Introduction

Pregnancy is a life experience and one of the most important events within the vital cycle of the woman and the family during which women develop behaviors and perform care practices for themselves and the unborn child to maintain health, care for their diseases, and conserve their wellbeing and that of their child, according to Muñoz.1 The behaviors and care practices women have during the prenatal stage depend on the social structure and on the ethno-historic and environmental context, that is, on the culture in which they grow and live.2,3 Leininger states that culture was the broadest, most comprehensive, holistic and universal aspect of human beings, and that caring for people should be carried out from a transcultural vision. In this sense, Leininger conceives cultural care as the dual, central, and dominant construct within the theory of Culture Care Diversity and Universality,4 the theorist refers to cultural care as: “The values, beliefs, and structured and known expressions of a cognitive form that aid, support, facilitate, or train people or groups to maintain their health or wellbeing, improve their situation or way of life, prevent disease or confront disabilities or death”.5 From this perspective, this proposal constitutes a humanistic, scientific, and comprehensive alternative in caring for pregnant women, recognizing that it is not exempt from the cultural constructions, where its values, customs and beliefs have direct influence on the care practices and each culture defines them from their particular vision of life to be transmitted from generation to generation and, thus, be perpetuated over time.6

Nursing and other disciplines have studied the care of pregnant women from the meanings and experiences to describe, discover, or explore the practices of cultural care conducted by women during the prenatal stage. However, no research was found that have integrated, synthesized, analyzed, and interpreted the results of primary qualitative studies, upon which emerged the interest of carrying out a Meta-Ethnography on the theme. Knowledge derived from this work will be essential to further understand the care of pregnant women and their families from a transcultural perspective. Likewise, interpretation of caring for pregnant women, from this vision, will support the application of the strategic framework of the Policy of Comprehensive Health Care in Colombia, which recognizes the health problems are generated or enhanced by environmental, social, and cultural conditions,7 which must be considered within the guidelines of the Comprehensive Care Route in Maternal Perinatal Health.8 The objective of this study was to conduct an interpretative synthesis of the qualitative studies on the phenomenon of care from the cultural perspective in women with physiological pregnancy.

Methods

The methodology used was the meta-ethnography developed by Noblit and Hare,9 which permits conducting a combination of results in interpretative manner rather than aggregative, to generate a higher level of analysis that contributes much more than the individual findings of each investigation.The seven traditional phases by Noblit and Hare were followed for the meta-ethnography which overlap and repeat as the synthesis advances; these include:

Phase I: Start of the process.

Interest was established in conducting an interpretative and explicative synthesis of cultural care in women with physiological pregnancy.

Phase II: Decide what is relevant for the initial interest.

