Introduction

In his work Was istGerechtigkeit (1975), Hans Kelsen briefly presents an argument against Aristotle's conception of justice. Kelsen argues that his definition is tautological and aims merely at justifying the social norms of his time. In this essay, I will attempt to show that Kelsen's criticism reflects a flawed understanding of Aristotle's philosophy. I will begin by briefly reconstructing Aristotle's conception of justice as a virtue. Then I will describe Kelsen's criticism to it. Having established the object of the controversy, I will offer one argument against Kelsen's criticism. Then I will summarise the discussion and my conclusions.

Aristotle's Theory of Justice

Justice is a part of Aristotle's ethical system, which is presented in his Nicomachean Ethics2. It is described as a moral virtue. In order, therefore, to reconstruct Aristotle's concept of justice, I will outline his concept of moral virtue, and then proceed to his conception of justice and its most important characteristics.

Moral virtue is, for Aristotle, "a habit or trained faculty of choice, the characteristic of which lies in moderation or observance of the mean relatively to the persons concerned, as determined by reason" (NE II 6 1106b 35-37 and 1107a 1-3).

By "habit or trained faculty", Aristotle means that moral virtue (or merely "virtue", for the purposes of this essay, unless otherwise noted) is neither a nature-given attribute nor a mere result of education. It is developed in man through the recurrent exercise of the action through which it manifests itself. Courage would then, e.g., be developed through acts of bravery. From that, two conclusions can follow: (i) mere virtuous acts do not make a man immediately virtuous, for virtuous acts can be accidentally (or by mistake, or without deliberation3) performed by vicious men; and (ii) moral virtue is voluntary, or at least impossible without the voluntary acts through which it is developed.

The fact that virtue is a mean (mesotes) is perhaps the most remarkable aspect of this moral system. Aristotle shows4 that, in any human moral characteristic that can possibly be good - some are bad in any amount, such as adultery -, either to exceed or to fall short of a given measure are bad and therefore vicious. Virtue is then the point that lies between the extremes of a given characteristic. The virtue of bravery provides a good example to that. If a man rushes to any challenge he faces without fear, he is an imprudent man. If he refuses them, even when facing them would be the honourable thing to do, he is cowardly. Facing the right challenges at the right time is the characteristic of a brave man. For that reason, bravery is the virtue lying between two vicious extremes: imprudence and cowardice.

As a final characteristic, the premises laid down in the Book I of the Ethics demand that this mean be determined by reason. Reason is, according to Aristotle, the function (ergon) of man, thus understood as its distinctive characteristic in respect to other beings in nature, and his happiness is only possible through the exercise of reason5. He uses that idea to arrive at the concept that the good use of reason is the end of human action, which provides the base of his moral philosophy. From that follows that, if virtue is good, then it must be in accordance to reason.

I can now proceed to describe the characteristics of justice, which is one of the virtues.

The word "justice" has two meanings in Greek. Justice in general means obedience to laws (NE V 3 1129b 11-13). It must be noted that Aristotle understands that the law prescribes the good of man and encourages him to be virtuous6. Justice in general sense is a virtue because it corresponds to the habit or trained faculty of abiding to laws. Unlike the mere sum of the other virtues, it has the special quality of being manifested towards others. That is, whereas the whole of the other virtues are defined with respect to the person who wields them, justice is only relevant in respect to other people, for, while all vicious acts are bad acts, only the unjust ones imply that the doer takes more than his share, thereby affecting others (if a man fails to be brave, he incurs in vice, but doesn’t hurt anyone simply by being a coward; the mere fact that a man in unjust, in the other hand, implies that someone is being hurt by him). But it nevertheless enfolds the whole of moral virtue. For that reason, justice has a twofold aspect: in this first meaning, it is coextensive with virtue, and therefore the just man is also virtuous or good7.

But there is also one meaning in which virtue is coextensive with gain, and it has to do with obtaining gain at the expense of others. This is the special sense of the word justice, which can be called special justice or justice as fairness. It is a part of justice in the general sense, belonging not to its aspect that is coextensive with goodness, but to the one that is coextensive with gain or loss. In this sense, a just act is fair, insofar as it does not result in the doer having more or less than what is his due. This kind of fairness is also a mean. It is situated between two extremes of injustice: on one side, taking too much of what is good or too little of what is bad; on the other, taking too little of what is good or too much of what is bad. This relation can be expressed in the form of a mathematical equality, because it always involves at least two subjects which are in some sense equal.

