Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Investigación y Educación en Enfermería

Print version ISSN 0120-5307

Invest. educ. enferm vol.31 no.3 Medellín Sept./Dec. 2013

LEARNING EXPERIENCE/ EXPERIENCIA EDUCATIVA/ EXPERIÊNCIA EDUCATIVA

Reorganization of elderly care in a primary health care service through the Altadir method of popular planning

Reorganización de la atención a las personas mayores en un servicio de atención básica de salud utilizando el método Altadir de planificación popular

Reorganização do atendimento ao idoso no serviço de atenção básica de saúde através do método Altadir de Planejamento Popular

Hellen Pollyanna Mantelo Cecilio1; Simone de Araújo Lopes2; Vanessa Denardi Antoniassi Baldissera3; Lígia Carreira4

1RN, Master candidate. Universidade Estadual de Maringá UEM, Paraná, Brazil. email: pollymantelo@gmail.com.

2RN, Resident Universidade Estadual de Londrina, Paraná, Brazil. email: si_lopes@yahoo.com.br.

3RN, Ph.D. Professor UEM, Paraná, Brazil. email: vanessadenardi@hotmail.com.

4RN, Ph.D. Professor UEM, Paraná, Brazil. email: ligiacarreira@hotmail.com.

Receipt date: Jul 12, 2012. Approval date: May 8, 2013

How to cite this article: Cecilio HPM, Lopes AS, Baldissera VDA, Carreira L. Reorganization of elderly care in a primary health care service through the Altadir method of popular planning. Invest Educ Enferm. 2013;31(3): 480-486.

ABSTRACT

This paper's objective was to describe the experience of students and professors in selecting problems and developing strategies to solve these problems using the Altadir method of popular planning during the undergraduate nursing program at the State University of Maringá, Paraná (Brazil). The problem selected was care provided to elderly patients in a primary health care service. This paper provides a reflection on the use of the Altadir method to improve the quality of care delivered to this population.

Key words: aged; aged rights; health public policy.

RESUMEN

Este artículo tuvo como objetivo describir la experiencia de los estudiantes y profesores en la selección de problemas y elaboración de estrategias para su solución mediante la utilización del método Altadir de planificación popular durante el desarrollo del curso de graduación en Enfermería de la Universidad Estatal de Maringá, Paraná (Brasil). El problema seleccionado fue la atención que recibían las personas mayores en un servicio de atención básica de salud. Se reflexiona sobre la utilidad del empleo del método Altadir para el mejoramiento de la calidad de la atención de este grupo poblacional.

Palabras clave: anciano; derechos de los ancianos; políticas públicas de salud.

RESUMO

Este artigo teve como objetivo descrever a experiência dos estudantes e professores na seleção de problemas e elaboração de estratégias para sua solução mediante a utilização do método Altadir de planejamento popular durante o desenvolvimento do curso de graduação em Enfermaria da Universidade Estatal de Maringá, Paraná (Brasil). O problema selecionado foi o atendimento que recebiam as pessoas maiores num serviço de atendimento básico de saúde. Reflexiona-se sobre a utilidade do emprego do método Altadir para o melhoramento da qualidade do atendimento deste grupo populacional.

Palavras chaves: idoso; direitos dos idosos; políticas públicas de saúde.

INTRODUCTION

The Brazilian Unified Health System (SUS), created by the Constitution of 1988, ensures that Brazilian citizens have equal access to health services. The SUS adopted the Family Health Strategy (FHS) in 1994 to reorganize Primary Health Care (PHC) in order to promote health and prevent diseases in the community through coordinated work within the health network, valuing life and quality of life.1 Guaranteeing health implies citizens have universal and equal access to health services in combination with social and economic policies designed to reduce inequalities and enable special care to vulnerable groups, especially the poor, the elderly, women and those living in rural areas.

