Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Praxis Filosófica

versión impresa ISSN 0120-4688versión On-line ISSN 2389-9387

Prax. filos. no.43 Cali jul./dic. 2016

PRACTICAL REASON, HABIT, AND CARE IN ARISTOTLE1

Racionalidad práctica, hábito y cuidado en Aristóteles

Juan Pablo Bermúdez

Profesor del departamento de filosofía de la Universidad de Externado de Colombia, Medellín, Colombia. Ph.D en filosofía por la Universidad de Toronto. Realizó estudios de maestria en filosofía en la universidad nacional de Colombia. Sus principales áreas de trabajo y de investigación son la filosofía de la mente y la filosofía antigua.

Dirección Postal: Universidad Externado de Colombia, Facultad de Ciencias Sociales y Humanas. Calle 12 No. 1-17 Este. Bogotá, Colombia.

Dirección electrónica: juan.bermudez@uexternado.edu.co

Recibido: octubre 25 de 2015

Aprobado: enero 22 de 2016

Abstract

Interpretation of Aristotle's theory of action in the last few decades has tended toward an intellectualist position, according to which reason is in charge of setting the goals of action. This position has recently been criticized by the revival of anti-intellectualism (particularly from J. Moss' work), according to which character, and not reason, sets the goals of action. In this essay I argue that neither view can sufficiently account for the complexities of Aristotle's theory, and propose an intermediate account, which I call indirect intellectualism, that preserves the merits of both traditional interpretations and is able to dispel the problems that trouble each. There is very strong textual evidence for the claim that goal-setting is the task not of reason but of character (and in this anti-intellectualists are right); but reason is able to set goals indirectly by carefully shaping the processes of habituation that constitute a person's character (and in this intellectualists are right). I argue for this position through a study of the division of labour between character and reason, and through a reconstruction of Aristotle's conception of habituation.

Keywords: action; control; habit; reason; care.

Resumen

En las últimas décadas, la interpretación de la teoría de la acción de Aristóteles ha tendido hacia una postura intelectualista, según la cual la razón está a cargo de establecer los fines de las acciones. Un resurgimiento del anti- intelectualismo, según el cual establecer los fines es tarea del carácter y no de la razón, ha puesto esta postura bajo crítica (particularmente de la mano de J. Moss). Este ensayo sostiene que ninguna de las dos interpretaciones puede dar cuenta suficiente de las complejidades de la teoría de Aristóteles, y propone una postura intermedia, que llamo intelectualismo indirecto, que preserva los méritos de ambas interpretaciones tradicionales y a la vez logra disipar los problemas que aquejan a cada una. Existe muy sólida evidencia textual a favor de la tesis según la cual establecer fines es tarea no de la razón sino del carácter (y en esto los anti-intelectualistas están en lo correcto); pero también es necesario reconocer que la razón puede establecer fines indirectamente, a través del cuidado de los procesos de habituación que constituyen el carácter de una persona (y en esto los intelectualistas están en lo cierto). Defiendo esta interpretación a través de un estudio de los pasajes que señalan una división del trabajo entre el carácter y la razón, y de una reconstrucción de la concepción aristotélica de la habituación.

Palabras clave: acción; control; hábito; razón; cuidado.

For me, running is both exercise and a metaphor. Running day after day, piling up the races, bit by bit I raise the bar, and by clearing each level I elevate myself. At least that's why I've put in the effort day after day: to raise my own level. I'm no great runner, by any means. [...] But that's not the point. The point is whether or not I improved over yesterday. In long- distance running the only opponent you have to beat is yourself, the way you used to be.

-H. Murakami: What I talk about when I talk about running

Introduction: the problem of goal control

In everyday life we usually assume that we are agents, i.e. that we are autonomous beings who not only react, like rocks or H2O molecules, but act and can somehow determine their own fate. But this assumption becomes quite confusing once carefully examined. To begin, consider the definitional issues: what is an action?, and what makes beings like us agents? It has recently been suggested that we can call ourselves 'agents' insofar as we control our behaviour, and that an agent's behaviour counts as an 'action' only if the agent was in control of its production.2 Control-based accounts of intentional action are not new, however. Arguably, Aristotle already endorsed a version of it. He does, in fact, claim that we are in control (or kurioi) of our actions.3 Since the control-based accounts are experiencing a resurgence, it is now worth asking how Aristotle conceived of practical control.

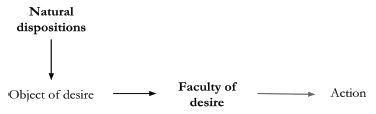

In Aristotle's conception of basic, animal agency,4 actions are understood as locomotions that originate in the animal's inner principles; those inner principles are (1) the animal's faculties of cognition, desire, and motion; and (2) the animal's natural dispositions to perceive some things as pleasant and others as painful (see Fig. 1.1). Animals have different cognitive capacities, which include different perceptual senses and diverse capacities of phantasia (roughly, a capacity to imagine previously perceived objects even when they are not perceptually present).5 They also have different capacities for desire (some can desire only immediate satisfactions; others can desire more distant and complex objects). These cognitive and volitional capacities put together constitute a functional unit-which Aristotle calls the "faculty of desire"-that allows the animal to pursue the good and flee from the bad. Thus, when the animal's natural dispositions makes something appear good or bad, the animal appropriately pursues or flees from it.

In this model, animal action has one great limitation: the animal is said to act insofar as it controls the behaviour it produces in response to an appearance of some object as pleasant or painful; but it cannot control what appears pleasant or painful to it. This is largely established by nature:

One half of [animal] life consists in the activities of procreation, and the other in the activities related to nutrition; for all their efforts and their way of life happens to revolve around these two. [...] And what is in accordance with nature is pleasant; and each animal pursues that which is pleasant in accordance with nature (History of Animals [HA] VIII.1 589a2-9)

The apparently pleasant object is the animal's goal, i.e. that for the sake of which it moves. So animals are not in control of their goals. What about humans, then? Are we in control of our goals, and if so, how do we establish them? Interpreters have answered this question it two main ways. Intellectualists hold that human agents establish their goals by means of reason [logos] and reasoning [logismos]; whereas anti-intellectualists claim that the goals of a human's life are established by her character, and reasoning has no role in the goal-setting process.6

Figure 1.1: The structure of animal agency. (The inner principles of animal action are in bold font.)

I argue in what follows that neither of the two views manages to account for Aristotle's particular take on goal control. Against intellectualism, there is plenty of textual evidence that shows logos cannot establish the goals of action; and against anti-intellectualism, if reason had nothing to do with goal-setting, then why would Aristotle have written ethical treatises, which are a long rational discussion on the goals of life? Given that both traditional positions are untenable, I defend the view I call indirect intellectualism. The two main claims of indirect intellectualism are the following:

- Reason can determine the goals of action only indirectly, by caring for the agent's character.

- An individual agent's ability to care for her own character depends on political institutions of public care.

