INTRODUCTION

Breast neoplasm is a world clinical problem. In 2016, over 9 million deaths occurred due to cancer, and the most common cancer among females is breast cancer [1,2]. Unlike other types of cancer, breast cancer is usually diagnosed early, and the 5-years related survival rates are 89% [2]. For the next decade, the population with a diagnosis of cancer is projected to increase by 31%, of which there would be a high proportion of patients with breast cancer [3].

Patients with cancer develop unfavorable clinical conditions (physical and psychological), which decrease their quality of life (QoL) and well-being. Some conditions are developed through the very experience of cancer, and others because of treatments such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy [4 - 6].

Common psychological comorbidities in breast cancer patients studies are depression [7-11], cognitive alterations [6,12 - 15], anxiety [16 - 18], distress [19 - 21], fear of cancer [22,23], sleep disorders [24-26], fatigue [27] and reduced QoL [28 - 30]; these clinical conditions may persist in cancer survivors. Therefore, it is important to do research on psychological interventions to treat psychological morbidities in breast cancer.

Psychotherapy is a non-pharmacological intervention to treat psychological morbidities. There are several approaches to psychotherapy, involving a wide range of assistance and intervention. Cognitive therapies, behavioral therapies, cognitive-behavioral therapies, psychodynamic therapies, systemic therapies, and psychosocial therapies are the most widely applied [31]. Medical treatments for cancer and the psychological outcomes resulting from those differ from patient to patient, depending on the stage of cancer they have, which means it is necessary to use psychotherapy to treat mental health problems in each patient [31].

There are three reviews in psychological interventions for women with breast cancer. One of them is a Cochrane Review for women with non-metastatic breast cancer, updated in 2013. It analyzed 3.940 patients through twenty-eight randomized controlled trials (RCTs) [32]. They found that the most common interventions were based on cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT). They also found different psychological outcomes such as depression, anxiety, mood disturbance, unhealthy coping mechanisms, stress, and distress.

On the other hand, there are two systematic reviews of psychological interventions for women with metastatic breast cancer. The first study is a Cochrane Review, including 1,378 patients through ten RCTs [33], and it focuses on psychological interventions' effects on psychosocial and survival outcomes, updated in 2012. The psychological treatment used was CBT and supportive-expressive group therapy (SEGT). Psychosocial and survival outcomes were pain, decreasing in QoL, relationship and social issues, and sleep problems.

The second study, updated in 2016, reported 1,638 patients participated in fifteen RCTs [34]. Psychological interventions reported was SEGT, CBT, expressive writing, hypnosis, and telephone counseling. The psychological outcomes found were distress, unhealthy coping mechanisms, decreasing of QoL, pain, fatigue, and sleep deprivation.

METHOD

This systematic review followed the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [35], for search and evaluation studies, PRISMA Statement [36] for flow diagram (Figure I), and the review protocol was registered as CRD42018088351 in PROSPERO: International prospective register of systematic reviews (Data Supplementary).

Search Strategy

An author systematically searched the published data in EMBASE, ScienceDirect, MEDLINE (Ovid), CENTRAL (Ovid) and PsycINFO (APA PsyNET), from Jan 2014 to Jun 4th, 2018. The key search terms were "Psychological therapy" OR "Psychotherapy" AND "breast cancer" OR "breast neoplasm" AND "randomized controlled trial", and filtered by "Article" in publications type and limited to English publication.

Keywords were based in two vocabularies-controlled thesauruses: MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) by PubMed and Emtree by EMBASE.

Study Selection and Eligibility Criteria

Two authors reviewed all title articles and abstracts in databases and selected potentially eligible studies. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (A) Female patients with breast cancer, any stage. (B) At least one psychotherapy intervention. (C) RCT as research design. On the other hand, the exclusion criteria were: (A) No psychological therapy as the intervention. (B) Breast cancer survivor patients. (C) Patients with another kind of cancer. (D) Do not meet all inclusion criteria.

Most of the articles from eligible studies were extracted from databases, and some were solicited via mail to authors. Grey literature was not included in this review.

Data Extraction

The procedure for this systematic review followed an extraction formulary based on "Data collection form for intervention reviews: RCTs and non-RCTs" of The CHOCRANE Collaboration; two researchers evaluated each full-text article to select the final sample and exclude those that do not meet all inclusion criteria or with non-sufficient quality. Another researcher verified, in an aleatory manner, the procedure and evaluated reports.

Four records were identified through follow-up articles included in qualitative synthesis, which had original articles for extraction and analysis.

