The leishmaniases are diseases caused by obligate intracellular protozoans of the genus Leishmania. The geographical distribution of leishmaniasis is limited by the distribution of the vectors, and the wild and domestic animals that serve as reservoirs for the parasites (Rotureau, 2006). Although L. (Leishmania) infantum has been relatively well characterized as the etiological agent for visceral leishmaniasis in multiple areas, the species responsible for the cutaneous form of the disease remains unknown in many Colombian foci, whereas the existing distribution records come from the characterization of a very limited number of human isolates (Martinez et al., 2010; Salgado-Almario et al., 2019). Studies carried out to date have established that L. (V.) braziliensis Vianna, 1911 and L. (V.) panamensis Laison and Shaw, 1972 have the broadest distribution throughout the country, while L. (L.) mexicana Biagi, 1953 is present in all geographical regions of Colombia with the exception of the Caribbean plain.

Other species exhibit limited distribution; L. (L.) amazonensis Lainson and Shaw, 1972 has been reported in the departments of Antioquia, Chocó, Meta, Norte de Santander, Tolima, and Santander, L. (V.) lainsoni Silveira, Shaw, Braga and Ishikawa, 1987 was reported in Antioquia and Putumayo, L. (V.) colombiensis Kreutzer et al. 1991 was found in Santander, and L. (V.) equatoriensis Grimaldi et al. 1992 in Antioquia (Corredor et al., 1989; Gore Saravia et al., 2002; Ovalle et al., 2006; Ramirez et al., 2016). On the other hand, L. (V.) guyanensis Floch, 1954 was originally recorded in the Orinoco and Amazon river basins (Corredor et al., 1989). However, over the last decade has also been reported in the departments of Tolima, Valle del Cauca, and Sucre (Rodriguez-Barraquer et al., 2008; Figueroa et al., 2009; Martinez et al., 2010), outside of what was traditionally considered to be the natural focus of transmission of this species. Here, we report the presence of L. (V.) guyanensis in rural area of Buenaventura, on the Colombian Pacific coast. This provides further evidence for a more extensive geographical distribution of L. (V.) guyanensis in Colombia.

Clinical samples were obtained in January 2011 from a 29 year-old male from Bajo Calima, a village within the municipality of Buenaventura, in the department of Valle del Cauca, Colombia. The autochthonous nature of the infection was determined by an epidemiological survey, in which sociodemographic aspects and sites visited during the three months before diagnosis were analyzed. The patient presented a distinct ulcer with raised borders on his neck, which had appeared approximately a month earlier according to the information provided by the patient. The patient was examined at Laboratorio de Salud Pública at Departamento Administrativo de Seguridad Social en Salud de Sucre (DASSSALUD) during a short visit to the city of Sincelejo, in the department of Sucre. Samples from the lesion were taken for parasite culture and molecular genotyping of the infective species. Samples for parasite culture were taken by aspiration biopsy from the ulcer with a fine needle. Macerated tissue was inoculated into Novy-Nicolle-MacNeal (NNN) culture medium (Walton et al., 1977), and incubated at 26 °C. The culture was examined daily during four weeks to detect the flagellate forms of the parasite.

A clinical sample for species identification was obtained by scraping the border of the lesion with a scalpel. This material was deposited in 1.5 mL microtubes containing 0.5 mL of lysis buffer (Tris-HCl [10mM], EDTA [10mM] and SDS [10mM]). Genomic DNA extraction was performed as described previously using a salting out procedure (Martinez et al., 2010). For identification of the parasite species, a fragment of 866 bp of the Cytochrome b gene of Leishmania was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with primer pair Lcyt-S (5'-GGT GTA GGT TTT AGT YTA GG-3') and Lcyt-R (5'-CTA CAA TAA ACA AAT CAT AAT ATR CAA TT-3') (Kato et al., 2007). The amplicon of the expected size was purified and directly sequenced on both strands of DNA with these primers.

The sequences obtained were edited using MEGA 5.22 software (Tamura et al., 2011), in order to generate a consensus sequence. This consensus sequence was subjected to a preliminary analysis of similarity against sequences available in GenBank using BLASTn (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) (Altschul et al., 1990). Multiple alignments were carried out with the Clustal W software (Thompson et al., 1994) incorporated in MEGA 5.22. The sequences of other clinical isolates of Leishmania from Colombia (Martínez et al., 2010), as well as those of L. (V.) guyanensis reference strains available in GenBank (LC153220, LC153193), were analyzed together with the sequence obtained from the patient sample. The genetic relationships within this group of sequences were inferred by the Maximum Parsimony method in MEGA 5.22 program using the Subtree-Pruning-Regrafting (SPR) algorithm and a thousand bootstrap were performed to assess branch support (Felsenstein, 1985; Tamura et al., 2011). The patient participated voluntarily and provided written informed consent.

