Introduction

Making the decision of becoming a mother can be made through a conscious and reflexive planning process 1) or through acceptance within a context of an unplanned or unwanted gestation;2 given that becoming a mother is one of the principal transitions in a woman’s life,3 which brings along the responsibility of caring for and maintaining life. One of the most recent theories that explain motherhood as a process is that proposed by Ramona Mercer, denominated “Becoming a Mother”.4 The author indicates that women transit through four stages: commitment, attachment and preparation, acquaintance, learning and physical restoration, moving toward a new normal and, finally, achievement of the maternal identity. In the first stage, women use two strategies: prepare and deal with reality, but no conceptual development is done on the meaning of preparing and no propositions are proposed between this and other concepts of the theory.5

Preparation for motherhood starts during the gestation period and this concept gains importance, given that in the experiences and perceptions of pregnant women, motherhood arrives without proper preparation;6 whether it is because of a gap between that informed and that experienced7 or because the information provided by the professionals does not comply with the real expectations of motherhood as a way of life and lifestyle.8 Although the literature review evidences a conceptual analysis of the preparation for motherhood,9 this extends to the first year of the child’s life, it only contemplates the preparation within the context of a wanted and planned gestation and in the presence of being in a relationship. These elements do not favor the application of the concept specifically in scenarios in which the pregnancy was unplanned or unwanted and in the absence of a significant companion.

Likewise, the scientific literature on the preparation for motherhood is quite limited to the gestation period,1,10 is inconclusive in the face of the constituent elements9, and much of it is oriented at the preparation for delivery11-14 and although the preparation can be understood as a continuum even after the gestation,10,15 the requisites, resources, and results can be different during this period.

Additionally, for many Latin American countries, prenatal care focuses specially on the physiological changes and management of morbid events, leaving aside the psychological and social changes experienced by women during gestation,16 ignoring that this stage represents a bigger challenge for the woman’s psychological and social function through development tasks that include, for example, relating the fetus as part of her and then seeing herself as a mother.17 Hence, it is indispensable to not only distinguish its use from scientific knowledge within the nursing discipline and specifically in the field of maternal-perinatal nursing, but also identifying those attributes that comprise the concept and which permit providing comprehension that facilitates development and validation of an instrument that has repercussions in the practice, reorientation of prenatal care, and prescription of nursing interventions that permit satisfying the needs and expectations of professional support the pregnant women require.18 The following presents the concept analysis of preparation for motherhood during gestation whose aim is to identify its attributes during this stage of the process.

Methodology

Concept analysis: used the methodology proposed by Walker and Avant,19 which examines the structure and function of the concept, besides defining its possibilities of use. A search was conducted for articles (original, reviews, editorials) in the scientific literature through Lilacs/BIREME, Pubmed/Medline, EMBASE, Science Direct, Ovid, EBSCO, CUIDEN, and Psychinfo databases, using as search strategy in Spanish ((“preparation” AND (“motherhood” OR “gestation”)), as words because these do not exist as MeSH terms and in English ((“preparation” OR “preparedness”) AND (“motherhood” OR “motherhood” OR “pregnancy”)), not as MeSH terms, except for “pregnancy”. In addition, the search criteria defined words in abstract/title, articles in Spanish, English, or Portuguese available in complete text. No year of publication limit was applied. A fundamental criterion was defined to include articles for the concept analysis whose theme of the preparation for motherhood during gestation had been central of the article, independent of the methodology used in the case of the original articles.

A manual search was also performed, which included textbooks on motherhood to identify if the concept of preparation appeared as constituent element of this process in the theoretical explanation offered by the authors. Furthermore, the work revised the bibliographies of the articles included to identify pertinent articles for analysis. Lastly, the study revised the definitions of the meaning of preparation in Spanish in the dictionaries from the Spanish Royal Academy and for English in the Oxford dictionary. A database was designed to consolidate the information from the articles and from other sources that included the following variables: title of the article or source, authors, year of publication, publication journal, volume and number in case of articles, editorial or web page; country of publication, type of article, results or principal discussions around the concept selected and step of the methodology of the concept analysis to which the results contributed.