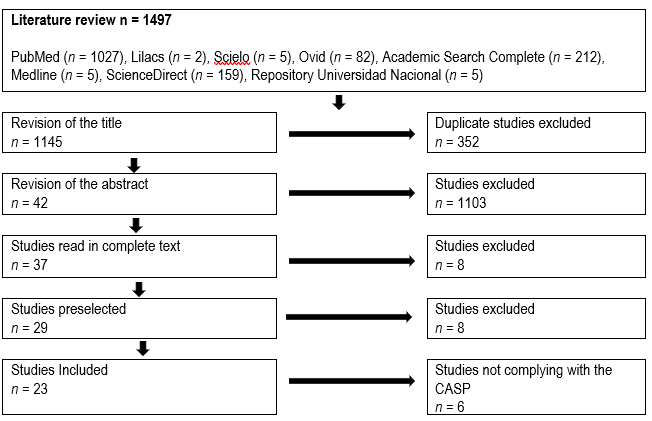

The meta-ethnography included original articles and research works from the Masters in Nursing or other disciplines, which described care from the cultural perspective in women with physiological pregnancy, published in full text, in English, Portuguese, and Spanish between 2000 and 2016. The search strategy used MeSH and DeSH terms “care/cuidado”, “culture/cultura”, “cultural care/cuidado cultural”, “care practices/prácticas de cuidado”, “culturally competent care/cuidado culturalmente competente”, “beliefs/creencias”, “pregnancy/embarazo” y “ethnography/etnografía”. The studies were recovered through a search in PubMed, Lilacs, Scielo, Ovid, Academic Search Complete, Medline Complete, ScienceDirect databases and the Repository at Universidad Nacional in Colombia. Finally, the studies selected were evaluated with the quality criteria from the Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) to assess qualitative studies, 10 which are considered fulfilled if there is internal validity of the study, rigorous analysis of the data, and external validity of the findings.

Phase III: Reading of the studies.

This phase included the reading and rereading of the studies, which permitted extracting the results and conclusions from each of the studies the key metaphors.

Phase IV: Determine how the studies are related.

A list was made of the key metaphors extracted and these were organized to facilitate their comparison, within and between studies.

Phase V: Transfer the studies one within another.

This phase applied the reciprocal translation process among the studies, which consisted in examining the list of the key metaphors in relation to other metaphors within each study. At the end of this phase, it was established that the studies were directly comparable, that is, the key metaphors extracted expressed similarities among the findings of each study.

Phase VI: Synthesize the translations.

The key metaphors were grouped into 12 thematic categories that represented the characteristics or dimensions of cultural care in women with physiological pregnancy. This phase implied new re-readings of the original studies to re-conceptualize the results, that is, the generation of a new interpretation from a second level of analysis.

Phase VII: Express the synthesis in a final product.

This phase consisted in analyzing the interpretations obtained in the synthesis of translations; this again implied reading the studies and the comparison of the 12 thematic categories, which gave way to what Noblit and Hare describe as "line of argument”, which is understood as the construction of a reinterpretation of the findings of the studies. Generation of the line of argument permitted creating a new interpretative synthesis of care from the cultural perspective in women with physiological pregnancy.

Results

The selection process of the articles to be analyzed identified 1497 bibliographic sources from which 21 articles were obtained and two Masters Theses in Nursing were finally included in the Meta-Ethnography, as shown in Figure 1.

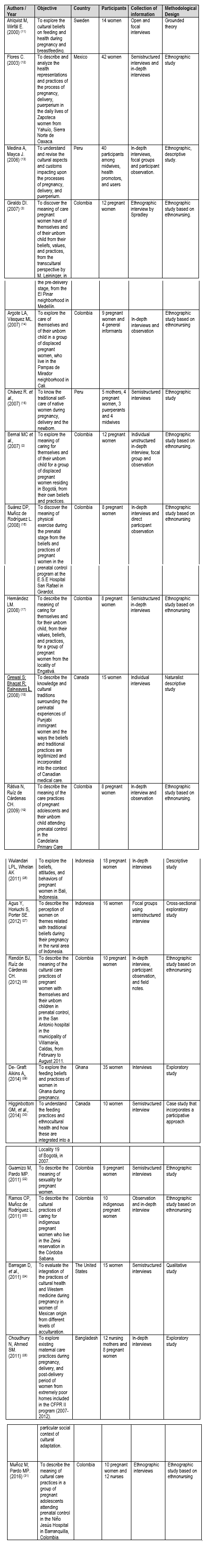

Table 1 shows the objective, form of collecting the information, and methodological design of the studies included in this Meta-ethnography.

