Introduction

Care may be defined as the process of ensuring that the necessities of life are met. It is probably one of the most important human functions. The context of care in the family in Western societies currently rests on three inter-related pillars: 1) Ageing, which goes together with an increase in dependence,1 and in chronic and degenerative diseases;2 2) Care as a women’s issue which causes social and health inequalities,3,4 and has been called into question by women’s roles having changed more than men’s (the incorporation of women into the workforce, not to the same extent as men are incorporated into the domestic world),5 as well as changes in the family and ways of living together;6 And 3) the complex and current phenomenon of immigration and the pressure it places on job availability in general and for women in particular. Here, the possibilities for vulnerability or exclusion are threefold, namely, being female, coming from a different ethnic group, and being located in the lowest segments of society.7

New care strategies are arising spontaneously from all of the above. These include outsourcing some domestic tasks and care for dependent persons, carried out largely by low-paid immigrant women.8 Domestic Care clearly shows the internationalization of the sexual division of labor, because the tasks of home care are transferred to a third person, another woman. Native women don’t share with their partners but hire immigrant women to look after their elders. These, in turn, allow other women to care for their families at home, becoming global care chains.9 These informal care practices of women in hiring and employing immigrants contribute in changing history, forcing changes in family dynamics in both societies of origin and reception, because women are incorporated into the labor market, externalizing the domestic work/care. This draws a new phenomenon of transnational family and linking people around the world.

Risk groups related to family care: Women with difficulties in making effective their emancipation, older people with few resources and poor care, and female migrant domestic workers who are invisible and voiceless.5 In light of this situation, many questions must be answered: about the impact on care when two cultures combine; if our elderly are well cared for; how caregivers and dependent persons relate; whether the new situation creates problems of fairness within the families hiring workers, to name a few examples. Knowing the answer to these questions and understanding these family contexts, promote the essential progress and cultural competence of nursing professionals.8,10,11 Nurses, for its proximity to the population, are in a unique position to provide professional support in the family care.4 However, very few scientific studies have been done regarding this new and still unseen reality.5 The main purpose of this study is to identify and understand factors that influence the relationships in the environment of family care provided by live-in immigrant caregivers.

Specific objectives studied were as follows: to explore the conditions which lead to good or poor treatment in relationships; to explore the attitudes and characteristics of the immigrant caregivers, care receivers and their families which generate power relationships; to know the benefits, damages and difficulties for all of them.

Methods

In relation to the proposed objectives in mind, and considering the point of view of the true protagonists in the study situation to understand their experiences, opinions, expectations, perceptions and feelings, a qualitative methodology was used, and an interpretive study was done from a phenomenological perspective. The study was carried out within the province of Seville (Spain), between June 2008 and July 2015 on families with elderly dependents with a live-in female immigrant caregiver. The inter-relation of the analysis units of health, dependency and care were studied, in addition to the three irreducible components of personal identity5gender, ethnicity and social class.

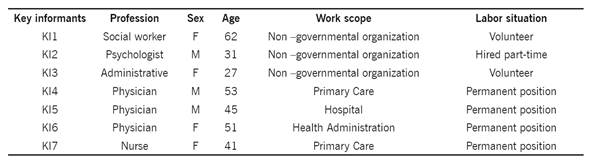

The researchers held several planning meetings to establish strategies for obtaining the information (literature review, in-depth interviews, discussion groups and participant observation), selection criteria and design of interview guides, group discussions and participant observation. Initially a thorough literature review and databases was done, which allowed us to identify the social sanitary, cultural and political context of family care and immigrant women. The first phase of the fieldwork (June/July 2008) involved seven in-depth interviews with key informants: three members of NGOs, a primary care physician, a primary care nurse, a hospital physician and a doctor working in health administration. These interviews allowed nuance the design of the guides, interviews profiles and composition of the discussion groups.