In 2009, the Brazilian population 60 years old or older totaled approximately 21 million people.2 The repercussions of the profound social transformations accruing from the aging process are seldom addressed and is especially the role of the health sector, to reflect upon the cultural and social changes resulting from this growth. Expenditures on health are progressively greater with the aging population, though large expenditures do not necessarily ensure improved quality of life for the elderly. The determinants of health over the course of life for this population's have to be taken into account so that the policy for the elderly is effective.3

Discussions on this subject are needed so that the reality in which health care is provided to the elderly population is brought to light in order to implement public health policies coherent with this population and improve the quality of care delivered to them. There is an urgent need to reorient care delivered to the elderly, especially within the PHC, ensuring that the work process of the family health teams is characterized by the development of actions that embrace elderly individuals. Health professionals should understand the specificities of this population and the current Brazilian legislation and work to ease access of elderly individuals to the most diverse levels of complexity of health care.4

Through Law 8 842, January 4th 1994, the Federal government defined and consolidated the National Elderly Policy, the purpose of which is to create conditions to promote longevity characterized by a high quality of life, not only for the current contingent of elderly individuals but also for those aging in the future. This initiative, however, ran afoul of a structural deficit of the health system, which hindered the exercise of rights ensured by law.5 The Elderly Statute, which entered into force in 2003 was an important advancement in Brazilian legislation. It was developed with an intense participation of agencies defending the interests of the elderly and greatly expanded the response of the State and society to their needs. It deals with the most varied aspects, ranging from fundamental rights to the establishment of punishment for the most common crimes perpetrated against these people.6

Law No. 10 741 from October 1st 2003, which mandates on the Elderly Statute reports, states in its Sole Paragraph the guarantee of priority that confers immediate preferential and individualized service to the elderly by both public and private service providers.7 Therefore, the PHC unit, which is the portal to the health care system, should ensure priority of care to the elderly population. This study was conducted in the context of the FHS and discussions about PHC and portrays the development of planning in a PHC unit in Maringá, PR, Brazil. Hence, its objective was to report the experience of using the Altadir Method of Popular Planning in the reorganization of access for the elderly into a health service.

METHODOLOGICAL APPROACH

This experience report focuses on the use of the Altadir Method of Popular Planning (AMPP), which is based on the principles of Situational Strategic Planning. Health planning, as a managerial tool, is important for putting the organizational mission into effect, imposing rationality and a direction on the services' organization and establishing coordination and integration among the different work units.8 The planning method used in this case has operational features at the local level aiming to enable planning founded on the characteristics of a popular base. This favors the community's involvement in and commitment to coping with problems and is coherent with the principles of the SUS, thus, the method is recommended as a instrument to develop planning in PHC units.9 For that, the participation and collaboration of the health staff, composed of the unit's board of directors, nurses, nursing auxiliaries and technicians, was essential, in addition to the central support of the health community agents and the unit's front desk personnel. The AAMP refers to an action plan developed as part of the Interdisciplinary Supervised Training in the last year of the nursing undergraduate program at the State University of Maringá, enabling students to be included in the managerial processes of the PHC service through this feasible instrument of planning: the AMPP.

Therefore, planning followed the steps:10 Stage 1. Survey of problems: Step 1) Selection of problems: a preliminary list was prepared and then a discussion was conducted with the health staff to verify the validity of problems identified by the students. According to the purpose of the supervised training, students had to choose a problem that was possible to solve within the training's short time of duration. Stage 2. Selection of the problem and development of explanations: Step 2) Description of the problem: this stage is not to be confused with the causes or consequences. For that, students should elect a set of descriptors, which are facts or statements necessary and sufficient to describe the problem; Step 3) Explanation of the Problem - Explanatory three: in this phase, indicators that show the problem's level of severity are taken into account, as well as the problem's cause and effect relationship; Step 4) Formulation of situation-objective: a discussion of the objectives that can be achieved and how to make them viable. It is necessary to assess how long it will take for the plan to mature and identify the operations that can produce the desired change; Step 5) Selection of multi-pronged attack: defined through a dialog with the staff on potential causes of the problem, its impact, possibilities of action and consequent selection of each of the causes for later design of operations; Stage 3. Proposal of intervention: 6) Design of operations and demands: operations were elected for each cause selected in the previous step assigning those responsible and those who play a role in support; 7) Assigning those responsible for the operations; 8) Assigning those responsible for the operations' demands; 9) Assessment and calculation of the resources necessary to develop operations; 10) Identification of the relevant social actors and their motivations in relation to the work plan; 11) Identification of the resources critical to develop operations; 12) Identification of those controlling the resources; 13) Selection of trajectories; 14) Analysis of the plan's vulnerability; and finally 15) Design of accountability within the system .

