INTRODUCTION

Coral reefs are one of the world's most diverse ecosystems, harboring more than 25 % of marine fish species (Sale, 1980; Moberg and Folke, 1999; Coker et al., 2014), at a level that in some reef systems in the Indo-Pacific Ocean more than 1000 species occur (Tittensor et al., 2010; Kulbicki et al., 2011). For Colombian Caribbean reef systems, up to 500 fish species can be found in some oceanic complexes in the Seaflower Biosphere Reserve (Mejía and Garzón-Ferreira, 2000; Bolaños-Cubillos et al., 2015; Acero et al., 2019) or between 300 to 400 species in coastal reefs in the continental platform (e.g., San Bernardo, Rosario or Santa Marta; Acero and Garzón, 1987).

Despite the importance of these ecosystems in economic, social, and environmental assets, coral reefs have continued to deteriorate due to human impacts such as overfishing, declining water quality (Johnston and Roberts, 2009), and rising ocean temperatures (Hoegh-Guldberg et al., 2007). Despite the discouraging forecast for coral reefs worldwide, and especially for the Caribbean where the hard coral cover has been reduced by 80 % since the 1970's (Gardner et al., 2003), one of the last well-developed coral reefs in the Colombian Caribbean was recently discovered in the bay of Cartagena (López-Victoria et al., 2014). The so-called, Varadero Reef is located in the southern mouth of the bay, where environmental conditions are far away from the optimal for coral growth: water is turbid, polluted, and with high levels of sedimentation due to the constant discharges of the Dique Canal, which drains 7 % of the Magdalena River, the largest lotic system in Colombia (Tosic et al., 2016; Pizarro et al., 2017).

Currently, national plans for dredging the area to create an alternate navigation canal for large cargo ships are being developed (INVIAS, 2015), and this would, directly and indirectly, damage about 50 % of this unusual but well-developed reef, with catastrophic effects on the marine life that thrive in this area. To contribute to the knowledge of the extant fish fauna present in this coral reef, we conducted research during both rainy and dry seasons. The inventory was carried out with different methods. The aim of this study was to assess the reef fish inventory of this unusual reef to serve as a starting point for future investigations, and to create awareness of the richness of organisms and the uniqueness of this ecosystem.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study area

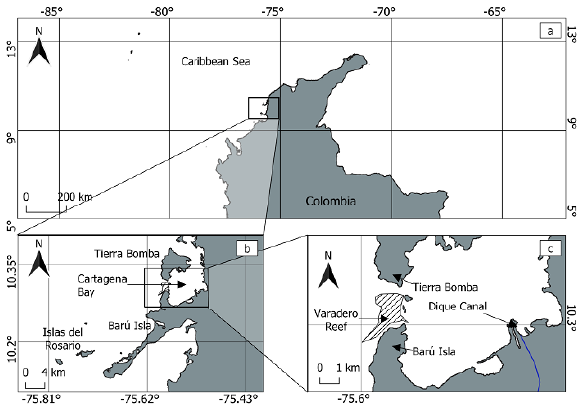

The bay of Cartagena is located in the Colombian continental Caribbean (Fig. 1). Sea surface temperature ranges between 27 and 31 °C, and salinity varies from 6 near the river mouth to 37 outside the bay (Pfaff, 1969; Alonso et al., 2000; Grisales-López et al., 2014). Climate in this region is dominated by two main periods, the dry season from December to April and the rainy season from May to November (Delgadillo-Garzón and Zapata-Ramírez, 2009). This bay receives constant discharges of freshwater, sediments, and sewage water from the Dique Canal, which varies throughout the year in accordance with the seasonal water flow (Leble and Cuignon, 1987; Restrepo et al., 2006). This huge sediment discharge has caused high turbidity and sediment load. In addition to this, deep draft vessel traffic, ship discharges, wastewater dumping by industrial companies, and constant dredging that resuspend heavy metals and other substances that are usually accumulated on the seabed have also caused the decrease in the water quality inside the bay (Aguilera, 2006; Parra et al., 2011; Jaramillo-Colorado et al., 2016; Tosic et al., 2017, 2019).