For performing in-depth interviews with the true protagonists of the study: the immigrant caregivers, care receivers and their families, a theoretical or deliberate sample was selected by searching for cases with a certain pattern. To that end, segmentation criteria were selected (sex, citizenship status, native country of caregivers and socioeconomical level for care receivers and family members) which determined the basic profiles of the people being interviewed (no male immigrant live-in caregivers were found). Within these profiles, other variables were chosen because of their importance in representing the interviewees. These profiles were provided to community nurses from different health centers in Seville who contacted several people in their population who wanted to participate in in-depth interviews and made appointments with the researchers. Two interviews were performed for each profile, making a total of 18, during 2009. Researchers, as active members, included participant observation in their home visits, accompanying community nurses who facilitated contact: nine families were observed (two researchers per family) for two years (2010 and 2011). Systematic, detailed observations of behaviour and conversations were made by observing and recording what people said and did in their natural environment. The information was gathered in a non-intrusive way in an attempt to portray their social and cultural reality.

Finally, two discussion groups were created in March 2010 as a qualitative technique for identifying shared or common knowledge among those groups of healthcare practitioners most involved in caring for dependents and immigrants: nurses and social workers, aspiring to reproduce their daily or basic ideological discourse on this reality. Originally, another discussion group for doctors had been created, but after interviewing key informants from that profession, they said they were not the people closest to this reality. However, we did gather considerable information by interviewing doctors at different levels of the Public Health System. Being a nurse or a social worker was established as homogeneity criterion to maintain group symmetry and take advantage of common experiences, and as heterogeneity criteria so that excessive homogeneity did not inhibit the group and to ensure the confrontation from different perspectives: sex, work scope, years working, the geographic area in Seville (different population). Finally two discussion groups were established, with ten nurses and six social workers, selected and contacted by telephone by the researchers. In 2015 another group of immigrant caregivers was conducted to compare the results obtained in previous years.

Interviews with key informants were performed in cafés, their workplaces or the University of Seville campus. The others in-depth interviews were carried out in places more comfortable for interviewees: most taking place at the homes where they provided the care, due to the situation and the conditions of the work itself. The discussion groups met at the university. All interviews lasted approximately one hour in a cordial atmosphere, ensuring maximum privacy and confidentiality. At the beginning of each interview, following personal introductions, the purpose of the study, what the information would be used for and that it would be anonymous were all explained. After receiving the consent of the interviewees, the information obtained was recorded and transcribed word-for-word. Saturation level was reached.

Guides qualitative techniques were as follows:

In-depth interview key informants and discussion groups health professionals: a- Health status of the immigrant population; Disease, old and new alterations; Needs and risk factors; Felt morbidity, disability and mortality; Prioritization problems; Beliefs, attitudes and imaginary against health and disease; Coping strategies. b- Living and health: Family situation; Legal status; Migration project. c- Working conditions and health: Relationship between the immigrant caregiver, the elderly person and his/her family (Power/egalitarian; Positive and negative factors); How influences the life and health care work in immigrant caregivers (benefits, damages and difficulties); How influences this care in the life and health of care receivers and their families (benefits, damages and difficulties); Previous experience and training of immigrant women caregivers in care for the elderly or sick people; Care strategies used by immigrant families and caregivers.

Participant observation: a- Relationship between people: Treatment (affectionate, derogatory, indifference); Physical contact; Glances; Verbal contact (Tone, Expressions, How are directed between them; If they call them by name); Respect or relationship of power / submission; Tense or relaxed: laughter, silences ... b- Mutual satisfaction: What do they tell each other? Is there praise? Is there reproach? c- Body position: relaxed, fear, self-conscious.

