Introduction

Rapid response teams (RRTs) first appeared in Australia in the early 1990s. They aim to bring knowledge and skills for the critical care of patients with signs of physiological deterioration, at sites outside the intensive care unit (ICU), in a timely manner to avoid adverse events.1 The RRTs are systems composed primarily of two components. The first is called afferent team, which is next to the patient providing the normal care and with the appearance of signs of deterioration is to trigger a call to the efferent team, respecting assessment criteria. The efferent team responds to the call and conducts rapid and necessary measures to avoid worsening and death.2 With the creation of the teams, several studies were carried out that evaluated their efficiency in hospitals. A significant reduction was observed as to the number of cardiorespiratory arrests (CRAs) and mortality of patients who showed signs of clinical deterioration.3 However, other studies have not shown effectiveness of RRTs concerning the same parameters.4 In order to clarify these differences, a recent meta-analysis5 was conducted that evaluated 29 studies and concluded that the presence of RRTs reduces rates for hospital mortality and CRAs. However, it was suggested that there are factors that can interfere with the quality of the outcomes and that should be better elucidated. Therefore, this study aims to review the literature to determine the main factors that can interfere with the performance of RRTs.

Methods

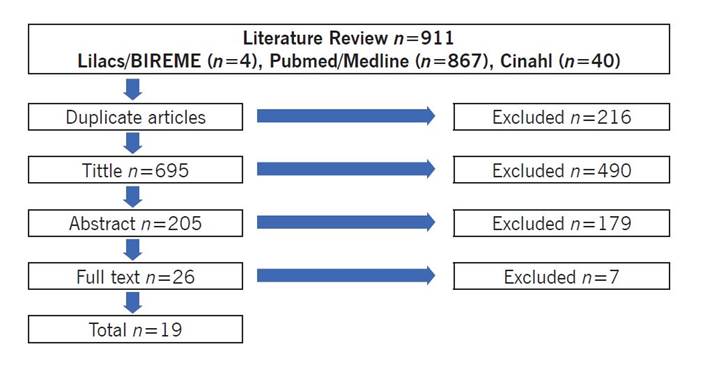

This is a literature review of scientific articles (clinical trials, observational studies, and qualitative studies) published from January 1, 2006 to July 25, 2016, in Portuguese, English, and Spanish. The databases researched were PubMed/Medline, Lilacs - Bireme e CINAHL. The keywords used in the search were "hospital rapid response team," "cardiac arrest," and "hospital mortality" and their respective terms in Portuguese and Spanish. The search strategies used were the following associations of keywords: "hospital rapid response team" AND "cardiac arrest"; "hospital rapid response team" AND "hospital mortality"; and "hospital rapid response team" AND "cardiac arrest" AND "hospital mortality." We included studies that described or evaluated one or more factors that could interfere with the performance of RRTS, both those with quantitative and qualitative characteristics. There was no restriction as to the studies’ countries of origin; however, we included only the complete articles published in Spanish, English, or Portuguese. We excluded the literature reviews and editorials because it did not present intervention methods.

Four phases for the selection of studies were previously defined. The first phase was the exclusion on articles that were repeated in the databases; in the second phase we excluded studies that did not address the proposed topic in their titles; in the third stage we excluded studies that - after reading of the abstracts - were found to not address the research topic; and, finally, in the fourth stage - after complete reading of the articles - we excluded those that did not address the research question. In the first and second stages the exclusion of the studies was done by a principal evaluator; in the other stages, two reviewers carried out the reading and agreed to include only articles that answered the research question. At the end of the steps the selected studies were analyzed and classified according to the study objective and interference factor tested using the comparison method. From the classification it was possible to categorize the studies that tested the same interference factor.

Results

We selected 19 studies to compose the integrative review, as described in Figure 1. After analysis and classification, the studies were organized into categories according to the assessed interference factor. As follows: sociocultural barriers and institutional policies, delayed RRT activations, composition and/or capacity building of teams, use of enabling tools for RRTs.

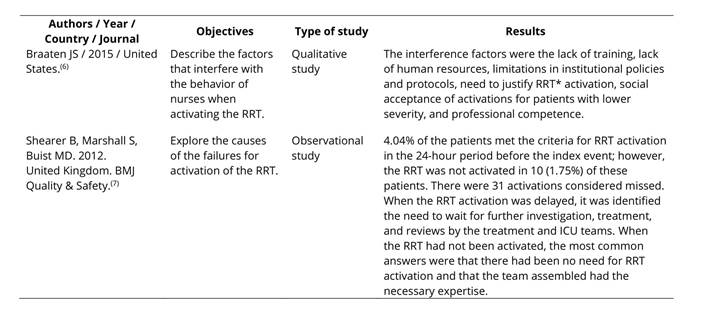

Sociocultural barriers and institutional policies

Two qualitative studies investigated what factors influenced the performance of RRTs. The results of these studies, as described in Table 1, pointed as limiting aspects: the sociocultural barriers such as interprofessional hierarchy and beliefs. Firstly, due to believing that the afferent team needs to provide justifications when activating the efferent team. Secondly, due to believing that the specialized afferent team should be sufficient to resolve adverse events. Other factors were the lack of training of professionals and lack of human resources to meet the demands of patients, as well as limitations in protocols and institutional policies.6,7

