Introduction

Breast cancer is one of the most frequent and feared diseases among women. It has negative impact given its severity, unpredictable evolution, mutilation and self-image alterations that compromise physical, psychological and social aspects and affect women’s quality of life (QoL). Antineoplastic chemotherapy is one of the most important forms of breast cancer control and represents an advance in its cure.(1) However, despite prolonging life and improving prognosis, chemotherapy is associated with a lower global quality of life (GQoL) score, possibly related to its toxicity and serious side effects.(2) Both the diagnosis and chemotherapy change patients’ routine and QoL. They lead to negative feelings due to the uncertainty of prognosis, possible surgical processes, and coping with the possibility of death.

The search for improved care and QoL of women with breast cancer undergoing chemotherapy is an important aspect to be measured because this assesses the disease dimensions and creates parameters for daily healthcare practices in health services.(3) Thus, by assessing the QoL it is possible to verify the treatment and impact, and plan nursing actions for patients’ adherence and rehabilitation, and better QoL conditions during treatment and survival. Knowing the sociodemographic profile of women with breast cancer is key to provide targeted and comprehensive care according to each moment of the therapeutic treatment. Highlighting possible profile differences according to the care institution may alert the health team to perform actions, guidelines and care adjusted to women’s needs and reality. The physical, emotional, social and cognitive impacts must be constantly evaluated to provide accurate care to women experiencing breast cancer, from diagnosis to the end of life.

Thus, the objective of the present study was to evaluate and compare the general quality of life and sociodemographic and clinical profile of women with breast cancer undergoing chemotherapy treatment at a public and a private institution.

Methods

This is an observational, longitudinal and analytical study. It is part of the thematic project entitled ‘Quality of life of cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy’. The study was conducted between October 2012 and May 2015 in chemotherapy outpatient clinics of a private and a public institution considered reference in the care for this patient profile. Both clinics are located in the city of Curitiba, state of Paraná, southern Brazil. The non-probabilistic sample consisted of all eligible women during the study period. Inclusion criteria were: female gender with proven diagnosis of breast cancer, aged over 18 years, no previous chemotherapy treatment for cancer and indication for initiation of chemotherapy. Women on palliative therapy and had lost follow-up were excluded. A total of 131 women were selected, of which 16 were ineligible because they had not been approached before chemotherapy.

In the first stage of the study, 115 women participated in the study, of which 48 were from the private institution and 67 from the public institution. In the second stage, which occurred between 40 and 50 days after the first administration of chemotherapy (period of adverse effects occurrence),(4) a woman was discontinued in the public institution. In the third stage, 85 to 95 days after the first, (period of control of adverse events),(4) five women were discontinued in the public institution. In the private institution there was no discontinuity in any of the stages. Discontinuations occurred because of chemotherapy toxicity or loss of follow-up between the second and third stages. A total of 791 questionnaires were collected in the three stages of the study.

Three questionnaires were used for data collection. Questionnaire 1 had sociodemographic and clinical data, and was applied only in the first stage. Questionnaire 2 was the Quality of Life Questionnaire-C30 (QLQ-C30), developed by the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC), version 3.0, and was used to assess the QoL of cancer patients. Questionnaire 3 was the Quality of Life Questionnaire - Breast Cancer Module (QLQ-BR23), and applied in the three stages. It is directed to the basic disease with issues related to breast cancer, version 1.0. The QLQ-C30 and QLQ-BR23 questionnaires used were the translated and validated versions for Brazil.(5)

The analysis of sociodemographic and clinical data was by absolute and relative frequency. Data from the QLQ-C30 and QLQ-BR23 questionnaires had a 0-100 score according to the Scoring Manual of European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer.(6) For QoL-related scores such as emotional functioning, the closer to 100 represents greater functionality and corresponds to a better QoL. For the comparison of data between institutions, was applied the non-parametric Mann Whitney test, and for the comparison of stages, was applied the Friedman non-parametric test complemented by the Least Significant Difference Test (LSD), considering p≤0.05 as significant. All ethical precepts were respected in the study, and both questionnaires were authorized upon registration of the project with the EORTC. It was approved by the Ethics and Research Committee under protocol number 5301 for the private institution, and number 518.067 for the public institution.

