Introduction

Nursing care is the way of helping people during an interaction process,1 or what is denominated, a phenomenon of human transaction in which nurses assume their potentialities and weaknesses to help others in an honest and selfless manner. This reciprocal interaction is the best valued by patients because it provides care aimed at wellbeing, communication, intimacy, trust, and security, which generate better results and higher satisfaction in patients and families.2) And, although nurses during their hospital practice reflect upon the actions and interactions they have with patients,3 several factors impact upon the way of interacting with them in the hospitalization services and which distance them from the care actions defined as essential pillars of the work of this profession. Hence, invisible care for nurses is defined by Huércanos4 “as the intentional care actions that are not registered, whether because of inadequate registry systems, or due to the scarce value they assign to those actions”. It seems, then, that this type of care becomes invisible because these actions that seek to safeguard the patient’s intimacy and dignity, preserving the privacy of their own body, are delegated or are simply not registered, which generates the loss of its importance against others that for the institutions are more valuable. Added to the aforementioned, diverse changes in the economic, political, and social dynamics have derived in the way the caring practices acquire a form of invisibility or intangibility.5

Thus, the emphasis in the biologist model that assigns greater validity to the medical exercise; additionally, the organizational structures require of nurses greater dedication principally to administrative functions delegated in the hospitalization services.6 This is how interaction and wellbeing actions to benefit patients are not valued or registered, which results in the loss of importance of their execution and, hence, generates the invisibility of the care to patients and to the very nurses. The review of the literature available found no published studies related with this problem within the Colombian and Latin American context on how nurses view the care they provide and how visible it is, besides the recognition of their work and, consequently, from the results be able to reflect on strategies that contribute to the construction of the meaning of care and, thus, add to the development of new theories. The aim of this study was to understand the meaning of invisible care by nurses during their practice in hospitalization services.

Methods

This was a research with qualitative approach and tools from the ethnographic method. From this perspective, the study phenomenon was based on a naturalist paradigm because it focused its attention on the relations created among people who share the same context. Seven nurses participated selected through intentional sampling. The first two participants were received through social contacts of the researcher who is a professional nurse with friends working in hospitalization services; the other five participants were referenced by the first two. None rejected participation or quit during the process. To gather information, the researcher made the presentation and explained the objectives of the investigation. The inclusion criteria of the participants sought to explore the variability of the phenomenon, seeking for the individuals to have different years of experience and ages, as well as to work in different hospitalization services without regard for the specialty.

Additionally, a non-structured participant observation was conducted in an institution different from the one the participants interviewed belonged. It centered on aspects of care during different moments of the day and work shifts, (morning, afternoon, and night), which permitted saturation of the categories emerging from the interviews and focused on aspects of invisible care that have been defined in literature, in the interaction nurses have with patients, the care they provide, and the records they keep of these.

The interviews took place between January and August 2017 in Medellín (Colombia). The principal researcher, who is a nurse specialized in Biomedical Basic Sciences, began gathering information with a guiding question in relation with “speaking of experiences lived during the act of caring in a hospitalization service”. This activity, on average, lasted one hour and took place outside the participants’ work, which offered an appropriate environment for dialogue and without the presence of other people. The principal researcher recorded and transcribed all the interviews within the following 24 h; thereafter, these were stored in a text file. It was not necessary to hold more than one interview per participant.

After transcribing the interviews, it was read in detail, line by line, looking for units of significance; thereafter, manual cards were made with analytic notes that served as guide for the categorization. Finally, with each of the cards a careful reading was made in search of new codes that could emerge in the reports of the participants or in those codes in which emphasis had to be made in the following interviews or observations. The categories were named with live codes. The analysis ended after verifying the data collected and theoretical saturation was reached. During the final analysis process, a conceptual map was created that permitted relating the categories obtained and the different subcategories around the meaning that emerged. For this final process, informatics tools were used favoring the organization of the information, such as Excel® and Cmap-Tool®.

