Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Signo y Pensamiento

versão impressa ISSN 0120-4823

Signo pensam. v.31 n.60 Bogotá jan./jun. 2012

Reporting on Victims of Violence: Press Coverage of the Extrajudicial Killings in Colombia

Reportaje periodístico de víctimas de la violencia: cobertura de las ejecuciones extrajudiciales en Colombia

SANDRA MILENA RODRÍGUEZ *

* Sandra Milena Rodríguez. Colombiana. Realizó una Maestría en Medios de Comunicación y Desarrollo Internacional, en la Universidad de East Anglia en Norwich, Inglaterra. Se graduó en Psicología, en la Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, y realizó un diplomado en Cine y Medios de Comunicación en la Universidad de Bickbeck en Londres. Recientemente trabajó como investigadora de medios de comunicación para la organización International Broadcasting Trust en Londres, Inglaterra. Co-autora del reporte "Outside The Box" publicado en Inglaterra en Julio de 2011. Correo electrónico: s.milenal004@gmail.com

Recibido: Agosto 31 de 2011. Aceptado: Septiembre 9 de 2011.

Submission Date: August 31st, 2011. Acceptance Date: September 9th, 2011.

This research examines El Tiempo's coverage of the extrajudicial killings in Colombia and in a wider context the media coverage of violence. The literature found in this dissertation suggests that the way in which media report on victims of violence can either harm or help their healing process. The content analysis of one year coverage on the extrajudicial killings in Colombia shows that institutionalized voices, for instance official viewpoints are privileged sources of information; moreover the use of journalistic structures such as writing style and news values prevent the victims and their relative's testimonies to be heard and exposed to the society. Several challenges are posed when reporting on conflict and victims of violence, therefore media organizations and media workers are encouraged to critically reflect on their own practice in order to report on victims and trauma in a humane and transformative way.

Keywords: Media and conflict, Media coverage of victims and trauma, Content analysis of newspapers, Colombian media systems, humanistic story of victims.

Search Tags: Mass media and public opinion -Colombia - Newspaper reports -- Colombia - Violence -- Colombia -- Chronicles.

Esta investigación examina la cobertura periodística en el diario El Tiempo de las ejecuciones extrajudiciales, y en un contexto más amplio, el cubrimiento mediático de la violencia. La revisión teórica sugiere que la forma en que los medios de comunicación ejercen la reportería afecta la reparación de las víctimas. El análisis de contenido de los artículos producidos durante un año de cubrimiento mediático de las Ejecuciones Extrajudiciales en Colombia mostró que se privilegian los puntos de vista oficiales. De igual manera, en este artículo se cuestiona cómo estructuras periodísticas (el estilo de escritura, la longitud del artículo y los valores tradicionales de construcción de una nota periodística) pueden limitar la exposición de los testimonios de las víctimas. Se plantean desafíos con respecto a la relación entre medios de comunicación y víctimas de la violencia; debe fomentarse una reflexión crítica con el fin de ofrecer un cubrimiento humano y transformador.

Palabras clave: Medios de comunicación y conflicto, cobertura mediática de víctimas y trauma, análisis de contenido de periódicos, sistemas mediáticos colombianos, reportaje humanístico de víctimas.

Descriptores: Medios de comunicación de masas y opinión pública -- Colombia - Crónicas periodísticas -- Colombia - Violencia -- Colombia -- Crónicas.

Origen del artículo

El artículo es parte de la tesis de maestría en Medios de Comunicación y Desarrollo Internacional que desarrolló la autora en el tema de "Reportaje periodístico de víctimas de la violencia: Cobertura mediática del periódico El Tiempo de las ejecuciones Extrajudiciales en Colombia". Tesis de Maestría dirigida por Martín Scott, director de la facultad de Medios de comunicación y Desarrollo de la Universidad de East Anglia, en Norwich, Inglaterra.

Introduction

In order to describe the role that the mass media play in democratic societies Bonilla and Montoya (2008) elaborated the metaphor of the pendulum:

The pendulum swings from assisting civil society to exercise its right to freedom of expression and to fight for independence and visibility in the public sphere, to being an instrument of governance that is firmly in the hands of the political and economic establishment (Bonilla and Montoya, 2008 p.78).

According to theses authors it is the latter scenario that best characterizes the mass media momentum at the present. Although most countries in the world consider their political systems as democratic, conflicts continue to occur and entire communities around the globe struggle to gain public recognition and respect for their fundamental rights. Today's world faces huge social problematic such as poverty, oppression, marginalization, inequality, disease, famines, racism and displacement. These situations continue to trigger violence and internal armed conflicts.

Moreover, violence perpetrated by elites is the response that world's poor and marginalized meet when challenging injustice and oppression (Cottle, 2006). Within the previous context the media, as an essential part of society, are not only witness to this, but active mediators in it. Media's inevitable interaction with contemporary conflicts has resulted in a larger involvement of civilians, whether as spectators, victims or active participants in the conflict (Balanbanova, 2007).

Colombian's conflict is one of the examples that show the unimaginable levels of violence that a conflict can perpetrate on the civil society. This situation has inflicted a lot of anguish and suffering in the civil society and the number of victims of violence disturbingly increases day by day. Due to the present situation, the impetus for this research derived from the concerns about the increase in the number of extrajudicial killings in Colombia in the recent years. This study explores the Colombian press coverage on the extrajudicial killings, but especially by looking at how the press reported on the victims and their family members through a content analysis of one year coverage on the extrajudicial killings in the Colombian newspaper El Tiempo.

It is important to highlight that the media coverage on conflict has been widely studied; however the discussions about the role that the media play in conflict has hardly ever focus on the media relationship to the victims of violence. Therefore, the literature about the media coverage of victims of violence and its role in their healing process is reduced. This unexplored topic will be examined from an interdisciplinary perspective.

Literature Background

Colombian conflict context

Colombians armed conflict has been marked by the constant violation of fundamental rights by the guerrillas, the paramilitaries, criminal gangs and the state armed forces. Kidnappings, attacks on innocent people, landmines, recruitment of children, violence against ethnic minorities, displacement, selective assassinations, forced disappearances and extrajudicial executions are just some of the acts on a stage full of atrocities (Ospina, 2007). For over 50 years Colombians social fabric has been torn apart by a harmful conflict for those who have experienced the pain and suffering that it has left in its wake and invisible for others who want to deny its existence.

Moreover, Human Rights Watch report (20i0) indicates the emergence of new criminal groups all over the country, composed of formerly demobilized paramilitaries directly following the demobilization process. These successor groups have had great impact on the deterioration of the human rights situation in Colombia, especially because these groups have engaged in serious abuses against civil society where trade unionist, peasants and indigenous people have been the main victims. Information provided by the CCJ indicates that 4,261 people including 350 women and i8i children were killed between 2002 and 2008 by paramilitaries or the new formed paramilitary groups (UN, 2010).

However, the Colombian Foundation Security and Democracy (FSD) in the 2009 report about the balance of the situation of security in Colombia, based on statistics provided by the National Police, describes a decrease of 81% in violent actions perpetrated by the guerrillas and other newly formed criminal bands between 2002 and 2008. In addition, according to the Ministry of Defense statistics, during 2002 and 2008 the number of homicides was reduced by more than 45%. Restrepo and Spagat (2004) emphasized the sharp drop in both guerrilla and paramilitary attacks and the total killings rates under Alvaro Uribe's rule, being the lowest since 1988. However, while civilian killings have dropped, those of combatants are at the highest rate ever.

The figures and statistics about the Colombian conflict presented by official and non-official sources differ greatly. Leech (2008) considers that these discrepancies have led to a peoples perception of the conflict disconnected from the reality of the human rights situation on the ground. People are constantly exposed to news stories about killings perpetrated by the guerrillas while the abuses committed by the Colombian military and its paramilitary allies receive less attention. Therefore, people have been constructing a misconceived perception of the reality of the conflict. Two very different pictures of reality are being presented and whichever source has more credibility and whoever is winning -or not- this war it is a fact that Colombian civil society has been trapped and trampled in the middle of the conflict. Carrillo and Krucharz (2006), to this regards express:

"Colombians are experiencing a dramatic situation marked by political violence, massive forced displacement, the implication of the Colombian armed forces in crime, the paramilitarization of the country and a state of impunity protected by the highest political institutions" (p. 43).