This equality can take two forms, firstly, it can take the form of an equality between fractions, such as A/C = B/D. That is, A relates to B in the same proportion as C relates to D. That can be called justice in distributions, because it expresses the distribution of a certain good or burden in relation to a certain merit or demerit. For instance, one could say that it is just to distribute honour in proportion to moral worth. Let us suppose, for example, that a certain amount of honour (H) is being distributed between two persons. Let A be the moral worth of the first person and B that of the second. The honour will then be justly distributed if the first person receives amount C and the second, amount D, such that A/C = B/D and C+D=H.

Justice can also be expressed in the form of an equality between certain amounts, in which case it applies to transactions. In Aristotle's terminology, the word "transactions" expresses ways in which individuals relate, either voluntarily (by means of a contract, for example) or involuntarily (for example by means of tort). If A and B be the amounts of a certain good possessed by two persons, the transaction will be just if the equality is preserved by the transaction, that is, A=B. If a carpenter exchanges a certain amount of chairs for a house with a builder, the total worth of the chairs must be equal to the worth of the house in order for the transaction to be fair. But a given amount of chairs can only be said to have the same worth as one house if they are measured in the same unity, because they are things of different kinds. Therefore, it is necessary, in order to assess the fairness of transactions, to come up with a way of measuring the worth of things different in nature. Money has precisely that function, that is, to bring all things to a common measure. In our example, then, if A be 10 chairs and B be a house, the transaction is only fair if, in terms of worth, A=B. If that equality is not true, for example because A>B, then, in order for justice to be restored, the transacting part who had the advantage must give the other part an amount of value equal to half the amount by which the transaction was unfair. If the chairs were worth only 80 coins but the house was worth 100, the builder must give the carpenter (100-80)/2=10 coins for the transaction to be fair.

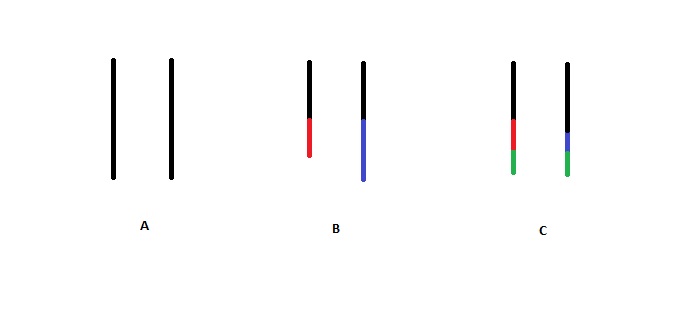

This can be expressed geometrically as well (Figure 1, below). The amount of good possessed by each part in the transaction may be represented as a black straight line. Both lines are initially equal (Figure 1. A.). If one line is longer than the other after the transaction, the transaction is unfair. In our example, we can assume that the transaction involved an exchange between the blue and red line segments, which are unequal, resulting in two different lines after the transaction (Figure 1. B.). It is the role of the judge in such situations to make the amounts equal again, dividing the straight line that became bigger and giving the excess to the smaller one (NE V 7 1132a 7-8)8. In our example, the judge must take half the difference between the blue and red lines, take it from the bigger line and attribute it to the smaller one. That difference is represented by the green lines.

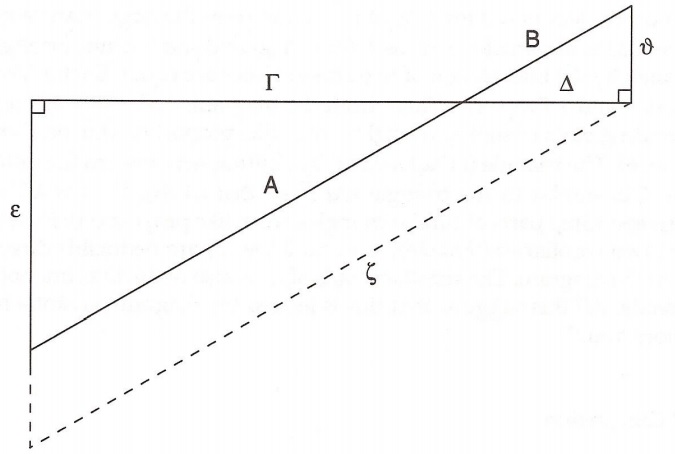

Justice in distributions can also be represented graphically, but that representation is much more complex. The simplest way of representing proportions is by means of similar triangles. In Keyser’s representation, below, one can assume, for example, that A represents the amount of social good awarded to a given individual, whereas ε represents his moral worth. If B is the amount of social good awarded to some other individual whose moral worth equals υ, the distribution will be fair, because, since the triangle AεΓ is similar to BυΔ, it follows that A/B = ε/υ (Figure 2).