Another data collection technique was observation of the participant during 30 h between April and August 2017, at a tier-III level of care institution, in various hospitalization services (pediatrics, internal medicine, neurology, orthopedics, and surgery) and which had the presence of nurses 24 hours per day and which focused on aspects, like the nurse’s interaction with the patient, the care provided, functions performed and records of activities; the aforementioned, during different times of the day (morning, afternoon, and night). The methodological and analysis data product of the interviews and the observation were recorded in a field diary. The nursing coordinator from the hospitalization area made the researcher be the gatekeeper for the nurses from the hospitalization services to conduct the interview without setbacks.

To guarantee criteria of research rigor, like credibility, auditability, and transferability, the results were socialized with the participants, the institution, and the academic community. The ethical aspects considered in this study included the approval by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Nursing at Universidad de Antioquia, the informed consent signed by the participants and endorsement from the Research Committee from the institution in which the study was carried out.

Results

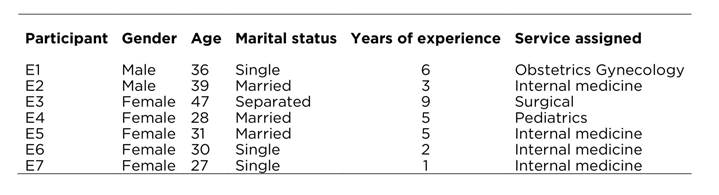

Seven interviews were conducted to an equal number of nurses. Table 1 shows that the participants were predominantly women, with mean age of 34 years; four were single and the other three were married, with hospital care work experience of 1 to 9 years in public or private institutions, with private institutions being the most common and the most-frequent service being internal medicine where four of the seven participants worked.

The findings, herein, accounted for two principal categories: What nurses do and The transformation of the role.

What nurses do

According to the participants, the condition of invisibility of care depends on diverse actions that do not generate economic profit to the institutions; in fact, care actions will be more or less visible according to their impact on fulfilling the institution’s indicators and objectives, as stated by a participant: If you start having problems in the delay of the patient being discharged, if they complain of why they did not get their medications or some other reason, all that affects the hospital’s indicators negatively and shows the lack of a professional there integrating all those things (E4). Thus, invisible care is present in everything nurses do to benefit patients, although it does not always involve their physical presence in their room. This is how for the participants, nurses are in a labor dilemma in which their actions are aimed at providing the best care, without physically moving away from the patient. This way, nurses keep in mind the needs of patients and their families and end up being mediators to solve said needs with the other members of the health staff (physicians, nursing aides, nutritionists, psychologists, administrators and nursing coordinators, and other nurses). The difficulty nurses find in this mediation is invisible for everyone else. Thereby, according to the participants, nurses perform actions that seek the wellbeing of patients and their families, less complications in health, rapid return to their homes and for their relatives to be trained and able to offer effective companionship. Nevertheless, these actions are carried out without patients realizing it, as shown by the testimony: (…) I can waste many hours of my time seated by the phone managing things for the patient to be discharged well and nobody realizes this because that is not recorded anywhere (E6).

Transformation the of role

Consequently, nurses cannot provide all the direct contact they wish with patients and families; they feel that all those functions as mediators distance them from their patients, and gives way to the transformation of the nurse’s caregiver role in hospitalization services with three subcategories described ahead:

Priorities of the nurses: “What they should do”

According to the participants, the work performed by nurses in the hospitalization services depends essentially on what their priorities are: what they should do as nurses, the actions to carry out to defend their professional position and the evaluation of the art of nursing care - understood by them as all the skills to be able to care: (…) care refers to the bond I have with my patient and it is a personal link, face to face, where I manage to empathize with my patients and understand their needs. Patients need care, they need you to be there, to keep them company, to ask if they are hungry, help them eat, things like that (E4). This narration shows that the participant prioritizes activities framed within the direct care of people and the satisfaction of their basic needs, and no other functions.