The press in Colombia

Within this context it is important to look at the media system in Colombia and some of the important aspects on the relationship between media and conflict as it is censorship and news sources. Colombian's political and cultural history has permeated the journalistic and informative tradition of the country, a history marked by political upheaval and weak state institutions (Bonilla and Montoya, 2008). A limited two party political system and a family run ownership model have characterized the media systems in Colombia. According to Rey (1998) the liberal and conservative parties were especially linked to Colombian press.

Colombian press has been part of the ideological expressions of the political power, a site where political leaders have relied to express their ideologies. In fact, most head of the State over the last 50 years have practiced journalism at some point in their lives. Indeed, they are usually shareholders in many of the media companies. As an example the actual president of Colombia, until recently was a shareholder of El Tiempo. Martín-Barbero argues that "Colombian press is heir to the deeply doctrinal, militant and partisan journalistic model" (p.80 Bonilla and Montoya, 2008). For instance, between 1880 and 1980, 167 newspapers were founded in Colombia, now days only 35 exist. What is more, in a globalized market driven economy during the first decade of the 21st century many Colombian media outlets have open up to the market; this has result in the acquisition by major international groups of Colombian's most important media companies (Forero, Arango, Llana, Serrano, 2010). For instance Spanish investment in Colombia has strongly grow in the recent years, with more than 120 corporations, having an impact on almost every sector of the economy, especially the banking and telecommunications sector (Forero, Arango, Llana, Serrano, 2010).

The traditional concentration of media ownership in hands of elite families and the close relationship between political parties and press in Colombia, has limited the journalistic autonomy that should differentiated the media organization from other institutions, with distinctive set of personal values and practices (Hallin, 2008). Indeed, these family-run businesses rarely allow a separation between ownership and editorial control (Hughes and Lawson, 2005). Hallin (2008) highlights that there has been a tendency to the political instrumentalization of the media, and this has limited the development of a professional journalism independent from the political interest. What is more, due to the ongoing armed conflict, Colombia media has also been subjected to attacks coming from criminal groups that through threats, kidnappings and killings attempt to affect media content. This situation has lead to what is call self-censorship:

"fearing for their safety journalist often refrain from publishing stories counter to the interest of paramilitary groups, guerrilla and drug traffickers" (p.93, Caballero).

In this context, Hughes and Lawson (2005) describe that perhaps one of the most important barriers in Latin America media is the weakness in the rule of law, which results in the aggression against the media by both state and nonstate actors. Caballero (2000) points out that Colombian media has gone through a hard struggle in order to tell the stories of Colombians's distress and suffering:

"Colombian's besieged press cut cross the country because the flow of information has been manipulated, slow down or even violently stopped" (p.90 Caballero, 2000).

In addition, journalists are caught in the cross fire being at risk because of intimidation and threats to their lives. Caballero (2000) recognized that the lack of organizations that protects journalists and promote professional solidarity is one of the major problematics that media workers and media organizations especially independent media outlets have to face. In addition, the state's inaction and inefficacy has lead to absolute impunity in cases of violence against journalists. Therefore, reporting on Colombian conflict, from an independent and critical position could be seen as a dangerous job. For example, reporting on the Extrajudicial Killings can be seen by journalist as a sensitive issue where media organizations and workers could response by not reporting due to self-censorship, however, death treats and direct censorship is still common practice. According to Reporters without Frontiers, although the number of journalist murder has fallen since 2002, many journalists have been forced to flee the country due to Paramilitary treats.

International examples of Media censorship

In an international context, as well as in the Colombian case, states have always preoccupied about the role of the media in conflict, especially for the disclosure of information consider inappropriate for the public light. (Halliday, 1999). However, during armed conflicts censorship seems to be inevitable, either coming from the State or/and as in the Colombian example, from the actors involved in the conflict. Schlesinger (1991) highlights that in democratic societies censorship threatens the legitimacy of press freedom. However, when decisions need to be taken about security matters, the media line is drawn "as near as the core of security issues" (139). Furthermore, Graber (2003) recalls that strict censorship legislation used to be imposed by governments on the media before the Second World War. Nevertheless, this relationship changed and mutual cooperation, especially between press and government, has been a common practice pattern in different parts of the world. (Galliner, 1980, by Schlesinger).

An explicit example of the State's intentions to control the flow of information is the media coverage of the Gulf War. Journalists were exposed to major restrictions in the access to information. Consequently, military members were the only source of information that journalist had, briefing the press in all aspects of the war (Graber, 2003). Another important example of media censorship is the media coverage on Northern Ireland's paramilitary conflict. Gilbert (1992) describes that the United Kingdom's Home secretary in 1988 banned the broadcasting of any pronunciation made by any representative or supporter of the paramilitary organizations, including the ban of media coverage of the political party Sinn Fein. According to Cook (2003), the Northern Ireland case offers a field of study about an important journalistic responsibility that lies upon journalist: the decision making on behalf of the society of "who gets to speak, when they speak, and how the messenger or message is framed" (p89).

Media news Sources

An important way through which governments and official discourses make their way to the public sphere is through the already privilege position they hold as news sources. Western media has traditionally relied on known, credible and official sources; sources consider authoritative. Therefore, institutionalized voices have always had an easier access to the media (Dijk, 1988). To this regards, Keeble (1994) argues that the kind of sources used routinely by journalist reflect the unequal distribution of power in society. Moreover, Schlensinger (1994) mentions that the possibility of being considered an authoritative news source is limited to certain groups that already enjoy of a strategic social position. The privilege of being publicly heard given to particular groups in society allows them to establish the initial interpretation of the topic. In this context, counter or different perspectives are placed in disadvantage:

"some claim makers start with a real advantage over others by virtue of their insider status, their position in the government or burocracy" (Jenkins, 2003 p.139).

Therefore, the study of news sources can provide relevant clues about the ideologies and discourses that sustain unfair and unequal power relations; McQuail (2003) highlights that news sources play an important role to ensure that political and economic hierarchies remain untouched. Accordingly, Cohen (200i) describes the possibility of being an authoritative news source in terms of "The hierarchy of credibility", defined as:

"the unequal moral distribution of the right to be believed determines which voice is heard" (Cohen, 2001 p.175).

Therefore, politicians, military members, academics, doctors between others; are some of the people who intrinsically enjoy of this authoritative moral status, being given the possibility to express their opinion to the wider society.

For instance, Leech (2008) analyses, in the daily press coverage of Colombian conflict that whenever killings of civilians happen the mainstream media, relying on official sources, dutifully attributes the responsibility of the killing to one of the illegal groups, usually the FARC, accusations made without investigating themselves. In the case of the Extrajudicial Killings, it hast turned out into a great concern how this kind of reporting is affecting people's perception of the conflict, a perception disconnected from the reality of the human rights situation on the ground (Leech, 2008).

People are exposed constantly to news stories about killings perpetrated by the guerrillas while the abuses committed by the Colombian military and its paramilitary allies receive less attention. For example, in a study developed in 2007 about the New York Times coverage of Colombian conflict; according to this Newspaper the guerrillas were responsible for 80 percent of the killings of civilians. Meanwhile, the paramilitaries were responsible for only the ten percent and the military for the five percent. However, when compared to a study by the Colombian Commission of Jurists (CCJ), during that year the guerrillas were responsible for 25 percent of the killings of civilians; the paramilitaries were responsible for the 61 percent and the Colombian military for the remaining 14 percent (Leech, 2008).

In this order, Kothari, (2010) highlights that absolutely lie or biased perceptions can be communicated by sources which reporters or audiences might not always be able to distinguish. Therefore, the analysis of news sources and censorship suggest that the argument of believing that reporting operates in an objective and balanced way needs to be questioned. Moreover, it is important to start thinking how alternative discourses might be able to permeate official discourses (Spencer, 2005). Throughout the ideological discourse that surrounds the complex media and conflict relationship; the victims of violence appear to have been almost completely forgotten. The victims of violence are crucial actors caught in the middle of this relationship, but so far the ones given the less attention. An important question arises; are the victims important within the discourse of media coverage of conflict and violence at all ? Or, simply "unimportant, isolated people in remote parts of the world" (Cohen, 2001 p.12).