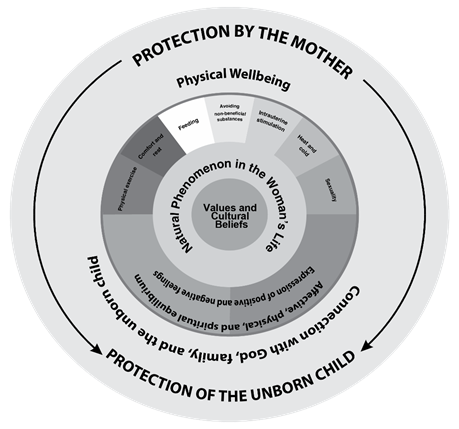

The synthesis of translations among studies permitted identifying 12 thematic categories, which linked together allowed creating a new interpretative synthesis of care from the cultural perspective in women with physiological pregnancy from the line of argument. The thematic categories are: a) pregnancy: a natural phenomenon in the woman’s life; b) spirituality and family support: bond tie with God, the family, and the unborn child; c) the midwife: a symbol of traditional practices during pregnancy; d) Positive and negative feelings: search for emotional balance during pregnancy; e) physical exercise: a way preparing for the delivery moment; f) comfort, rest, and general care: actions aimed at caring for the body of the pregnant woman; g) feeding: a way of preserving the wellbeing of the mother and her unborn child; h) avoid consuming non-beneficial substances: provide protection to the unborn child; i) intrauterine stimulation: strengthens the mother-child affective bond; j) heat and cold: equilibrium in the woman’s body; k) sexuality during pregnancy: interpretations by the woman; l) traditional beliefs and myths: a different way of caring herself during pregnancy Figure 2.

Figure 2 Line of argument: “care from the cultural perspective aimed at the protection of the mother and her unborn child”

Care from the cultural perspective of the pregnant woman, as construct generated in this research proposes that pregnancy is conceived as a natural phenomenon in the woman’s life and the family, is part of the social and biological dimension and from the woman’s vision it develops as an event that requires behaviors and care practices to favor the evolution of the pregnancy, prepare for the delivery, and safeguard the wellbeing of the unborn child.12,14,22,25,27 In these practices, it is important to indicate the articulation among the categories of spirituality and family support: bond tie with God, the family, and the unborn child; and the midwife: a symbol of traditional practices during pregnancy. The family,14,26,28,30,31 the spouse,25,26,30 women in the family,3,14,31 the midwife for some cultures12,14,15,23,28 and the bond with a superior being 3,26,27,28,31 with that related with physical, affective, economic, and spiritual care, which influences positively on the pregnancy.3,14,23,31

Regarding family support, it should be noted that the spouse and other family members are particularly interested in the pregnant woman, desiring the woman and the child have a pregnancy in the best possible conditions.14,25,26,28,30,31 For this, the role of the women in the family is highlighted, especially that of the mother, who as caregiver and, above all as transmitter of beliefs and care practices, has the experience and knowledge to advice women during pregnancy.3,14,23,31 The representation of the midwife is a symbol of service and of traditional practices that represent the care of the pregnant woman; these are granted recognition, merit, acceptance, and credibility by the women and their families, by being in charge of the control and care for the woman during pregnancy and delivery.14,15,23,27

It is evident that women during pregnancy act by following their beliefs and traditional practices and advice from the family, but finally the results of the pregnancy “are in hands of God”.3,27,31 From this perspective, spirituality is an internal guide that provides strength, sense, and significance to the life of the pregnant woman and creates spiritual unity with a supreme being in which the family is involved, seeking to entrust Him with the protection and maintenance of the health of the mother and her unborn child.28,31 Support from the family, from women in the community or midwives, as well as having a spiritual guide during pregnancy favors the expression of feelings. Women seek to maintain an emotional balance that leads them to avoid or stay away from situations that generate negative feelings, like sadness, anger, or distress,3,14 thus, permitting them to care for their own wellbeing and that of their children with the expression of positive feelings that generate in them tranquility, happiness, and desires to go forth.3 Just like pregnant women are aware of the need and importance of emotional care, they also develop activities aimed at caring for and preparing their bodies for a quick delivery and without complications to them and the unborn child.3 Around this goal, care actions are deployed, among them, physical exercise: a way of preparing for the delivery. This is a practice that includes everything related with the body of the future mother, like walking, adopting different positions, and performing some bodily movements, that is, activities that can favor the future mother and avoiding others that cause them harm, to protect themselves during pregnancy and prepare for the delivery.3,14,16,17,19,31