Kelsen's Critique

Kelsen interprets Aristotle's ethical theory as an attempt at a scientific, "mathematical-geometric method" of determining what the virtues - such as justice - are (Kelsen, 1975, p. 34). According to this interpretation, therefore, Aristotle's work would only achieve its goal if it managed to develop an operational method for finding "justice" in concrete situations. Kelsen then proceeds to show that the theory is of no practical use, because it is tautological and presupposes its conclusions. He does that through two steps, attacking the general aspect of the theory and then the specific case of the virtue justice.

Kelsen begins by criticising the geometrical analogy employed by Aristotle to explain that virtues are means, explained above. The middle of a line segment, he argues, can only be determined when the points that define it are already known. That point corresponds to a given virtue, while the extremes are vices. This means that, in order for Aristotle's method to work, the vices must already be known. In the examples described in the Nichomachean Ethics, however, the vices are given by the "traditional morals of its time" (Kelsen, 1975, p. 35), which means that the virtues are actually determined by the morals and law of ancient Greece, and not a scientific method. If that is true, then the general aspect of Aristotle's theory fails.

Applied to the virtue of justice, this means that, in order to determine what justice is, Aristotle takes for granted what is unjust, because the just is the middle point between two extremes: the unjust that is done and the unjust that is suffered. In other words, if the unjust is taking too little of that which is bad or too much of that which is good, the just is the mean that lies between an unfair advantage and an unfair disadvantage. But that, according to Kelsen, is determined by the "positive morals and positive law" of the time (Kelsen, 1975, p. 36), since Aristotle's method is unable to determine it alone. That means that the so-called mesotes-formula cannot find what is just, but rather only justify and strengthen a given set of moral premises.

An Argument against Kelsen's Criticism

Kelsen's criticism can be divided in two parts. Firstly, he outlines his own interpretation of Aristotle's work. Then, he proceeds to point out the flaws in that work (as he interpreted it), attempting to show that (i) it is tautological and (ii) it can only reinforce a given moral system.

A short commentary on Kelsen’s probable intentions is due. The conclusion of his short book, not only regarding Aristotle but also Kant, Plato and Jesus, is that he cannot answer what Justice is - but neither can any of those authors. Therefore for him, as a scientist, a “relative” concept of justice must suffice: “his” concept of justice, instead of an all-encompassing, absolute concept (Kelsen, 1975, p. 43).

This seems to go along with his, rather paradigmatic, theory of Law, which rests on purity, understood as autonomy and separation regarding other fields of knowledge, including morals. It is therefore very convenient that justice is an empty concept, as it reinforces the need for a theory of law that exists in itself, without having to reach out to unfathomable ideas, such as justice. It seems, then, that proving Aristotle wrong would help Kelsen reinforce his theory of law.

I believe that Kelsen's argument is based on the straw man logical fallacy, i.e., he misinterprets Aristotle's work in order to attack it. Namely, I believe that he misunderstands the goals of Aristotle's theory, which he wrongly interprets to be the development of a scientific-mathematical method for finding just solutions to moral problems; then, he shows that this goal (which was never intended) is not attained; finally, he logically concludes that Aristotle fails. Therefore, although it has internal logical consistency, the criticism fails because it chooses the wrong premises.

There is no reason to presume that Aristotle ever intended to develop one such method. He does not claim to have done so in the Nicomachean Ethics, as Kelsen sustains. In Book V, Aristotle only stated he will "inquire about justice and injustice" in the same way he did with other virtues in the previous books. He also states that he will try to insert justice into the system he outlined before, finding how it can be a mean and what are its extremes. Before starting the examination of (moral) virtues, he also states that he intends to examine "what it is, and what its subject is, and how it deals with it" (NE III 9 1115a 4-6). None of that allows for the conclusion that the development of an operational method for the determination of virtue in concrete cases will be attempted.

Book IV provides another clue as to Aristotle's intentions when describing the individual virtues. When examining the virtue of truthfulness, he briefly stops to write that the study could be useful to (i) better understand the human character and (ii) show that the mesotes-formula applies to individual virtues (NE IV 13 1127a 13-18).

If, then, Aristotle makes no such claim as Kelsen attributes to him, one could ask if this intention can be derived from other aspects of the book. It is true that the whole of the Ethics is very practical in nature, to the point that a merely theoretical inquiry into the nature of justice would be unfitting of the work. It is specifically stated that the goal of the book is not a merely speculative or theoretical study; it should show man how to become good; otherwise, it would otherwise be useless (1103b). That would seem to go along the lines of Kelsen’s interpretation: if, after all, Aristotle wants to elaborate a useful theory, what good would it be if it can’t be used as a formula to find just solutions to actual problems?