Reporting on Victims and Trauma

The number of victims of violence increases day by day and year by year in Colombia. The psychological distress that the conflict leaves in its wake has marked the lives of thousands of people, generating different psychological responses. Therefore, after examining important aspects of the media and conflict relationship especially in the Colombian context and highlighting that within that discussion the victims of violence have been mainly ignored; this chapter aims to constructively understand how the victims' and family members of the victims are being affected after experiencing violence and how not only the individual identity but the collective identity and the society as a whole is being damaged. This chapter will also look at the importance of narrative, expressed through the stories that journalists write, in the healing process of the victims of violence and in the re-construction of the collective memory.

In order to understand the nature of the psychological impact inflicted on victims and/or victims' relatives of political violence, it is important to briefly explain the perspective from which trauma and psychological distress is going to be understood. Traditionally, in the Western world the understating of trauma and psychological anguish has been grounded in a medical tradition.

The individual has therefore been defined as an autonomous being whose construction has been the result of an isolated process (Braken, 1995). This individualistic perspective of the human being undervalues cultural, social, political, economic and historical aspects, essential in one's identity construction.

From the Western perspective, when political violence occurs, psychological trauma is treated at the individual level and understood as an individual problem. On the other hand, a Latin American perspective based on the psychology of liberation proposed by Martin-Baro (2003) understands suffering and traumatisation, due to political violence, as the result of socio-political circumstances that have transformed into psychological distress. Martin-Baro (2003) suggests that is needed to reconceptualise the meaning of trauma as a psychosocial process expressed in the:

"concrete crystallization in individuals of aberrant and dehumanizing social relations, such as those prevalent in the situation of civil war" (Lykes, & Brabeck, 1993 p.528).

The latter angle of psychological trauma does not ignore the influence of personality structures in traumatic situations (Munczek & Tuber, 1998). However, it recognizes that when political violence and repression take place, the meaning of the event can not be disconnected from the cultural, social and political context (Bracken, 1995). Munczek & Tuber, 1998 points out that political repression impacts not only on the whole society, but in a greater way those directly involved. People directly affected or the family members of whom have been affected by political violence, Munczek & Tuber (1998) explains, experience a double source of anguish. On the one hand, there is the painful experience lived for the loss of the loved one, and on the other hand, the social denial of the event and the social discrimination and isolation imposed on affected individuals and families (Neuman, 1990) The loss of a loved one induces strong feelings of pain, confusion and disbelief, a situation which makes the grieving process that much more difficult to face.

Particularly important in the context of war and violence is to focus the attention on the victims of violence and their healing process. Indeed, Staub (2006) highlights that unresolved psychological wounds resulted from violence and fear, mistrust or hate disrupts the process of rebuilding interpersonal relations and can lead to renewed violence. Moreover, Munczek & Tuber (1998) posits, that in Latin America the process of mourning a disappeared or murdered family member is exacerbated by the families' fear of continued persecution. The victims and families of the victims of violence, according to Staub (2006), are identified as enemies of an ideology that the perpetrators have created. Therefore, the feelings of security and control over their own life, their positive connection to other people and communities and their positive perception of their identity and the world are deeply damaged. The survivors and victims of human right violations feel vulnerable and unable to trust. This creates an environment where the other is seen as dangerous and as a possible threat to life (Staub 2006).

Identity

Identity, according to Daniel (2009) is constructed by multiple spheres that interplay in the dynamic process of construction. Among these spheres at interplay are the biological, interpersonal, cultural, political, social, familial, communal, ethical, religious and spiritual. These different layers interact dialectically in a process pierced by a wide range of social relations. In a stable situation an individual should be able have free psychological access and movement within these dimensions. When political violence occurs many of the individual and social dimensions parts are afflicted (Danieli, 2009). For instance, victims and their family members, instead of receiving recognition and support, are subjected to isolation, they may have to flee for safety, may not be able to hold a funeral or even lose their job, facing severe economic and social difficulties; "these losses occur in the context of, and/or provoke, other losses and stresses" (Munczek & Tuber, 1998).

Therefore, feelings of rage, impotence, injustice, governments' lack of accountability for the actions and in the case of forcible disappearance of a loved one the fact of not being able to know exactly what has happened, where, how and why, according to Spiegel (1988), generates in the family members a sense of spatial and temporal fragmentation and the powerlessness to carry on emotionally with their lives. (Becker, at. 1990) working with victims of political repression in Chile, conclude that:

"it is necessary to heal the socio-political context for full healing of individuals and their families, just as it is necessary to heal individuals to heal the sociopolitical context"(Danieli, 2009 p. 351)

Staub (2006) mentions that psychological change is not only brought about by the individual, institutions and how they operate become relevant in maintaining or subverting these psychological changes;

"whether the media devalues or humanizes groups, how the justice system or schools operate, the nature of leadership, and structural justice or the situation of groups in society are crucial in promoting or hindering reconciliation" (869 Staub, 2006).

The individual recovery of the person is mainly bound up in the recovery of the wider community; thus "Intrinsically the recovery overtime is linked to the reconstruction of social and economic networks, cultural institutions and respect for human rights" (Bracken, 1995 p.1081).

Personal Testimonies

Silence has proven to be detrimental to the victims and family members of victims of political violence; it obstructs the socio-cultural reintegration and deepens the sense of isolation, loneliness and mistrust in society (Danieli, 2009). Staub (2002) after listening to the testimonies of the victims of the holocaust mentions that, survivors of such trauma "did not only need to survive in order to tell their story; they also needed to tell their story in order to survive"(68). In spite of this, in the context of political violence, silence could be the only option in order to survive. Indeed, the official response to political violence is usually silence and lies (Munczek & Tuber 1998). Verdoolaege (2005), analyses the importance of testimony and telling one's story as a way of resisting silence and inducing psychological healing. Testimony, however, contributes not only to the individual recovery, but also to a process of social recovery. Cottle (2006) points out that when memories of past experiences of violence and injustice are mediatized to a wider audience, this can assist in the process of acknowledging the pain and suffering of others and contribute symbolically to a process of recognition of the collective damage inflicted by violence. Therefore, personal testimonies publically heard, can be a powerful communicative form that enhance media capacity "to bear witness and communicate the conflicts and injustices perpetuated within a globalizing world" (Cottle, 2006 p. 182).

Writing about Victims of trauma

In the previous section the importance of story telling and narrative in the healing process of victims of violence and in the construction of the collective identity as highlighted. This section aims to explore how the mass media, through the writing process of news stories, can positively affect the victims as well as the collective identity. First and foremost, it is important to recognize that journalism belongs to the area of human expression, of expressive activity; news writing is fundamentally storytelling (Roeh, 1989). Bell (1998) to this respect adds "Journalists do not write articles, they write stories with structure, order, viewpoint and values" (p.64). Therefore, the daily happenings of our societies are conveyed in stories presented in the media (Bell 1998).

Several aspects are at interplay in the process of constructing a news story: Bell (1998) highlights that the final form of the story is affected by a selection and editing process applied by the journalist and the editor. Stories about real events are constructions of meaning and they look to establish meaningful closure (Roeh, 1989). Indeed, the assembling of meaning is not a static process that ends with the final form of the news story, this is an ongoing process that continues to be built once the story is reached by the audience, Lifton (2009) notes "we are meaning hungry creatures and we must create meaning every moment of our lives" (p.70).

Although the complete meaning constructed by the audience when reading a news story is unpredictable because "there will be always something about the question of the audience that will remain unanswerable" (tester, 1994 p.81) a vast responsibility lies upon the journalist when writing news stories about victims of violence. This is a story that involves the pain and suffering of others and journalists play an important role as the "mediators between those immediate survivors who experience the war or the event viscerally and the more distant survivors -the rest of us on the home front" (Lifton, 2009 p.69). Besides that, the journalist has the privilege to reach the story in an advantageous double temporal position; they are allowed to interpret the event at the time that it occurs as well as at the time of retelling the story (Zelizer, 1993).