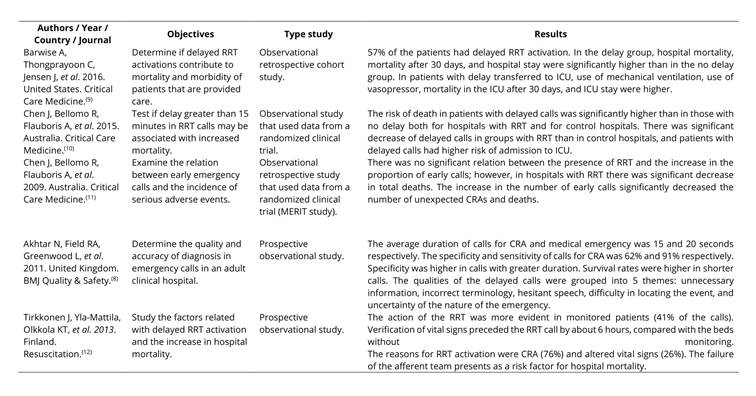

Delayed RRT activation

In Table 2, the articles showed that delayed RRT activations are associated with increased hospital mortality rates, length of hospital stay, number of CRAs, and higher risk of admission to ICU.8-11 For patients admitted to ICU there is also increased mechanical ventilation time, length of hospital stay, and death.9 There was no reduction of delayed activation even with monitoring of patients.12 The causes for delayed activation were described as the presence of unnecessary information reported during the activation, hesitant speeches, and difficulty in locating the emergency event.8

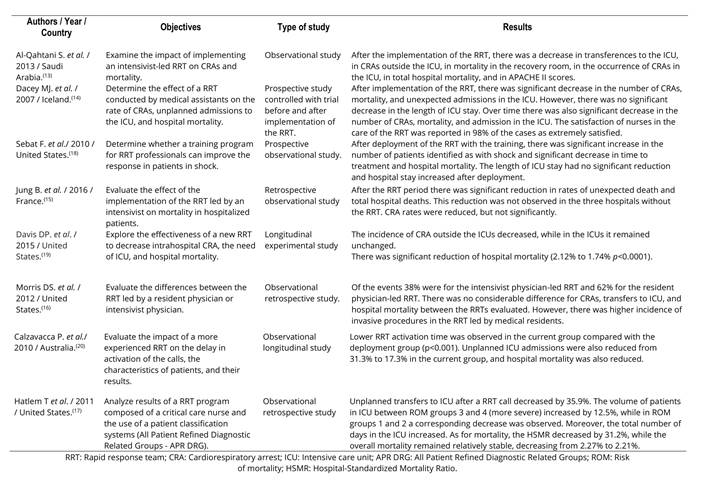

Composition and/or capacity building of teams

We selected 8 studies (Table 3) that showed that RRTs led by intensivist professionals or professionals with experience in critical care can reduce hospital mortality and the number of CRAs, unplanned ICU admissions, and decrease disease severity scores.13-17 The teams were mostly composed of doctors, nurses, and physical therapists with experience and/or specialization in critical care.13-20 Some studies included a pharmacist, laboratory technicians, radiology technicians, and administrators and clinical secretaries.13,16-18,20 It was shown that the presence of a resident doctor in the team represented no difference when compared with the responsible intensivist.16 Capacity building and maturation of the teams can improve the outcomes, reducing mortality and unplanned ICU admissions as well as enabling shorter activation time for efferent teams.18-21

