1. Introduction

In 1890, the first School Meal Program (SMP or PAE in Spanish) was created by Ellen H. Richards who analyzed how malnourished students had difficulty focusing. H. designed a program in Boston, United States; to provide lunch to more than 2000 students and among her results she reported an “increase in weight, better color, and more receptive and active minds” (Swallow, 2014). They designed a table with costs and nutritional value of each of the food items to facilitate the implementation of their program.

The aim of the PAE is to provide nutritional support to public education students, especially children and adolescents. These programs offer a range of dietary, nutritional, and health services, along with training on appropriate eating habits and healthy lifestyle choices. The intention behind these initiatives is to enhance the academic achievements of students while promoting their retention and enrollment in the education system (Ministerio de Educación Nacional de Colombia, 2010).

Levinger (1986), a pioneer of School Meal Programs (SMPs), identified three objectives that these programs typically pursue: increased student enrollment and attendance, improved nutritional status, and academic performance.

Multiple researchers have also emphasized the importance of school meals in education and their potential to provide children with an ideal opportunity to learn, understand, and implement healthy eating habits (Pérez-Rodrigo and Aranceta, 2001; Aranceta Bartrina et al., 2004).

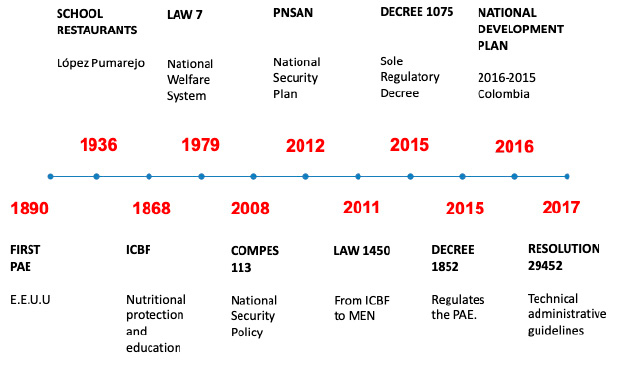

According to the Ministerio de Educación Nacional de Colombia (Ministry of National Education’s publication) [MEN], the first School Meals Program (SMP) in Colombia was instituted by the government of López Pumarejo in 1936 via Decree 219, granting permanent funds to school restaurants. In 1968, the Instituto Colombiano de Bienestar Familiar (Colombian Institute of Family Welfare) [ICBF] was established and assumed the administration of the Nutritional Protection and Food Education Project for official schools, the former designation of the SMP.

In 2011, Law 1450 transferred PAE responsibilities from ICBF to the MEN to expand the program’s funding sources and achieve universal coverage. MEN now reviews, updates, and defines technical-administrative guidelines, standards, and conditions for service provision in implementing the program.

The MEN defines and regulates the PAE as a state strategy that promotes the school permanence of children, adolescents and young people in the official education system by delivering a food supplement and seeks to improve learning processes and promote healthy lifestyles.

Likewise, in 2019 and under the national development plan 2018-2022 “Pact for Colombia, Pact for Equity”, the special administrative unit for school meals was created, whose purpose is, among others, to strengthen the financing schemes of the School Meals Program, expand its coverage and ensure the continuity of the program.

Currently, the PAE in Colombia involves multiple actors: MEN, Governors, Secretariats, Operators, Organizations, Parents, just to name a few and, additionally, it is the program with the greatest “concurrence” of resources and with greater opportunities for co-management among actors as indicated in the Technical-Administrative Guidelines and Standards of the School Meals Program (MEN, 2010).

The technical guidelines emphasize social control as a mechanism for participation, to provide strategies and support spaces enabling networks of observers to control public resources.

The PAE in Colombia has undergone an evolution in resource management by shifting from centralized administration to decentralized administration among national, state, and local institutions. The program has implemented information systems to oversee its operations, enforced social control, and engaged private entities in service delivery.