Cote and Simpson (2000) propose a humane reporting perspective when covering violence and reporting about the victims of violence. This perspective emphasizes the conviction that news can tie up the victim and the public in a constructive relationship, through the rigor of thoughtful reporting practices (Cote and Simpson, 2000). These authors highlight the importance of remembering that a victim's story is not simply a news story, but a true portrayal about real human beings, their suffering and pain. Journalists can act humanely towards victims while acting in accordance with journalistic values. Furthermore, understanding the basics of how violent acts affect people's lives could help journalist to get close to the pain of others, then unimaginable situations begin to take form and then can be translated into narratives (Lifton, 2009); journalists "do best when we reach deeply into the pain from which to make that narrative" (Cote and Simpson, 2000 p.71).

In accordance to this perspective, a humane treatment of those in the story recognizes that in the relationship to victims, the interviews, the articles, the photographs all have the possibility to harm or help in the recovery process of the person victim of violence (Cote & Simpson, 2000). Moreover, "if the story is told at the rights time in the right way, it can be a catharsis that releases some pain and gives their lives new dignity" (Cote and Simpson, 2000).

There exist several journalistic genres and formats that journalists have at hand when writing news story, "once we accept that news, like narratives elsewhere is a way of giving form to experience, we can not ignore the 'power-of -the genre' theory (Roeh,1982 p. 166). Lifton (2009) notes that the interview decreases the banality and the possible ideological constraints imposed by the journalist's own writing, that is, the interview as a communicative form gets to the direct human experience. On the other hand, Zandberg (2010) mentions that, normative structures, news values and especially the routinely use of language, for example by newspapers, can weaken the intensity of the events, a situation that could lead to the trivi-alization of the event. An important effort must be put towards the development journalistic techniques that personalize the narratives given by the victims and therefore, contribute to their healing process and the reconstruction of the collective identity.

Collective identity

Throughout this chapter the importance of narrative in the process of construction of news stories about the trauma and pain of others has been emphasized. Writing about violence and trauma involves a dialectic interaction where the final story will not only have an impact on society but also on the victim of violence. Equally, the victim is affecting the news story and therefore society. According to Zandberg (2010) the collective memory is constructed through narratives organized in stories about the past and the present. This suggests that to writers of stories has been entrusted the responsibility to shape societies' collective memory. What is more, societies' collective memory is being daily formed through the stories being written in the newspaper. Newspapers have become a platform for social and cultural struggle and as storyteller of the daily happenings. Therefore, journalists as storytellers and writers have been granted the authority to influence the collective memory (Roeh, 1989).

Media research acknowledges that the process of constructing the Collective memory is similar to that of journalistic practice. Accordingly, the Journalist selects events and facts and constructs them into cultural and historical frames. Halbwachs (1992), recognized that the collective identity constantly relates to collective memories and it is through these memories that the community recognizes itself. These are usually memories of a common past, of events that have been commemorated, interpreted and reinterpreted, different stories about the social, political and cultural context compete for a place in history (Zandberg, 2010). Far from being a static process, the collective identity is constituted in action and continually reconstituting itself in line with the political context (Schlesinger, 1991).

Societies that have experienced repressive political regimes such as Argentina, Chile and Uruguay, where the core base of the collective life was deeply affected, Roniger and Sznajder (1999), detailed that basic social expressions such as participation, mobilization and organization were deeply damaged. The regime:

"curtailed individual rights and suppressed opinions for the sake of the common good as defined by the military rulers; they imposed a truth which citizens could not challenge and for which no accountability could be demanded, a truth that eventually and to different extents proved to be tainted by lies, especially in the area of human rights" (Roniger and Sznajder, 1999 p.224).

Therefore, in situations of political violence and in the process of the collectives identity's construction, relevant questions such as "what we as members of collectivities socially forget and what we remember and why (Schlesinger, 1991 p.181) should be asked. Furthermore, it is relevant to ask how the media contribute in assembling meaning to the collective memories, what is remembered, what is forgotten and why. In the Colombian case, with regards of the story being told about the extrajudicial killings, what kind of collective identity is attempted to be built, one that legitimize violence or one that protects and respect the human rights.

Research Design and Methodology

A complex content analysis of news articles about the extrajudicial killings was developed. The idea was to explore the way in which the newspapers reported on the extrajudicial killings and special attention was paid to how victims and family members of the victims were portrayed. The topic of extrajudicial killing is complex to analyze, and not many previous, if any, content analyses on this topic have been done before. Therefore, defining the categories of analyses was a time-consuming process; especially difficult was to decide the elements of the article to be counted and what possible information could be inferred from them. A total of seven (appendix II) categories were used to analyze the 90 articles, therefore the coding process was also time-consuming.

Firstly, in order to identify the news sources of information in the news articles was counted the persons voice and the institution mentioned in the article. Secondly, in order to identify specific journalistic characteristics of reporting on the extrajudicial killings, the writing style, length and tone of the articles were analyzed. And finally, in order to explore how the victims were represented was counted if the occupation of the victim was mentioned, and that of the perpetrator and the theme of the article.

Content Analysis

There exist different analytical tools in order to investigate media texts and make claims about media content. Firstly, it is relevant to mention that content analysis is a quantitative method that requires the quantification of content elements (Berelson, 1971). Fiske (1990) mentions that the quantification of elements in the media text is designed to produce objective and measurable characteristics of the manifest media content. So that, as Carney (1972) explains, once the elements are identified and quantified, it is possible to visualize how the parts of the media text relate and contribute to an overall structure, and once the information is gathered together, then "you can seen what is not there" (Carney, 1972 p.17). Therefore, Content analysis is considered a transparent and flexible method; it can be applied to a variety of information, allows to track changes in time and the coding shame and sampling procedure can be easily use in follow up studies (Bry-man, 2004). Moreover, is a technique that allows making interference, through objectively and systematically identifying specified characteristics of the message (Carney, 1972). It can also reveal, across a large number of cases, a repetitive process of representation that is affecting audiences' values and believes (Bryman, 2004).

When aiming to make claims about latent rather than manifest content, content analysis can be particularly problematic Bryman (2004). Nevertheless, Bryman (2004) notes that sometimes content analysis can shed light on questions by conducting additional data collection. In order to obtain an objective and reliable analysis of the media content, the analyst's subjectivity must be minimized Berelson (1971). Moreover, regardless of who is analyzing the data when applying the categories to the same content the results should be the same Berelson (1971). Therefore, Carney (1972) affirms that the quantification process rigourosity while the questions' strength will determine if the content analysis is well founded. Therefore, a careful definition of the categories of analysis is an important aspect to take into account due to the fact that this will affect the validity of the content anlaysis. If the definitions are clear and largely agreed then the validity is higher Berelson (1971).

Sample

This research examined the number of articles about the extrajudicial killings and the missing Soacha case published during one year, from September 2008 to August 2009, in the online version of the Colombian National newspaper, El Tiempo. El Tiempo is the newspaper with higher circulation in the country reaching around 1,265, 0000 people. Therefore, it was selected for this study. The articles were searched under the section of Nation and two different wordings were used in order to search for the articles online:

- Extrajudicial Killings (Ejecuciones Extrajudi-cales) and

- Soacha missing (desaparecidos Soacha). The two wording selection was chosen because in September 2008, 11 missing youths from Soacha appeared in the media. An interesting finding while searching for the articles was that when using the word "Extrajudicial Killings", almost no articles relating to the Soacha case were found. Therefore, a second wording selection was used "Soacha missing", which found articles relating to the case of the missing youths. The articles found were combined, making sure that none of them were repeated. In order to have a representative sample that could show trends over time and to reduce the sample size, the articles selected were one week coverage on each of the twelve months, starting from week 1 of September 2008, moving onto week 2 of October and so forth, through each month until August 2009. In total, 90 articles were analyzed.

Coding Manual

A coding manual was designed (see appendix I) that included the categories (see appendix II) for each dimension being code. The coding manual was tested by two different people in order to assure consistency and reliability. They were given the coding manual and an article to code, and then it was expected that they produce the same results when applying the categories to the same content. The persons made some comments with regards to the theme of the article and the action describe against the perpetrator. Then their comments were taken into account and incorporated in the coding manual. However, overall, the coding manual was seen as clear and logical.