Integration of the information from the literature review was accomplished through the steps proposed for the concept analysis by Walker and Avant:19 identify the uses of the concept, determine the attributes, identify model cases, limit and contrary, identify antecedents and consequences of the concept, and define the empirical references. Figure 1 shows the specific procedure in the collection of sources of information.

Results

Definitions and uses of the concept

Definitions from dictionaries

Preparation is defined as the action and effect of being prepared. It has it etymological origins in the Latin word praeparatio composed of the prefix prae that means before, the verb parare that means to do, make or leave ready, and the suffix tio that refers to the action and effect.20 The Oxford Living Dictionaries for Spanish21 defines that preparation is the disposition or arrangement of the necessary things to carry out something or for a given purpose. Likewise, it states that it may be understood as the set of teachings, advice, and practices with which one prepares another to achieve the physical or psychological conditions necessary to perform a future action or confront an unpleasant or negative situation.

Uses of the concept in literature

For Meleis,3 preparation and knowledge are facilitators of transitions. Anticipated preparation facilitates the transition experience, while the lack of preparation is an inhibitor. The author adds that knowledge is inherent to preparation. Lederman and Weis22 indicate that preparation is a component of identifying with a motherhood role. The authors argue that preparing for the new role occurs through two paths: fantasizing and dreaming. Fantasizing implies thinking about the characteristics desired as a mother and anticipating the life changes necessary in the future. Dreaming relates to reliving childhood, trusting maternal skills, and dreaming with the child’s health. Preparation through these two paths takes place by taking classes and pertinent reading material; it also implies confronting fears and anxieties, talking to other women, and observing how other women execute the tasks. For Pérez,23 preparation for a motherhood role implies active, positive, and conscious participation in the gestation, delivery, and puerperium processes to favor the relationships of the neonate and the family unit with repercussions on the newborn’s proper biological, psychological, and social development.

Preparation is one of the four steps for a motherhood role identified in the study by Underwood24 with Afro-American mothers. It indicates that preparation is learnt in the family of origin, it is a practice started during childhood through caring for siblings or younger relatives and is begun by the older female relatives. In their concept analysis on the preparation for a parenthood role, Spiteri et al.,9 do not define the concept, but propose that being fathers and mothers requires preparation from various perspectives. The state that preparation has always focused on labor and on delivery and propose that individuals can choose to make changes in their lifestyles and this includes changes to optimize their health, like eating healthy, doing exercise, and eliminating cigarette smoking and consumption of alcohol. In consonance, Smith25 established that the preparation for maternity during gestation is a symbiotic process that implies the woman’s intimate connection with significant others and facilitates the emergence of a new role as mother.

Riedmann1 describes the preparation for maternity as a process consisting of a series of steps that present unique challenges and dilemmas. These steps include the decision of becoming parents or discovering gestation within an unplanned scenario, elections related to the mode of delivery, the impact of the new maternity or paternity, and the issues of childcare that can be social, cultural, and spiritual. Likewise, Hernández26 proposes that gestation is a woman’s preparation process and that it is achieved through enlistment for birth and some appropriate eating practices. Mansfield27 discusses two important aspects required during the preparation for maternity: material and personal preparation. This involves the organization of oneself to become a person receptive to changes and being ready financially for this responsibility. Among the preparation material, consumption rituals, as exposed by Afflerback et al.,28 help the woman feel prepared, adding that preparation is for the child and that this includes patterns commonly shared and highly symbolic practices that involve consumption.