Research on PAE has been conducted in social and medical sciences in academia, with some studies also exploring the subject in agricultural and engineering sciences. This demonstrates the multidisciplinary nature of the topic. In the last 5 years, literature has suggested a shift towards the prevention of diseases associated with the environment, nutrition, education and health, including pediatrics and internal medicine. At the local level, the majority of graduate work related to health at Universidad del Valle has focused on various areas, ranging from sports sciences and occupational therapy to public health.

Since their emergence in 1910, researchers who have analyzed SMPs have honed in on schools as privileged locations for promoting healthy lifestyles and preventing chronic non-communicable diseases such as obesity and diabetes.

Along these lines, Soares de Almeida points out the potential of school meal programs to establish healthy eating habits because these are carried out in an environment in which children, educators, parents, cooks and institutions are present and highlight the need to incorporate additional items beyond food rations. Research related to public policies highlights the potential of school meal programs in the formation of healthy eating habits and the importance of school meals in the education process. (Pérez-Rodrigo and Aranceta, 2001; Figueroa and Martinez, 2017) and Jesús Martínez in his book “Nutrition and food in the school environment” highlights the role of the “school canteen” in the health and training of the individual highlighting that it can provide quality food adapted to the needs of users and be a didactic and complementary resource for the school in health education, both in terms of food and hygiene and other aspects (Martínez Álvarez, 2012).

Moreover, multiple studies highlight the need to integrate the different nutrition education programs and identify the pending challenges. This is the conclusion of researchers (Cervato-Mancuso et al., 2013), who conducted a study with nutritionists affiliated with the SMP in Chile to evaluate the school menu design and its educational element. Among their findings, it is worth noting that the implementation of educational strategies on food and nutrition is a priority for students and one of the ways to achieve this is to view the program as an instrument for nutrition education (Cervato-Mancuso et al., 2013).

Similarly, (Alderman and Bundy, 2012) questioned the efficiency and design of SMPs. In their work, these authors analyze the different approaches to SMPs; when employed as a nutrition program, when viewed as an education program and when considered as “safety net” programs, and point out that it is not possible to ensure that SMPs can be categorized as the best investment for nutrition and further conclude that the priority for sustaining these programs lies in costs, their sustainability and understanding where the best place to deploy them is (Alderman and Bundy, 2012).

At the national level, various institutions have been concerned with assessing the level of efficiency achieved with the SMP in the country, as was done by the auditors’ office using a problem tree methodology in 2016. In 2016, territorial entities did not articulate the sources of resources, which led to 32.7 million rations not being delivered in that year. Therefore, it highlighted that the SMP is a program with three main variables, focused on coverage: days of attention, rations supplied and children served (Contraloría General de la República de Colombia, 2017).

Other studies have focused quantitatively (Vergara Varela and Rodríguez Vásquez, 2016) on understanding: how many children were served? What is the enrollment rate? While, at the local level, a diagnosis of the SMP of the [MEN] in the city of Cali, studied the promotion of healthy habits and lifestyles from the program; concluding that a high percentage of students do not know what healthy habits and lifestyles are (Villamil Meza and Ballesteros García, 2018)

Similarly, some research has determined that it is not only important to implement educational strategies in food and nutrition for students but also requires regulatory actions and educational planning in this regard (Cervato-Mancuso et al., 2013).

Despite multiple studies highlighting the potential of the PAE to promote healthy eating habits and pointing out the need to analyze other dimensions, the reports produced in Colombia on its operation focus on evaluating its efficiency, but do not explore how the program contributes to the formation of healthy eating habits in the beneficiaries. An example are the reports presented by the Audit Office (2016) and the First Follow-up Report on the Plan Nacional de Seguridad Alimentaria y Nutricional (the nacional Food and Nutrition Security Plan) 2012-2019, conducted by (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations) [FAO] (2016) where it is mentioned as an aspect to improve training on issues related to nutritional food security, healthy lifestyles and compliance with Law 1355 of 2009.

This is a serious public issue, as malnutrition affects one out of every three people in the world and, according to the Pan American Health Organization, the developmental, economic, social and medical consequences are severe and long-lasting. Likewise, it is estimated that non-communicable diseases (NCDs) kill 41 million people each year. This is 71% of the deaths that occur in the world (2020).