Findings and Discussion

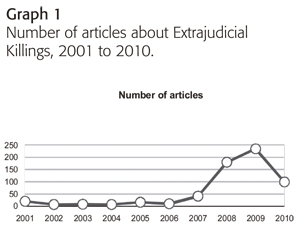

Graph 1. Shows the number of Articles about the extrajudicial Killings from 2001 to 2010. There is a minimal steady trend in the number of articles in 2001 to 2007. However, in 2008 the number of articles dramatically increased reaching a peak in 2009. Coincidently, the case of the Soacha missing youths came to the public light in 2008. Extrajudicial killings have been an ongoing problematic since 2002. However, according to the CCEEU report, 2006 and 2007 saw the largest number of reported extrajudicial killings; El Tiempo, did not begin to report more on this situation until 2008.

It could be argued that the irrepressible explosion of the Soacha case forced its way to gain unprecedented media attention. Nevertheless, different factors could be influencing the underreporting on the Extrajudicial Killing. Firstly, a lack of journalistic investigative framework to approach this topic, that could have followed up the cases of Extrajudicial Killings; Secondly, the reliance on mainly official sources about the conflict who are manipulating the information; Thirdly, self-censorship or censorship coming from a one of the actors involve in the Extrajudicial Killings; Fourthly, newspaper's ownership and political relations could be influencing too. Probably, many more reasons could be taken into account, nonetheless, whatever the reason reasons are, there is a sign of underreporting on this major human right violation, that in the end is greatly affecting the civil society's perception of the conflict; moreover, this shows how the victims and family members' of the victims have been subjected to no recognition at all in the media.

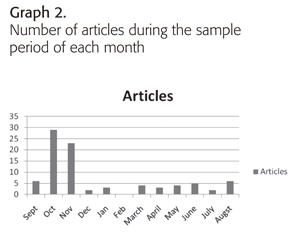

Graph 2. Shows the number of articles that appeared during the sample period. The largest numbers of articles were published during the months of October and November 2008, with 29 and 23 articles respectively. In December the number of articles decreased significantly, and in February it dips to zero before steadily beginning to increase, although relatively fewer in volume than during the previous autumn. Interestingly, chapter one mentioned that after the explosion of the Soacha case, more complaints from different parts of the country began to reach the Colombian justice system with people denouncing the disappearance of their loved ones in similar circumstances. However, the newspaper's coverage of this phenomenon does not seem to reflect that trend. It could be said that the newspaper's attention and coverage on the extrajudicial killings exploded suddenly in September, receiving significant coverage for two months, before attention dramatically reduced over the following months. Apparently, the extrajudicial killings lost their importance as news, a decline possibly related to news production values where an event that features heavily in the news reaches saturation point and loses its news value. To this regards, Bignell (2002) considers that news is a narrative constructed by making use of specific criteria of news value where a selection process has taken place in order to determine what news reports are given greatest significant. This tendency has lead to a forgetting of the importance and responsibility of journalism (Bignell, 2002). Furthermore, it could be argued that El Tiempo's short attention span in reporting on this situation is affecting the possibility of keeping the public interest in the mind of the audience.

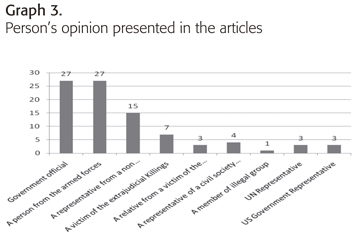

Graph 3. Shows the person's opinion main focus in the article; Graph 3a presents the main organization/institution mentioned in the articles. The discussion about the two graphs will be developed together as both findings refer, in the end, to the voices that were regularly considered as authoritative to give an opinion about this topic in the articles. The voice that more often appeared in the articles was a government official representative; followed in the second place by a representative of the Colombian Armed Forces; in the third place is found a representative from a non-governmental organization; and finally in just seven of the 90 articles analyzed, the main person focus was a victim or a victim's relative of the extrajudicial killings. Equally, confirming the findings of graph 3, is found that the organization/institution main focus in the articles was the armed forces, succeeding appeared the government institutions. Following the discussion about news sources in Chapter 2, the news coverage on the extrajudicial killings in El Tiempo is characterized by giving the privilege to institutionalized voices to appear in the articles. Although, the Western media has traditionally relied on official sources, especially in conflict situations, in the case of extrajudicial killings it is important to question how reliable it could be, in terms of presenting the reality of this major human right violation, to mainly present the opinion of the government and the military, as they are directly or indirectly involved in the perpetration of this situation. Kothari, (2010) highlights that the official sources will then have a greater power in framing the information described in the story. Moreover, the opinions presented from these sources can be contributing to frame the story in a bias way. In Cohen (2001) words this refers to one of the forms of denial:

"organizations and governments are perfectly justified in claiming that the event did not happened at all, or not as it was alleged to have happened, or that it might have happened without their knowledge" (p4).

Then, it could be said that the newspaper El Tiempo through relying mainly in official sources is offering a space where governments and organizations are publically able to express statements that symbolically are contributing to the construction of a denial about the Extrajudicial. This denial hampers the possibility of the society and the family members of the victims to knowing the truth about this grave human right violation. Furthermore, as these findings suggest, the voices of the victims' relatives of the Extrajudicial Killings are not considered authoritative news sources, therefore greater social awareness of how the family members of the victims suffer from this situation and how the wider society's solidarity bring support and relief.

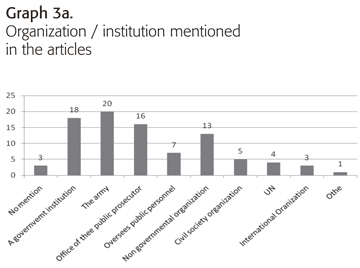

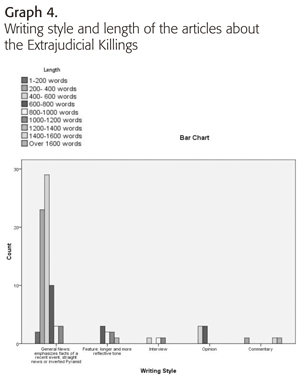

Graph 4. Presents the writing style against the length of the articles analyzed. Most of the articles were written in a general news journalistic style and the length ranged from 200 to 800 words. This writing style in an inverted pyramid way emphasizes facts, starting from the most important to the least important ones. The complexity of Colombian conflict and density of this topic reduced to be explained in normative writing style structures can weaken the intensity of the events and could lead to its trivialization (Zandberg, 2010). The writing style and length of the articles hardly contribute to provide a space where the personal testimony of the victims and family members of the victims could be publically expressed. An interesting fact was to find that in the very few articles where the victim or victim's relatives were mentioned, their opinion or story usually appeared in the last paragraphs of the articles, being the official voice the first one presented. Therefore, according to the inverted pyramid style the victims' opinion is presented as less relevant.

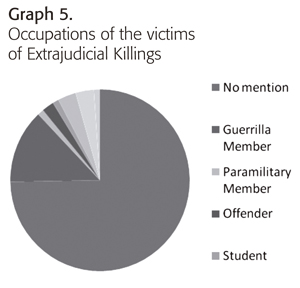

Graph 5. shows that in 68 of the articles analyzed there was no reference to the victims' occupations. However, when occupations were mentioned descriptions were primarily 'guerrilla member', or else 'unemployed' or 'offender'. This shows the lack of media attention to presenting bibliographical details of the victims; no effort was given to investigate and humanely treat the victim of the extrajudicial killings. Not even in the articles about the Soacha case attempted to recognize the victims and bring some dignity back to the lives of their relatives. Contrary, in many cases the victims were mistakenly describe as members of either of the illegal groups. As chapter 3 discussed, the way in which the story is being narrated can have a negative impact in the recovery process of the victims and family members of the victims of violence. Therefore, erroneous representations of the victims' identity, could generate in the victim's relatives more distress and magnify the already several mixed feelings of anger, injustice, isolation and impotence (Spiegel, 1988). It could be said that the press coverage of the Extrajudicial Killings, instead of providing recognition of the victims, is feeding feelings of injustice and impotence. On the other hand, when the articles referred to members of the military that had resigned due to this situation, a large space was dedicated to mention their bibliographical details. This finding are also suggesting that the newspaper's coverage of the extrajudicial killings does not challenge assumptions put forward by the sources cited, if the sources they used mentioned that the victims belonged to an illegal group, it dutifully present the information without investigating. It is evident a lack of an investigative framework that critically confront the information given with reality.