Priorities of the institutions: “That which has to be done”

Additionally, nurses also perform actions that distance them from their patients and which depend specially on the administrative functions assigned by the institutions and that are aimed at maintaining management indicators, management of human resources, or others that are delegated (request for diets and supplies, for example) that limit direct contact with patients and their families: It is very difficult (to comply with functions) because many times the institution demands activities that are not a priority for us (…), like, for example, filling out forms because these are record keeping actions that can wait (E2). In this sense, this narration accounts for how nurses emphasize on the institution’s priorities, which go against their own as professionals. Hence, with the transformation of the role, nurses have had to alter their care object, and without wishing it, have gone onto [caring] for supplies and devices, in other words to watch over, an assignment made by the institution. Thus, for example, is this report of an observation: In a hospitalization service classified as complex, the nurses’ post-reanimation activities center on quickly asking the doctor for the orders to replace with supplies and elements from the cardiac arrest cart that have been used, being on the phone, and writing on the computer. At the end of the hall, a group of five people, who seem to be related to the patient who suffered the cardiac arrest, weep while a nursing aide approaches one of the women, places a hand on her back and speaks with her (OBS2/HOSP). For the participants, the work of nurses in the institutions is framed principally on reaching the indicators that permit evaluating the quality of the service and the institution’s sustainability: With merely one adverse event occurring that affects the statistics and the indicators, they see that more (the negative) than what I am doing well with the patient (E3).

Result of the change: “The unknown nurse”

The participants expressed that many consequences are brought on by the transformation of the nurse’s role in their daily work in hospitalization services. One of these is having to distance themselves from the patients, delegating direct care actions due to having to comply with all the functions the institution imposes on them with the result of invisibility reported previously: The nurse’s activity has been delegated to the nursing aide because in most hospitals the nurse gets a workload or a time different from other types of activities: elaboration of the Kardex, administrative matters and what they (administrators and coordinators) badly call service management, which is where we have ended up (E1). Likewise, the participants stated that nurses feel dissatisfied with their work, feeling that their work is not valued although the institution obligates them to perform tasks that do not generate recognition or are invisibles for the rest: Nurses get tired of the work due to lack of motivation. You have a bunch of responsibilities and things to do that people don’t appreciate and which finally has no valuable essence for the patient’s care… for example: I can have multiple functions in a committee, draw up a record, look for this paper and nobody recognizes that (E6). The participants state that another result of the change is that of having to do numerous activities for which they were not trained in the university or for which they received no preparation or training in the institution. In this sense, beyond requesting preparation to perform these actions, they consider that other staff should perform them and, thus, they could dedicate their time to caring, which is their priority and objective: You are trained in a very beautiful thing and think you will be the super nurse and will do everything for your patients, but when you get here (institution), you find out that it is not only the patient, but also other things that are delegated from the administrative area and I believe those activities could be done by other people (E3).

The participants indicate that in the hospitalization service there is a monotonous routine of work and activities. Independent of the model the institution uses to distribute the staff and their functions, in hospitalization services, during the day and night, nothing that is not contemplated is admitted, like approaching the patient, which can become a complication of the shift because nurses must comply with the institution’s priorities above their own priorities centered on care: Hospitalization services have established routines because you generally have a rather large load of patients, then you have to stick to an established work plan, given that if you get out of that, whether because you wish to go further with a patient or because the work requires it, it all gets complicated (E4).

In addition, the participants highlight, during the daily work of the hospitalization services, that it seems that communication was breached or became ineffective due to the work dynamics. They claim that perhaps in the organization communication was substituted among the professionals and nursing care was rendered invisible by the individualist work of each of the members of the health staff, which complicates interaction visibility processes of the work teams with themselves and with patients. To them, communication is limited to each of the members of the health staff elaborating their care plan, and for the nurse being in charge of unifying them all and in many occasions without their own being considered: who looks at the nursing care plan? Nobody! You look at it and perform its activities among your coworkers and with the personnel under your supervision, but for many other disciplines that is not important (E2).