Colombia is no stranger to this and according to data from the ENSIN 2015 46% of adults, 24% of schoolchildren aged 5 to 12 years and 17% of adolescents aged 13 to 18 years are overweight.

This means that, even though there have been efforts to promote healthy eating habits and that obesity has been declared a chronic public health condition through Law 1355 of 2009, nutrition continues to be a challenge in the country.

Likewise, the burden is high: the former Minister of Health and Social ProtectionAlejandro Gaviria reported at the public hearing on ‘Eating habits in Colombia and their impact on health’ that NCDs associated with obesity and overweight generate an annual expenditure to the system of 1.2 trillion (Consultor Salud, 2015)

The PAE can have a positive and lasting impact on children and the community, so evaluations should analyze the efficiency of the use of available resources and assess whether they achieve the stated objectives and generate positive changes in the habits of the beneficiaries. It is necessary to evaluate additional factors besides efficiency in the use of resources to ensure that the EAPs meet their objectives and help their beneficiaries effectively.

The National Guidelines for Food and Nutrition Education stipulates that the PAE should ensure learning processes that promote healthy eating, integrating theory with practice, introducing new foods, reinforcing healthy eating habits, prevention of hunger and malnutrition and based on the definition of public policy proposed by Oszlak and O’Donnell, 1995, the following question emerges: How has the pillar of promoting healthy eating habits of the school program been implemented in Cali?

To provide an answer to the of above, the article focuses on evaluating the implementation of the PAE (or SMP) with special emphasis on its component of formation of healthy eating habits during 2016-2019 in a public school in Santiago de Cali, and its objectives are to describe the national and local guidelines for the PAE (or SMP) in Cali and characterize the implementation processes of the PAE (or SMP) in Cali based on its Program’s theory.

1.1. Public management models

Modern states have undergone numerous transformations in attempts to modify the management of the state apparatus. At the end of the 19th century, one such transformation was implemented with the adoption of the Weberian bureaucratic model. This reform established a professional and merit-based public service, as stated by the Latin American Center of Administration for Development [CLAD] (1999).

The Weberian model was the primary managerial model for almost a century; nevertheless, it encountered challenges in meeting the post-World War II demands. It was a strict, procedure-oriented model with numerous regulations and standards that made it arduous to fulfill the needs of state modernization:

“In short, efficiency, democratization of public service and organizational flexibilization, are basic ingredients for the modernization of the public sector that the organizational paradigm of bureaucratic public administration does not contemplate” (Consejo Científico CLAD, 1999).

With the conclusion of the Cold War, a specific set of circumstances (Kettl, 2000) emerged that necessitated the exploration of innovative approaches to governing at the national level:

Nations, such as those of the former Soviet Union, had to reconsider their relationship with citizens and devise institutions more attuned to their needs.

In multiple industrialized countries, living standards remained static, necessitating a two-person income to provide what one person previously could. The welfare state faces a crisis.

The shift from the industrial age to the information age is underway.

NGOs and supranational structures should play a more significant role in public discourse.

The recent economic crisis, which resulted in a shortage of jobs, has led to reduced regulation and increased public pressure to privatize entities for economic growth.

In this setting, what has been termed as “first and second generation reforms” or “outward” and “inward” reforms by Oszlak (1999) arose. These reforms aimed to reduce the size of the state apparatus and enhance its management. Several aspects of these changes are outlined below.

1.1.1. First-generation reforms or “outward” reforms.

According to Oszlak, there are two common types of situations found in these reforms. Either the state ceases its involvement in producing goods, providing services, or having an impact in a specific field, or some public employees are completely removed without anyone to replace them. Examples of the first scenario where the State reduces its responsibility include the privatization of public companies, outsourcing some services (thereby involving the market), or discontinuing subsidies for certain services.

Staff reductions through voluntary retirements, early retirements, or agreements are often employed during reforms, which involve changes in legal relations and agreements among actors in the transfer of public policies. Such reductions have significant economic consequences.