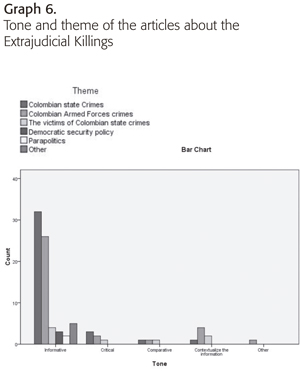

Graph 6. presents the tone against the theme of the article. Most of the articles' themes were the Colombian state crimes and the Colombian armed forces crimes. These themes were reported using an informative journalistic tone that privileged the descriptions of facts. The reporting on the extrajudicial killings was mainly treated in an uncritical and decontextualized manner. As discussed in Chapter 3, in the constant process of construction of the collective identity, the way in which journalists tell the stories of our daily happenings, the stories of pain and suffer inflicted by conflict, the stories about society, will impact the construction of the collective identity. The media has been important actors in assembling meaning to the collective memories, what is remembered, what is forgotten and why. Presenting important topics such as Colombian state crimes in an informative way could be contributing to a construction of the collective identity that have naturalized and legitimized violence as a social form of interaction. Moreover, the complexity of events in the Colombian conflict, a conflict that has already deeply damage the social relations of its inhabitants, deserves a more comprehensive coverage and analyses, where the information is historically contextualized and critically informed.

Conclusion

The general findings of this study regarding the media coverage on the Extrajudicial Killings in El Tiempo confirm that the newspaper mainly relied on official sources when reporting on the extrajudicial killings. This meant institutionalized voices were able to frame the story being told about this grave human right violation to the wider society. These findings confirm the hypothesis that the voices of the victims and relatives' victims of the Extrajudicial Killings are not considered authoritative news source. This situation undermines the healing effect that the narrative could have on the victims and family members of the victims of the Extrajudicial Killings by publically revealing their story of pain and suffering.

Survivors of violence, especially political violence, need to re-tell their story to the wider society, so that this could help in the process of rebuilding their identity which has been deeply affected by the traumatic situation. But it is not only to the victims of the violence that telling the story of injustice, suffering and pain brings relief; the collective identity of the whole society involved in the conflict benefits. Journalists through writing news stories are important sources in the construction of the collective identity; they retell the present and the past, re signify and deconstruct the daily happenings. Thus, in times of conflict and violence their role is important in the process of deciding what the society should remember, commemorate, deny and disavow in order to reconstruct the collective identity deeply damaged by violence.

The space and writing style used when reporting on the Extrajudicial Killings constrained the possibility of experiential testimonies of the victims' relatives to be presented in the story. Therefore the use of traditional news values and normative structures restricted the options of telling the story through other journalistic genres that could give a more comprehensive approach to the reality of the Extrajudicial Killings. Cote and Simpson, (2000) proposed when reporting on violence that new knowledge should be implemented to the journalistic routine. Furthermore, journalists' understanding of trauma should lead the news organization to find alternative approaches to the news stories about victims of violence. These authors propose that a better reporting about trauma, can enrich public awareness and empathy for the suffering of others.

The Colombian conflict presents several challenges to media organizations and journalists when reporting on conflict and victims of violence. The high level of violence that the conflict has reached has permeated different levels of society. The individuals and all the different organizations in society have been affected; therefore media organizations have been subjected to censorship coming from the different actors part of the conflict. Moreover, self-censorship seems to have been a shield that journalists use in order to avoid harassment from illegal groups when publishing stories which counter the interests of any of the actors' part of the conflict. The extrajudicial killings are a sensitive topic and reporting of the victims' stories of violence could be seen as upsetting issue.

To sum up, multidimensional, multidiscipli-nary, integrative framework for understanding trauma and its outcome is required. This understanding of the trauma requires the commitment of the national and the international community, as well as, the commitment of several social institutions in order to combat impunity and to work for the reconstruction of the collective identity deeply harmed in context of violence. The mass media, as important mediators between the wider society and the victims of violence certainly occupy an important role in people's understanding of conflict and in the healing process of the victims of violence.

This important role given to the media in the process of construction of collective memories and the collective identity therefore ascribes great social responsibility to journalists when reporting on conflict. This is heightened when covering news about trauma and violence. How the victims of violence are presented, how political violence is described, how the story is being told; all these aspects are constantly interacting and shaping the societies understanding of the conflict and violence, its roots and future actions to tackle it.

Several challenges and ethical questions emerge in the process of reporting on conflict. Different external limitations have been place upon media organizations and journalist while doing their job. In order to overcome this situation, Cottle (2006) proposes media reflexivity as a form of media self monitoring and reflection of its own practice:

"media reflexivity is vital for deconstructing 'spin and understanding the symbolic and rhetorical forms of power as well as for analyzing the media's seeming complicity with powerful interest"(Cottle, 2006 p.181).

Tester, (1994), referring to the moral responsibility of the mass media, describes that "the media are important channels through which individuals and audiences become aware of what is said to be right and wrong" (p.81). However, he highlights that there will always unanswerable about the relationship between media and the audience. Although media impacts on society, and especially media coverage of conflict impact on the audience is an area of study that would interest to deepen on, media reflexivity offers an interesting perspective that could encourage media organizations and media workers to critically reflect on their daily routine and the way they engage with the public.

This self reflective space, could certainly lead to a more humanistic and ethical way of understanding the people caught in the middle of the conflict through the thoughtful journalistic practices.

Bibliography

Allan, S. (1998), "News from nowhere: Televisual news discourse and the construction of hegemon", in A. Bell & P. Garret (Eds), Approaches to Media discourse, London, Routledge. [ Links ]

Amnesty International (2010), "Buscando justicia: Las madres de Soacha", [internet], available at: http://www.amnesty.org/es/library/asset/AMR23/002/2010/es/6da81c63-d8f3-414d-8e27-7c1b678f039c/amr230022010es.pdf, [accessed 20 August 2010] [ Links ]

Argentina's National Commission on Disappeared People (1986), Nunca más (Never Again), London, Faber and Faber. [ Links ]

Balabanova, E. (2007), Media, wars and politics: Comparing the incomparable in Western and Eastern Europe, Hampshire, England, Ashgate. [ Links ]

Bell, A. (1998), "The Discourse Structure of News Stories", in A. Bell & P. Garrett (Eds), Approaches to Media Discourse, London, Routledge. [ Links ]

Berelson, B. (1971), Content analysis in communication research, New York, Hafner Publishing Company Inc. [ Links ]

Bignell, J. (2002), Media Semiotics: An introduction, Manchester, Manchester University Press. [ Links ]

Bracken, P., Giller, J. & Summerfiel, D. (1995), "Psychological Responses to war and atrocity: the limitations of current concepts", Academic Department Of psychiatry [online] 40 (8) p.1082-1995. available at: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=MImg&_imagekey=B6VBF-3YS8BF9-6-2&_cdi=5925&_user=48665i&_ pii=027795369400i8iR&_orig=search&_coverDate=4%2F30%2F1995&_sk=999599991&view=c&wchp=dGLbVlb-zSkzV&md5=728298ee3adaffd446icaeb5074i057d&ie=/sdarticle.pdf, [accessed 20 August 2010] [ Links ]

Bryman, A. (2004), Social Research Methods, Oxford University Press, New York. [ Links ]

Bonilla, J. & Montoya, A. (2008), "The Media in Colombia: Beyond Violence and market-driven economy", in J. Lugo-Ocando (Ed), The media in Latin America, New York, Open University Press. [ Links ]

Caballero, M. (2000), "The Colombian Press under siege", in Harvard international Journal of press and politics, [online], 5 (3), p.90-95, available at: http://hij.sagepub.eom/content/5/3/90.full.pdf+html, [accessed 25 July 2010] [ Links ]

