1. Introduction

Employees are vital resources for companies, influencing their success or failure. Bakker (2019), Clack (2021), and Turban (2016) posit that employee health, well-being, and engagement are crucial for organizational success. The existing literature extensively highlights the positive impact of employee engagement on organizational success, productivity, and employee well-being. Nevertheless, there is little evidence from the literature for the possible “dark sides” of job engagement. Halbesleben (2011) highlights these dark sides, including the interference of job engagement with family life, the risk of neglecting crucial aspects of roles through job crafting, and the possibility of prioritizing short-term gains over long-term organizational goals. Moreover, Lawler III (2017) underscores the challenges and limitations inherent in the concept of employee engagement.

Burnett and Lisk (2021) discusses the widespread adoption of various engagement surveys by organizations such as Gallup, Kenexa, Aon Hewitt, and Towers Perrin. These surveys assess multiple aspects of employee engagement, including work and organizational commitment. Specifically, the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES) measures work engagement through vigor, dedication, and absorption (Schaufeli et al., 2006). However, despite their popularity, many of these surveys primarily measure employee satisfaction rather than intrinsic motivation or performance outcomes. This focus raises doubts about their effectiveness in driving organizational improvement. Furthermore, the unclear causal relationship between engagement and performance calls into question the actionable insights these surveys provide, thereby making their ability to enhance organizational performance uncertain.

Challenges in sustaining high engagement, as noted by Macey and Schneider (2008), bring attention to potential drawbacks like energy depletion. The argument by Wang et al. (2018) that intense job engagement may lead to negative workplace behaviors and the caution from Cabanas and Illouz (2019) about excessive focus on engagement harming workplace solidarity are noteworthy considerations. Additionally, the link between engagement and overtime (Beckers et al., 2004) raises concerns about work-life balance and health, with engaged employees potentially facing work-family conflicts (Halbesleben et al., 2009) and experiencing burnout and turnover intentions (Moeller et al., 2018). The mixed findings in the relationship between engagement and employee well-being further underscore the need for a comprehensive understanding of the dark sides of engagement.

Emotional labor, often performed by engaged employees, emerges as a crucial aspect with potential adverse outcomes, compromising professionalism, job satisfaction, and contributing to distress and depression symptoms (Pugliesi, 1999). This emphasizes the necessity to examine the potential adverse outcomes associated with emotional labor, impacting the psychological well-being of engaged employees.

This study fills a significant research gap by addressing the dark side of engagement, emphasizing adverse outcomes. More specifically, we examine the positive or negative effects it can have on stress through hiding feelings. Overall, while employee engagement is predominantly studied for its positive outcomes, evidence suggests potential negative consequences, highlighting the importance of a holistic approach in organizational management that considers both the positive and negative aspects of employee engagement. The study, utilizing data from the 2015 European Working Conditions Survey in Greece, contributes fresh insights in a unique Greek setting.

2. Conceptual framework and hypotheses

2.1. Employee engagement

Employee engagement has been defined in various ways. Kahn (1990) initially characterized it as a state where employees utilize their skills, expressing themselves physically, emotionally, and intellectually, leading to positive outcomes individually and organizationally. In contrast, Maslach and Leiter (1997) defined it as a positive, emotionally driven work-related well-being, opposing burnout. The most widely accepted definition, proposed by Schaufeli and Bakker (2003), describes work engagement as an active, positive attitude with three dimensions: Vigor, Dedication, and Absorption. For this study, we embrace the definition of employee engagement proposed by Schaufeli and Bakker (2003) as it aligns with our research objectives and theoretical framework and emphasizes the proactive and positive nature of engagement within the workplace. Furthermore, we choose it due to its widespread acceptance and relevance to contemporary organizational literature. The mainstream of organizational literature suggests that engaged employees exhibit higher energy and enthusiasm, positively impacting performance, organizational well-being, and customer relationships. It also correlates with improved employee health, lower levels of depression, stress, and psychosomatic problems (Demerouti et al., 2001). Furthermore, employee engagement is considered important in fostering employee loyalty and organizational success and is positively related to organizational commitment (Chopra et al., 2023; Sahni, 2021).