These steps were performed from March to May 2010 in a PHC unit in the North of Maringá, PR, Brazil, which corresponds to the training's period of duration, which was divided into three sequential stages: survey of problems; selection of problem and development of explanations; and finally, proposal of intervention.

The PHC unit, which is the setting of this study, has in its coverage area a population of 10,400 inhabitants who are registered with/monitored by the Family Health Strategy. Most of this population uses the SUS to access health services. According to data in the PHC Information System (SIAB), only 1,045 people have a private health plan, which corresponds to 10.05% of the population, hence 89.95% use the SUS.

The experience: reorganization of the access of elderly individuals to the health service using the Altadir method of popular planning

The first stage of the Interdisciplinary supervised training took approximately ten days and included observation of the activities performed in the Family Health Unit, which enabled the identification of problems that hindered the staff's work. For that, the nursing students participated in the routine activities of the Family Health teams. In this first stage, they developed step 1 of the AMPP, which refers to the selection of problems, including a discussion with the health staff, through which the validity of the identified problems in terms of the value assigned to each of them was verified.

Among the diverse needs reported by the staff, the following were highlighted: a high rate of pregnancies during adolescence and delayed prenatal care; difficulty providing care to and treatment adherence on the part of previously institutionalized mental disorder patients being monitored in the FHS; low coverage of childcare and a high number of infants at risk; high rate of smoking and a lack of healthy habits among the male population; lack of physical structure for some activities, such as staff meetings; insufficient human resources to meet the unit's large demand; isolation and sedentary status of the elderly population; lack of priority in the care provided to the population that is 60 years old or older.

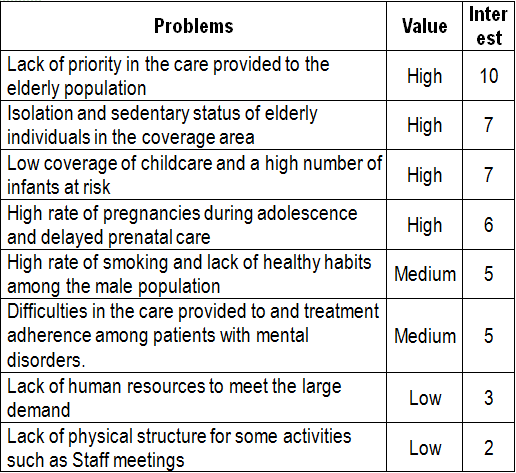

First, to develop an action plan that solved one of the various problems, students needed to choose one problem that would be possible to solve within the short time available and, at the same time, was feasible within the existing routine given the insufficient human resources. Hence, after discussions among the students, professors, FHS staff, employees and patients of the PHC unit, we opted to implement priority care to the elderly individuals. This priority was one of the unit's management goals and was the one with the greatest acceptance among the employees. The problems were organized on a list where value and interest was assigned to each, which permitted a better visualization of the problem selected (Table 1).

Table 1. List of problems, value and interest assigned by those involved

We based our work on the premise that the creation of laws to ensure rights always results in benefit to society; a law is an advance because the law is an instrument to validate claims. The Elderly Statute presents a fertile and stimulating field for society to mobilize and demand that laws that benefit the elderly are enforced. With this in mind, we proposed to address one of the rights provided in the Elderly Statute, which is priority care in the PHC unit. We understand that the reorganization of the process of receiving elderly individuals into health units is one of the strategies for coping with current access difficulties. Given this statement, we considered the lack of credibility of priority access of elderly individuals in health services, showing that the organizational process of PHC units is still deficient, hindering the concretization of public policies,11 as is the case in the care provided to the elderly. Despite the Elderly National Health Policy created in 1994 and the Elderly Statute in 2003, only in 2006, through the Pact for Health, did the SUS start to consider the health of the elderly population to be a priority.5