Quality Assessment

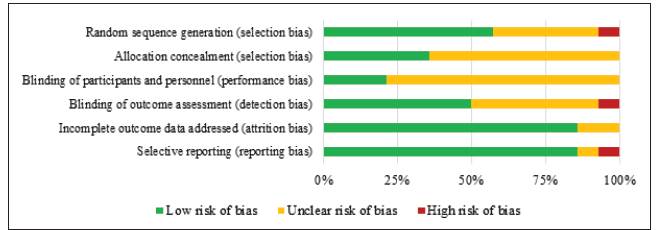

The quality of each study was assessed by two authors, independently. The quality was evaluated using the criteria from the Cochrane Collaboration's "risk of bias" tool [35]. This tool focuses on the following potential risks of bias: Selection bias (sequence generation and allocation concealment); Performance bias (blinding of participants and personnel); Detection bias (blinding of outcomes assessment); Attrition bias (incomplete outcome data addressed), and Reporting bias (selective reporting). There are three categories to report the overall risk per each bias: low risk of bias, unclear risk of bias, and high risk of bias.

The authors combined their independent evaluations to define the risk of bias for each study. A third investigator solved disagreements.

RESULTS

The fourteen randomized controlled trials comprised 1914 participants. Fig. 1, following PRISMA Statement [36], illustrates the search results and the process of screening and selecting studies for inclusion in this review.

By screening 100 records, a total of 21 potentially relevant papers were identified, and their full texts were retrieved. Four studies were excluded because one was a protocol, the other was not an RCT, and two were not psychological interventions. Of the remaining 17 full-text articles, three were follow-up reports, the reason why we added original articles (n=4). Finally, 21 articles were included in this systematic review, equivalent to 14 RCTs.

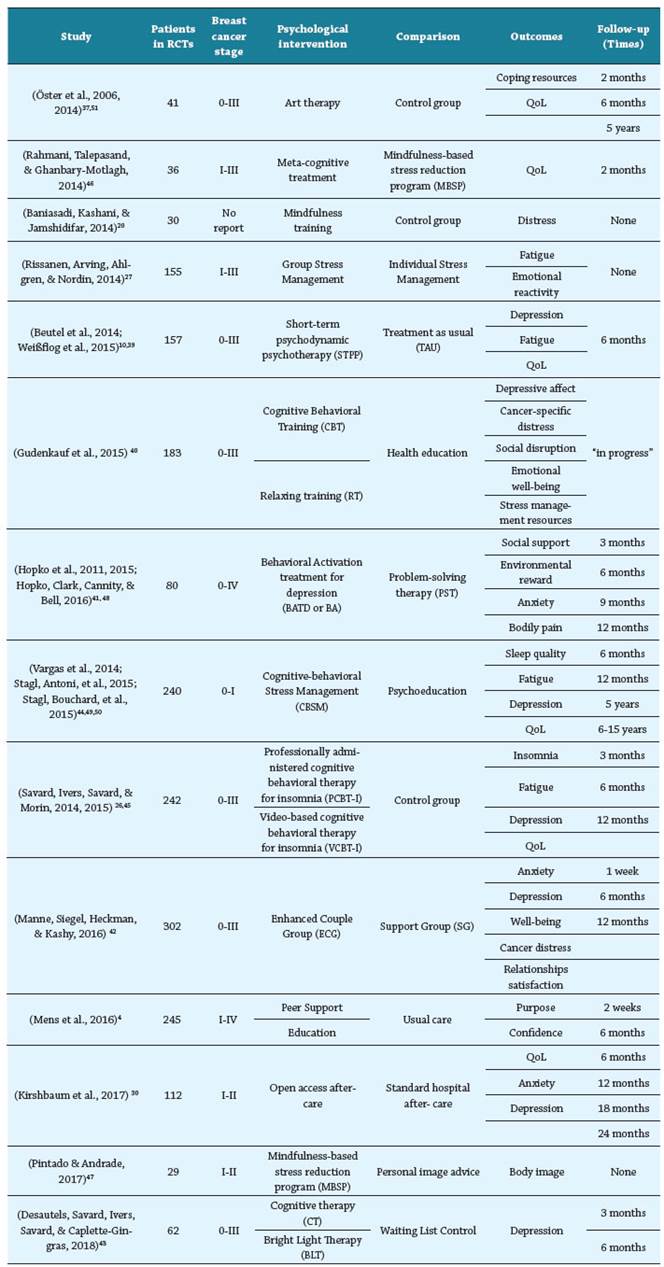

The characteristics of the included studies: number of randomized participants, breast cancer stage, intervention received, assessment outcomes, and time points for assessments, are listed in Table I.

Methodological Quality

Figure II describes the general levels of risk of bias. Even though all studies were RCTs, only eight clearly explained the random generation sequence [25,37 - 43], and just five described adequate concealment of allocations [39,40,44,45]. Allocation concealment and blinding of participants and personnel represent the main limitation and its risk of bias is unclear in most of the studies [4,20,47,30,37 - 40,42,43,46], probably per intervention setting used. Detection bias has a low risk of bias in seven studies, unclear risk in six, and high risk of bias in one study. Finally, twelve studies present a low risk of attrition and reporting bias.