Lastly, for the participants during the nurse’s daily work, the change of role has given way to the visibility of those members of the health staff who are in direct contact with patients and families, rendering invisible actions nurses carry out without providing direct care: In the care part, the auxiliary staff is more visible; nurses become visible when there are problems in daily affairs because when the patient complains or makes a request, that is when nurses come in and have to talk with the patient or with the relative and see what was the problem (E4).

Discussion

The polysemy of the concept of care is given by the different perspectives from which it is addressed, but the interaction is an almost general trait in the infinity of theoretical definitions. Thereby, for Watson,7 nurses in the act of caring become a therapeutic instrument, given that it merits the exercise of interpersonal relationships to achieve their objective of caring. The findings of the investigation account for the importance nursing care has within the hospital context, but most important still, of the nurse’s direct presence in the very act of caring. In this sense, nursing care is essential because by patients being hospitalized and away from their natural environment this experience can be made even more painful.8) This is why care gains importance during hospitalization because it favors diminished stress and constitutes by itself an important therapeutic effect, given that nurses make use of hospitality, of the art of caring with technical perfection and ethical commitment, to respect and encourage caring for the vulnerable person.9 Hospitals are uncertain worlds where care is invisible and it cannot be counted,10) which is why it is expected that to care we can comprehend the meanings people give to the experience of being ill and hospitalized and the feelings this causes them. Hence, the art of caring is intentional and implies that nurses have the intention of caring and not only carrying out the act of presence and performing some functions. What is really incomprehensible is that nurses care quite well for patients and at the same time not care for the persons.11

Although the results of the investigation show how nurses participate actively in care, they acquires some indirect traits of care, given that they only become interlocutors of care, absorbed by the rest of the administrative and management functions assigned to them in the institutions. This is how other authors have reported it (12, finding that nurses in the care they provide in hospital services recognize what they call the intrinsic factor - internal call to recognizing the profession; even more than the external factor - limitations of the current social, political, and economic contexts, which are intercommunicated, and a category of praxis that goes beyond the physical care and which involves the integration of scientific and empirical nursing knowledge for its recognition. This agrees, in turn, with the findings in our study in the sense that the participating nurses recognize that their priority is to provide care, however, they receive pressure from an institution that obligates them to dedicate their time to other activities that end up taking them away from the patient.

The results also revealed that nurses endured a transformation in their daily work, which contrasts the duty of direct and integral care versus the delegated management functions they have to conduct. This finding is similar to that found by other authors13) who emphasize that hospital institutions have reduced the human to the biological, moving the work of nurses away from their humanist and holistic vision of care with little support from the institutions to provide care, which is why some actions remain relegated, like effective communication and the close interaction with patients and families. All this makes it difficult for nurses to care due to the amount of roles, tasks, and responsibilities the institutional economy and policies have delegated to them (14 and which in this study reported on the problem of job dissatisfaction.

The results also indicated that nurses are multifaceted and carry out multiple tasks delegated to solve situations that emerge in the hospital and with patients; this finding coincides with that of another study15 that states that the nurse’s world implies being attentive to everything occurring simultaneously in the space assigned to their responsibility, doing everything for the patients and not with them, given that they seek their benefit, even if they know they could have as consequence becoming invisible to the patients and their families. Agreeing with the results of this investigation with respect to the transformation of the caregiver role, nurses face the “double agency” care by caring;16 care for people, caring to spend the least amount of resources possible to ensure business sustainability, good indicators, and service quality. Nevertheless, for the nurses participating in this study, the change of role is not presented critically, given that although they should be providing more direct care and performing less administrative activities, it is not possible to dispense with the latter because they redound to the quality of care, and end up making the nurse’s care invisible; a paradoxical situation already alerted by other authors,17 and which has been explained with little representation from nursing in organizations where primacy is given to medical recognition.18

