Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Investigación y Educación en Enfermería

Print version ISSN 0120-5307

Invest. educ. enferm vol.30 no.3 Medellín Sept./Dec. 2012

ARTÍCULO ORIGINAL / ORIGINAL ARTICLE/ ARTIGO ORIGINAL

Perception of the quality of life of family caregivers of adults with cancer

Percepción de la calidad de vida de cuidadores familiares de adultos con cáncer

Percepção da qualidade de vida de cuidadores familiares de adultos com câncer

1Carmen Liliana Escobar Ciro

1 RN, M.Sc., Proffesor, Nursing Faculty, Universidad de Antioquia, Colombia. email: clilianae@gmail.com.

Receipt date: October 3rd 2011. Approval date: May 15th 2012.

Subventions: none.

Conflicts of interest: none.

How to cite this article: Escobar-Ciro CL. Perception of the quality of life of family caregivers of adults with cancer. Invest Educ Enferm. 2012;30(3):320-329

ABSTRACT

Objective. To describe the perception of the quality of life of family caregivers of adult individuals with cancer. Methodology. Descriptive study conducted in 2008 with a convenience sample of 209 caregivers of adults with cancer who attended oncology units in Medellín, Colombia. The instrument proposed by Ferrell et al., was used to measure the quality of life of the family member caring for the patient, which evaluates quality of life through 37 items that integrate their meaning in the: physical (5 items), psychological (16 items), spiritual (9 items), and social (7 items) well-being. The evaluation of each item is conducted through a Likert-type scale from 1 to 4. Interpretation of the total score and by subscale is an inverse relationship between the score and the deterioration of the caregiver's state. Results. The participants perceive as most affected the dimensions from the physical (83.2%), psychological (80.9%), and social well-being (75.6%) quality of life scale. The spiritual dimension was the least affected (9.1%). Conclusion. Caregivers of adult patients with cancer have a negative perception of their quality of life. Nursing should participate to support these caregivers

Key words: quality of life; caregivers, adult; neoplasms.

RESUMEN

Objetivo. Describir la percepción de la calidad de vida de cuidadores familiares de personas adultas con cáncer. Metodología. Estudio descriptivo realizado en 2008 con una muestra por conveniencia de 209 cuidadores de adultos con cáncer quienes asistieron a unidades de oncología de Medellín, Colombia. Se empleó el instrumento propuesto por Ferrell et al. para la medición de la calidad de vida del familiar que brinda cuidados al paciente, a partir de 37 ítems que integran su significado en los bienestares: físico (5 ítems), psicológico (16 ítems), espiritual (9 ítems) y social (7 ítems). La evaluación de cada ítem se efectúa mediante una escala de 1 a 4 tipo Likert. La interpretación del puntaje total y por subescala es una relación inversa entre el puntaje y el deterioro en el estado del cuidador. Resultados. Las dimensiones más afectadas, según la percepción de los participantes, son: la escala de calidad de vida física (83.2%), psicológica (80.9%) y de bienestar social (75.6%). La dimensión espiritual fue la menos afectada (9.1%). Conclusión. Los cuidadores de pacientes adultos con cáncer tienen una percepción negativa de su propia calidad de vida. Se requiere que enfermería participe en el apoyo a estos cuidadores.

Palabras clave: calidad de vida; cuidadores; adulto; neoplasias.

RESUMO

Objetivo. Descrever a percepção da qualidade de vida de cuidadores familiares de pessoas adultas com câncer. Metodologia. Estudo descritivo realizado em 2008 com uma mostra por conveniência de 209 cuidadores de adultos com câncer que assistiram a unidades de oncologia de Medellín, Colômbia. Empregou-se o instrumento proposto por Ferrell et ao. para a medição da qualidade de vida do familiar que brinda cuidados ao paciente, o qual valoriza a qualidade de vida mediante 37 itens que integram seu significado nos bem-estares: físico (5 itens), psicológico (16 itens), espiritual (9 itens) e social (7 itens). A avaliação de cada item se efetua mediante uma escala tipo Likert de 1 a 4. A interpretação da pontuação total e por sub-escala é uma relação inversa entre a pontuação e a deterioração no estado do cuidador. Resultados. Os participantes percebem como mais afetadas as dimensões da escala de qualidade de vida física (83.2%), psicológica (80.9%) e de bem-estar social (75.6%). A dimensão espiritual foi a menos afetada (9.1%). Conclusão. Os cuidadores de pacientes adultos com câncer têm uma percepção negativa de sua qualidade de vida. Requer-se que enfermaria participe no apoio a estes cuidadores10445O contexto cirúrgico transoperatório.