2.2. Hiding Feelings

Emotional labor, introduced by Hochschild (1983) and developed by subsequent scholars like Grandey (2000), involves intentional emotion regulation for organizational goals. Scholars explore dimensions like adherence to display rules, the behavioral dimension, and an interactionist approach. Grandey (2000) defines it as regulating emotions for organizational goals, emphasizing its negative impact on employee well-being. We focus on this definition due to its relevance to our research objectives and theoretical framework, as it highlights the detrimental effects of emotional labor on employee well-being and organizational outcomes. It is more common to professions like customer service, where employees hide emotions to meet goals (Pugliesi, 1999). Key elements include emotional rules, surface acting (presenting unfelt emotions), and deep acting (changing felt emotions) (Diefendorff et al., 2005; Sutton and Rafaeli, 1988). The specific focus on hiding feelings, particularly through surface acting, is detrimental, associated with dissatisfaction, burnout, poor job satisfaction, and emotional exhaustion (Hochschild, 1990; Brotheridge and Grandey, 2002; Brotheridge and Lee 2002; Grandey, 2003; Amissah et al., 2021; Chung et al., 2021). Surface acting demands mental resources, impacting cognitive performance, memory, and decision-making. It leads to non-authentic expressions, contributing to emotional exhaustion and depersonalization (Hülsheger and Schewe, 2011). Finally, surface acting has been also found to negatively impact supervisor ratings of in-role performance and Organizational Citizenship Behavior Towards Customers (OCBC) (Lavelle et al., 2021).

2.3. Work Stress

In this study, we adopt the definition of stress as proposed by Selye (1959) where stress refers to a reaction that a person develops when exposed to situations that put them under intense pressure, primarily on an emotional and psychological level. Stress, stemming from efforts to manage uncertainty, elicits unpleasant feelings and physiological reactions (Manos, 1997). It is a response to intense pressure, affecting individuals emotionally and psychologically. Job stress can be defined as the emotional, psychological, and physiological strain experienced by an individual due to perceived adverse conditions or events within the workplace. It encompasses the feelings of discomfort, unwantedness, or threat that an employee may encounter as a result of their work environment (Montgomery et al., 1996; Chen et al., 2006; Guinot et al., 2014). In demanding work settings, stress can evoke hormonal reactions, impacting cardiovascular and respiratory functions (Vitasari et al., 2010). Job stress is pervasive in contemporary societies, detrimentally impacting mental well-being and contributing to depression and anxiety disorders (Iacovides et al., 2003). Stress is influenced by both work environments and interpersonal dynamics. It is noteworthy that stress-related consequences, including behavioral shifts and reduced performance, establish a cyclic pattern that sustains stress (Okuhara et al., 2021).