1.1.2. Second-generation or “inward” reforms.

Unlike the first-generation reforms that primarily focused on fiscal issues (downsizing), these reforms prioritize cultural and technological changes to the State (Oszlak, 1999). “The managerial reform of the Latin American State” is how CLAD categorizes these changes, considering it the most effective solution to Latin America’s economic, social, and political challenges.

According to CLAD, the reforms respond to the changing role of the state in economic and social sectors. The state must focus on the establishment of tools for promoting economic development and primarily on the social area. This includes assuming the role of regulator, formulator, and financier of public policies.

The overarching goal of the Managerial Reform is to ensure greater efficiency, flexibility, and accountability, and several methods are proposed to achieve this.

Bresser-Pereira and Cunill Grau (1998) of the Getulio Vargas Foundation notes a trend in the largest countries of the region to transfer powers, resources, and accountability from the central level to subnational units of government. This strategy seeks to achieve greater decentralization or devolution and autonomy within the same system, while reducing bureaucratic controls. Additionally, it aims to increase citizen oversight and improve efficiency.

Unlike the Weberian model, which emphasizes processes, the new public management puts emphasis on results. This does not imply that the former model did not focus on impacts. However, the primary premise guiding the latter is limited trust rather than total distrust in public officials (Consejo Científico CLAD, 1999). However, the primary premise guiding the latter is limited trust rather than total distrust in public officials (Consejo Científico CLAD, 1999). However, the primary premise guiding the latter is limited trust rather than total distrust in public officials (Consejo Científico CLAD, 1999). The implementation of information systems and the generation of updated and decentralized data have emerged as outcomes of the information era, leading to the definition of performance indicators at multiple levels.

Accountability: Decentralization enhances “political participation or the use of social control or social accountability mechanisms” (Bresser-Pereira and Cunill Grau, 1998), making it easier for various stakeholders to monitor the State’s activities at the local level.

In essence, three forms of control are present: social control, business contract and result-based control, and controlled competition. All three controls aim to hold officials and organizations accountable for their actions.

The non-state public space in which the State recognizes the capacity of society to act alongside it in the provision of public services (Consejo Científico CLAD, 1999) positions itself as a financier and regulator. To make public administration more flexible, efficient, cooperative, and democratic with the third sector and the market.

Orientation of the service towards the citizen-user: as opposed to asserting the State’s power, the provision of public services is now directed towards citizens, who are viewed as users and thus prioritized in meeting their needs and demands. Quality is emphasized, and citizens are encouraged to play a larger role in evaluating and managing public policies.

1.2. Evaluation in the new public management

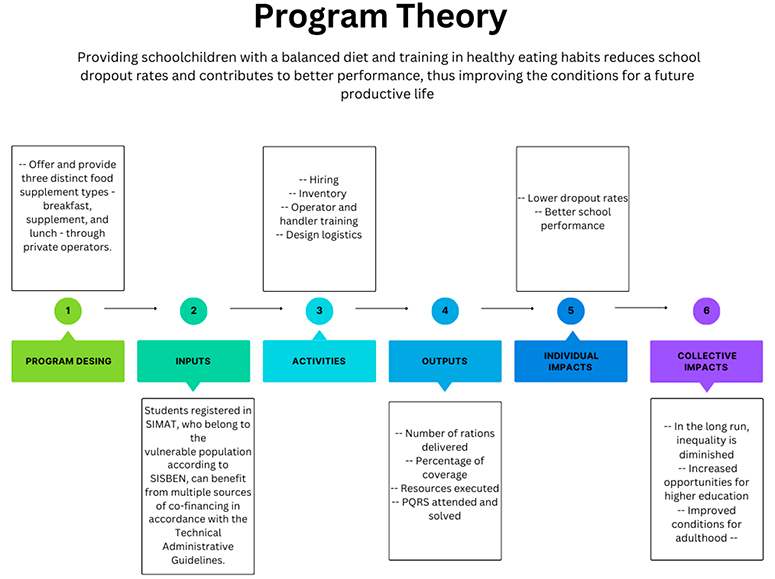

A program inherently holds a theory of social change (Solarte, 2004). In the context of liberal states such as Colombia, the supporting social intervention is designed and executed rationally (Weiss, 1992). The program theory presents the hypothesis, providing basic assumptions that initiate the intervention, and cause-and-effect relationships explaining how inputs will be operationalized into products or results (Solarte, 2004).

