-Alquería, and foreign capital ones, as is the case of Meals and Parmalat. These organizations have supported not only small farmers and their herds but also the development of small and medium-sized processing companies that operate at the regional level, such as Peslac and Proleca.

Research prospects include the development of tactical and operational characterizations of the SC, as well as new developments that allow synergic integration with related SCs to facilitate and promote their development.

Lessons learned from the application of the current methodology indicate that it should continue to be developed to absorb all the strategic decisions and problems identified in the literature.