The Varadero Reef is located 5 km away from the mouth of the canal (Fig. 1). It is part of a large coastal coral formation that begins on the island of Tierra Bomba (Fig. 1) and continues throughout the southern margin of Barú Peninsula. The mean coral formations considered for this study extend over an area of 1.12 km2 between 1.5 and 25 m deep (Pizarro et al., 2017). The area consists of well-developed coral reefs, seagrass platforms, bioturbated sediment patches, and a reef slope that ends at 25-30 m deep. Even with the high turbidity and sediment load (López-Londoño et al., 2021, 2023), the reef has an average of 45 % of live coral cover, with 38 coral species listed. The most common hard coral species are Orbicella flaveolata (Ellis and Solander, 1786), O. annularis (Ellis and Solander, 1786), Agaricia agaricites (Linnaeus, 1758) y A. tenuifolia Dana, 1846 (López-Victoria et al., 2014; Pizarro et al., 2017).

Surveys

The sampling took place from March 2015 to November 2019. Visual censuses were conducted during both dry and wet seasons. In different years, SCUBA divers carried out a total of 61 hours of observation on random dives, 19 hours during the dry season, and 42 hours during the rainy season. Also, 13 videos were recorded at different sites of the reef during March 2019 (dry season). Each camera Fitfort 4k was attached to a PVC tripod and recorded about 5 m2 of the reef for 40 to 60 min (for a total of 5 hours of underwater videos). The videos were then analyzed on a computer. We focused specifically on species richness, due to the different methods and sampling efforts used during the studies, which makes comparisons with reefs in other areas of the Caribbean difficult. In this sense, the species inventory is a starting point for comparative studies over time, especially considering eventual dredging works that would severely alter the reef. The classification of teleost fish species was made according to Betancur et al. (2017) and cartilaginous fishes were classified following Nelson et al. (2016).