Results

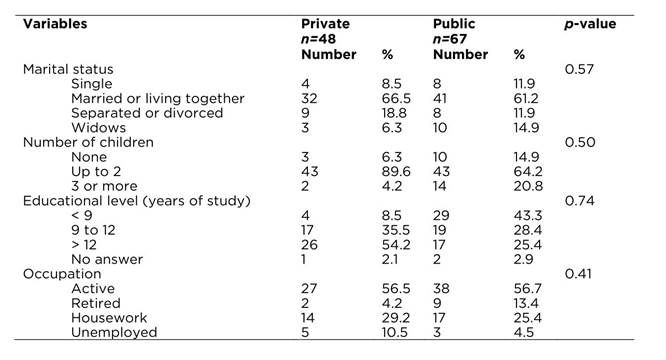

In the present study, participants’ mean age in the private institution was 46 years (min = 24, max = 69), and in the public it was 51.3 years (min = 30, max = 77), which was a significant difference (p=0.02). Table 1 shows sociodemographic data of the 115 participants. Regarding women’s educational level, in the private institution 54% (n = 26) had complete higher education, whereas in the public institution 43.3% (n = 29) had less than nine years of study, which includes incomplete or complete primary education. The family income in minimum wages was another highlight; in the private institution, the average income was 12 salaries (US$ 3,069.76), while in the public institution the average was 2.8 salaries (US$ 716.27).

Table 1 Sociodemographic characteristics of women with breast cancer undergoing chemotherapy according to type of institution. Curitiba, PR, Brazil, 2015

In relation to clinical data (Table 2), in the private institution 68.5% (n = 33) reported having no comorbidity. In the public institution, hypertension stood out in 35.8% of women, and 49.3% reported not having any secondary diseases. Clinical stage III was frequent in 82% and 39.5% of women in public and private institutions, respectively, and AC-T (Adriamycin® and Cyclophosphamide® followed by Taxol®) was the most used protocol.

Table 2 Clinical characteristics of women with breast cancer undergoing chemotherapy according to type of institution. Curitiba, PR, Brazil, 2015

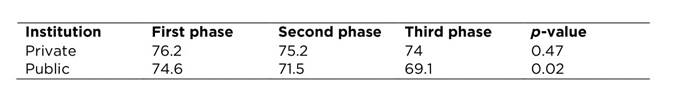

The QoL results were evaluated with the QLQ-C30 questionnaire, the Global health status in the private institution was considered satisfactory with a value of 76.2%, but it declined in the second and third phases. In the public institution, there was also a decrease between the first and third phases, but in this institution the change was greater. As for significant differences between phases, the p-value of the Global health status in the private institution was 0.47, and in the public institution was 0.02 (Table 3).

Table 3 Global health status scores of women with breast cancer undergoing chemotherapy according to stage of treatment and type of institution. Curitiba, PR, Brazil, 2012-2015