Additionally, the program theory contextualizes the social intervention and ensures coherence with public problems. The implementation theory outlines the process of translating program objectives into practical actions and operations through various stages including inputs/resources, actions, outputs, products, effects, and the welfare impact resulting from those actions. Objective evaluations have been excluded unless explicitly marked as such, and academic conventions such as clear structure with logical progression, precise word choice with consistent technical terms, and grammatical correctness have been followed. Additionally, formal register has been maintained, and clear, objective, and value-neutral language has been used with no biased, emotional or ornamental language. Finally, consistent citation, footnote style, and formatting features have been adhered to.

2. Methodology

This research, of an explanatory nature, used interviews with actors in the process and documentary analysis of data and institutional documents. In Addition, semi-structured interviews were conducted with 1 public official and 1 director of an educational institution in the public sector. The main criteria for the selection of participants was to select people who were publicly involved in the implementation and management of the PAE in Cali and who had experience and knowledge in the implementation and management of the program. This data collection strategy was accompanied by the signing of individual informed consents by the participants and the information will be kept in the author’s files.

The analysis method of analysis used was the thematic network strategy, which allows the analysis of qualitative data (Attride-Stirling, 2016) through the exploration and understanding of a topic by organizing the concepts that emerge from a text at different levels as a “spider web”, which is an organizing principle that facilitates its interpretation through graphs.

The process of analyzing qualitative data through thematic networks begins with the selection of the text to be analyzed, which in this case were the documents of Villamil Meza and Ballesteros (2018), the final Report of the Comptroller’s Office: Performance Audit of the PAE (2017), Report of the supervision contract service provision contract No. 4143.0.10.26.1.015, March 1 to 31, 2019 (Alcaldía de Santiago de Cali, 2019) and the Administrative Technical Guidelines And Standards of the School Feeding Program (MEN, 2010). Once the text is selected, it is transcribed and a document is created with the words and phrases of the original text, in order to identify the key concepts arising from the text.

The concepts are then organized at different levels and, when the thematic network is created, the results are interpreted. That is, to analyze how the different concepts are related to each other and how they contribute to the understanding of the topic of study.

In the case of this research, Taguette tool was used to make concepts visible in each of the documents and then they were grouped into three large groups: factors that can strengthen the PAE, factors that can weaken the PAE, program definition and effects versus results.

3. Results

In Colombia, the first SMP was regulated by the government of López Pumarejo through Decree 219 and in 1968 the ICBF was created, which assumed the execution of the Nutritional Protection and Food Education Project in official schools, the name under which the PAE operated.

In 2011, through Law 1450, the functions were transferred from the ICBF to the MEN in order to diversify funding sources in order to achieve universal coverage.

Likewise, in 2019 and under the national development plan 2018-2022 “Pact For Colombia, Pact For Equity” it is proposed to create the special administrative unit of school feeding that aims, among others, to strengthen the financing schemes of the SMP, define schemes to promote transparency in the contracting of the SMP, expand its coverage and ensure continuity with technical criteria of targeting and ensure the quality and safety of school feeding.

Since its design, the PAE has linked the lack of adequate food with high dropout rates, this being its guiding principle. The PAE is based on the theory that by offering a nutritional supplement, students and their parents will remain in the educational circuit. This would result in better performance of children and adolescents, their permanence in the institution and a more productive future.

The program uses an information system focused on the population with nutritional and socioeconomic vulnerability that evaluates food supplements delivered versus the number of prioritized students. This database is known as Sistema de Información de Matrícula (Enrollment Information System) [SIMAT].

On the output level, the main elements are the number of rations delivered, the percentage of coverage, the budget execution, the number of PQRS attended and solved.