Related concepts

The concept most-often related to preparation for maternity has been that of preparation for delivery. For Lederman and Weis,22 preparation for delivery is a preparation for stress. It implies reaching an adequate mental and emotional state and a physical preparation through concrete actions and imaginary trials. For Tostes11 and Hollins,7 it is comparable to the preparation for maternity in the sense that the sensation of being prepared is insufficient. Additionally, it has been considered that the preparation for delivery implies identifying the institution for the delivery care,29 knowing the warning signs,10 saving some money, and preparing essential elements for the delivery.14

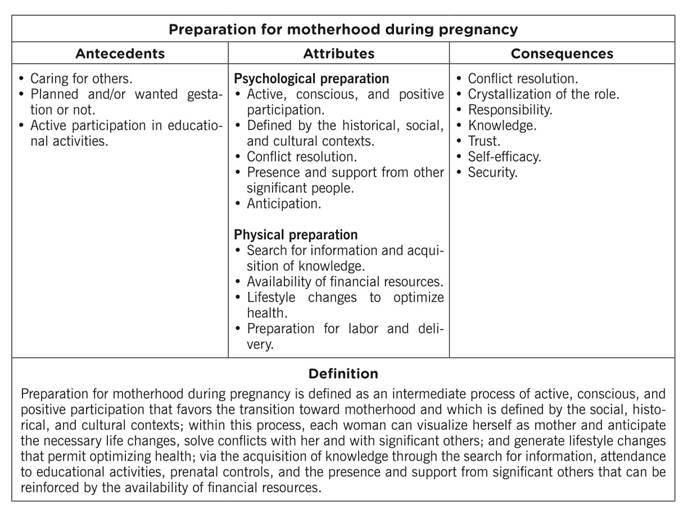

Antecedents of the concept of preparation for maternity during gestation

Preparation for maternity begins with the decision to become a pregnant woman or after discovering an unplanned or unwanted gestation for the moment. 1) Educational activities and prenatal controls also become an antecedent of the preparation for maternity. Although for some women these activities are not sufficient,8 others consider that prenatal classes prepared them well for labor, delivery, and some aspects of maternity,30 but not all, like - for example - caring for the newborn.(15,31) In spite of this situation, women in the study by Ho and Holroyd8 considered that the prenatal period is the ideal to get prepare on matters related to maternity. McVeigh30 proposes that anticipated preparation for maternity is required in its own social environment and that society needs to actively prepare its youth for one of the most demanding social roles, as shown by Thomas and Bhugra32 who identified that young people recognized a need to have programs for preparation for maternity to learn to solve problems on this issue before assuming their role as parents.

Consequences of the concept of preparation for maternity during gestation

Women who are well-prepared for maternity tend to have solved their conflicts regarding gestation and the imminent maternity and crystallize a new role for themselves that can be expressed as a need to bond to their child. 22) Further, George6 proposes that the lack of preparation can cause an overwhelming sense of responsibility, unclear expectations of the role, and deficit of knowledge. Women who are not prepared to go through maternity may have difficulties assuming the maternal role, besides feeling incapable of caring for the child, of not having the resources to offer proper care, or having the sensation of lack of experience in the role.33 Lack of preparation may also contribute to the emergence of depressive and anxious symptoms34 with what consequently could become post-partum depression. (35 ,36

Definition of the concept

Preparation for motherhood during pregnancy is defined as an intermediate process of active, conscious, and positive participation that favors the transition toward motherhood and that it is defined by the social, historical, and cultural contexts. In this process, each woman can visualize herself as a mother and anticipate the necessary life changes, solve conflicts with herself and with significant others, and generate lifestyle changes that permit optimizing health by acquiring knowledge through the search for information, attendance to educational activities, prenatal controls, and the presence and support from significant others that can be reinforced by the availability of financial resources.

Attributes of the concept

The following are considered the attributes that permit accounting for the concept of preparation for maternity during gestation:

Psychological preparation

It is an intermediate process of active and conscious participation.1,3,23,24,26,27

It is defined by the historical, social, and cultural contexts.9,22,30)

It is a stage that favors resolution of personal conflicts and conflicts with significant others.22,23,25

It is determined by the presence and support from other significant individuals.22,25,28

It is a period that anticipates the characteristics desired as a mother and the necessary life changes for it.22

Physical preparation

Implies the search for information about gestation, delivery, caring for and upbringing the child.(3,22-24)

Demand availability of resources, among them, financial.(9,27,28)

Requires lifestyle changes to optimize health.(9,26)

Reinforced with attendance to educational activities and to prenatal controls.(8,15,30-32)

Includes preparation for labor and delivery.(22,26)

The following describe the model, limit, and contrary cases from the personal and professional experience in caring for pregnant women. The names were changed to protect the identity of the cases.