Palavras chaves: qualidade de vida; cuidadores; adulto; neoplasias.

INTRODUCTION

Significant increase of chronic conditions like cardiovascular and pulmonary disease, cancer, diabetes, osteoarthritis, Alzheimer's disease, among others, leads to increasing numbers of people dependent on their families for their recovery, support, or accompaniment. In Colombia, cancer occupies the third place in mortality for adults, with special emphasis on those older than 60 years of age1. It is known that the increase of all these conditions brings as a consequence physical, psychological, social, and spiritual alterations of the quality of life of the sick and in recent years, it has become of interest to study how this situation affects the quality of life of the family caregivers. We must face the reality that a growing population with chronic and debilitating

disease, who bring with them the need to address the possibility that many of these people will have to be cared for at home by the family. Individuals with oncologic disease ask to be cared for at home and the therapies take place in outpatient environments or at home in 80% of the cases.2 The experience of being a family caregiver of someone who is suffering a disease like cancer can affect in different forms all the personal dimensions, which is why it is important to investigate about their quality of life. The concept of quality of life is a complex, multidimensional, multidisciplinary construct with multiple interpretations. Quality of life is, in essence a subjective sense of well-being that includes physical, psychological, social, and spiritual dimensions.3

For Giraldo and Franco4, this concept is not unique and it is influenced by the circumstances accompanying the individual at every moment; therefore, it is - according to the authors - an individual and dynamic concept where the perception of the family caregivers occupies a fundamental place. The World Health Organization5 defines it as 'the perception individuals have of their place in existence, within the context of culture and the value system in which they live and in relation to their objectives, expectations, norms, concerns.' Due to the increase of chronic disease and the lack of protection of the family caregivers by the healthcare system, the situation becomes complex for the people enduring the experience, as well as for the family member assuming their care.6 For Cardona and Agudelo,7 the concept of quality of life, given that it is a complex social phenomenon and a problem of personal perception of the level of well-being, must consider objective and subjective variables, which depend on feelings and can only be seen through the interested parties.

Measuring quality of life through multidimensional measurements permits the incorporation of objective and subjective elements. For individuals with chronic disease, including cancer and their families, investigations in this aspect have contributed significantly to recognizing the impact of the role of caring and to understanding the disease.8

This study considered the concept of 'Quality of life of the caregivers' proposed in the model of quality of life applied to families by Ferrell et al., a model that emerged from qualitative and quantitative studies conducted with cancer patients and cancer survivors and with family caregivers (FC), where quality of life is mainly a subjective sense of well-being that includes the physical, psychological, social, and spiritual dimensions8; as noted, this definition incorporates the individual's own perception.

Investigating about the quality of life of FCs contributes care practice and knowledge to the nursing discipline in the field, especially, in the home environment. With the study findings, we seek greater understanding of the implications of the FC's role in caring for the sick family member. The aim of this study was to describe the perception on the quality of life of FCs of adult individuals with cancer who attend oncology support centers in the city of Medellín.

METODOLOGY

A quantitative descriptive-type study was conducted. A convenience sample was taken of 209 people who had spent more than three months as family caregivers of adult individuals with cancer and who were attending oncology support programs in four institutions in the city of Medellín, Colombia, during 2008.

In self-reported manner, information was obtained on: a) socio-demographic variables b) degree of dependency of the person cared for under situations of chronicity: The PULSES evaluation scale was used (P= pathology or physical condition stability, U= use of upper limbs, L= locomotion or function of lower limbs, S= sensory function, E: elimination or sphincter control, S= socialization ability).8 Each function is scored from 1 to 4 (1= independent, 2= requires mechanical support (apparatus), 3= requires mechanical support and from another person, and 4= completely dependent). It permits classifying individuals with slight, moderate, and severe dependency; and c) quality of life: the instrument by Ferrell et al.,8 'Quality of Life - family version' was used. This scale has a reliability coefficient of 0.89, measure with Cronbach's alpha. It has been used in Latin populations in studies in four countries of the region.6 The instrument comprises 37 items, which describe quality of life in the physical (5 items), psychological (16 items), social (9 items), and spiritual (7 items) dimensions. Each item has four response options that go from 1= no problem to 4= too much problem. Of the 37 items, 21 must be reversed to obtain the total score. This instrument was adapted by the group of professors from the Line of Research on Chronic Patient Care of the Faculty of Nursing at Universidad Nacional de Colombia.