But the same passage quoted above shows that a scientific method such as the one described by Kelsen not only is unintended, but also, according to Aristotle, impossible: for all inquiries in matter of practice must be "in outline only, not scientifically exact", especially in the study of specific cases (such as justice) (NE II 2 1104a 1-2). Kelsen’s interpretation is therefore not only far-fetched, but outright incoherent with the rest of Aristotle's Ethics.

That alone should suffice to show that Kelsen's criticism is unfounded, for, once his premise is showed to be false, his line of thought falls apart. However, it is worth further examining the matter. One aspect of Kelsen's argument still appears to be particularly convincing: that Aristotle's conception of justice is tautological. If that is so, that is, if his argument allows for no conclusions that cannot already be obtained from his premises, then it still fails in providing any insight into the nature of justice. I will, then, attempt to show that the definition is not tautological. That is, affirming that justice is a moral virtue situated between two extremes of injustice, which can present itself in two forms, justice in distributions and justice in transactions, brings new useful information to the field of moral philosophy.

Firstly, if justice is a moral virtue, then it follows that it is a habit or trained faculty, which is a very important point in itself. From that follows, for example, that even if one knows what is just (which depends on virtues of the intellectual, not moral, kind), one will not immediately and necessarily be able to act justly, for that requires the virtue of justice, and not merely a knowledge of what justice is. Although the point may not be of great importance for the philosophy of law (with which Kelsen was mostly concerned), it is a relevant conclusion about virtue theory and human character. To put it simply, Aristotle teaches us that being virtuous and knowing what virtues are are two very different things.

Secondly, the distinction between justice in distributions and justice in transactions identifies two distinct ways in which we can think about legal relations. Identifying which should be applied to what kind of human relationship has important consequences9. For example, most legal relations in civil law work on the basis of justice in transactions. That becomes most evident in contract and tort law. But even in those fields, distributive justice has an application. It is the case, for example, of the liability of the State for tort caused by its employees10. In such situations, when an agent of the state inflicts damage on a third person, the person is entitled to reparation against the State itself, not only the agent. This kind of solution cannot be justified by justice in transactions, and is better described by justice in distributions: a certain financial burden is allocated to the State (which lastly translates into the collective group of taxpaying citizens) to preserve the rights of an individual. That is justifiable because otherwise an action of the State (through one of its agents) would reduce the total amount of goods of one of its citizens, who, acting faultlessly, does nothing to deserve such harm. To remedy the situation, all of the society pays for the reparation, diminishing the total amount of good that would be distributed to them (or enlarging the total amount of harm, which takes the form of taxes), but preserving the individual proportions. This example should help illustrate just how much the categories outlined by Aristotle in his description of justice can be used to think legal relations11.

Further, in his description of specific virtues, Aristotle does reinforce what appears to be the traditional morals of his time. He exalts the bravery of the warrior who dies at war and the magnificence of the wealthy man who deploys his riches in tombs and temples for the gods. He even says things that seem abhorrent to us today, such that a master can’t be friends with his slave because slaves are mere tools, not unlike a shovel. Even his less absurd examples might seem naïve or outdated to the contemporary reader. However, it by no means disqualifies his ethical theory, although it might show that he applies it in a rather conservative way. Another moral philosopher might use the same framework laid down by him, particularly in Books I and II, and identify a different set of virtues, or modify the interpretation of specific virtues described by him. All of that could be done with the robust support given by concepts such as happiness as the good of man, moral virtue, the mean and the will, which provide excellent tools for that task. Moreover, he could hardly have acted differently. If he wanted to demonstrate that his theory works, he had to show that it could efficiently describe what his contemporaries perceived as moral virtue. If he had used the same premises and then gone on and applied them to values which were alien to Ancient Greeks - say, if he had used them to defend the Christian values of mercy or compassion - it would hardly have been convincing to his peers.

Another evidence of the usefulness and relevance of Aristotle’s theory is of empirical nature. In the millennia since the publishing of the Nicomachean Ethics, several important authors in moral philosophy in the West have in some way or another used his idea of justice, and especially the distinction between justice in distributions and justice in transactions. Izhak (2009, p. IX) gives an account of the impact of Aristotle’s distinction in the history of western moral philosophy:

True, for many centuries Aristotle's works on ethics have laid rather dormant, but their revival in medieval times constituted a major event in the Latin Christian world [...]. No wonder that Aristotle's analysis of the notion of justice as one of the cardinal virtues attracted the attention of the scholastics and provoked protracted discussions and controversies. A vast literature was the result.