Carrillo, V. & Krucharz, T. (2006), Colombia terrorismo de Estado: Testimonios de la guerra sucia contra los movimientos populares, Madrid, Editorial Icaria/ Asociación Paz con dignidad. [ Links ]

Cohen, S. (2001), States of Denial: Knowing about atrocities and suffering, Cambridge, Polity press. [ Links ]

Comisión Colombiana de Juristas CCJ (2007), "Situación de Derechos Humanos y derecho humanitario 2002 -2006 Bogotá, Colombia", [internet], available at: http://nouvelles.asfquebec.com/pdf/CCJ% 20-%20Situacion%20DDHH%202006%20Espanol%20%20Feb%202007.pdf, [accessed 15 August 2010] [ Links ]

__. (2009), "Estadísticas violaciones de derechos humanos y violencia sociopolitica en Colombia", [internet], CCJ, available at: http://www.coljuristas.org/documentos/documentos_pag/Documento%20Alerta%20esp.pdf, [accessed 2 August 2010] [ Links ]

Coordinación Colombia Europa Estados Unidos CCEEU (2009), "Extra-judicial Executions: A reality that cannot be covered up", [internet], CCEEU, available at: http://ddhhcolombia.org.co/files/file/Ejecuciones/Ejeciones%20realidad%20inocultable%20en%20ingles(1).pdf, [accessed 20 May 2010] [ Links ]

Corporación Colectivo de abogados Luis Carlos Perez CCA (2009), "Informe de ejecuciones extrajudiciales en el departamento de Norte de Santander, Colombia", [internet], CCA, available at:http://www.movimientodevictimas.org/images/stories/pdfs/20090210%20INFORME%20EJECUCIONES.pdf, [accessed 3 August 2010] [ Links ]

Cote, W. & Simpson, R. (2000), Covering Violence: A guide to ethical reporting about victims and trauma, New York, Columbia University Press. [ Links ]

Cottle, S. (2006), Mediatized Conflict: Development in media and conflict studies, Berkshire, England, Open University Press. [ Links ]

Cooke, T. (2003), "Paramilitaries and the press in Northern Ireland", in Norris, P.; Kern, M. & Just, M. (Eds), The news media, the government and the public, London, Routledege. [ Links ]

Cruz, A. & Riviera, D. (2009), "La política de Consolidación de la Seguridad Democrática: Balance 2006-2008", en Analisis político, [online] 22 (66) p.59-80 Bogotá, Colombia, mayo-agosto 2009, pp.59-80, available at: http://www.scielo.unal.edu.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0i2i-47052009000200003&lng=en&nrm=iso, [accessed 10 July 2010] [ Links ]

Danieli, Y. (2009), "Massive trauma and the healing role of reparative justice", in Journal of Traumatic Stress, [online], 22 (5), p. 351-357, available at: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/jts.20441/pdf, [accessed 29 May 2010]. [ Links ]

Fiske, J. (1990), Introduction to communication studies, London, Routledge. [ Links ]

Forero, G., Arango, M., Llana, L. & Serrano, M. (2010), "Colombian Media in the XXI centrury: The Reconquest by Foreign Investment", in Persona y bioética [online]. 13, (1), p.59-76, available at: http://personaybioetica.unisabana.edu.co/index.php/palabraclave/article/download/1634/2070, [accessed 5 August 2010] [ Links ]

Fundación para la Educación y el Desarrollo FEDES (2008), "Soacha: Diagnóstico: Contexto, cifras, violencia intrafamiliar, derechos humanos, empleabilidad y vivienda", [internet], FEDES, available at: http://www.fedescolombia.org/docs/12_Diagnostico.pdf, [accessed 5 August 2010] [ Links ]

__. (2010). "Soacha: La punta del Iceberg: Falsos Positivos e Impunidad" [internet] FEDES, available from: http://www.fedescolombia.org/docs/Informe%20Falsos%20Positivos%20e%20Impunidad.%20FEDES.pdf, [accessed 25 May 2010] [ Links ]

Fundación Seguridad & Democracia FSD (2009), "Balance de seguridad nacional 2009 Colombia", [internet], FSD, available at: www.seguridadydemocracia.org, [accessed 2 August 2010] [ Links ]

Gilbert, P. (1992), "The oxygen of publicity: Terrorism and reporting restrictions", in Belsey, A. & Chadwick, R. (Eds), Ethical Issues in Journalism and the Media, London, Routledge. Ch. 10. [ Links ]

Graber, D. (2003). "Terrorism, Censorship and the ist Amendment: In search of policy guidelines", in Norris, P.; Kern, M. & Just, M. (Eds), The news media, the government and the public, London, Routledege. [ Links ]

Halliday, F. (1999), "Manipulation and Limits: Media coverage of the Gulf War, 1990-91", in Allen, T. & Seaton, J. (Eds), The Media of conflict: War reporting and representations of Ethnic Violence, London and New York, Zed Books. Ch. 6. [ Links ]

Hallin, D. & Papathanassopoulos, S. (2002), "Political clientelism and the media: Souther Europe and Latin America in comparative perspective", in Media, Culture & Society [online], 24 (2), p.175-195, available at: http://mcs.sagepub.com/content/24/2/175, [accessed 25 July 2010] [ Links ]

Halbwachs, M. (1992), On collective memory, United States of America, The university of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Human Rights Watch (2010), "Colombia Paramilitaries' Heirs: The News Face of Violence in Colombia", [internet] Human Rights Watch, available at: http://www.hrw.org/en/reports/2010/02/03/paramilitaries-heirs, [accessed 25 May 2010] [ Links ]

Hughes, S. & Lawson, C. (2005), "The barriers to media opening in Latin America", in Political Communication, [online], 22 (2), p. 9-25, available at: http://web.ebscohost.com/ehost/detail?vid=4&hid=123&sid=67202fae-2f39-458b-8951-8dabcba0a2fb%40sessionmgr110&bdata=Jmxhbmc9ZXMmc2l0ZT1laG9zdC1saXZl#db=a9h&AN=16495649, [accessed 7 August 20i0] [ Links ]

Jasmin, H. (2009). "Legalizing the illegal: Paramilitarism in Colombia's post paramilitary era", in NACLA report on the Americas, 42 (4), p. 12-39, available at: https://nacla.org/node/5939 [accessed 20 August 2010] [ Links ]

Jenkins, P. (2003), Images of terror: What can and cant know about terrorism, New York, Walter De Gruyter. [ Links ]

Keeble, R. (1994), The newspapers handbook, New York, Routledge. [ Links ]

Kothari, A. (2010), "The Framing of the Dafur conflict in the New York Times: 2003-2006", in Journalism Studies, [online], 11(2), p. 209 -224, available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14616700903481978 [accessed 28 May 2010] [ Links ]

Leech, G. (2008), "Distorted Perceptions of Colombian's Conflict", in Media Accurancy on Latin America, [online], available at: http://www.mediaaccuracy.org/node/58, [accessed 20 May 2010] [ Links ]

Lifton, R. & Faust, D. (2009). "Tugging Meaning Out of Trauma", in Nieman Reports, [online], 63(4), p.69-73, available at: web.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=15&hid=119&sid=cab0i397-c828-4b3d-b30a7d85183d686d%40sessionmgr111m [accessed July 29, 2010]. [ Links ]

Lykes, M. & Brabeck, M. (1993), "Human rights and mental health among Latin American women in situations of state sponsored violence", in Psychology of women quarterly, 17 (4), p.525-544, available at: http://web.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=2&hid=112&sid=e20757dd-b2ce-42ib-adb3-908c28895bi3%40sessionmgrii0, [accessed 10 August 2010] [ Links ]

Ministerio de Defensa [Colombian Ministry of Defense], http://alpha.mindefensa.gov.co/ [ Links ]

Martin-Baro, I. (2003), Poder, ideologia y Violencia, Madrid, Trota Editorial. [ Links ]

McQuail, D. (2003), Mass communication theory, London, Sage [ Links ]