Likewise, it is observed that since the 1991 Constitution, several public policies in Colombia have adapted elements of the New Public Management in their design and implementation, the School Feeding Program being an example of this. Principles such as decentralization, focus on results and accountability processes are present throughout the entire PAE chain.

From decentralization we see how the program was implemented entirely by the central government under the tutelage of the Colombian Institute of Family Welfare and the Ministry of National Education to be coordinated with regional and local levels since 2001 with Law 715.

Another of the guiding principles of the New Public Management is the focus on results and the promotion of information systems that make it possible to follow up on plans, programs and projects. This has been observed since the entry into force of the PAE Technical Guidelines, which established a system for tracking and monitoring resources allocated to school meals and all its funding sources. ICBF is in charge of its follow-up and control and seeks to monitor the coverage achieved and the efficiency in the use of the program’s resources.

Similarly, the Manual of Responsibilities and Competencies of the Actors Participating in the School Feeding Program includes two essential components of accountability: social control and control through management contracts and results. The concept of “social management” within the framework encompasses both control and social participation. In the context of the PAE, social management is defined as a mechanism that promotes social cohesion and effective social integration of the community in social projects, while social control is described as a modality of citizen participation or a form of “social self-regulation”, as defined by the (Universidad Nacional de Colombia, 2013).

Similarly, some traits of the NGP related to the provision of public services by actors external to the State are also identified. This is known in some texts as the non-state public space (Consejo Científico CLAD, 1999).

The PAE, although designed and supervised by the State, is executed by external operators. These operators compete in a free market scenario through public procurement, thus providing a public service.

The fact that the PAE is implemented by private operators should not be interpreted as a privatization of the school feeding service, since the State continues to play a very strong role in its role as financier and regulator. Proof of this can be found in the guidelines, which state that, although the operators implement the program, the Municipal Social Policy Councils articulate and design the policy. Figure 1 presents a chronological overview of PAE legislation in Colombia, illustrating the evolution of such legislation over time.

At the local level, the city of Santiago de Cali in its 2016-2019 development plan, through agreement 0936 of 2016, stipulates that “equitable and inclusive public education” will be promoted through actions aimed at improving educational coverage, including the PAE reaching 100% coverage of the city’s educational institutions.

In the same way, this research conducted interviews and analyzed interviews with the principal of the Francisco José Lloreda Mera Educational Institution, the coordinator of the PAE during the administration of the Mayor of Cali Norman Maurice Armitage in the period 2016-2019, the supervision report of the contract Fundación Prodesarrollo Comunitario Acción Por Colombia and the Technical Administrative Guidelines and Standards of the School Feeding Program finding common categories and concepts. Subsequently, the Taguette tool was used to make these concepts visible in each of the documents and group them into: factors that can strengthen the PAE, factors that can weaken the PAE, program definition and effects versus results, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1 SMP (PAE) categories and concepts

| Factors that can strengthen the PAE | Factors that may weaken the PAE | Program definition |

|---|---|---|

| Bidding processes | Inadequate performance indicators | School dropouts |

| Performance indicators | Lack of interest from stakeholders | Control mechanisms |

| Reporting systems | Insufficient or ineffective controls | Healthy eating |

| Decentralization | Monopolies | Defined roles |

| Citizen oversight | Lack of political will | Financial control |

| Political will | Complicated standards to comply with | Procurement |

Source: Authors’ own elaboration.

4. Discussion

The NPM has had a strong influence on the program, especially in its decentralization components, focus on results and accountability processes. As a result, elements such as co-responsibility, bidding processes, information systems, community participation and the entry of private operators for the provision of a public service have been incorporated.

This has achieved important advances, especially a greater coverage of children. According to the analysis of the program’s theory, the PAE seeks to reduce school dropout rates and contribute to better school performance of children. This is based on the delivery of nutritional supplements and the formation of nutritional habits. The following Figure 2 illustrates the theoretical model. It is important to consider both individual and collective impacts in any type of evaluation.

But, although it is identified through documents and interviews, that the main object of the PAE related to the delivery of food supplements is fulfilled to a greater extent, there is a gap regarding the formation of healthy habits when the program is implemented. “Promote the implementation of cross-cutting pedagogical projects on healthy lifestyles.”