- Since the problem with traditional intellectualism is that it assumes reason can set an individual's goals directly, by reasoning alone, I argue that reason sets goals only through habituation, the character- shaping process. And Aristotle further claims that care for character development should be a mainly political task, so I argue that individual reason depends on public structures of public rationality.

I proceed as follows: The first section briefly presents the evidence against the traditional intellectualist view; the second section argues for thesis (i) of indirect intellectualism. Given limitations of space, I must leave thesis (ii) for another occasion.

Reason cannot set the agent's goals

In this section I (1.1) distinguish the functions that intellectualists attribute to practical reason, and then argue that (1.2) character, and not practical reason, establishes the goals of action. This view is strengthened by (1.3) Aristotle's explicit claims on the issue of goal-setting.7

1.1. The functions of practical reason

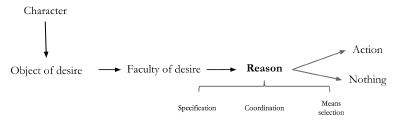

Any account of the role of reason in action production must take to two striking features of Aristotle's psychology under account: first, he divides the human soul into non-rational and rational parts, the former associated with character and capacities we share with animals, the latter allowing for calculation- and deliberation-dependent activities and dispositions (e.g. EN I.13). And second, he claims that the irrational part determines the goals of action, whereas reason is in charge only of establishing "the things toward the goal". The diverse views of practical reason's function stem from the interpretation of the phrase "things toward the goal", which specifies reason's realm of operation in action production. The most restrictive interpretation takes the phrase "things toward the goal" to be equivalent to "means". In this reading, reason would have a purely instrumental function, and would therefore be unable to set goals.8 However, if "things towards the goal" is taken to include not just means, but also other things necessary for complex goal pursuit, other interpretive possibilities open up.

Specification intellectualism - An influential interpretation holds that the goals that character specifies are rather abstract (e.g. 'the fine' or 'the noble'), and thus reason must get involved to determine what counts as attaining the goal in each practical situation (what counts as a fine and noble action in this particular context). Practical reason's function is thus specificatory: deliberation establishes means to achieving the goal, but must previously determine the goal's specific content.9

Coordination intellectualism - Another possible interpretation is that reason is in charge of assessing whether the currently active goal is in accordance with broader considerations. This may include assessing whether the goal fits with one's overall conception of the good, or whether it is preferable to currently competing goals. If reason determines that a given end is not in accordance with one's practical concerns, then it can reject it, and decide on a different path of action. This interpretation gives reason a coordination role, which allows the agent to lead a consistent and unified life, responsive to the broader goals that character purportedly establishes, mainly by evaluating each apparent good, and rejecting or postponing it whenever necessary. Thus, "the eligibility of a target in context is tested by deliberation".10

Although interpreters argue about which of these interpretations of Aristotelian practical reason is correct, I need not choose between them here, for two reasons. The first is that they are not incompatible. In fact, a thorough intellectualist could attribute both goal-setting functions to reason, which would go something like this. In non-human animals, the appearance of an object as good or bad immediately generates a desire, and desire leads immediately and invariably to action; but in humans the capacities for rational calculation (logismos) and deliberation (boulē) stand in between desire and action (see Fig. 1.2), making it possible for the agent to exert more control by specifying what the good is in each occasion; by coordinating goals with one another; and by allowing the agent to not act even in the presence of an apparent good.

Figure 1.2: The intellectualist interpretation of the structure of human agency.

1.2. The division of labour between reason and character

So intellectualists hold that reason determines the goals of action by specifying and coordinating them. But the two peculiarities of Aristotle's moral psychology mentioned above (the distinction between the soul's rational and non-rational parts, and the division of labour between them) suggest that reason cannot set the goals of action. Reason's specification and coordination functions are but applications of deliberation and calculation, i.e. of logismos; but I show in what follows that several lines of textual evidence show that logismos cannot establish the goals of action: (1.2.1) we cannot arrive at practical reasoning's starting points through reasoning; (1.2.2) deliberation is not about goals, but only about things toward the goals; and (1.2.3) goals are determined not by reasoning, but by habit and character.

1.2.1. There is no reasoning of "starting points"

Consider Aristotle's claim that there is no logismos of the starting points of reasoning:

Does virtue produce the goal (τ?ν σκοπ?ν), or the things toward the goal (τ? πρ?ς τ?ν σκοπ?ν)? We posit that the goal, because there is no argument (συλλογισμ?ς) or reasoning (λ?γος) of it. Rather, it must be presupposed like a starting point. For neither does the doctor investigate whether to heal or not, but whether to take walks or not; nor does the athlete [investigate] whether to be in shape or not, but whether to wrestle or not. Likewise, no other [science] reasons about the goal; for just like in the theoretical [sciences] the hypotheses are starting points, equally also in the productive [sciences] the goal is a starting point and a hypothesis. [...]

Thus, the starting point of thought (τ?ς νο?σεως ?ρχ?) is the goal, and the starting point of action is the end-point of thought. Therefore, if either vir- tue or reason is the cause of all correctness, and reason is not the cause, then virtue will be the cause of the goal's correctness, but not of the correctness of the things toward the goal. (EE II.11 1227b22-30 ... 32-36)

The latter remarks fit nicely with the intellectualist view in the sense that reason is portrayed as standing between the goal and the action. However, such intermediary role also implies that reason is not in control of its own starting point, i.e. the goal. Just like axioms in geometry, practical reason must accept the goal as a hypothesis, and operate on those hypothetical grounds, because reasoning cannot produce its own starting point in the practical realm either.

1.2.2. Deliberation is not about the goals

Which is why, as Aristotle goes on to argue, decision (prohairesis) is only about things toward the goal, but never about the goal itself.11 This is because decision is the product of deliberation,12 and deliberation itself can determine only the things toward the end, not the end itself:

We deliberate not about the goals but about the things toward the goals (τ?ν πρ?ς τ? τ?λη). For neither does the doctor deliberate whether to cure, nor does the orator whether to persuade, nor does the politician whether to make good laws, nor do people deliberate about the goal in the other cases; but having posited the goal they investigate the 'how' and the 'throu- gh what' it will come to be ( θέμενοι τὸ τέλος τὸ πῶς καὶ διὰ τίνων ἔσταισκοποῦσι). (EN III.3 1112b11-16)13

So there is no reasoning about the starting points of practical reasoning, i.e., the goals; and consequently deliberation, i.e. practical reasoning, is about the things toward the ends rather than about the ends themselves. Thus, whatever the "things toward the goals" are, the goals themselves are relevantly prior to them, determined by means other than reasoning.

So how are goals determined, if not by reasoning?

1.2.3. Habituation determines the goals

First, as we have already seen, Aristotle mentions "virtue of character" rather than reason or thought as responsible for correctly establishing the starting points. We should see character, rather than virtue, as the crucial factor in goal-setting: although the virtuous character makes a person's goals right, it is character, virtuous or not, that sets goals. So how is it that an agent's character determines her goals?