2.4. Hypotheses

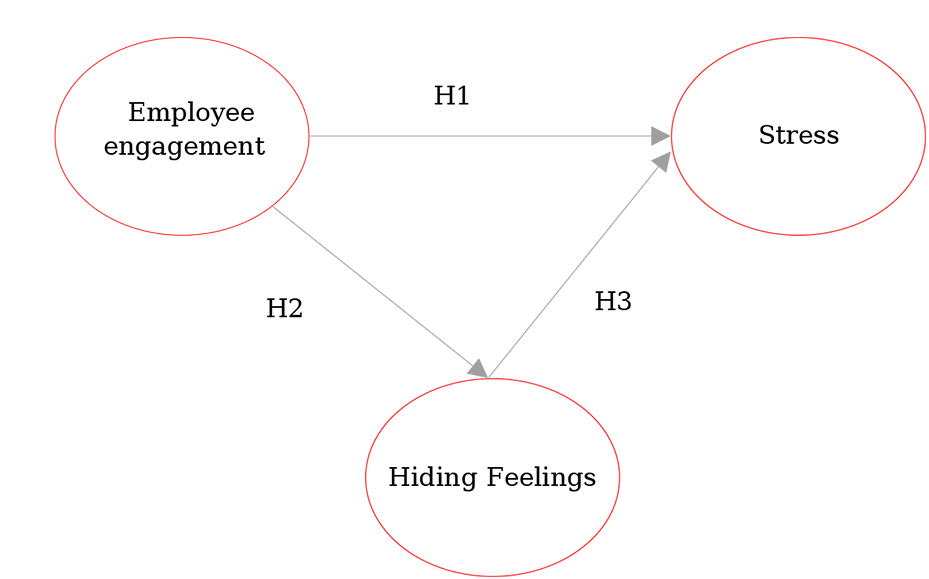

In line with Demerouti et al. (2001) Job Demands-Resources (JDR) model, our investigation delves into the potential for increased employee engagement to alleviate job stress. Rooted in the JDR model’s framework, which posits that job demands and resources can influence employee well-being and performance, we focus on the negative aspects of this model, emphasizing the detrimental effects of job stress (Bakker and Demerouti, 2007; Demerouti et al., 2001a). Building upon previous research by Caesens et al. (2016) and Ravalier (2018), which underscore the positive outcomes associated with high engagement levels, we propose that heightened engagement acts as a buffer against stressors in the work environment. Engaged employees are more likely to perceive their work as meaningful, altering their appraisal of stressors and enhancing their resilience in coping with challenges. Furthermore, heightened employee engagement fosters better coping mechanisms, work-life balance, and organizational commitment (Bakker and Demerouti, 2007; Malik and Garg, 2020). Engaged employees are more inclined to adopt problem-focused coping strategies, seeking solutions to alleviate stressors, rather than succumbing to them (Lee et al., 2023; Kwon and Kim, 2019). Additionally, they are better equipped to manage work demands while preserving their well-being outside of work hours. Thus, we posit a reciprocal relationship between employee engagement and job stress; increased engagement serves as a protective factor against stress. This guides our hypothesis (Figure 1).

H1: Employee engagement is negatively related to job stress.

In various professional sectors such as service, healthcare, and education, emotional labor is widely recognized as a fundamental aspect of job responsibilities. This phenomenon has been extensively studied and documented in literature (Sutton and Rafaeli, 1988; Han et al., 2018; Hochschild, 1983). As individuals immerse themselves in their roles, they often find themselves managing their emotions to fulfill organizational expectations and meet the needs of clients or students. One prevailing idea in the field is that engaged employees, while beneficial to organizations in many ways, may experience pressure to maintain a facade of positivity and professionalism at all times. This pressure can lead them to engage in deep acting, a form of emotional labor where individuals modify their internal feelings to align with external expectations (Sezen-Gultekin et al., 2021; Lee, 2020). However, despite the potential benefits of deep acting, it’s also recognized that there are limits to how much individuals can authentically alter their emotions without experiencing negative consequences.

Accordingly, it can be hypothesized that highly engaged employees may resort to surface acting, which involves the suppression or hiding of true feelings, as a means of coping with the demands of their roles (Vakola and Nikolaou, 2005; Hakanen et al., 2008). This could stem from a combination of factors, including the desire to maintain a positive image in front of colleagues and clients, as well as a strong sense of obligation to the organization. Over time, the continuous use of surface acting as a coping mechanism may lead to emotional exhaustion and burnout (Macey and Schneider, 2008; Halbesleben and Buckley, 2004 ). In light of these considerations, it becomes apparent that exploring the relationship between employee engagement and the tendency to hide feelings is crucial for understanding the dynamics of emotional labor in the workplace. We posit that as employee engagement increases, individuals may be more inclined to engage in surface acting, ultimately leading to a greater propensity to hide their true emotions in the workplace. Thus, based on the existing literature and theoretical frameworks, the following hypothesis is proposed (Figure 1).

H2: Employee engagement is positively related to hiding feelings.

Concealing negative emotions in the workplace is a common phenomenon, often encouraged or enforced by organizational norms and expectations. This aspect of emotional labor, as elucidated in numerous studies (Sieverding, 2009; Brotheridge et al., 2002; Pugliesi, 1999; Zapf et al., 2021), contributes to what psychologists’ term as emotional dissonance-a misalignment between one’s inner feelings and outward expressions. Such dissonance can lead to a myriad of detrimental effects, including heightened stress levels and potential psychological strain.