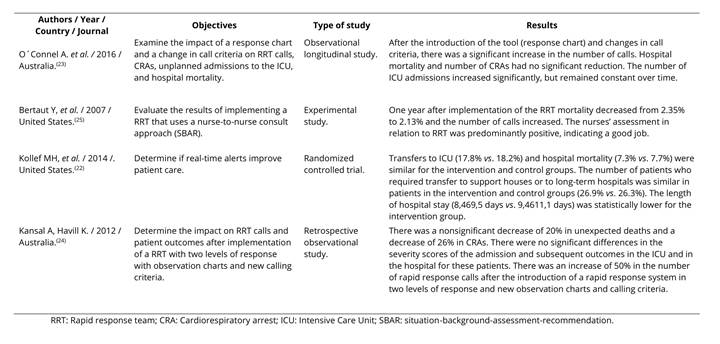

Use of enabling tools for RRT

Four studies evaluated some enabling tools for the success of RRTs, as shown in Table 4. These tools were described as early warning systems, new activation criteria, two-level response systems (early and late), and case handoff tools. Early warning systems functioned as a digital program that through electronic medical records could detect changes in the patient's vital signs in real-time and thus promote earlier detection.22 New activation criteria corresponded to instruments to observe the patients’ vital signs with definition of new criteria for activation of the RRT and that were completed by the afferent team.23 The two-level response system consisted in coordinating the response, in the first instance the patient was provided care when there were minor changes in vital signs by the afferent team (early) and if the patient remained with worsening of clinical condition there was activation of the second level of response executed by the efferent team (late).23,24 The case handoff tool evaluated was the SBAR (situation-background-assessment-recommendation), which aims to enhance communication among nurses and optimize response time for critical patients.25 The use of all tools did not show a significant reduction in patient mortality.22-25 However, there was an increase in the number of team activations when using new activation criteria, two-level response system, and case handoff tool23-25 and a decrease in length of hospital stay when using an early warning system.22

Discussion

This study through a broad literature review provided the determination of four main factors that interfere with the performance of RRTs. Categorization of these factors can enable access by professionals to this information and improve their understanding of it, consequently, contributing to institutional planning in health. With the growing demand for quality care in critical patients2 it is necessary to understand the causes of failures in the provision of care of these RRTs, enable better planning of actions to correct and remodel systems and thus provide better safety to the patient. Health safety policies require scientific foundations that ensure health care with minimal adverse events as possible, which makes it essential to know elements that lead to inefficiency of these assistance systems.

Sociocultural barriers were underlined as elements that interfere with the quality of the care provided by RRTs and derive from the creation of a nightmarish institutional culture among the professionals, particularly concerning the activation for efferent teams of the RRT. The need to justify the activation, as observed in this study, come from the establishment of a criticism culture in which early activations are deemed "unnecessary".26 In this context, the professionals’ lack of training can generate fear in activations, as they feel embarrassed to show little knowledge of the critical situation and consider themselves unable to handoff the case of the patient to efferent teams.27 Institutional culture, therefore, can adversely influence professionals towards not executing activations in the correct time and consequently causing delays and worse outcomes.27 This finding was also observed in the study of Tirkkonen et al. 2013, in which even with the identification of signs of clinical deterioration in the patient by monitoring, RRT activations remained late.

Institutional policies intended for professional valorization and training can reduce these barriers as they build a new culture, in which professionals can activate calls without being criticized and focus only on patient safety.26 The presence of interprofessional hierarchy can also interfere negatively. Other studies that have also observed delays in the activation of RRTs identified as one of the causes the hierarchical model in which the nurse of the sector where the patient is must first contact the local doctor before activating the RRT. Training the members of the multidisciplinary team in order to develop their professional autonomy in the workplace can assist in interprofessional relationship and avoid these limitations and impositions from a profession on the other.28

Delays, on the other hand, can be caused by the afferent teams’ failure to recognize the signs of early clinical deterioration in patients. These attitudes occur both due to the professionals’ lack of adherence to the protocols and criteria for activation of calls and to the lack of human resources to meet the patients’ demand.26 The proportion of human resources in relation to the number of patients is a factor that is still questioned, and there are studies that relate the increase in the proportion of nurses with the reduction in mortality of patients; however, there are still limitations to demonstrate that the increase in the number of nurses can become a patient safety strategy.29 Regarding the professionals’ lack of adherence to protocols, it was observed that better knowledge and familiarity with the instruments of criteria to evaluate the signs can increase adherence to activation of the teams, avoiding delays.30

The team’s composition may vary for each hospital, and most have a doctor leading the team. The need for the doctor in the RRT as a factor that can interfere with its efficiency is still controversial. Although most hospitals use the doctor as head of their teams, a meta-analysis did not show that the presence of the doctor is associated with better outcomes.5 What has been observed is that when the professionals have experience and/or specialization in intensive care, the teams can achieve better outcomes.31 In order to improve the RRT responses, tools and instruments have been devised that help professionals in the detection of signs of clinical deterioration, as well as in the team activation process and patient case handoffs. Contrarily to what was found in this review, in some institutions the use of evaluation instruments led to lower rates of mortality and CRA events.32 It is probably explained by the presence of programs of continuing education and training to employ the tools appropriately, which shows that, as much as the tools are useful to improve response, without the proper training for their use they may not bring clear benefits.32

This review presents limitations: firstly, due to the fact that instruments have not been used to assess the methodological quality of the studies identified; secondly, due to the existence of few controlled and randomized clinical trials that addressed the research question. However, this study was conducted based on a wide search in the literature in the world’s main databases and managed to summarize the main aspects that can influence the performance of RRTs. Thus, it can guide health professionals and health managers to identify the flaws in their institutions in order to promote corrections and better results. Individuals who need critical care will be safer and with better chances of survival.