A crucial part of the answer is Aristotle's claim that virtue of character is about pleasures and pains.14 As seen above, an animal's natural intuitions are given to it from birth and quite rigidly determine their practical perception (i.e. the tendencies for some things to appear pleasant and some things painful via their perception and phantasia). Contrastingly, human innate dispositions are much less definitive. This is not to say that our practical perception is a blank slate: our initial natural dispositions are quite similar to those of other animals. But a crucial difference is that our practical perception can be largely re-shaped through habituation; so we find pleasure or pain in the things that we get used to finding pleasure or pain in.

It is worth clarifying that Aristotle does not consider animals to be devoid of all habituation capacities. His view is rather that "the other animals live mostly by nature, and some only few times by habits (τὰ μὲν οὖν ἄλλατῶν ζῴων μάλιστα μὲν τῇ φύσει ζῇ, μικρὰ δ’ ἔνια καὶ τοῖς ἔθεσιν)”)" (Pol. VII.13 1332b3-4). We share these initial dispositions with animals, to the point that Aristotle claims the souls of children "do not differ at all, so to speak", from the souls of animals (HA VII.1 588a32-b2), and is prepared to attribute phronēsis and other virtue-related terms to animals that display exceptional intellectual capacities.15 But he seems to think that animals by and large need not develop habits, probably because their natural dispositions provide them with sufficient cognitive adaptation to their environments.16 Human innate dispositions, on the other hand, are quite deficient: we are born less hard-working and more pleasure-loving than we should be; and although we have innate predispositions toward acquiring virtue, such predispositions are actually dangerous without the proper cognitive development.17

This is why we need habituation processes that build our character and at the same time shape our appearances of the good, therefore broadly establishing our goals: which objects appear pleasant and worth pursuing, and which appear painful and avoidable. A proper habituation will lead to the correct starting points (i.e. an appearance of the good that coincides with what truly is good); any other habituation will lead to incorrect starting points (EN III.4). Thus the character we have developed turns out to establish the principles of our action: our cognitive reactions to the practical world.

Moreover, habituation not only establishes our goals by moulding our practical perception. It also determines in which situations, and to what extent, we are willing to use reasoning and attend to arguments. This reveals that for Aristotle the use of practical reason is not a trait all humans share, but one proper only to the humans that have been properly habituated.

Reason and teaching certainly do not have strength in everyone; rather, the listener's soul must have been prepared with habits to be pleased and suffer finely, just like soil that is to nourish the seed. For he who lives in accor- dance with passion would not listen to reason, and would turn away from it-he would not even understand it. And how could a man with such dis- position change his persuasion? He does not seem to yield at all to reason, but to force. So it is necessary that a character pre-exists that is somewhat familiar to virtue, that loves the fine and is displeased by the ugly. (EN X.9 1179b23-31; cf. Topics [Top.] I.11 105a2-7)

Thus, character determines not only which things one loves and hates, but also whether one is capable of listening to the voice of reason. Aristotle refers to this also to argue that not everyone can be a good student of politics: immature people, who live by their passions, lack the experience that is necessary to turn reasoning into action.18

In sum, there are at least three strong lines of evidence suggesting that reason cannot set a person's goals: the starting points of practical reasoning cannot themselves be obtained by reasoning; practical reasoning (i.e. deliberation) is not about the goals, but only about the things toward the goals; and our phantasiai of the good are set by the habituation processes that constitute our character. Moreover, as I will show now, Aristotle's explicit claims on the issue make it even clearer that reason does not set goals.

1.3. Aristotle's solution to the problem of goal control

During his Nicomachean discussion of action (EN III.5), Aristotle addresses an opponent who contends that while virtuous people are voluntarily virtuous, no one is voluntarily vicious.19 The beginning of this intricate passage makes it clear that there is a lot at stake in the issue: if it cannot be demonstrated that vice is voluntary, "we should not say that man is a principle or that he is the generator of his actions" (1113b17-19). In other words, unless it can be shown that virtuous people are voluntarily virtuous and vicious people are voluntarily vicious, the very claim that we are in control of our actions is falsified. Aristotle is probably led to making such claim given the tight causal connection between actions and character: a certain character begets actions of a certain kind (1114a11-18), and the principles of our actions, i.e. the appearances of the good, are determined by character (1113a30-31).20 Aristotle presents the opponent's argument:

Now, if someone said that everyone pursues the apparent good, and we are not in control of phantasia but rather the end will appear to each one in accordance with the sort of person that he is, [...]21 no one would be responsible (α?τιος) for his own bad actions, but rather each one would do what he does due to ignorance of the goal, believing because of it that what he does is the best for himself. And the aim for the goal would not be self-chosen ( ἡ δὲ τοῦ τέλους ἔφεσις οὐκ αὐθαίρετος); instead, one would need to have been born with a natural sense of sight that allowed one to discern finely and choose what is truly good. And he who has this sense in a fine condition by birth is a good-natured man. (EN III.5 1114a31-b5)

Taking 'φαντασία' and 'φαινόμενον ἀγαθόν' in the technical sense (i.e. as referring, respectively, to the faculty of phantasia, and to the appearance of the good that such faculty generates), the objection can be reconstructed as follows:

- Our phantasia of the good is determined by the sort of person that we happen to be.

- It is not up to us to be the sort of person we happen to be.

- Therefore, our phantasia of the good is not up to us. [I, II]

- So if someone has the wrong phantasia, she will act badly, and not voluntarily. [III]

- Therefore, no one is voluntarily vicious. [IV]22

The opponent's position has an interesting positive flipside: because we are the kind of person that we (naturally) turn out to be, our phantasia of the good is not up to us, but up to nature. So if we end up performing wrong actions, it is because we have the wrong phantasia, and this in turn is due to our being bad-natured. On the other hand, those who have the correct phantasia are in a way naturally blessed, born with a special sense of practical perception that provides them with the right discernment. For the rest of us, we can at least rest content in that our errors are not up to us, but rather caused by an unavoidable natural imperfection: we were just born that way!23

Aristotle could reply to the objection by rejecting either (I) or (II). If he held an intellectualist view, one would expect that he replied either of these claims:

(I*) Our phantasia of the good is determined by reason.

(II*) We can determine the kind of person we are through the exercise of reason.

But Aristotle replies to the objection by arguing neither for I* nor for II*: this passage contains no hint of the claim that logos or logismos can determine a person's phantasia or character. In fact, no word related to reason appears anywhere in his reply. Aristotle does reply by rejecting (II), but in the way that an anti-intellectualist would expect:

Now, if someone said that everyone pursues the apparent good, and we are not in control of phantasia but rather the end will appear to each one in accordance with the sort of person that he is-actually, [we should reply that] if each one is in a sense the cause of his own character, he will also be in a sense the cause of his phantasia ( εἰ μὲν οὖν ἕκαστος ἑαυτῷ τῆς ἕξεώςἐστί πως αἴτιος, καὶ τῆς φαντασίας ἔσται πως αὐτὸς αἴτιος). (1114a31-b3)

I translate the word aitios here as 'cause' to highlight the causal aspect of the claim, but it could also be translated as 'responsible' or 'accountable': you are accountable for your appearance of the good because, and insofar as, you are accountable for your own character [hexis].24

Action control depends on careful habituation

So we control our actions only insofar as we are causes of our phantasia of the good, and we are causes of our phantasia only insofar as we are causes of our character. But how are we causes of our character? In this section I answer this question by (2.1) exploring the mechanism of habituation, and (2.2) arguing that we can control our actions only insofar as we carefully shape our character through habituation.