Extensive research has demonstrated the adverse consequences of hiding negative emotions at work. Individuals who engage in this behavior often report increased levels of stress and experience various emotional repercussions (Bono et al., 2007; Sohn et al., 2018; Zapf, 2002; Mann, 2004 ). The act of suppressing genuine emotions can create a reservoir of internal tension, which, if left unchecked, may manifest in chronic stress and negatively impact overall well-being (Birze et al., 2020; Purper et al., 2023). Moreover, the cumulative effect of engaging in excessive emotional labor, including hiding feelings, has been linked to long-term mental health issues such as depression and diminished psychological well-being (Lee, 2016; Suh and Punnett, 2021). This suggests that the persistent concealment of emotions not only exacerbates immediate stress levels but also poses significant risks to individuals’ mental health over time.

Given the established relationship between concealing negative emotions and adverse outcomes such as stress and psychological distress, it is reasonable to hypothesize a positive association between hiding feelings and job stress. This hypothesis reflects the notion that the more individuals feel compelled to mask their true emotions in the workplace, the higher their levels of perceived stress are likely to be. Thus, based on the existing body of literature and theoretical understanding, the following hypothesis is formulated (Figure 1).

H3: Hiding feelings is positively related to job stress.

Based on the aforementioned, we introduce the conceptual model shown in Figure 1. Our research model explores the mediating role of hiding feelings on employee engagement and stress relationship.

3. Research methodology

3.1. Data Collection and Sampling

The data used for this study were extracted from the Sixth European Working Conditions Survey conducted in 2015. Spanning 35 European Union countries, the survey included translated questionnaires for each country, with nearly 44,000 workers interviewed. Our focus narrowed to the Greek sample, comprising 1,007 observations. The comprehensive questionnaire covered various aspects, including employment status, working conditions, risk factors, health, safety, work-life balance, and more. The surveyed workers, aged 15 and above, encompassed both employees and self-employed individuals from both public and private sectors.

3.2. Measurement Instruments

To evaluate each construct or dimension, we utilized survey questions from Eurofound’s 2015 survey. Our research focuses on three main constructs/dimensions: employee engagement, hiding feelings, and job stress.

3.3. Employee Engagement

In the Eurofound (2016) survey, a concise three-item version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale measured the facets of engagement: Vigor, Dedication, and Absorption. This version has been utilized in various studies (i.e., Breaugh, 2021; Gusy et al., 2019). The survey questions used in our analysis were as follows: Vigor: Q90a - At my work I feel full of energy [Please tell me how often you feel this way...], Dedication: Q90b - I am enthusiastic about my job [Please tell me how often you feel this way...], Absorption: Q90c - Time flies when I am working [Please tell me how often you feel this way...]. All three items were scored from 1 (always) to 5 (never). A one-dimensional engagement factor was derived in our analysis, supported by strong factor loading scores above 0.70 (Table 1). Initial internal reliability statistics indicated good consistency (Cronbach’s α = .739) (Table 2).

Table 1 Engagement factor scores

| Dimension | Engagement |

|---|---|

| Vigor | .829 |

| Dedication | .829 |

| Absorption | .790 |

Source: Authors’ own elaboration.

3.4. Hiding Feelings

In our analysis, we utilized a specific question to gauge hiding feelings, a method employed in prior studies. Wong and Law (2002) and Suh and Punnett (2022) have previously used the same single item to examine emotional suppression’s effects on job stress and burnout. The validity and reliability of this item in measuring emotional regulation have been established in the literature. The question used in our analysis is as follows: Your job requires that you hide your feelings (Scored from 1 [always] to 5 [never]) (Item 61o).

3.5. Job Stress

In this study, employees’ job stress levels were assessed using a single Likert-scale item ranging from 0 (always) to 5 (never). This measurement method, employed in previous research like Langford (2003), is considered a valid measure of job stress. The reliability of this single-question item as an indicator of job stress is supported by studies such as Guinot et al. (2014) and Breaugh (2021). The specific question used in our analysis is as follows: You experience stress in your work? (Scored from 1 [always] to 5 [never]) (Item Q61m).