In-depth interview and discussion group immigrant caregivers: a- Basic data and information: name, native country, age, time in Spain, reason for immigration: to Spain, to Andalucia, educational level, profession, religious beliefs. b- Life conditions: Family in Spain (single, who lives now, support in Spain); Legal situation; Migration project. c- Working conditions and health: Difficulties finding work in Spain; About work (if this is her first job in Spain; Other jobs; Type of work (tasks, timetable, wages and guarantees, rest); Labor contract; Social Security; Length of time on it; Difficulties and possibilities, advantages and disadvantages (Cultural differences that interfere with work; Motivations for caring; Relationship with the elderly person and his/her family); Treatment, adaptation, acceptance, respect, exploitation (Possible prejudice for being immigrant, factors that have hindered the relationship: language, customs, treatment); Previous experience and training in care of elderly or sick people; Job satisfaction (Does she like it, is she happy, would she change jobs and why). Expectations; work influence in her life and health; What does it imply to care for a dependent during 24 hours; What she believes it means for the care recipient and family; Contributions, benefits of this work. d- Health status: Health problems (before / now) concerning immigration, new context, employment status. e) Social participation: Presence of relatives or friends in Seville; Communication and contact with family and / or friends in countries of origin; socio-cultural integration in Seville, Spain.

In-depth interview care receivers and families: a- Basic data and information: name, relationship with the care receiver, caregiver´s native country, age, educational level, profession, socioeconomical level. b- About the situation of care: How was the caregiver hired? Are the dependent´s needs covered? Why? Why not? (What do you expect from her? How do you believe it has benefited the care receiver and family; Relationship with them); Main difficulties or problems with the caregiver; Labor conditions (Tasks, timetable, wages and guarantees, rest, labor contract, time taken); If the caregiver knows what to do and how do you know what you want; Why an immigrant was hired? (If you are uncomfortable some attitude, her way of being, customs: what, why…; If you'd rather it was not an immigrant); If you have had more immigrants caregivers what do you think about them (What would you say are their best qualities?); Comments about immigration in Spain; Comments about the hired caregiver at home.

To safeguard the privacy of participants, their real names did not appear either in the transcripts or the results. The project was approved by the ethics committees of both University of Seville University and the Andalusian Health Service.

The QSR NUD*IST Vivo 9 software was used to analyse the qualitative data. Texts were classified by dimensions, properties and attributes: fragments of text were assigned to different categories by four researchers. Documents and categories were analyzed, crossed with each other and with the bibliography. Some analysis categories were established at the beginning and other were added as they arose (emerging categories). Categories were filtered and redefined through reading and discussing the text corpus.

This study involved a group of researchers that allowed a triangulation of both researchers and multidisciplinary visions (Nursing, Women and Gender Studies, Public Health, Cross-Cultural Care and Social and Cultural Anthropology), data sources (bibliographies, health practitioners, academics and volunteers, families caring for elderly dependents and female immigrant caregivers), and research techniques (in-depth interviews, discussion groups and participant observation). A feedback process was carried out with some participants in the study: a nurse, an immigrant paid caregiver and a family caregiver who also hired an immigrant for care. They scored a 1-5 Likkert scale of agreement or disagreement with the findings in the several categories.

Results

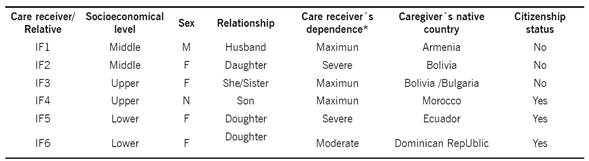

The description of key informants, caregivers and care receivers or their relatives can be seen in Tables 1, 2 and 3.

Table 2 In-depth interviews immigrant caregivers

* Acording to Barthel Index: independent, mild, moderate, severe, maximum

Table 3 In-depth interviews care receivers and families

* Acording to Barthel Index: independent, mild, moderate, severe, maximum

Have to start by knowing the economic, social and cultural reality of immigrant caregivers to understand the relationships that exist in the context of family care. The factors identified as cultural differences may favor good treatment or abuse depending on how the caregiver and care receiver understand them and act on it. In Table 4 these results are displayed, categorized and resources used to validate them. Attitudes and characteristics identified as generating power relations and, finally the benefits, losses and difficulties of this care for caregivers, care receivers and their families are also shown.