Munczek, D. & Tuber, S. (1998 ), "Political repression and its psychological effects on Honduran children", in Clinical Psychology Doctoral subprogram, Graduate Center of the City of New York.. New York, 47 (11) p.1699-1713, available at: http://sciencedirect.com/science">sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=MImg&_imagekey=B6VBF-3V8CRDC-8-1&_ cdi=5925&_user=486651&_ pii=0277953698002524&_orig=search&_coverDate=12%2F31%2F1998&_sk=99952998&view=c&wchp=dGLzVzz-zSkzS&md5=oo752de36o2c958f2f885d7bf 977i3a9&ie=/sdarticle.pdf, [accessed 13 July 2010] [ Links ]

Ospina, C. (2007), El terrorismo de Estado en Colombia, Venezuela, Fundación Editorial El Perro y La Rana. [ Links ]

Pion-Berlin, D. (1989), The ideology of state terror: Economic Doctrine and Political repression in Argentine and Peru, United Kingdom, Lynne Rienner Publishers. [ Links ]

Restrepo, J., Spagat, M. & Vargas, J. (2006) "The severity of the Colombian conflict: Crosscountry datasets versus New Micro-data", in Journal of Peace research, [online], 43 (1), p.99-115, available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/pdfplus/27640254.pdf?acceptTC=true, [accessed 15 June 2010] [ Links ]

Roeh, I. (1989 ), "Journalism as Storytelling: Coverage as Narrative", in American Behavioral Scientist, [online], 33 (2), p.162-168, available at: http://pao.chadwyck.co.uk/PDFA282843764814.pdf, [accessed 5 Augutst 2010] [ Links ]

Rojas, C. (2009), "Securing the state and developing social insecurities: the securitization of citizenship in contemporary Colombia", in Third World Quarterly, 30 (1), p. 227-245, available at: http://web.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=2&hid= i09&sid=c270bdi0-bf88-40d6-b70d-dd9b7473797b%40sessionmgri04, [accessed 15 August 2010] [ Links ]

Roniger, L. & Sznajeder (1999), The legacy of human rights violations in the Southern cone: Argentina, Chile and Uruguay, New York, Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Schlesinger, P. (1991), Media, state and nation: Political violence and Collective Identities, London, Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Spiegel, D. (1988), "Dissociation in Hypnosis in post traumatic stress disorders", in Journal of traumatic stress, 1 (1), p.17-33, available at: http://www.springerlink.com/content/j2435h7wiioi63xo/fulltext.pdf, [accessed 18 July 2010] [ Links ]

Staub, E. (2006), "Reconciliation after genocide, Mass Killing, or intractable Conflict: Understanding the roots of violence, psychological recovery and steps towards a general theory", in Political Psychology, [online] 27, (6), p.867-894, available at: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/i0.iiii/j.i467-922i.2006.0054i.x/pdf, [accessed 7 June 2010] [ Links ]

United Nations UN (2010), "Report of the Special Rapporteour on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions", Philip Alston, [internet], United Nations (UN), available at: www.extrajudicialexecutions.org/application/media/Colombia%20Report%20A.HRC.14.24.Add.2_en2.pdf, [accessed 2 August 2010] [ Links ]

Van Dijik, T. (1988), News as Discourse, New Jersey, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. [ Links ]

Verdoolaege, A. (2005), "Media representations of the South African truth and reconciliation commission and their commitment to reconciliation", in Journal of African Cultural Studies, [online], 17 (2), p.181-199, available at: http://pdfserve.informaworld.com/527850_75i3i3002_727495269.pdf, [accessed 10 June 2010] [ Links ]

Williams, K. (1992), "Something more important than truth: Ethical issues in war reporting", in Belsey, A. & Chadwick, R. (Eds), Ethical Issues in Journalism and the Media, London, Routledge. Ch. 10. [ Links ]

Zandberg, E. (2010), "The right to tell the (right) story: journalism, authority and memory", in Media, Culture and Society, 32 (1), p. 5-24, available at: http://mcs.sagepub.com/content/32/1/5, [accessed 13 August 2010] [ Links ]

Zelizer, B. (1993), "Journalists as Interpretive Communities", in Critical Studies in Mass Communication, [online], 10 (3), p. 219-237, available at: http://web.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=2&hid=108&sid=f40aac09-7ced-425d-b488-ef1927da9464%40sessionmgri04, [accessed 7 August 20i0] [ Links ]

Appendix I

CODING MANUAL

Person focus I

- Government representative

- Armed forces representative

- Non- governmental Organization representative

- Victim of extrajudicial Killings

- Victim's relative of extrajudicial killings

- Civil society organization representative

- Member of illegal group

- UN representative

Writing Style

- General News

- Feature

- Chronicle

- Interview

- Opinion

- Commentary/criticism

Occupation of the victim

- Ex-Guerrilla Member

- Ex-Paramilitary Member

- Military force Member

- Offender

- Student

- Employed

- Unemployed

- No mention

Organization/institution

- Government institution

- The Army

- Office of public prosecutor

- Oversees public personnel

- Non-Governmental organization

- Civil society Organization

- UN

- International Organisation

- Other

Length of the article

- 1- 200 words

- 200-400 words

- 400-600 words

- 600-800 words

- 800-1000 words

- 1000-1200 words

- 1200-1400 words

- 1400-1600 words

Theme of the article

- Colombia state crimes

- Colombian armed forces crimes

- The victims of the Colombian state crimes

- Democratic Security Policy

- Parapolitics

- Other

Tone

1. Informative 2. Critical 3. Comparative 4. Contextualized 5. Other

Appendix II

CATEGORIES OF ANALYSIS

I. Person focus I in the article: Refers to the main person's opinion presented in the articles.

- Government representative: When person's main opinion presented in the article is the president, the vice-president a minister, a senator a congressman.

- Armed forces member: When person's main opinion presented in the article Coronel, general or a soldier.

- Non-governmental Organization representative: When person's main opinion presented in the article a representative from a national or International NGO.

- Victim of extrajudicial Killings: When person's main opinion presented in the article is the person who has been victim of the extrajudicial executions.

- Victim's relative of extrajudicial killings: When person's main opinion presented in the article is a victims' family member.

- Civil society organization representative: When person's main opinion presented in the article is someone who represents a social movement, or indigenous organization or a trade union.

- Member of a illegal group: When person's main opinion presented in the article is a member of the guerrilla or paramilitary groups.

- UN representative: If the person's opinion presented in the article is a representative of the UN

- US Government representative: When person's main opinion presented in the article in the is the US government representative.

- Other

II. Organizations and Institutions Focus I mentioned in the Article: Refers to the main organization refer to in the articles.

- Government Institution: If the institution mentioned was the presidency of the republic; the ministry of defense, the senator and congress.

- The army: If the institution mentioned was the Armed forces of Colombia or the military.

- Office of the public prosecutor: In charge

- Oversees public personnel: A Colombian public institution which role is to be a watchdog of the public sector workers.

- NGO (non-governmental organization Amnesty, Human rights)

- Civil Society Organization: A social movement, indigenous organizations, victims' association.

- UN: United Nations

- International Organization

- Other

III. Writing Style

- General News: Emphasizes facts of a recent event, straight news and inverted Pyramid where the most important facts are at the beginning of the article and the least important in the end.

- Feature: Longer article and more reflective tone

- Interview: A discussion between two parts; a conversation between the journalist and someone else consider relevant to discuss the topic presented in the article.

- Opinion: When the journalist opinion is directly presented in the article.

- Commentary/criticism: Any story that offers a first person opinion

IV. Length of the article

- 1- 200

- 200- 400 words

- 400- 600 words

- 600- 800 words

- 800-1000 words

- 1000-1200 words

- 1200-1400 words

- 1400-1600 words

- 1600 and Over

V. Occupation of the Victim: If the victim's occupation or activity mentioned refers to:

- Ex-Guerrilla Member

- Ex-Paramilitary Member

- Military force Member

- Offender

- Student

- Employed

- Unemployed

- Other

VI. Theme of the Article: By looking at the number of paragraphs that the articles focus on one of the following topics:

- Colombian state Crimes: displacement, disappearances.

- Colombian Armed Forces crimes: The extrajudicial killings

- The victims of Colombian state crimes: Any topic related to the victims, for example, about the victim's reparation law, an event organized for the victims.

- Democratic security policy: If it refers to the security polices that the government is implementing

- Other.

VII. Tone / Disposition of the Article

- Informative: Describe the facts