Toucans (family Ramphastidae) are large birds that nourish themselves primarily on the fruits of a wide variety of plants. It is possible that one single species, for example, can consume more than 115 types of fruit. Yet toucans are also omnivorous, often capturing insects and other food sources for their chicks (Short and Horne, 2002). In general, these species require very high levels of protein in their diet (Remsen et al., 1993). Several genera, including Ramphastos, are known to hunt small mammals, birds, frogs, and even snakes (Short and Horne, 2002).

Some species have been registered as nest robbers and predators of eggs and offspring as well. Species such as the toucanet (Aulacorhynchus sp.) and aracari (Pteroglossus sp.) are regular nest predators of species of the Icteridae, Fringillidae, and Hirundinidae families (Short and Horne, 2002). Larger toucans, such as the black-mandibled toucan (Ramphastos ambiguous Swainson, 1823) have been known to rob the nests of tyrant flycatcher species Pitangus, Myiozetetes, and Megarhynchus (Short and Horne, 2002); the green-billed toucan, the smallest of the genus, also hunts eggs and offspring of Pitangus sulphuratus (Linnaeus, 1766) and Passer domesticus (Linnaeus, 1758) (Leite et al., 2010). In general, several species of birds view toucans as potential predators. For this reason, these birds make displays of mobbing (Short and Horne, 2002), intending to force the predator to give up its pursuit and continue on its way (Zuberbühler, 2009). This study aims to describe the failure of the anti-predatory strategy and the predation of Turdus leucomelas (Vieillot, 1818) eggs by Ramphastos vitellinus ariel (Vigors, 1826) at the Botanical Garden of Rio de Janeiro, RJ.

Observations were made during birdwatching in the Botanical Garden of Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil. Specifically, the arboretum of the Botanical Garden is located in the city of Rio de Janeiro (22° 58' 14'' S and 43° 13' 18 '' W), occupying an area of 54 hectares, crossed by the Rio dos Macacos, which supplies the lakes, canals, and channels of the entire floristic park, with alluvial, dystrophic and eutrophic soils and a humid and rainy tropical climate (Castro and Pinheiro, 2001). The observations were made with 7 x 35 binoculars and digital song recordings were made at a sampling rate of 48 kHz and 16 bits per sample using a Tascam DR-07 Mk II recorder. Spectrograms of all songs were generated and measured using Raven Pro 1.5 (Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA; window type: Hamming; size: 14.6 ms; filter bandwidth: 88.9 Hz; overlap: 80 %; DFT size: 2048 samples).