Application of the instruments took place at oncology support institutions authorizing such. By using informed consent signed by each of the participating caregivers, these were informed of the study objectives, the confidentiality of the information, respect to autonomy, voluntary participation, the use of data for academic purposes, and the return of the results to the participants and institutions.

RESULTS

The general characteristics of the caregivers reveal that 74.2% are females; in their different roles as daughters 29.7%, wives 21.1%, and sisters 13.9%. Some 57.9% of the participants were between 36 and 59 years of age, another 27.3% were between 18 and 35 years of age, and the remaining 14.8% were 60 years of age and above. A total of 97.1% know how to read and write; level of education: 30.6% with primary school, 46.4% with secondary school, and 22.5% with technical or university education.

Four of every five caregivers (86.6%) belonged to socioeconomic levels 1, 2, and 3. Some 73.2% are sole caregivers; 44% have spent less than six months in this task, another 34.4% have cared for their family member for 7 to 18 months, while the remaining 21.5% has spent over a year and a half in that activity. Regarding occupation, the results reveal that most (50.2%) of these caregivers is dedicated to household work, followed by 20.6% who are employed, 17.7% independent workers, 6.2% students, and 5.3% engaged in other activities. In terms of the degree of functional dependence of the person cared for (PULSES scale), most caregivers are in charge of patients with moderate dependency in 42.6% of the cases; slight dependency in 31.6%, severe dependency in 24.8%, and no information was gathered from 1% of the cases.

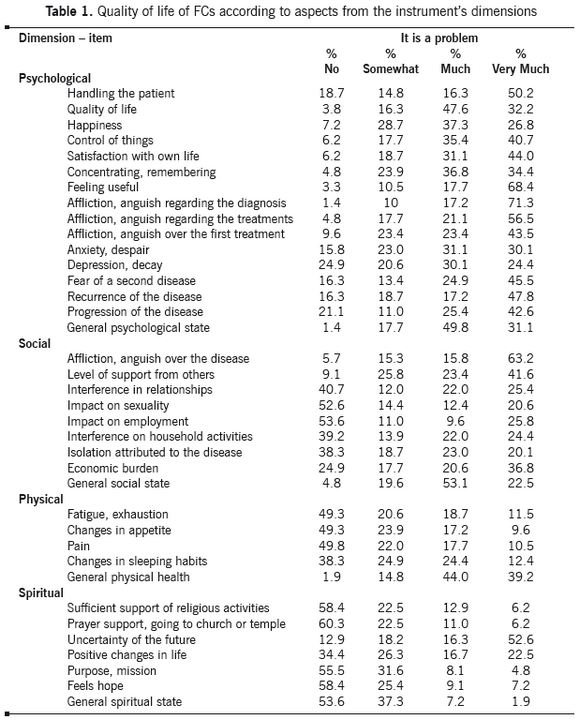

Regarding the quality of life of the caregivers studied, it may be noted in Table 1 that they perceive that all their dimensions are affected.

Psychological Dimension. Quality of life in this dimension showed an average of 39.8±8.8,

which is far from the maximum score of 64 for this dimension, meaning that FCs perceive a negative alteration of their quality of life in this aspect. The most affected items were those related to having to deal with their lives as a result of their relative's disease (50.2%), affliction and anguish produced by the relative's diagnosis (71.3%), regarding treatments (56.5%), fear of recurrence (47.8%), and progression of the disease (42.6%).

Social dimension. The results showed an average of 23.9±6.6. Bearing in mind that the maximum score possible in this dimension is 36, it may be noted that caregivers perceive social well-being as negatively affected, especially in that related to affliction and anguish provoked by their relative's disease with 63.2%, and the economic burden incurred as a result of the disease and the treatments with 36.8%; the perception of the general social state is perceived as a problem or very much a problem for this group of caregivers at 75.6%

Physical dimension. From this dimension, the study showed an average score of 15.4±3.6, and if we bear in mind the maximum possible score of 20 points, it means that these caregivers are at a low risk of acquiring physical problems. Among the problems reported by the participants, it is noted that the caregivers report few problems related to pain (49.8%), fatigue and exhaustion and changes of appetite (49.3%), and changes in sleeping habits (38.3%); in spite of that, the perception of general physical health is not good for this group of caregivers.