2.1. How habituation works

The notion of habituation is deceptively simple: according to Aristotle, we become habituated into feeling pleasure and pain in relation to the right things simply by repeatedly performing the right actions (EN II.1). So habituation seems to be a merely mechanical process of repetition. If it is, then it seems unable to explain the generation of the complex cognitive capacities and dispositions of adult virtuous life (like good deliberation and phron?sis). Because the process of repetition-based habituation seems too mechanical to account for intellectual development, some scholars have added a conceptual or intellectual element to their description of habituation, which makes habituation consist not only in repeating certain tasks and developing certain dispositions, but also in dialectical training grounded on exhortation and advice. Habituation would thus yield correct beliefs about the fine and the noble, and an implicit conception of the human good, which can be made explicit by the study of ethics.25

I will argue that it is not necessary to intellectualize habituation in order to account for cognitive development. First, Aristotle's discussions of habit and habituation do not explicitly mention intellectual or conceptual elements, but only repetitions of actions, so any addition of intellectual elements lacks textual support. Furthermore, if understood correctly, a non-intellectual account of habituation is sufficient to explain how we develop the proper intellectual capacities that ultimately lead to complex adult agency.

I construct an account of habituation by looking first at the relationship between habit and nature, and then at how exactly it is that mere repetition alters our phantasia of the good. I argue that (2.1.1) habit is an artificial inner causal principle that extends natural practical capacities; (2.1.2) and it achieves such extension because through repetition we become able to endure affections and activities that we are initially unable to endure. This account can explain how the proper habituation makes us able to engage in, and even enjoy, the effortful activities that ultimately lead to the virtues.

2.1.1. Habit as an extension of nature

This is one of Aristotle's descriptions of habituation:

Character ( τὸ ἦθος), as its name indicates, is that which grows out of habit ( ὅτι ἀπὸ ἔθους ἔχει τὴν ἐπίδοσιν), and something is habituated when, after having been repeatedly moved in a certain way by non-innate training, it is eventually capable of being active in that way (ἐθίζεται δὲ τὸ ὑπ’ ἀγωγῆςμὴ ἐμφύτου τῷ πολλάκις κινεῖσθαι πώς, οὕτως ἤδη τὸ ἐνεργητικόν). (EE II.2 1220a39-b3)

According to this, habits have a causal power: through repetition an agent becomes able to perform a non-natural pattern of activity without external enforcement. The principle that originally accounts for the agent's activity is external to the agent, but through habituation said principle becomes internal. The activity thus quite literally becomes 'second nature': an artificial inner principle of movement.

Habits also have cognitive and motivational aspects, because habituation makes things appear pleasant or painful: "The things that are customary and acquired by habit are also among those that are pleasant-Aristotle says in the Rhetoric-; for many among the things that are not naturally pleasant produce pleasure when people have become habituated to them."26 The discussion of human sexual development exemplifies both causal and cognitive aspects of habit:

[The impulse of the young] towards sexual activities is strongest when they begin, so that if they do not take care to avoid causing further movement (beyond the changes that their bodies themselves make, even without se- xual activity) it follows that they become habituated ( εἴωθεν) in their later life. For the females who are sexually active while quite young become more intemperate, and so do the males if they are unguarded either in one direction or in both. For the channels become dilated and make an easy passage for fluids in this part of the body; and at the same time their old memory of the accompanying pleasure creates desire ( τότε μνήμη τῆςσυμβαινούσης ἡδονῆς ἐπιθυμίαν ποιεῖ) for the intercourse that then took place. (HA VII.1 581b11-21; cf. Pol. VII.16 1334b29-1335a35)

The passage makes clear that through repetitions of (both physical and mental) activity we generate habits that shape not only our bodies and their subsequent motions-the account tells of passages becoming dilated and fluids flowing more easily-, but also our cognitive and motivational dispositions, i.e. our tendencies to perceive and remember things as appealing or unappealing, and therefore to generate desires towards them. Thus, habit is an extension of nature because, by repeating activities of a certain kind, we create new patterns of practical cognition and motivation, which were not innately established (e.g. if we repeatedly engage in sexual intercourse, we subsequently desire sexual intercourse even more than was innately determined).

2.1.2. Repetition, endurance, and pleasure

How is it that mere repetition of actions can shape our cognitive and motivational dispositions toward feeling pleasure and pain? This is the core problem of habituation: repetition seems to be a purely mechanical process, so it is not clear what cognitive value it may have. How can we move from mechanical iteration to cognition and motivation? Luckily, Aristotle answers this question explicitly.

The first step toward an answer is understanding the link between what is natural and what is pleasant. Recall that "what is in accordance with nature is pleasant" (HA VIII.1 589a2-9). Aristotle further develops this idea in the Rhetoric, where he makes a taxonomy of pleasant things. The list starts with natural things: "What for the most part leads toward what is according to nature is necessarily pleasant, and most of all whenever the beings that are according to nature recover their own nature".27 But natural things do not exhaust the class of pleasant things. Aristotle adds two more items:

καὶ τὰ ἔθη (καὶ γὰρ τὸ εἰθισμένον ὥσπερ πεφυκὸς ἤδη γίγνεται· ὅμοιον γάρτι τὸ ἔθος τῇ φύσει· ἐγγὺς γὰρ καὶ τὸ πολλάκις τῷ ἀεί, ἔστιν δ’ ἡ μὲν φύσιςτοῦ ἀεί, τὸ δὲ ἔθος τοῦ πολλάκις), καὶ τὸ μὴ βίαιον (παρὰ φύσιν γὰρ ἡ βία,διὸ τὸ ἀναγκαῖον λυπηρόν [...])