RESULTS

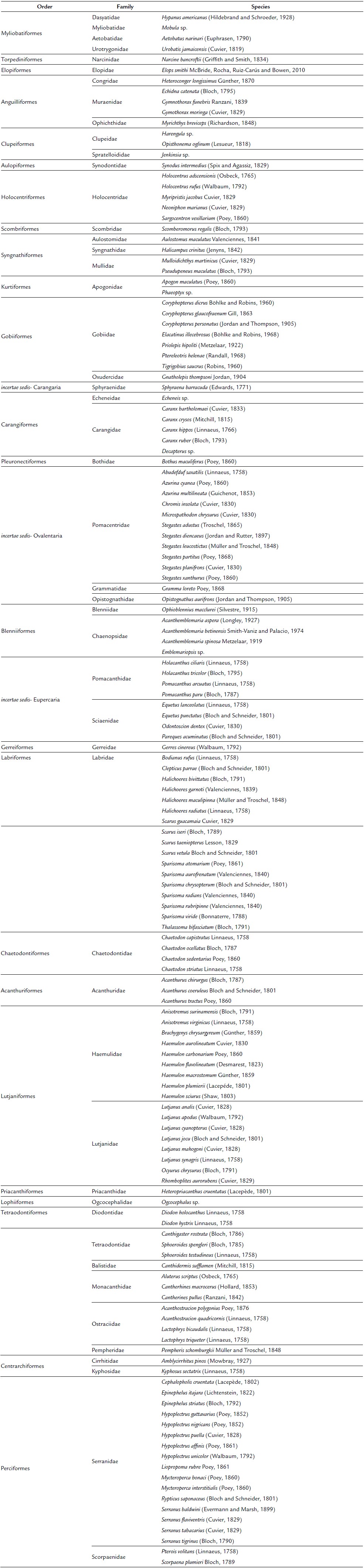

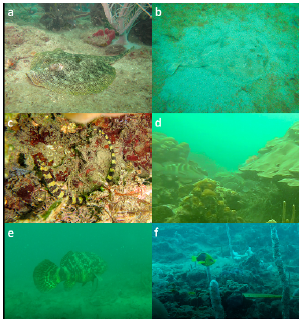

We recorded 147 species from 27 orders and 49 families (Supplemental material: Table 1). The richest families were Labridae, with 17 species (11.6 %), Serranidae with 16 species (10.9 %), and Pomacentridae with 11 species (7.5 %). Seven of the observed species have received national threat status (Chasqui et al., 2017): the Crevalle Jack [Caranx hippos (Linnaeus, 1766)], the Black Grouper [Mycteroperca bonaci (Poey, 1860)], the Mutton Snapper [Lutjanus analis (Cuvier, 1828)] and the Cubera Snapper [ L. cyanopterus (Cuvier, 1828)] are listed as vulnerable (VU); the Rainbow Parrotfish (Scarus guacamaia Cuvier, 1829) is listed as endangered (EN); the Atlantic Goliath Grouper [Epinephelus itajara (Lichtenstein, 1822)] and the Nassau Grouper [ E. striatus (Block, 1792)] are listed as critically endangered (CR). At a global scale, three of these species are also listed by the IUCN as vulnerable VU (L. cyanopterus, Lindeman et al., 2018; E. itajara, Bertoncini et al., 2018) and as critically endangered CR (E. striatus,Sadovy et al., 2018; Fig. 2).

DISCUSSION

Considering the high anthropogenic pressures and the suboptimal water conditions at Varadero Reef (Roitman et al., 2020; López-Londoño et al., 2021, 2023), the species richness found is particularly high when compared to other coral reefs in the Colombian Caribbean. Even though this initial list might not be complete, the 147 species found here, represent more than a quarter of the maximum reached in other coral systems in Colombia, all of them orders of magnitude larger in area than Varadero (among them, those found in the Seaflower Biosphere Reserve, Bolaños et al., 2015; Acero et al., 2019). All the species recorded were found inside an area of about 1 km2, which is the area of the whole well-developed reef that was sampled. To put this value in perspective, the total number of species observed in Islas del Rosario, a protected area nearby with 50 km2 of coral formations, is 270 species (Acero and Garzón, 1985, 1986; Garzón and Acero, 1988; Acero et al., 1994; Mejía et al., 1994; Delgadillo-Garzón and Zapata-Ramírez, 2009).

Figure 2 Some of the fish species found in Varadero: a) Urobatisjamaicensis, b) Narcine bancroftii, c) Micrognathus crinitus, d) Epinephelus striatus, e) E. itajara, f) Hypoplectrusguttavarius (All pictures taken by the authors).

Varadero has more than half the number of fish species found in a coral system almost 50 times bigger in extension. This could be attributed to the fact that it is a shallow water reef, with light conditions equivalent to those of a mesophotic (deep water) reef (López-Londoño et al., 2021, 2023), in addition to the proximity of the reef to estuarine systems (such as the bay of Cartagena; Restrepo et al., 2006) and mangrove formations. These conditions could make Varadero a reef where a wealth of fish species from different ecosystems converge.

This study represents a baseline of knowledge for further research about changes in species composition in this paradoxical reef. There are some common species that are usually found in coral reefs around Cartagena and were not found in Varadero, but this could be due to insufficient sampling effort. However, the sighting of the Nassau grouper is noteworthy, because the last record of this species in the region was published 40 years ago (Köster, 1979). The sighting of the Atlantic Goliath grouper is also outstanding, as this species is critically endangered, globally, and nationally (Chasqui et al., 2017).

Although the fish richness values are not the highest compared to other reef systems worldwide, the water conditions on which the reef is found are suboptimal for coral reef development and are usually associated with a decrease in fish richness and abundance (McKinley and Johnston, 2010). Therefore, the species observed here could represent the highest concentration of fish species to be found in the bay of Cartagena, an aspect that should be considered before continuing the plans of dredging a canal through the reef.

CONCLUSIONS

The Varadero coral reef supports a fish species richness that corresponds to its amazing structure and state of conservation, despite the poor water conditions under which it survives. This fish community is comparable to other coral areas in the Colombian Caribbean of greater extension and traditionally considered centers of biodiversity. Other groups of organisms in Varadero should reflect an equivalent richness, and the ecosystem should be protected from developments that threaten its survival.