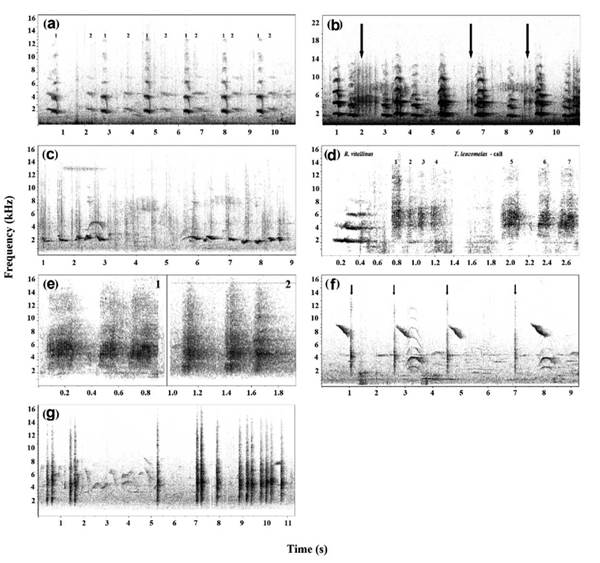

On September 2, 2012, at the Botanical Garden ofRio de Janeiro, I observed three adult individuals of R. vitellinus ariel, two of which were observed making calls, apparently not in a duet, at 10:57 (Fig.1a). Subsequently, the two individuals flew to another tree where they continued their vocalizations, and this act was repeated many times. Later, I observed an individual flying from the same tree. At that moment, the individual was attacked by an individual of the species T. leucomelas. The attack was made in a swooping flight over the predator's head during the continuous emissions of calls of "bullying", mobbing or persecution. The individual, intimidated, was forced to fly to a different, more distant tree, and was again attacked during flight. Minutes later, the predator returned to the same tree (next to the tree where the nest was located) and one of the T. leucomelas individuals vocalized alarm calls at 10:59 (Fig.1b). These calls are characterized by having a higher bandwidth (x̅ = 2293.4; n = 6), higher low frequency (x̅ = 4024; n = 6) and higher high frequency (x̅= 6317.4; n = 6) than the normal song (Figure 1c; bandwidth x̅ = 1317; low freq x̅ = 1711.9; high freq x̅ = 3028.8; n = 3) and are composed of a single pitch emitted in a repetitive rhythm (Fig.1b).

Figure 1 Birdsong spectrograms of predator Ariel toucan and persecution behavior and alarm calls of the pale-breasted thrush. a: Songs made by two Ariel toucan individuals (the songs of each individual are differentiated by numbers - XC109772); b: Alarm calls made by the pale-breasted thrush mixed with the calls of the Ariel toucan (the arrows indicate the thrush's calls - XC550111); c: Two different songs repertories of the pale-breasted thrush in the same location (XC550114); d: Calls made by the Ariel toucan and a set of persecution calls of the thrush (XC550117); e: Comparison of the persecution calls (1) and alarm calls (2) (XC550120); f: (XC550129) and g: (XC550128): Alarm calls made by the pale-breasted thrush when the predator is far away (the arrows indicate the thrush's calls, which are mixed with other birds' calls). (The catalogue numbers of each described vocalization are reported with the hyperlinks linked directly to the Xeno - canto database).