Table 4 Categories analysis and results

(*)Techniques triangulation: I (Interviews), DG (Discussion Groups), PO (Participation observation); (†) Feedback: P1 (Participant 1), P2 (Participant 2), P3 (Participant 3); IC: Interview caregiver; IF: Interview family; IKIC: Interview key informant; DGN: Discussion Group Nurses; DGSW: Discussion Group Social Workers; DGC: Discussion Group Caregivers

Discussion

An explanation and interpretation of the studied reality is proposed. It is presented as a result of the research based on given accounts (interviews and discussion groups), observation in different settings and bibliographic sources. This allows the triangulation between the different information sources, research techniques and researchers: all shown results coincide in the different techniques; in the discussion group of immigrant caregivers held in 2015 are confirmed.

Immigrant caregivers and their economic, social and cultural reality. Female immigrant caregivers endure very difficult situations. They believe that working as housemades, especially caring for elderly dependents, is the only way to enter the labor market and legalise their immigration status. This makes them withstand harsh situations. The legal regulation changed their lives. According to the organisation Colectivo IOÉ,12 paid care work offers a wealth of employment opportunities for the population of mostly female immigrants, almost always at low salaries. Our first results are in agreement with data of a spanish survey, which concludes that nearly 90% of the first job in Spain of immigrant women is live-in domestic one. Although they may find another job later.1 Actually, many female immigrant caregivers come from a higher socio-cultural level in their countries of origin (58% of those we interviewed). Currently, many women who emigrate by themselves are highly educated. According to Laura Oso,13 they accept a decrease in their social status because the economic gain or for the opportunity to develop their migratory project.

Cultural differences. We encountered different factors which may lead a cultural encounter or clash, depending on how they are dealt with. All of them are clearly determined by the type of relationship established between the care receiver and family, and the immigrant caregiver. The live-in situation has significant difficulties which are intensified by snobbery, xenophobia, prejudice and a lack of understanding or knowledge about the other person and his/her culture.14

Language. When the language is different, it creates a real communication barrier. When the language is the same (as with Latin American immigrants in Spain), difficulties are due to differences in certain words, nuances, idioms, and nonverbal communication. This makes comprehension difficult and sometimes leads to misunderstandings. As Clifford Geertz states,11 “culture is context, rather than text”. Among factors which may bring about discovery or confrontation depending on how they are handled, are communication difficulties, linguistic problems and cultural and emotional interferences.

Religion. Another component that enters into the equation is religion, a social issue present in all cultures because it is the product of the collective consciousness of transcendence and a person's relationship with the sacred, and it serves as a sign of identity for some societies.15) Religion may be respected, or judged and rejected, leading to a breakdown in the relationship. According to Fina Sanz,16 it is necessary to distinguish between profound knowledge (the universal search for the truth) and outward form (expression through different cultures: experiences, worship, rites, popular beliefs, etc.) which tend to cover up their deeper meaning. Converting religion into a component of culture shock means recognising only the outward form and passing judgment on different ways of living and the behaviours of different groups from an ethnocentric standpoint. When religious manifestations are respected, because people understand that beyond the outward forms, all people are equal and involved in the search for the same truth and transcendence in different ways, a door towards understanding is opened.

Food. This is the most commonly mentioned topic when exploring cultural differences. It is more pronounced when it does not create integration difficulties and foods are identified as markers of differences and identities. The most marked cases are seen with Muslims because of food-related religious precepts. Food is an excellent metaphor for human cultural identity, since it is oriented according to values.17 In this way, feeding behaviour is more greatly influenced by habits, customs and moral aspects than by logical reasoning.

The concept of space and time. A different concept of space and time is another factor which can generally cause disagreements. Ever since Durkheim18 established the social origin of time, we have understood that concept to be closely linked to social organisation, which is why it varies from one society to another. This difference in the perception of space and time, for example, the contrast between the obsessive attitude which industrial societies have with respect to time and the indifference shown by other groups, can sometimes lead to difficulties with the encounter, or be seen as a reason for preferring immigrants of certain nationalities depending on the task to be done, as we have shown in our study.