Also habits [are necessarily pleasant], for what has been habituated already occurs just like what is natural, because habit is something similar to nature ( ὅμοιον γάρ τι τὸ ἔθος τῇ φύσει); in fact, what occurs repeatedly is akin to what occurs always, and while nature is among the things that occur always habit is among those that occur repeatedly. And what is not forced ( τὸ μὴ βίαιον) [is necessarily pleasant], for what is forceful is against nature, which is why things that are necessary are painful [...] (1370a5-10)

27 ἀνάγκη οὖν ἡδὺ εἶναι τό τε εἰς τὸ κατὰ φύσιν ἰέναι ὡς ἐπὶ τὸ πολύ, καὶ μάλιστα ὅτανἀπειληφότα ᾖ τὴν ἑαυτῶν φύσιν τὰ κατ’ αὐτὴν γιγνόμενα[.] (Rhet. I.11 1369b33-1370a5)This passage confirms the nature-habit analogy, and builds an overall picture of the things that are pleasant, dividing them into three groups: what is natural (because it restores a natural state), what is habitual (because habit works in a way analogous to nature), and what is not forced (because what is forced is opposed to what is natural). The third group actually includes the other two, which entails that anything that is not against nature (i.e. forced) is pleasant.28

This is the first element required to answer our question (how can mere repetition alter cognitive dispositions?). The second element is that, although those things that are not against nature are pleasant, they are pleasant only to a degree. Eating and drinking, for instance, are pleasant until you are filled, and after a certain point those activities can become quite unpleasant. Similarly, we enjoy physical and cognitive activities (like walking or running, learning or contemplating) only until we get tired.29

This is where repetition comes in: repeating the same activity multiple times increases our capacity to endure its performance, thereby making us able to enjoy its performance for longer periods. This is explicitly clear in Aristotle's reply to one of the Problems concerning food, which is worth quoting in some length:

Why do the same things appear pleasant ( ἡδέα φαίνεται) to those habituated [to them], but do not appear pleasant to those who take them in too con- tinuously? (And 'habit' is doing something repeatedly and continuously.) Is it perhaps because habit produces in us a certain receptive disposition ( ἕξιν δεκτικήν), but not satiety, whereas continuously consuming some- thing satiates the appetite? For appetite also is something [like this]. Thus dispositions, when trained ( γυμναζόμεναι), grow and increase; but vessels do not become larger by getting filled up. Hence habit, being an exercise ( ὂν γυμνάσιον), increases the receptive disposition [...].

Further, habit is pleasant not in the sense that it always is pleasant (for even these things [i.e. habitual things] are painful, if they are done continuous- ly), but rather in the sense that we receive the begining of the activity with pleasure, and are able to do the same thing for a longer time than if we were not habituated ( πλείω χρόνον δύνασθαι ταὐτὸν ποιεῖν ἢ ἀσυνήθεις ὄντας).

In that sense, then, things produce pain even though they are pleasant [...]. The cause is that our own receptive and productive capacities are not unli- mited, but limited; and when they come across something that is commen- surate with them (one can indeed continuously and increasingly percei- ve this), some of them get satiated, and the others are unable to function. (Prob. XXI.14 928b23-929a5)

Thus, given the limitations of our capacities for receiving affections and producing actions, we find pleasure in affections and activities only until these capacities are exhausted. But habit extends our natural capacities by increasing our receptive dispositions. By repeating an activity we exercise ourselves in its performance, we build up our endurance of this activity- much like a runner builds up endurance while training for a marathon, or someone who regularly eats spicy food develops a resistance for spices. This 'gymnastic' aspect of habit is crucial for understanding its role in both moral and cognitive development.

Crucially, habit does not seem to make us enjoy things that we did not at all enjoy before-i.e. we cannot habituate ourselves into things that are forced and go against our inner principles of action. What habit does do is allow us to extend our natural pleasures by extending the amount we can receive of the pleasant thing before it becomes painful, or extending the amount of time we can perform an action before we get too tired and have to take a break. Virtuous life is like a long marathon, and proper habituation is like the daily training routine that builds the resistance needed to reach the end of the race without hitting a wall of exhaustion.

We initially have a tendency to avoid hard work, and to excessively enjoy easy and immediate pleasures. So proper habituation is necessary to develop the right moral and cognitive dispositions that originate virtue. This is because by exercising the correct rational activities, we become more able to endure them, and to enjoy them for longer periods. This is how non-intellectual habituation sufficiently explains moral and cognitive development.

2.2. Care for habits is necessary for agentive control

Back to the open question: EN III.5 claims that we are in control of our actions because we are (in a sense) the causes of our phantasia, and that we are causes of our phantasia because we are (in a sense) the causes of our character. So in what sense are we causes of our character? To find the answer, we must go back to the debate with the anonymous opponent in EN III.5.

Immediately after introducing his opponent's thesis (i.e. that no one is voluntarily vicious), Aristotle begins his refutation (1113b21-30) by claiming that everyday social practices presuppose that we are in control of our actions: we all praise and blame, reward and punish each other for actions we perform-all of which would make no sense if external principles determined our actions. He further adds that everyday legal practices show people being held responsible even for things they do in ignorance (1113b30-1114a3); e.g. if someone did something in ignorance because he was drunk, he gets twice the punishment. This practice-he thinks-reveals that those who seem to ignore things "due to lack of care ( δι’ ἀμέλειαν)" are accountable for their actions, because not ignoring it was up to them; since "they were in control of caring ( τοῦ γὰρ ἐπιμεληθῆναι κύριοι)."

Now that Aristotle has introduced the notion of care, the opponent strikes back, challenging the very idea that everybody is in control of caring, of being careful:

-"But perhaps he is the sort of person who would not be careful! ( ἀλλ’ἴσως τοιοῦτός ἐστιν ὥστε μὴ ἐπιμεληθῆναι)" (1114a3-4)

This remark, laconic as it is, makes a lot of sense: after all, being careful about things is a character disposition (a hexis), and the dispute is about whether we actually are in control of such character states. So Aristotle's answer thus far seems to merely beg the question. But he retorts:

-However, they are the causes of having come to be that sort of person, by living carelessly ( ζῶντες ἀνειμένως). And they were the causes of being unjust, by doing bad actions, and of being intemperate, by having spent their time drinking etc. For each sort of activity produces the corresponding sort [of character disposition]. And that is made evident by those who care ( τῶν μελετώντων) about any competition or practice ( πρᾶξιν); because they accomplish this by being active. So you have to be absolutely insensible to ignore that performing actions generates the corresponding states of character (? ξεις). (1114a3-10)

Aristotle goes on to expand on his conclusion by stating that, therefore, people who commit unjust acts are voluntarily unjust, and no one who acts badly can say that he is involuntarily unjust. So he takes it that by this point he has already won the argument. -But how? What was his winning argument?

To show that being virtuous or vicious is in our control, Aristotle adduces a crucial piece of evidence: the behaviour of athletes ("those who care about some competition or practice"). Which is rather surprising, if not disappointing. He seems to assume that merely watching someone train for a competition reveals how control over character works. But, really, what does an athlete working out have to do with the voluntariness of vice?

On closer inspection, however, maybe all we need to know about habit and agency is before our eyes when looking at a training athlete. To achieve her best performance, she knows she must practice, i.e. carefully repeat the same sort of action over and over and over until she generates the right cognitive and bodily dispositions. Because she knows the right dispositions are generated by repeating the right kinds of actions, she takes control of her habits by carefully repeating the kinds of actions that will turn her into who she wants to be. So the athlete's behaviour does reveal a secret of agentive control: we control our actions insofar as we carefully shape the habits that cause them. This is a variation on the theme found in the Problems passage discussed above: habituation is an exercise, a gumnastikon, through which we extend our naturally limited dispositions for receiving things and producing actions, thereby extending our control.