Spiritual dimension. This dimension yielded an average of 21.5±3.6, with a possible maximum score of 28, representing an important aspect to strengthen in all the caregivers. Likewise, most classified as positive the care experience related to support perceived by attending religious activities (58.4%), going to the temple or church (60.3%), sensation of a purpose in life (55.5%), feeling hope (58.4%), and perception of positive changes (34.4%). Uncertainty, on the contrary, is seen as a negative aspect present in most of the caregivers with 52.6%.

DISCUSSION

The results from this study, like others8-10, reflect that many of the caregivers are women, in their different roles as daughters, wives, sisters, middle aged, dedicated to household work, and mostly from socioeconomic levels 1, 2, and 3. The work imposed on women by society is reaffirmed, who continue having a priority role in all tasks associated to caring for the family, a worrisome situation, inasmuch as it manifests the possible exhaustion as a consequence of the role they play, added to other tasks of everyday life and, in some cases, to interference with labor occupations. People who include caring for adults in their obligations are women from lower educational levels and less favored social classes. The author states that the less favored socioeconomic levels most frequently encounter the need to care for a relative with health problems, given that lack of economic resources keeps them from hiring another person, which exposes them to stress, anguish and to negative effects for their physical and psychological health.9 The impact of caring for an adult with chronic disease generates problems that clash with the quality of life of the individuals and family groups.

Regarding the degree of schooling, it was noted that 97.1% know how to read and write, most having basic primary and secondary education, which becomes a positive indicator because it facilitates interventions to acquire knowledge and develop skills by this group of caregivers. We must consider that a middle level of schooling supposes a level of preparation that can be availed for advisory and permanent accompaniment to improve the skills required to offer care. Schooling is quite important in caregivers6; it determines the level of support or the presence of difficulties in the work they do9 and it also permits identifying strategies to be used in training and education processes.10 According to Sánchez, the caregiver must have a sufficient degree of preparation for this responsibility, which includes - among others - participation in decisions, knowledge of the disease, of the treatments, follow up, resources,

and regarding the support network10 the level of awareness is necessary to understand the reality of the people cared for, their needs, strengths and weaknesses, fundamental aspects in the care relationship.11 The importance of these findings lies in that with a level of education as that found, this becomes a definite support to perform the caregiver's role.

Also, the functional capacity of the person cared for is within moderate dependency, which influences in important manner on the caregiver, given that as individuals become more dependent, the caregiver's loss of control is more visible, with feelings of anger, rage, and frustration; additionally, the demands for care considerably reduce the caregiver's leisure time, as well as family and social relationships.11,12 We cannot ignore that family caregivers often encounter this role without the necessary skills and knowledge, which translates to greater stress and overload. Knowing the degree of functionality of the people with cancer receiving care, permits predicting the overload and stress levels and, hence, the higher risk the caregivers have of falling ill. The role of nursing is basic to provide comprehensive support to family caregivers at risk of claudicating in the care, with emphasis on preventing fatigue, and the physical and emotional alterations that may arise from the sick person's greater dependency.13

Regarding the quality of life, the caregivers in this study perceive all its dimensions affected; the psychological and social well-being are the most negatively affected; the physical and spiritual well-being are perceived more positively by most of the caregivers in this group. In the psychological well-being, matters related to affliction and anguish produced by the diagnosis given to their relative, related treatments, dealing with a person with a chronic disease, fear of recurrence, propagation of the disease, and the possibility of a second disease were felt as most affected. The aforementioned is similar to that found in a study on the quality of life of family caregivers caring for children under situations of chronic disease, where the greatest

affectation of the caregivers is given by dealing with the disease and managing with anguish and anxiety.14 In another study comparing the quality of life of family caregivers of individuals with HIV-AIDS, it was concluded that the groups compared presented a marked decay of the quality of life in the psychological aspect, due to the role they played and by being exposed to stress, depression, isolation, and emotional load.6 Often, when the family faces the reality of the chronic disease, it is subjected to contradictory feelings, which depending on each person and family, it will have to be considered that upon the progressive loss of the patient's capacities, both the patient and his family will have moments of anguish, despair, depression, dejection, with subsequent acceptance of the loss and generation of new ties.15