For pregnant women, comfort, rest and general care are practices aimed at caring for their bodies,3,18,19,23,28,31 which help them to avoid infections, abortions, premature deliveries, risk of falls, mistreatment to the babies and the children being born with physical defects.18,23,31 In the search for maternal health protection, pregnant women consider feeding: a way of preserving the wellbeing of the mother and of her unborn child, and it is achieved through a feeding change and beneficial practices, like eating well.2,3,11-13,17,19-23,25-28,30,31 The women include in their eating the consumption "soft foods” or “healthy foods”; among them, vegetables, fruits, meat, chicken, fish, milk and its derivates, which are recognized as foods that serve to gain weight, strengthen the body by avoiding the threat of abortion, preventing anemia, ensuring physical strength, minimizing the physiological effects of the pregnancy, maximizing the baby’s health, and preparing for the delivery;3,18-21,29-31 and restriction of “strong foods " which could be interpreted as harmful, "heavy", capable of causing harm to the body, such as junk food, snacks and industrialized foods, among others, seen as forbidden during pregnancy.3,20,21,29-31 Around feeding, rituals also exist aimed at guaranteeing in the mother “to have a good delivery”, from consuming foods that “provide strength”, like foods with salt and bienestarina (vegetable flour, added with powdered skimmed milk, enriched with vitamins and minerals); food to “open the flesh” (onion); ingesting hot beverages (cinnamon and castor oil) “favor labor contraction pain”;3 consuming butter in each meal and drinking abundant liquid facilitate expulsing the fetus.30

Women consider avoiding the consumption of non-beneficial substances as a way of generating protection to themselves and to the unborn child, recognizing that substances, like alcohol, cigarretes, psychoactive substances and medications are harmful to them and to the child because they are associated with negative effects in the short and long term in the health of the infants.13,14,19,21,22,24

Intrauterine stimulation: enhances the mother-child affective bond by expressing love and affection with the hope of delivering a happy baby, which develops emotionally, mentally, and socially; generating a human being who is more critical, adaptable, and endowed with emotional intelligence; besides giving the mother the opportunity to reflect on the new role she will soon acquire.3,19,28,31

Heat and cold: balance in the woman’s body. Cold is considered an enemy that must be fought in as much as possible through heat.3,28 Cold can enter the woman’s body through different ways and become a threat to the mother and the unborn child.3,23,31 This leads them to developing a series of practices that let them keep their body in equilibrium between cold and heat and which guarantees them, from their traditional knowledge, to remain well during pregnancy, guarantee the health of the fetus and restore the mother’s health after the delivery.3,14,23 In synthesis, cold behaves as a sensation they do not like, they feel that what their body presents is not good and is unpleasant.3

Sexuality during pregnancy: interpretations by the woman. For the pregnant woman, the fact of engaging in sexuality, relating with her partner, and being well are cultural domains with which they identify sexuality in this stage of life.22 However, fear exists upon practicing the sexuality: hurting or causing physical defects in the fetus, precipitating the moment of delivery,22,23 and the presence of physical changes during pregnancy altering the image and self-concept, so that sexuality is reduced to the enjoyment of a sexual encounter by the couple without affective feelings.22

Traditional beliefs and myths as a different way of caring for themselves in the pregnancy; during pregnancy, women stick to diverse customs, myths, and beliefs, which are founded, developed, transmitted, and maintained through knowledge and the experience of a social group social and from a family context in which the pregnant woman is immersed.28 This is how beliefs are reported related with certain restrictions and mobility during a lunar or solar eclipse,24,25 attending funerals, weddings26 and cemeteries,25 as a way of protecting themselves, preventing deformities in the unborn child, and avoiding disease.28