This objective, although important, is measured only superficially in the supervision reports and is limited to verifying that the operator has done some related activity.

Moreover, during the investigation, no mention was found of the school dropout rate in the control and follow-up reports, in the public roundtables, in the contracting specifications or in the operators’ reports. This is of concern because it is important to evaluate whether the PAE is really achieving its main objective. In addition, it is important to know these dropout rates in order to identify areas where more intervention is needed and to be able to measure the success of the PAE, or even if it has any bearing on the reduction of these rates. Without adequate monitoring and evaluation, it is difficult to determine whether the program is being effective in achieving its primary objective of reducing dropout rates.

In 1992, authors Osborne and Gaebler pointed out how the U.S. bureaucracy planned all its programs from outcomes rather than effects. In their analysis, these two authors argued that this measurement approach generally resulted in policies that did not achieve much and in decision-makers who did not know how to recognize whether the programs funded by their efforts were successful or not.

The Methodological Guide for the monitoring and evaluation of public policies of the National Planning Department distinguishes between the terms efficiency, efficacy and effectiveness. The first refers to the optimal use of resources for a specific activity, comparing what was produced with what was expected to be produced with a given number of inputs. Effectiveness, on the other hand, refers to the degree of compliance with goals at the level of outputs and results and, finally, effectiveness attempts to answer in what percentage the desired results are achieved through the outputs (Dirección de Seguimiento y Evaluación de Políticas Públicas, 2014).

The PAE seems to be focused on measuring results (or efficiency in terms of the DNP) and not effects, thus repeating old patterns. In the II public roundtable of 2020 of the School Feeding Program, the results measured are recounted; going through coverage, rations delivered, petitions and claims addressed, food preparation methods, number of CAES established and a summary of the results of the contractual processes. There is not a single piece of data related to school performance, school dropout or nutritional status of children and adolescents. The fact that the PAE does not include data related to school performance or dropout in its measurements is contradictory to say the least, especially when it is part of its main objective.

In light of the figures, it cannot be argued that the program has been effective in reducing school dropout rates, since the Cali Cómo Vamos (2022) report showed that school dropout rates in elementary and secondary education increased by about 3%, which could be justified by the effects of the pandemic. However, the same report, but in its pre-pandemic 2019 edition, exposed an increase in this rate (5.3%) compared to the last 3 years (2% in 2015).

Now, if we analyze the nutritional status of Cali residents, we find how the most recent data report that 16.7% of children in transition and primary school in the city are obese. An increase of 3.5 points compared to 2020. And, about 30% of children, adolescents and young people suffer from overweight. These two indexes are closely related to the formation of healthy habits, one of the secondary objectives of the PAE (Cali Cómo Vamos 2022).

With these figures, it is crucial to include indicators and evaluation methods that take into account the school dropout rate and the nutritional status of program beneficiaries in order to fully understand the impact of the program. School dropout and malnutrition are closely related, and can affect children’s academic performance and overall well-being. In addition, by measuring both dropout rate and nutritional status, a more accurate picture of program impact can be obtained and adjustments can be made to improve the program. Without these indicators and evaluation methodologies, the actual impact of the program may be underestimated or overestimated and opportunities to improve the program and make it more effective may be missed.

5.Conclusions

This article provides an initial evaluative perspective on the effectiveness of the PAE program, which transcends the evaluation based on accountability or audits. The PAE is efficient and in accordance with the postulates of the New Public Management, the PAE is successful. Coverage has increased progressively over the years, rations are delivered without major mishaps and complaints regarding food quality are a minority in the city. However, the effectiveness of the PAE is not so, since from the program’s theory, it is designed to reduce school dropout rates, but the absence of indicators of the program and school dropout, as well as between the PAE and the formation of healthy habits are not defined.

In general, the theory of implementation is not successful, which impacts contracting requirements, effective strategies for promoting healthy habits, and the creation of models for informed decision-making on policy transfer to different territories.