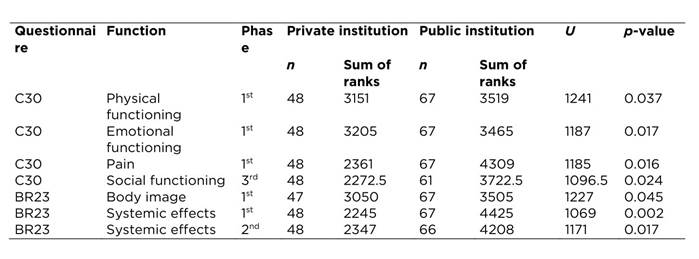

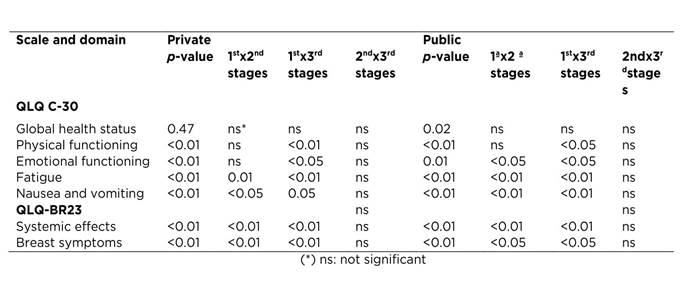

Still in the comparison between treatment phases with the QLQ C-30 questionnaire, in the public institution were observed significant changes in values of physical and emotional functioning, fatigue, nausea and vomiting, and in the private institution, in physical and social functioning, fatigue, nausea and vomiting. When using the QLQ BR23 questionnaire, in the private institution, the systemic effects and body image stood out, and in the public institution, systemic effects and breast symptoms had significance (Table 4).

Table 4 Significant domains between chemotherapy treatment phases in women with breast cancer by type of institution. Curitiba, PR, Brazil, 2012-2015

When comparing institutions (Table 5) using the QLQ-C30 questionnaire, the significant domains in the private were emotional functioning (first phase) and social functioning (third phase). In the public institution, physical functioning and pain (both in the first phase) were significant.

Discussion

QoL studies in women with breast cancer aim to identify the impact of diagnosis, treatment, adverse effects and biopsychosocial needs throughout the course, allowing that nurses plan actions to improve these women’s living conditions. In this study, the public institution reveals a more heterogeneous population in relation to age, educational level and professional occupation. Socioeconomic conditions are less favorable with less access to health services for periodic follow-up, and when it is done, greater time is required for diagnosis given the available resources in gratuitous care.

The private institution characteristic is also a component to be considered as it can show specific results for this scenario because of the population’s social characteristics. In private institutions, women often have more favorable socioeconomic conditions and access to health services because of the possibility of payment, and this aspect facilitates routine examinations and frequent consultations hence allowing an early diagnosis.

In the private institution, the mean age was lower than the national. This is an uncommon fact in the literature that constitutes 5 to 7% of breast cancer cases. In contrast, in the public institution, women had an average age similar to the national of around 50 years.(7,8) The explanation for this condition can be that younger women at reproductive ages are more likely to seek medical service, therefore are more examined, which can provide an early diagnosis of the disease.(9) However, statistics predicting breast cancer in relation to age are changing, and the results of the research in the private institution corroborate with this information. These studies(10,11) show the predominance of age groups below the national average, with increased number of cases as women’s age increased. International studies are in contrast to the findings of the present study, and indicate the occurrence in the age group over 50 years, women’s mean age of 61.8 years in Sweden(12) and 58 years in the United States.(13)

In addition to the age group, other factors deserve health professionals’ attention, such as educational level and socioeconomic status. In the private institution, several women have studied more than 12 years, but in the public institution, many women studied less than nine years, which demonstrates the educational level difference between women with breast cancer in chemotherapy treatment at the two institutions. This corroborates the fact that the higher the educational level the greater the insertion of these women in the labor market, and consequently, the greater knowledge about prevention methods.(14)

According to Rosa and Radünz,(15) low educational level may be tied to low socioeconomic status. That was also a finding in the present study, in which around 56% of women in the private and public sectors were economically active. However, the average family wage in the private institution was high. In the public institution, in turn, it was characterized as low socioeconomic status. Simeão et al.(16) emphasize that similar socioeconomic and cultural level characteristics allow a better understanding and planning of the needs for the physical and psychological benefit of affected women. In contrast, economically active and productive women suffer a greater impact on QoL after diagnosis and treatment, triggered by the feeling of impotence in the face of illness, of their social and family life, and fearing the future for the uncertainty of the present, because they conciliate job activities with the treatment.(17) In counterpoint, authors(2) of a Chinese study highlight the association of a high family income with better QoL of patients with breast cancer in each measured domain. Guidelines and approaches to this group need to be conducive of effective communication throughout treatment by alleviating stressful effects resulting from changes in their emotional, social and family life.