4. Analysis and results

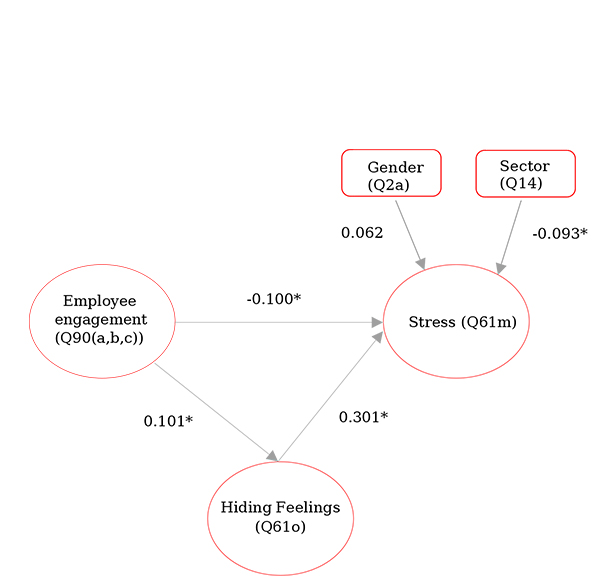

The data analysis was conducted using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), a robust statistical technique for testing complex relationships among variables. By utilizing SEM, our study aimed to validate theoretical models, assess mediation effects, and examine the influence of control variables on the relationships between employee engagement, hiding feelings, and job stress, contributing to a nuanced understanding of workplace dynamics and employee well-being. SEM’s robust statistical framework facilitated objective testing of hypotheses, offering insights into the complex interplay of variables and providing empirical support for theoretical propositions. Detailed descriptions of the SEM methodology will be provided below. The descriptive statistics and correlation factors for the study’s indicators are presented in Table 3. Reliability analysis yields a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.529 (Cronbach, 1951). Job stress is present, with a mean of 2.745, indicating variability among participants. Hiding feelings, with a mean of 2.578, suggests emotional labor to some extent. Employee engagement dimensions show moderate levels: Vigor (Mean = 2.097), Dedication (Mean = 2.322), and Absorption (Mean = 2.201). Participants report some vigor, dedication, and absorption in their work. Correlations reveal a non-significant negative relationship between employee engagement dimensions and stress. However, a significant positive correlation exists between employee engagement dimensions and hiding feelings, indicating that higher engagement relates to a tendency to hide feelings. To empirically validate this research model, we employed structural equation methodology using the EQS 6.4 statistical software. One of the prerequisites for structural equation models is that the observable variables should adhere to a normal multivariate distribution (Batista-Foguet and Coenders, 2000). EQS offers an indicator to assess multivariate normality known as the Mardia coefficient (Mardia, 1970, 1974). However, as our study’s variables did not meet this normality requirement, in line with the recommendations of Hair et al. (2006), we chose to employ maximum likelihood estimation with robust estimators. Consequently, all the χ² values presented in this research correspond to the statistical goodness-of-fit tests developed by Satorra and Bentler (1994). Considering gender and firm sector’s influence on work engagement (Kim and Kang, 2017; Douglas and Roberts, 2020; Agyemang and Ofei 2013) as control variables to take account of the external sources that can affect work engagement, SEM using EQS 6.4 for Windows confirms model fit (Chi-Square = 45.086; df = 13; CFI: 0.955; RMSEA = 0.050) (Table 4). Concerning control variables, gender is chosen as a control variable because previous studies have shown that male and female employees exhibit different levels of engagement (Khodakarami, 2020). Moreover, research suggests that gender influences engagement but may vary depending on the specific work environment and conditions (Shukla et al., 2015). While some studies indicate that female employees tend to be more engaged in their jobs compared to males (Marcus and Gopinath, 2017), others suggest the opposite, highlighting the complexity of the relationship between gender and engagement (Hakanen et al., 2019; Lepistö et al., 2018). Therefore, controlling for gender allows for a more comprehensive understanding of the factors affecting employee engagement. Sector was chosen as a control variable due to its significant impact on employee engagement, as evidenced by various studies. Vigoda-Gadot and Beeri (2012) found that public sector employees exhibit higher engagement levels than those in the private sector. Conversely, Bakker and Hakanen (2013) reported that engagement is lower among public sector employees compared to their private sector counterparts. Further complicating the landscape, Hakanen et al. (2018) observed that the likelihood of work engagement in the private sector is somewhat lower than in other sectors. Additionally, Agyemang and Ofei (2013) demonstrated that private sector employees show higher levels of engagement and organizational commitment than those in the public sector.