This dialectical passage is full of words related to care (ameleia,epimelethēnai, meletān, tōn meletōntōn), which highlights the main upshot: care for one's character is a necessary condition for having control over one's actions. Someone who ignores this (the dependency between actions and character states) would be "absolutely insensible", i.e. would lack all understanding of the human condition. And there could clearly be people who lack this self-understanding: Aristotle would not hesitate to deny it to natural slaves, probably to women, and perhaps even to the majority of people, who go about their lives guided by their passions and do not care at all about the fine (EN X.9 1179b31-1180a14). The problem for those who do not care for the shape of their habits is that they end up stuck with severely limited dispositions for sensation and action, that make them cling excessively to immediate pleasure and flee from even little amounts of pain. So they never develop the ability to control their actions in demanding situations: they will go for the small instant gratifications, and miss out on the hard-earned satisfactions of a fulfilled life. From this perspective, then, agency (i.e. the control over one's behaviour) does not belong to human beings qua such. Rather, it is an achievement that is attained by continuously elevating oneself beyond one's past dispositions through habituation.

Remember the paper's main question: Controlling our actions seems to imply controlling our goals; but how can human agents control their goals? Against traditional intellectualism, I have argued that we cannot establish goals directly by means of reasoning. Instead, character determines the goals we pursue, by establishing which objects appear pleasant and which appear painful. However, reason could determine the phantasia of the good indirectly, by directing habituation toward developing certain character dispositions. This is the first thesis of the position I earlier called 'indirect intellectualism', namely, that logos can determine our goals indirectly, by carefully shaping our habits. Clearly, care for habits is a task that only reason can perform: it requires considering actions instrumentally as means to build a certain disposition, specifying which actions would better embody that goal, and performing long-term coordination; so all of reason's functions are implied. That is one of the key reasons why anti-intellectualism does not sufficiently account for agentive control.

Having thus offered arguments against both traditional interpretations of Aristotle's theory of action (intellectualism and anti-intellectualism), and having developed the foundations of an intermediate position based on the nature of habituation as the gymnastics of the soul, it is time to offer some conclusions.

Conclusions

3.1. The circular structure of human agency

Let us look back at the big picture for a moment. In response to his anonymous opponent, Aristotle claims that we are in control of our actions insofar as we cause our appearance of the good, and we are responsible for our appearance of the good insofar as we cause our character. In the previous section I attempted to explain how habituation causes character and accounts for the moral and intellectual development required to achieve virtue.

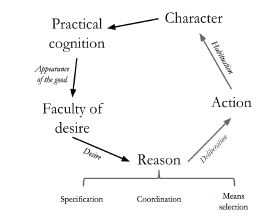

This enables us to understand how an agent can be the cause of her own character. A crucial part of the explanation turns out to be that human agency has a circular structure (see Fig. 1.3 [and contrast it with Fig. 1.2 above]): repeated actions generate dispositions of character; character in turn determines practical cognition (i.e. the phantasia of the good); practical cognition activates desires toward the objects that appear good; and desire-mediated by reason's specificatory, instrumental, and coordinating activities-shapes subsequent actions. These actions, in turn, generate dispositions of character. And so on.

This is a fundamental structural difference between human and animal agency, not previously analyzed in the interpretive literature. Animal action production is a linear causal process, whose starting point is the innate natural dispositions and whose end point is locomotion (cf. Fig. 1.1). In the case of non-human animals (and young children), nature innately specifies their objects of desire through their innate phantasia of the good. So animals are in control of their motions insofar as the principles of those motions are internal to them; but they have no control over the principles of their action, because their phantasia of the good is largely hard-wired into them by innate natural tendencies. The only way for an agent to take control of the principle of her action (i.e. the first mover, the object of desire, which sets all other movers in motion) is by making the whole system bite its tail, so that actions are able to modify their own originating principles. A human agent can do this (i.e. modify her phantasia of the good) if she can shape her habits. It thus becomes possible for us to act in order to acquire a certain character, thereby shaping the way the practical world appears to us.

Figure 1.3: The circular structure of human agency.

3.2. The two theses of indirect intellectualism

Given the analysis above, there are two main ways in which an individual's rational control over her actions is notoriously indirect. Here is the first one:

Indirect intellectualism 1: Reason determines the goals of action via careful shaping of character.

This thesis has the advantage that it can accommodate the key insights from both traditional intellectualism and anti-intellectualism: it preserves the division of labour (it is character, not reason, that directly determines our phantasia of the good), but it also explains how the soul's rational part can guide and rule over the non-rational part.

The functions of reason discussed above (specificatory, instrumental, and coordinating) are necessary for individual agents to shape their habituation patterns. Just as an athlete training for a competition must rationally select appropriate actions, and coordinate them toward doing well at the time of the competition, the autonomous individual agent must rationally select the specific practices, and coordinate them through time toward the acquisition of the character she wants to build for herself.

But how does she know what character she should build for herself in the first place? This is the terrain in which the anti-intellectualist is still right: the originary appearance of a certain character as good must necessarily precede all reasoning and deliberation about habit care. The first phantasia of the good is a consequence of the first steps of an individual's habituation. And importantly, such steps did not depend on her, but were performed by those other people who cared for her. So rational control over actions is indirect in another way:

Indirect intellectualism 2: The reason of other people allows for an individual to rationally control her own goals.

The social nature of individual agentive control is evident from these brief remarks: if we are in control of our actions because we are in control of our phantasia; and we are in control of our phantasia because we are in control of our habits. By transitivity, it follows that we are in control of our actions only insofar as we are in control of our habits. But more specifically, Aristotle claims that we are "in a way responsible" ( &πως αἴτιος) of our phantasia of the good and our habits (EN III.5 1114b2-3). This qualification is due, if nothing else, to the unavoidable fact that we must rely on other people for our initial habituation processes. So each individual agent's character is initially in other people's hands. How is this dependence on others compatible with individual autonomy and control? This is a large and complex topic, one that unites Aristotle's ethical and political theories, and that deserves a careful treatment. I will provide such treatment in an essay that follows the path that this one has opened up.

Footnotes

1. For their comments, which helped greatly improve this paper, I would like to thank Brad Inwood, Laura Liliana Gómez, Mark Kingwell, Klaus Corcilius, Ricardo Salles, Juan Piñeros, and the great audiences at the University of Toronto's Philosophy Department, the Ágora Research Workshop, the II Canadian Colloquium for Ancient Philosophy, and the II UNAM- Univalle conference. The responsibility is mine for the paper's remaining shortcomings.

2. See e.g. Pacherie (2008; 2011); Wu (2011; 2015); Shepherd (2014).

3. The word 'kurios' comes from the political context, meaning 'master' or 'lord'; Aristotle gives its significance an abstract turn as 'commander' or 'controller'. (See e.g. Eudemian Ethics [EE] II.6 1223a4--9.)

4. The canonical passages on animal agency are De Anima [DA] III.7--11 and De Motu Animalium [MA] 6-11. I offer a short sketch of this issue here, and discuss it further in my (Forthcoming).