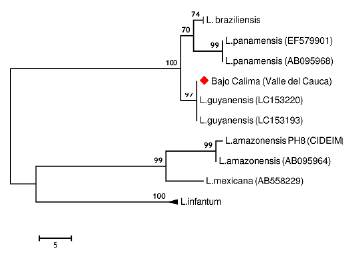

Direct parasitological examination of dermal scrapings revealed the presence of Leishmania amastigotes. The parasite was identified as L. (V.) guyanensis by the analysis of the Cytochrome b gene. The characteristic nucleotide polymorphisms of L. (V.) guyanensis described by Martínez et al. (2010) were observed within the nucleotide sequence of the Cytochrome b fragment amplified from the sample from Bajo Calima. This allowed distinguishing this species from other Leishmania (Viannia) species that may be found at this region. In the phylogenetic tree the sample from Bajo Calima clustered with high confidence (bootstrap 97 %) with the reference strains sequences of L. (V.) guyanensis (Fig. 1). On the other hand, parasite culture was considered to be negative after four weeks follow-up, during which no promastigotes were observed.

Figure 1 Most parsimonious tree (lenght=101 steps, consistency index= 0.949495, retention index= 0.983713) of the Cytochrome b partial sequences from Leishmania species. The analysis involved 18 nucleotide sequences and a total of 509 positions in the final dataset. Numbers above each branch represents the bootstrap support and the red diamond denotes the sample from Bajo Calima, Buenaventura

This study records the presence of L. (V.) guyanensis in a patient from Bajo Calima, in the department of Valle del Cauca, on the Pacific Coast of Colombia. In this region L. (V.)panamensis has been widely recognized as the main causal agent of leishmaniasis (Gore Saravia et al., 2002). Figueroa et al. (2009) previously reported the isolation of L. (V.) guyanensis from two patients with cutaneous leishmaniasis in Guacari and Vijes municipalities on the Andean region of Valle del Cauca. The Vijes leishmaniasis focus is best known for the presence of L. (V.) panamensis, which has been isolated from humans and the sloth Choloepus hoffmanni (Loyola et al., 1988), and L. (V.) braziliensis, which has been isolated from dogs (Travi et al., 2006).

Although in Brazil and BoliviaL. (V.)guyanensis is associated with both cutaneous and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis, in Colombia this parasite has been found to be associated mainly with cutaneous leishmaniasis. One possible hypothesis is that parasite strains circulating in Colombia lack the virulence factors that characterize metastatic L. (V.) guyanensis parasites from those countries where mucocutaneous manifestations in patients are frequent. Additionally, it is also possible that the genetic background or other intrinsic factors related to human population may play a role in the appearance of the mucocutaneous form of the disease.

Until the past few years, L. (V.) guyanensis was reported mainly in the Amazon and Orinoquia regions of the country (Grimaldi et al., 1989). The finding of this species in both the Andean and Caribbean regions (Rodriguez-Barraquer et al., 2008; Martinez et al., 2010; Hernández et al., 2014), together with this record from the Pacific Coast, supports the existence of wider scenarios for L. (V.) guyanensis transmission cycles in Colombia. Those changes in the geographical distribution of L. (V.) guyanensis could be attributed to forced displacement of human populations by the internal conflict, and perhaps due to the migration of reservoirs, or the appearance of new epidemiological actors (Martínez et al., 2010; Ferro et al., 2011). In Colombia, only two sand fly species have been found infected with L. (V.) guyanensis, i.e., Lutzomyia umbratilis Ward and Fraiha, 1977 (Nyssomyia subgenus) in the department of Amazonas, and Lutzomyia longiflocosa Osorno-Mesa, Morales, Osorno and Muñoz, 1970 (Verrucarum group) in the department of Tolima (Young et al., 1987; Ferro et al., 2011). However, to date, there are no reports of these sand fly species in the Colombian Pacific region. Therefore, ecoepidemiological studies are required to incriminate the vector of this parasite in the region since we cannot rule out the role of other phlebotomine sand fly species, including those from Nyssomyia subgenus or the Verrucarum group. Regarding the potential reservoirs, in addition to humans, canines and cotton rats are the vertebrates found infected with L. (V.) guyanensis in this country (Vásquez-Trujillo et al., 2008; Santaella et al., 2011; Ocampo et al., 2012). Among these, it has been suggested that canines could act as reservoirs for this parasite, but their infective capacity to sandflies has not been proven so far.

Furthermore, the establishment of transmission cycles in new areas may have been facilitated by the presence of other phlebotomine sand fly species already known to be vectors of Leishmania parasites. Although this could explain epidemic outbreaks of the disease (Rodríguez-Barraquer et al., 2008), the distribution of L. (V.)guyanensis in the country may also be wider than previously assumed, since the Leishmania species involved in vast majority of cases of leishmaniasis are not usually typed. Furthermore, there is a possibility that isolates of L. (V.) guyanensis have been mistyped or misidentified as L. (V.) panamensis, given the close genetic relationship between these two species, thus contributing to the underestimation of the former's geographical distribution in the country. In conclusion, the presence of L. (V.)guyanensis in the Colombian Pacific region has been confirmed, which demonstrates the expansion of the geographical distribution of this parasite species in Colombia, and reveals the complexity of the transmission cycle in this area of the country, where other Leishmania spp. also circulate.