Table 3 Research model means, standard deviation and correlation factors (N=976 from 1.007 after excluding missing values)

| Mean | SD | Stress | Hiding Feelings | Vigor | Dedication | Absorption | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stress | 2.745 | 1.070 | 1 | ||||

| Hiding Feelings | 2.578 | 1.359 | 0.2852* | 1 | |||

| Vigor | 2.097 | 0.717 | -0.0559 | 0.1062* | 1 | ||

| Dedication | 2.322 | 0.940 | -0.0081 | 0.0719* | 0.5323* | 1 | |

| Absorption | 2.201 | 0.884 | -0.0400 | 0.0145* | 0.4635* | 0.4649* | 1 |

Notes: *Significant correlation (p < 0.01).

Source: Authors’ own elaboration.

Table 4 Research model: fit indices of the structural equation models

| Model | Chi-square | df | p | BBNNFI | CFI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediated model | 45.086 | 13 | 0.000 | 0.927 | 0.955 | 0.050 |

| Constrained model | 52.91 | 14 | 0.000 | 0.920 | 0.947 | 0.053 |

Source: Authors’ own elaboration.

Regression coefficients show a positive relationship between engagement and hiding feelings (β2 = 0.101; p < 0.05) and hiding feelings and stress (β3 = 0.301; p < 0.01). A significant negative effect is found between engagement and stress (β1 = -0.100; p < 0.05), confirming H1. Gender significantly relates to stress (0.062; p < 0.05), and sector also shows a significant relationship with stress (-0.093; p < 0.05) (Figure 2). Decomposition effects with standardized values indicate an indirect significant effect between engagement and stress (0.030), confirming the mediation effect through hiding feelings. The χ2 test shows a significant difference (p < 0.05) between the mediated and constrained models, evidencing the partial mediation effect of hiding feelings (Beltrán-Martín et al., 2008). Consequently, engagement affects stress indirectly (through hiding feelings), supporting H2 (Figure 2).

5. Discussion

In our comprehensive study utilizing SEM, we delved into the intricate relationships among employee engagement, hiding feelings, and stress within the Greek workforce. Our findings resonate with Cabanas and Illouz (2019), indicating a notable correlation between heightened engagement and an increased inclination to hide feelings, potentially resulting in elevated stress levels. More precisely we found a positive relationship between engagement and hiding feelings (β2 = 0.101; p < 0.05) and hiding feelings and stress (β3 = 0.301; p < 0.01). Furthermore, a significant negative effect is found between engagement and stress (β1 = -0.100; p < 0.05). This nuanced dynamic unveils a potential chain reaction triggered by intense engagement, impacting the mental well-being of employees, and potentially leading to burnout, aligning with Vallerand (2010) on the nature of job passion.