The emotional tension and associated health problems appear when a high level of demands is perceived for the caregiver along with scarce resources to control the situation. The negative impact within the psychological sphere may also be related to the degree of dependency of the person cared for, which in this group was classified as moderate and the fact that most (73.2%) were sole caregivers. It is important to recognize the devastation of the initial diagnosis of a disease like cancer that remains through the experience of living in this situation and the possibility of survival in the long term, a reality that must be considered, by the sick person and his caregiver.8 Most caregivers in this study perceive negatively their general psychological state, but in spite of that 86.1% manifested feeling useful in the work they perform, which may be related to the role, with altruistic purposes, which they assume due to gratitude, or because of the love they feel for their sick relative.16 When caregivers manage to maintain a balance in the psychological aspect, it is when several mechanisms are available to control the experience, like social supports, satisfactions, and the result of caring, which is why it is important for them to dedicate time and energy to activities different from their role; for periodic rests to be programmed; and for them to obtain psychological support from the start of their activities as caregivers. The nursing professional must have the ability to provide adequate, opportune, clear, and true information, which diminishes feelings of uncertainty both in patients as in their families.

The quality of life of this group of caregivers of people with cancer has a negative affectation perception in the social dimension; the affliction and anguish provoked by their relative's disease is perceived as most negative, followed by the economic burden incurred as a result of the disease and the treatments, the social state in general is perceived as a problem or very much a problem for caregivers of this group. It is worth considering that most of the treatments of people with cancer are in outpatient manner and - often - the caregivers must accompany them during long sessions and workdays not only because of the treatment but because of the conditions derived from the disease, a situation that added to the travel time to the institutions becomes a factor that weighs on the economic resources, especially when most of the caregivers in this study are from socioeconomic levels 1, 2, or 3 and any additional economic burden supposes greater levels of anguish. The family, economic, and social impacts can result more critical for the less favored classes, people without labor occupations tend to identified as caregivers, given the continuity between household chores and those of informal healthcare17; this coincides with the research conducted by álvarez6 where affliction and anguish endured by the caregiver because of the relative's disease, as well as the economic burden become factors of greater social impact. The social dimension may be affected in the caregivers due to the lack of social support, lack of economic resources, and little rest. Caregivers need to dedicate time and energy to activities different from the role of caring, for which healthcare institutions must offer support alternatives to caregivers or enhance those already existing

As far as the physical dimension most caregivers in this group perceives a negative degree of affectation in the general physical aspect; however, there are few problems related to

Invest Educ Enferm. 2012;30(3) . 327 fatigue, changes in sleeping habits, pain, or changes in appetite, this may be due to the fact that 44% of the caregivers in this study have been involved in caring activities for less than six months, a situation that should, nevertheless, be watched because as stated by Bastida,15 in the main caregiver there is a constant increase of responsibilities and diminished time for rest and leisure, due to activities with the patient like medication, hygiene, and feeding, which is why many time caregivers do not care for themselves, gradually losing their independence and ultimately losing for some time their own life project, with consequences for their physical and psychological health. As noted by Pinto18, facing a chronic disease generates problems not only for the patient, but also for the family group, which often rivals their quality of life, generating sleep and rest alterations, stress, depression, and sadness, but maintaining hope. Also, Betty Ferrell,8 in a study on the quality of life of patients with ovarian cancer and their support needs, states that the caregivers of these women reflect little concern for their own physical well-being, but do worry about the psychological, social, and spiritual aspects of their experience. It is important to consider, as suggested by the author, that the physical well-being after a cancer diagnosis is influenced in great part by the symptoms associated to the disease and its treatment. This is relevant to the extent the disease advances, which is why the individual will experience more adverse symptoms, which will have repercussions on the caregiver's quality of life. It is worth noting that care giving, in great part, is determined by the skills of the main caregiver to manage stress, her capacity to identify social support, and her coping strategies.18-20

We must recognize the importance of being attentive to needs that may arise in this aspect as time progresses in this work. It is important for nursing to be present in obtaining support services and to seek to improve the caring skills of these people through workshops and training, which additionally motivate caring for themselves. For the spiritual dimension the group of caregivers mostly perceived it as without a problem