Use of names. The use of a personal name is a category which arose in this study when participant observation showed that some of the dependents did not refer to or call the caregiver by name, or they changed it to something more "familiar". A person’s name, understood as the manifestation of the “identity” which divides the concept of Self from the concept of others, expresses a socio-cultural fact which points to an ethnic or cultural affiliation.19 Eliminating or “adapting” a name, as we see in some of the families we surveyed, is another form of ethnic discrimination and cultural assimilation which promotes obscuring an identity; unconsciously, it signifies failure to recognise another person.

Relationships. The family’s social class and the caregiver’s attitude. Families of many different social backgrounds hire caregivers. The caregiver is so beneficial to the family that will make a financial effort or seek alternative strategies to be able to afford her. Our findings about the association between social class and types of relationships do not coincide with statements by some key informants who state that hiring a caregiver is only done by families of a higher social status. Marxist thinking has been so influential throughout history that when we speak of social class today, we only think of economic capital when we relate people with the means of production. However, the concept of “social classes” is complex because, according to Bourdieu's theory, different types of capital intersect: economic, cultural, social and symbolic.20 This complexity was taken into consideration when we interpreted our results: Economic capital has a smaller influence on the type of treatment and relationship than the cultural and educational level. A higher cultural level is generally linked to a less conservative ideology which favours an open attitude towards life, people and relationships.21 For that reason, well-educated and cultured families are more respectful of differences and more tolerant and likely to promote egalitarian relationships with the immigrant worker.

In this study, lower socioeconomic classes felt a closer link with the caregivers, empathised with them as workers, and generally established a respectful and egalitarian relationship with them. The fact that greater levels of intolerance and exploitation are to be found in the “nouveaux riche” families (higher socioeconomic class but lower cultural level) implies that they have used economic capital to gain symbolic power only. Their need to make their superiority known, and their treatment of those they hire reflects a power play with dominant and subordinate roles.

However, the adaptation process is bilateral; it depends not only on respect or lack of respect for differences on the part of the receiving society,20 but also on the immigrants’ attitudes of submission, servility, dignity and openness.

Benefits, damages and difficulties. If the relationship between the female immigrant caregiver, the elderly person, and his or her family is friendly, fair and equitable, all actors will obtain benefits: for the caregiver immigrant because it will foster their integration into the host society; for the older person because it will serve their needs, for the family because it will reduce the burden and create healthier family relationships. For female newcomers, the domestic care offers the unique opportunities for adaptation, integration, and personal enrichment (social and cultural capital). It provide a quick inclusion in the social fabric. They often work in neighborhoods with high rates of immigrant caregivers, forming neighborhood spaces that are ideal settings for regenerating their social capital and inclusion in the community.5 Domestic Care benefits the family, especially the women who are replaced because it reduces the burden of care. The recruitment of immigrant women allows the families to have healthier family relationships. Having the necessary trust to share the tasks of caring for a loved one promotes complicity in relationships.

On the other hand, caring for elderly dependents may affect the health of immigrant caregivers. Working as a live-in caregiver is both physically and emotionally demanding. They have to work long days, irregular hours and continuous shifts. The effects on the health of live-in immigrant caregivers may differ considerably depending on the person being cared for, his/her degree of dependence, the domestic tasks that have to be done, the relationship between caregivers and the dependent person and family,5 formation and their social support systems.22

With regard to the negative repercussions arising from the act of providing care itself, we must consider that providing care in a domestic setting makes workers invisible,4 and that there are no standards or recommendations to ensure their health in the workplace. The irregular and excessive demands23 which immigrant caregivers have reported to us in interviews, in addition to the dependence of the person being cared for, are negative factors which affect the quality of working conditions.24 All of this gives rise to different symptoms.5 They may suffer from the same symptoms and risks as caregivers within the family: sadness, apathy, tiredness, nervousness, irritability, breathlessness, muscle tension that causes headaches or lower back pain, etc.