The comparison of clinical staging between institutions showed the public institution had 42.5% more women with stage III than the private institution. This demonstrates women start treatment in more aggressive stages of breast cancer in public institutions, and the access of women from a private institution is more precocious. These data corroborate with the study in Africa. The objective was to understand the late diagnosis and impact of the stage of breast cancer among Libyan women. Stage III was the most expressive, with a diagnosis time of more than six months, which potentially results in high mortality rates.(18) The late diagnosis is focused on several factors related to the population’s characteristics, low educational and socioeconomic level, and tracking policies, which make the access to early diagnosis difficult, worsens the prognosis, and leads to more aggressive treatments with impact on women’s survival and QoL. Health professionals’ interventions should be performed at all levels of care to provide agile assistance and according to their reality. QoL is a multidimensional construct that allows identifying the psychosocial aspects altered by cancer and its treatments. It is a support tool for nurses and other professionals in the management of alterations in women with breast cancer.

Data from QLQ-C30 questionnaires at the private institution show a higher QoL score compared to the public institution. However, the same domains are scored in both institutions: physical functioning, emotional functioning, fatigue, nausea and vomiting. These are common effects in patients receiving chemotherapy for breast cancer. In both institutions, most women with breast cancer arrived for treatment already in stage III, leading to the choice for the most aggressive therapy that causes greater decline in physical functioning. A Brazilian study with the same population profile is in agreement with these data.(1) It shows physical functioning with lower means, 60.5% and 64.43% respectively, which characterizes impairment in this domain with a decrease in QoL.

Accordingly, a study in Turkey that evaluated QOL and nursing care satisfaction during chemotherapy using the FACT-G questionnaire demonstrated the domain of physical well-being was compromised, with the score of 14.85%, which evidenced that more advanced stages experience more physical symptoms than initial stages.(19) In contrast, Hoyer et al.( 12) observed scores greater than 80% in physical functioning among Swedish women on chemotherapy, and mean values above 75% also for social functioning, indicating no impairment of QoL in relation to these functions. Analogous results were found in a similar study conducted in Malaysia, with mean values above 75% for physical and social functioning, which positively characterizes the maintenance of living conditions, and social and leisure activities among affected women.(20) The impairment of physical and social functioning reflects a reduction in the socio-occupational participation of these women regarding their involvement in daily situations often impaired by decreased mobility in the homolateral arm of breast cancer(1) that results in worsening QoL concerning these domains.

Emotional functioning was compromised in the three phases in both institutions, showing that patients were worried, fearful and emotionally fragile throughout treatment, compromising QoL in this domain. In their studies, authors(1) emphasized marked changes in emotional functioning, with mean values of 48.4%, which indicate the QoL impairment of patients undergoing chemotherapy. Women with breast cancer live with emotional disorders daily, such as feelings of imminent death and fear, and behaviors caused by the threat of cancer given the actual or idealized proximity of incapacity or risk of life that lead to fear, anguish, shame, and feelings of discrimination that are difficult situations to be embraced emotionally by patients.(1,3)