Psychological Interventions

The principal outcome of the present review is the implementation of psychotherapies during breast cancer. All psychological interventions were short-term therapies; the average length was 6 hours, longer interventions lasted 20 hours, and the shortest lasted 1 hour. Only art therapy intervention studies did not report duration in hours. Across 14 RCTs, twenty-two psychological interventions were identified, and it can be categorized into the following:

Cognitive-Behavioral based (13 therapies): it is the most common framework of intervention in breast cancer. The methods and techniques used in these therapies were: behavioral activation; cognitive restructuring and motivation exercises; biofeedback, mindfulness, and meditation; relaxation training; skills training (emotional, social, coping and communication); and education-focused component and group discussion [9,20,47 - 49,26,27,30,40,41,43,45,46]. Doctoral-level students in clinical psychology provided four therapies, other four by Master Clinical Psychologist, two by Nurses, three did not specify, and one was a video-based therapy.

Psychoeducation and health education (4 interventions): it includes different topics to teach, such as: Breast cancer diagnosis, treatments, impacts, and care; healthy lifestyle behaviors (nutrition, sleep, and physical activity); body image and breast reconstruction; quality of life after breast cancer, relationships, and sexuality [4,30,40,49,50]. One intervention was administrated by oncology social workers, the other by nurses, and two studies did not specify.

Group intervention (3 interventions): strategies used in these kinds of intervention were group discussion, share experiences, express emotion, psychoeducation, breathing relaxation, speaker-listener role-taking, progressive muscle relaxation, guided imagery, problem-solving model, and cognitive restructuring [4,27,42]. Therapies were administrated by different professionals, like master's level social workers, master's level psychologists, doctoral-level psychologists, and oncology social workers.

Other interventions: One was art therapy, it focuses on insight, expressing emotion, body examination using sheets of paper, roll paper, oil pastels, watercolors, lead pencils, charcoal, tape, scissors, and paintbrushes, and guided by an art therapist [37,51]. Another intervention was psychodynamic psychotherapy, provided by psychodynamic psychotherapists who used supportive alliance building and interpretative interventions [10,39].

Psychological Outcomes

Psychological interventions in RCTs reviewed, assessed the following outcomes: Depression [9, 26, 49, 50, 30, 39 - 43, 45, 48], Quality of Life [26, 30, 37, 39, 45, 46, 49 - 51], Fatigue [10, 26, 38, 40, 45, 49], Anxiety [9, 30, 41, 42], Distress and Cancer distress [20, 40, 42], Social domain [40 - 42], sleep [45,49], body dimension [41, 47] and others psychological outcomes like coping resources, stress management resources, well-being, emotional well-being, emotional reactivity, and purpose of life [4, 37, 38, 40, 42].

Participants characteristics

Most studies (n=11) included participants with non-metastatic breast cancer; nevertheless, two included women with metastatic and non-metastatic breast cancer. Altogether, there were 1845 women with non-metastatic breast cancer and 69 women with metastatic breast cancer across 14 RCTs. The age of the participants was, on average, 54,8 years. Only one study [20] did not report participant characteristics.

The number of participants in each study is varied, from 29 to 302 women.

Effects of Psychological Interventions

On the one hand, Cognitive-Behavioral based interventions report following effects in patient with breast cancer: Meta-cognitive treatment and MBSP were helped to recognize, accept, and improve the thoughts and emotions related to the body, as well as improving global and specific quality of life. In addition, Mindfulness training results in reduction of distress and defective thinking pattern. Furthermore, CBT and RT may help promote stress management skills and improve psychological adaptation, especially during the early period of adjuvant treatment. Moreover, BATD and problem-solving interventions improve psychological outcomes and quality of life among depressed patients; in the same way, patients who received CBSM reported lower depressive symptoms and better QoL. Likewise, CT supports the efficacy for depressive symptoms, and it is suggested that BLT could be used as an alternative when CT is not accessible. Finally, regarding insomnia in patients with breast cancer, the larger effects were identified in PCBT-I, although VCBT-I produced good effects at posttreatment compared to the control group.

On the other, Education interventions have positive short-term effects on well-being among women with early-stage breast cancer. Most of these interventions were administrated to control or comparison group (see Table I) demonstrating positive results, but less than the effects of comparative interventions.

Regarding group interventions, ECG and SG show that anxiety, depressive symptoms, and cancer-specific distress declined, and positive well-being improved for the couples enrolled41. Likewise, Peer support intervention has positive short-term effects on well-being among women with late and early-stage breast cancer, and changes in life purpose partially mediate these effects. Group Stress Management shows no significant differences in comparison with Individual Stress Management. Despite that fact, literature supports that this intervention reduces risk for PTSD and positively affects QoL.