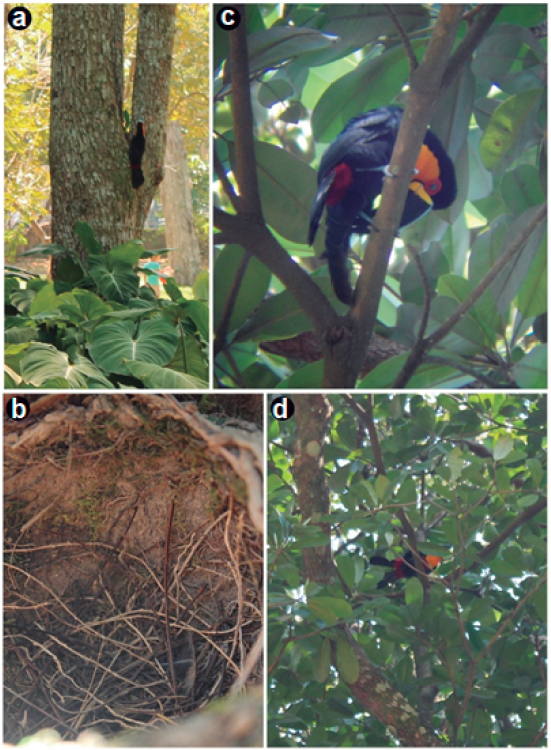

The predator landed on the tree trunk almost in front of the nest (Fig. 2a), which was located inside a small hole between the trunk and a lateral branch, approximately two meters from the ground. An individual of T. leucomelas attacked the predator and vocalized its mobbing call at 11:01 (Fig.1d; bandwidth x̅ = 3035; low freq x̅ = 4234.3; high freq x̅ = 7269.6; n = 7). This particular call, in contrast to the alarm call, is very fast and short, with several pitches in the same call, with maximum frequencies increasing and then decreasing (mobbing call: delta time x̅ = 0.11; # pitch = 5.6; n = 7 vs alarm call: delta time x̅ = 422.9; # pitch = 4.5; n = 6). In general, this call is emitted with higher frequency, higher bandwidth and higher frequency peaks (Fig. 1e; mobbing call: peak freq x = 5484.4; n = 7 vs alarm call: peak freq x̅ = 5148,4; n = 6). Next, a second individual exited the nest. The toucan retrieved the egg and flew to a nearby tree, where it rose to beneath the canopy to eat the egg. Later the toucan exhibited cleaning behavior (Fig. 2c). Shortly after, one of the T. leucomelas individuals returned to the nest to find it empty (Fig. 2b). One of the individuals continued its alarm calls, although these calls were then made with longer intervals between them (Fig. 1f at 11:08; bandwidth x̅ = 2186.2; low freq x̅ = 3883.6; high freq: x̅ = 6069.9; peak freq x̅ = 5200.2; delta time = 162.6; # pitch = 1,88; n = 8. Figure 1G at 11:22; bandwidth x̅ = 2757.1; low freq x̅ = 2884.6; high freq x̅ = 5641.7; peak freq x̅ = 4664.1; delta time = 0,19; # pitch = 1; n = 4). After approximately five minutes, the toucan that captured the egg approached another individual of the same species that was positioned on a branch at the extreme opposite of the tree. Then, it exhibited courting behavior (affectionately patting the reproductive partner) and engaged in a reproductive coupling that lasted for about 13 seconds (Fig. 2d).

Figure 2 a Ariel toucan before robbing the egg, with the pale-breasted thrush's nest in front, located between the tree trunk and a lateral branch; b Empty pale-breasted thrush's nest after the predation; c Cleaning behavior of the Ariel toucan after feeding on the thrush's egg; d Reproductive coupling of two Ariel toucan individuals.

In this observation, I registered that the T. leucomelas utilized two different vocalizing strategies: 1) the alarm call, which serves the purpose of alerting as to the presence and location of the predator and possibly to generate confusion, which benefits the individual being called (Zuberbühler, 2009); and 2) the call of persecution accompanied by agonistic flight, which is intended to deter the predator (Zuberbühler, 2009). The calls of alert with high frequencies corroborate the reports for several songbirds, principally when they are threatened by birds of prey. It is believed that these calls are difficult to locate and may decrease the predators' motivation (Marler, 1955; Jurisevic and Sanderson, 1998; Jones and Hill, 2001). Observing the spectrograms of the alarm calls (Fig. 1b,1f), it is possible to deduce that the calling rate could be related to the proximity of the predator, and therefore could offer information as to the predatory risk or danger, as occurs in other species (Templeton et al., 2005; Griesser, 2009; Suzuki, 2014; Dutour et al., 2016; Carlson et al.,2017), even these calls can warn other species of the presence of a potential nest predator (Dutour et al., 2016; Dutour et al., 2019; Policht et al., 2019; Carlson et al., 2020). In this behavioral report, I conclude that the anti-predatory strategy of T. leucomelas was not successful in avoiding the predation of its nest by R. vitellinus. Despite the efforts to attack the predator and employing two different vocalization strategies (alarm calls and intimidation calls), the size and weight of the predator (46-56 cm and 285-455 g according to Short and Horne (2002)) far surpass those of the thrush (23-27 cm and 47-78 g according to Collar (2005)). Initially, the strategies were able to intimate the predator; however, the predator was then able to assess the situation either based on a possible interaction with the thrush or previous experiences and understood that it was not a dangerous situation. It is known that various species of the Ramphastos genus are usually attacked by species of the Tyrannidae family, including cases of being chased by the Double-toothed kite (Harpagus bidentatus Latham, 1790); therefore, the behavior observed is typical of this species, which may use other strategies to be more effective in the predation of nests. These anti-predatory strategies are employed by various bird species, but not all cases are effective. In a semi-open plantation in Ecuador, were observed 14 distinct species attacking and calling a predator, including two hummingbird species. Although the number of individuals was high, the strategies have also failed (Matheus et al.,1996). The Ariel toucan, like the other birds of its genus, consumes a wide variety of food types, including fruits, termites, rats, even eggs, and the offspring of other birds (Short and Horne, 2002; da Silva and Schetini, 2012). However, only a few species of birds and other vertebrates have been registered as part of their diet. The effects of predation on the population of this species in its entirety are still unknown, however, as with other species in urban areas, the effect of nest predation by new predators can have a marked impact on reproductive events (Wang and Hung, 2019).