Discussion

The Meta-ethnography permitted, from first-order interpretations (points of view expressed by the participants of the studies) and second-order interpretations (interpretations reported by the authors of the studies), developing a line of argument (third-order interpretation)32 that exposes in greater depth existing knowledge on care the women carry out from the cultural context during the prenatal stage. The line of argument links 12 thematic categories, one of them highlights how the pregnancy, in spite of being conceived as a natural phenomenon in the woman’s life,12,14,22,25,27 is a process defined by the social, historical, and cultural contexts that demands in her two important components in caring for herself and her unborn child. The first, is to be prepared psychologically, emotionally, and spiritually.33 In this sense, the following categories are described: spirituality3,26-28,31 and family support:2,3,14,25,26,28,30,31a bond tie with God, the family and the unborn child, and the midwife: a symbol of traditional practices during pregnancy.12,14,15,23,28 Family support, women from the community, and the connection with a supreme being during the pregnancy, permit in the woman an affective, economic, and spiritual equilibrium,3,14,23,31 which leads her to stay away from situations that generate negative feelings,3,14 thus, permitting the care of their own emotional wellbeing with the expression of positive feelings that generate in them tranquility and happiness during the pregnancy.3

The second component corresponds to the physical preparation, which implies the change of behaviors and habits aimed at the health of the mother and that of the unborn child.33 This process links seven categories, the practice of physical exercise;3,14,16,19,28,31comfort, rest, and general care;3,18,19,23,28,31feeding: a way of preserving the mother’s wellbeing and that of her unborn child;3,12,13,17,19,20,21,23,25-28,30,31avoiding the intake of non-beneficial substances;13,14,19,21,22,24intrauterine stimulation: strengthens the mother-child affective bond;3,19,28,31heat and cold: equilibrium in the woman’s body;3,14,23,28,31sexuality during pregnancy: interpretations by the woman.22,23 The behaviors and care practices mentioned are framed within a strong system of traditional beliefs, customs and myths24-26,28 that constitute a cultural dimension, which persists, is transmitted through tradition and is part of the reality of the pregnant women to care for their own health and that of their unborn children.28

According to the Theory of Culture Care Diversity and Universality, by Madeleine Leininger, the findings of this research evidence how caring for the woman during the prenatal stage, in each country, is a cultural phenomenon with differences and similarities in its meanings, values, beliefs, life styles, and care practices in the pregnant woman and social and family nucleus. From this principle, the goal of the theory of cultural care, according to Leininger, is to offer care synthesized within Universality (shared or similar characteristics of cultural care) and Diversity (differences or variations of cultural care), so that it can be culturally congruent, safe, beneficial, and significant,4 aimed at the protection of the mother and her unborn child.

Limitations of this study.

The meta-ethnography is a qualitative methodology constituted by seven phases which overlap and repeat as the interpretative synthesis advances. However, no guide exists to clearly transmit the methodology, analysis and synthesis of the reinterpretation of the findings, which becomes an important barrier to the base of the scientific evidence that permits evaluating the methodological rigor, credibility, and reliability of the findings of a meta-ethnography. It is possible that all the studies published on caring for pregnant women from the cultural perspective have not been included in this synthesis, although a complete and extensive search was conducted in Spanish, English, and Portuguese in seven databases and the repository at Universidad Nacional de Colombia.

Conclusion

The line of argument reflects how behaviors and care practices of pregnant women are aimed at guaranteeing their protection and that of their unborn children. These care practices are configured from knowledge, values, beliefs, and customs, that is, the culture in which the women are born, grow up, and develop. Consequently, care from the cultural perspective in women with physiological pregnancy is a construct that must be understood from the meanings, experiences, and cultural context surrounding the woman’s family, social, and spiritual structure during pregnancy. This interpretative synthesis reflects the need to offer culturally congruent care by the health staff in charge of maternal perinatal care to achieve a dual construct between generic knowledge (emic) and professional knowledge (ethical), which permits their planning and effectively applying care actions adapted to the beliefs of health or disease, values and practices of the pregnant woman and her family, and which helps the pregnant woman to maintain or reach full physical, mental, social, and spiritual wellbeing.

text in

text in