About the Other interventions, Art therapy reports there were positive effects within six months after the intervention, but there were no long-term effects five to seven years after art therapy intervention compared to a control group [37,51]. With respect to STPP, the study concludes that STPP is an effective treatment of a broad range of depressive conditions in breast cancer patients, improving depression and functional QoL [10,39].

DISCUSSION

Results on the present review are useful to clarify an overview of interventions in psychological morbidities in breast cancer. Comorbidities are varied [52], add more costs to patients [53], and the research on them is insufficient. Cognitive impairment, sexual dysfunctions, patient compliance, end-of-life care, and other conditions are approached with clinical psychology, despite no empiric evidence about psychological interventions, to resolve these psychological morbidities in women with breast cancer.

Results in this study are like those of the Cochrane Review (2015) of psychological interventions for women with non-metastatic breast cancer, where psychological interventions were: CBT, Psychotherapy (include psychodynamic intervention) and informational (psychoeducation, health education) counseling. Likewise, two predecessor reviews (2013, 2016) in search of psychological interventions in women with metastatic breast cancer, found CBT, group therapies, and "low intensity" therapies (include telephone counseling and expressive writing).

On the other hand, the psychological outcomes of this research coincide with systematic reviews that mentioned that most studies addressed depression, followed by QoL, fatigue, anxiety, stress, and distress. In addition, others psychological outcomes evaluated were a social domain (Relationships satisfaction, social support, and social disruption), quality of sleep and insomnia, body pain and body image, coping resources, stress management resources, well-being, emotional well-being, emotional reactivity, and purpose. Notwithstanding, there was no assessment of mood disturbance in none of the studies.

The importance of providers in psychological interventions should be noted. It is necessary to intervene in psychological variables; responsible professionals have extensive training and expertise in the clinical area. The interventions were delivered principally by Master Clinical Psychologist and doctoral-level students in clinical psychology. Other providers were nurses, social workers, and one of the interventions was video based. Nevertheless, four studies did not specify who delivered the implemented therapies.

Regarding methodological quality, the reviewed RCTs had, as the principal risk of bias, blinding participants and personnel. This is limiting because of the setting of the psychological intervention, its delivery, and follow-up. Regarding detection bias, some studies did not blind outcomes assessment, which may have interfered in recollection and analysis of psychological outcomes. Hence, it is recommended to future researchers to be thorough in methodological setting to reduce risks of bias. Most recent research agrees on the absence of evidence to recommend therapies for this population and highlighted the need for multidisciplinary collaboration [54,55].

This review identifies women with breast cancer, psychological interventions, psychological outcomes and contributes to understanding this problem trough evidence-based knowledge for clinical decisions. In conclusion, it is fundamental for patients with breast cancer to receive psychological intervention to solve psychological morbidities and improve QoL. Finally, it is necessary to develop an investigation to reduce the lack of data in this field.

Clinical Implications

The current review provides therapists with an overview of the psychological approach to co-morbidities in breast cancer patients. In addition, it also provides a panoramic of psychological therapies based on evidence, to facilitate clinical decisions.

Depression is the most investigated co-morbidity in breast cancer, for which the following psychotherapies were identified: Open access aftercare, Enhanced Couple Group (ECG), Support Group, Psychoeducation, Cognitive-behavioral Stress Management (CBSM), Cognitive Behavioral Training (CBT), Relaxing training (RT), Short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy (STPP), Problem-solving therapy (PST), and Behavioral Activation treatment for depression (BATD or BA).

Meanwhile, to improve QoL, the following interventions were applied: Art therapy, Meta-cognitive treatment, Mindfulness-based stress reduction program (MBSP), Short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy (STPP), Cognitive-behavioral Stress Management (CBSM), psychoeducation, professionally administered cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia, Video-based cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia, and Open access after-care.

The psychotherapies for breast cancer patients with fatigue were: Group Stress Management, Individual Stress Management, Short-term Psychodynamic Psychotherapy (STPP), Cognitive-behavioral Stress Management (CBSM), and Psychoeducation.

Regarding patients with Anxiety or Distress/Cancer-specific distress, the interventions used: Problem-solving therapy (PST), Behavioral Activation treatment for depression (BATD or BA), Enhanced Couple Group (ECG), Support Group, Open access after-care, Mindfulness training, Health Education, Cognitive Behavioral Training (CBT), and Relaxing training (RT). Other psychological morbidities and its treatments can be identified in Table 1.

Finally, the current review only makes relatively tentative recommendations about the psychological interventions in enhancing breast cancer patient outcomes, considering the methodological limits in the present study.