An important factor which protects the health of everyone involved in the family care situation is the human relationship. All of the parts benefit from a warm, affectionate and communicative relationship. It is obvious that this would benefit the dependents receiving care in their houses, whose physical needs, generally speaking, are met satisfactorily, within the context of a relationship that is specific, separate from and beyond the connotations and contradictions normally present in family relationships. Not having family ties and establishing a new contract-based relationship free from past experiences and emotions makes the relationship more free from moral or emotional burdens. For the family, the option of hiring a caregiver, despite the inconvenience of the financial cost, brings worthwhile advantages.5 It provides them with respite from the physical, emotional and social overload of providing care, which they would experience without these women. And as with caregivers and care receivers, they too may benefit from an enriching relationship, on a physical, emotional and social level if it is egalitarian and positive.25

Strengths and Limitations. Although qualitative methodology chosen, it is often questioned because of the danger of excessive subjectivity, the rigorous description of the methodological process and the triangulation of researchers, information sources and information techniques, in addition to reaching the saturation level, save this question, as they provide reliability and validity, the study’s greatest strengths. The feedback process with some participants reinforce this rigor and validity. Carrying out interviews in family homes made it impossible to use a neutral setting, but the interviews would not have been possible in any other way. An important limitation has been the absence of male immigrant live-in caregivers, so it was not possible to compare caregivers by gender. We are unable to make conclusive statements regarding the relationship between social class and the type of relationship established. This is because it was not the main goal of this research project, and so we did not contemplate all of the possible profiles or reach saturation levels for this question; the approaches made will remain open for future investigations.

We have not found similar studies that have studied the relationships that occur in the context of family care by immigrants, and cultural factors that condition them; this has hindered the discussion of our results.

Implications. With this study, we have made it clear that this situation is not always undesirable. Rather, it can favour intercultural exchange and improve the health and care quality for the people involved. Our findings have been helpful in analysing the factors involved. This has led us to discard some of those myths appearing even in scientific journals, for example, that families with a high social class who hire female immigrant caregivers tend to exploit them more. Since this field work was carried out in the health care context, it was a source of information for many participating professionals, mainly nurses. They were introduced to assistance for immigrant caregivers in their daily routines and began to consider certain key aspects in this type of family-based care, advancing toward culturally competent care. This is essential for quality attention and care in current contexts. Our study will be helpful to the health system in its efforts to meet some of the needs of caregivers, care-receivers and families. It has also created possibilities to explore other lines of research arising from this study; to do a more in-depth study of the power relationships involved in family care, the various strategies for organising home care and the differences between care as provided by men and women.

Keeping in mind the threefold perspective of gender, ethnicity and social class in understanding the process being studied, we may draw the following conclusions:

Providing care is still a women´s matter, but we can observe changes, new strategies and alternative family and institutional measures for adapting to those changes and managing care, such as hiring immigrant women to carry out these tasks. In this way, we have shown that the sex-based division of labour has become international and formed global care chains, and demonstrated by caregivers and the families who hire them. This clearly shows the injustice of our society’s patriarchal base.

The care relationship established between immigrant caregivers, care receivers and their families is a privileged setting for intercultural discovery, the exchange of values and knowledge, and for acceptance and mutual respect, since it brings together the immigrant and national populations. However, since this work is carried out in a domestic setting, and is private and invisible, it runs the risk of leading to relationships based on domination and exploitation.

Certain factors are different or are viewed as such by different cultural groups. Depending on peoples’ attitudes, these may create difficulties in the relationship and lead to cultural clashes, or not imply insurmountable obstacles. These include verbal and nonverbal language, religion, food, respect for personal names, and the perception of space and time. The interpersonal relationship is the factor with the greatest effect on health and welfare. If the relationship is based on good and egalitarian behavior, it is a protective of all involved.

text in

text in