This priority results from an understanding that the aging process, being an inexorable process for living beings, leads to a progressive loss of the body's functional abilities with repercussions for one's health and life. It is argued, therefore, that changes inherent to the aging process take place in the biopsychosocial dimension and impose risks on the elderly individual's quality of life, whether because they limit one's ability to vigorously perform daily life activities with strength, or because the individual becomes vulnerable.12

In this sense, elderly individuals affected by impairing chronic diseases need support from the various organizations in a social support network, such as health services, to remain in their family and social environments.13 Based on this, we can state that aging is a social concern and has become a public health problem of great magnitude and transcendence.14

The growth of the elderly population shows that aging is permeated by a dialogical situation of losses and gains, and it is desirable to acknowledge intangible and untouchable rights concerning elderly care based on four essential points: fair treatment through acknowledging their rights; right to equality through processes that fight discrimination; right to autonomy with social and family participation; right to dignity, respecting their image and ensuring, in its multiple aspects, satisfaction with life in old age.14 For that, society needs to become aware of these needs and the competent authorities need to find fair and democratic ways that lead to the equitable distribution of services and facilities for this population.

Steps 2 to 5 of the AMPP were performed in the training's second stage. In relation to the description of the problem, we based it on the need to comply with Law 10,741, that concerning the priority of service to elderly individuals on the part of public and private service providers, as is the case of the PHC unit, and which has a political and social value for this population. A survey conducted in the PHC Information System, SIAB, revealed that 756 men and women 60 years old and older, representing 7.27% of the total population in the unit's coverage area, fully use its services and in a higher proportion than the remaining population. Therefore, the problem's descriptor was: Absence of priority service to the elderly in the primary health care unit; the indicator was: Constant presence of elderly individuals in the waiting lines for procedures and care actions in the primary health care, in disregard of the law.

In this stage, it is essential to identify the causes and consequences of the Absence of priority care to elderly individuals cared for in the primary health care unit in order to devise strategies for intervention: a) Causes: Lack of a method to determine priority in care delivery and organization of the demand for elderly care and lack of knowledge, on both the part of the users and service, concerning the relevant legislation; b) Consequences: violation of the law; elderly individuals spend more time waiting in lines, which affects the care delivered to elderly individuals.

Considering that most elderly individuals have at least one chronic disease and approximately 10% present at least five of these diseases15, an expressive demand for health services is expected. In this sense, there is an urgent need for technicians and professionals providing care to this population, especially those in the health field, to discuss and disseminate the rights of the elderly in all social spheres.5

The right established by the State, however, is not sufficient to define the enforcement of rights or to ensure citizens will have their rights enforced, because there is a certain correlation of socioeconomic forces. For this reason, establishing rights can mean changing the crystallization of power16, which however, requires strategies for its implementation.

We determined, through dialoguing with the team, that this strategy to change care would first be implemented with medical consultations that were already scheduled, regardless of the patients' place in line, laboratory exams, nursing consultations, how patients are received into care, bandages, and other procedures. This priority care could be later extended to other areas.

Steps 6 to 15 of the AMPP were developed in the training's third stage. The operations were based on discussions with the nursing staff, community health agents, the unit's board of directors, employees and front desk personnel, when their opinions concerning the possibility of implementing these strategies were heard. This step represented social participation and the decentralization of actions in the PHC unit, since the different actors in the health unit participated in the planning of actions, providing their own views. The AMPP also strengthened the commitment of these social actors with the objective of action, since these decisions were shared with the whole team.

The students designed and fashioned cards to identify the medical files of the elderly individuals waiting for appointments. Additionally, an explicative folder concerning the law was handed to those visiting the unit and also during home visits while posters were hung in the unit. People received clarification about Law 10,741/03 and about changes in the care provided to the unit's population. As a result of this method of local planning, we verified, at the end of the interdisciplinary supervised training, that since health education for the elderly is relatively recent, some health professionals experienced difficulties directing care and identifying what issues, easily modifiable, can favor care delivered to this population. Hence, actions directed to the health of elderly individuals in the FHS are in the process of being constructed. The work, however, has already shown satisfactory results, such as the sensitization of professionals and other patients attending the PHC unit concerning the priority care provided to elderly individuals with consequent improvement in the quality of services and reduced waiting time, in addition to the dissemination of knowledge concerning elderly rights.