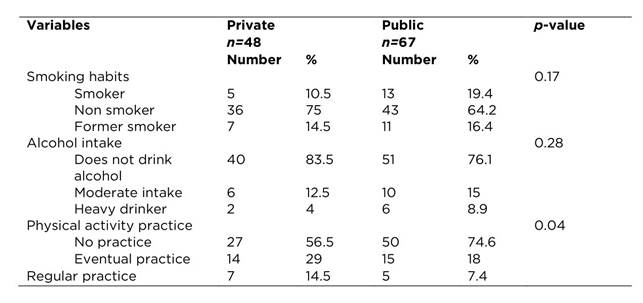

A study conducted in China,(21) assessed the relationship between depression, anxiety and QoL of 269 women during treatment, and 148 women who had completed treatment one year before by using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Cantonese/Chinese version and FACT-G questionnaires. It showed an association between high levels of anxiety with worse physical and functional functioning, and impairment in emotional functioning during and after therapy. This indicates an impairment of QoL regardless of social status, staging and modality of treatment. The QLQ-BR23 questionnaire scores show there is a singularity in relation to systemic effects, but with significance for the public institution. Patients of the public institution had significant scores when evaluated in relation to systemic effects of chemotherapy. This may occur because of the treatment aggressiveness at more advanced stages of the disease. Another aspect to be considered is that women attended at private institutions often have access and better conditions to obtain medications that minimize side effects.(14)

Other results presented with the QLQ-BR23 questionnaire showed a significantly higher score for the private institution related to body image, and in the public institution for breast symptoms. It is noteworthy that breast cancer therapy can affect several dimensions of women’s lives. It is directly related to the symptomatology and women’s perception of their body image, besides compromising the QoL.(14) The altered body image is an uninterrupted sign of the presence of cancer that maintains and aggravates feelings of anxiety, fear, revolt, and psychologically affects women’s interpersonal relationships. Therefore, cancer nurses must develop actions to favor and stimulate social, family, affective, and sexual life, and the QoL in relation to self-image.

The emotional and social reactions caused by breast cancer diagnosis in the life of a woman are singular. She receives the news of cancer as something unexpected, threatening, capable to reach the integrity and proof of female existence, since breasts are the symbolism and concept that women make of themselves. Feelings of death, stigma of mutilation and feelings that may alter self-esteem can cause change and devaluation of these patients’ social aspect.(22) In a comparison between institutions regarding altered domains in quality of life, there was a higher score for social functioning in women under care in the private institution. It is noteworthy that these women have higher educational level, high family income, and are inserted in the labor market. As treatment is long and mutilating, it takes them away from their routine, which possibly led to the direct alteration in this domain.

In the public institution, pain was a significant factor in the change in QoL. This fact can be justified by the high number of late diagnoses that result in more discomfort to women, and more aggressive treatments. Like fatigue, it is a frequent, persistent symptom that causes physical and emotional exhaustion to patients and their families because of difficulties in daily activities and self-care, changes in mood and concentration.(23) In the study by Guimarães and Anjos,(24) pain was identified before chemotherapy in 20% of the women, with increased mean values, intensification of the symptom during therapy, and losses in the QoL. It reverberates in daily life with emotional, social and functional impairment, and prevents women from performing their routine activities. Measuring pain is one of nurses’ actions and it requires knowledge of evaluation methods and factors that trigger and overcome this symptom by considering its subjectivity.

In nursing care for women with breast cancer, the prediction of coping strategies that preserve self-esteem, social and emotional functioning, and physical effects of cancer and chemotherapy treatment should be part of the daily life of these professionals. The bonding between women and nurses during this period may help women to better understand their body changes, making the process of coping with the disease less stressful and exhausting(25) and consequently, resulting in a better QoL. A limiting factor in this study was the size and lack of randomness of the sample. The reduced number allows to consider the findings only for the population in question. It was also difficult to find studies comprising results in mixed institutions for comparison with our data.

Conclusion

In this study, were investigated the possible impacts of breast cancer and chemotherapy treatment on women’s QoL in public and private institutions. Chemotherapy deteriorated women’s QoL in both institutions, and it was lower in patients at the public institution. Differences between public and private institutions may impact the QoL differently. In the study, the only difference found in women’s characteristics was their age at the time of diagnosis, which was lower in the private institution. Nursing should have a better understanding about the type of institution responsible for women’s care in order to identify the domains and affected symptoms, which will allow the provision of comprehensive care to these women at each phase of treatment hence improving their QoL.

text in

text in