Model case

Carol is a 25-year-old woman, living in common-law manner with her partner and not long ago discovered she was pregnant; although she had not planned it, being a mother was part of her life project. Ever since she found out, she began changing her eating practices and started to exercise three times per week. She began her prenatal controls, participates in preparation courses for delivery, and has sought information about the gestation process, delivery, puerperium, and caring for the child. Her partner accompanies her to all the activities related to her gestation process. She constantly sees herself as a mother and, together with her partner, has started a special savings fund to have resources that favor purchasing the necessary elements to receive the newborn and cover her needs.

Limit case

Sandy is a 35-year-old woman in her second marriage. Currently, she has two children from her first marriage and lives in a neighborhood where most women are homemakers. Since she got married, she wanted to have a child, but waited one year to do it. Not long ago, she discovered she was pregnant and her happiness could not have been greater. She began her prenatal controls, but could not attend the preparation activities for delivery and motherhood because of a shortage of time. Her husband accompanies her to most of the prenatal controls. Sometimes, she considers she should change some practices as a mother to avoid repeating them with her new child, but thinks it is quite difficult. Although she has some savings with her husband, she always thinks that soon there will be three children to support and that is costly.

Contrary case

Alba is a 21-year-old woman who got pregnant by her boyfriend with whom she has been involved for two years. She is very concerned because in her house they expected her to be married before getting pregnant, besides because her boyfriend has to go off to the army for at least two years; she decided not to tell him or anyone else. This decision keeps her from entering prenatal control; due to her worry, she does not eat because she is not working or studying. After some days, she decided to tell her closest friend and adds that she does not want to be a mother, not under these circumstances and not alone, she feels very insecure and scared, thus, with her friend’s help she decided to give up this new being for adoption.

Empirical references

Table 1 displays different instruments identified that measure in tangential and limited manner some attributes of the preparation for maternity.

Discussion

The aim of this concept analysis was to provide a clear and comprehensive definition of preparation for maternity during gestation. In spite of having identified a varied amount of attributes, all converged in particular manner to understand the complexity and multidimensionality of preparation during the gestation period to becoming a mother. Although the literature review was exhaustive, the production of knowledge is scarce on the preparation for maternity during the gestation period and the studies included in this concept analysis were few and some of them were conducted with a qualitative approach in which the preparation was not consistently developed as category, subcategory, theme, or pattern. Additionally, the quantitative studies did not measure preparation as a concept, but that evaluated was a program configured as preparation to accomplish some outcomes, specially maternal and perinatal. Many of the quantitative studies aimed more exclusively to measuring the preparation for the delivery.

The few revisions included, all thematic, and the book chapters make a brief description of preparation as an additional step for the transition to maternity and involve aspects that go beyond the gestation period, suggesting the preparation as a continuum, but not managing to define what corresponds to the gestation stage. Although the prior statements can be considered limitations in this concept analysis, it is also true that the sources included and reviewed permitted perceiving two big components of this concept. A first component is psychological preparation that seeks to place women in two essential scenarios; the first, within an imaginary scenario of the mothers they can become28 and the second, the retrospective scenario of what their perception was about their mothering role in the upbringing.22 Both situations pose a race toward the equilibrium between that received and what will be provided and offers a unique opportunity to the woman to rethink and reorganize aspects of her past and future life with her and with her close and significant beings.