Another finding in the investigation is to highlight how nurses in their daily work are transformed as consequence of a disjunctive of the exercise of a free profession, autonomous in its decisions and regulated by law and institutions. Although they are the majority personnel in health care, nurses are largely invisibles; patients do not recognize if the individual providing care is or is not a nurse, and that invisibility is given essentially by the hierarchical structure of the organizations, the authority of the physicians, hospital policies, and threats of disciplinary actions.19) The aforementioned contrasts with results from the work in which nurse participants believe patients recognize them, but due to aspects different from care and end up identifying them by the uniform or any symbol in them and for being the person that resolves situations that arise and not for the closeness they have with them or for resolving their primary needs, which, according to the nurses, would be ideal for patients, but which in reality are exerted by the nursing aides. It is in this sense that another author20 states that the interest of nurses is to satisfy others, focused on the requirements and needs of institutions; a fact that was verified in this study when the participants expressed not having the autonomy to defend their priorities.

Furthermore, it was found that the power exerted over nurses transforms their role in the hospitalization services and conditions the effect on how they provide care. The aforementioned could be explained by the punitive power of the health institutions when whatever they wish is not carried out, or the power of reward that provides rewards to actions when whatever they desire is done and their actions favor economic gain,19 which brings as a result the transformation of the role in the eagerness to compete for greater institutional benefits or, even, to not lose their jobs. Additionally, the results show that their image has been distorted with the evolution of the contexts in which they provide care, given that they have modified their role and that image they were bringing from the past in which service for another, the devotion, vocation, and sacrifice that made them better nurses has been distorted. In contrast, the only thing this image has achieved is to victimize nurses and, with it, care, given that the idea of “guardian angel” is not precisely the contemporary portrait of what the profession needs, and it is necessary to step away from the script of virtue to approach an identity based on knowledge, autonomy, and empowerment to obtain free and direct exercise for people and the families.21 This way, the transformation of the nurse’s role causes conflicts because of the lack of recognition of their work, a product of not being heard or seen positively, when what they need is to feel with power in decisions for caring of patients.19

Agreeing with the results mentioned, when the nurse’s role is transformed, confusion is produced in their daily work with other participants from the health staff, especially with the nursing aides, given that patients and their relatives think that nursing professionals solve problems but do not care for them, making it necessary for nurses to start identifying themselves through “verbal and non-verbal insignia”22 to mitigate the issue of professional invisibility or the confusion of roles.

Regarding the results obtained, the participants account for the dissatisfaction and lack of motivation the nurses suffer because they cannot practice the role they learnt during their formation with the current context for the autonomous exercise of the profession.23 In this sense, their job dissatisfaction in the hospitalization services is associated to difficulties in their interpersonal relation with coworkers, incoherence between their formation and the job demands, work monotony, and work pressure.24 Finally, they have had to adapt to caring amid a context of an economic model of health services that changes the relationship of professionals with patients and which makes it difficult to provide care of excellence.24

This study concludes that nurses in hospitalization services feel they care for patients but without being with them. In their daily work, they transformed their caregiver role to adapt to diverse demands from the institutional contexts. If they do what they believe they should do, they are invisible for the institutions, but if they do what is visible for the institutions, care becomes invisible for patients and their relatives. In the search for an equilibrium, nurses in their daily work transform their role to adapt to changes and demands, especially the institutional ones.

Nursing needs to redefine itself as discipline in the clinical practice, assigning more importance to the interaction and direct care of patients and their families, which will permit it to be more visible. In addition, it is fitting for institutions to understand the true functions of the nurse and delegate in another human resource the numerous administrative functions they must perform and which distance them from direct care.

The principal limitation in this study was that because it was a qualitative research questions could arise about its rigorousness and reliability, which is why it has maintained the methodological and ethical rigor necessary to guarantee an adequate collection of information, as well as its analysis. Likewise, another difficulty is related with conducting the interviews and observations in which the presence of the principal researcher could modify the behavior of the subjects and contexts. Lastly, it is important to clarify that the discussion of the findings had to done with studies around the invisibility of nursing care conducted in other countries of distinct contexts and work dynamics different from Colombian nursing.

text in

text in