The incorporation of control variables, specifically gender and sector, revealed significant relationships with stress. Therefore, controlling for these variables provides a more comprehensive understanding of the factors affecting employee engagement. Gender-related findings indicated significant variations in stress levels, with females tending to experience higher stress compared to males (0.062; p < 0.05). This aligns with Sieverding’s (2009) observations on the propensity to conceal emotions and its diverse impacts on mental health. Additionally, the sector variable revealed industry-specific factors influencing stress levels, with individuals in the private sector experiencing higher stress compared to those in other sectors (-0.093; p < 0.05). These divergent findings highlight the necessity of controlling for sector differences to accurately assess employee engagement and emphasize the need for tailored approaches to address sector-specific challenges. This discrepancy may stem from factors such as job insecurity, fierce competition, long working hours, and pressure to meet financial targets. Conversely, sectors such as the public sector, joint private-public organizations, not-for-profit organizations, and others may offer distinct work environments or organizational cultures that alleviate stressors commonly encountered in the private sector. Our research meticulously explores the intricate relationship between engagement and stress, unveiling a significant indirect effect that highlights the pivotal role of hiding feelings as a mediating factor. Through a thorough comparative analysis of mediated and constrained models, our study reveals a nuanced understanding, emphasizing that the suppression of emotions partially mediates the complex relationship between engagement and stress, accentuating the interplay between these factors and the concealment of feelings. The significance of our research within the existing literature is noteworthy, challenging the prevailing negative relationship between work engagement and job stress. Our investigation introduces a crucial nuance by incorporating the mediation variable of hiding feelings, resulting in a reduction of the relationship’s significance. This unveils a more intricate connection, where individuals with high levels of work engagement may hide their feelings, potentially leading to increased stress levels. This insight adds depth to the understanding of the interplay between work engagement and job stress, underscoring the importance of considering additional factors such as emotional expression in comprehending the complexities of this relationship.

In conclusion, our research not only illuminates the darker aspects of heightened employee engagement but also underscores the potential risks and challenges that organizations must navigate. The incorporation of control variables enriches the dynamics, emphasizing the need for personalized strategies to enhance job satisfaction and efficiently manage stress. This subtle understanding urges organizations to adopt a more balanced approach to employee engagement, aligning with the advocacy of well-being alongside productivity, as proposed by Cooper et al. (2001). Furthermore, our study not only enhances understanding but also serves as a catalyst for future research on global work engagement variations and post-pandemic considerations. The inquiry raises pertinent questions about the impact of HRM systems, aligning with Cooper and Marshall’s call for research into adverse facets (1976).

While acknowledging the limitations of our study, including SEM-related risks, a Greece-centric focus, and omitted variables, we emphasize the importance of a cautious interpretation (Stansfeld et al., 1999). The study’s comprehensiveness may be constrained, and gender-related findings lack nuance due to our cross-sectional design, highlighting the potential benefits of adopting a longitudinal approach.

6. Conclusions

This research has brought to light a compelling connection between heightened employee engagement, the tendency to hide feelings, and increased stress levels within the Greek workforce. This revelation underscores the imperative for organizations to adopt a holistic and balanced approach that places a premium on employee well-being in tandem with productivity goals.

The significance of our findings extends beyond immediate implications for organizational management; they also contribute valuable insights to the broader field of management literature. By emphasizing the importance of employee well-being, organizations can not only enhance job satisfaction but also cultivate healthier work environments.

From a management perspective, our study suggests several actionable strategies. First, organizations should prioritize creating a supportive environment that encourages open emotional expression and reduces the stigma associated with sharing personal feelings. This can be achieved through training programs aimed at enhancing emotional intelligence and communication skills among employees and managers.

Second, implementing comprehensive employee wellness programs that address both physical and mental health can mitigate stress levels and improve overall well-being. These programs might include stress management workshops, access to mental health resources, and initiatives promoting work-life balance. Third, organizations should consider revisiting their Human Resource Management (HRM) systems to ensure they are aligned with employee well-being goals. This may involve incorporating well-being metrics into performance evaluations and fostering a culture of recognition and support. Additionally, our findings highlight the need for tailored management practices that consider cultural nuances. Cross-cultural examinations can provide deeper insights into how employee engagement, emotional concealment, and stress manifest in different cultural contexts, informing more effective and culturally sensitive management strategies. The evolving landscape post-pandemic presents an opportune time for comprehensive studies on work engagement, considering the lasting impacts of the global crisis on the workforce. Future research could explore how remote work, hybrid models, and changes in workplace dynamics influence employee engagement and well-being.

In laying the groundwork for future research, our study underscores the need for continuous exploration and evaluation of workplace dynamics. By emphasizing the importance of employee well-being, organizations can enhance job satisfaction, reduce turnover, and foster a more productive and positive work environment.