Final Considerations. The spread of the aging phenomenon brings with it the need to analyze and communicate its impact on and implications for public policies, as well as in regard to care provided to this population in an attempt to encourage the services to adopt measures to cope with this reality. Among these measures, two had special prominence in the health field: promoting healthy aging and fighting for aging with rights and dignity. The strategy enabled the decentralization of decisions, which resulted in greater participation of those involved, strengthening their motivation and commitment to the implemented actions. It was a very rich experience at the completion of the nursing undergraduate program, since it sought to reinvigorate multidisciplinary teamwork to ultimately reflect on the routine of care service in order to change reality.

REFERENCES

1. Ermel RC, Fracolli LA. O trabalho das enfermeiras no Programa de Saúde da Família em Marília/SP. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2006; 40(4):533-9. [ Links ]

2. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Síntese de Indicadores Sociais: Uma Análise das Condições de Vida da População Brasileira 2009. Brasília (DF): Ministério do Planejamento, Orçamento e Gestão; 2009. [ Links ]

3. Veras R. Envelhecimento populacional contemporâneo: demandas, desafios e inovações. Rev Saúde Pública. 2009; 43(3):548-54. [ Links ]

4. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde (BR), Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde, Departamento de Atenção Básica. Envelhecimento e saúde da pessoa idosa. Brasília (DF): MS; 2006. [ Links ]

5. Rodrigues RAP, Kusumota L, Marques S, Fabricio SCC, Rosset-Cruz I, Lange C. Política nacional de atenção ao idoso e a contribuição da enfermagem. Texto Contexto Enferm, Florianópolis. 2007; 16(3):536-45. [ Links ]

6. Saliba O, Garbin CAS, Garbin AJI, Dossi AP. Responsabilidade do profissional de saúde sobre a notificação de casos de violência doméstica. Rev Saúde Pública. 2007; 41(3):472-7. [ Links ]

7. Brasil. Lei n. 10.741. Dispõe sobre o Estatuto do Idoso e dá outras providências. Diário Oficial da Republica Federativa do Brasil, Poder Executivo, Brasília (DF); Oct 1, 2003. [ Links ]

8. Kurcgant P, Ciampone MHT, Melleiro MM. O planejamento nas organizações de saúde: análise da visão sistêmica. Rev Gaucha Enferm. 2006; 27(3):351-5. [ Links ]

9. Slalinski LM, Scochi MJ, Mathias TAF. A Utilização do Método Altadir de Planejamento Popular durante estágio curricular. Ciênc Cuid Saúde. 2006; 5(1):75-81. [ Links ]

10. Tancredi FB, Barrios SRL, Ferreira JHG. Planejamento em Saúde. Série Saúde e Cidadania. São Paulo: Faculdade de Saúde Pública da Universidade de São Paulo; 1998. [ Links ]

11. Botti ML, Scochi MJ. O Aprender Organizacional: relato de experiência em uma unidade básica de saúde. Saúde Soc. 2006; 15(1): 107-14. [ Links ]

12. Pereira RJ, Cotta RMM, Franceschini SCC, Ribeiro RCL, Sampaio RF, Priore SE, et al. Contribuição dos domínios físico, social, psicológico e ambiental para a qualidade de vida global de idosos. Rev psiquiatr Rio Gd Sul. 2006; 28(1):176-83. [ Links ]

13. Nardi EFR, Oliveira MLF. Conhecendo o apoio social ao cuidador familiar do idoso dependente. Rev Gaúcha Enferm. 2008; 29(1):47-53. [ Links ]

14. Santos SSC. Concepções teórico-filosóficas sobre envelhecimento, velhice, idoso e enfermagem gerontogeriátrica. Rev Bras Enferm. 2010; 63(6):1035-9. [ Links ]

15. Organização Mundial de Saúde. Cuidados Inovadores para Condições Crônicas: componentes estruturais de ação. Relatório Mundial. Brasília: Organização Mundial de Saúde; 2003. [ Links ]

16. Faleiros VP. Cidadania e direitos da pessoa idosa. Ser social. Brasília. 2007; (20): 35-61. [ Links ]

text in

text in