A very important case of applications to which Aristotle’s theory led is that of John Rawls’ Theory of Justice, in which the idea of distributive justice appears most prominently (Rawls, 1999, pp. 9-10). Although the discussion presented in this essay is not the object of Rawls’ concerns, he does suggest a solution to the problem of the “usefulness” of Aristotle’s justice theory, by suggesting that “social institutions and the legitimate expectations to which they give rise” are the stuff from which we derive each person’s entitlements in a fair arrangement of social goods:

The more specific sense that Aristotle gives to justice, and from which the most familiar formulations derive, is that of refraining from pleonexia, that is, from gaining some advantage for oneself by seizing what belongs to another, his propriety, his reward, his office, and the like, or by denying a person that which is due to him, the fulfillment of a promise, the repayment of a debt, the showing of proper respect and so on. It is evident that this definition is framed to apply to actions, and persons are thought to be just insofar as they have, as one of the permanent elements of their character, a steady and effective desire to act justly. Aristotle’s definition clearly presupposes, however, an account of what properly belongs to a person and of what is due to him. Now such entitlements are, I believe, very often derived from social institutions and the legitimate expectations to which they give rise. There is no reason to think Aristotle would disagree with this, and certainly he has a conception of social justice to account for these claims. (Rawls, 1999, pp. 9-10; italics added by the author)

That shows that Aristotle's definition of justice is by no means tautological. It creates important distinctions to help us think concrete problems involving justice and fairness, and which can greatly influence the solution of moral (and juridical) problems.

But one criticism remains unanswered: the argument that the mesotes-formula itself does not help us determine what is fair seems to stand. It is indeed true that for the judge to find the centre of a line, its extremes must be previously given, and Aristotle says nothing to help us find them. If this argument is true, that might restore some merit to Kelsen's critique (with which Rawls seems to agree): Aristotle's theory would be by no means tautological or empty, but one of its points, which deserves several paragraphs of text, would appear to be destitute of usefulness.

I believe this problem can be solved. In the first place, Kelsen has omitted what Aristotle has to say about how one is to find the "mean" between the extremes. That is done through the "right reason", which is, in the case of justice (and action in general), the virtue of prudence, as explained in Book VI.

But even that seems to give no definite solution. Aristotle never wrote a formula that allows us to use prudence to find a just solution to a case. Kelsen might then argue that this solution is still tautological: it does no more than to say that one has to be prudent to be able to see what is just. But perhaps the problem lies in the fact that reading Aristotle's account of the mesotes-formula as a way to improve his theory of justice is exactly the opposite of its function in Book V. It might be rather that showing that justice is a mean is important for showing that it is a moral virtue, thus strengthening Aristotle's Ethics as a whole. It might be one more - although an exceptionally important one - among the many cases that confirm the hypothesis presented in Book II. Justice is indeed a form of mean, and "behaves" as a moral virtue. If that were not so, Aristotle would be forced to leave an important aspect of his Ethics out of one of its most important categories, namely that of the moral virtue.

Conclusion

In his attempt to disprove the applicability of Aristotle's of justice, Kelsen misreads the Nicomachean Ethics. He attributes to Aristotle the intention of creating an operational method for determining how virtues, including justice, manifest themselves. However, that intention is never stated in his work. On the contrary, at least one paragraph of the book gives strong evidence that Kelsen's reading is completely incoherent with Aristotle's moral philosophy. That alone is sufficient to show that Kelsen's thought is fallacious, but more is needed to answer his (rather powerful) argument that the theory has no practical consequence. To do that, we must show that his description of justice can - and does - influence the way in which we think about moral problems, and that is gives us a clearer idea of what justice is. I show, for example, that justice is a virtue - and therefore more than a simple behaviour or social construction - and that the distinction between justice in transactions and in distributions can mean the difference between receiving or not compensation for a tort caused by the State. Even if we acknowledge that, as Kelsen states, Aristotle reinforces the morals of his time, we must reject that he does "only" that, and that it would in any way speak against his theory. The strongest point in Kelsen's thought, however, is that the mesotes-formula nevertheless says little about what a fair solution in a given case is, which remains a problem even after we show that it is not meant to say anything about how justice should be applied. I formulate one hypothesis to solve that problem, by suggesting that the compatibility between the formula and the concept of justice is meant to reinforce Aristotle's theory of moral virtue, rather than his theory of justice.