5. The notion of 'phantasia' presents many interpretative complexities. I rely here on the widely shared view that one of its functions is allowing animals (humans included) to experience previously perceived objects while they are not perceptually present to them. Phantasia therefore entails some kind of perceptual memory, and some level of mental- modelling capacities that are useful, e.g., in imagining the attainment of a goal that is not yet achieved. (For more detailed discussion see Nussbaum (1978, essay 5), Frede (1992), Labarrière (1997), Moss (2012, Chapter 3), and Carbonell (2013).)

6. For some intellectualist accounts, see Irwin (1975); McDowell (1998); Grönroos (2015); Hämäläinen (2015). Intellectualism has been the dominant view in recent years, but Moss (2012) has made a strong case for anti-intellectualism.

7. I keep this, the negative part of the argument, at its bare minimum, to focus on the positive account. For more detailed criticism of the intellectualist and anti-intellectualist positions, see my (Forthcoming).

8. Such interpretation has been called 'Humean', since reason turns out to be little more than a 'slave of the passions', i.e. a mere assistant of non-rational goal-seting processes. This is a view not often supported, but often mentioned as a relevant dialectical opponent (cf. e.g. Irwin (1975); McDowell (1998a); Price (2011); Moss (2014)).

9. Classical versions of this view include Wiggins (1975), Irwin (1975), and McDowell (1998).

10. Price (2011, 152-153), following Broadie (1991). See also Morales (2003, 86--88).

11. ἔστι μέντοι ἡ προαίρεσις οὐ τούτου, ἀλλὰ τῶν τούτου ἕνεκα. ["Decision, however, is not of it {i.e. the goal}, but of the things that are for its sake."] (1227b38-39; cf. EN III.2 1111b26-29)

12. Cf. EN III.2 1112a13-17, III.3 1113a9-12.

13. More textual evidence for this view can be found in EN III.3 (1112b32--34) and EE II.10 (1226b10--12 & 1227a6--13).

14. The claim is repeated multiple times in EN II.3 and EE II.2-4.

15. E.g. HA (488b15, 588a28-31, 611a16, 612a3, 612b1); On the Parts of Animals [PA] (648a6-11, 650b19-20); On the Generation of Animals [GA] III.2 (753a11-14); EN (1141a26-28). How to precisely interpret Aristotle's attribution of notions like phronēsis and sunesis to animals, and the relation between these animal traits and their human counterparts, is a matter of discussion. On which see Lennox (1999, 16-ff.) and López Gómez (2009).

16. Animals who admit of a certain level of habituation include sheep (who can be habituated to act as leaders for their flock, taking them back to the barn at the shepherd's call [HA VI.19 573b25-27]); seals (who gradually habituate their young to spend time in the water [VI.12 567a6]); and deer (who lead their young toward safe places to habituate them to take refuge [VIII.5 611a19-21]). Some aspects of animal habituation are worth noting. First, animals can be habituated by humans or by themselves, as the examples indicate. Second, animals who partake in learning and teaching are "those which partake in hearing, not only those who perceive the differences between sounds, but also between their significations" (HA VIII.1 608a17-21). Their ability to grasp significations makes these animals able to be tamed by humans, and Aristotle thinks "tamed animals are better by nature than wild ones, and it is better for all of them to be ruled by a human; for that way they find their preservation" (Pol. I.5, 1254b10-13, cf. Prob. X.45 896a2-3). (This remark suggests that Aristotle did not spend much time in a circus or a factory farm, and that his animal-research practices probably were very humane.) For further discussion of animal rule by humans, and the differences between this and other types of rule, see Miller Jr. (2013).

17. On the former, see EE II.5 (1222a36-38); on the latter, see EN VI.13 (1144b1-17).

18. EN I.3 1095a2-10, I.4 1095b4-9.

19. The text provides no explicit identification, but there seems to be a consensus among scholars that this opponent is a Socratic who takes Socrates' no-one-does-wrong-willingly doctrine and derives from it that vice is not voluntary, although virtue and happiness are. (It has even been suggested that it represents Socrates himself (Boeri 2008, 10).) The opponent's claim, however, is expressed in a poetic style ( οὐδεῖς ἑκὼν πονηρὸς οὐδ’ ἄκων μακάριος (EN III.5 1113b14-15)) that resonates with the work of Epicharmus, an author who predates Socrates (cf. Gauthier & Jolif (1970, 213); Irwin (1999, 208); Broadie & Rowe (2002, 321)).

20. Some interpreters have claimed that this circular causal relationship between actions and character makes Aristotle's position paradoxical. (Take Morales (2003), who argues that since actions depend on character and character on actions, we are not in control of each particular action we perform, and therefore concludes---against the evidence mentioned above---that deliberation must be able to go against character-defined goals.) As I will argue below, Aristotle's position does seem to be circular, but in an virtuous way.

21. Aristotle's own reply appears in the middle of this phrase, interrupting the opponent's argument. I bracket it for a moment in order to present the opponent's argument in full.

22. The argument seems to rely on two uncontroversial implicit premises. IV can be inferred from III and the implicit Aristotelian thesis that people act pursuing what appears good to them (e.g. EN III.4). In turn, V can be inferred from IV and the Aristotelian claim that a person's character stems from the kinds of actions she repeatedly performs (e.g. EN II.1).

23. This naturalistic account of goodness appears elsewhere in Aristotle's texts. The (rather puzzling) EE VIII.2 is dedicated to examining the possibility that some people may turn out to aim correctly at the goal, and achieve it, out of pure luck. He argues that fortunate people (i.e. those who do well in life without ever really knowing what they are doing) cannot actually achieve the goal of life out of fortune [tuchē], because luck cannot produce the same result consistently. So fortunate people are successful not due to their good luck, but because of their good nature. The argument goes on to say that the cause of someone's good nature must be a sort of divine principle, which bypasses and surpasses reason, and even accounts for things like divination. Back in our passage, Aristotle seems to be dealing here with the radicalized version of the same naturalistic account of moral success. EN III.5 is much more critical of the naturalistic approach than EE VIII.2, however, perhaps because of an increased awareness that if we are not in control of our character we cannot be in control of our actions either. For if our phantasia of the good depends on our natural dispositions, how can we be in control of the actions it originates?

24. Compare this link between phantasia and character [hexis] with the memorable claim from EN III.4: "The excellent person discerns each thing correctly, and what is true in each situation appears [phainetai] to him. For the fine and pleasant things are proper to each character [hexis]" (1113a29-31).