(90.9%); the benefits reported by this group of caregivers are related to finding a sense to their lives, the sensation of feeling useful for society, the feeling of accomplishment, and the learning acquired in the world of caring. It is important to remember that according to some authors, spiritual well-being is manifested by the ability to maintain hope and obtain meaning through the caring experience, which is characterized by uncertainty and represents a potential.21 Most caregivers from this group feel they have complied with a purpose in life that permits them important personal growth and, in some cases, it even enhances family union, and it is perceived as less complex depending on the support available for the caregivers; through studies, a positive relationship has been demonstrated between the levels of spiritual well-being and the strength related to health.22 Sánchez23 indicates that these types of experiences permit caregivers to learn about the value of life and health in daily life and on the closeness of death, and in that link there is protection, recognition, gratitude, complicity, and dependency. In some cases24, it is evident that being a caregiver permits growing spiritually and emotionally, understanding many aspects of life, comprehending the value of the family and of solidarity in spite of difficulties, and that the experience also supposes human and affective compensation.

Love and affection become the main focus of comprehensive care, for some caregivers, this influences positively on the patient's behavior. The decision to respond freely and willingly to the call of another allows them to find their own identity and the best of themselves.25 According to Ferrell,8 spiritual well-being is very important for caregivers and it is through faith and hope that they find positive meaning to their experience. Other authors agree with this, for whom the benefits reported by caregivers are related to finding sense to their lives, the sensation of feeling useful to society, the feeling of accomplishment, and retribution to whom during another moment contributed in their lives, in addition to the learning they acquire on the world of health and caretaking.4,24

Nursing recognizes as essential the interaction with the person cared for and with the caregiver, which is why it is imperative to have greater knowledge of the spiritual dimension of caring when addressing oncologic disease, where suffering, pain, feelings of loss, fear, and death threat are always present.26 Spiritual well-being is related to faith, beliefs, and meanings and nurses, within a multidisciplinary team, must bear in mind all this in their care plans, listening to patients and their families and observing their responses to create a real environment of trust and the best quality of life for oncology patients, their families, and their caregivers23. Regarding the feeling of uncertainty, manifested by 52.6% of the caregivers, it can be a source of stress, above all during the acute phase of the disease or during those going through chronicity with slow and progressive deterioration;27 this is true not only for patients but also for their caregivers. It seems that uncertainty has - at times - an immobilizing effect on anticipatory coping processes. Providing spiritual care can be seen as a mediator of the burden of caring; for caregivers of people with cancer, it focuses on the positive, self-satisfaction, and the sense of purpose in life, these results lead us to think on the need to continue inquiring further on the possibility spiritual support has on the better quality of life of caregivers and their sick relatives.

As can be seen, the caregivers in this study perceive as affected all the quality of life dimensions; this research seeks to contribute to understanding the caregivers of people with cancer and their impact on the quality of life of the caregivers. This can be the start of new studies regarding the problem. Preparing patients and families facing this disease should be considered a critical element for healthcare teams in oncology units; the interventions we must undertake as nursing professionals point in important manner to the comprehensive support provided and to the conformation of support groups.

REFERENCES

1. Ochoa FL, Montoya LP. Carga de cáncer en Colombia. Rev Col Cancerol. 2007; 11(3):168-73. [ Links ]

2. Cornelius FH. Enfermería oncológica: atención domiciliaria, entornos alternativos para la atención y recursos para el tratamiento del cáncer. 3 ed. Barcelona: Harcourt Brace; 2000. [ Links ]

3. Krouse R, Grant M, Ferrell B, Dean G, Nelson R, Chu D. Quality of life outcomes in 599 cancer and Non-Cancer patients with colostomies. J Surg Res. 2007; 138(1):79-87. [ Links ]

4. Giraldo CI, Franco GM. Calidad de vida de los cuidadores familiares. Aquichan 2006 ;6(1):38-53. [ Links ]

5. Organización Mundial de la Salud. Programa de envejecimiento y ciclo vital. Envejecimiento activo: Un marco político. Rev Esp Geriatr Gerontol. 2002; 37(S2):74-105. [ Links ]

6. álvarez B. Comparación de la calidad de vida de cuidadores familiares de personas que viven con VIH/Sida y reciben tratamiento antirretroviral con la calidad de vida de cuidadores familiares de personas que viven con VIH/Sida y no reciben tratamiento antirretroviral de Honduras. Av Enferm. 2004; 22(2):6-18. [ Links ]