The second component is the physical preparation that favors in future mothers behavioral changes and habits for their health and that of the child expected (37) through knowledge mediated by the information consulted or received through participation in support groups, group education activities, or attendance to prenatal controls.32 Additionally, through the availability of financial resources that favor the acquisition of care giving elements and the adaptation of spaces9 and the preparation for labor and delivery.22 In other conceptual developments, preparation for maternity has other legal, spiritual, and historical dimensions;9 but is placed within a context reduced to the presence of a relationship between a man and a woman, with a planned pregnancy and extended to the child’s first year of life. This definition generates restrictions upon understanding the concept in practice and in the daily lives of many women who are not in a relationship and who have an unplanned pregnancy. Furthermore, the moments in the transition to maternity, as exposed by Mercer4, differ in the activities that consolidate this role. Hence, managing to separate the constituent elements of the preparation for maternity during gestation from the preparation that may occur in other stages, like postpartum or the child’s first year of life, is fundamental because - currently - programs for the care of women who will be mothers focus mostly on the prenatal period. In consonance, this concept analysis provides a clear conceptual framework that can be transferred to practice by constructing assessment items in the nursing prenatal consultations. It also offers the design of scales for research on the preparation as a multidimensional process or application in maternal nursing practice, as an evaluation element of the current conditions of a woman’s preparation for her transition to maternity.

At the same time, it provides huge intervention possibilities by nurses. Mercer41 had already identified some of these, but this conceptual development favors more detailed comprehension of those essential elements that must be kept in mind to promote, strengthen, and intervene in pregnant women around preparation as a vehicle to achieve optimal results in physical and psychological sufficiency and, thus, confront the care and protection of a new being and their relation with it and the other people who make up their life circle. The evidence incorporated in this concept analysis permits proposing that it is during gestation when the initial and most-transcendental preparations must be carried out and to assume maternity as a new way of life. Mercer4 indicates that preparation during the antenatal period has important repercussions in the lives of the woman and child in subsequent phases of the process of becoming a mother; thus and in sum, it did not manage to contribute theoretically to understanding the preparation within its first stage toward the process of becoming a mother.

In the theory by Mercer,4 preparation appears as a word that accompanies another two: attachment and commitment; it is conceived that the re-conceptualization task will offer elements that would favor understanding these words as concepts, their propositions, and the relations among these and the other concepts of the theory, as proposed by Fawcett.42 The case is that this has not happened to date, nor do the different articles included show a connection of their reflections with the theory proposed by Mercer. Consequently, this concept analysis contributes to clarifying theoretically what is understood as preparation for motherhood during gestation, which matches the first stage proposed by Mercer4 that according to her new theory occurs during this period. This work can be the starting point for research related to the design of instruments, with correlational studies and all those that permit validating, refuting, rethinking, and transforming the propositions proposed herein; especially, studies with qualitative approach where the participants are women during their gestation period, not post-partum women with retrospective interviews.

Finally, some limitations exist in this analysis. First, only the principal researcher reviewed the articles, which is why this situation is probably considered as selection and information bias. Second, exclusion of articles in languages different from English, Spanish, or Portuguese can contribute to selection bias, given because this does not permit understanding a phenomenon of universal nature in its full cultural spectrum. Third, limited clarity in many of the articles on preparation hindered somewhat the abstraction and elaboration of the attributes and the definition of the concept. It may be concluded that nursing professionals dedicated to maternal care meet numerous pregnant women daily and focus their assessment and interventions on the physical changes derived from the physiological process of gestation. The results of this concept analysis will help to broaden the corpus of theoretical and practical knowledge around the preparation for maternity during this gestation period, as well as to provide a path to broaden the care actions within the evaluation and prescription beyond focusing on purely biomedical issues.

According to the findings, as much as the limitations, there are various suggestions for future research, like, for example, identify the behavioral patterns, perceptions, and practices around the meanings of the preparation for maternity during gestation in different contexts and different groups of women. Likewise, quantitative studies need enhancement regarding correlational and causal techniques that permit explaining the preparation as an outcome and its relation to results in the short, mid, and long term. Finally, this work favors the elaboration and validation of instruments that permit measuring this concept that contribute not only to the theory and to the research, but also to the nursing practice.

text in

text in