25. Cooper thinks Aristotle, though not "careful enough to say so", does not conceive of habituation as "the purely mechanical thing it may at first glance seem"; what is not mechanical about it is that it "must involve also [...] the training of the mind", so that the trainee "comes gradually to understand what he is doing and why he is doing it", i.e. "to see the point of the moral policies which he is being trained to follow, and does not follow them blindly" (1975, 8). Burnyeat, for his part, holds that the difference between only having the that and also having the because consists in "a contrast between knowing or believing that something is so and understanding why it is so", and that the necessary starting points of practical reasoning are "correct ideas about what actions are noble and just" (1980, 71-72). In a similar vein, McDowell claims that "We travesty Aristotle's picture of habituation into virtue of character if we suppose the products of habituation are motivational propensities that are independent of conceptual thought, like a trained animal's behavioural dispositions. On the contrary, the topic of book 2 is surely initiation into a conceptual space [...] organized by the concepts of the noble and the disgraceful [...]. Possessing 'the that', those who have undergone this initiation are already beyond uncomprehending habit [...]. They have a conceptual attainment that, just as such, primes them for the reflection that would be required for the transition to 'the because'." (1998a, 39-40). Likewise, Frede holds that "habituation concerning the virtues of character [...] does not only consist in acquiring the disposition to be affected correctly in every particular situation, but also the disposition to choose the right action. And both involve a good deal of thought." (2013, 23)

26. Rhet. I.10 1369b16-18. See also EN II.3 (1104b8-13), VII.10 (1152a30-33), and Corcilius (2013, 141-142).

27. ἀνάγκη οὖν ἡδὺ εἶναι τό τε εἰς τὸ κατὰ φύσιν ἰέναι ὡς ἐπὶ τὸ πολύ, καὶ μάλιστα ὅτανἀπειληφότα ᾖ τὴν ἑαυτῶν φύσιν τὰ κατ’ αὐτὴν γιγνόμενα [.] (Rhet. I.11 1369b33-1370a5)

28. An animal moves by force (βίᾳ) whenever it moves or stays still against its own inner impulses, because of the influence of an external source of motion (EN III.1; EE II.7). We can imagine a hurricane lifting a cow and dragging her through the sky-whenever that happens, it happens by force-, or a cage impeding a bird's flight-its stillness occurs by force, against the animal's inner sources of motion.

29. "How come, then, nobody is pleased continuously? Is it because they get tired? For it is impossible for anything human to be continuously active. So there cannot be [continuous] pleasure either; for pleasure follows the activity." (EN X.4 1175a3-6)

References

Bermúdez, J. P. (s.f.). Aristotle's theory of agency: Against intellectualist (and anti-intellectualist) interpretations. (Preprint). [ Links ]

Boeri, M.D. (2008). Todo el mundo lleva a cabo lo que le parece bien. Sobre los trasfondos socráticos de la teoría aristotélica de la acción. Revista Philosophica, 33, 7-26. [ Links ]

Broadie, S. & Rowe, C. (2002). Aristotle: Nicomachean Ehics. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Broadie, S. (1991). Ethics with Aristotle. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Carbonell, C. (2013). Phantasía logistike en la configuración del deseo en Aristóteles. Ideas y Valores, 62 (152), 133-158. [ Links ]

Cooper, J. M. (1975). Reason and human good in Aristotle. London, UK: Hackett. [ Links ]

Corcilius, K. (2013). Aristotle's definition of non-rational pleasure and pain and desire. In, J. Miller (Ed.) Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics: A Critical Guide (pp. 117-143). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Curren, R. R. (2000). Aristotle on the necessity of public education. Lanham, USA: Rowman & Littlefield. [ Links ]

Frede, D. (1992). The cognitive role of phantasia in Aristotle. In, M.C. Nussbaum & A.O. Rorty (Ed). Essays on Aristotle's De Anima (pp. 279-298). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Frede, D. (2013). The political character of Aristotle's ethics. In, M. Deslauriers & P. Destrée (Eds.) The Cambridge Companion to Aristotle's Politics (pp. 14-37). Cambridge, USA: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Gauthier, E.A., & Jolif, J. Y. (1970). Aristote: L'Éthique à Nicomaque. Neuve, Belgium: Publications Universitaires de Louvain. [ Links ]

Grönroos, G. (2015). Wish, motivation and the human good in Aristotle. Phronesis, 60(1), 60-87. [ Links ]

Hämäläinen, H. (2015). Aristotle on the cognition of value. Journal of Ancient Philosophy, 9(1), 88-114. [ Links ]

Irwin, T.H. (1975). Aristotle on reason, desire, and virtue. The Journal of Philosophy, 72(17), 567-578. [ Links ]

Irwin, T.H. (1999). Aristotle: Nicomachean Ethics. London, UK: Hackett. [ Links ]

Labarrière, J.-l. (1997). Désir, phantasia et intellect dans le De anima, III, 9-11: Une réplique à Monique Canto-Sperber. Les Études philosophiques, 97-125. [ Links ]

Lennox, J. G. (1999). Aristotle on the biological roots of virtue. In, J. Maienschein & M. Ruse (Eds.) Biology and the Foundations of Ethics (pp. 405-38). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

López-Gómez, C. (2009). Inteligencia animal en Aristóteles. Discusiones Filosóficas, 10, 69-81. [ Links ]

McDowell, J. (1998). Some issues in Aristotle's moral psychology. In, Mind, value, and reality (pp. 23-49). Boston, USA: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Miller Jr., F. D. (2013). The rule of reason. In, M. Deslauriers & P. Destrée (Eds.) The Cambridge Companion to Aristotle's Politics (pp. 38-66). Cambridge, USA: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Morales, F. (2003). Libertad y deliberación en Aristóteles. Ideas y Valores, 121, 81-93. [ Links ]

Moss, J. (2012). Aristotle on the apparent good: Perception, phantasia, thought, and desire. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Moss, J. (2014). Was Aristotle a Humean?A partisan guide to the debate. In, R. Polansky (Ed.) The Cambridge Companion to Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics (pp. 221-241). Cambridge, USA: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Nussbaum, M. C. (1978). Aristotle's De Motu Animalium. Princeton, USA: Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

Pacherie, E. (2008). The phenomenology of action: A conceptual framework. Cognition, 107(1), 179-217. [ Links ]

Pacherie, E. (2011). Nonconceptual representations for action and the limits of intentional control. Social Psychology, 42(1), 67-73. [ Links ]

Price, A. W. (2011). Aristotle on the ends of deliberation. In, M. Pakaluk & G. Pearson (Eds.) Moral Psychology and Human Action in Aristotle (pp. 135-158). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Shepherd, J. (2015). Conscious control over action. Mind & Language, 30(3), 320-344. [ Links ]

Whiting, J. (2002). Locomotive soul: the parts of soul in Aristotle's scientific works. Oxford Studies in Ancient Philosophy, 22, 141-200. [ Links ]

Wiggins, D. (1975). Deliberation and practical reason. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 76, 29-51. [ Links ]

Wu, W. (2011). Confronting many-many problems: Attention and agentive control. Noûs, 45(1), 50-76. [ Links ]

Wu, W. (2015). Experts and deviants: The story of agentive control. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 93(1), 101-126. DOI: 10.1111/phpr.12170. [ Links ]

Praxis Filosófica cuenta con una licencia Creative Commons "reconocimiento, no comercial y sin obras derivadas 2.5 Colombia"