7. Cardona D, Agudelo B. La flor de la vida: pensemos en el adulto. Aspectos de la calidad de vida de la población adulta. Medellín: Universidad de Antioquia; 2006. [ Links ]

8. Ferrel B, Ervin K, Smith S, Marek T, Melancon C. Family perspectives of ovarian cancer. Cancer Pract. 2002; 10(6): 269-76. [ Links ]

9. Pinto N. La cronicidad y el cuidado familiar, un problema de todas las edades: los cuidadores de adultos. Av Enferm 2004; 22(1):54-60. [ Links ]

10. Montalvo A, Romero E, Flórez IE. Percepción de la calidad de vida de cuidadores de niños con cardiopatía congénita. Cartagena, Colombia. Invest Educ Enferm. 2011; 29(1):9-18. [ Links ]

11. González DS. Habilidad de cuidado de los cuidadores familiares de personas en situación de enfermedad crónica por Diabetes Mellitus. Av Enferm. 2005; 24(2):20-37. [ Links ]

12. Gálviz CR, Pinzón ML, Romero E. Comparación entre la habilidad de cuidado de cuidadores de personas en situación de enfermedad crónica en Villavicencio, Meta. Av Enferm. 2004; 22(1):4-26. [ Links ]

13. Ubiergo MC, Plegoyos S, Vicon MV, Reyes R. El soporte de enfermería y la claudicación del cuidador informal. Enferm clín. 2005; 15(4):199-205. [ Links ]

14. Merino SE. Calidad de vida de los cuidadores familiares que cuidan niños en situaciones de enfermedad crónica. Av Enferm. 2004; 22(1): 39-46. [ Links ]

15. Deví J, Almazán I. Impacto emocional y cambios familiares en la demencia. Geriátrika. 2002; 18(5):43-7. [ Links ]

16. Barrera L. Carrillo GM, ChaparroL, Pinto N, RodríguezA, Sánchez B. Effect of the Program ''Caring for caretakers'': Findings of a multicenter study. Colom Med. 2011; 42(2):33-44. [ Links ]

17. Parra D. Contribución de las mujeres y los hogares más pobres a la producción de cuidados de salud informales. Gac Sanit. 2001; 15(6):498-505. [ Links ]

18 . Pinto N, Barrera L, Sánchez B. Reflexiones sobre el cuidado a partir del programa Cuidando a los cuidadores. Aquichan. 2005;5(1): 128-37. [ Links ]

19. Venegas BC. Habilidad del cuidador y funcionalidad de la persona cuidada. Aquichan. 2006; 6 (1): 137-47. [ Links ]

20. Barrera L, Galvis CR, Moreno ME, Pinto N, Pinzón ML, Romero E. La habilidad de cuidado de los cuidadores familiares de personas con Enfermedad Crónica. Invest Educ Enferm. 2006; 24(1):36-46. [ Links ]

21. Rivera A, Montero M. Espiritualidad y religiosidad en adultos mayores Mexicanos. Salud Ment. 2005; 28(6):51-58. [ Links ]

22. Whetsell M, Frederickson K, Aguilera P, Maya JL. Niveles de bienestar espiritual y de fortaleza relacionados con la salud del adulto mayor. Aquichan. 2005; 5(1):72-85. [ Links ]

23. Sánchez B. La experiencia de ser cuidadora de una persona en situación de enfermedad crónica. Invest Educ Enferm. 2001; 19(2):36-49. [ Links ]

24. De la Cuesta C. Cuidado familiar en condiciones crónicas: una aproximación a la literatura. Texto Contexto Enferm. 2004; 13(1):137-46. [ Links ]

25. Vega OM, Mendoza M, Ureña MP, Villamil WA. Efecto de un programa educativo en la habilidad de cuidado de los cuidadores familiares de personas en situación crónica de enfermedad. Rev Cienc Cuidado. 2008; 5(1):5-19 [ Links ]

26. Sánchez Herrera B. Dimensión espiritual del cuidado en situaciones de cronicidad y muerte. Aquichan. 2004; 4(4):6-9. [ Links ]

27. Treviño V, Zaider G, Sanhueza. Teorías y modelos relacionados con la calidad de vida en cáncer y enfermería. Aquichan. 2005; 5(1):20-31. [ Links ]